Thomas McKean: Difference between revisions

Filling in 5 references using Reflinks |

Rescuing 4 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.5beta) |

||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

The governor's beliefs in strong executive and judicial powers were bitterly denounced by the influential ''Aurora'' newspaper publisher, [[William P. Duane]], and the Philadelphia populist, Dr. Michael Leib. After they led public attacks calling for his impeachment, McKean filed a partially successful libel suit against Duane in 1805. The Pennsylvania House of Representatives impeached the governor in 1807, but his friends prevented a trial for the rest of his term, and the matter was dropped. |

The governor's beliefs in strong executive and judicial powers were bitterly denounced by the influential ''Aurora'' newspaper publisher, [[William P. Duane]], and the Philadelphia populist, Dr. Michael Leib. After they led public attacks calling for his impeachment, McKean filed a partially successful libel suit against Duane in 1805. The Pennsylvania House of Representatives impeached the governor in 1807, but his friends prevented a trial for the rest of his term, and the matter was dropped. |

||

When the suit was settled after McKean left office, his son Joseph angrily criticized Duane's attorney for alleging, out of context, that McKean referred to the people of Pennsylvania as "Clodpoles" (clodhoppers).<ref>[http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/governors/mckean.asp?secid=31 Pennsylvania Governors]{{ |

When the suit was settled after McKean left office, his son Joseph angrily criticized Duane's attorney for alleging, out of context, that McKean referred to the people of Pennsylvania as "Clodpoles" (clodhoppers).<ref>[http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/governors/mckean.asp?secid=31 Pennsylvania Governors] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050923045842/http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/governors/mckean.asp?secid=31 |date=September 23, 2005 }}</ref> |

||

[[File:ThomasMcKean2.jpg|225px|Thomas McKean |right]] |

[[File:ThomasMcKean2.jpg|225px|Thomas McKean |right]] |

||

| Line 136: | Line 136: | ||

Oddly, the name of "Keap Street" in [[Brooklyn]], New York is the result of an erroneous effort to name a street after him. Many Brooklyn streets are named after signers of the Declaration of Independence, and "Keap Street" is the result of planners being unable to accurately read his signature.<ref>Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss, Brooklyn By Name; New York University Press, 2006</ref> In some accounts the "M" of McKean was mistaken for a middle initial, and the flourish on the "n" in McKean led to the n being misread as a "p." |

Oddly, the name of "Keap Street" in [[Brooklyn]], New York is the result of an erroneous effort to name a street after him. Many Brooklyn streets are named after signers of the Declaration of Independence, and "Keap Street" is the result of planners being unable to accurately read his signature.<ref>Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss, Brooklyn By Name; New York University Press, 2006</ref> In some accounts the "M" of McKean was mistaken for a middle initial, and the flourish on the "n" in McKean led to the n being misread as a "p." |

||

McKean was over six feet tall, always wore a large cocked hat and carried a gold-headed cane. He was a man of quick temper and vigorous personality, "with a thin face, hawk's nose and hot eyes." John Adams described him as "one of the three men in the Continental Congress who appeared to me to see more clearly to the end of the business than any others in the body." As Chief Justice and Governor of Pennsylvania he was frequently the center of controversy.<ref>http://www.si.edu/harcourt/npg/col/age/mckean2.htm</ref><ref>[http://www2.cybergolf.com/sites/courses/talamore.asp?id=300&page=7779 Pine Run Farms – The McKean Estate]{{ |

McKean was over six feet tall, always wore a large cocked hat and carried a gold-headed cane. He was a man of quick temper and vigorous personality, "with a thin face, hawk's nose and hot eyes." John Adams described him as "one of the three men in the Continental Congress who appeared to me to see more clearly to the end of the business than any others in the body." As Chief Justice and Governor of Pennsylvania he was frequently the center of controversy.<ref>http://www.si.edu/harcourt/npg/col/age/mckean2.htm</ref><ref>[http://www2.cybergolf.com/sites/courses/talamore.asp?id=300&page=7779 Pine Run Farms – The McKean Estate] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927022336/http://www2.cybergolf.com/sites/courses/talamore.asp?id=300&page=7779 |date=September 27, 2007 }}</ref> |

||

==In popular culture== |

==In popular culture== |

||

| Line 570: | Line 570: | ||

* [http://www.russpickett.com/history/delgov1.htm#mckean Delaware’s Governors] |

* [http://www.russpickett.com/history/delgov1.htm#mckean Delaware’s Governors] |

||

* [http://politicalgraveyard.com/bio/mckeague-mckechnie.html#RAZ0UEQKM The Political Graveyard] |

* [http://politicalgraveyard.com/bio/mckeague-mckechnie.html#RAZ0UEQKM The Political Graveyard] |

||

* [http://users.clover.net/mckean/ Biography by Keith J. McLean] |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20051025030421/http://users.clover.net/mckean/ Biography by Keith J. McLean] |

||

* [http://www.hsd.org/DHE/DHE_who_McKean.htm Historical Society of Delaware] |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20060716180827/http://www.hsd.org/DHE/DHE_who_McKean.htm Historical Society of Delaware] |

||

* [http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/declaration/bio30.htm National Park Service] |

* [http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/declaration/bio30.htm National Park Service] |

||

* [http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/governors/mckean.asp?secid=31 Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission] |

* [http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/governors/mckean.asp?secid=31 Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission] |

||

Revision as of 19:44, 26 July 2017

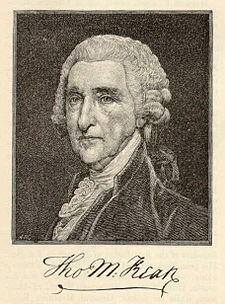

Thomas McKean | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Charles Willson Peale | |

| 2nd Governor of Pennsylvania | |

| In office December 17, 1799 – December 20, 1808 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Mifflin |

| Succeeded by | Simon Snyder |

| Chief Justice of Pennsylvania | |

| In office July 28, 1777 – December 17, 1799 | |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Chew |

| Succeeded by | Edward Shippen |

| 8th President of the Continental Congress | |

| In office July 10, 1781 – November 4, 1781 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel Huntington |

| Succeeded by | John Hanson |

| Continental Congressman from Delaware | |

| In office December 17, 1777 – February 1, 1783 | |

| In office August 2, 1774 – November 7, 1776 | |

| President of Delaware | |

| In office September 22, 1777 – October 20, 1777 | |

| Preceded by | John McKinly |

| Succeeded by | George Read |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 19, 1734 New London Township, Province of Pennsylvania, British America |

| Died | June 24, 1817 (aged 83) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia |

| Political party | Federalist Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Borden Sarah Armitage |

| Residence(s) | New Castle, Delaware Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Profession | lawyer |

| Signature |  |

Thomas McKean (March 19, 1734 – June 24, 1817) was an American lawyer and politician from New Castle, in New Castle County, Delaware and Philadelphia. During the American Revolution he was a delegate to the Continental Congress where he signed the United States Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. McKean served as a President of Congress. He was at various times a member of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties. McKean served as President of Delaware, Chief Justice of Pennsylvania, and Governor of Pennsylvania.

Early life and family

McKean was born in New London Township in the Province of Pennsylvania. He was the son of William McKean and Letitia Finney. His father was a tavern-keeper in New London and both his parents were Irish-born Ulster-Scots who came to Pennsylvania as children from Ballymoney, County Antrim, Ireland. Mary Borden was his first wife. They married in 1763, and lived at 22 The Strand in New Castle, Delaware. They had six children: Joseph, Robert, Elizabeth, Letitia, Mary, and Anne. Mary Borden McKean died in 1773 and is buried at Immanuel Episcopal Church in New Castle. Sarah Armitage was McKean's second wife. They married in 1774, lived at the northeast corner of 3rd and Pine Streets in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and had four children, Sarah, Thomas, Sophia, and Maria. They were members of the New Castle Presbyterian Church in New Castle and the First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia. McKean's daughter Sarah married Spanish diplomat Carlos Martínez de Irujo, 1st Marquis of Casa Irujo; their son, Carlos Martínez de Irujo y McKean, would later become Prime Minister of Spain.

Colonial career

McKean's education began at the Reverend Francis Allison's New London Academy. At the age of sixteen he went to New Castle, Delaware to begin the study of law under his cousin, David Finney. In 1755 he was admitted to the Bar of the Lower Counties, as Delaware was then known, and likewise in the Province of Pennsylvania the following year. In 1756 he was appointed deputy Attorney General for Sussex County. From the 1762/63 session through the 1775/76 session he was a member of the General Assembly of the Lower Counties, serving as its Speaker in 1772/73. From July 1765, he also served as a judge of the Court of Common Pleas and began service as the customs collector at New Castle in 1771. In November 1765 his Court of Common Pleas became the first such court in the colonies to establish a rule that all the proceedings of the court be recorded on un-stamped paper.

Eighteenth century Delaware was politically divided into loose political factions known as the "Court Party" and the "Country Party." The majority Court Party was generally Anglican, strongest in Kent and Sussex counties and worked well with the colonial Proprietary government, and was in favor of reconciliation with the British government. The minority Country Party was largely Ulster-Scot, centered in New Castle County, and quickly advocated independence from the British. McKean was the epitome of the Country party politician and was, as much as anyone, its leader. As such, he generally worked in partnership with Caesar Rodney from Kent County, and in opposition to his friend and neighbor, George Read.

At the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, McKean and Caesar Rodney represented Delaware. McKean proposed the voting procedure that the Continental Congress later adopted: that each colony, regardless of size or population, have one vote. This decision set the precedent, the Congress of the Articles of Confederation adopted the practice, and the principle of state equality continued in the composition of the United States Senate.

McKean quickly became one of the most influential members of the Stamp Act Congress. He was on the committee that drew the memorial to Parliament, and with John Rutledge and Philip Livingston, revised its proceedings. On the last day of its session, when the business session ended, Timothy Ruggles, the president of the body, and a few other more cautious members, refused to sign the memorial of rights and grievances. McKean arose and addressing the chair insisted that the president give his reasons for his refusal. After refusing at first, Ruggles remarked, "it was against his conscience." McKean then disputed his use of the word "conscience" so loudly and so long that a challenge was given by Ruggles and accepted in the presence of the congress. However, Ruggles left the next morning at daybreak, so that the duel did not take place.[1]

American Revolution

In spite of his primary residence in Philadelphia, McKean remained the effective leader for American independence in Delaware. Along with George Read and Caesar Rodney, he was one of Delaware's delegates to the First Continental Congress in 1774 and the Second Continental Congress in 1775 and 1776.

Being an outspoken advocate of independence, McKean's was a key voice in persuading others to vote for a split with Great Britain. When Congress began debating a resolution of independence in June 1776, Caesar Rodney was absent. George Read was against independence, which meant that the Delaware delegation was split between McKean and Read and therefore could not vote in favor of independence. McKean requested that the absent Rodney ride all night from Dover to break the tie. After the vote in favor of independence on July 2, McKean participated in the debate over the wording of the official Declaration of Independence, which was approved on July 4.

A few days after McKean cast his vote, he left Congress to serve as colonel in command of the Fourth Battalion of the Pennsylvania Associators, a militia unit created by Benjamin Franklin in 1747. They joined Washington's defense of New York City at Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Being away, he was not available when most of the signers placed their signatures on the Declaration of Independence on August 2, 1776. Since his signature did not appear on the printed copy that was authenticated on January 17, 1777, it is assumed that he signed after that date, possibly as late as 1781.[3]

In a conservative reaction against the advocates of American independence, the 1776/77 Delaware General Assembly did not reelect either McKean or Caesar Rodney to the Continental Congress in October 1776. However, the British occupation following the Battle of Brandywine swung opinions enough that McKean was returned to Congress in October 1777 by the 1777/78 Delaware General Assembly. He then served continuously until February 1, 1783. McKean helped draft the Articles of Confederation and voted for their adoption on March 1, 1781.

When poor health caused Samuel Huntington, to resign as President of Congress in July 1781, McKean was elected as his successor. He served from July 10, 1781, until November 4, 1781. The President of Congress was a mostly ceremonial position with no real authority, but the office did require McKean to handle a good deal of correspondence and sign official documents.[4] During his time in office, Lord Cornwallis's British army surrendered at Yorktown, effectively ending the war.

Government of Delaware

Meanwhile, McKean led the effort in the General Assembly of Delaware to declare its separation from the British government, which it did on June 15, 1776. Then, in August, he was elected to the special convention to draft a new state constitution. Upon hearing of it, McKean made the long ride to Dover, Delaware from Philadelphia in a single day, went to a room in an Inn, and that night, virtually by himself, drafted the document. It was adopted September 20, 1776. The Delaware Constitution of 1776 became the first state constitution to be produced after the Declaration of Independence.

McKean was then elected to Delaware's first House of Assembly for both the 1776/77 and 1778/79 sessions, succeeding John McKinly as Speaker on February 12, 1777 when McKinly became President of Delaware. Shortly after President McKinly's capture and imprisonment, McKean served as the President of Delaware for a month, from September 22, 1777 to October 20, 1777. That was the time needed for the rightful successor to John McKinly, the Speaker of the Legislative Council, George Read, to return from the Continental Congress in Philadelphia and assume the duties.

At this time, immediately after the Battle of Brandywine, the British Army occupied Wilmington and much of northern New Castle County. Its navy also controlled the lower Delaware River and Delaware Bay. As a result, the state capital, New Castle, was unsafe as a meeting place, and the Sussex County seat, Lewes, was sufficiently disrupted by Loyalists that it was unable to hold a valid general election that autumn. As President, McKean was primarily occupied with recruitment of the militia and with keeping some semblance of civic order in the portions of the state still under his control.

| Delaware General Assembly (sessions while President) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Assembly | Senate Majority | Speaker | House Majority | Speaker | ||||||

| 1776/77 | 1st | non-partisan | George Read | non-partisan | vacant | ||||||

Government of Pennsylvania

McKean started his long tenure as Chief Justice of Pennsylvania on July 28, 1777 and served in that capacity until 1799. There he largely set the rules of justice for revolutionary Pennsylvania. According to biographer John Coleman, "only the historiographical difficulty of reviewing court records and other scattered documents prevents recognition that McKean, rather than John Marshall, did more than anyone else to establish an independent judiciary in the United States. As chief justice under a Pennsylvania constitution he considered flawed, he assumed it the right of the court to strike down legislative acts it deemed unconstitutional, preceding by ten years the U.S. Supreme Court's establishment of the doctrine of judicial review. He augmented the rights of defendants and sought penal reform, but on the other hand was slow to recognize expansion of the legal rights of women and the processes in the state's gradual elimination of slavery."

He was a member of the convention of Pennsylvania, which ratified the Constitution of the United States. In the Pennsylvania State Constitutional Convention of 1789/90, he argued for a strong executive and was himself a Federalist. Nevertheless, in 1796, dissatisfied with Federalist domestic policies and compromises with Great Britain, he became an outspoken Jeffersonian Republican or Democratic-Republican.

While Chief Justice of Pennsylvania, McKean played a role in the Whiskey Rebellion. On August 2, 1794, he took part in a conference on the rebellion. In attendance was Washington, his Cabinet, the Governor of Pennsylvania, and other officials. President Washington interpreted the rebellion to be a grave threat could mean "an end to our Constitution and laws." Washington advocated "the most spirited and firm measure" but held back on what that meant. McKean argued that the matter should be left up to the courts, not the military, to prosecute and punish the rebels. Alexander Hamilton naturally, insisted upon the "propriety of an immediate resort to Military force."[5]

Some weeks later, Mckean and General William Irvine wrote Pennsylvania Governor, Thomas Mifflin, and discussed the mission of federal committees to negotiate with the Rebels, describing them as "well disposed." However, McKean and Irvine felt the government must suppress the insurrection to prevent it from spreading to nearby counties.[6]

McKean was elected Governor of Pennsylvania and served three terms from December 17, 1799 until December 20, 1808. In 1799 he defeated the Federalist Party nominee, James Ross, and again more easily in 1802. At first, McKean ousted Federalists from state government positions and so he has been called the father of the spoils system. However, in seeking a third term in 1805, McKean was at odds with factions of his own Democratic-Republican Party, and the Pennsylvania General Assembly instead nominated Speaker Simon Snyder for Governor. McKean then forged an alliance with Federalists, called "the Quids," and defeated Snyder. Afterwards, he began removing Jeffersonians from state positions.

The governor's beliefs in strong executive and judicial powers were bitterly denounced by the influential Aurora newspaper publisher, William P. Duane, and the Philadelphia populist, Dr. Michael Leib. After they led public attacks calling for his impeachment, McKean filed a partially successful libel suit against Duane in 1805. The Pennsylvania House of Representatives impeached the governor in 1807, but his friends prevented a trial for the rest of his term, and the matter was dropped.

When the suit was settled after McKean left office, his son Joseph angrily criticized Duane's attorney for alleging, out of context, that McKean referred to the people of Pennsylvania as "Clodpoles" (clodhoppers).[7]

Some of McKean's other accomplishments included expanding free education for all and, at age eighty, leading a Philadelphia citizens group to organize a strong defense during the War of 1812. He spent his retirement in Philadelphia, writing, discussing political affairs and enjoying the considerable wealth he had earned through investments and real estate.

Death and legacy

McKean was a member of the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati in 1785 and was subsequently its vice-president. Princeton College gave him the degree of L.L.D. in 1781, Dartmouth College presented the same honor in 1782, and the University of Pennsylvania gave him the degree of A.M. in 1763 and L.L.D. in 1785. With Professor John Wilson he published "Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States" in 1790.

McKean died in Philadelphia and was buried in the First Presbyterian Church Cemetery there. In 1843, his body was moved to the Laurel Hill Cemetery, also in Philadelphia.[8] McKean County, Pennsylvania[9] is named in his honor, as is Thomas McKean High School in New Castle County, also McKean Street in Philadelphia, and the McKean Hall dormitory at the University of Delaware. Penn State University also has a residence hall and a campus road named for him.

Oddly, the name of "Keap Street" in Brooklyn, New York is the result of an erroneous effort to name a street after him. Many Brooklyn streets are named after signers of the Declaration of Independence, and "Keap Street" is the result of planners being unable to accurately read his signature.[10] In some accounts the "M" of McKean was mistaken for a middle initial, and the flourish on the "n" in McKean led to the n being misread as a "p."

McKean was over six feet tall, always wore a large cocked hat and carried a gold-headed cane. He was a man of quick temper and vigorous personality, "with a thin face, hawk's nose and hot eyes." John Adams described him as "one of the three men in the Continental Congress who appeared to me to see more clearly to the end of the business than any others in the body." As Chief Justice and Governor of Pennsylvania he was frequently the center of controversy.[11][12]

In popular culture

In the Broadway musical, 1776, McKean is portrayed as a gun-toting, cantankerous old Scot who cannot get along with the wealthy and conservative planter George Read.[citation needed] This is actually close to the truth (minus the gun toting) as McKean and Read belonged to opposing political factions in Delaware.[citation needed] McKean was portrayed by Bruce MacKay[13] in the original Broadway cast and Ray Middleton[14] in the film version.

Almanac

Delaware elections were held October 1 and members of the General Assembly took office on October 20 or the following weekday. State Assemblymen had a one-year term. The whole General Assembly chose the Continental Congressmen for a one-year term and the State President for a three-year term. Judges of the Courts of Common Pleas were also selected by the General Assembly for the life of the person appointed. McKean served as State President only temporarily, filling the vacancy created by John McKinly's capture and resignation and awaiting the arrival of George Read.

Pennsylvania elections were held in October as well. The Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council was created in 1776 and counsellors were popularly elected for three-year terms. A joint ballot of the Pennsylvania General Assembly and the Council chose the President from among the twelve Counsellors for a one-year term. The Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court was also selected by the General Assembly and Council for the life of the person appointed.

| Delaware General Assembly service | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | Assembly | Chamber | Majority | Governor | Committees | District |

| 1776/77 | 1st | State House | non-partisan | John McKinly | Speaker | New Castle at-large |

| 1778/79 | 3rd | State House | non-partisan | Caesar Rodney | New Castle at-large | |

| Election results | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Office | State | Subject | Party | Votes | % | Opponent | Party | Votes | % | ||

| 1799 | Governor | Pennsylvania | Thomas McKean | Republican | 38,036 | 54% | James Ross | Federalist | 32,641 | 46% | ||

| 1802 | Governor | Pennsylvania | Thomas McKean | Republican | 47,879 | 83% | James Ross | Federalist | 9,499 | 17% | ||

| 1805 | Governor | Pennsylvania | Thomas McKean | Independent | 43,644 | 53% | Simon Snyder | Republican | 38,438 | 47% | ||

Notes

- ^ "Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence". Colonialhall.com. September 27, 2005. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ "Key to Declaration". Americanrevolution.org. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ G. S. Rowe, "McKean, Thomas". American National Biography Online, February 2000.

- ^ Rick K. Wilson, Congressional Dynamics: ...in the First American Congress, 1774–1789 (Stanford University Press, 1994), 76–80.

- ^ Center for History and New Media, George Mason University. "Insurrection in Western Pennsylvania: The Whiskey Rebellion". Papers of the War Department.

- ^ University of Pittsburgh Darlington Autograph Files. "Thomas McKean and William Irvine to Governor Thomas Mifflin, August 22, 1794".

- ^ Pennsylvania Governors Archived September 23, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thomas McKean at Find a Grave

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 194.

- ^ Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss, Brooklyn By Name; New York University Press, 2006

- ^ http://www.si.edu/harcourt/npg/col/age/mckean2.htm

- ^ Pine Run Farms – The McKean Estate Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "1776". IBDB. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "1776". IMDb. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Members of the Delaware Assembly acted unofficially in selecting these delegates as the assembly was not in session.

- ^ He was elected Speaker on February 12, 1777 when John McKinly became State President

- ^ Speaker of the State Assembly, was third in line of succession, upon the capture of John McKinly, and in the absence of George Read.

- ^ He was elected President on July 10. 1781 and served until November 4, 1781

References

- Benardo, Leonard; Jennifer Weiss (2006). Brooklyn By Name. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-9946-9.

- Coleman, John M. (1984). Thomas McKean, Forgotten Leader of the Revolution. Rockaway, New Jersey: American Faculty Press. ISBN 0-912834-07-2.

- Conrad, Henry C. (1908). History of the State of Delaware, 3 vols. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Wickersham Company.

- Hoffecker, Carol E. (2004). Democracy in Delaware. Wilmington, Delaware: Cedar Tree Books. ISBN 1-892142-23-6.

- Martin, Roger A. (1984). A History of Delaware Through its Governors. Wilmington, Delaware: McClafferty Press.

- Martin, Roger A. (1995). Memoirs of the Senate. Newark, Delaware: Roger A. Martin.

- Munroe, John A. (2004). The Philadelawareans. Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-87413-872-8.

- Munroe, John A. (1954). Federalist Delaware 1775–1815. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University.

- Munroe, John A. (1993). History of Delaware. Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-87413-493-5.

- Racino, John W. (1980). Biographical Directory of American and Revolutionary Governors 1607–1789. Westport, CT: Meckler Books. ISBN 0-930466-00-4.

- Rodney, Richard S. (1975). Collected Essays on Early Delaware. Wilmington, Delaware: Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Delaware.

- Rowe, G.S. (1984). Thomas McKean, The Shaping of an American Republicanism. Boulder, Colorado: Colorado University Press. ISBN 0-87081-100-2.

- Scharf, John Thomas (1888). History of Delaware 1609–1888. 2 vols. Philadelphia: L. J. Richards & Co.

- Swetnam, G. (1941). The Governors of Pennsylvania, 1790–1990. McDonald/Sward. ISBN 0-945437-04-8.

- Ward, Christopher L. (1941). Delaware Continentals, 1776–1783. Wilmington, Delaware: Historical Society of Delaware. ISBN 0-924117-21-4.

- Wilson, James Grant.; John Fiske (1888). Appletons Encyclopedia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Images

- Carpenter's Hall; Courtesy of Independence National Historical Park.

- Hall of Governors Portrait Gallery; Portrait courtesy of Historical and Cultural Affairs, Dover.

External links

- Biographical Directory of the Governors of the United States

- Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Biography by Russell Pickett

- Delaware’s Governors

- The Political Graveyard

- Biography by Keith J. McLean

- Historical Society of Delaware

- National Park Service

- Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission

- The Thomas McKean Papers, including correspondence related to the American Revolution, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

External links

- 1734 births

- 1817 deaths

- People from Chester County, Pennsylvania

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- American Presbyterians

- People from Wilmington, Delaware

- Politicians from Philadelphia

- People of Delaware in the American Revolution

- Pennsylvania militiamen in the American Revolution

- Delaware lawyers

- Pennsylvania lawyers

- Pennsylvania Federalists

- Members of the Delaware House of Representatives

- Governors of Delaware

- Governors of Pennsylvania

- Continental Congressmen from Delaware

- 18th-century American politicians

- Supreme Court of Pennsylvania

- Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence

- Signers of the Articles of Confederation

- Pennsylvania Democratic-Republicans

- Members of the Middle Temple

- Democratic-Republican Party state governors of the United States

- Burials at Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia)

- People from New Castle, Delaware