1973 oil crisis: Difference between revisions

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

Nevertheless, the 1973 oil shock provided dramatic evidence of the potential power of developing world resource suppliers in dealing with the developed world. The vast reserves of the leading Middle East producers guaranteed the region its strategic importance, but the politics of oil still proves dangerous for all concerned to this day.. |

Nevertheless, the 1973 oil shock provided dramatic evidence of the potential power of developing world resource suppliers in dealing with the developed world. The vast reserves of the leading Middle East producers guaranteed the region its strategic importance, but the politics of oil still proves dangerous for all concerned to this day.. |

||

In thirty-year-old [[British government]] documents released in January 2004, it was revealed that the United States considered invading [[Saudi Arabia]] and [[Kuwait]] during the |

In thirty-year-old [[British government]] documents released in January 2004, it was revealed that the United States considered invading [[Saudi Arabia]] and [[Kuwait]] during the economic war and seizing the oil fields in those countries. According to the [[BBC]], other possibilities, such as the replacement of Arab rulers by "more amenable" leaders, or a show of force by "[[gunboat diplomacy]]," were officially rejected as untenable. <ref>See the [[January 2]] [[2004]] article by BBC News Online world affairs correspondent Paul Reynolds "US ready to seize Gulf oil in 1973" at [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/3333995.stm].</ref> |

||

==Notes and references== |

==Notes and references== |

||

Revision as of 03:46, 9 January 2007

The 1973 oil crisis first began on October 17, 1973 when the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), consisting of the Arab members of Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries(OPEC) plus Egypt and Syria, announced as a result of the ongoing Yom Kippur War, that they would no longer ship petroleum to nations that had supported Israel in its conflict with Syria and Egypt. This included the United States and its allies in Western Europe.

About the same time, OPEC members agreed to use their leverage over the world price-setting mechanism for oil in order to quadruple world oil prices, after attempts at negotiation with the "Seven Sisters" earlier in the month failed. Due to the dependence of the industrialized world on OPEC oil, these price increases were dramatically inflationary to the economies of the targeted countries, while at the same time suppressive of economic activity. The targeted countries responded with a wide variety of new, and mostly permanent, initiatives to contain their further dependency.[1]

The devaluation resulted in increased world economic and political uncertainty. Concurrently, in the early 1970s, the fall in the U.S. dollar went along with a rise in the price of oil (in USD). This improved the situation of U.S. industrialists in relation to European and Japanese competition. But the de-valorization — and then devaluation — of the dollar crystallized the unease of raw materials producers in the Third World; they saw the wealth under their lands being reduced and their assets growing in a currency that was worth significantly less than it had been recently. This set the stage for the struggle for control of the world's natural resources and for a more favorable sharing of the value of these resources between the rich countries and the oil-exporting nations of OPEC [citation needed].

OPEC devised a strategy of counter-penetration, whereby it hoped to make industrial economies that relied heavily on oil imports vulnerable to Third World pressures [citation needed]. Dwindling foreign aid from the U.S. and its allies, combined with the West's pro-Israeli stance in the Middle East, angered the Arab nations in OPEC.

Founding of OPEC

OPEC consisted of thirteen nations, including seven Arab countries, Iran, and also other major petroleum-exporting countries in the developing world like Venezuela. It had been officially announced on September 14 in Cairo, 1960 to protest pressure by major oil companies (mostly owned by U.S., British, and Dutch nationals) to reduce oil prices and payments to producers. At first it had operated as an informal bargaining unit for the sale of oil by Third World nations. It confined its activities to gaining a larger share of the revenues produced by Western oil companies and greater control over the levels of production. However, in the early 1970s it began to display its strength.

The Yom Kippur War

As mentioned, the Arab-Israeli conflict triggered a crisis already in the making. The West could not continue to increase its energy use 5% annually, pay low oil prices, yet sell inflation-priced goods to the petroleum producers in the Third World. This was stressed by the Shah of Iran, whose nation was the world's second-largest exporter of oil and the closest ally of the United States in the Middle East at the time. "Of course [the world price of oil] is going to rise," the Shah told the New York Times in 1973. "Certainly! And how...; You [Western nations] increased the price of wheat you sell us by 300%, and the same for sugar and cement...; You buy our crude oil and sell it back to us, redefined as petrochemicals, at a hundred times the price you've paid to us...; It's only fair that, from now on, you should pay more for oil. Let's say ten times more."[2]

Arab oil embargo

On October 16 1973, as part of the political strategy that included the Yom Kippur War, OAPEC cut production of oil and placed an embargo on shipments of crude oil to the West, with the United States and the Netherlands specifically targeted. Also imposed was a boycott of Israel. Since oil demand is very price inelastic, (i.e., the quantity purchased falls little with price rises), prices had to rise dramatically to reduce demand to the new, lower level of supply. The embargo on oil caused the market price for oil to rise substantially. Government price controls, designed to maintain oil affordability, exacerbated the economic impact by creating shortages. High prices from the embargo were exacerbated by the shortages caused by the price controls, resulting in a series of recessions and high inflation that persisted until the early 1980's.

The graph to the right is based on the nominal -- not real -- price of oil, and so overstates prices of more recent years. However, the effects of the Arab Oil Embargo are clear: it effectively doubled the real price of crude oil at the refinery level. and caused massive shortages in the US. This exacerbated a recession that had already begun, and led to a global recession through the rest of 1974.

Over the long term, the oil embargo changed the nature of policy in the West toward more exploration and energy conservation. Changes also included a more restrictive monetary policy that was better at fighting inflation.

Chronology

- August 23 1973 - In preparation for the Yom Kippur War, Saudi King Faisal and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat meet in Riyadh and secretly negotiate an accord whereby the Arabs will use the "oil weapon" as part of the upcoming military conflict.

- 15 September 1973 - The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) declares a negotiating front, consisting of the 6 Persian Gulf States, to pressure for price increases and an end to support of Israel, based on the 1971 Tehran agreement.

- 6 October - Egypt and Syria attack Israel on Yom Kippur, starting the fourth Arab-Israeli War, the Yom Kippur War.

- 8 October–10 - OPEC negotiations with oil companies to revise the 1971 Tehran price agreement fail.

- 16 October - Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Qatar unilaterally raise posted prices by 17% to $3.65 a barrel and announce production cuts.

- 23 October–28 - The Arab oil embargo is extended to the Netherlands.

- 5 November - Arab producers announce a 25% output cut. A further five percent cut is threatened.

- 23 November - The Arab embargo is extended to Portugal, Rhodesia, and South Africa.

- 27 November - U.S. President Richard Nixon signs the Emergency Petroleum Allocation Act authorizing price, production, allocation and marketing controls.

- 9 December - Arab oil ministers agree a further five percent cut for non-friendly countries for January 1974.

- 25 December - Arab oil ministers cancel the five percent output cut for January. Saudi oil minister Yamani promises a 10% OPEC production rise.

- 7 January–9, 1974 - OPEC decides to freeze prices until April 1.

- 11 February - U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger unveils the Project Independence plan to make U.S. energy independent.

- 12 February–14 - Progress in Arab-Israeli disengagement brings discussion of oil strategy among the heads of state of Algeria, Egypt, Syria and Saudi Arabia.

- 17 March - Arab oil ministers, with the exception of Libya, announce the end of the embargo against the United States.

Immediate economic impact of the embargo

The effects of the embargo were immediate. OPEC forced the oil companies to increase payments drastically. The price of oil quadrupled by 1974 to nearly US$12 per US gallon barrel (75 US$/m³). [2]

This increase in the price of oil had a dramatic effect on oil exporting nations, for the countries of the Middle East who had long been dominated by the industrial powers were seen to have acquired control of a vital commodity. The traditional flow of capital reversed as the oil exporting nations accumulated vast wealth. Some of the income was dispensed in the form of aid to other underdeveloped nations whose economies had been caught between higher prices of oil and lower prices for their own export commodities and raw materials amid shrinking Western demand for their goods. Much of it, however, fell into the hands of elites who reinvested it in the West or enhanced their own well-being. Much was absorbed in massive arms purchases that exacerbated political tensions, particularly in the Middle East.

OPEC-member states in the developing world withheld the prospect of nationalization of the companies' holdings in their countries. Most notably, the Saudis acquired operating control of Aramco, fully nationalizing it in 1980 under the leadership of Ahmed Zaki Yamani. As other OPEC nations followed suit, the cartel's income soared. Saudi Arabia, awash with profits, undertook a series of ambitious five-year development plans, of which the most ambitious, begun in 1980, called for the expenditure of $250 billion. Other cartel members also undertook major economic development programs.

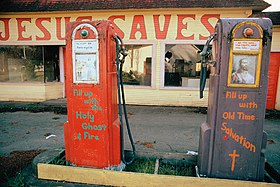

Meanwhile, the shock produced chaos in the West. In the United States, the retail price of a gallon of gasoline rose from a national average of 38.5 cents in May 1973 to 55.1 cents in June 1974. Meanwhile, New York Stock Exchange shares lost $97 billion in value in six weeks.

With the onset of the embargo, U.S. imports of oil from the Arab countries dropped from 1.2 million barrels (190,000 m³) a day to a mere 19,000 barrels (3,000 m³). Daily consumption dropped by 6.1% from September to February, 7% by the summer of 1974. During that period, the United States suffered its first fuel shortage since World War II[citation needed].

Underscoring the interdependence of the world societies and economies, oil-importing nations in the noncommunist industrial world saw sudden inflation and economic recession. In the industrialized countries, especially the United States, the crisis was for the most part borne by the unemployed, the marginalized social groups, certain categories of aging workers, and increasingly, by younger workers. Schools and offices in the U.S. often closed down to save on heating oil; and factories cut production and laid off workers. In France, the oil crisis spelt the end of the Trente Glorieuses, 30 years of very high economic growth, and announced the ensuing decades of permanent unemployment.

The embargo was not uniform across Europe. Of the nine members of the European Economic Community, the Dutch faced a complete embargo (having voiced support for and supplied arms to Israel and allowed the Americans to use Dutch airfields for supply runs to Israel), the United Kingdom and France received almost uninterrupted supplies (having refused to allow the U.S. to use their airfields and embargoed arms and supplies to both the Arabs and the Israelis), whilst the other six faced only partial cutbacks. The UK had traditionally been an ally of Israel, and Harold Wilson's government had supported the Israelis during the Six Day War, but his successor, Ted Heath, had reversed this policy in 1970, calling for Israel to withdraw to its pre-1967 borders. The members of the EEC had been unable to achieve a common policy during the first month of the Yom Kippur War. The Community finally issued a statement on 6 November, after the embargo and price rises had begun; widely seen as pro-Arab, this statement supported the Franco-British line on the war and OPEC duly lifted its embargo from all members of the EEC. The price rises had a much greater impact in Europe than the embargo, particularly in the UK (where they combined with industrial action by coal miners to cause an energy crisis over the winter of 1973-74, a major factor in the breakdown of the post-war consensus and ultimately the rise of Thatcherism).

Unlike any other oil-importing developed nation, Japan fared particularly well in the aftermath of the world energy crisis of the 1970s. Japanese automakers led the way in an ensuing revolution in car manufacturing. The large automobiles of the 1950s and 1960s were replaced by far more compact and energy efficient models. (Japan, moreover, had cities with a relatively high population density and a relatively high level of transit ridership.) Japanese automakers would later establish their overseas facilities in the United States during the 1980s (e.g. Nissan having its manufacturing facility in Smyrna, Tennessee) to which Detroit's Big Three (GM, Ford, Chrysler) were making the transition from large automobiles to smaller cars. The market once dominated by large automobiles was replaced by the truck/van conversions - trucks/vans were not affected by the CAFE regulations and DOT mandates.

A few months later, the crisis eased. The embargo was lifted in March 1974 after negotiations at the Washington Oil Summit, but the effects of the energy crisis lingered on throughout the 1970s. The price of energy continued increasing in the following year, amid the weakening competitive position of the dollar in world markets; and no single factor did more to produce the soaring price inflation of the 1970s in the United States.

Price controls and rationing

The crisis was further exacerbated by government price controls in the United States, which limited the price of "old oil" (that already discovered) while allowing newly discovered oil to be sold at a higher price, resulting in a withdrawal of old oil from the market and artificial scarcity. The rule had been intended to promote oil exploration. This scarcity was dealt with by rationing of gasoline (which occurred in many countries), with motorists facing long lines at gas stations.

In the U.S., drivers of vehicles with license plates having an odd number as the last digit were allowed to purchase gasoline for their cars only on odd-numbered days of the month, while drivers of vehicles with even-numbered license plates were allowed to purchase fuel only on even-numbered days. The rule did not apply on the 31st day of those months containing 31 days, or on February 29 in leap years — the latter never came into play, as the restrictions had been abolished by 1976.

Conservation and reduction in demand

The U.S. government response to the embargo was quick but of limited effectiveness. To conserve gasoline, the National Maximum Speed Law imposed a nationwide 55 mph (89 km/h) speed limit which ended up lasting 13 years, for reasons mostly unrelated to the oil crisis. President Nixon named William Simon as an official "energy czar," and in 1977, a cabinet-level Department of Energy was created, leading to the creation of the United States's Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

Year-round Daylight Saving Time was implemented: at 2:00 a.m. local time on January 6, 1974, clocks were advanced one hour across the nation. The move spawned significant criticism because it forced many children to commute to school before sunrise. As a result, the clocks were turned back on the last Sunday in October as originally scheduled, and in 1975 clocks were set forward one hour at 2:00 a..m. on February 23, the later date being adopted to address the aforementioned issue. The pre-existing daylight-saving rules, calling for the clocks to be advanced one hour on the last Sunday in April, were restored in 1976.

The crisis also prompted a call for individuals and businesses to conserve energy — most notably a campaign by the Advertising Council using the tag line "Don't Be Fuelish." Many newspapers carried full-page advertisements that featured cut-outs which could be attached to light switches emblazoned with the slogan "Last Out, Lights Out: Don't Be Fuelish".

The U.S. "Big Three" automakers' first order of business after Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards were enacted was to downsize existing automobile categories. By the end of the 1970s, 121-inch wheelbase vehicles were a thing of the past. Before the mass production of automatic overdrive transmissions and electronic fuel injection, the traditional FR (front engine/rear wheel drive) layout was being phased out for the more efficient and/or integrated FF (front engine/front wheel drive), starting with compact cars. Using the Volkswagen Rabbit as the archetype, much of Detroit went FF after 1980 in response to CAFE's 27.5 MPG mandate. Vehicles such as the Ford Fairmont were short-lived in the early 1980s.

Downsizing automobiles might have been considered profitable; however, the smaller size affected safety regulations. Some consider the product liability cases against the Ford Pinto during the late 1970s the result of automakers failing to take user safety into consideration. As full-sized vehicles were being phased out and/or downsized, light truck/van conversions (which later evolved into modern-day sport utility and crossover vehicles) were deemed as viable replacements.

Search for alternatives

The energy crisis led to greater interest in renewable energy, especially wood fuel and spurred research in solar power and wind power. It also led to greater pressure to exploit North American oil sources, and increased the West's dependence on coal and nuclear power.

In Australia, heating oil ceased being considered an appropriate winter heating fuel. This often meant that a lot of oil-fired room heaters that were popular from the late-1950s to the early-1970s were considered outdated. It also meant that some enterprising individuals designed aftermarket gas-conversion kits that let these heaters burn natural gas or propane.

But the initial moves toward more efficient automobiles and alternative sources of energy stalled as oil prices fell and memories of gasoline shortages of 1973 faded.

For the handful of industrialized nations that were net energy exporters the effects of the oil crisis were very different. In Canada the industrial east suffered many of the same problems of the United States. In oil rich Alberta there was a sudden and massive influx of money that quickly made it the richest province in the country. The federal government attempted to correct this imbalance through the creation of the government-owned Petro-Canada and later the National Energy Program. These efforts produced a great deal of anger in the west producing a sentiment of alienation that has remained a central element of Canadian politics to this day. Overall the oil embargo had a sharply negative effect on the Canadian economy. The economic malaise in the United States easily crossed the border and increases in unemployment and stagflation hit Canada as hard as the United States despite Canadian fuel reserves.

The Soviet Union was also a net oil exporter and the increase in the price of oil had an immediate effect on that country. The Soviet economy had stagnated for several years and the increase in the price of oil had a beneficial effect, especially after the bloc's internal terms of trade were adjusted to reflect the increased value of Russian oil. The increase in foreign currency reserves allowed the import of grain and other foodstuffs from abroad, increased production of consumer goods and the ability to keep military spending at its traditional levels. Some historians believe the windfall in oil revenues during this period kept the Soviet Union in existence for a considerably longer period of time than would otherwise have occurred. When in 1991 the Soviet Union was disbanded, the price of oil was at a level of just 12 dollars per barrel.

Macroeconomic effects

The 1973 oil crisis was a major factor in Japan's economy shifting away from oil-intensive industries and resulted in huge Japanese investments in industries like electronics.[citation needed]

The Western nations' central banks sharply cut interest rates to encourage growth, deciding that inflation was a secondary concern. Although this was the orthodox macroeconomic prescription at the time, the resulting stagflation surprised economists and central bankers, and the policy is now considered by some to have deepened and lengthened the adverse effects of the embargo.[citation needed]

Long-term effects of the embargo are still being felt. Public suspicion of the oil companies, who were thought to be profiteering or even working in collusion with OAPEC, continues unabated (seven of the fifteen top Fortune 500 companies in 1974 were oil companies, with total assets of over $100 billion).[citation needed]

Effects on international relations

The Cold War policies of the Nixon administration also suffered a major blow in the aftermath of the oil embargo. They had focused on China and the Soviet Union, but the latent challenge to U.S. hegemony coming from the Third World was now starkly evident. U.S. power was under attack even in Latin America.

The oil embargo was announced roughly just one month after a right-wing military coup in Chile toppled elected socialist president Salvador Allende on September 11, 1973. The U.S.'s subsequent assistance to this government did little in the short-run to curb the activities of socialist guerrillas in the region. The response of the Nixon administration was to propose doubling of the amount of military arms sold by the United States. As a consequence, a Latin American bloc was organized and financed in part by Venezuela and its oil revenues, which quadrupled between 1970 and 1975.

In addition, Western Europe and Japan began switching from pro-Israel to more pro-Arab policies (some of which are still in effect today). This change further strained the Western alliance system, for the United States, which imported only 12% of its oil from the Middle East (compared with 80% for the Europeans and over 90% for Japan), remained staunchly committed to its backing of Israel.

A year after the unveiling of the 1973 oil embargo, the nonaligned bloc in the United Nations passed a resolution demanding the creation of a "new international economic order" in which resources, trade, and markets would be distributed more equitably, with the local populations of nations within the global South receiving a greater share of benefits derived from the exploitation of southern resources, and greater respect for the right to self-directed development in the South be afforded by the North.

Decline of OPEC

Since 1973, OPEC failed to hold on to its preeminent position, and by 1981, its production was surpassed by that of other countries. Additionally, its own member nations were divided among themselves. Saudi Arabia, trying to gain back market share, increased production and caused downward pressure on prices, making high-cost oil production facilities less profitable or even unprofitable. The world price of oil, which had reached a peak in 1979, at more than US$80 a barrel (503 US$/m³) in 2004 dollars, decreased during the early 1980s to US$38 a barrel (239 US$/m³). In real prices, oil briefly fell back to pre-1973 levels. Overall, the reduction in price was a windfall for the oil-consuming nations: United States, Japan, Europe and especially the Third World.

Part of the decline in prices and economic and geopolitical power of OPEC comes from the move away from oil consumption to alternate energy sources. OPEC had relied on the famously limited price sensitivity of oil demand to maintain high consumption, but had underestimated the extent to which other sources of supply would become profitable as the price increased. Electricity generation from nuclear power and natural gas, home heating from natural gas and ethanol blended gasoline all reduced the demand for oil.

At the same time, the drop in prices represented a serious problem for oil-producing countries in Northern Europe and the Persian Gulf region. For a handful of heavily populated, impoverished countries, whose economies were largely dependent on oil — including Mexico, Nigeria, Algeria, and Libya — governments and business leaders failed to prepare for a market reversal, the price drop placed them in wrenching, sometimes desperate situations.

When reduced demand and over-production produced a glut on the world market in the mid-1980s, oil prices plummeted and the cartel lost its unity. Oil exporters such as Mexico, Nigeria, and Venezuela, whose economies had expanded frantically, were plunged into near-bankruptcy, and even Saudi Arabian economic power was significantly weakened. The divisions within OPEC made subsequent concerted action more difficult.

Nevertheless, the 1973 oil shock provided dramatic evidence of the potential power of developing world resource suppliers in dealing with the developed world. The vast reserves of the leading Middle East producers guaranteed the region its strategic importance, but the politics of oil still proves dangerous for all concerned to this day..

In thirty-year-old British government documents released in January 2004, it was revealed that the United States considered invading Saudi Arabia and Kuwait during the economic war and seizing the oil fields in those countries. According to the BBC, other possibilities, such as the replacement of Arab rulers by "more amenable" leaders, or a show of force by "gunboat diplomacy," were officially rejected as untenable. [3]

Notes and references

- ^ See, e.g., Alan S. Blinder, Economic Policy and the Great Stagflation (New York: Academic Press, 1979); Otto Eckstein, The Great Recession (Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1979); Mark E. Rupert and David P. Rapkin, "The Erosion of U.S. Leadership Capabilities," in Paul M. Johnson and William R. Thompson, eds., Rhythms in Politics and Economics (New York: Praeger, 1985)

- ^ Quoted in Walter LaFeber, Russia, America, and the Cold War (New York, 2002), p. 292.

- ^ See the January 2 2004 article by BBC News Online world affairs correspondent Paul Reynolds "US ready to seize Gulf oil in 1973" at [1].

See also

- Energy conservation

- Energy crisis

- Supply shock

- 1979 energy crisis

- 1990 spike in the price of oil

- Oil price increases of 2004-2006

- Hubbert peak theory

- Boycott

- Embargo

External links

- Kissinger's Yom Kippur oil shock- Article that claims that the 1973 energy crisis was orchestrated by the U.S.

- Global Oil Crisis Updates and Energy Information Resources

- Saudi dove in the oil slick - Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani, former oil minister of Saudi Arabia gives his personal account of the 1973 energy crisis.