Southgate–Lewis House

The Southgate–Lewis House is located one mile east of the Texas State Capital in Austin, Texas at 1501 East 12th Street. The house was constructed in 1888 and now stands as an African-American Historical Landmark and as a repository for African-American History and Culture in a region of east Austin, which historically became an African-American neighborhood.

The Southgate-Lewis House was constructed by the renowned builder Robert C. Lambie in 1888 as the residence for the publisher and bookbinder John Southgate, whose business was located on Congress Avenue, next door to the Lundberg Bakery. Few residences of its period, scale, and complexity remain in this location where more simple vernacular buildings are the rule and high-style structures, such as the Southgate–Lewis House, are the rare exception. This large two-story wooden frame structure is a richly-textured and finely-restored late Victorian house in the Stick Style.

The Charles M Lewis family owned the house from 1913 to 1979 and during this period the Lewis family brought to the house a rich and treasured historical legacy. Following the death of Marguerite Mae Dee Lewis in 1970, the house was abandoned for nearly a decade. The house fell into decline and, because it became a danger to the community, the house was scheduled for demolition. Fortunately, the house was saved one week before demolition. The house was then restored and preserved.

The Southgate-Lewis House is now a city, state, and national historic landmark. In 1986 the house was presented to the W.H. Passon Historical Society,[1] as a gift, by a professor at The University of Texas at Austin.[2] The objective of the W.H. Passon Historical Society is to secure and preserve materials and artifacts related to Black culture in Austin and Travis County.

Landmark status designation and recognition

- 1979 – Designated a City of Austin landmark[3]

- 1980 – Awarded the Heritage Society of Austin Historic Preservation Award[4][5]

- 1985 – Designated a landmark by the National Register of Historic Places[6][7]

- 1987 – Recognized by the State of Texas 70th Legislature, Resolution No. 141, for ensuring the legacy of Black heritage in Austin[8]

- 1987 – Awarded the "Helping Hands Award for Community Service" by the Texas Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History[9]

- 1988 – Designated a Recorded Texas Historic Landmark[10][11]

Southgate–Lewis House | |

Southgate-Lewis House in June 2021. | |

| Location | 1501 East 12th Street Austin, Texas, USA |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 30°16′23″N 97°43′25″W / 30.27306°N 97.72361°W |

| Area | East Austin |

| Built | 1888 |

| Architect | R. C. Lambie |

| Architectural style | Gothic, Victorian, Stick, Eastlake |

| NRHP reference No. | 85002265[12] |

| RTHL No. | 15230 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 17, 1985 |

| Designated RTHL | 1988 |

Gallery

Photographs Directly After Historic Restoration

Shown above are photographic images of the house (which was constructed by R.C. Lambie in 1888) just after the historic restoration in 1980 was completed: (a) the west elevation, (b) the renowned balustrade of the staircase in the main foyer on the first floor, and (c) the north elevation of the front of the house.

Stick Style High Victorian Gothic Revival House

The photographs shown in (a) & (c) illustrate many of the characteristics of the Stick Style High Victorian Gothic Revival house.[15] The Old-House Journal provides a succint and apt description: "Stick-style houses generally exhibit a strong vertical emphasis, with tall windows, multiple stories, and surface ornament reaching skyward along with sharply pitched roofs. . . . The defining feature of these houses, however, is stickwork: expressive wood facing and ornament that evokes the grids and angles of structural framing in their layout. In Stick houses, the exterior clapboards and shingles are divided into panels by vertical and horizontal boards, bringing the symbolism, if not the actual position, of the underlying posts and joists to the façade."[16] It is worth noting that the Southgate-Lewis House has yet to be painted in a fashion that would emphasize the Stick Style to its fullest extent.

Note the strong vertical emphasis; the high pitched ("Gothic Arch") gable roof with an extended overhang; the multiple stories; the bay window; the tall narrow double-hung windows; the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal "stick-work" that segregates, accentuates, and helps define (or "echo") structural elements; the overhanging eves with exposed rafter ends; the diagonal braces supporting the overhanging eves; the crossed bargeboard trim; and the dormer with ornamental qualities that evoke the Eastlake Movement.

Woodwork Varnish

Note that the color of the balustrade staircase woodwork shown in photograph (b), directly after the restoration in 1980, was a light reddish brown. However, the color of the balustrade staircase woodwork is quite different in the 2021 photograph (shown herein). One can only speculate that the woodwork has been stained a darker color sometime during the intervening four decades, for reasons unknown.

Architecture

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places describes the Architectural Style as "High Victorian" Gothic Revival. It might also be referred to as Carpentered Gothic. The house has projecting eaves and gables and a prominent, front bay with a dentilated cornice. Siding and trim are unusually ornate and varied.[17] A continuous band of vertical siding at the base of the structure is capped with a horizontal band at the window sill. Drop siding occurs up to the sills of the second story windows, above which multiple rows of fish-scale and rectangular shingles alternate. Ornamental bargeboard trim with brackets is located at the eave line, and the roof is wood shingle. Two brick chimneys rise far above the cedar shake roof. A dormer on the west elevation has diagonal support brackets for the extended overhang and crossed bargeboard trim.[18] There are 22 double hung floor to ceiling windows.

Stick Style Victorian Architecture

Given the general classification of Victorian Architecture,[19][20] the house is best described within the domain of the Stick Style[21][15] (and perhaps, to some extent, the house can be described within the domain of the more highly stylized Eastlake Movement[22][23]). It is said that the Stick Style architecture "represented the most innovative design concepts and building technologies of its time,"[16] The Stick Style was a late 19th century American architectural style (circa 1860-1900) that featured steeply pitched gabled roofs, overhanging eaves with exposed rafter ends and diagonal support braces. On the elevations, ornamental vertical and horizontal ("stick-work") bands are raised from the wall; these bands separate levels and they evoke the grids of the structural framing. The wooden walls are clad with boards and/or decorative shingles. The exterior boards and shingles are separated and defined by vertical and horizontal stick-work; again, the stick-work evokes the underlying carpentered framework. Windows are generally one-over-one, double-hung, and they are frequently paired. The Stick style homes exhibit a strong vertical emphasis, with tall windows, multiple stories, and skyward pointing sharply pitched roofs.[24][25]

Newel Posts of Stairway Balustrade

The newel posts that support the staircase balustrade in the main entry hall are particularly worthy of note. The posts are firmly embedded within the structural framework (and they do not wiggle). They are not only stout, strong, and elegantly beautiful, they also contain detailed engravings. For reasons that remain unknown, one of these engravings shows what appears to be a replica of a man's head in profile that could be found in one of the Assyrian sculptural reliefs from the first millennium BC art of Mesopotamia.[26] A second newel post contains a similar engraving; however, this time the engraving depicts a woman – again, most probably from the same historical period. Other newel post engravings depict abstract geometrical forms; one such evokes the image of a daisy. Note the finials that project upward on the tops of the newel posts. These serve both form and function in that they are fine looking ornaments that can be used with a hand as one begins to mount the staircase and as one rounds the right angle turns at each flight of stairs. Note also the downward pointing finial (a pendant) that projects into the main foyer. Here the pendant finial is simply pleasing to the eye.

Woodturning Artistry

The artistry and the craftsmanship of woodturning (an ancient craft) is brilliantly displayed in the main hallway staircase balustrade of the Southgate-Lewis home.[27][28][29] Each baluster within the balustrade is, in itself, a work of art that was uniquely formed at the hands of a very skilled craftsman. The balusters were most definitely not made by a machine; but instead they were made by hand, one by one. Although the balusters all look identical as one ascends or descends the beautiful staircase, careful inspection reveals that each baluster is obviously unique. A moments careful inspection of two adjacent balusters soon reveals, to the untrained eye, that although they are nearly identical, they are indeed individually unique.

Interior Floor Plan

The first floor interior of the house is composed of five rooms. From the front door one enters the main entry hall, which contains the stairway balustrade that leads to the second floor. From the foyer one can enter the main parlour via a door on the right. The parlour contains a fireplace (and functional chimney), with a mantel and brightly colored tiles arranged in a complex non-repeating geometrical pattern. A pair of very large wooden double doors (that slide into pockets) separate the first parlour from the second parluor. The second parlour has one door which leads to a wrap-around exterior covered porch and another door that leads to a formal dining room. The dining room is completely lined with tongue and groove beaded boards (ceiling and walls) with a wainscoting that wraps around all four walls (see photograph). The dining room then leads to a small kitchen. The kitchen has a door that opens to the wrap-around exterior covered porch. The ceilings in all of the rooms are very high. The staircase in the main entry hall leads upstairs to the second floor, which is composed of three generously sized bedrooms, a small closet, a small bathroom, and a large hallway, with a balustrade surrounding the stairwell. From the generous hallway, a large floor to ceiling window opens onto a small exterior balcony.

History

Robertson Hill

Joseph William Robertson (1809-1870) is the patriarch of the family after whom Robertson Hill was named.[30][31] Robertson was a physician, a Texas Ranger, and a member of the House of Representatives in the Fourth Congress of the Republic of Texas. He established a pharmaceutical business and a medical practice on Congress Avenue. He was elected mayor of Austin in 1843. Robertson is buried in Oakwood Cemetery, two blocks from the Southgate-Lewis House. In 1848, Robertson purchased a large tract of land from Dubois de Saligny one half mile east of the city center (which included a home that is now known as The French Legation[32]). Robertson and his son, George L. Robertson, began actively subdividing the family property and selling lots. This region (which includes the Southgate-Lewis House) became known as Robertson Hill.[33]

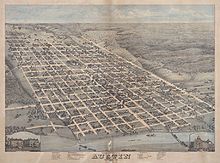

College Street in 1873

The "Bird's Eye View of the City of Austin," shown herein, was created by Augustus Koch in 1873. The map provides an interesting historical perspective for our modern day consideration of the Southgate-Lewis House, on many different levels of analysis. The Southgate-Lewis House was constructed only 15 years after this map was created. In 1888 the population of Austin was somewhere between 10 to 15 thousand people.[34] In comparison, the population of San Francisco at that time, where comparable houses were quite common, was a little under 300,000. In many respects, it is somewhat difficult to imagine a building of this complexity being constructed on the "outskirts" of the small town (in what appears to be a forested wilderness) depicted within this "Bird's Eye View."

Judging from this old map, Congress Avenue and College Street were the main streets of Austin; both streets converge upon (or radiate out from) what was the center of the city at that point in time – namely, the State Capitol Building. College Street was a large street (a main street) leading directly from the center of the State Capital Building up into the Robertson Hill area, where homes were being constructed. The only comparable street heading east is the street near Cherry Street, which to this day leads up the hill into the Oakwood Cemetery. The point is: This "Bird's Eye View" reveals that College Street was a main street. The Southgate-Lewis House was constructed on this main street.

Street Names Change

On September 21, 1886, the street names in Austin were changed to numbers and College Street became 12th Street. Further, Congress Avenue was designated as the dividing line for naming the numbered streets East vs West. The Southgate-Lewis House is located at 1501 East 12th Street.

John Southgate

John Southgate was a bookbinder and publisher in Austin, Texas[35][36] with a business at 1008 Congress Avenue, right next door to Charles Lundberg's Bakery at 1006 Congress Avenue, only a few steps away from the Texas State Capital building. Southgate had more than thirty years of experience working in both England as well as in the United States, in establishments such as Daniel Appleton & Company (a firm which was founded in 1825 and whose successor lives on as Appleton-Century-Crofts). In the late 1800s the Austin American Statesman made numerous remarks praising the work of John Southgate. For example: "Mr. John Southgate has just completed an 850-page ledger, which is a beautiful specimen of the bookbinder's art. It is handsomely bound, and in finish and workmanship cannot be excelled any where [sic]" (April 12, 1988, Page 3); "The Statesman commends Mr. Southgate as an honest, faithful man, and one whose business engagements will be punctiliously complied with" (April 29, 1884, Page 4). Southgate eventually associated with the Eugene Von Boeckmann Publishing Company.[37]

Robert C. Lambie

Robert C. Lambie was contracted by John Southgate to build the home in 1888. Lambie (with his stonemason partner Francis Fischer) built many grand and beautiful historic structures in Texas, including: (a) the First Engineering Building at The University of Texas at Austin[38][39][40] (b) the historic home and studio of the iconoclastic German sculptor Elisabet Ney, now the Elisabet Ney Museum[41] (shown herein), (c) the Old Main Building[42] at Texas State University (shown herein), and (d) the Hays County Courthouse (shown herein).[43]

Lambie was famous for his elaborate woodwork, as evidenced by the balustrades, ornate door molding, window molding, finial pendants, and the beautifully elaborate plinth blocks within the Southgate–Lewis House. Quoting the State of Texas Legislature: "the Southgate-Lewis Home at the corner of East 12th and Comal Streets in Austin .... [contains] one of the finest staircases in all of Austin."[8]

Lewis Family Habitation

Charles M. Lewis and Marguerite Mae Dee Lewis

The Charles M. Lewis family owned the house from 1913 to 1970. Charles M. Lewis was a prominent Black citizen in Austin. Mr. Lewis was a professor at Samuel Huston College, and Marguerite Mae Dee Lewis (his daughter) was a teacher at L.C. Anderson High School,[44] which at the time was located only two blocks from the house.[45] The photograph of Mae Dee Lewis that hangs on the wall within the Southgate-Lewis House today is shown herein. The photograph caption reads as follows: "Mae D. Lewis, Spanish Teacher, OLCA High School, Class of 1957." The acronym OLCA stands for the following: "Old Laurine Cecil Anderson." Laurine Cecil Anderson was most famous for his teachings and being a school administrator in Texas; he founded the Colored Teachers State Association of Texas." Old Laurine Cecil Anderson High School was located only a few blocks from the Southgate-Lewis House.

Robertson Hill High School and Laurine Cecil Anderson

It is worth noting here (from the records of W.H. Passon) that prior to 1907 this school was entitled Robertson Hill High School. High School Classes for African-American students were initiated in Austin within the Robertson Hill High School in 1889.[46] In 1896 Laurine Cecil Anderson resigned his position at Prairie View to become principal of Austin's Robertson Hill High School. Then, in 1907 the school became E.H. Anderson High School and finally the school was renamed in honor of Lauren Cecil Anderson in 1938. Lauren Cecil Anderson was a neighbor and family friend of the DeBlanc family and he used to lend books to Ada Marie DeBlanc Simond.[14] Marguerite Mae Dee Lewis, the Lewis family as a whole, and their life during their time in the Southgate-Lewis House, have been immortalized in a series of children's books written by Ada Marie DeBlanc Simond (see below).

Saving the Condemned Southgate-Lewis House

Condemnation and Demolition

After the death of Ms. Lewis in 1970, the house was abandoned for nearly a decade and as a result the house fell into dramatic disrepair. A detailed description of the disrepair would only engender sorrow. Among other problems, most of the windows were broken and the roof was missing in many locations; thus water had been entering the house for some long time. An entire flock of pigeons had taken up residence in the house, bringing with them the obvious consequences. Stated summarily: It was vacant, it was rapidly deteriorating, and because it was a danger to the community, "it was a condemned building scheduled for demolition."[8]

Professor Discovers Condemned House

A professor had just moved to Austin after living in Berkeley California for his first thirty years. Having just completed his Ph.D. at the University of California in Berkeley, he had now become a new assistant professor at The University of Texas at Austin. The professor, Duane G. Albrecht,[47] was looking for a home and he noticed the abandoned dilapidated Victorian house (which is only a few blocks east from the university) one week before the scheduled demolition date,[8] in February of 1979. As noted above: The house was a danger to the community and "it was a condemned building scheduled for demolition."[8] (At this point in time, the house belonged to Mary Elizabeth Lovelady – for reasons unknown.)

Community Supports Restoration

The professor set out to save the house, to restore the house, and to make the house his home. He was aided by a grant from The Heritage Society of Austin[48] (now named Preservation Austin[49]). Elaine Mayo, the Executive Director of the Heritage Society was very supportive of the project. David Hoffman,[50] the well-established historic preservation architect with the firm Bell, Klein and Hoffman,[51] provided much needed advice. Charles Betts[52][53] extended his faith in the project and as a consequence Franklin Savings[54] provided the necessary loan. It is interesting to note that Charles Betts and Franklin Savings were located in a very grand historic Austin building – The Walter Tips Building on Congress Avenue,[55][56][57] a City, State, and National Landmark. A special type of loan was required during the period of the restoration work and this loan was arranged by Randy Peschel who was at City National Bank of Austin.

Restoration of The Southgate-Lewis House

Restoration Craftsman

Peter J. Fears was the craftsman in charge of the restoration work. Fears had just completed an exemplary restoration of the historic Limerick-Frazier House,[58][59][60] only a few blocks away on 13th Street. Fears moved into the restored home with his family. The Limerick-Frazier House, located at 810 East 13th Street, was constructed in 1876.

When Peter Fears began the restoration, he discovered a structural feature of the house that probably helped preserve the structural integrity of the house during its extended period of deterioration, particularly with all of the damage on the roof. Fears was happy to discover a somewhat surprising fact about the carpentered framing of the Southgate-Lewis House – all of the interior walls were reinforced with long and wide diagonal boards.

Interior Wall Diagonal Shiplap

As a consequence of the water damage, the original lovely wall paper in the condemned building was not salvageable. Instead, the wall paper had to be removed. Upon removal Fears discovered that the interior walls were not composed of the traditional "plaster upon lath," which was so common in the late 19th century Victorian houses. "Most houses built before 1940 have lath and plaster walls.[61] Lath is a thin flat strip of wood (comparable to balsa wood) that can be easily broken in half. The trellis-like lath provides almost no structural support for the carpentered framing of the house; however, the lath does provide an excellent foundation for the application of plaster.

What Fears discovered is that the walls were all lined with very thick, wide, and long lumber that is referred to as "shiplap."[62] The very long pieces of shiplap (with a "rabbet"[63] on opposite sides of each edge, that allows the boards to connect in a secure fashion) were applied diagonally, at an angle of 45 degrees relative to the carpentered framework. The shiplap provided an uncommon strength to the structural integrity of the house. The strongest gusts of wind (which are quite common in the region) applied to the very tall and expansive exterior walls of the house could not produce the slightest quiver or tremple within the house.

Calcasieu Lumber

Interestingly, the interior wall diagonal shiplap boards were proudly stamped with the name of the lumberyard of origin. That lumberyard was the newly established "Calcasieu Lumber Co." Calcasieu was founded in 1883, only a few years prior to the construction of the house. Calcasieu began downtown along the Colorado river between Guadalupe and Lavaca and grew to occupy six city blocks in the 1950s. Calcasieu Lumber Co lives on to this day.[64][65] The Calcasieu Lumber Co. was "named after the top-quality lumber that came from Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana"[66] – in particular, the longleaf pine.[67]

Unexpected Treasures

Treasures

The restoration work on the interior of the Southgate-Lewis House revealed many unexpected treasures: a beautiful elaborate staircase balustrade, beaded tongue-in-groove (tongue and groove) hardwood paneling, patterned brass hardware, wainscotting, fine wood floors with very long timbers quarter sawn from old-growth heartwood longleaf pine, from "The Calcasieu Pine District of Louisiana"[67] – supplied by the Calcasieu Lumber Co.[66][68]

Heartbreaks

There were some heartbreaks as well. For example, white paint had been applied to the beaded tongue and groove boards that composed the walls and ceiling of the formal dining room above the wainscotting – as opposed to clear translucent varnish of one sort or another that allows one to view the unique natural patterns of the natural wood. Instead of seeing the ever changing natural patterns, one views the homogenous color of an applied paint. In principle, such paint can be removed from fine wood, but there are many disadvantages associated with stripping paint, from many different perspectives: It can be quite harmful to the individual as well as the overall environment. This situation in the formal dining room can be seen in the image shown herein. In addition to the paint in the dining room, paint had been applied to much of the fine woodwork around the doors and windows on the second floor.

Floor Plan Alterations

The restoration craftsman (Peter J. Fears) along with the restoration architect (David Hoffman) have concluded that the house had not undergone any major changes in the basic floor plan since its original construction, with one exception. It seems reasonable to conclude, based upon a variety of structural clues, that the small kitchen was not part of the original structure created by Robert C. Lambie for John Southgate.

A Home Once Again

Following the restoration of the Southgate–Lewis House, Albrecht moved into the home with his family. During this period of time, the house became a focal point for academic meetings and functions associated with The University of Texas at Austin. Nobel Laureates (e.g., Torsten N. Wiesel,[69] David H. Hubel[70]), world renowned scientists (e.g., Horace B. Barlow,[71] Russell L. De Valois[72]), and other academic dignitaries from the University of Texas at Austin (e.g., Abram Amsel,[73] Wilson S. Geisle,r[74] William B. Swann) were frequent visitors to the Southgate-Lewis House.

In gratitude for all of the support provided by the Austin Community in the quest to save and restore the Southgate-Lewis House, Albrecht served on the Board of Directors for The Heritage Society of Austin for two decades, becoming the Treasurer and First Vice President. He also severed on the Board of Directors for the historic Paramount Theatre.

Donation to the Passon Society

After living in the home for some long time, encouraged by Ada Marie DeBlanc Simond, Duane G. Albrecht donated the Southgate–Lewis House to the W.H. Passon Historical Society[13][8][75] in December of 1986. The goal of the Passon Society is to secure and preserve materials (journals, books, periodicals, exhibits, et cetera) related to African-American Black history and to establish an educational center for the purpose of research into the topic and the acquisition of related knowledge. The Southgate-Lewis House seemed like the ideal home for the W.H. Passon Historical Society, and reciprocally, the W.H. Passon Historical Society seemed like the ideal steward for the historic preservation of the Southgate-Lewis House.

W.H. Passon Historical Society

Purpose and Goal

The W.H. Passon Historical Society is an organization that strives to secure and preserve materials and artifacts related to Black culture in Austin and Travis County, Texas. The Society was founded by Ada Marie DeBlanc Simond (with Janie Beatrice Perry Harrison[76] and Fannie Mae Murphy Lawless). The Society was first organized in 1975 (by Ada Simond) and then chartered by the State of Texas in 1979. The stated purpose is "To unite all individuals within and without the Black Community who have a genuine interest in the Past, and an eagerness to discover the depth and breadth of the Black Experience in Austin and Travis County." The stated goal is "To secure, preserve and legitimize events, documents and artifacts related to the Black Culture in Austin and Travis County [and to] recognize and reward the efforts of individuals and organizations which protect, enhance and reflect respect for the Black Heritage of our community."[77]

The Southgate-Lewis House

The Southgate–Lewis House is now the home of the W.H. Passon Historical Society.[78][46] The objective of the historical society for the Southgate-Lewis House is "to establish an educational center including books, journals, exhibits, periodicals, and other materials by and about Black People for the purpose of research and to broaden the knowledge of the citizenry relative to the contributions of Black People.[77] The Southgate-Lewis House stands as an important African-American Historical Landmark and as a repository for African-American history and culture.[79]

Wesley H. Passon

Educator

Wesley H. Passon (1864-1933) was a Black educator who made many important contributions toward the preservation of African-American history, most notably a summary of the history of the African-American population in Austin, Texas. In 1894, Mr. Passon was elected to the position of principle of the school in Wheatville Texas, which was the first Black community associated with Austin after the Civil War, located just west of The University of Texas at Austin.[80] The community of Wheatville was founded in 1867 by James Wheat, a former slave from Arkansas.[81] The location that was once Wheatville (24th street to 26th street, Rio Grande street to the shoal creek) is now primarily student housing and it contains the majority of all of the sororities and fraternaties at The University of Texas at Austin. W.H. Passon then went on to serve as principle of many other early schools of Austin Texas such as Blackshear School which: "opened in 1891 to provide free public education to African-American children in the community."[82] He was the priniciple of West Austin School, Clarksville School, Olive Street School, and Gregorytown. Two journals record the daily affairs of the West Austin School and the Clarksville School from 1908 to 1918.[46]

Historian

W.H. Passon was a faithful member of the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Austin.[83] In 1907, W.H. Passon provided a comprehensive historical record for the Church that has since become an essential resource for scholars and others to this very day. For example: In September of 2000, the City of Austin Texas Historic Resources Survey of East Austin, stated that "One of the most important secondary sources obtained for historical research in East Austin was the 1907 Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) ... [book] ... compiled by historian W.H. Passon: The Historical and Biographical Souvenir and Program of the 25th Anniversary of Metropolitan AME Church, Austin, Texas 1882-1907."[33][84]

Ada Marie DeBlanc Simond

The Charles M. Lewis Family

Ada Marie DeBlanc Simond (1903-1989) was an African-American teacher, writer, historian, and public health activist who grew up in the neighborhood of the Southgate-Lewis House (and continued to live in the neighborhood throughout her life).[14] She was a staunch and powerful advocate for the historic preservation of the Southgate-Lewis House. Ada Simond knew the Charles M. Lewis family quite well; she was a friend of Mae Dee Lewis and she frequented the Southgate-Lewis House often. Charles M. Lewis was also a close friend and mentor and he allowed Ada Simond to audit classes at Samuel Huston College (where he was a professor). Later she would go on to acquire a masters degree at Iowa State University.

Six Book Series

Ada Simond used the Lewis family and the Southgate–Lewis House as inspiration for a series of children's books relating to Black history in East Austin. She published a series of six children’s books entitled Let’s Pretend: Mae Dee and Her Family (beginning with Let’s Pretend: Mae Dee and Her Family Go to Town in 1977),[85] in which she told historically accurate stories of Black families living in Austin in the early 1900s. These books are "narrated by Mae Dee Lewis, whom Simond identified as a childhood friend."[86] The six book series was named "Outstanding Publication on a History Subject" by the Texas Historical Commission in 1979. Ada Simond also wrote a weekly column for The Austin American Statesman for several years entitled "Looking Back," which highlighted the historical roots of Austin's African-American community.[87]

Academic Background

Ada Simond holds a master’s degree in home economics from Iowa State University and she taught at Tillotson College between 1936 and 1942. In 1982 Huston-Tillotson College conferred upon her a Doctor of Humane Letters. She was a lifetime member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the National Council of Negro Women. She has received numerous awards: e.g., The Black Heritage Award from the Austin Independent School District, and The Human Relations Award from the Texas State Teachers Association.[88]

George Washington Carver Museum

Ada Simond cofounded the George Washington Carver Museum,[89][90][91] which opened in a historic building that was once the site of Austin’s first Black library. The Carver Museum is located only two blocks away from the Southgate-Lewis House. In addition to the awards mentioned above Ada Simond also received the Arthur B. DeWitty Award for "outstanding effort and achievement in human rights." She was inducted into the Texas Women's Hall of Fame in 1986. The City of Austin, Texas has named a street in her honor.[92]

W.H. Passon Society

In 1975, Ada Simond organized the W. H. Passon Historical Society to help secure and preserve the history of Austin’s African-American community.

Juneteenth National Independence Day

On June 19, 2021, the annual Juneteenth Celebration became the newest federal holiday: officially, Juneteenth National Independence Day (Jubilee Day, Emancipation Day, Freedom Day, and Black Independence). This traditional annual celebration commemorates the ending of slavery in the United States – the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. A photograph of the Southgate-Lewis House shows how the home of the W.H. Passon Historical Society was utilized on the very day the new Juneteenth National Independence Day was celebrated. The banners on the west elevation of the house (shown herein) depict distinguished African Americans in Government, Education, Literature, Medicine, and Sports. The banners on the north elevation (shown herein) depict distinguished African Americans in Religion and the Military.

Association with Educators

It is worth noting that throughout its long history, the Southgate-Lewis House seems to have been associated with educators of one sort or another. The history of the house begins with the bookbinder, John Southgate. (Books are certainly associated with education.) Charles Lewis and Mae Dee Lewis were both educators. The University of Texas professor was an educator. (Nobel Laureates, scientists, et cetera, are educators.) Wesley H. Passon was a distinguished Black educator. And finally, the purpose of the W.H. Passon Historical Society is to "establish an educational center."

Landmark status designation and recognition

- 1979 – Designated a City of Austin landmark[3]

- 1980 – Awarded the Heritage Society of Austin Historic Preservation Award[4][5]

- 1985 – Designated a landmark by the National Register of Historic Places[6][7]

- 1987 – Recognized by the State of Texas 70th Legislature, Resolution No. 141, for ensuring the legacy of Black heritage in Austin[8]

- 1987 – Awarded the "Helping Hands Award for Community Service" by the Texas Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History[9]

- 1988 – Designated a Recorded Texas Historic Landmark[10][11]

References

- ^ "W.H. Passon Historical Society".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ University of Texas at Austin. "The Daily Texan, Iconic House Embodies Black History".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Southgate–Lewis House C14H- 1978-0024. "City of Austin Historic Landmarks by Address" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Austin History Center Periodicals Collection. "Heritage Society of Austin, The 1886 Gazette" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Preservation Austin. "Preservation Austin Celebrates 60 Years of Preservation Merit Award Winners".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b United States Department of the Interior. "National Register of Historic Places; National Register Listings 2/1/2012" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b National Register of Historic Places Inventory. "Southgate-Lewis House" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h State of Texas 70th Legislature. "House Concurrent Resolution No. 141" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Texas Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History. "University of Texas at Austin Briscoe Center for American History".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Texas Historic Sites Atlas — Atlas Number 5507015230. "Designated a Recorded Texas Historic Landmark; RTHL Medallion and Plate; Marker 15230".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Texas Historical Commission. "Recorded Texas Historical Landmarks".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b University of Texas at Austin. "The Daily Texan, Iconic House Embodies Black History".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Texas State Historical Association. "Simond, Ada Marie DeBlanc (1903-1989)".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. "Stick Style 1860-1890".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Old House. "Study of Stick Style Architecture and History".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ This Old House. "Gingerbread Trim".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Vintage Woodworks. "Running Trims".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Dotdash: The Spruce (09/23/2020). "What is Victorian Architecture".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Dotdash: Tripsavvy (08/06/2019). "Victorian Houses of San Francisco".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Department of Archeology and Historic Preservation of Washington State. "Stick Style, 1870-1895".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Minnesota Historical Society. "The Bric-a-Brac Styles" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Buffalo as an Architectural Museum. "Eastlake Style in Buffalo, New York".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ McAlester, Virginia McAlester. "A Field Guide to American Houses; The Definitive Guide to Identifying and Understanding America's Domestic Architecture".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Cambridge Historical Commission. "350 Years, Variety of Architectural Styles" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Metropolitan Museum of Art. "Assyrian Crown-Prince ca. 704-681 B.C."

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Holtzapffel, John Jacob (1976). Hand or Simple Turning (reprint of 1881 London series ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-26428-9.

- ^ Stanley-Stone, A.C. (1925). The Worshipful Company of Turners of London (drawn from records of the Company ed.). London: Lindley-Jones and Brother.

- ^ Child, Peter (1997). The Craftsman Woodturner (first published 1971 ed.). London: Guild of Master Craftsmen Publications LTD. ISBN 1-86108-075-1.

- ^ Texas State Historical Association. "Robertson Joseph William (1809-1870)".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Briscoe Center for American History. "A Guide to the Joseph William Robertson Papers, 1840-1940".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Texas Historical Commission. "French Legation State Historic Site".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b City of Austin, Texas Historic Resources Survey, September 2000. "Historic Resources Survey of East Austin".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Austin History Center. "Everything Austin: Population Statistics".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Texas Historic Sites Atlas, Texas Historical Commission. "East Austin" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ United States Department of the Interior National Register of Historic Places. "Historic Resources of East Austin".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ William J. Hill Texas Artisans & Artists Archives. "Eugene Von Boeckmann".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The University of Texas at Austin, Alexander Architectural Archive. "University of Texas buildings collection".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The University of Texas at Austin, UT Campus History. "Old Engineering Building (Gebauer Building)".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Briscoe Center for American History. "Digital Media Repository: Old Engineering Building, University of Texas at Austin".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Cultural Landscape Foundation. "Elisabet Ney Museum".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Texas State University. "Old Main".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ American Courthouses. "Hays County Courthouse".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Austin History Center, Texas Archival Resources Online. "Anderson High School Papers".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Michael Mixerr Local Austin Business Reviews. "History of Robertson Hill School (Robertson Hill High School) in Austin, explained and examined. November 16, 2020".

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Austin History Center. "W.H. Passon Historical Society Records".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ University of Texas at Austin. "Center for Perceptual Systems".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Austin History Center. "Heritage Society of Austin Records".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Preservation Austin (previously entitled The Heritage Society of Austin). "Preservation Austin".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Austin History Center. "David Hoffman & Co. Records and Drawings".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Austin History Center. "Bell, Klein, & Hoffman Records and Drawings".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Austin American Statesman. (September 25, 2018). "Director of Downtown Austin Alliance to retire".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Austin Business Journal. (March 14, 2014). "After 17 years, Downtown Austin Alliance chief to retire".

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Austin Monthly. (December 2016). "The Rebirth of Congress Avenue".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Library of Congress. (1982). "Franklin Savings Tips Building, South Congress Street [i.e. 710 Congress Ave.], Austin, Texas".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Texas Historical Markers. "The Walter Tips Company Building".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Portal to Texas History. "The Walter Tips Company Building".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Austin American Statesman. "The Limerick-Frazier House on East 13th Street".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Black history in Austin: 15 notable landmarks. "The Limerick-Frazier House".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Culture Map Austin. "Limerick-Frazier House".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bob Vial Tried, True, Trustworthy Home Advice. "5 Things to Know About Lath and Plaster Walls".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ American Institute of Architects. "Why shiplap siding has stood the test of time".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Woodwork Details. "Shiplap Edge Joints".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ William J. Hill Texas Artisans & Artists Archive. "Calcasieu Lumber Co".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Towers. "When Calcasieu Lumber Ruled Austin's Wood Game, We Never Ran Low on Logs".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Austin History Center. "Calcasieu Lumber Company Records".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Iowa State University. "The Calcasieu Pine District of Louisiana" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ American Press. [ttps://www.americanpress.com/news/local/longleaf-pine-has-rich-history-in-southwest-louisiana/article_23122a7e-d9a1-5bb3-95fc-e143553867d3.html "Longleaf pine has rich history in Southwest Louisiana"].

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Nobel Prize. "Torsten N. Wiesel".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Nobel Prize. "David H. Hubel".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Royal Society. "Horace Barlow".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ National Academy of Sciences. "Russell L. De Valois".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ National Academy of Sciences. "Abram Amsel".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ National Academy of Sciences. "Wilson S. Geisler".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ County Clerk, Travis County, Texas. "Warranty Deed, Grantor: Albrecht Duane G, Instrument # 1002500144, filed 12/23/1986, 3:22 PM, Book 10025, Page 144".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Austin Public Library. "The W.H. Passon Historical Society and Its Evolution Into the Southgate-Lewis House".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b The Portal to Texas History. "W.H. Passon Historical Society".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "W.H. Passon Historical Society".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Visitors Bureau Austin Texas, African American Historical Landmarks. "Southgate-Lewis House, W.H. Passon Historical Society".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Official Website of The City of Austin. "African American Rural Schools of Travis County".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Texas State Historical Association. "Wheatville, Texas (Travis County)".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Historical Marker Database. "Blackshear Elementary School".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Historical Marker Database. "Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Austin Public Library. "The Historical and Biographical Souvenir and Program of the 25th Anniversary of Metropolitan A.M.E. Church Austin, Texas, 1882-1907, May 6th to 14th 1907".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Amazon Books. "Let's Pretend Mae Dee and Her Family Go to Town; The First in a Series of Stories".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Grider, Sylvia (1997). Texas Women Writers: A Tradition of Their Own (Vol. 8). Texas A&M University Press. p. 248. ISBN 0-89096-752-0.

- ^ Austin, Austin History Center. "Defining Legacies for the Love of Austin".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Texas Women's Hall of Fame, Texas Women's University. "Ada Simond, 1986 Inductee Civic Leadership".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Texas State Historical Association. "George Washington Carver Museum".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ City of Austin Texas. "George Washington Carver Museum, Cultural and Genealogy Center".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Towers News, May 7, 2021. "East Austin's George Washington Carver Museum is Ready to Grow".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Mueller Foundation. "The Legacy of Austin at Mueller | A History of Section 6 Street Signs".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

- National Register of Historic Places in Austin, Texas

- Houses on the National Register of Historic Places in Texas

- Houses in Austin, Texas

- Museums in Austin, Texas

- African-American museums in Texas

- Religious museums in Texas

- 1888 establishments in Texas

- Recorded Texas Historic Landmarks

- City of Austin Historic Landmarks

- Texas building and structure stubs