Sack of Magdeburg: Difference between revisions

→Sources: year for Goethe poem |

→Notoriety: year for Goethe ref |

||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

{{Wikisource|The Works of J. W. von Goethe/Volume 9/The Destruction of Magdeburg|Goethe: The Destruction of Magdeburg}} |

{{Wikisource|The Works of J. W. von Goethe/Volume 9/The Destruction of Magdeburg|Goethe: The Destruction of Magdeburg}} |

||

The massacre was forcefully described by [[Friedrich Schiller]] in his 1792 work ''History of the Thirty Years' War''{{sfn|Schiller|1792}} and perpetuated in a poem by [[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe|Goethe]].{{sfn|Goethe}} A scene of [[Bertolt Brecht|Brecht]]'s play ''[[Mother Courage and Her Children]]'', written in 1939, also refers to the incident.{{sfn|Brecht|1939}} |

The massacre was forcefully described by [[Friedrich Schiller]] in his 1792 work ''History of the Thirty Years' War''{{sfn|Schiller|1792}} and perpetuated in a poem by [[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe|Goethe]].{{sfn|Goethe|1801}} A scene of [[Bertolt Brecht|Brecht]]'s play ''[[Mother Courage and Her Children]]'', written in 1939, also refers to the incident.{{sfn|Brecht|1939}} |

||

===Political consequences=== |

===Political consequences=== |

||

Revision as of 07:13, 1 October 2018

| Sack of Magdeburg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Thirty Years' War | |||||||

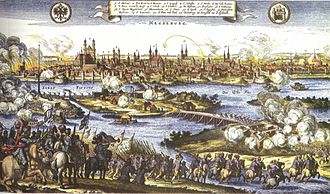

Sack of Magdeburg, 1632 engraving by D. Manasser, putting the blame on the citizens' disobedience | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly Gottfried Heinrich Graf zu Pappenheim |

Dietrich von Falkenberg † Christian William of Brandenburg (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 24,000 | 2,400 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 25,000 inhabitants[1] | ||||||

Location within Saxony-Anhalt | |||||||

The Sack of Magdeburg, also called Magdeburg Wedding (German: Magdeburger Hochzeit) or Magdeburg's Sacrifice (German: Magdeburgs Opfergang), was the destruction of the Protestant city of Magdeburg on 20 May 1631 by the Imperial Army and the forces of the Catholic League. The incident is considered the worst massacre of the Thirty Years' War. Magdeburg, then one of the largest cities in Germany, having well over 30,000 inhabitants in 1630, did not recover its importance until well in the 19th century.

Background

Archbishopric of Magdeburg

The archbishopric of Magdeburg was established as an ecclesiastical principality in 968. In political respect the Erzstift, the archiepiscopal and capitular temporalities, had gained imperial immediacy as prince-archbishopric in 1180. This meant that the archbishop of Magdeburg ruled the town and the lands around it in all matters, worldly and spiritual.

Protestant Reformation

The citizens of Magdeburg had turned Protestant in 1524 and joined the Schmalkaldic League against the religious policies of the Catholic emperor Charles V in 1531. During the Schmalkaldic War of 1546/47, the Lower Saxon city became a refuge for Protestant scholars, which earned it the epithet Herrgotts Kanzlei (Error: {{language with name/for}}: missing language tag or language name (help)), but also an Imperial ban that lasted until 1562. The citizens refused to acknowledge Emperor Charles's Augsburg Interim and were besieged by Imperial troops under Maurice, Elector of Saxony in 1550/51.

Protestant archbishops and Administrators

The Roman Catholic archdiocese had de facto turned void since 1557, when the last papally confirmed prince-archbishop, the Lutheran Sigismund of Brandenburg came of age and ascended to the see.

Openly Lutheran Christian William of Brandenburg, elected to be archbishop in 1598, was denied recognition by the imperial authorities. Since about 1600, he styled himself Administrator of Magdeburg, as did other Protestant German notables assigned to govern principalities that were de jure property of the Catholic church.

Alliance with the Danish king

During the Thirty Years' War, Administrator Christian William entered into an alliance with Denmark. In 1626, he led an army from Lower Saxony into the Battle of Dessau Bridge. After Wallenstein won this battle, Christian William fled abroad. In 1629, he fled to the court of King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden.

As a result of these developments, in January 1628, the Magdeburg cathedral chapter deposed Christian William and elected August of Wettin, 13-year-old son of John George I, Elector of Saxony, as Administrator. This meant little for the moment, however, as Augustus could not assume office due to his father's continued unwillingness to provoke the emperor.

Edict of Restitution

In March 1629, emperor Ferdinand II passed the Edict of Restitution. It was specifically aimed at restoring the situation of the 1555 Peace of Augsburg in ecclesiastical territories that had since strayed from "legal" Catholic faith and rule. Bremen and Magdeburg were the biggest examples of territories to be restituted. From their viewpoint, the Catholic League army under Tilly were enforcing Imperial law against heretic rebels allying with the enemy, during their 1631 siege of Magdeburg.

Alliance with the Swedish king

The city's councillors had been emboldened by King Gustavus Adolphus's landing in Pomerania on 6 July 1630[2]: the Swedish king was a Lutheran Christian and many of Magdeburg's residents were convinced that he would aid them in their struggle against the Roman Catholic Habsburg emperor, Ferdinand II.

Not all Protestant princes of the Holy Roman Empire had immediately embraced Adolphus, however;[3] some believed his chief motive for entering the war was to take Northern German ports, which would allow him to control commerce in the Baltic Sea.[4] Yet the city of Magdeburg had good reason to ally itself with him: the Swedish army was one of the most efficient of the time and Gustavus Adolphus did not rely on mercenaries as much as other rulers. His army consisted primarily of his countrymen, while the armies of the Holy Roman emperor were a mix of Hungarians, Croats, Spaniards, Poles, Italians, Frenchmen, Germans and others.[5]

In November 1630, King Gustavus sent ex-Administrator Christian William back to Magdeburg, along with Dietrich von Falkenberg to direct the city's military affairs. Backed by the Lutheran clergy, Falkenberg had the suburbs fortified and additional troops recruited.

Magdeburg besieged

When the Magdeburg citizens refused to pay a demanded tribute to the emperor, Imperial forces under the command of Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly laid siege to the city within a matter of months.[3]

The city was besieged from 20 March 1631 and Tilly put his subordinate Imperial Field Marshal Gottfried Heinrich Graf zu Pappenheim in command while he campaigned elsewhere.

In fierce fighting, the Imperial troops numbering 24,000 conquered several sconces of the city's fortification and Tilly demanded capitulation.

Assault and sacking

After two months of siege and despite the Swedish victory in the Battle of Frankfurt an der Oder on 13 April 1631, Pappenheim finally convinced Tilly, who had brought reinforcements, to storm the city on 20 May with 40,000 men under the personal command of Pappenheim. The Magdeburg citizens had hoped in vain for a Swedish relief attack. On the last day of the siege, the councillors decided it was time to sue for peace, but word of their decision did not reach Tilly in time.

In the early morning of May 20, the attack began with heavy artillery fire. Soon after, Pappenheim and Tilly launched infantry attacks. The fortifications were breached and Imperial forces were able to overpower defenders and open the Kröcken Gate which allowed the entire army to enter the city, plundering its rich stores of goods. The city was dealt another blow when commander Dietrich von Falkenberg was shot dead by Catholic Imperial troops.[6] When the city was almost lost, the garrison mined various places and set others on fire.[citation needed]

Out of control

After the city fell, the Imperial soldiers supposedly went out of control and started to massacre the inhabitants and set fire to the city. The invading soldiers had not received payment for their service and demanded valuables from every household that they encountered. Otto von Guericke, an inhabitant of Magdeburg, claimed that when civilians ran out of things to give the soldiers, "the misery really began. For then the soldiers began to beat, frighten and threaten to shoot, skewer, hang, etc., the people."[7]

It took only one day for this reign of destruction and death to be completed. Of the 30,000 citizens, only 5,000 survived, most of these having fled into Magdeburg Cathedral. Tilly finally ordered an end to the looting on May 24, and a Catholic mass was celebrated at the Cathedral on the next day. For another fourteen days, charred bodies were dumped in the Elbe River to prevent disease. In a letter, Pappenheim wrote of the Sack:

I believe that over twenty thousand souls were lost. It is certain that no more terrible work and divine punishment has been seen since the Destruction of Jerusalem. All of our soldiers became rich. God with us.[8]

Aftermath

Magdeburg was further weakened by the loss of its wealth and several epidemics as a consequence of the massive destruction. At the time of the Peace of Westphalia, ending the Thirty Years' War in 1648, the city's population had further dropped to 450 people.[citation needed] The number of inhabitants did not reach the former level until the 19th century.

Reactions

After Magdeburg's capitulation to the Imperial forces, there were disputes between those residents who had favored resistance to the emperor and those who had opposed it. Even King Gustavus Adolphus joined, claiming that the citizens of Magdeburg had not been willing to pay the necessary funds for their defense.[9] Pope Urban VIII expressed his satisfaction that "the nest of heretics" was destroyed.[citation needed] However, the Imperial treatment of defeated Magdeburg helped persuade many Protestant rulers in the Holy Roman Empire to stand against the Roman Catholic emperor.[10]

Notoriety

The devastations were so great that Magdeburgisieren (or "magdeburgization") became a common term signifying total destruction, rape and pillaging for decades. The terms "Magdeburg justice", "Magdeburg mercy" and "Magdeburg quarter" also arose as a result of the sack, used originally by Protestants when executing Roman Catholics who begged for quarter.[11]

The massacre was forcefully described by Friedrich Schiller in his 1792 work History of the Thirty Years' War[12] and perpetuated in a poem by Goethe.[13] A scene of Brecht's play Mother Courage and Her Children, written in 1939, also refers to the incident.[14]

Political consequences

Administrator Christian William of Brandenburg was badly injured and taken prisoner. He later converted to catholicism and was released. He received an annual sum of 12000 taler from the revenues of the archbishopric of Magdeburg under the Peace of Prague.

After the sack the archbishopric of Magdeburg went to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria, youngest son of emperor Ferdinand II, as the new catholic Administrator. The Peace of Prague (1635) confirmed his rule over the city, but three years later, Swedish troops expelled the Habsburg army and restored Augustus of Wettin, (first elected in 1628) as Administrator as of October 1638. August finally took full control of Magdeburg in December 1642 after a neutrality treaty was concluded with the Swedish general Lennart Torstenson. He was then able to begin the reconstruction of the city.

The Archbishopric of Magdeburg was secularized and finally fell to Brandenburg-Prussia in 1680.

See also

- In the story of the 1959 novel[15] and 1971 film[16] The Last Valley the Sack of Magdeburg marks a turning point in the life of both main characters. (The captain took part in the looting, losing his faith as a consequence, and the teacher lost his familiy who lived there.)

References

- ^ a b Wilson 2011, p. 471.

- ^ Wilson 2004, p. 128.

- ^ a b Helfferich 2009, p. 107.

- ^ Wilson 2004, p. 129.

- ^ Frusetta 2013.

- ^ Helfferich 2009, p. 108.

- ^ Helfferich 2009, p. 109.

- ^ Medick & Selwyn 2001.

- ^ Helfferich 2009, p. 112.

- ^ Helfferich 2009, p. 113.

- ^ Nolan 2006.

- ^ Schiller 1792.

- ^ Goethe 1801.

- ^ Brecht 1939.

- ^ Pick 1959.

- ^ Clavell 1971.

Sources

- Wilson, Peter H. (2011) [first publ. 2009]. Europe's Tragedy : A History of the Thirty Years War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674062313.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilson, Peter H. (2004). From Reich to Revolution: German history 1558-1806. European history in perspective series. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780333652442.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Helfferich, Tryntje (2009). The Thirty Years War: A Documentary History. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co. ISBN 9780872209404.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Frusetta, James (2013). "Foreign Intervention". In Lampe, John (ed.). Ideologies and National Identities The Case of Twentieth-Century Southeastern Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9786155053856.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Medick, Hans; Selwyn, Pamela (2001). "Historical Event and Contemporary Experience: The Capture and Destruction of Magdeburg in 1631". History Workshop Journal. No. 52. Oxford University Press: 23–48. JSTOR 4289746.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nolan, Cathal J. (2006). "Magdeburg, Sack of". The age of wars of religion: 1000-1650 - An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization. Vol. Vol. 2. London; Westport, CT: Greenwood. pp. 561–562. ISBN 0313337349.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schiller, Friedrich (1792). Geschichte des dreyßigjährigen Kriegs [History of the Thirty Years' War] (in German). Frankfurt am Main; Leipzig: sine nomine. OCLC 833153355.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goethe (1801). – via Wikisource.

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brecht, Bertolt (1939). Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder [Mother Courage and Her Children] (in German). Basel: Reiss (published 1941). OCLC 72726636.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pick, J.B. (1959). The Last Valley. Boston: Little, Brown (published 1960). OCLC 1449975.

- Clavell, James (Director) (28 January 1971). The Last Valley (Motion picture).

: ABC.

: ABC.{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Brzezinski, Richard (1991). The army of Gustavus Adolphus. Men-at-Arms series. Vol. Vol. 1 - Infantry. London: Osprey. ISBN 9780850459975.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Firoozi, Edith; Klein, Ira N. (1966). Universal History of the World: The Age of Great Kings. Vol. Vol. 9. New York: Golden Press. pp. 738–739. OCLC 671293025.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Ingrao, Charles W. (2000). The Habsburg Monarchy 1618-1815 (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521780346.

- Parker, Geoffrey (1997). "The "Military Revolution," 1560-1660--a Myth?". Journal of Modern History. Vol. 48 (2). University of Chicago Press: 195–214. JSTOR 1879826.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Paas, John Roger (1996). "The Changing Image of Gustavus Adolphus on German Broadsheets, 1630-3". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. Vol. 59. Warburg Institute: 205–244. doi:10.2307/751404. JSTOR 751404.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Coupe, W. A. (1962). "Political and Religious Cartoons of the Thirty Years' War". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. Vol. 25 (1/2). Warburg Institute: 65–86. doi:10.2307/750542. JSTOR 750542.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

External links

- Sack of Magdeburg on Filbrun

- Count of Tilly on History of War