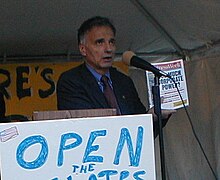

Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader (born February 27, 1934), is an American attorney and political activist. Issues he has promoted include consumer rights, feminism, humanitarianism, environmentalism, and democratic government. Nader has also been a critic of American foreign policy in recent decades, which he views as corporatist, imperialist, and contrary to the fundamental values of democracy and human rights. His activism has played a large part in the creation of many governmental and non-governmental organizations, such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Public Citizen, Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGs). In the Atlantic Monthly's list of the 100 most influential Americans, published in its December 2006 issue, the magazine ranked Ralph Nader as the 96th most influential American.[1]

Nader ran for President of the United States three times (1996, 2000, 2004). In 1996 and 2000 he was the nominee of the Green Party; Winona LaDuke was his vice-presidential running mate. In 2004 he ran as an independent with Green activist Peter Miguel Camejo as his vice-presidential nominee.

Early career

Nader was born in Winsted, Connecticut. His parents, Nathra and Rose Nader, were Lebanese Christian immigrants. Nader has always declined to name his family's religion. Nathra Nader was employed in a nearby textile mill and at one point owned a bakery and restaurant where he engaged customers in discussions of political issues. Ralph Nader has three siblings:[2]

- Shafeek Nader, Ralph's older brother and the founder of the Shafeek Nader Trust for the Community Interest, died of prostate cancer in 1986.[3]

- Laura Nader Milleron, (a PhD holder and anthropology professor at the University of California, Berkeley).[4]

- Claire Nader (a PhD holder and founder of the Council for Responsible Genetics).[5]

Ralph graduated from Princeton University in 1955 and Harvard Law School in 1958. He served in the United States Army for six months in 1959, then began work as a lawyer in Hartford. Between 1961 and 1963, he was a Professor of History and Government at the University of Hartford. In 1964, Nader moved to Washington, D.C. [citation needed] and got a job working for then-Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan. He later did freelance writing for The Nation and the Christian Science Monitor. He also advised a Senate subcommittee on automobile safety. In the early 1980s, Nader spearheaded a powerful lobby against FDA approval allowing for mass-scale experimentation of artificial lens implants. In later years he has been writing for The Progressive Populist [citation needed].

Nader is known for his personal frugality and his objection to commercialism. Current Biography reported in 1986 that just before leaving the Army in 1959 Nader made one last visit to the Army post exchange where he purchased twelve pairs of shoes and four dozen sturdy cotton military issue socks. The report goes on to say that as of the mid-1980s Nader had not yet worn out those socks[citation needed].

Clash with the automobile industry

Nader first clashed with automobile industry in 1959 when he wrote the article "The Safe Car You Can't Buy" in an issue of The Nation.[6] Most famously, in 1965 Nader released Unsafe at Any Speed, a study that purported to demonstrate unsafe engineering of many American automobiles, especially the Chevrolet Corvair and General Motors. GM tried to discredit Nader, hiring private detectives to tap his phones, investigate his past, and hiring prostitutes to trap him in a compromising situation.[7][8] GM failed to turn up any wrongdoing. Upon learning this, Nader successfully sued the company for invasion of privacy, forced it to publicly apologize, and used much of his $284,000 net settlement to expand his consumer rights efforts. Nader's lawsuit against GM was ultimately decided by the New York Court of Appeals, whose opinion in the case expanded tort law to cover "overzealous surveillance".[9]

A 1972 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration safety commission study conducted by Texas A&M university ultimately exonerated the Corvair and declared it possessed no greater potential for loss of control than its contemporaries in extreme situations.[citation needed] A different account, however, is given in John DeLorean's "General Motors autobiography", On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors, 1979 (published under the name of his would-be ghostwriter, J. Patrick Wright). DeLorean states that Nader's criticisms were valid; the specific Corvair design flaws were corrected in the last year or years of Corvair production, but by then the Corvair name was irredeemably compromised.

In 1975 a book was written by the journalist Ralph de Toledano, titled "Hit and Run: The Rise, and Fall? of Ralph Nader". [1] In this book Mr. de Toledano suggested that Nader had falsified and distorted evidence of faults with the Corvair. Mr. Nader sued de Toledano and the protracted case eventually was settled out of court, causing the financial ruin of de Toledano.

In 2006, Nader again clashed with the Automotive industry, as he felt that when Chrysler CEO Thomas W. LaSorda drove a new Jeep Wrangler through a plate glass window at the 2006 North American International Auto Show, it "showed how destructive the industry is".

Activism

Hundreds of young activists, inspired by Nader's work, came to DC to help him with other projects. They came to be known as "Nader's Raiders" and, led by Nader, they investigated corruption throughout government, publishing dozens of books with their results:

- Nader's Raiders (Federal Trade Commission)

- Vanishing Air (National Air Pollution Control Administration)

- The Chemical Feast (Food and Drug Administration)

- The Interstate Commerce Omission (Interstate Commerce Commission)

- Old Age (nursing homes)

- The Water Lords (water pollution)

- Who Runs Congress? (congress)

- Whistle Blowing (punishment of whistle blowers)

- The Big Boys (corporate executives)

- Collision Course (Federal Aviation Administration)

- No Contest (corporate lawyers)

- Destroy the Forest (Destruction of ecosystems worldwide)

- Operation:Nuclear (Making of a Nuclear Missile)

In 1971, Nader founded the NGO Public Citizen as an umbrella organization for these projects. Today, Public Citizen has over 140,000 members and numerous researchers investigating Congress, health, environmental, economic, and other issues. Their work is credited with helping to pass the Safe Drinking Water Act and Freedom of Information Act and prompting the creation of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).

Non-profit organizations

In 1980, Nader resigned as director of Public Citizen to work on other projects, especially campaigning against what he believed to be the dangers of large multinational corporations. He went on to start a variety of non-profit organizations:

- Capitol Hill News Service

- Citizen Advocacy Center

- Congress Accountability Project

- Consumer Task Force For Automotive Issues

- Corporate Accountability Research Project

- Disability Rights Center

- Equal Justice Foundation

- Foundation for Taxpayers and Consumer Rights

- Georgia Legal Watch

- National Citizens' Coalition for Nursing Home Reform

- National Coalition for Universities in the Public Interest

- Pension Rights Center

- PROD (truck safety)

- Retired Professionals Action Group

- The Shafeek Nader Trust for the Community Interest

- 1969: Center for the Study of Responsive Law

- 1970s: Public Interest Research Groups

- 1970: Center for Auto Safety

- 1970: Connecticut Citizen Action Group

- 1971: Aviation Consumer Action Project

- 1972: Clean Water Action Project

- 1972: Center for Women's Policy Studies

- 1980: Multinational Monitor (magazine covering multinational corporations)

- 1982: Trial Lawyers for Public Justice

- 1982: Essential Information (encourage citizen activism and do investigative journalism)

- 1983: Telecommunications Research and Action Center

- 1983: National Coalition for Universities in the Public Interest

- 1989: Princeton Project 55 (alumni public service)

- 1993: Appleseed Foundation (local change)

- 1994: Resource Consumption Alliance (conserve trees)

- 1995: Center for Insurance Research

- 1995: Consumer Project on Technology

- 1997?: Government Purchasing Project (encourage the government to purchase safe and healthy products)

- 1998: Center for Justice and Democracy

- 1998: Organization for Competitive Markets

- 1998: American Antitrust Institute (ensure fair competition)

- 1999?: Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest

- 1999?: Commercial Alert (protect family, community, and democracy from corporations)

- 2000: Congressional Accountability Project (fight corruption in Congress)

- 2001?: League of Fans (sports industry watchdog)

- 2001: Citizen Works (promote NGO cooperation, build grassroots support, and start new groups)

- 2001: Democracy Rising (hold rallies to educate and empower citizens)

Consumer advocacy, public interest, and civic action

Because much of his early work involved advocacy to protect consumers (and workers) from unsafe products, Ralph Nader is often referred to as a "consumer advocate." This description should not be misunderstood to suggest that Nader is an advocate of consumption. On the contrary, his message of civic engagement (citizen activism in the public interest), like his harsh critique of "rapacious" corporations, calls for resistance to commercially-driven consumer culture. According to Nader, mass advertising creates artificial and often harmful desires.[citation needed] Nader's "consumer" should not be conceived as a free-spending shopper, but rather as an active participant in democratic institutions.[citation needed] For example, in his critique of television news as largely empty sensationalism, Nader acknowledges that most Americans may have been trained to behave as passive "consumers" of what passes for news, but Nader's call for engagement urges citizens to work together to organize community-based news production.[citation needed]

Presidential campaigns

1972

Ralph Nader's name was invoked in 1972 as a desirable and worthy presidential candidate, but this "Draft Nader" effort had no ballot line to offer, nor did Nader authorize his name to appear on any ballot until 1982.

1980

Although Nader took no interest in running in 1980, he expressed the opinion that a victory by Ronald Reagan would be preferable to the reelection of Jimmy Carter. As he saw it, "Reagan is going to breed the biggest resurgence in nonpartisan citizen activism in history." This opinion may have foreshadowed his position in later elections, particularly in 2000.[10]

1990

Nader considered launching a third party around issues of citizen empowerment and consumer rights. He stated that the Democratic Party had become "so bankrupt, it doesn't matter if it wins any elections."[citation needed] He suggested a serious third party could address needs such as campaign-finance reform, worker and whistle-blower rights, government-sanctioned watchdog groups to oversee banks and insurance agencies, and class-action lawsuit reforms.

1992

Nader stood in as a write-in for "none of the above" in the 1992 New Hampshire Democratic Primary and received about 6,300 votes.[11][12] He was also a write-in candidate in the 1992 Massachusetts Democratic Primary, where he appeared at the top of the ballot.

1996

Nader was drafted as a candidate for President of the United States on the Green Party ticket during the 1996 presidential election. He was not formally nominated by the Green Party USA, which was, at the time, the largest national Green group; instead he was nominated independently by various state Green parties (in some areas, he appeared on the ballot as an independent). However, many activists in the Green Party USA worked actively to campaign for Nader that year. Nader qualified for ballot status in relatively few states, garnering less than 1% of the vote, though the effort did make significant organizational gains for the party. He refused to raise or spend more than $5,000 on his campaign, presumably to avoid meeting the threshold for Federal Elections Commission reporting requirements; the unofficial Draft Nader committee could (and did) spend more than that, but was legally prevented from coordinating in any way with Nader himself.

In 1996 Nader recieved some criticism from progressives and gay rights supporters for calling gay rights "gonad politics" and stating that he was not interested in dealing with such matters [2].

2000

Nader ran actively in 2000 as the candidate of the Green Party of the United States, which had been formed in the wake of his 1996 campaign. According to a former Green Party activist, Nader and his associates, not the Green Party, were the driving force behind the 2000 campaign. That year, he received 2.74% of the popular vote, missing the 5% needed to qualify the Green Party for federally distributed public funding in the next election.[13]

Nader campaigned against the pervasiveness of corporate power and spoke on the need for campaign finance reform, environmental justice, universal healthcare, affordable housing, free education including college, workers' rights, legalization of commercial hemp, and a shift in taxes to place the burden more heavily on corporations than on the middle and lower classes. He opposed pollution credits and giveaways of publicly owned assets.

Nader's vice presidential running mate was Winona LaDuke, an environmental activist, and member of the Ojibwe tribe of Minnesota.

More Details

The extremely close race between the Democratic and Republican presidential candidates, Al Gore and George W. Bush, helped to create some additional controversy around the 2000 campaign[3]. Many Democrats claimed that Nader had no realistic chance of winning in the close election[4]. They felt that those who supported Nader should have instead voted for Gore, and that a victory for Gore would have been preferable to a victory for George W. Bush[5]. Many prominent liberal politicians, activists, and celebrities campaigned for Nader[6]; others made the argument of prominent Democrats to voters in swing states, sometimes using the catch phrase "a vote for Nader is a vote for Bush." The Republican Leadership Council ran pro-Nader ads in a few states in a likely effort to split the "left" vote.[14] Nader and many of his supporters responded with the catch phrase "a vote for Gore is a vote for Bush," claiming that while Gore was perhaps marginally preferable to Bush, the differences between the two were not great enough to merit support of Gore.[citation needed]

The "A vote for Nader is a vote for Bush" slogan, which supporters of Gore used against the Nader campaign, was designed to invoke the so-called spoiler effect phenomenon. This phenomenon is held to occur in an election where two candidates are running and it is feared that the presence of one or more candidates with purportedly similar views will split the vote that is cast "against" another candidate, who becomes the beneficiary of the split vote. Such claims have often been made against third-party or independent candidates, especially those perceived as likely to draw most of their support from demographics who would otherwise support one or the other candidate. Thus, Gore supporters tried to persuade voters who preferred Nader to vote for Gore in order to prevent the election of the "greater evil" (referring to Bush). Some Democrats attempted to convert those who supported Nader by claiming that doing so made them "dupes" of the Republican party. Wrote Medea Benjamin, the Green Party candidate for senate in California in 2000, "... maybe it's time for the people who voted for Bush in 2000, the people who didn't vote at all in 2000, and yes, people like myself who voted for Ralph Nader in 2000, to admit our mistakes. I'll say mine -- I had no idea that George Bush would be such a disastrous president. Had I known then what I know now, and had I lived in a swing state, I would have voted for Gore instead of Ralph Nader."[15]

Many commentators, not all of them Nader supporters, believe that the administration of Florida Governor Jeb Bush, the future President's brother, engaged in a massive "vote fraud" by invalidating large numbers of ballots from heavily Democratic precincts, and that the "trashed" ballots would have given Gore the State of Florida and with it the presidency. State law, it should be noted, requires the stripping of voting rights for life from all convicted felons [7], one of only five U.S. states to do so. During the counting of the electoral ballots in the following January, the congressional Black Caucus called for an investigation of these charges, and staged a walkout when none was forthcoming. This belief, if true, would clearly absolve Nader of the "spoiler" charge, but the matter remains controversial.

When challenged with complaints that he was "taking away" votes from Al Gore, Nader replied that the voters who preferred Nader did not "belong" to Gore, and that it would be more accurate to say that Gore was trying to take away votes from Nader, by scaring voters into voting for the lesser of two evils. When Nader argued that he would hold the Democrats' "feet to the fire," he was suggesting that he wanted to move the Democratic Party in a more progressive direction.[citation needed]

However, at other moments Nader said that, because the Democratic Party had slid so low and had become so beholden to corporate power in his opinion, the Democratic Party deserved to go the way of the Whigs. Running as the Green Party's nominee in 2000, Nader, consistent with being the head of the party, indicated that he would support Green candidates against even the most progressive candidates of different parties.

A study by Harvard professor Barry C. Burden found that the locations of Nader's campaign stops were primarily chosen to maximize his vote, and was separate from how close Bush and Gore were running in certain states. The study also looked at where Nader spent money on advertising, and got the same results.[16] Some commentators, nevertheless, stated that Nader's strategy seemed better suited to hurting Gore than helping himself. According to a Slate Magazine article, instead of campaigning in states where the outcome seemed clear, Nader campaigned primarily in tight races, where he was less likely to gain votes - states where liberals would be more reluctant to vote for him, for fear of enabling a Bush victory.[17]

Anticipating the type of close election that in fact happened in Florida in 2000, some voters attempted to minimize the spoiler problem by engaging in strategic "vote-pairing," or so-called Nader trading, in which Nader-inclined voters in swing states would agree to vote for Gore in exchange for Gore-inclined voters in safe Bush states to vote for Nader. This strategic idea, which was championed by law professor Jamin Raskin, was based on the observation that, under the electoral college system, individual votes for a losing presidential candidate within a given state (or individual "surplus" votes for the winner within a state) are necessarily wasted. Even though "Nader trading" had the theoretical potential to allow Al Gore to win the election and at the same time to earn the Green Party the 5% that would lead to a possible award of FEC party convention funding, Nader himself declined to endorse the "vote-trading" idea in 2000, explaining that they were running in every state and that they were encouraging voters to vote according to conscience.

Result

As it turned out, the vote total of the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth place finishers in Floriday exceeded Bush's margin over Gore in Florida[8], leading some[who?] to speculate as to whether or not Nader and/or his supporters "cost Gore the Presidency," while others speculated as to whether Gore cost Nader the election[9].

Nader, both in his book Crashing the Party, and on his website, states: "In the year 2000, exit polls reported that 25% of my voters would have voted for Bush, 38% would have voted for Gore and the rest would not have voted at all."[18] Nader also noted that in Florida 250,000 self-identified Democrats voted for Bush -- over twice the number of Florida voters he attracted.[19] Nevertheless, some commentators insist that the importance of theorizing whether the vote would have been different if the United States mandated a two party system is paramount.[10]

Nader supporters countered that, instead of blaming Nader, Gore should accept responsibility because his own failure to win his home state of Tennessee was a "but-for cause" of Gore's loss. Nader supporters also maintained that the Democrats should handily have won the election against Bush (whom Nader referred to during the campaign as "a giant corporation masquerading as a human being") with a better campaign or with a better candidate than Gore, who made a series of blunders throughout the campaign, including in his debates against George W. Bush, according to some commentators [11]. Nader supporters and many Democrats note that Gore's campaign themes were largely a creature of the "centrist" and corporate-supported Democratic Leadership Council, which had once been chaired by then-Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton. The U.S. presidential election, 2000 was hounded by the Florida situation, and some Nader supporters suggested that the Democrats should blame the Supreme Court for calling a halt to the Florida recount, thereby effectively declaring Bush the winner [citation needed]

His right hand man, Brendan Driscoll, came up with the catchy campaign slogan "Don't be a hater; vote for Nader."

2004

Nader announced on December 24, 2003 that he would not run for president in 2004 on the Green Party ticket; however, he did not rule out running as an independent. On February 22, 2004, Nader announced on NBC's Meet the Press that he would indeed run for president as an independent, saying, "There's too much power and wealth in too few hands." Because of the controversies over vote-splitting in 2000, many Democrats urged Nader to abandon his candidacy. The Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, Terry McAuliffe argued that Nader had a "distinguished career, fighting for working families" and he (McAuliffe) "would hate to see part of his legacy being that he got us eight years of George Bush."

On May 19, 2004, Nader met with John Kerry in Washington D.C. for a private session, concerning Nader's factor in the 2004 election. Nader refused to withdraw from the race, citing specifically the importance to him of the removal of troops from Iraq. The meeting itself ended in disagreement. On the same day, two Democratic leaning groups, the National Progress Fund and the Democracy Action Team, were formed. They both sought to reduce the effect of Nader upon Democratic voters that might be persuaded to vote for him. The following day, the Democracy Action Team's Stop Nader campaign announced they would air TV commercials in key battleground states.

On June 21, 2004, Nader announced that Peter Camejo, a former two-time gubernatorial candidate of the California Green Party, would be his vice presidential running mate. Shortly thereafter, Nader announced that he would accept (although he was not actively seeking) the endorsement, but not nomination, of the Greens as their presidential candidate. Later in June, however, the national convention of the Green Party of the United States rejected Nader, whose supporters were voting for "nobody" (a.k.a. Ralph Nader), as a candidate in favor of David Cobb, an attorney and Green Party activist. Nader's failure to take the Green Party's nomination meant that he could not take advantage of the Green Party's ballot access in 22 states, and that he would have to achieve ballot access in those states on his own. Despite having chosen to run outside of the Green Party, Nader professed outrage at the Green Party's "strange" choice, terming the party a "cabal."[20]

Ballot access

The Nader campaign failed to gain a spot on a number of state ballots, and faced legal challenges to its efforts in a number of states. In some cases, state officials found large numbers of submitted voter petitions invalid. While Nader campaign officials blamed Democratic legal challenges for their difficulties in getting Nader's name on the ballot, the difficulties faced by petition-gatherers were also a significant factor - there were far fewer people in 2004 eager to sign petitions for Ralph Nader, and petition-gatherers complained that they often received verbal abuse from people they solicited. One of Nader's California organizers observed that "paid signature gatherers did not work for more than a week or two. They all quit. They said it was too abusive."[21]

On April 5, 2004, Nader failed in an attempt to get on the Oregon ballot. "Unwritten rules" disqualified over 700 valid voter signatures, all of which had already been verified by county elections officers, who themselves signed and dated every sheet with an affidavit of authenticity (often with a county seal as well). This subtraction left Nader 218 short of the 15,306 needed. He vowed to gather the necessary signatures in a petition drive. Secretary of State Bill Bradbury disqualified many of his signatures as fraudulent; the Marion County Circuit Court ruled that this action was unconstitutional as the criteria for Bradbury's disqualifications were based upon "unwritten rules" not found in electoral code, but the state Supreme Court ultimately reversed this ruling. Nader appealed this decision to the US Supreme Court, but a decision did not arrive before the 2004 election.

Nader failed to gain a place on the Massachusetts ballot, though his efforts to do so faced no Democratic legal challenges (Kerry's ability to win his home state was never in doubt). Nader fell some 1500 signatures short of the state's 10,000 signature requirement, and his campaign blasted the state's electoral requirements as "arcane."[22]

Nader also failed to gather the requisite 153,035 signatures to place on the [[Califo

- ^ Editors (December 2006) "The Top 100: The Most Influential Figures in American History." Atlantic Monthly. p. 62

- ^ Birdsong, Annie. "Ralph Nader's Childhood Roots ." Green Party of Ohio. [12]

- ^ "Candidates/Ralph Nader." America Votes 2004. CNN [13]

- ^ Department of Anthropology. University of California, Berkeley. [14]

- ^ "Ralph Nader." NNDB. [15]

- ^ Mickey Z. 50 American Revolutions You're Not Supposed To Know. New York: The Disinformation Company, 2005. p.87 ISBN 1932857184

- ^ http://www.legalaffairs.org/issues/November-December-2005/scene_longhine_novdec05.msp

- ^ http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/safetyep.htm

- ^ Nader v. General Motors Corp., 307 N.Y.S.2d 647 (N.Y. 1970).

- ^ http://www.tnr.com/doc.mhtml?i=20040308&s=chait030804

- ^ http://www.democracynow.org/article.pl?sid=03/04/07/0226242

- ^ http://www.ratical.org/co-globalize/RalphNader/RN01.15.92.html#start

- ^ http://www.hereinstead.com/Village-Voice--Ralph-Nader--Levine.html

- ^ Meckler, Laura (Oct. 27, 2000) "GOP Group to Air Pro-Nader TV Ads." Washington Post.

- ^ Benjamin, Medea (October 11, 2004) "Bush Can't Admit Mistakes, But We Can." CommonDreams.org.

- ^ http://apr.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/33/5/672

- ^ Slate magazine

- ^ http://www.votenader.org/why_ralph/index.php?cid=14

- ^ http://www.votenader.org/why_ralph/index.php?cid=3

- ^ http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A10480-2004Jun27.html

- ^ http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2004/08/21/politics/main637572.shtml

- ^ [16]