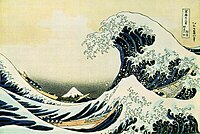

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

| The Great Wave off Kanagawa | |

|---|---|

| 神奈川沖浪裏, Kanagawa-oki Nami Ura | |

Print at the Metropolitan Museum of Art | |

| Artist | Katsushika Hokusai |

| Year | 1831 |

| Type | woodblock print |

| Dimensions | 25.7 cm × 37.9 cm (10.1 in × 14.9 in) |

The Great Wave off Kanagawa (Japanese: 神奈川沖浪裏, Hepburn: Kanagawa-oki Nami Ura, lit. "Under the Wave off Kanagawa")[a] is a woodblock print by the Japanese ukiyo-e artist Hokusai probably made in late 1831 during the Edo period of Japanese history. The print depicts three boats moving through a storm-tossed sea, with a large wave forming a spiral in the centre and Mount Fuji visible in the background.

This print is Hokusai's best-known work and the first in his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, in which the use of Prussian blue revolutionized Japanese prints. The composition of The Great Wave, a synthesis of traditional Japanese prints and Western "perspective", earned him immediate success in Japan, then in Europe, where it was one of the sources of inspiration for the Impressionists. Several museums throughout the world preserve copies of The Great Wave; many come from the great private collections of Japanese prints built up in the 19th century.

The Great Wave is one of the most reproduced and most instantly recognized artworks in the world. It has influenced several notable artists and musicians, including Vincent Van Gogh, Claude Debussy, Claude Monet, Hiroshige and more.

Context

Ukiyo-e art

Ukiyo-e is a Japanese printmaking technique which flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; travel scenes and landscapes; flora and fauna; and erotica. The term ukiyo-e (浮世絵) translates as "picture[s] of the floating world".

After Edo (now Tokyo) became the seat of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate in 1603,[1] the chōnin class (merchants, craftsmen, and workers) benefited the most from the city's rapid economic growth,[2] and began to indulge in and patronise the entertainment of kabuki theatre, geisha, and courtesans of the pleasure districts;[1] the term ukiyo ("floating world") came to describe this hedonistic lifestyle. Printed or painted ukiyo-e works were popular with the chōnin class, who had become wealthy enough to afford to decorate their homes with them.[3]

The earliest ukiyo-e works emerged in the 1670s, with Hishikawa Moronobu's paintings and monochromatic prints of beautiful women.[4] Colour prints were introduced gradually, and at first were only used for special commissions. By the 1740s, artists such as Okumura Masanobu used multiple woodblocks to print areas of colour.[5] In the 1760s, the success of Suzuki Harunobu's "brocade prints" led to full-colour production becoming standard, with ten or more blocks used to create each print. Some ukiyo-e artists specialized in making paintings, but most works were prints.[6] Artists rarely carved their own woodblocks for printing; rather, production was divided between the artist, who designed the prints, the carver, who cut the woodblocks, the printer, who inked and pressed the woodblocks onto hand-made paper, and the publisher, who financed, promoted, and distributed the works. As printing was done by hand, printers were able to achieve effects impractical with machines, such as the blending or gradation of colours on the printing block.[7]

Author

Hokusai was born in Katsushika, Japan, in 1760, in a district east of Edo.[8] At the age of 14, he was named Tokitarō and was the son of a shogun mirrormaker.[9] Because he was never recognised as heir, it is likely that his mother was a concubine.[10]

He began painting when he was six years old, and when he was twelve, his father sent him to work in a bookstore. At sixteen, he became an engraver's apprentice, which he did for three years while also beginning to create his own illustrations. He was accepted as an apprentice to artist Katsukawa Shunshō, one of the greatest ukiyo-e artists of his time, when he was eighteen.[8] When Shunshō died in 1793, Hokusai devoted himself to studying various Japanese and Chinese styles, as well as some Dutch and French paintings on his own. In 1800 he published Famous Views of the Eastern Capital and Eight Views of Edo, and began to accept disciples.[11] It was during this period that he began to use the name Hokusai. During his life he would use more than 30 different pseudonyms.[10]

Hokusai rose to prominence as an artist in 1804 when he created a 240-square-meter drawing of a Buddhist monk named Daruma for a festival in Tokyo.[9] Due to his precarious financial situation, he published Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing in 1812 and began to travel to Nagoya and Kyoto in order to gain more students. In 1814, he published the first of fifteen volumes of sketches, known as manga, in which he drew subjects that interested him, such as people, animals, and Buddha. He published his famous series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji in the late 1820s, and it was so popular that he later had to add ten more prints.[12] Hokusai died in 1849, at the age of 89.[13][14]

It is said that years before his death he stated:[15]

From the age of six, I had a passion for copying the form of things and since the age of fifty I have published many drawings, yet of all I drew by my seventieth year there is nothing worth taking into account. At seventy-three years I partly understood the structure of animals, birds, insects and fishes, and the life of grasses and plants. And so, at eighty-six I shall progress further; at ninety I shall even further penetrate their secret meaning, and by one hundred I shall perhaps truly have reached the level of the marvellous and divine. When I am one hundred and ten, each dot, each line will possess a life of its own.

Description

The Great Wave is of the yoko-e type, i.e. in the form of a landscape, and was produced in an ōban size of 25 cm (9.8 in) high by 37 cm (15 in) wide.[16][17] The landscape is composed of three elements: a storm-tossed sea, three boats, and a mountain, with the signature visible in the upper left-hand corner.

The Mountain

The mountain in the background is Mount Fuji, with its snow-capped summit.[18] Fuji is the central figure of the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, which depicts the mountain from different angles. Mount Fuji is depicted as a blue dot with white highlights in The Great Wave, similar to the wave in the foreground.[19]

The dark colour surrounding Fuji appears to indicate that the painting is set early in the morning, with the sun rising from the viewer's vantage point and beginning to illuminate its snowy peak. There are cumulonimbus clouds between the mountain and the viewer, and although they indicate a storm, there is no rain on Fuji or in the main scene.[20]

Boats

The scene shows three oshiokuri-bune, fast barges that were used to transport live fish from the Izu and Bōsō peninsulas to markets in Edo Bay.[21][22] As the name of the work indicates, the boats are located in Kanagawa Prefecture, with Tokyo to the north, Fuji to the northwest, Sagami Bay to the south, and Edo Bay to the east. The boats return from the capital, facing southwest.[22]

There are eight rowers per boat, who hold on to their oars. There are two more relief crew members at the front of each boat, so there are a total of thirty men in the picture, although only 22 are visible. Using the boats as a reference, one can approximate the size of the wave: the oshiokuri-bune were generally between 12 and 15 metres long, and if one takes into account that Hokusai reduced the vertical scale by 30%, it can be concluded that the wave is between 10 and 12 metres high.[23]

Sea and the waves

The sea dominates the composition, which is based on the shape of a wave that spreads out and dominates the entire scene before falling. At this point, the wave forms a perfect spiral with its centre passing through the centre of the design, allowing to see Mount Fuji in the background. The image is made up of curves: the water's surface is an extension of the curves inside the waves. The big wave's foam curves generate other curves, which are divided into many small waves that repeat the image of the large wave.[19]

Edmond de Goncourt, a French writer, described the wave as follows:[24]

[Drawing] board that was supposed to have been called The Wave. It is much like that almost deified drawing, [created] by a painter gripped by religious terror of a formidable sea that surrounded his country: a drawing that shows [the wave’s] angry ascent to the sky, the deep azure of the curl’s transparent interior, the tearing of its crest that scatters in a shower of droplets in the form of an animal's claws.

The wave is generally described as that produced by a tsunami, rogue wave, or a giant wave, but it is also described as a monstrous or ghostly wave, like a white skeleton threatening the fishermen with its "claws" of foam.[16][25] This fantastic interpretation of the work recalls Hokusai's mastery of Japanese fantasy, as evidenced by the ghosts he drew in his Hokusai Manga. An examination of the wave on the left side reveals many more "claws" ready to seize the fishermen behind the white foam strip. From 1831 to 1832, Hokusai's Hyaku Monogatari series, "One Hundred Ghost Stories", dealt with supernatural themes more explicitly.[26] This image is similar to many of the artist's previous works. The wave's silhouette also resembles that of a dragon, which the author frequently depicts, even on Fuji.[27][28]

Signature

The Great Wave of Kanagawa has two inscriptions. The first, the title of the series, is written in the upper left corner within a rectangular frame, which reads: "冨嶽三十六景/神奈冲/浪裏" Fugaku Sanjūrokkei / Kanagawa oki / nami ura, meaning "Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji / On the high seas in Kanagawa / Under the wave". The second inscription is to the left of the box and bears the artist's signature: 北斎改为一笔 Hokusai aratame Iitsu hitsu which reads as "(painting) from the brush of Hokusai, who changed his name to Iitsu".[29]

Given his humble origins, Hokusai had no surname, and his first nickname, Katsushika, was derived from the region he came from. Throughout his career, he used over 30 different names and never started a new cycle of work without changing his name, sometimes leaving his name to his students.[30]

Depth and Perspective

Depth and perspective (uki-e) work in The Great Wave stand out, with a strong contrast between background and foreground.[31] The two great masses dominate the visual space; the violence of the great wave contrasts with the serenity of the empty background,[17] evoking the yin and yang symbol. Man, powerless, struggles between the two, which may be a reference to Buddhism (man-made things are ephemeral, as represented by the boats being swept away by the giant wave) and Shintoism (nature is omnipotent).[32]

Creation

Hokusai faced numerous challenges during the composition of the work.[22] In his sixties, he had serious financial problems in 1826, apparently had a serious health problem, probably a stroke in 1827, his wife died the following year, and in 1829 he had to rescue his grandson from financial problems, a situation that led him to poverty.[22] Despite sending his grandson to the countryside with his father in 1830, the financial ramifications continued for several years, during which time he was working on the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.[22] Perhaps as a result of these issues, the series were as powerful and innovative.[22] Hokusai's goal for the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji appears to be to depict the contrast between the sacred Mount Fuji and secular life.[33]

After several years of work and other drawings, Hokusai arrived at the final design for The Great Wave in late 1831.[34] There are two similar works from around 30 years before the publication of The Great Wave that can be considered forerunners. These are Kanagawa-oki Honmoku no Zu and Oshiokuri Hato Tsusen no Zu, both works with the same subject matter as The Great Wave:[21][35] a sailing boat in the first case, and a rowing boat in the second, both in the midst of a storm and at the base of a great wave that threatens to engulf them. Hokusai's drawing skill is demonstrated by The Great Wave. The print, though simple in appearance to the viewer, is the result of a lengthy process of methodical reflection. Hokusai established the foundations of this method in his 1812 book Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing, in which he explains that any object can be drawn using the relationship between the circle and the square:[36]

The book consists of showing the technique of drawing using only a ruler and a compass [...] This method starts with a line and the most naturally obtained proportion.

He continues in the book's preface:[36]

All forms have their own dimensions which we must respect [...] It must not be forgotten that such things belong to a universe whose harmony we must not break.

Hokusai returned to the image of The Great Wave a few years later when he produced Kaijo no Fuji for the second volume of One Hundred Views of Fuji. This print features the same relationship between the wave and the mountain, as well as the same burst of foam. There are no humans or boats in the latter image, and the wave fragments coincide with the flight of birds. While the wave in The Great Wave moves in the opposite direction of the Japanese reading – from right to left – the wave and birds in Kaijo no Fuji move in unison.[37]

Reading direction

The Japanese interpretation of the The Great Wave would be from right to left, emphasising the danger posed by the enormous wave.[38] This is traditional for Japanese paintings as the Japanese writing is also read from right to left.[23] Analyzing the boats in the image, particularly the one at the top, reveals that the slender, tapering bow faces to the left, implying that the "Japanese" interpretation is "correct". The boats' appearance can also be analysed in another of Hokusai's prints, Sōshū Chōshi from the series Chie no umi, "Oceans of Wisdom", in which the boat goes against the current, this time in a rightward direction, as shown by the water's wake.[39]

Western influence on the work

Perspective

The concept of perspective prints arrived in Japan in the 18th century. These prints relied on a single-point perspective rather than a traditional foreground, middle ground and background, which Hokusai consistently rejected.[40] Objects in traditional Japanese painting and Far Eastern painting in general were not drawn in perspective, but rather, as in ancient Egypt, the size of objects or figures was determined by the importance of the subject within the context.[41]

Perspective, first used in Western paintings by Paolo Uccello and Piero della Francesca, was introduced to Japanese artists through Western (particularly Dutch) merchants arriving in Nagasaki. Okumura Masanobu, and especially Utagawa Toyoharu, made the first attempts to imitate the use of Western perspective, producing some engravings depicting the canals of Venice or the ruins of ancient Rome in perspective as early as 1750.[42]

Toyoharu's work greatly influenced Japanese landscape painting, which evolved with the works of Hiroshige—an indirect student of Toyoharu through Toyohiro—and Hokusai. Hokusai became acquainted with the Western perspective in the 1790s through Shiba Kōkan's investigations, from whose teaching he benefited. Between 1805 and 1810, he published the Mirror of Dutch Pictures – Eight Views of Edo series.[43]

The Great Wave would undoubtedly not have been as successful in the West if audiences did not have a sense of familiarity with the work. It is, in some ways, a Western play seen through the eyes of a Japanese. According to Richard Lane:[44]

Western students first seeing Japanese prints almost invariably settle upon these two late masters [Hokusai and Hiroshige] as representing the pinnacle of Japanese art, little realizing that part of what they admire is the hidden kinship they feel to their own Western tradition. Ironically enough, it was this very work of Hokusai and Hiroshige that helped to revitalize Western painting toward the end of the nineteenth century, through the admiration of the Impressionists and Post-impressionists.

The "blue revolution"

During the 1830s, Hokusai's prints underwent a "blue revolution", in which he made extensive use of a popular colour known as "Prussian blue".[45] He used this shade of blue for this work,[46] as opposed to the delicate and quickly fading shade of blue that was commonly used in ukiyo-e works at the time, indigo. This Prussian blue, known as berorin ai in Japanese, was imported from Holland beginning in 1820[29] and was used extensively by Hiroshige and Hokusai after their arrival in Japan in large quantities in 1829.[47]

The first ten prints in the series, including The Great Wave, are among the first Japanese prints to feature Prussian blue, which was most likely suggested to the publisher in 1830. This innovation was an immediate success.[29] In the New Year of 1831, Hokusai's publisher, Nishimuraya Yohachi (Eijudō), advertised the innovation everywhere,[47] and the following year Nishimuraya published the next ten prints in the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, all of which are unique in that some of them are printed using the aizuri-e technique: images printed exclusively in blue. One such aizuri-e print is entitled Kōshū Kajikazawa, "Kajikazawa in Kai Province".[48]

The outlines on these ten supplementary prints are sumi black with India ink, rather than the Prussian blue tone. These ten prints are known as ura Fuji, which translates as "Fuji seen from behind."[47]

Prints in the world

About a thousand copies of The Great Wave were initially printed, resulting in wear in later editions of print copies. However, it is estimated that approximately 8,000 copies were printed in total.[b][49] The first signs of wear were the pink and yellow of the sky, which fades more in worn copies, resulting in vanishing clouds and a more uniform sky, and broken lines around the box containing the title.[16][50] Some of the surviving copies have also been damaged by light, as the woodblock prints of the Edo period utilised light sensitive colourants.[49] There are about 100 copies of The Great Wave known to survive today.[c][50][49] Some of these copies can be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York,[51] the Los Angeles County Museum of Art,[52] the British Museum in London,[34] the Giverny Museum of Impressionisms in Giverny, France,[53] the Sackler Gallery in Washington D.C., the Tokyo National Museum,[54] the Japan Ukiyo-e Museum in Matsumoto,[55] the Musée Guimet[29] and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.[56] Some private collections, such as the Gale Collection also have copies of The Great Wave.[16]

Nineteenth-century private collectors were frequently the source of museum collections of Japanese prints: for example, the copy in the Metropolitan Museum comes from Henry Osborne Havemeyer's former collection, which was donated to the museum by his wife in 1929.[57] Similarly, the copy in the Bibliothèque nationale de France came from the collection of Samuel Bing in 1888.[58] The copy in the Musée Guimet is a bequest from Raymond Koechlin, who gave it to the museum in 1932.[59]

-

Copy in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Copy in the The British Museum

-

Copy in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

-

Copy in the Tokyo National Museum

Influence

Western art

Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan ended a long period of national isolation and became open to imports from the West. In turn, much Japanese art came to Europe and America and quickly gained popularity.[53] The influence of Japanese art on Western culture became known as Japonism. Japanese woodblock prints became a source of inspiration for artists in many genres, particularly the Impressionists.[60]

Considered the most famous Japanese print,[19] The Great Wave off Kanagawa influenced great works: in painting, works by Claude Monet, in music,[22] Claude Debussy's La Mer, and in literature, Rainer Maria Rilke's Der Berg.[19][61] Claude Debussy, who loved the sea and painted images of the Far East, kept a copy of The Great Wave in his studio. During his work on La Mer, he was inspired by the work, and he requested that the image be placed on the cover of the original 1905 score.[21][62][63]

Henri Riviére, a draughtsman, engraver, and watercolourist who was also a driving force behind Le Chat Noir, was one of the first artists to be heavily influenced by Hokusai's work, particularly The Great Wave. In homage to Hokusai's work, he published a series of lithographs titled The Thirty-Six Views of the Eiffel Tower in 1902.[64] He was a Japanese print collector who purchased works from Siegfried Bing, Tadamasa Hayashi, and Florine Langweil.[65]

Vincent van Gogh, a great admirer of Hokusai, praised the quality of drawing and use of line in The Great Wave, and said it had a terrifying emotional impact.[66] French sculptor Camille Claudel's La Vague (1897) replaces the boats in Hokusai's The Great Wave with three women dancing in a circle.[67]

In popular culture

The Great Wave is one of the most reproduced and most instantly recognized artworks in the world.[68][69] Hiroshige paid homage to The Great Wave with his The Sea off Satta in Suruga Province,[70] while French artist Gustave-Henri Jossot used a satire painting in the style of The Great Wave to mock the Japanonisme craze.[71] Many modern artists have also reinterpreted and adapted the image. Indigenous Australian artist Lin Onus used The Great Wave as the basis for his 1992 painting Michael and I are just slipping down the pub for a minute.[72] A work named Uprisings by Japanese-American artist Kozyndan is based on the print, with the foam of the wave being replaced by rabbits.[73]

-

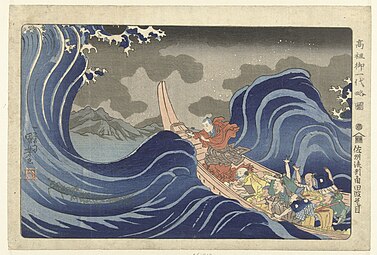

Monk Nichiren Calming the Stormy Sea by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (c. 1835)

-

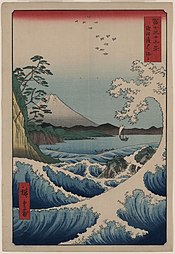

The Sea off Satta in Suruga Province by Hiroshige (1858)

-

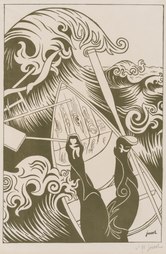

The Wave, lithograph by Gustave-Henri Jossot (1894)

-

Japanese 1,000 yen banknote to be issued in 2024

Media

Special programmes and documentaries have been produced about The Great Wave. In French, there is La menace suspendue: La Vague, a 30-minute documentary from 1995.[74] In English, the BBC aired a special programme as part of the series Private Life of a Masterpiece on 17 April 2004,[75] and the print was also chosen to be part of the series A History of the World in 100 Objects, produced in collaboration with the British Museum. The painting was the 93rd in the series, released on 4 September 2010.[76] A replica of The Great Wave was created for a documentary film about Hokusai made by the British Museum in 2017.[77]

Notes

- ^ Also known as The Great Wave or simply The Wave

- ^ As Capucine Korenberg writes, "The number of impressions made from a given set of woodblocks was generally not recorded but it has been estimated that a publisher had to sell at least 2,000 impressions from a design to make a profit."[49]

- ^ Out of 111 copies of the print found by Korenberg, 26 have no discernible clouds.[49]

References

- ^ a b Penkoff 1964, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Singer 1986, p. 66.

- ^ Penkoff 1964, p. 6.

- ^ Kikuchi & Kenny 1969, p. 31.

- ^ Kobayashi 1997, p. 77.

- ^ Kobayashi 1997, p. 81.

- ^ Salter 2001, p. 11.

- ^ a b Cartwright & Nakamura 2009, p. 120.

- ^ a b "Katsushika Hokusai". El Poder de La Palabra (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ a b Weston 2002, p. 116.

- ^ Weston 2002, p. 117.

- ^ Weston 2002, p. 118.

- ^ Guth 2011, p. 468.

- ^ Weston 2002, p. 120.

- ^ Calza 2003, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Hillier 1970, p. 230.

- ^ a b "Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), also known as The Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Ornes 2014, p. 13245.

- ^ a b c d Cartwright & Nakamura 2009, p. 119.

- ^ Cartwright & Nakamura 2009, pp. 122–123.

- ^ a b c Kobayashi 1997, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cartwright & Nakamura 2009, p. 121.

- ^ a b Cartwright & Nakamura 2009, p. 123.

- ^ Médicis & Huebner 2018, p. 319.

- ^ Dudley 2013, p. 159.

- ^ Bayou 2008, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Honour & Fleming 1991, p. 597, "Mount Fuji's snow covered cone recurs in them, glimpsed in the most famous from the through of a great wave breaking into spray like dragon-claws over fragile boats."

- ^ "HOKUSAI: BEYOND THE GREAT WAVE". Asian Art Newspaper. 1 June 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Hokusai "Mad about his art" from Edmond de Goncourt to Norbert Lagane". Guimet Museum. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010.

- ^ Goncourt 2015, pp. 9, 38.

- ^ ""The Wave" by Hokusai and "The Jingting Mountains in Autumn" by Shitao". CNDP.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 3 October 2009.

- ^ Rüf, Isabelle (29 December 2004). "La "Grande vague" du Japonais Hokusai, symbole de la violence des tsunamis". Le Temps (in French). Archived from the original on 21 October 2008.

- ^ Cartwright & Nakamura 2009, p. 128.

- ^ a b "The Great Wave – print". The British Museum. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Nagata 1995, p. 40.

- ^ a b Delay 2004, p. 197.

- ^ "Hokusai". Yale University. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011.

- ^ Harris 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Calza 2003, p. 484.

- ^ Ives 1974, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Lane 1962, p. 237.

- ^ Delay 2004, p. 173.

- ^ Bayou 2008, p. 110.

- ^ Lane 1962, p. 233.

- ^ Bayou 2008, p. 144.

- ^ Graham, John (September 1999). "Hokusai and Hiroshige: Great Japanese Prints from the James A. Michener Collection at the Asian Art Museum". UCSF Weekly. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009.

- ^ a b c Bayou 2008, p. 130.

- ^ Calza 2003, p. 473.

- ^ a b c d e Korenberg, Capucine. "The making and evolution of Hokusai's Great Wave" (PDF). British Museum. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Under the Wave off Kanagawa". www.hokusai-katsushika.org. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ "The Great Wave at Kanagawa (from a Series of Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ "The Great Wave off Kanagawa". Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Japonism Impressionism Exhibition in Giverny Impressionist Museum 2018". Giverny Museum of Impressionisms. 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "HOKUSAI". Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ "Hokusai: the influential work of Japanese artist famous for 'the great wave' – in pictures". The Guardian. 20 July 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Sous la vague au large de Kanagawa". Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ Forrer 1991, p. 43.

- ^ Bibliothèque nationale de France 2008, p. 216.

- ^ Bayou 2008, p. 131.

- ^ Bickford 1993, p. 1.

- ^ Cirigliano II, Michael (22 July 2014). "Hokusai and Debussy's Evocations of the Sea". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Moore 1979, p. 245.

- ^ Médicis & Huebner 2018, p. 275.

- ^ Sueur-Hermel 2009, p. 28.

- ^ Sueur-Hermel 2009, p. 26.

- ^ "Letter 676: To Theo van Gogh. Arles, Saturday, 8 September 1888". Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ "The Wave or The Bathers". Musée Rodin. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Wood, Patrick (20 July 2017). "Is this the most reproduced artwork in history?". ABC News. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Gamerman, Ellen (18 March 2015). "How Hokusai's 'The Great Wave' Went Viral". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "print". The British Museum. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ "La vague (The Wave), 1894". Minneapolis Institute of Art. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Ashcroft 2013, p. 11.

- ^ "'Uprisings', 2018". www.artsy.net. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ "Hokusai "la menace suspendue" – Documentaire (1995) – SensCritique". senscritique.com (in French). Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "'The Great Wave' by Hokusai". Fulmartv.co.uk. 17 April 2004. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ "BBC – A History of the World – Object : Hokusai's 'The Great Wave'". BBC. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Wheatley, Patricia (2 June 2017). "Hokusai in Ultra HD: Great Wave, big screen". British Museum. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

Sources

- Ashcroft, Bill (26 July 2013). "Hybridity and Transformation: The Art of Lin Onus". Postcolonial Text. 8 (1).

- Bayou, Hélène (2008). Hokusai 1760–1849 – "L'affolé de son art" d'Edmond de Goncourt à Norbert Lagane (in French). Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux. ISBN 978-2-7118-5406-6.

- Bickford, Lawrence (1993). "Ukiyo-e Print History". Impressions (17): 1. JSTOR 42597774.

- Calza, Gian Carlo (2003). Hokusai. London: Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-4304-9.

- Cartwright, Julyan H.E.; Nakamura, Hisami (20 June 2009). "What kind of a wave is Hokusai's Great wave off Kanagawa?". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 63 (2): 119–135. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2007.0039. S2CID 35033146.

- Delay, Nelly (2004). L'estampe japonaise (in French). Paris: F. Hazan. ISBN 2-85025-807-5.

- Dudley, J. M.; Sarano, V.; Dias, F. (2013). "On Hokusai's Great wave off Kanagawa: localization, linearity and a rogue wave in sub-Antarctic waters". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 67 (2): 159–164. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2012.0066. ISSN 0035-9149. PMC 3645210. PMID 24687148.

- Forrer, Matthi (1991). Hokusai: Prints and Drawings. Neues Publishing Company. ISBN 978-3-7913-1131-9.

- Goncourt, Edmond de (15 September 2015). Hokusai. Parkstone International. ASIN B016XN14YS.

- Guth, Christine (2011). "Hokusai's Great Waves in Nineteenth-Century Japanese Visual Culture" (PDF). The Art Bulletin. 93 (4): 468–485. doi:10.1080/00043079.2011.10786019. ISSN 0004-3079. PMID 00043079. S2CID 191470775.

- Harris, James C. (January 2008). "Under the Wave off Kanagawa". JAMA Psychiatry. 65 (1): 12–13. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.21. PMID 18180422. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- Hillier, Jack (1970). Gale Catalogue of Japanese Paintings and Prints in the Collection of Mr. & Mrs. Richard P. Gale. Vol. 2. Routledge. ISBN 9780710069139.

- Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (1991). A World History of Art. Tres Cantos, Madrid: Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 9781856690003.

- Ives, Colta Feller (1974). The Great Wave: the Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-228-5.

- Kikuchi, Sadao; Kenny, Don (1969). A Treasury of Japanese Wood Block Prints (Ukiyo-e). Crown Publishers. OCLC 21250.

- Kobayashi, Tadashi (1997). Harbison, Mark A. (ed.). Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2182-3.

- Lane, Richard (1962). Masters of the Japanese Print, Their World and Their Work. Creative Media Partners, LLC. ISBN 978-1-01-530023-1.

- Médicis, François de; Huebner, Steven, eds. (2018). Debussy's Resonance. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-58046-525-0.

- Moore, Janet Gaylord (1979). The Eastern Gate: An Invitation to the Arts of China and Japan. Collins. ISBN 978-0-529-05434-0.

- Nagata, Seiji (1995). Hokusai: Genius of the Japanese Ukiyo-e. Kodansha. ISBN 978-4-7700-1928-8.

- Ornes, Stephen (2014). "Science and Culture: Dissecting the "Great Wave"". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (37): 13245. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11113245O. doi:10.1073/pnas.1413975111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4169912. PMID 25228754.

- Penkoff, Ronald (1964). Roots of the Ukiyo-e; Early Woodcuts of the Floating World (PDF). Ball State Teachers College. OCLC 681751700.

- Salter, Rebecca (2001). Japanese Woodblock Printing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2553-9.

- Sueur-Hermel, Valérie (2009). Henri Rivière: entre impressionnisme et japonisme (in French). Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France. ISBN 9782717724318.

- Singer, Robert T. (March–April 1986). "Japanese Painting of the Edo Period". Archaeology. 39 (2). Archaeological Institute of America: 64–67. JSTOR 41731745.

- Weston, Mark (2002). Giants of Japan: The Lives of Japan's Greatest Men and Women. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-1-56836-324-0.

External links

Media related to 神奈川沖浪裏 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 神奈川沖浪裏 at Wikimedia Commons- The Metropolitan Museum of Art's (New York) entry on The Great Wave at Kanagawa

- Episode from the BBC show A History of the World in 100 Objects

- Study of original work opposed to various copies from different publishers

- The Great Wave (making the woodblock print) Step-by-step video series on recreating the work by David Bull

- Replica of The Great Wave made by Suga Kayoko for a documentary film by the British Museum