Scytho-Siberian world

| |

| Geographical range | Eurasian Steppe |

|---|---|

| Period | Iron Age |

| Dates | c. 900 BCE-200 CE |

| Preceded by | Srubnaya culture, Andronovo culture |

| Followed by | Goths, Alans, Xiongnu |

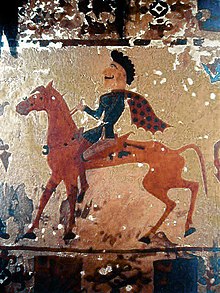

Scythian cultures[a] were a group of similar archaeological cultures which flourished across the entire Eurasian Steppe during the Iron Age from approximately the 9th century BCE to the 2nd century CE. Among Greco-Roman writers, this region was called Scythia, with the name eventually broadened to refer to essentially all the tribal people north and east of the Black Sea by the name of the first tribe the Greeks traded with.

The Scythian cultures are characterized by the Scythian triad, which are similar, yet not identical, styles of weapons, horses' bridles, and jewelry and decorative art. The question of how related these cultures were is disputed among scholars. Its peoples were of diverse origins, and included not just Scythians, from which the cultures are named, but other peoples as well, such as the Cimmerians, Massagetae, Saka, Sarmatians, and obscure forest steppe populations. Mostly speakers of the Scythian branch of the Iranian languages,[b] all of these peoples are sometimes collectively referred to as Scythians, Scytho-Siberians, Early Nomads, or Iron Age Nomads.[2]

Origins and spread

The Scythian cultures emerged on the Eurasian Steppe at the dawn of the Iron Age in the early 1st millennium BCE. The origins of the Scythian cultures has long been a source of debate among archaeologists.[3] The Pontic–Caspian steppe was initially thought to have been their place of origin, until the Soviet archaeologist Aleksey Terenozhkin suggested a Central Asian origin.[2][4]

Recent excavations at Arzhan in Tuva, Russia have uncovered the earliest Scythian-style kurgan yet found.[5] Similarly the earliest examples of the animal style art which would later characterize the Scythian cultures have been found near the upper Yenisei River and North China, dating to the 10th century BCE. Based on these finds, it has been suggested that the Scythian cultures emerged at an early period in southern Siberia.[2] It is probably in this area the Scythian way of life initially developed.[1][6] Recent genetic studies have concluded that the Scythians formed from European-related groups of the Yamnaya culture and East Asian/Siberian groups during the Bronze Age and early Iron Age.[7][4][2][8]

The Scythian cultures quickly came to stretch from the Pannonian Basin in the west to the Altai Mountains in the east.[9] There were however significant cultural differences between east and west.[4] Over time they came in contact with other ancient civilizations, such as Assyria, Greece and Persia. In the late 1st millennium BCE, peoples belonging to the Scythian cultures expanded into Iran (Sakastan), India (Indo-Scythians) and the Tarim Basin.[10] In the early centuries CE, the western Scythian cultures came under pressure from the Goths and other Germanic peoples.[10] The end of the Scythian period in archaeology has been set at approximately the 2nd century CE.[1]

Peoples

Ethnicity

The peoples of the Scythian cultures are mentioned by contemporary Persian and Greek historians. They were mostly speakers of Iranian languages.[b]

Despite belonging to similar material cultures, the peoples of the Scythian cultures belonged to many separate ethnic groups.[11][12] Peoples associated with the Scythian cultures include speakers of the Scythian languages:[2][13]

- Massagetae,[2]

- Sarmatians,[2]

- Saka,[2]

- Scythians,[2]

- Cimmerians,[13] and the

- forest steppe people.[13]

Although the peoples of the forest steppe were part of the greater Scythian culture, their origins are obscure;[13] there might have been

among them.[14][15] The settled population in Scythian cultural areas also included

Terminology

Among the diverse peoples of the Scythian cultures, the Scythians are the most famous, due to the reports on them published by the 5th century Greek historian Herodotus. The ancient Persians referred to all nomads of steppe as Saka. In modern times, term Scythians is sometimes applied to all the peoples associated with the Scythian cultures.[14] Within this terminology it is often distinguished between "western" Scythians living on the Pontic–Caspian steppe, and "eastern" Scythians living on the Eastern Steppe.[2][10]

The terms Saka or Sauromates, and Scytho-Siberians, is sometimes used for the "eastern" Scythians living in Central Asia and southern Siberia respectively.[7][16] The term Scytho-Siberians has also been applied to all peoples associated with the Scythian cultures.[17] The terms Early Nomads[18] and Iron Age Nomads have also been used.[4]

The ambiguity of the term Scythian has led to a lot of confusion in literature.[c][13]

Di Cosmo (1999) questions the validity of referring to the cultures of all early Eurasian nomads as "Scythian", and recommends the use of alternative terms such as Early Nomadic.[20][d]

By ancient authors, the term "Scythian" eventually came to be applied to a wide range of peoples "who had no relation whatever to the original Scythians", such as Huns, Goths, Türks, Avars, Khazars, and other unnamed nomads.[10]

Characteristics

The Scythian cultures are recognized for three characteristics known as the Scythian triad:[13][16]

- similar, yet not identical, shapes for horses' bridles,

- their weapons, especially their distinct short, compound bows, and

- the styling on their jewelry and decorations.

Their art was made in the animal style, so characteristic that it is also called Scythian art.

Finds

In the beginning of the 18th century, Russian explorers began uncovering Scythian finds throughout their newly acquired territories.

Significant Scythian archaeological finds have been uncovered up to recent times. A major find are the Pazyryk burials, which were discovered on the Ukok Plateau in the 1940s. The finds are notably for revealing the form of mummification practiced by the Scythians.[1] Another important find is the Issyk kurgan.[6]

Society

The Scythians were excellent craftsmen with complex cultural traditions. Horse sacrifices are common in Scythian graves, and several of the sacrificed horses were evidently old and well-kept, indicating that the horse played a prominent role in Scythian society.[1] They played a prominent role in the network connecting ancient civilizations known as the Silk Road.[10] The homogeneity of patrilineal lineages and contrasting diversity of matrilineal lineages of samples from Scythian burial sites indicate that Scythian society was strongly patriarchal.[16]

Numerous archaeological finds have revealed that the Scythians led a warlike life: Their competition for territory must have been fierce. The numerous weapons placed in graves are indicative of a highly militarized society. Scythian warfare was primarily conducted through mounted archery. They were the first great power to perfect this tactic. The Scythians developed a new, powerful type of bow known as the Scythian bow. Sometimes they would poison their arrows.[1]

Physical appearance

They were tall and powerfully built, even by modern standards.[e] Anthropometric and genetic data have revealed that the people of the Scythian cultures were mostly Europoid, with Mongoloid admixture discernible on the eastern fringes.

Skeletons of Scythian elite differ from those of today by their longer arms and legs, and thicker, stronger bones. This was particularly the case for warriors and elite men, who were often more than 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) tall. Sometimes they exceeded 1.9 m (6 ft 3 in) in height; even a few remains of Scythian men taller than 2.0 m (6 ft 6 in) have been excavated. The common people whom they dominated were much smaller and lighter, averaging 10–15 cm (4–6 in) shorter than the elite.[21]

Their physical traits are characteristic of Iranian peoples and support a common origin indicated by the genetic and linguistic evidence.[e][21]

Genetics

The genetics of remains from Scythian-identified cultures show broad general patterns, among these are remarkably different histories for men and women. Their ethnic affiliations are summarized above. Their familial inter-relations are discussed below.

There are two distinct paternal lineages in the east and west,[2][4][16] with the eastern and western paternal lineages being themselves homogeneous.[1] The paternal western Scythian haplogroups are closely related to modern Europeans,[3] but disappeared from the Scythian steppe region,[4] being eventually replaced by the eastern Scythians,[22] who then were themselves replaced by paternal lines of other Eurasian cultures.[1] The surviving modern populations most closely related to the paternal Scythian lineages are in Europe; apparently none remain in mid- and northern-Asia.[3][16]

In contrast, the maternal lineages among Scythians are diverse,[2][4][16] and the eastern and western maternal lines were significantly mixed.[1][7][22] The free intermarriage of women across all of the Scythian cultures could be what maintained trans-Scythian cultural coherence.[2] Further, rather than dying out, local maternal Scythian lineages persist among modern people living near the excavated graves.[2]

Western Scythian culture genetics

This section lists the findings of genetic studies of the remains excavated in western Asia ascribed to one of the Scythian cultures.

Mathieson & Reich (2015)[23][24] analyzed the remains of an individual from Samara Oblast, Russia, dated c. 380–200 BCE and ascribed to the Scythian cultures. The individual was found to belong to haplogroup R1a1a1b2a2a.[23][24] This lineage is associated with earlier Srubnaya culture of the Pontic–Caspian steppe, which again traces its origin to the Yamnaya culture.[7]

Unterländer (2017),[2] in a genetic study of various Scythian cultures, suggested that the Scythian cultures on the Pontic-Caspian steppe and the Eastern Steppe emerged independently of each other, and were a mixture of Yamnaya culture-related and East Asian ancestry. Much of this admixture probably happened during the earlier expansion of the Afanasievo culture and Andronovo culture onto the Eastern Steppe. The peoples of the areas of the Scythian cultures were more closely related to each other than modern populations in the same areas, and there appears to have been significant gene flow between them,[1] mostly maternal (mitochondrial) lineages from east to west.[2]

Unterländer suggested that this gene flow may indicate one source of the uniformity of the Scythian cultures, carried in the (diverse) maternal lines. Modern populations with a close genetic relationship to the peoples of the Scythian cultures were found to be those living in close proximity to the remains examined, suggesting genetic continuity.[2]

Juras (2017)[7] reported similar results in another genetic study, which found and increasing number of east Eurasian mitochondrial lineages among the eastern Scythian cultures. The origins of east Eurasian lineages present in Scythian samples was explained as a result of admixture between migrants of European ancestry and women of east Eurasian origin. The authors of the study suggested that the Srubnaya culture was the source of the Scythian cultures of at least the Pontic steppe.[7]

Krzewińska (2018)[4] studied the genetics of the earlier Srubnaya culture, and peoples of the later Scythian cultures, such as Cimmerians, Scythians, and Sarmatians. While members of the Srubnaya culture were found to be carriers of haplogroup R1a1a1, which showed a major expansion during the Bronze Age, the Cimmerian, Scythian, and Sarmatian samples examined were found to be mostly carriers of haplogroup R1b1a1a2, which is characteristic of the earlier Yamnaya culture, although one Sarmatian studied did carry haplogroup R1a1a1. Peoples of the Scythian cultures were also found to have a presence of east Eurasian mitochondrial lineages, which are completely absent among the Srubnaya.[4]

Groups of the Scythian cultures in the west showed close genetic affinities with the Afanasievo culture and the Andronovo culture, while groups in the east, such as those of the Aldy-Bel culture and Pazyryk culture, showed closer genetic affinities with the Yamnaya culture. Genetic data found negligible evidence of any mobility among populations in the Far East, suggesting the eastern Pontic–Caspian steppe and the southern Urals as the main source of origin of the western Iron Age nomads. Rather than being directly descended from the Srubnaya culture, the Scythian cultures probably had a shared origin in the Yamnaya culture. The study corroborated the contention that the peoples of the Scythian cultures did not consist of a single homogeneous group, but rather a number of diverse peoples with an earlier common origin.[4]

Järve (2019)[3] studied genetics of various peoples belonging to the Scythian cultures, such as Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, and Saka. Mostly of the remains in all groups were found to carry various subclades of haplogroup R1a, with a few haplogroup Q samples also found (only 2 Y-DNA samples, out of 160 identified). The samples are more closely related to modern-day Europeans than any modern people native to central Asia or Siberia.[3]

Eastern Scythian culture genetics

This section lists the findings of genetic studies of the remains excavated in central Eurasia and the eastern steppe ascribed to one of the Scythian cultures.

Pilipenko (2018)[22] studied mtDNA from remains of the Tagar culture, which is considered a Scythian culture. Although found in turkic Khakassia, at the eastern extreme of the Eurasian steppe, remains from the early years of the Tagar culture were found to be closely related to those of contemporary Scythians on the Pontic steppe far to the west. The authors suggested that the source of this genetic similarity was an eastwards migration of west Eurasians during the Bronze Age, which probably contributed to the formation of the Tagar culture.[22]

Mary (2019)[16] studied the genetics of remains from the Aldy-Bel culture in and around Tuva in central Asia, adjacent to western Mongolia; the Aldy-Bel culture is considered one of the Scythian cultures. The majority of the samples (9 out of 17) were found to be carriers of haplogroup R1a, including two carriers of haplogroup R1a1a1b2‑Z93. East Asian admixture was also detected, as 6 haplogroup Q-L54 (including 5 in Sagly culture) and 1 haplogroup N-M231 were excavated. The haplogroup of the remaining 1 sample was uncertain (probably group R)[disambiguation needed].[16]

The Scythian groups of the Pontic Steppe and South Siberia had significantly different paternal genetics, which indicates that the Pontic and South Siberian Scythians had completely different paternal origins, with almost no paternal gene flow between them.[16][f]

See also

Notes

- ^ Also referred to as Scythic cultures, Scytho-Siberian cultures, Early Nomadic cultures, the Scythian civilization, the Scythian horizon, the Scythian world, or the Scythian continuum.

- ^ a b "[A] nomadic people made up of many different tribes thrived across a vast region that stretched from the borders of northern China and Mongolia, through southern Siberia and northern Kazakhstan, as far as the northern reaches of the Black Sea. Collectively they were known by their Greek name: the Scythians. They spoke Iranian languages ..."[1]

- ^ "The Achaemenids called the Scythians "Saka" which sometimes leads to confusion in the literature. The term "Scythians" is particularly used for the representatives of this culture who lived in the European part of the steppe zone. Those who lived in Central Asia are often called Sauromates or Saka and in the Altai area, they are generally known as Scytho-Siberians."[19]

- ^ "Even though there were fundamental ways in which nomadic groups over such a vast territory differed, the terms "Scythian" and "Scythic" have been widely adopted to describe a special phase that followed the widespread diffusion of mounted nomadism, characterized by the presence of special weapons, horse gear, and animal art in the form of metal plaques. Archaeologists have used the term "Scythic continuum" in a broad cultural sense to indicate the early nomadic cultures of the Eurasian steppe. The term "Scythic" draws attention to the fact that there are elements - shapes of weapons, vessels, and ornaments, as well as lifestyle - common to both the eastern and western ends of the Eurasian steppe region. However, the extension and variety of sites across Asia makes Scythian and Scythic terms too broad to be viable, and the more neutral "early nomadic" is preferable, since the cultures of the Northern Zone cannot be directly associated with either the historical Scythians or any specific archaeological culture defined as Saka or Scytho-Siberian."[20]

- ^ a b "[T]he [elite] Scythians were relatively tall. This tallness is particular noticeable in warrior burials and those of men of the upper social stratum, who would seem tall even today ... [T]hese skeletons differ from those of today in their longer arm and leg bones and a generally stronger bone formation ... The physical characteristics of the Scythians correspond to their cultural affiliation: [T]heir origins place them within the group of Iranian peoples ... [W]e are dealing with a period in which huge areas of Siberia far into Mongolia were still inhabited by ancient Europoids."[21]

- ^ "The absence of R1b lineages in the Scytho-Siberian individuals tested so far and their presence in the North Pontic Scythians suggest that these two groups had a completely different paternal lineage makeup with nearly no gene flow from male carriers between them."[16]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Simpson 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Unterländer 2017Genomic inference reveals that Scythians in the east and the west of the steppe zone can best be described as a mixture of Yamnaya-related ancestry and an East Asian component. Demographic modelling suggests independent origins for eastern and western groups with ongoing gene-flow between them, plausibly explaining the striking uniformity of their material culture. We also find evidence that significant gene-flow from east to west Eurasia must have occurred early during the Iron Age. The origin of the widespread Scythian culture has long been debated in Eurasian archaeology. The northern Black Sea steppe was originally considered the homeland and centre of the Scythians3 until Terenozhkin formulated the hypothesis of a Central Asian origin4. On the other hand, evidence supporting an east Eurasian origin includes the kurgan Arzhan 1 in Tuva5, which is considered the earliest Scythian kurgan5. Dating of additional burial sites situated in east and west Eurasia confirmed eastern kurgans as older than their western counterparts6,7. Additionally, elements of the characteristic ‘Animal Style’ dated to the tenth century BCE1,4 were found in the region of the Yenisei river and modern-day China, supporting the early presence and origin of Scythian culture in the East. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEUnterländer2017" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e Järve 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Krzewińska 2018The nomadic populations were heterogeneous and carried genetic affinities with populations from several other regions including the Far East and the southern Urals. Genetic analyses of maternal lineages of Scythians suggest a mixed origin and an east-west admixture gradient across the Eurasian steppe (10–12). The genomics of two early Scythian Aldy-Bel individuals (13) showed genetic affinities to eastern Asian populations (12). Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEKrzewińska2018" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Medrano, Kastalia (2018-01-12). "The undisturbed tomb of a Scythian prince was found frozen in time in Siberia". Newsweek. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- ^ a b Alekseev 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Juras 2017.

- ^ Gnecchi-Ruscone, Guido Alberto; Khussainova, Elmira; Kahbatkyzy, Nurzhibek; Musralina, Lyazzat; Spyrou, Maria A.; Bianco, Raffaela A.; Radzeviciute, Rita; Martins, Nuno Filipe Gomes; Freund, Caecilia; Iksan, Olzhas; Garshin, Alexander (2021-03). "Ancient genomic time transect from the Central Asian Steppe unravels the history of the Scythians". Science Advances. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe4414. PMC 7997506. PMID 33771866.

Our findings shed new light onto the debate about the origins of the Scythian cultures. We do not find support for a western Pontic-Caspian steppe origin, which is, in fact, highly questioned by more recent historical/archeological work (1, 2). The Kazakh Steppe origin hypothesis finds instead a better correspondence with our results, but rather than finding support for one of the two extreme hypotheses, i.e., single origin with population diffusion versus multiple independent origins with only cultural transmission, we found evidence for at least two independent origins as well as population diffusion and admixture (Fig. 4B). In particular, the eastern groups are consistent with descending from a gene pool that formed as a result of a mixture between preceding local steppe_MLBA sources (which could be associated with different cultures such as Sintashta, Srubnaya, and Andronovo that are genetically homogeneous) and a specific eastern Eurasian source that was already present during the LBA in the neighboring northern Mongolia region (27).

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Kennedy 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Nicholson 2018, pp. 1346–1347.

- ^ David & McNiven 2018, p. 156.

- ^ Watson 1972, p. 142.

- ^ a b c d e f Ivanchik 2018.

- ^ a b West 2002, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Davis-Kimball, Bashilov & Yablonsky 1995, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mary 2019.

- ^ Jacobson 1995, pp. 36–37.

- ^ David & McNiven 2018.

- ^ Ancient Nomads of the Altai Mountains: Belgian-Russian multidisciplinary archaeological research on the Scytho-Siberian culture. Royal Museums of Art and History. 2000. p. 18.

- ^ a b di Cosmo 1999, p. 891.

- ^ a b c Rolle 1989, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b c d Pilipenko 2018.

- ^ a b Mathieson & Reich 2015.

- ^ a b Mathieson 2015.

Bibliography

- di Cosmo, Nicola (1999). "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China (1,500–221 BC)". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the origins of civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 885–996. ISBN 0521470307.

- David, Bruno; McNiven, Ian J. (2018). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190607357.

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine; Bashilov, Vladimir A.; Yablonsky, Leonid T. [in Russian] (1995). Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age. Zinat Press. ISBN 9781885979001.

- Ivanchik, Askold (April 25, 2018). "Scythians". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Jacobson, Esther (1995). The Art of the Scythians: The interpenetration of cultures at the edge of the Hellenic world. BRILL. ISBN 9004098569.

- Juras, Anna (March 7, 2017). "Diverse origin of mitochondrial lineages in Iron Age Black Sea Scythians". Nature Communications. 7: 43950. Bibcode:2017NatSR...743950J. doi:10.1038/srep43950. PMC 5339713. PMID 28266657.

- Järve, Mari (July 22, 2019). "Shifts in the genetic landscape of the western Eurasian steppe associated with the beginning and end of the Scythian dominance". Current Biology. 29 (14): 2430–2441. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.019. PMID 31303491.

- Kennedy, Maev (May 30, 2017). "British Museum to go more than skin deep with Scythian exhibition". The Guardian.

- Krzewińska, Maja (October 3, 2018). "Ancient genomes suggest the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe as the source of western Iron Age nomads". Nature Communications. 4 (10): eaat4457. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.4457K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat4457. PMC 6223350. PMID 30417088.

- Mary, Laura (March 28, 2019). "Genetic kinship and admixture in Iron Age Scytho-Siberians". Human Genetics. 138 (4): 411–423. doi:10.1007/s00439-019-02002-y. PMID 30923892. S2CID 85542410.

- Mathieson, Iain; Reich, David (March 14, 2015). "Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe". bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/016477.

- Mathieson, Iain (December 24, 2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature. 528 (7583): 499–503. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..499M. doi:10.1038/nature16152. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274.

- Nicholson, Oliver (2018). "Scythians (Saka)". The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. pp. 1346–1347. ISBN 978-0192562463.

- Pilipenko, Aleksandr S. (20 September 2018). "Maternal genetic features of the Iron Age Tagar population from southern Siberia (1st millennium BC)". PLOS One. 13 (9): e0204062. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1304062P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0204062. PMC 6147448. PMID 30235269.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- Rolle, Renate [in German] (1989). The World of the Scythians. University of California Press. ISBN 0520068645.

- Simpson, St. John (2017). "The Scythians: Discovering the nomad-warriors of Siberia". Current World Archaeology. 84: 16–21.

- Unterländer, Martina (March 3, 2017). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. 8: 14615. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814615U. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537.

- West, Stephanie (2002). "Scythians". In Bakker, Egbert J.; de Jong, Irene J.F.; van Wees, Hans (eds.). Brill's Companion to Herodotus. Brill. pp. 437–456. ISBN 978-90-04-21758-4.

Further reading

- Alekseev, Andrei (2017). "8 The Scythians and their cultural contacts". Scythians: Warriors of ancient Siberia. The BP Exhibition. London, UK: British Museum; Thames & Hudson – via Academia.edu. — Good; free download (with registration).

- Cunliffe, Barry (2019). The Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192551863.

- Hinds, Kathryn (2010). Scythians and Sarmatians. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0761445197.

- Lendering, Jona (February 14, 2019). "Scythians / Sacae". Livius.org. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Rolle, Renate [in German] (2011). "The Scythians: Between mobility, tomb architecture, and early urban structures". In Bonfante, Larissa (ed.). The Barbarians of Ancient Europe: Realities and interactions. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0521194044.

- Rice, Tamara Talbot (1957). The Scythians. F.A. Praeger.

- Watson, William (October 1972). "The Chinese contribution to eastern nomad culture in the pre-Han and early Han periods". World Archaeology. 4 (2). Taylor & Francis: 139–149. doi:10.1080/00438243.1972.9979528. JSTOR 123972.

- Articles with links needing disambiguation from July 2021

- Scythian cultures

- 9th-century BC establishments

- 2nd-century disestablishments

- Archaeological cultures of Central Asia

- Archaeological cultures of Eastern Europe

- Archaeological cultures of Northern Asia

- Iranian archaeological cultures

- Iron Age cultures of Asia

- Iron Age cultures of Europe

- Scythia