Swedish intervention in the Thirty Years' War

| Swedish Intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Thirty Years' War | |||||||

Gustavus Adolphus at the Battle of Breitenfeld | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1630: 70,600 24,600 men garrisoning Sweden |

1632: 110,000 pro-Imperial troops in Germany[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 86,300 killed, captured and deserted | 80,760 killed, captured and deserted | ||||||

The Swedish invasion of the Holy Roman Empire or the Swedish Intervention in the Thirty Years' War is a historically accepted division of the Thirty Years' War. It was a military conflict that took place between 1630 and 1635, during the course of the Thirty Years' War. It was a major turning point of the war: the Protestant cause, previously on the verge of defeat, won several major victories and changed the direction of the War. The Habsburg-Catholic coalition, previously in the ascendant, was significantly weakened as a result of the gains the Protestant cause made. It is sometimes considered to be an independent conflict by historians.

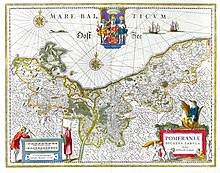

Following the Edict of Restitution by Emperor Ferdinand II on the height of his and the Catholic League's military success in 1629, Protestantism in the Holy Roman Empire was seriously threatened. In July 1630, King Gustav II Adolf of Sweden landed in the Duchy of Pomerania to intervene in favor of the German Protestants. Although he was killed in battle at Lützen, southwest of Leipzig, the Swedish armies achieved several victories against their Catholic enemies. However, the decisive defeat at Nördlingen in 1634 threatened continuing Swedish participation in the war. In consequence, the Emperor made peace with most of his German opponents in the Peace of Prague – essentially revoking the Edict of Restitution – while France directly intervened against him to prevent the Habsburg dynasty from gaining too much power at its eastern border.

Sweden was able to fight on until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 in which the Emperor was forced to accept the "German liberties" of the Imperial Estates and Sweden obtained Western Pomerania as an Imperial Estate.

Religious and political background: The Bohemian Revolt

[edit]

The Thirty Years' War was a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics in Germany. It originated in the co-mingling of politics and religion that was common in Europe at the time. Its distal causes reside in the previous century, at the political-religious settlement of the Holy Roman Empire known as the Peace of Augsburg.[5] The peace was an agreement between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and the Protestant powers of the Holy Roman Empire in the 16th century. It established the legitimacy of Lutheranism[5] in Germany and allowed Dukes and high lords to determine the faith of their fiefdom as well as to expel non-conforming subjects from their territory, the principle known as Cuius regio, eius religio. Additionally, it permitted subjects of a different religion to peaceably move to land where their practices would be recognized and respected.[5] There were also clauses in relation to ecclesiastical lords. When prelates who ruled an ecclesiastical fiefdom converted, the expectation was placed upon them to resign their temporal privileges. Some of these treaty stipulations would be violated on various occasions, as was the case with Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg, Archbishop-Elector of Cologne. Despite various attempts to violate the provisions in the Peace of Augsburg no general European or German conflagration would erupt as a result of the violations. At the end of the conflicts, it was agreed that the provisions of the Peace of Augsburg would once again be adhered to. "All that the Lutheran church gained by the Peace of Augsburg was toleration; all that the [Roman] church conceded was a sacrifice to necessity, not an offering to justice" says one historian.[5] However, the Peace of Augsburg could never be anything but a temporary cessation of hostilities. Its provisions contained an addendum that declared that it would only become active without reservation upon the meeting of a general council and a final attempt at the reunion of the two confessions. There was no reason to believe these would ever happen unless the Lutherans were forced to do so.

Although genuine ideological differences did drive German Princes to convert, the primary motivation of many was often the acquisition of easy riches and territory at the expense of their defenceless Catholic neighbours and subjects.[5] Princes would convert on the grounds that they would be empowered to seize precious land and property from the Roman Catholic Church, and turn that wealth to their own enrichment.

The Protestants understood and accepted as an article of faith that they would have to unite against the Roman Catholic Church to preserve themselves against Catholic encroachment and eventual Catholic hegemony. However, the Protestants were divided. Lutherans held to articles of faith that were mutually exclusive with the articles espoused by Calvinists. The Roman Catholic Church did everything in its power to sow controversy and intrigue between the two major Protestant factions. As a result, there was no political unity of German Protestant states that could coordinate actions against a Catholic interloper.

It was regularly maintained by both religious parties that the other regularly encroached on the spirit or the letter of the Peace of Augsburg.[5] Indeed, it was understood by Protestants that Catholic officials (especially imperial or church officials) were vicious and jealous of the privileges acquired by the Protestants and would do anything in their power to harm the Protestant cause. It was established by practice that the Pope had the power to relieve members of his flock of the most solemn oaths, and it was a matter of principle among Catholics that faith was never to be kept with heretics.[5] On the other hand, Catholics maintained a similar understanding of the Protestants. The avarice displayed by Protestants for Church property[5] could not fail to go unnoticed by even the most indulgent Catholic observer. With such mutual antipathy prevailing between the Protestants and Catholics of Germany, nothing that could would fail to be misunderstood.

Habsburg-controlled domains:

Austrian line

Spanish line

The Thirty Years' War arose out of a regional dispute between Bohemian Protestants and their Habsburg monarchs. Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor was an obstinate and stubborn monarch. His policies forced him into an increasingly weak position with his heterogenous subjects, his court and his family. Forced to make concessions to his Hungarian subjects in order to appease them for his indecisive war with the Ottoman Empire, Rudolf ceded his Hungarian, Austrian and Moravian holdings to his brother, Matthias. Seeing weakness and discord in the ranks of their German overlords, his Bohemian subjects revolted. In 1609, Rudolf granted them concessions with the Letter of Majesty which included religious tolerance and a church for the Bohemian Estate controlled by the Protestant nobility. When the Protestant estates in Bohemia requested even more liberties, Rudolf sent in an army to quiet them. However, Matthias seized his brother at the request of the Protestant Bohemians, only releasing him once he abdicated his Bohemian crown to Matthias. Rudolf II died a couple of months later in 1612, at which point his brother Matthias acquired the rest of his titles, including that of Holy Roman Emperor.

Being without heirs, in 1617 Matthias had his cousin Ferdinand of Styria elected King of Bohemia, a gesture which amounted to naming him as his successor. They were related through their paternal grandfather Ferdinand I. Ferdinand of Styria, or Ferdinand II as he was to become known, was an ardent follower of Catholicism and the Counter-Reformation and not likely to be as willing to compromise as his two cousins and predecessors on the Bohemian throne were or had been forced to do by circumstance. Ferdinand had not received his Bohemian throne in a weak position, as Mathias or Rudolf had. Matthias had acceded to the Protestants' demands to allow Protestant religious facilities to be constructed on Bohemian crown lands. Ferdinand was to reverse the construction of many of these facilities on his ascension to the Bohemian crown, and when the Bohemian estates protested, he dissolved the Bohemian assembly.

The Third Defenestration of Prague was the immediate trigger for the Thirty Years' War. In May 1618, the three estates of the dissolved Bohemian assembly gathered in Prague, the capital of the Bohemian kingdom. Protestant noblemen led by count Jindřich Matyáš Thurn, recently stripped of his title as castellan of Karlstadt by the Emperor, stormed Prague Castle and seized two imperial governors appointed by Ferdinand, Vilem Slavata of Chlum and Jaroslav Borzita of Martinice, and two imperial secretaries. The noblemen held a trial on the spot, found the Imperial officials guilty of violating the Letter of Majesty, and threw them out of a third-floor window of the Bohemian Chancellery. The entirety of these proceedings were without question illegal, not to mention reactionary and partisan in nature.[citation needed] There was nothing even legitimate about the court itself, that it was a lawfully constituted body or that it even had any jurisdiction over the case in question.[citation needed] By happenstance, the imperial officials' lives were saved by them landing in a pile of manure.

The implications of the event were immediately apparent to both sides, who started to seek support from their allies. The Bohemians were friendless, against a powerful monarch of Europe who had many and powerful allies, and who was a scion of one of the most powerful dynasties in Europe who stood to inherit the entirety of the Emperor's dominions. The Bohemians made offers to the Duke of Savoy, Elector of Saxony (the preferred candidate) and even to the Prince of Transylvania. They also sought admission into the Protestant Union, a coalition of German Protestant states formed to give a politico-military unity to the divided German Protestants. The Elector of Saxony's refusal of the Bohemian crown made the Elector Palatine the most senior Protestant available to the Bohemians. In addition to being a Protestant, albeit a Calvinist, Frederick V was married to Elizabeth Stuart and was thereby a son-in-law of the King of England, indisputably the most powerful Protestant monarch, and whose aid it was not unreasonable to hope for.

However the act of unseating Ferdinand – the legitimately chosen monarch of Bohemia[6]- put the Bohemian revolt in a difficult position with the other political powers of Germany and Europe. John George I of Saxony refused the election, and discouraged the nascent revolt.[6] In September of the same year, the Protestant Union met and called on Frederick not to intervene in the conflict. The Dutch Republic, Charles Emmanuel of Savoy and even the Republic of Venice – a traditional enemy of the Pope – sent letters to Frederick informing him that they would not offer him assistance if he accepted the Bohemian crown – but nonetheless, he did.

Background in Sweden

[edit]Gustavus Adolphus had been well informed of the war for some time, but his hands were tied because of the constant enmity of Poland.[7] The Polish royal family, the House of Vasa asserted its right of primogeniture to the Swedish throne – which indeed it had once held. However, when Sigismund III Vasa was elected by the nobles of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, he was elected on the condition that he be a Roman Catholic. Which he was, as he had a mother who was Roman Catholic and had abandoned the religion of his predecessors, however Lutheranism was the primary religion of Sweden, and had by then established a firm grip on the country. It was not solely the result of religious sentiment that Sweden converted. Notably, one of the reasons that Sweden had so readily embraced it was because converting to Lutheranism allowed the crown to seize all the lands in Sweden that was possessed by the Roman Catholic Church. As a result of this seizure and the money that the crown gained, the crown was greatly empowered. In spite of this, he retained his mother's Roman Catholicism as his religion. Although he guaranteed the rights of this religion to the people in his Swedish domains, this was a subject of great contention for the kingdom. Sigismund's right to the throne became a further subject of contention due to his support for the Counter-Reformation. After Sigismund's defeat in the Battle of Stångebro, the Swedish nobility demanded that he rule Sweden from Sweden. Despite their demands, Sigismund returned to his Polish capital, Warsaw, and was deposed from the Swedish throne in 1599.

Gustavus Adolphus' father, Charles IX of Sweden – the uncle of Sigisimund – also a Vasa, was awarded the throne, in part because he was an ardent Lutheran. Soon after, Sweden became engaged in wars with the Kingdom of Denmark–Norway and the Tsardom of Russia. Also, Sigismund III never renounced his claim to the Swedish throne, and for many years the primary direction of Poland's foreign policy was directed at reacquiring it. As a result, Sweden was hard pressed on almost all of its borders. Charles IX died in 1611, without achieving any conclusive result in Sweden's wars during the six years of his reign. At the age of just 17, Gustavus was granted a special dispensation to assume the Swedish crown – and thereby inherited his father's conflicts.

The surrounding powers smelled blood, assuming that such a youth could not maintain the gains that the father had won for Sweden. However, Gustavus had first entered the army at the age of 11,[8] and had first-hand knowledge how to govern a kingdom. His training at statecraft had begun at the same age, when later that year his father permitted him to sit in on meetings of the council of state. The neighbouring powers had not assessed the new king accurately.

The new king was able to bring about conclusive results to the conflicts he had inherited. By 1613 Gustavus had compelled the Danes out of the war after landing on Swedish territory only 10 kilometres (6 mi) from the capital.[9] By 1617[10] he had forced Russia out of the wars and compelled her to cede territory to Sweden.

Gustavus also settled a number of truces with Sigismund – who agreed to them only because of internal strife within Poland. This respite, which lasted 5 years[11] gave Gustavus a free hand to act against the two other powers which had designs on Swedish land. In 1617, he sought to establish a permanent peace with Poland. However, all advances by Sweden for a permanent peace were rejected by Sigismund.

Swedish military and constitutional reforms

[edit]This period of peace with Poland benefited Sweden much, and Gustavus employed it advantageously. He established a military system that was to become the envy of Europe. He drew up a new military code.[12] The new improvements to Sweden's military order even pervaded the state by fueling fundamental changes in the economy.[13] The military reforms – among which tight discipline[12][14][15] was one of the prevailing principles – brought the Swedish military to the highest levels of military readiness and were to become the standard that European states would strive for. The code drawn up encouraged the highest level of personal frugality.[15] In the camp, no silver or gold were permitted anywhere. The King's tent was not exempted from this prohibition.[15] According to one historian, luxury was a "...stranger in the camp..."[16] All soldiers who were caught looting were to be court-marshalled and then shot,[17] nepotism and other forms of favoritism[18] were unknown[17] in the Swedish army. In addition, the system of magazines (a.k.a. supply depots) was brought up to an efficiency unknown in the period.[17] The baggage of soldiers and officers alike – for the speed of movement – was restricted significantly.[17] Garrison duty was required by everyone alike, there were no exceptions.[17][19]

Other reforms were introduced as well, a chaplain was attached to every regiment.[20][21] Prayers were offered up on every occasion before battle. It is related how strange it was to see in Germany, the marshal of high standing in the military establishment kneeling in their religious observations next to the private. Crimes such as thievery, insubordination and cowardice were brought before a tribunal that was overseen by a regimental commander.[20] The last appeal was brought before the king.[21] Provost marshals were introduced and empowered to execute any soldier on the spot who resisted orders.[21] All criminal trials concerning criminality and treason, were required to be tried outside, within the full view of a circle of fellow soldiers.

Decimation was also introduced into regiments that were known to have committed crimes, including fleeing battle.[21] The rest of the regiment was then disgraced by being ordered to perform menial tasks.[20] Violence towards women was punished with death.[20] Prostitutes were absolutely forbidden from camp[21] – especially in the German campaign, as many of them had ties to the German camp as well and divided loyalties could be problematical to Swedish operations. Dueling was forbidden.[22][14] On one occasion – when two men requested leave to duel – the king attended the duel himself and informed the combatants to fight to the death, and that he had a provost marshal on hand to execute the survivor.[20][23]

Although many of Sweden's soldiers descended from the ranks of the traditional landed nobility,[13] a new nobility[13] was being established alongside the traditional nobility of the past. The soldier of merit stood in as high standing as any of the Swedish nobles of the day. Sweden was becoming what had not existed since the days of the Romans, a military monarchy. By introducing this new nobility, the monarchy introduced a center of support in contradistinction to the traditional, landed aristocracy, which thereby allowed it to undercut the authority and privilege of the traditionally independent landed nobility. Sweden succeeded at centralizing, against the very same forces that the Polish monarchy would attempt to do so, and fail against.

The severity of discipline was not the only change that took place in the army. Soldiers were to be rewarded for meritorious service. Soldiers who had displayed courage and distinguished themselves in the line of duty were paid generously – in addition to being given pensions.[20] The corps of engineers were the most modern of their age, and in the campaigns in Germany the population repeatedly expressed surprise at the extensive nature of the entrenchment and the elaborate nature of the equipment. There was a special corps of miners,[24] but the entire army was drilled in the construction of entrenched positions and in constructing pontoon bridges. The first establishment of a general staff took place.[25]

Numerous constitutional changes were introduced to the government in order to foster concord and cooperation.[18] A system of social hierarchy was introduced, and given form under the "House of Nobles".[18] The purpose of this organ was to give more rigid structure to the already existing social order, and aid in effective representation of the respective bodies; those being nobles, clergy, burghers and peasants.[26] To exclude vested and powerful interests from exercising undue influence over the government, the nobles were excluded from holding representation in more than one body. Peers were excluded from debating on motions brought before the body[26] – their attendance was mandatory and they were expected to deliberate on motions in silence.[27] Despite watering down the traditional nobility with a healthy leaven of new nobles based on meritorious military service,[26] the nobility had during Gustavus' reign more channels awarded to it through which it could leverage the operation of the government.[27] On the whole though, the king maintained a monopoly on power within the government.[27]

The government refrained from the debilitating but common practice in Europe, Simony,[28] which benefited the state greatly.

It was with this military establishment that the Swedes were to bring about a conclusive end to the wars with Poland as well as land in and have so much success in Germany.

Break in the Polish Wars

[edit]The Swedish royal family had held for some time claims to Livonia – such claims were of dubious legality but were common in Europe. They were constantly employed by monarchs to justify their attempts to acquire more land. Later in the 17th century, Louis XIV of France would establish a series of courts known as the "Chambers of Reunion" to determine which territories that France had possessed earlier – even as far as the Middle Ages – that were "supposed" to belong to it legally. Using a pretext of just this sort, the Swedes invaded Polish held territories. Sigismund was proving incorrigible as long as he did not retain the Swedish throne. Sigismund had much support on the continent for his claim to the Swedish throne. Among those supporters being the Habsburg king of Spain, Philip III of Spain and Ferdinand II were united to him by bonds of marriage. They were also Catholics.[29] Through intermediaries, Sigismund was able to secure a declaration from Philip's government that all Swedish shipping in Spanish ports were legitimate and lawful prizes of the Spanish crown.[29] Additionally, the Swedish crown was avowedly Protestant, and allied with Dutch Republic, which was actively opposed to Spain at the time.[29] With such supporters, and such measures taken in support of Sigismund's claim, it would be difficult indeed to procure a long-term agreement to cease hostilities.

As a result of his inability to bring the Polish king to some sort of arrangement, war between Sweden and Poland broke out again and the Swedish landed near the city of Riga with 158 ships,[30][12] and proceeded to besiege the city. The city itself was not favorable to the Poles, as they were not Catholic. In addition to this difficulty that the Poles faced, Sigismund's attention was focused on his southern borders, where the Ottoman Empire was making inroads into his kingdom. Embarrassed as he was by this difficulty, he could not relieve the siege taking place. After four weeks, the siege was concluded after the garrison surrendered the city.[11]

He started to march into Poland proper – as the Lithuanian–Polish commonwealth was significantly larger than modern Poland when Sigismund proposed another truce. He did not have the resources necessary to engage in war simultaneously in the northwest and the south of his kingdom.

Gustavus could not persuade the Polish king to a permanent peace of any sort, but Sigismund concluded a truce and granted the section of Livonia that the Swedes had already captured as a guarantee of the truce. Accepting these terms, Gustavus returned to Stockholm in the later part of 1621.[11]

Gustavus had as yet no‑one to succeed him in the case of his untimely death, and his brother, the current heir to the Swedish throne, died in early 1622.[11] Sigismund saw an opportunity in this for his claims on the Swedish throne. He had no navy to invade Sweden with, but was eyeing Danzig, a member of the Hanseatic towns. This city was one of the great trading emporiums of the Baltic at the time, and with this city in his power he figured that he could construct a fleet. The Holy Roman Emperor of the time, Ferdinand II, who had the ear of Sigismund and was his brother-in-law, encouraged him in this ambition. The king, perceiving the advantages that Sigismund would thus gain, in June[31] sailed with a fleet to Danzig and compelled the city to pledge itself to neutrality in the conflict between Poland and Sweden. With Danzig's pledge, Sigismund proposed a renewal of the armistice.[31] Extensions of this armistice would be agreed upon over the course of the next three years.[31]

During this peace, which was to last until 1625,[31] the king worked further in reforming Sweden's military establishment, among which a regular army of 80,000 was settled upon, in addition to an equally great force for the National Guard.

During this time, irregular support had been provided by the Protestant (and non-Protestant) powers of Europe (Kingdom of England, the Dutch Republic)[32] for the Protestant cause in Germany. Both Sweden and Denmark sought to receive aid in order to bring a powerful nation into the German conflict proper, but the terms on which Gustavus proposed had some very definite clauses, and as Christian of Denmark effectively underbid him, support was provided to him.[33] The sum of the Danes' effort was although they achieved some initial inroads into Roman Catholic territory, the Catholic League, under the able General Albrecht von Wallenstein[33][34] (who is reported on one occasion to have told Ferdinand that Gustavus was worse than "the Turk") defeated them at the Battle of Lutter.[34] This resulted in the treaty of Lubeck[34] and the expulsion of any major Protestant combatant from the German theatre. All of Germany was effectively in the hands of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Ferdinand, confident at the turn of events issued the Edict of Restitution.[34] This edict intended to give force to the reservatum ecclesiasticum or the "ecclessiastic reservation" provision to the peace of Augburg. Large portions of land which had been secularized by secular German Lords in the intervening period, but were previously ecclesiastical principalities held by prelates, would thereby revert to former catholic lords/prelates. The Archbishopric of Bremen and the free city of Magdeburg, 12 former or current bishoprics and hundreds of religious holdings in the German states would thereby revert to Catholic control. The edict also allowed for the forcible conversion of Protestants to Catholicism, a direct violation of the Peace of Augsburg.

While no definitive agreement had been brought about with Poland, Gustavus did not contemplate landing in Germany. He wanted to secure his base, Sweden, before he made landing in Germany. He finally settled on bringing the issues with Poland to a conclusion. To this effect, in 1625[35] he again set sail for Livonia. As Danzig, weak to its trust, had allowed a Polish force to garrison it, Gustavus immediately marched his army towards that city. He besieged it in spite of the fact that[clarification needed] and they fought off several efforts to relieve the siege.[35] During this campaign though, the king, wounded on two different occasions, once very severely, was unable to command the army in person. As a result of this, the Swedes suffered some reverses, but nothing materially damaged Sweden's presence. As a result of the king's wounds, the successes of the beginning of this campaign were negligible.

Finally, the king was able to bring a conclusion to the conflict with Poland. In 1628,[36] the king, passing through the Danish sound, a treaty being previously settled that allowed the Swedes the right to do this, landed again. The Emperor sent some forces to support the Poles in their efforts against Gustavus, and it was only at costly results that the Swedes were able to drive this force back and bring a conclusive settlement with Poland. Sigismund agreed to a 5 years truce.

Preparations for the German landing

[edit]

Although the Protestants had initially had some successes,[37] the Emperor commanded all of Germany with the exception of some of the free towns on the North German coast. Including France at this time, there was no concert of action between the Protestant/Anti-Habsburg alliance. This lack of unity contributed to the failure of the Protestant cause. There were no ardent powers fighting for the Protestant cause, all of them only seeking to empower themselves while simultaneously being willing to come to terms with Ferdinand. France promised subsidies to Denmark, but had provided them irregularly.[37] In addition, the Dutch Republic, although ostensibly equally ardent for the Protestant cause as the French, were not keen on seeing the entirety of the Baltic coast fall into the hands of Sweden for economic reasons;[37] which by Sweden's campaigns against Russia and Poland around the Baltic made that intent on the part of Sweden manifest. Lübeck and Hamburg did nothing more than pledge to exchange silver for Swedish copper.[37]

Bogislaw XIV, Duke of Pomerania, pledged his assistance as well, but he was desperately isolated. The Margraviate of Baden as well as William of Hesse also pledged their support.[37] However, even once the Swedes were in Germany they expressed a great deal of reluctance and had to be constantly cajoled and browbeaten into contributing their resources to the cause. The only ardent supporters of the Protestant cause were the dukes of Hesse-Kassel and Brunswick-Lüneburg. These evangelical princes held themselves in complete readiness to join hands with the Swedish. Although little favored the Protestant cause at the time, there was unrest in the entirety of Germany as a result of the horrible atrocities that the catholic armies incurred, on Catholic and Protestant states alike.[40] Everyone alike in Germany, as well as elsewhere in Europe – France, always fearful of the Habsburgs – feared Ferdinand II and the increasing resources that he could bring to bear. France was in favor of Swedish intervention, but because France was also Catholic, and Cardinal Richelieu, France's de facto prime minister, did not desire to openly declare against Catholicism, only offered monetary contributions. However, France refused Gustavus' demands for contributions. He demanded a lump sum upfront, and 600,000 Rixdollars[b](or 400,000 talers[34]) per year subsequently.

Although Sweden lacked many qualities that great powers of the era had: in addition to having the best military force of her day,[41] it also had the most efficiently governed monarchy of Europe. Even there however, there were deficits.[42] Sweden's annual revenues only amounted to 12 million rix dollars per year.[b][41] This situation was ameliorated as the king's reign went on by increasing imposts, and the reversion of lucrative fiefdoms back to the crown on the passage of its holder.[42]

However, several measures were taken to increase the crowns exchequer. Although the crown had been in debt, including the debt taken on to finance wars by the king's predecessors, the king decided to default on all debts which had not been spoken for by the creditors before 1598.[43] The king's father had published an edict in this year which stated all creditors should make their claims on the government known[43] at the risk of forfeiture and proscription. New loans were negotiated from Dutch Republic[43] at the rate of 6 1⁄2 percent. Domestic loans were negotiated for 10 percent.[43] The government was required to provide security on these loans – for obvious reasons. Mortgages were taken out on the crown estates, and the revenues derived from those estates also.[43] The government also legislated monopolies on certain goods, and either collected profits through conducting industry outright through government agents, or through agents who were prescribed to provide the government with certain returns on their exchanges.[44] Salt, copper and later the grain trade were controlled by the government for these exact ends.[45] On the whole, the system of taxation was aggressive, and caused internal turmoil within the kingdom.[46] Taxation improved, leading to an increase in realized revenues.[28]

In addition to the financial difficulties, there were other difficulties confronting Sweden in its race to become one of the pre‑eminent economic and military powers of Europe. Only a million and a half people were living in the country at the time.[41] As a result of this, as his campaign progressed in Germany, he came to increasingly rely on German mercenaries. Although these German mercenaries were well known for their atrocious conduct towards the local population, under the Swedish military system they were later brought to the Swedish standard of discipline.

The king called a convocation of the most eminent men of the state, and after arguing his case before them, it was agreed that Sweden should intervene in the pseudo-religious conflict in Germany. It was his belief that after Ferdinand had settled affairs in Germany to his satisfaction, Sweden would be next on his programme.[41] There were several pretexts for landing in Germany as well. The Habsburgs had actively aided the Poles in their conflict with Sweden – although the two were at peace with each other.[41] In addition to this the conference that had taken place at Lübeck – a conference that had sought to settle the issues that precipitated the war – had dismissed the Swedish envoys – at the behest of Wallenstien – out of hand.[41][47] When they refused to leave, they were threatened with violence.[47] This angered the king greatly. Lastly the king, as well as the nation, did feel deep concern for the Protestants who were being ruthlessly oppressed. One historian says, "Ferdinand had also insulted the Swedish flag, and intercepted the king's dispatches to Transylvania. He also threw every obstacle in the way of peace between Poland and Sweden, supported the pretensions of Sigismund to the Swedish throne, and denied the right of Gustavus to the title of king.... So many personal motives, supported by important considerations, both of policy and religion, and seconded by pressing invitations from Germany, had their full weight with a prince, who was naturally the more jealous of his royal prerogative the more it was questioned, who was flattered by the glory he hoped to gain as Protector of the oppressed, and passionately loved war as the element of his genius."[47]

Stralsund, a member of the Hanseatic towns, was being hard pressed by the Imperials. This area could not be left to the Catholics without leaving the serious possibility of the Holy Roman Emperor invading Sweden. As long as he was not personally on the scene to prevent such an acquisition, it was only a matter of time that these areas should be seized. The Emperor had 170,000 troops,[48] of various qualities to be sure, in Germany. Such an army could not be prevented from seizing these places with the minimal resources that were at the command of the Protestant holdouts.

Preparations were therefore made between 1629 and 1630.[49] Nitrate (saltpetre) and sulphur were gathered in large qualities in anticipation for the campaign.[c] There was to be enough of this that each regiment could be furnished with the quantity that it would need each month.[d] Factories that produced swords, armor and other weapons were kept at full capacity.[51] A war tax was also implemented, which was specifically aimed at taxing the nobility to ensure that everyone was contributing their part.[49] During this first year, three-quarters[49] of the revenue that was accumulated by the state was to be directed towards the war effort. Even the churches were given instructions to preach in favor of the cause and conscription.[46][49] All males from the ages of 16 to 60 were called upon to report for service.[46] Those who could not report regular wages were among the first to be incorporated into the ranks.[49][46] Only families that could report at least one son were required to furnish soldiers.[49] If a family could not report sons, then they were let off from service. No exceptions were granted to nobles[52] – they were required to serve in the cavalry.[52] Men were also incorporated into the army from abroad. There were two regiments of Scots,[49][52] many soldiers were incorporated into the ranks from the Danish army that had been defeated at the hands of the Habsburgs.[49] Ambitious mercenaries everywhere enlisted in the Swedish army, when the king's military prowess started to become well known throughout Europe.[52] The Hanseatic towns also furnished contingents for the upcoming conflict.

There were also considerable reserves, already encamped in certain parts of eastern Germany.[49] There were 6,000 men distributed between the island of Rügen and the city of Stralsund, both of which were under the command of Leslie – a general who had already proven his ability. Leslie himself had been active in recruiting from the Hanseatic towns.[49] There were stationed in the occupied parts of Prussia and Livonia an additional 12,000 men.[49] These were under the command of Axel Oxenstierna – a man whom held the absolute confidence of the king and was the government's first minister[49] – by the end of the year these forces were brought up to 21,000 men.[49] In order to hold Sweden and its subsidiary states firmly, there were stationed in Sweden itself 16,000 men.[51] In case there should be any contingency that should arise from Finland and the east, 6,500 men were left there.[49] In the Baltic provinces there was a further 5,000 men. Gustavus believed that it was absolutely essential that he should hold the entirety of the Baltic coast, because he would be no good in Germany if the Catholic powers could operate on his lines of communication and threaten his throne. In total, there were 76,000 men enlisted in the Swedish service. Of whom, 13,000 were destined to make the initial landing on German soil.[49] These forces were further reinforced by 2,500 men from Sweden,[49] and 2,800 men from Finland once the landing had taken place. The army consisted of 43,000 Swedes and the rest were recruited from other nations. 3% of the total population of Sweden was therefore designated for the campaign – if the population was divided between males and females evenly – then 8% of the male population was serving in the ranks for the initial campaign – no doubt a heavy burden on the state.

The cost to the Swedish exchequer was in excess of 800,000 rix dollars[b] per year.[53] The king, not knowing of the recalcitrance of his Protestant allies, counted on receiving considerable contributions from them as well once he was on German soil. With the 13,000 men allocated for the German landing, the king had two armies to contend with (one being under Wallenstein and the other being under Tilly) that he assumed to have 100,000 men each.[53] The king was seriously gambling on recruiting more men in Germany. His troops however, were of the highest quality, and once he had gained the confidence of the Protestants by winning battles and seizing important places, he did not doubt that he would receive more.

The landing: Wollin and Usedom

[edit]The king made no formal declaration of war against the Catholic powers.[49] After the attack that had taken place on Stralsund, his ally, he felt that he had sufficient pretext to land without declaring war.[53] He did make attempts to come to an agreement with the Emperor,[53] but these negotiations were not taken seriously by either side.[53]

The capital of Pomerania, Stettin, was being seriously threatened by the Emperor's forces. In order to save the town, the king deemed it essential that he should land here right away. He planned to land there in May 1630,[53] but because the winds were not favorable to sailing out, the Swedes waited three weeks before departing. There were 200 transports[53] and 36 ships employed to guard the armada while it made its landing.[53] The king proposed that he should land his armada at the Oder delta and treat with each of the cities in the vicinity to gain firm grip on the country before making any inroads into the interior of Germany. His plan, once he had established himself, was to march up the Oder.

The king gathered knowledge of the vicinity in which he was to land. He made himself intimately familiar with it. Despite being Protestant, Bogislaw XIV, Duke of Pomerania, was treating with Ferdinand. Bogislaw was engaging in negotiations with both sides in order to preserve his title to the duchy and the integrity of the duchy itself, as well as its financial viability. His chief concern was to ensure that the depredations that were being visited on much of Germany would not be committed in his duchy. When he learned of Gustavus' intention of landing in Germany, in his duchy, he reached out to the king and requested that the king should not make war in his duchy. The king informed Bogislaw that he was going to land in his duchy, and that upon his conduct depended how the duchy was to be treated. He informed the duke that depending on his conduct, he could count on the Swedish army being lenient towards his duchy or severe in how it was handled.

Three days of public fasting and prayer were declared in order to ensure the success of the landing.[54] The king made the final arrangements for the government of his kingdom. First of all he ensured that his three-year-old daughter, Christina, would be his successor in the event of his death.[e]

The landing transpired on 4 July near Peenemünde on the island of Usedom. He immediately captured a number of the important towns on the island and garrisoned them. Disembarking on the island, the king slipped and fell,[54] but nothing was made of this by the army. The first thing the king did upon landing was kneel and offer up prayers in thanks for the success of the landing. Immediately after offering up these prayers, the king picked up a shovel and started to dig entrenchments that were going to cover the landing.[54] It took two days for the entire force to land,[54] as the companies were landed they were immediately put to work in creating these entrenchments. There were some older entrenchments that were already there, and these were seized as well. Other ones were also constructed.

Since it had taken so long for the armada to disembark, the stores of food that had been designated for the army upon landing had been largely consumed by the army.[54] Orders were issued that food should be gotten from Stralsund, but even these were not enough.[54] The king, angered by this lack of victual, held Johan Skytte (previously the king's tutor), the officer who had been in charge of ensuring the supply of food to task for this and lectured him severely.[51] He sent to Oxenstierna and ordered him to hurry up supplies from Prussia.[54] Feeling confident that he had secured his landing, by the end of the month, the king sent to Oxenstierna a small portion of his fleet to gather supplies and bring them to his position at the delta of the Oder.[54]

After two days, the king took 1,200[54] musketeers and a force of cavalry with him. He moved this force to the region opposite Wolgast (a town that was on the continent proper opposite Usedom). Seeing that the Imperials had constructed a fortress to protect the region he reconnoitered the fortress, observing its strengths and weaknesses. He sent back to his principal base and ordered that 4,000 additional musketeers be brought up to the position.[54] When these came up, he moved towards the fortress but found that the Imperials had abandoned the base and moved to Wolgast.[54] He left 1,000 men in this base and with the rest of the force, 3,500 foot soldiers and 2,500 cavalry,[54] he set out to clear Usedom of Imperial forces entirely.[54] There were a number of bases opposite Usedom on Wolin,[54] which Imperials retreated to as the king made his push to clear the island.[54] He ordered that his forces garrison these bases and continued to pursue the Imperials to the far side of the island.[54] There was no resistance on the island, as the Imperialists continued to retreat.[54] Seeing that they would soon be pinched between the inlet that separated Wolin from the mainland, the Imperials burnt the bridge that crossed from Wolin to the mainland and continued their retreat.[54] The king had secured both Wolin and Usedom – as the result of which he controlled all of the mouths that the Oder had into the Baltic Sea, he went back to his headquarters.[54]

Securing Pomerania

[edit]

Stettin was the capital of Pomerania, and one of the reasons that it was selected as the capital was because it was centrally located in the duchy. The duchy itself was divided roughly in two by the Oder. It had been under siege by the Imperials for some time but the Imperials – as was common for sieges at the time – had not made significant progress in taking the city. Generals of the time deemed sieges to be difficult and ill-advised. To this effect, Stettin was still in the hands of Bogislaw – having held out against many vigorous assaults.[55] Learning of Gustavus' landing however, the Imperial generals retreated (Savelli southeast of Stralsund[55] further north on the Oder)[55] from the Swedes. Savelli retreated to Anklam[55] and Conti retreated to Gartz and Greifenhagen[55] (holding both banks of the Oder). Gustavus left Colonel Leslie in command of Wollin and General Kagg on Usedom.[55] Both of them were left under the command of General Knyphausen. He took provisions to ensure that these islands would be secure from landings by the Imperials.[55]

The king drew in the 5,000 soldiers that he had garrisoned in Stralsund and assembled the rest of his forces and brought them up to a total of 74 companies.[55] By 18 July,[55] he had assembled this force and the next day he set out from the Swine Inlet to Stettin.[55] He was squarely between Savelli and Conti, and once he was able to acquire the city, he would have established himself on interior lines.

This is important because he would have a shorter period of time to bring his troops to any given point, and would therefore be able to reinforce any position that was threatened more quickly than the Imperials if they should attack a sector that he had taken. In addition, he would be able to apply pressure to any point in the Imperial line more quickly than the Imperials themselves could apply to his line. This was especially important because at the present he did not have as large of a force as the Imperials did. By having this position he would be able to march his troops between both his lines as necessity required.

In spite of his city being harassed by the Imperials, Bogislaw was focused on maintaining his neutrality in the conflict.[56] Colonel Damitz, who was in charge of the defense of the city, had received orders not to admit the Swedes into the city.[56] If necessary, the duke ordered him to attack the Swedes. A drummer was sent to treat with the king;[56] however, the king did not receive the ambassador, stating that he did not recognize messages that came from soldiers of such low grade, and that he would only speak with Damitz himself. Some talks took place between the king and the colonel; however the colonel had not been empowered to allow troops to enter the city.[56] The king and the duke quickly made arrangements to speak, and at the meeting the king informed the Duke that he would not brook neutrality from any power in Germany, and that he was fully prepared to take the city by force.[56] He was also informed by the king that the Swedes would not tolerate delay of any sort, that he must be allowed to enter the city at once.[56]

On 20 July, after having persuaded Bogislaw that he should be allowed to enter the city (up to this point, there had not been a single Swedish casualty), the Swedes marched into the city.[56] A treaty was concluded between the two powers, which effectively stripped Pomerania of its sovereignty, and other matters of the city and duchy were settled to the king's satisfaction.[56] The king then received contributions from the duke and swapped out Damitz' force and placed three of his own companies to garrison the city.[56] Bogislaw sent an embassy to the Emperor, informing him of the situation that had just transpired, but the Emperor declared that the entirety of Pomerania was in revolt, and looting and pillaging in the country was permitted on an even more extensive scale.[56]

Shortly thereafter, the king received additional reinforcements from Prussia.[56] So bad were the conditions prevailing in Germany at the time, many other men voluntarily enlisted into the Swedish ranks – it was easier for a villager to get food within an army then if he were living in the countryside.[56] With the acquisitions the Swedes had made, they were now up to 25,000[56] soldiers. Although there was much support for the Swedes in the German countryside, there was also significant enmity to the Swedish cause. During this time there multiple attempts made to assassinate the king by Catholic enthusiasts.[56]

The king then ordered that the defenses to Stettin be improved. All of the people of the city as well as villagers were rounded up and the defensive works were quickly completed.[56]

Despite the advantageous position that the Swedes had acquired, they were still vulnerable.[57] At Wolgast, opposite Usedom, there was an Imperial force preparing to attack the Swedish on Usedom.[57] In addition, there were Imperial camps established at both Garz and Griegenhagen,[57] they also still held Damm – opposite of Stettin[57] – and as long as this city was in Imperial hands the possession of Stettin was not an established fact.[57] On 22 July,[57] the king ordered a squadron to capture this city. After taking it, the king ordered Damitz – the colonel of Bogislaw – to take Stargard.[57] This city was taken, and shortly after Treptow and Greifenberg were also taken. A number of other cities were taken in order to ensure that the Imperial force that was at Kolberg could not join their comrades via Greifenhagen and Garz. The king was careful to garrison these cities to ensure that the Imperials at Kolberg should not punch through his line and join their comrades.[57] The king's next objective was Garz, and one day while observing the area an Imperial patrol came across him and his guard and they were captured.[57] Not knowing who he was though, they did not take due precautions, and his main guard quickly attacked and saved the king.[57] The king was so reckless about his own personal security that this happened on two different occasions during the course of his career.

The next city on his programme was Anklam. Savelli had stationed himself there upon the Swedish landing. The city was on the opposite side of Usedom, and although there were no bridges between it and Usedom, it still posed a significant threat. it would easily serve as a place from which the Imperials could cross onto Usedom. However, the Imperials retreated from this city too, so confused was the king by this that he warned the general whom he had detailed to take the place, Kagg, that he should be on the alert for a rouse of some kind.[57] Kagg took the city and fortified it without incident.[58]

Ueckermünde and Barth (to the west of Stralsund) were also taken without incident.[58] Wolgast was besieged, and although the garrison gave up the city to the Swedes they held out in the citadel of the city.[58] This garrison hung onto the citadel until 16 August.[58] Treptow[57] was also taken.

The king did not only desire to tighten his grip in the area he had landed in, but he also wanted to join hands with Oxenstierna. Oxenstierna had a large force on hand in Prussia which the king wanted to bring into the conflict in Germany (Prussia, being a fief of Poland at the time). The king instructed Oxenstierna to order an "able officer" to Stolpe, but establishing a connection with Prussia and Oxenstierna would have to wait. Despite his good position, being in between the Imperials as he was, his army was spread out in three separate bodies that could not support each other except by sea; under the king was the force stationed at Oderberg and Stettin; Kagg's force was based on Usedom (a sort of "link in the chain"[58]); and Knyphausen's force that was based on Stralsund.[58] It was critical that before he advance into the interior, or that Oxenstierna should join him, he should be able to act in concert with all of these bodies and move them about at will so they could support each other without encountering the enemy en route. One of the features that makes him the first "modern general" is his scrupulous care for his communications and his operating under the principle that his army should be united, or each unit having the ability to join the other units, in good time. Holding Anklam was not enough to ensure that the body based on Stralsund could quickly join his army at Oderburg should matters become problematical. The line from Stralsund to Anklam down to Stettin could be punctured at any point. The river Tollense (immediately west of Anklam) ran roughly parallel to this irregular line that he had garrisoned. To hold his gains on the coast secure, he must have this river as to prevent the Imperials-based out of Mecklenburg[58] from cutting his line. To change this situation, the king ordered Knyphausen to move his army forward in a southwesterly direction towards the Tollense,[58] and Kagg was to follow Knyphausen's movement and simultaneously ensure that Knyphausen's force was not attacked on its northern flank. As the line was spread out as it was, with a somewhat weighted right flank, it would ensure that the Imperials could not support each other, as the original units would be forced to hold their position or risk losing their positions in their attempt to save another fortified place.[58]

Savelli was still at Greifswald,[59] and when he learned of the occupation by a small Swedish unit at Klempenow, he sent a small detachment to observe it.[59] Upon learning that Wolgast had fallen, sensing that he was being surrounded, he marched his army by way of Demmin on to Klempenow. As there were only 100 men stationed in the city, it fell.[59] Only one officer and six men surrendered.[59] Seeking to tighten his grip on the Tollense region, as having been driven out of Greifswald, it was effectively his new line; he garrisoned Klempenow,[59] Loitz and Demmin.[59] He also garrisoned Neubrandenburg, Treptow and Friedland.[59] He ordered Pasewalk taken, a small town outside of Stralsund, and despite fierce fighting the place was taken and the town was burned to the ground.[60]

Meanwhile, stationed at Pasua and Elbing (to the far east), Oxenstierna was seeking to move towards the king. The cities that were critical to establishing a land route between the two armies was Kolberg (occupied by the Imperials) and Cammin. Knyphausen and Oxenstierna were entrusted with the task of establishing a land route between Prussia and Swedish occupied Pomerania.[61] Meanwhile, being August as it was, the king was contemplating the establishment of winter quarters.[61] However, the Administrator of Magdeburg, Christian William declared in favor of the Swedish, drove out the Imperial garrison and called the Swedes to aid the city. This was done without the king's prior knowledge, and there were many objects which the king deemed to be of higher importance than the city of Magdeburg. It is not likely the king would have encouraged such a move if he had been consulted about it. The king still wanted to march to the Elbe,[61] take possession of the duchy of Mecklenburg and engage in negotiations with Hamburg and Lübeck. Magdeburg was much too far away, and there were large contingents of Imperial troops between the Swedish army and Magdeburg. However, the king sent a colonel, Dietrich von Falkenberg, to the city and ordered him to bring the city into the highest level of defense for an anticipated siege by the Imperials.[62]

This put the king in a difficult position. If he left Magdeburg to its fate, then he would be seen by the Protestant powers of Germany as being unreliable and being unable to support his allies. They were already reluctant enough to support the Swedish and provide manpower and material. If he was seen in this light by the Protestant powers, then they would be even more inclined to withhold their support.

Mecklenburg

[edit]

By September 1630, King Gustavus was confident that he had secured himself on the coast of Germany. Desiring to reach out west, he had a number of reasons for doing so: he wanted to restore his cousins to their duchies in Mecklenburg (whose territories had been taken from them by Ferdinand and given to Wallenstein for his services);[63] to establish a firm connection with the duke of Hesse-Kassel, who was the only prince at the time that had provided support to the Swedish – he was essentially the only wholehearted ally that he had in Germany;,[63] to reach Magdeburg (if at all possible);[63] reach out to the duke of Saxe-Lauenburg who had assured him that he would be received warmly (only if he reached his duchy);[63] and to establish contact with Lübeck and Hamburg.[63] Although this route, with Magdeburg in mind, was indirect, it was the only route he could take without passing through Electorate of Saxony and the Electorate of Brandenburg (which was also in the hands of the same family that possessed Prussia). These princes, desiring to maintain the integrity of their dominions and their ostensible neutrality (the Imperials had forced them to allow armies to march through their territories on several occasions, and would do so again) did not want armies, especially Imperial armies, marching through their territories and causing destruction in their lands.[63] These two German powers were also Protestant. They were awaiting events to see who would gain the upper hand, and they too were duplicitous in their dealings with both sides. Both of their princes were just as suspicious of the Swedes as they were of the Imperials. They were both powerful German states, and could not be ridden over roughshod the way Pomerania had been. The king was accordingly more cautious in his dealings with them and courted them with the desire of attaining an alliance with them.

With Magdeburg in particular in the back of his mind, in order to move towards his potential and actual allies, without invading Saxony and Brandenburg, the king saw that Wismar and Rostock would be necessary to take. Wismar was especially important because it allowed him to incorporate more of the Baltic sea within his control, and would allow him to exclude inimical fleets from the Baltic by preventing them from having a place to land to resupply.[63] Gustavus Horn had brought reinforcements from Finland and Livonia.[63] He left these reserves, as well as the majority of the army stationed at Stettin, under Horn.[63] The king issued him orders that he was to hold the place securely, he assigned him the task of taking Greifswald before the spring[63] and to hold on to the road between Stralsund and Stettin. If the Imperials were to march on him directly with a numerically superior force, he was to abandon the project of Greifswald and protect the Stettin–Stralsund line and march towards the king.

Leaving Stettin on 9 September, the king landed at Wolstack. He quickly arrived at Stralsund in anticipation for his advance on Mecklenburg. Although he anticipated reinforcements from Prussia, all that was on hand were the Finns and the Livonians that had been brought up by Horn.[64] In addition, there was sickness in the camp.[64] Every sixth man was sick in this force that was to invade Mecklenburg[64] From here he set sail in the direction of Ribnitz towards Rostock.[65] He then captured both Ribnitz and Damgarten.[65] While here the king learned that there was an army assembling at Demmnitz in the east. This worried the king, and as a result of which he abandoned his scheme of taking Rostock.[65]

However, a turn of events took place that would aide the Swedish further. A congress had been in session at Ratisbon for the last six months,[65][66] and one of the consequences of this Congress was that Wallenstein was dismissed. Many of the potentates in Germany were prejudiced against him, because of the license he allowed his troops in their dominions. There was a personal rivalry between him and the Elector of Bavaria which also contributed to this. One historian says, "The anxiety with which Wallenstein's enemies pressed for his dismissal, ought to have convinced the emperor of the importance of his services... many armies could not compensate for the loss of this individual".[67] However, despite the unprecedented victories that Wallenstien had brought him, and his virtually unassailable position, he was politically vulnerable and needed to appease the German princes pressing him for Wallenstein's dismissal. The Emperor's son, Ferdinand, had already secured election to the Kingdom of Hungary, and was in the middle of the procedures around securing his election as the next Holy Roman Emperor.[68] The Catholic and Protestant princes (and specifically electors) were unanimous in their outrage and exacerbation with Wallenstein and his mercenary army, and were in a position to leverage the Emperor's action in a material way. Maximilian's support for his son's election, [68] was critical, so Wallenstein had to be abandoned for the sake of assuring his son's succession.

Tilly was rewarded with the command, but a large part of the Imperial army, being mercenaries as they were, had been under contract to Wallenstein personally,[66] rather than to the Emperor. As a result of this, upon the dismissal of Wallenstein the mercenaries that were under contract to Wallenstein dispersed. Many of these soldiers would enlist in the Swedish service, and it is related that they were quickly brought up to the Swedish standard of discipline.[65] The king deemed Wallenstein to be such an able general, that upon learning of his dismissal, he reached out to him and requested that he serve under him.[65] The Catholic cause had lost an able general. Additionally, the army which he headed, 100,000 strong, was entirely under his command.[69] Both the officers and the men were personally loyal to him.[69] The majority of the officers in the main army quit the imperial service.[70]

Temporary setbacks

[edit]Turning his sights away from Rostock for the time being, the king determined that he must take the Tollense river before progressing. However, before doing this he decided to definitively settle the Kolberg question, and opted, instead of continued observation of the town, to take it. This was so he could communicate completely with Oxenstierna. Horn, the general who had been allocated to command the Kolberg region and see about the taking of Kolberg itself, was informed of an Imperial plan to march to Kolberg from Garz and relieve it.[65] Horn assembled all of the forces that he could, leaving a small force to observe Kolberg, and marched towards Rossentin,[71] immediately to the south of Kolberg[71] to await the arrival of the Imperial army from Garz.[71] The Imperials, hoping to avoid detection, marched via an elaborate circuit to the south.

However, their movement and subsequent attack was repulsed, and they retreated. However, the Imperials were eager to take and relieve the city, and expecting to catch the Swedes off guard, contemplated another move on Kolberg. For whatever reason, during the beginning of this plan it lost impetus, and the army that was marching to relieve Kolberg became disorganized. Upon arriving on the eastern side of his new acquisitions, the king assembled his generals, got all the knowledge from them pertaining to the dispositions of the enemy forces, and resolved to attack Garz. The time for wintering his troops was nearing, but he desired to strike a blow to the Catholic cause before taking to camp for the winter.[72]

The army moved mostly down the right (east) bank of the Oder towards Gartz. There were also troops on the left (western) bank that were kept in constant communication with the main army via the naval force that was to keep the two armies in communication with each other. Moving towards Greifenhagen first, when the Imperial general in command of the city observed the army coming to his position he deemed it to be nothing more than a salvo that was typical of the Swedes to distract him. However, the Swedes camped in a nearby forest, and the next day, on Christmas Day, after a solemn observation of religious traditions was observed, the attack was begun.[72] A breach was made in the Greifenhagen fortifications, and the king in person[72] led the first assault. After this place was successfully assaulted, the Imperial troops here started to retreat towards their comrades in Western Pomerania.

The next day the king marched his army towards Garz, in preparation for battle in battle order, but the Imperials soon retreated.[72] They moved to the south in a southeasterly direction, certain units were detailed to hold Custrin and Landsberg, in order to ensure that they were not cut off from Frankfurt. The king sent units towards these cities to prevent the retreat of the Imperials, but Landsberg the king deemed to be too strong to assault. Satisfied with this victory, his army marched back to Neumark Konigsburg.

Frankfurt

[edit]Having taken Gartz and Greifenburg, which if utilized properly could lead the king, through Prussia and Silesia into Ferdinand's hereditary possessions, the king left Horn with six regiments of infantry and six of cavalry.[73] These were faced towards the Warta river,[73] with orders to keep the enemy pinned in the Warta country between the Landsberg and Küstrin neighborhood.[73] Instructions were left to Horn not to engage the enemy outright, to act strictly on the defensive against a numerically superior enemy and if the opportunity should arise, seek to seize Frankfurt and Landsberg.[73] His reserves were stationed in Pyritz, Stargard and Gollnow.[73] These were stationed there so that he could retreat towards them if a numerically larger foe should present itself against his front at Soldin,[73] while simultaneously protecting Swedish gains along the right bank of the Oder and Eastern Pomerania.[73]

The king set out from Bärwalde to Stettin, crossed there and accumulated 12,000 men.[74] From Stettin he marched through Germany towards Prenzlau, Neubrandenburg.[73] Taking Neubrandenburg, the Imperial garrison at Treptow also retreated for fear of being captured.[74] The next day Klempenow was also taken.[74] These towns were important, because they could prevent any Imperial armies from advancing north to relieve Demmin. Upon taking Demmin, the king would hold the entirety of the Tollense river.[73] This he had set out some time back to do, but had been distracted from the project. Being winter as it was, the king could afford to take up a project that was comparatively conservative in scope for a winter campaign as such that he was in the process of conducting. In addition, in spite of the fact that it was winter, it was important that he should establish a firm base between the Stralsund and Stettin country. With this line secured, his proposed expedition into Mecklenburg would be more secure.[73]

Demmin was at the confluence of three rivers, and the ground was something of a bog.[73] As it was mid-January significant portions of the area were somewhat frozen, and this aided the Swedish in their siege of the place.[73] Knyphausen, who was at that time stationed at Greifswald and besieging it, was ordered to come south and aide in the siege at Demmin.[73] Loitz, and city that is in between Greifswald and Demmin, had to be taken first though, as it was in the way. The king took it before sitting in front of Demmin, and after having taken it he urged Knyphausen to come as quickly as possible.[73] In addition to making room for Knyphausen's army to come up on eastern side of Demmin, it also blocked Greifswald and left it completely without aid.[73]

As a result of this manoeuvre Tilly was placed in a difficult position. He wanted to go straight ahead towards Mecklenburg, but if he left only the reserve he had in the Landsberg country (8,000 men),[73] then he feared that Horn would push these reserves out of Landsberg and establish the Swedes on the Warta river. Inversely, if he stayed here to protect the Warta line (which if opened would give the Swedes free access into the hereditary lands of the Austrian emperors), then the Swedish would have an easy time of marching into Mecklenburg over the Havel and relieving the siege at Magdeburg.[73] Tilly deemed it important to take Magdeburg, as taking it would be an impressive moral victory over the Swedes and, he thought, it would keep the Protestant powers of Germany cowed.[75] Additionally, Maximilian I, Duke of Bavaria was pressuring him from Dresden to strike a decisive blow by taking this city. Strategically, he wanted to ensure that Demmin wasn't taken. Since the Swedes had all the towns that were on the most direct route between Frankfurt and Demmin, he made a circuit to the south.[75] This allowed him to simultaneously move towards his objective and at the same time ensure the siege of Magdeburg continued by quickly gaining a secure footing on the Havel from which he could prevent the Swedes from relieving Magdeburg.[73] However, in addition to making this indirect route, he had to march through the Electorate of Brandenburg as tenderly as possible. As Brandenburg had not declared for either side, it still retained a neutrality, but only in the technical sense. Enough so that Tilly could demand to march through the Electors territory, but sought to alleviate the worst of the enmity this might arouse in the elector by avoiding his capital, Berlin.[75] After making this "tender" march, he finally arrived in Neuruppin.[75] As the Havel was behind him, he had achieved one of his objectives, that of keeping Magdeburg safe. However, from this position he now marched north in order to help relieve Demmin.

However, Tilly was not able to come to the support of his subordinate in time. After two days of sitting before the city, Savelli believed that he could not hold Demmin, and surrendered on condition of his army not serve in Pomerania and Mecklenburg for three months.[75] This city was well stored, as it had anticipated holding out for a while against a Swedish siege. However, as the city was given up after only two days, the Swedes gained all of the provisions.[75] Among the baggage that was discovered, which as per the agreement was to be returned to the Imperials, were the possessions of a Quinti Del Ponte,[76] a man who had served under the Swedish but was paid to betray them and then deserted.[76] The king was asked what he would like to do with him, but he stated that he had no intention of taking petty revenge.[76]

With so much success in Pomerania, the estates in the duchy were finally roused to action, and offered their support to the Swedes.[76] 10,000[76] infantry and 3,000 [76] cavalry were offered to garrison the duchy itself. This was valuable because the Swedes would be able to free up men from garrison duty and bring them into the field.[76] In the face of the Imperial armies, and their sheer size, this was a sorely needed acquisition.

Although the king was seriously considering wintering his troops at the present, he himself, as well as Knyphausen, came to believe that Tilly was contemplating a march on Neuruppin in an attempt to relieve the siege that was taking place at Greifswald. As the siege was important and he didn't want to lighten up the impetus of the siege taking place, he ordered Horn to march towards Friedland[77] in order to ensure the Knyphausen did not have to move troops away from the siege to prevent Tilly from reaching Greifswald.[77]

Kolberg had previously fallen, and Gustavus believed that the manoeuvres by Tilly were designed in part to compensate for this loss. Which was indeed a blow to the Imperialist cause. The king moved back to the Oder, thinking that it would draw Tilly away from his advance towards the siege, Stralsund and Stettin. He proposed marching on either Frankfurt or Landsberg. Tilly does not seem to have paid any attention to this manoeuvre.[78] Instead he marched towards Stargard, the one just south of Neu–Brandenburg. Stargard was not a place that could be easily defended, the king did not believe in the strength of the position, and informed Knyphausen of this. He had ordered Knyphausen to plan on retreating after an honorable period of time, but the messengers had been seized and Knyphausen held out to the last. The city was breached, and only Knyphausen and three other man survived the siege. The subsequent looting of the city was allegedly horrible.

After this siege thought an Imperialist victory, Tilly retreated. He failed to capitalize on his victory.[79] Seeing this, the king continued with his plan toward Frankfurt. However, before advancing towards Frankfurt he was informed that the Imperialists had sent a detachment of the force that had been left at Landsberg towards Anklam. They had taken this place.[79] In spite of this, the king ignored it, this would have been considered a very bold manoeuvre at the time, but despite the fact that the king had a force that could easily operate on his lines of communication, he continued his advance south.[79] Moving from Schwedt[80] the king moved his force south towards Frankfurt along the Oder.[80]

Arriving in front of Frankfurt on 3 April 1631,[80] a breach was made, and from this breach the city was taken.[80] This battle was a solid victory for the Protestant cause. On the fifth the king continued his advance.[81] He marched towards Landsberg after driving Imperialist cavalry attachments which were placed in the country surrounding Landsberg.[81]

On the 15th, the king positioned his army outside of Landsberg.[81] Banér, with five regiments,[81] set out from Frankfurt, who had been stationed there, to join him in the siege of Landsberg.[82] The siege was begun the same day. There was situated outside of Landsberg a strongly entrenched fortress, and it was clear to the king that if he wanted to acquire the city, he must first take this fortress. He had cannons brought up and fired upon the fortress. After a minimal exchange of artillery fire and the repulse of a sortie, the king stiffly offered terms to Landsberg. The next day the terms were accepted and the 4,000 Imperialist soldiers abandoned the city and fortress promising not to serve in the war for the next eight months.[82]

Diplomatic difficulties and the fall of Magdeburg

[edit]With the recent string of victories, the left flank (eastern flank) of the army was secure. There were two courses of action available to the king at this time; The first, was to march through Silesia[83] which would lead him through the lands attached to the Bohemian crown (a crown which Ferdinand held) directly to Vienna and bring the Habsburgs and the Catholics to terms by compelling them to sign a treaty after occupying Vienna. Despite the advantages of this scenario, for whatever reason the king deemed it to not be the best course of action.

The second course was to march to Magdeburg and relieve the siege taking place there and unite with his real and potential allies in Mecklenburg.[83] Despite the king's inclination, he had promised aid to the besieged city. At the present however, all he had done was send an able officer to oversee the construction of the defensive fortifications, train the local militia and oversee the defense itself once the siege commenced.

However, despite the fact that it was clear to the king what he wanted to do, it was to prove to be more difficult to bring about. If the king had not yet fully grasped the recalcitrance and distrust that existed among the Protestant German powers towards himself, then he would develop a proper appreciation of the situation in short order. After the taking of Landsberg and Frankfurt, the king, anticipating that Tilly would advance towards these places from Neuruppin via Küstrin, ordered that the bridge that which was situated in Küstrin (which would allow armies to march over the Oder) be destroyed. Küstrin was a part of the Electorate of Brandenburg, and the Prince-Elector of Brandenburg, George William – the king's own brother in law – felt that his neutrality had been violated and proved difficult to deal with because of this. In addition to his sister being the Queen of Sweden, George William was the vassal of Gustavus' cousin and most inveterate foe, Sigismund III Vasa, in his capacity as duke of the Duchy of Prussia. George William's father had paid homage to Sigismund, and he would later do fealty to his son. An illustration of the complicated international relations that typified the period, which were further complicated by the personal relationships of the rulers themselves.

The king wanted to set up his base of operations at the Spandau Citadel near Berlin for the campaign that would lead him to the Elbe.[84] This place was also within the realm of George William. The king met with George William and expressed his wish to get both Küstrin and Spandau into his possession. George William denied the request – despite their relations and common cause. After attempting to deal diplomatically with George William's vacillation, he finally informed him that if these places were not handed over to him voluntarily, he would take them with force.[84] Arrangements were then made by George William, who felt himself to be diplomatically isolated from both Saxony and the Habsburgs, to surrender the two places.[84] Even after the king began his advance towards Magdeburg, George William, proving recreant to his trust, did not surrender complete control of Spandau to the Swedish.

In addition, Pomerania was not meeting the quota of men and resources that it had promised to the Swedes. The money that was supposed to be delivered to the king for the conduct of the war, both from Sweden itself as well as the powers that had promised financial aid, were not coming in on time.[84] Also, the army had been hard pressed by the previous winter, particularly the cavalry, which had been pushed to the limit. The cavalry of the Swedish force on the whole was not on par with the Imperialists because of this. Conditions had become so bad that the men had started to engage in looting and banditry, which the king addressed by punishing the perpetrators of these actions.