Shipping container architecture: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→Other uses: drunk tanks |

||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

* [[Hydroponics]] farms |

* [[Hydroponics]] farms |

||

* Battery storage units |

* Battery storage units |

||

* [[Drunk tank]]s<ref>{{cite news |last=Aaltonen |first=Riikka |date=2017-07-14 |title=Tältä näyttää Suomen ensimmäinen siirrettävä moduulivankila – Oulun poliisilaitoksen väistötilat saivat käyttöönottoluvan torstaina|url=https://www.kaleva.fi/uutiset/oulu/talta-nayttaa-suomen-ensimmainen-siirrettava-moduulivankila-oulun-poliisilaitoksen-vaistotilat-saivat-kayttoonottoluvan-torstaina/765347/ |work=Kaleva |location=Oulu, Finland |language=fi |access-date=2018-09-27 }}</ref> |

|||

==For housing and other architecture== |

==For housing and other architecture== |

||

Revision as of 16:49, 27 September 2018

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

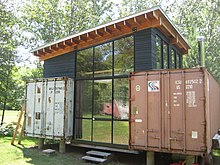

Shipping container architecture is a form of architecture using steel intermodal containers (shipping containers) as structural element. It is also referred to as cargotecture, a portmanteau of cargo with architecture, or "arkitainer".

The use of containers as a building material has grown in popularity over the past several years due to their inherent strength, wide availability, and relatively low expense. Homes have also been built with containers because they are seen[who?] as more eco-friendly than traditional building materials such as brick and cement.[citation needed]

Advantages

- Customized

- Due to their shape and material, shipping containers can be easily modified to fit many purposes.

- Strength and durability

- Shipping containers are designed to be stacked in high columns, carrying heavy loads. They are also designed to resist harsh environments, such as on ocean-going vessels or sprayed with road salt while transported on roads. Due to their high strength, shipping containers are usually the last to fall in extreme weather, such as tornadoes, hurricanes, and tsunamis.

- Modular

- All shipping containers are the same width and most have two standard height and length measurements and as such they provide modular elements that can be combined into larger structures. This simplifies design, planning and transport. As they are already designed to interlock for ease of mobility during transportation, structural construction is completed by simply emplacing them. Due to the containers' modular design, additional construction is as easy as stacking more containers. They can be stacked up to 12 units high when empty.

- Labor

- The welding and cutting of steel is considered to be specialized labor and can increase construction expenses, yet overall it is still lower than conventional construction. Unlike wood frame construction, attachments must be welded or drilled to the outer skin, which is more time consuming and requires different job site equipment.

- Transport

- Because they already conform to standard shipping sizes, pre-fabricated modules can be easily transported by ship, truck, or rail.

- Availability

- Because of their wide-spread use, new and used shipping containers are available across the planet.

- Expense

- Many used containers are available at an amount that is low compared to a finished structure built by other labor-intensive means such as bricks and mortar — which also require larger more expensive foundations.[citation needed]

- Eco-friendly

- A 40 ft shipping container weights over 3,500 kg. When upcycling shipping containers, thousands of kilograms of steel are saved. In addition when building with containers, the amount of traditional building materials needed (i.e. bricks and cement) are reduced.

Disadvantages

- Temperature

- Steel conducts heat very well; containers used for human occupancy in an environment with extreme temperature variations will normally have to be better insulated than most brick, block or wood structures.

- Lack of flexibility

- Although shipping containers can be combined together to create bigger spaces, creating spaces different to their default size (either 20 or 40 foot) is expensive and time consuming. Containers any longer than 40 feet will be difficult to navigate in some residential areas.

- Humidity

- As noted above, single wall steel conducts heat. In temperate climates, moist interior air condenses against the steel, becoming clammy. Rust will form unless the steel is well sealed and insulated.

- Construction site

- The size and weight of the containers will, in most cases, require them to be placed by a crane or forklift. Traditional brick, block and lumber construction materials can often be moved by hand, even to upper stories.

- Building permits

- The use of steel for construction, while prevalent in industrial construction, is not widely used for residential structures. Obtaining building permits may be troublesome in some regions due to municipalities not having seen this application before. However, in the US certain shipping container homes have been built in outside of the city's zoning code; this meant no building permits were required.

- Treatment of timber floors

- To meet Australian government quarantine requirements most container floors when manufactured are treated with insecticides containing copper (23–25%), chromium (38–45%) and arsenic (30–37%). Before human habitation, floors should be removed and safely disposed. Units with steel floors would be preferable, if available.

- Cargo spillages

- A container can carry a wide variety of cargo during its working life. Spillages or contamination may have occurred on the inside surfaces and will have to be cleaned before habitation. Ideally all internal surfaces should be abrasive blasted to bare metal, and re-painted with a nontoxic paint system.

- Solvents

- Solvents released from paint and sealants used in manufacture might be harmful.

- Damage

- While in service, containers are damaged by friction, handling collisions, and force of heavy loads overhead during ship transits. The companies will inspect containers and condemn them if there are cracked welds, twisted frames or pin holes are found, among other faults.

- Roof weaknesses

- Although the two ends of a container are extremely strong, the roof is not. A limit of 300 kg is recommended.[1]

Examples

Many structures based on shipping containers have already been constructed, and their uses, sizes, locations and appearances vary widely.

When futurist Stewart Brand needed a place to assemble all the material he needed to write How Buildings Learn, he converted a shipping container into office space, and wrote up the conversion process in the same book.

In 2006, Southern California Architect Peter DeMaria, designed the first two-story shipping container home in the U.S. as an approved structural system under the strict guidelines of the nationally recognized Uniform Building Code (UBC). This home was the Redondo Beach House and it inspired the creation of Logical Homes, a cargo container based pre-fabricated home company. In 2007, Logical Homes created their flagship project - the Aegean, for the Computer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Several architects, such as Adam Kalkin have built original homes, using discarded shipping containers for their parts or using them in their original form, or doing a mix of both.[2]

In 2000, the firm Urban Space Management completed the project called Container City I in the Trinity Buoy Wharf area of London. The firm has gone on to complete additional container-based building projects, with more underway. In 2006, the Dutch company Tempohousing finished in Amsterdam the biggest container village in the world: 1,000 student homes from modified shipping containers from China.[3]

In 2002 standard ISO shipping containers began to be modified and used as stand-alone on-site wastewater treatment plants. The use of containers creates a cost-effective, modular, and customizable solution to on-site waste water treatment and eliminates the need for construction of a separate building to house the treatment system.

Brian McCarthy, an MBA student, saw many poor neighborhoods in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico during an MBA field trip in the 2000s. Since then he developed prototypes of shipping container housing for typical maquiladora workers in Mexico.[4]

Application for the Live Event & Entertainment Industry: in 2010 German Architect and Production Designer, Stefan Beese, utilized six 40’ long shipping containers to create a large viewing deck and a VIP lounge area for to substitute the typical grand stand scaffold structure at the Voodoo Music Experience, New Orleans. The containers also smartly do double duty as storage space for other festival components throughout the year. The two top containers are cantilevered nine feet on each side creating two balconies that are prime viewing locations. There are also two bars located on the balconies. Each container was perforated with cutouts spelling the word "VOODOO," which not only brands the structure but creates different vantage points and service area openings. And since the openings themselves act as signage for the event, no additional materials or energy were needed to create banners or posters.

In the United Kingdom, walls of containers filled with sand have been used as giant sandbags to protect against the risk of flying debris from exploding ceramic insulators in electricity substations.

In the October 2013, two barges owned by Google with superstructures made out of shipping containers received media attention speculating about their purpose.[5]

Markets

Empty shipping containers are commonly used as market stalls and warehouses in the countries of the former USSR.

The biggest shopping mall or organized market in Europe is made up of alleys formed by stacked containers, on 69 hectares (170 acres) of land, between the airport and the central part of Odessa, Ukraine. Informally named "Tolchok" and officially known as the Seventh-Kilometer Market it has 16,000 vendors and employs 1,200 security guards and maintenance workers.

In Central Asia, the Dordoy Bazaar in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, almost entirely composed of double-stacked containers, is of comparable size. It is popular with travelers coming from Kazakhstan and Russia to take advantage of the cheap prices and plethora of knock-off designers.

In 2011, the Cashel Mall in Christchurch, New Zealand reopened in a series of shipping containers months after it had been destroyed in the earthquake that devastated the city's central business district.[6] Starbucks Coffee has also built a store using shipping containers.[7]

Other uses

Shipping containers have also been used as:

- Affordable housing[8]

- Press boxes

- Emergency hurricane shelters for thoroughbred horses

- Concession stands

- Fire training facility[9]

- Military training facility

- Emergency shelters

- School buildings[10]

- Apartment and office buildings

- Artists' studios

- Stores[11]

- Moveable exhibition spaces on rails

- Telco hubs

- Bank vaults

- Medical clinics

- Radar stations

- Shopping malls[12]

- Sleeping rooms

- Recording studios

- Abstract art

- Transportable factories

- Modular data centers (e.g. Sun Modular Datacenter, Portable Modular Data Center)

- Experimental labs

- Combatant temporary containment (ventilated)[13]

- Bathrooms

- Showers

- Starbucks stores (e.g. 6350 N. Broadway, Chicago, IL 60660 USA)[14]

- Workshops[15]

- Intermodal sealed storage on ships, trucks, and trains

- House foundations on unstable seismic zones

- Elevator/stairwell shafts

- Block roads and keep protesters away, as photo journalized during the Pakistan Long March [16]

- Hotels[17]

- Construction trailers

- Mine site accommodations

- Exploration camp

- Aviation maintenance facilities for the United States Marine Corps when loaded onto the SS Wright (T-AVB-3) or the SS Curtiss (T-AVB-4)

- RV campers

- Food trucks

- Hydroponics farms

- Battery storage units

- Drunk tanks[18]

For housing and other architecture

Containers are in many ways an ideal building material because they are strong, durable, stackable, cuttable, movable, modular, plentiful and relatively cheap. Architects as well as laypeople have used them to build many types of buildings such as homes,[19] offices, apartments, schools, dormitories, artists' studios and emergency shelters; they have also been used as swimming pools. They are also used to provide temporary secure spaces on construction sites and other venues on an "as is" basis instead of building shelters.

Phillip C. Clark filed for a United States patent on November 23, 1987 described as "Method for converting one or more steel shipping containers into a habitable building at a building site and the product thereof". This patent was granted August 8, 1989 as patent 4854094. The patent documentation shows what are possibly the earliest recorded plans for constructing shipping container housing and shelters by laying out some very basic architectural concepts. Regardless, the patent may not have represented novel invention at its time of filing. Paul Sawyers previously described extensive shipping container buildings used on the set of the 1985 film Space Rage Breakout on Prison Planet.

Other examples of earlier container architecture concepts also exist such as a 1977 report entitled 'Shipping Containers as Structural Systems' investigating the feasibility of using twenty foot shipping containers as structural elements by the US military.

During the 1991 Gulf War, containers saw considerable nonstandard uses not only as makeshift shelters but also for the transportation of Iraqi prisoners of war. Holes were cut in the containers to allow for ventilation. Containers continue to be used for military shelters, often additionally fortified by adding sandbags to the side walls to protect against weapons such as rocket-propelled grenades ("RPGs").

The abundance and relative cheapness of these containers during the last decade comes from the deficit in manufactured goods coming from North America in the last two decades. These manufactured goods come to North America from Asia and, to a lesser extent, Europe, in containers that often have to be shipped back empty, or "deadhead", at considerable expense. It is often cheaper to buy new containers in Asia than to ship old ones back. Therefore, new applications are sought for the used containers that have reached their North American destination.

See also

References

- ^ "Brochure_Container_Packing" (PDF). hapag-lloyd. February 1, 2010. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ^ Linnie Rawlinson (February 16, 2007). "Biography: Adam Kalkin". CNN. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Robert Cookson (January 21, 2009). "Hotel changes the landscape of building". Financial Times. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Shipping containers could be 'dream' homes for thousands." CNN. Accessed September 24, 2008.

- ^ Daniel Terdiman (October 25, 2013). "Is Google building a hulking floating data center in SF Bay?". CNET. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Matthew Backhouse (October 29, 2011). "Container mall open for business". New Zealand Herald.

- ^ Falk, Tyler (17 January 2012). "Starbucks opens store made from recycled shipping containers". SmartPlanet. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Constantineau, Bruce (2 August 2013). "Vancouver social housing built from shipping containers". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ "Building a Fire Training Facility". Retrieved 2016-12-20.

- ^ "Costa Mesa Waldorf School is Made From 32 Recycled Shipping Containers". Retrieved 2016-12-20.

- ^ Garone, Elizabeth (2014-11-03). "A New Use for Shipping Containers: Stores". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2016-12-20.

- ^ "This shopping mall in Seoul is made entirely of shipping containers". Business Insider. Retrieved 2016-12-20.

- ^ "Escape From An Eritrean Prison". NPR.org. Retrieved 2016-12-20.

- ^ "Broadway & Devon: Starbucks Coffee Company". www.starbucks.com. Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- ^ Axeman, The (2015-08-25). "The wandering axeman: Making a shipping container into a workshop". The wandering axeman. Retrieved 2016-12-20.

- ^ Day Four: On the trail in Islamabad A photoseries by Musadiq Sanwal shows us what is happening on the streets of Islamabad during the Long March.

- ^ "Shipping Container Hotel". Retrieved 2016-12-20.

- ^ Aaltonen, Riikka (2017-07-14). "Tältä näyttää Suomen ensimmäinen siirrettävä moduulivankila – Oulun poliisilaitoksen väistötilat saivat käyttöönottoluvan torstaina". Kaleva (in Finnish). Oulu, Finland. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ^ "7 Of the Most Inspirational Shipping Container Homes". Granny Flat Finder. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

Further reading

- Books

- Kotnik, Jure (2008). Container Architecture. p. 240. ISBN 978-8496969223

- Sawyers, Paul (2005, 2008). Intermodal Shipping Container Small Steel Buildings. p 116. ISBN 978-1438240329

- Bergmann, Buchmeier, Slawik, Tinney (2010). Container Atlas: A Practical Guide to Container Architecture. p. 256. ISBN 978-3899552867

- Minguet, Josep Maria (2013). Sustainable Architecture: Containers2. p. 111. ISBN 978-8415829317

- Kramer, Sibylle (2014). The Box Architectural Solutions with Containers. p. 182. ISBN 978-3037681732

- Broto, Carles (2015). Radical Container Architecture. p. 240. ISBN 978-8490540558

- Journals

- Broeze, Frank (2002). "The Globalisation of the Oceans: Containerisation from the 1950s to the Present". International Journal of Maritime History. 15. Canada: International Maritime Economic History Association: 439–440. ISSN 0843-8714.

- Helsel, Sand (September–October 2001). "Future Shack: Sean Godsell's prototype emergency housing redeploys the ubiquitous shipping container". Architecture Australia. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- Myers, Steven Lee (May 19, 2006). "From Soviet-Era Flea Market to a Giant Makeshift Mall". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-10-13.