Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604)

| Anglo-Spanish War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War and the Anglo-Spanish Wars | |||||||

English ships and the Spanish Armada, 8 August 1588, unknown artist | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | 105,800 English soldiers and sailors (1588–1603)[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | 88,285 English dead[3] | ||||||

| Wars of Tudor England |

|---|

|

The Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) was an intermittent conflict between the Habsburg Kingdom of Spain and the Kingdom of England. It was never formally declared.[4] The war included much English privateering against Spanish ships, and several widely separated battles. It began with England's military expedition in 1585 to what was then the Spanish Netherlands under the command of the Earl of Leicester, in support of the Dutch rebellion against Spanish Habsburg rule.

The Spanish enjoyed a victory at Grave and Zutphen in 1586, and then a victory at Sluis in 1587. The English enjoyed a victory at Cádiz in 1587, and repelled the Spanish Armada in 1588, but then suffered heavy setbacks: the English Armada (1589), the Drake–Hawkins expedition (1595), and the Essex–Raleigh expedition (1597). In 1596 Spain captures Hulst and England captures captures Cádiz. Spain sent three further armadas against England and Ireland; in 1596, 1597, and 1601,[5] but these ended in failure, mainly because of adverse weather.[3]

The war became deadlocked around the turn of the 17th century during campaigns in the Netherlands, France, and Ireland. It was brought to an end with the Treaty of London (1604), negotiated between Philip III of Spain and the new king of England, James I. In the treaty, England and Spain restored the status quo ante bellum, agreed to cease their military interventions in the Netherlands and Ireland respectively, and resumed trade; the English ended their high seas privateering and the Spanish recognized James as king.[6][7]

Causes

In the 1560s, Philip II of Spain was faced with increasing religious disturbances as Protestantism gained adherents in his domains in the Low Countries. As a defender of the Catholic Church, he sought to suppress the rising Protestant movement in his territories, which eventually exploded into open rebellion in 1566. Meanwhile, relations with the regime of Elizabeth I of England continued to deteriorate, following her restoration of royal supremacy over the Church of England through the Act of Supremacy in 1559; this had been first instituted by her father Henry VIII and rescinded by her sister Mary I, Philip's wife. The Act was considered by Catholics as a usurpation of papal authority. Calls by leading English Protestants to support the Protestant Dutch rebels against Philip increased tensions further as did the Catholic-Protestant disturbances in France, which saw both sides supporting the opposing French factions.

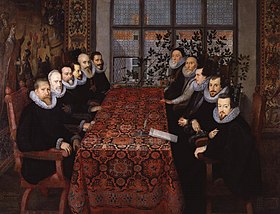

| Opposing monarchs |

|---|

Complicating matters were commercial disputes. The activities of English sailors, begun by Sir John Hawkins in 1562, gained the tacit support of Elizabeth, even though the Spanish government complained that Hawkins's trade with their colonies in the West Indies constituted smuggling. In September 1568, a slaving expedition led by Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake was surprised by the Spanish, and several ships were captured or sunk at the Battle of San Juan de Ulúa near Veracruz in New Spain. This engagement soured Anglo-Spanish relations and in the following year the English detained several treasure ships sent by the Spanish to supply their army in the Netherlands. Drake and Hawkins intensified their privateering as a way to break the Spanish monopoly on Atlantic trade. Francis Drake went on a privateering voyage where he eventually circumnavigated the globe between 1577 and 1580. Spanish colonial ports were plundered and a number of ships were captured including the treasure galleon Nuestra Señora de la Concepción. When news of his exploits reached Europe, Elizabeth's relations with Philip continued to deteriorate.

Soon after the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580, English support was provided to António, Prior of Crato who then fought in his struggle with Philip II for the Portuguese throne. Philip in return began to support the Catholic rebellion in Ireland against Elizabeth's religious reforms. Both Philip's and Elizabeth's attempts to support opposing factions were defeated.

In 1584, Philip signed the Treaty of Joinville with the Catholic League of France to defeat the Huguenot forces in the French Wars of Religion. In the Spanish Netherlands, England had secretly supported the side of the Dutch Protestant United Provinces, who were fighting for independence from Spain. In 1584, the Prince of Orange had been assassinated, leaving a sense of alarm as well as a political vacuum. The following year was a further blow to the Dutch with the capture of Antwerp by Spanish forces led by Alexander Farnese, the Duke of Parma. The Dutch rebels sought help from England, which Elizabeth agreed to as she feared that a Spanish reconquest there would threaten England.[8] The Treaty of Nonsuch was signed as a result – Elizabeth agreed to provide the Dutch with men, horses, and subsidies but she declined overall sovereignty. In return, the Dutch handed over four Cautionary Towns which were garrisoned by English troops. Philip took this to be an open declaration of war against his rule in the Netherlands.

War

The Anglo-Spanish War broke out in 1585, following the seizure of English merchant ships in Spanish harbors. In response the English privy council immediately authorised a campaign against the Spanish fishing industry in Newfoundland and off the Grand Banks.[9] The campaign was a huge success, and subsequently led to England's first sustained activity in the Americas.[10] In August, England joined the Eighty Years' War on the side of the Dutch Protestant United Provinces, which had declared their independence from Spain. In that same year, the English established their first New World settlement, the short lived Roanoke Colony established by Ralph Lane.

The Queen through Francis Walsingham ordered Sir Francis Drake to lead an expedition to attack the Spanish New World in a kind of preemptive strike. Drake sailed in October to the West Indies, and in January 1586 captured and sacked Santo Domingo. The following month they did the same at Cartagena de Indias and in May sailed North to raid St. Augustine in Florida. When Drake arrived in England in July he became a national hero. In Spain however, the news was a disaster and this now further buoyed a Spanish invasion of England by King Philip.[11] Thomas Cavendish meanwhile set out with three ships on 21 July 1586 to raid Spanish settlements in South America. Cavendish raided three Spanish settlements and captured or burned thirteen ships. Among these was a rich 600 ton treasure galleon Santa Ana, the biggest treasure haul that ever fell into English hands. Cavendish circumnavigated the globe returning to England on 9 September 1588.[12]

Dutch Revolt (1585–1587)

Robert Dudley, The Earl of Leicester was sent to the United Provinces in 1585 with a dignitary party and took the offered governorship of the United Provinces. This, however, was met with fury from Elizabeth, who had expressed no desire for any sovereignty over the Dutch. An English mercenary army had been present since the beginning of the war and was then under the command of veteran Sir John Norreys. They combined forces but were undermanned and under-financed, and faced one of the most powerful armies in Europe led by the famed Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma.[13]

During the siege of Grave the following year, Dudley attempted its relief, but the Dutch garrison commander Hadewij van Hemert surrendered the town to the Spanish. Dudley was furious on hearing of Grave's sudden loss and had van Hemert executed, which shocked the Dutch.[14] The English force then had some successes, taking Axel in July and Doesburg the following month. Dudley's poor diplomacy with the Dutch, however, made matters worse. His political base weakened and so too did the military situation.[15] Outside Zutphen an English force was defeated and notable poet Philip Sidney mortally wounded, which was a huge blow to English morale. Zutphen itself and Deventer were betrayed by Catholic turncoats William Stanley and Rowland York, which further damaged Leicester's reputation. Finally Sluis with a largely English garrison was besieged and taken by the Duke of Parma in June 1587, after the Dutch refused to help in the relief. This resulted in mutual recriminations between Leicester and the States.[16]

Leicester soon realised how dire his situation was and asked to be recalled. He resigned his post as governor – his tenure had been a military and political failure, and as a result, he was financially ruined.[17] After Leicester's departure, the Dutch elected the Prince of Orange's son Count Maurice of Nassau as the stadtholder and governor. At the same time Peregrine Bertie took over English forces in the Netherlands.

Spanish Armada

On 8 February 1587, the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots outraged Catholics in Europe. In retaliation for the execution of Mary, Philip vowed to invade England to place a Catholic monarch on its throne. In April 1587 Philip's preparations suffered a setback when Francis Drake burned 37 Spanish ships in the harbour of Cádiz, and as a result the invasion of England had to be postponed for over a year.

On 29 July, Philip obtained Papal authority to overthrow Elizabeth, who had been excommunicated by Pope Pius V, and place whomever he chose on the throne of England. He assembled a fleet of about 130 ships, containing 8,050 sailors, 18,973 soldiers, and 2,088 rowers. To finance this endeavour, Pope Sixtus V had permitted Philip to collect crusade taxes. Sixtus had promised a further subsidy to the Spanish should they reach English soil.[18]

On 28 May 1588, the Armada, under the command of the Duke of Medina Sidonia, set sail for the Netherlands, where it was to pick up additional troops for the invasion of England. As the armada sailed through the English Channel, the English navy, led by Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham, and Francis Drake, fought a battle of attrition with the Spanish from Plymouth to Portland and then to the Solent, preventing them from securing any English harbours.[19] The Spanish were forced to withdraw to Calais. While the Spanish were at anchor there in a crescent-shaped defensive formation, the English used fireships to break the formation and scatter the Spanish ships. In the subsequent Battle of Gravelines the English navy attacked the Armada and forced it to sail northward in more dangerous stormy waters on the long way home. As they sailed around Scotland, the Armada suffered severe damage and loss of life from stormy weather. As they approached the West coast of Ireland more damaging stormy conditions forced ships ashore while others were wrecked. Disease took a heavy toll as the fleet finally limped back to port.[20]

Philip's invasion plans had miscarried partly because of unfortunate weather and his own mismanagement, and partly because the opportunistic defensive naval efforts of the English and their Dutch allies prevailed. The failure of the Armada provided valuable seafaring experience for English oceanic mariners. While the English were able to persist in their privateering against the Spanish and continue sending troops to assist Philip II's enemies in the Netherlands and France, these efforts brought few tangible rewards.[21] One of the most important effects of the event was that the Armada's failure was seen as a sign that God supported the Protestant Reformation in England. One of the medals struck to celebrate the English victory bore the Latin/Hebrew inscription Flavit יהוה et dissipati sunt (literally: "Yahweh blew and they were scattered"; traditionally translated more freely as: "He blew with His winds, and they were scattered").

-

The flagship of the Duke of Medina Sidonia: the San Martin is attacked off the coast of Dover from port side by the English Rainbow and from starboard by the Dutch Gouden Leeuw, Dover, 8 August 1588

English Armada

An English counter armada under the command of Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Norris was prepared in 1589 with three tasks:

- Destroy the battered Spanish Atlantic fleet, which was being repaired in Santander, A Coruña, and San Sebastián in northern Spain.

- Make a landing at Lisbon, Portugal and raise a revolt there against King Philip II (Philip I of Portugal) installing the pretender Dom António, Prior of Crato to the Portuguese throne.

- Take the Azores if possible so as to establish a permanent base and capture the incoming Spanish treasure fleet.

Because this mission was floated as a joint stock company, Drake had investors to satisfy, so, rather than adhere to the Queen's orders, he bypassed Santander in favor of seeking plunder, booty and financial rewards. He started by making a surprise landing at Coruña on 4 May where the lower town was captured and plundered, and a number of merchant ships were seized. Norris then won a modest victory over a Spanish relief militia force at Puente del Burgo. When the English pressed the attack on the citadel, however, they were repulsed with heavy casualties. In addition, a number of English ships were captured by Spanish naval forces.

Two-weeks later, having failed to capture Coruña, the English departed and sailed towards Lisbon landing on 26 May, but owing to poor organisation (they had very few siege guns), lack of co-ordination and starvation the invading force also failed to take Lisbon. The expected uprising by the Portuguese loyal to Crato never materialized. With Portuguese and Spanish reinforcements arriving the English were forced to retreat and sailed North, tossing the dead overboard by the hundred along the way, where Drake sacked and burned Vigo. Young William Fenner who had come from England with 17 supply ships commanded by Captain Cross was separated from the fleet after a storm and found himself heading toward the archipelago of Madeira, ultimately anchoring in Porto Santo where, the next day, seven more English vessels joined him. They took the island and resupplied themselves over the next two days. Unable to find the rest of the fleet, they set sail for England.[23] Drake attempted to sail towards the Azores but could not tack against the prevailing wind. In the face of increasing sickness and deaths, he abandoned the venture and limped back to Plymouth with Captain Diego de Aramburu's flotilla of zabras harassing him nearly the entire way.[24][25]

None of the objectives were achieved[26][27][28][29] and the opportunity to strike a decisive blow against the weakened Spanish navy was lost. The expedition depleted the financial resources of England's treasury, which had been carefully restored during the long reign of Elizabeth I, and its failure was so embarrassing that, even today, England barely acknowledges it ever happened.[26] Through this lost opportunity, Philip was able to revive his navy the very next year, sending 37 ships with 6,420 men to Brittany where they established a base of operations on the Blavet river. The English and Dutch ultimately failed to disrupt the various fleets of the Indies despite the great number of military personnel mobilized every year. Thus, Spain remained the predominant power in Europe for several decades.[30]

Dutch Revolt (1588–1598)

Soon after the defeat of the Armada, the Duke of Parma's force stood down from the invasion. In the autumn Parma moved his force North towards Bergen op Zoom and then attempted to besiege the English-held town with a substantial force. The English in a ruse however managed to repel the Spanish and forced Parma's retreat with heavy losses which boosted both Dutch and English morale.[31] The following year Bertie, under orders from Elizabeth I, left for France with a force to help the Protestants in their fight against the Catholic League. Sir Francis Vere assumed command of English forces thereafter – a position he retained during fifteen campaigns, with almost unbroken success.[32]

In 1590 an Anglo-Dutch force under Maurice and Vere respectively launched a campaign with the aim of taking Breda. In a remarkable feat, a small assault force hid in a peat barge before a successful surprise assault that captured the city. With Spanish forces in France supporting the Catholic League as well as in the Low Countries, Maurice was able to take advantage, and thus started a gradual reconquest of the Netherlands, which became known by the Dutch as the "Ten Glorious Years". Soon after Breda the Anglo-Dutch retook Zutphen and Deventer which restored English prestige after their earlier betrayals. After defeating the Spanish under the Duke of Parma at Knodsenberg in 1591 a new confidence in the army took shape. English troops by this time composed nearly half of the Dutch army. The reconquest continued with Hulst, Nijmegen, Geertruidenberg, Steenwijk, and Coevorden all being taken within the next two years.[32] In 1593 a Spanish attempt led by Francisco Verdugo to recapture Coevorden ended in failure when the Anglo-Dutch under Maurice and Vere relieved the place during the spring of 1594. Finally, the capture of Groningen in the summer of 1594 resulted in the Spanish army being forced out of the northern provinces which led to the complete restoration of the seven provinces.[33]

After these successes, Elizabeth could view the high confidence in the army and renewed the treaty with the States in 1595. English troops having been given high praise by the Dutch were kept at around 4,000 men. They were to be paid for by the States and the Queen would also be repaid on the Crown's expenses in instalments until a conclusion of peace was made.

In 1595, Maurice's campaign was resumed to retake the cities of the Twente region from the Spanish. This was delayed after Huy was besieged in March but Maurice was unable to prevent its fall. When Maurice did go on the offensive an attempt to take Grol in July ended in failure when a Spanish force under 90-year-old veteran Cristóbal de Mondragón relieved the city. Maurice then tried to make an attempt on the city of Rheinberg in September but Mondragon defeated this move at the Battle of the Lippe. Maurice was then forced to cancel further planned offensives as the bulk of his English and Scots troops were withdrawn to take part in the attack on Cadiz. Under their new commander, the Archduke of Austria, the Spanish took advantage of this lull and recaptured Hulst the following year which led to a prolonged stalemate in the campaign and delayed the reconquest.[31]

By 1597, Spanish bankruptcy and the war in France gave the Anglo-Dutch an advantage. At the Battle of Turnhout a Spanish force was surprised and routed; Vere and the Earl of Leicester particularly distinguished themselves. With the Spanish distracted by the siege of Amiens in France, Maurice launched an offensive in the summer. This time both Rhienberg and Greonlo were taken by the Dutch. This was followed by the capture of Bredevoort, Enschede, Ootsmarsum, Oldenzaal, and finally Lingen by the end of the year. The offensive's success meant that most of the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands had been recaptured by the Dutch Republic and a significant barrier had been created along the Rhine river.[34]

Naval war and privateering

In November, 1588, Philip II ordered the construction of 21 new galleons, all of them large.[35] 12 of them were built in Cantabrian ports and stood out due to their number and the names they received; they were known as "the twelve apostles".[36] In addition, 6 were made in Portugal, 2 in Gibraltar and 1 in Vinaroz; all of them entered service in a very short space of time. Philip then established a naval base in Brittany which threatened England and allowed for a sophisticated convoy system and improved intelligence network which frustrated English naval attempts on the Spanish treasure fleet during the 1590s. This was best demonstrated by the repulse of the squadron that was led by Effingham in 1591 near the Azores, who had intended to ambush the treasure fleet. It was in this battle that the Spanish captured the English flagship, the HMS Revenge, after a stubborn resistance by its captain, Sir Richard Grenville. Throughout the 1590s, enormous convoy escorts enabled the Spanish to ship three times as much silver as in the previous decade.

English merchant privateers or corsairs known as Elizabeth's "Sea Dogs" enjoyed more qualified success, however.[37] In the three years after the Spanish Armada was defeated, more than 300 prizes were taken from the Spanish with a declared total value of well over £400,000.[38] English courtiers provided money for their own expeditions as well as others, and even Elizabeth herself would make investments. The Earl of Cumberland made a number of expeditions and a few did yield profit – his first being the Azores Voyage in 1589. Others failed however due to bad weather and his 1591 voyage ended in defeat with Spanish galleys off Berlengas. Cumberland with Sir Walter Raleigh and Martin Frobisher combined financial strength and force that led to the most successful English naval expedition of the war. Off Flores island in 1592, the English fleet captured a large Portuguese carrack, the Madre de Deus, and outwitted a Spanish fleet led by Alonso de Bazán. The expedition's reward equalled nearly half the size of the Kingdom of England's royal annual revenue and yielded Elizabeth a 20-fold return on her investment.[39] These riches gave the English an excited enthusiasm to engage in this opulent commerce.[40] Raleigh himself in 1595 went on an expedition to explore the Orinoco river in an attempt to find the mythical city of El Dorado; in the process the English plundered the Spanish settlement of Trinidad. Raleigh would, however, exaggerate the wealth found there upon his return to England. Supporting Raleigh with his expedition was another led by Amyas Preston and George Somers known as the Preston Somers expedition to South America, notable for a daring overland assault that saw the capture of Caracas.

Many of the expeditions were financed by famed London merchants, the most notable of these being John Watts. An expedition Watts financed to Portuguese Brazil led by James Lancaster saw the capture and plunder of Recife and Olinda – which was highly profitable for both.[41] In response to English privateering against their merchantmen, the Spanish monarchy struck back with the Dunkirkers devastating English shipping and fishing in the largely undefended seas around England.

By far the most successful English privateer was Christopher Newport, who was backed financially by Watts.[42] Newport set out in 1590 to raid the Spanish West Indies and in the ensuing fight saw the defeat of an armed Spanish convoy but Newport lost his right arm in the process. Despite this Newport continued the ventures – the blockade of Western Cuba in 1591 was the most successful English privateering venture made during the war.[43] Both Drake and Hawkins died of disease on the later 1595–96 expedition against Puerto Rico, Panama, and other targets in the Spanish Main, a severe setback in which the English suffered heavy losses in soldiers and ships despite a number of minor military victories.

In August 1595, a Spanish naval force from Brittany led by Carlos de Amésquita landed in Cornwall, raiding and burning Penzance and several nearby villages.

During the summer of 1596, an Anglo-Dutch expedition under Elizabeth's young favourite, the Earl of Essex, sacked Cádiz, causing significant loss to the Spanish fleet, leaving the city in ruins and delaying a projected descent on England. The allies were unable to capture the treasure, as the Spanish commander had time in order to torch the treasure ships in port, sending the treasure to the bottom of the harbour, from where it was later recovered. Despite its failure to capture the treasure fleet, the sack of Cádiz was celebrated as a national triumph comparable to the victory over the Spanish Armada, and for a time Essex's prestige rivalled Elizabeth's own.[44]

Instead of controlling and taxing its subjects, the English crown competed with them for private profit; it failed to succeed at this, as the great naval expeditions were on the whole unprofitable.[45] The last of the great English naval expeditions took place in 1597, led by the Earl of Essex, known as the Islands Voyage. The objective was to destroy the Spanish fleet and intercept a treasure fleet in the Azores. Neither was achieved and the expedition ended in costly failure, and Essex on his return was scolded by the Queen for not protecting the English coast.

While the war became a great drain on the English treasury, it proved to be profitable for a number of English privateers. In its final years, English privateering continued despite the strengthening of Spanish navy convoys – Cumberland's last expedition in 1598 to the Caribbean led to the capture of San Juan, and had succeeded where Drake had failed. Newport struck at Tobasco in 1599 while William Parker successfully raided Portobello in 1601.[46] In 1603 Christopher Cleeve struck at Santiago de Cuba and in the last raid of the war Newport plundered Puerto Caballos.[47] Finally, just days before the signing of the peace treaty in August 1604, future admiral Antonio de Oquendo defeated and captured an English privateer in the Gulf of Cádiz.[48]

By the end of the war, English privateering had devastated the Spanish private merchant marine.[49] The most famous pirates lauded by English literature and propaganda tended to attack fishing vessels or boats of small value to the Spanish crown.[50] Spanish prizes though were taken at an attritional rate; nearly 1,000 were captured by the war's end, and there was on average a declared value of approximately £100,000–£200,000 for every year of the war.[51] In addition, for every Spanish prize brought back, another was either burned or scuttled, and the presence of so many English corsairs deterred some Spanish merchantmen from putting to sea.[52] This resulted in much Spanish and Portuguese commerce being carried on Dutch and English ships, which in itself created competition.[38] Nevertheless, throughout the war Spain's important treasure fleets were kept safe by their convoy system.[1]

Dutch Revolt (1598–1604)

In 1598, the Spanish under Francisco Mendoza retook Rheinberg and Meurs in a campaign known as the Spanish winter of 1598–99. Mendoza then attempted to take Bommelerwaard island but the Dutch and English under Maurice thwarted the attempt and defeated him at Zaltbommel. Mendoza retreated from the area and the defeat resulted in chaos in the Spanish army – mutinies took place and many deserted. The following year the Dutch senate led by Johan van Oldenbarneveldt saw the chaos in the Spanish army and decided the time was ripe for a focal point of the war to be concentrated in Catholic Flanders. Despite a bitter dispute between Maurice and van Oldenbarneveldt, the Dutch and a sizeable contingent of the English Army under Francis Vere reluctantly agreed. They used Ostend (still in Dutch hands) as a base to invade Flanders. Their aim was to conquer the privateer stronghold city of Dunkirk. In 1600 they advanced toward Dunkirk and in a pitched battle the Anglo-Dutch inflicted a rare defeat on the tercio-led Spanish army at the Battle of Nieuwpoort in which the English played a major part.[53] Dunkirk was never attempted however as disputes in the Dutch command meant that taking Spanish-occupied cities in the rest of the Republic took priority. Maurice's force thus withdrew leaving Vere to command Ostend in the face of an imminent Spanish siege.[54]

With the siege of Ostend underway, Maurice then went on the offensive on the Rhine frontier in the summer of 1600. Rheinberg and Meurs were thus retaken from the Spanish yet again, although an attempt on s'Hertogenbosch failed during the winter months. At Ostend in January 1602 after being reinforced, Vere faced a huge Spanish frontal assault organised by the Archduke Albert and in bitter fighting this was repelled with heavy losses. Vere left the city soon after and joined Maurice in the field, while Albert, who drew much criticism from army commanders for his tactics, was replaced by the talented Ambrogio Spinola. The siege dragged on for another two years as the Spanish attempted to take Ostend's strongpoints in a costly war of attrition. Around the same time Maurice continued his campaign, Grave was retaken but Vere was severely wounded during the siege. An attempt by the Dutch and English to relieve Ostend took place in mid-1604 but the inland of port of Sluis was besieged and captured instead. Soon afterwards the Ostend garrison finally surrendered, after a siege of nearly four years and costing thousands of lives; for the Spanish, it was a pyrrhic victory.[55][56]

France

Normandy added a new front in the war and the threat of another invasion attempt across the channel. In 1590, the Spanish landed a considerable force in Brittany to assist the French Catholic League, expelling the English and Huguenot forces from much of the area. Henry IV's conversion to Catholicism in 1593 won him widespread French support for his claim to the throne, particularly in Paris (where he was crowned the following year), a city that he had unsuccessfully besieged in 1590. In 1594 Anglo-French forces were able to end Spanish hopes of using the large port of Brest as a launching point for an invasion of England by capturing Fort Crozon.

The French Wars of Religion turned increasingly against the hardliners of the French Catholic League. With the signing of the Triple Alliance in 1596 between France, England, and the Dutch, Elizabeth sent a further 2,000 troops to France after the Spanish took Calais. In September 1597 Anglo-French forces under Henry retook Amiens, just six months after the Spanish took the city, bringing to a halt a string of Spanish victories. In fact, the first tentative talks on peace between the French and Spanish crowns had already begun before the battle and the League hardliners were already losing popular support throughout France to a resurgent Henry after his conversion to Roman Catholicism which was bolstered by his military successes. In addition, Spanish finances were at breaking point because of fighting wars in France, the Netherlands, and against England. Therefore, a deeply ill Philip decided to end his support for the League and to finally recognize the legitimacy of Henry's accession to the French throne. Without Spanish support, the last League hardliners were quickly defeated. In May 1598, the two kings signed the Peace of Vervins ending the last of the religious civil wars and the Spanish intervention with it.[57]

Ireland

In 1594, the Nine Years' War in Ireland had begun, when Ulster lords Hugh O'Neill and Red Hugh O'Donnell rose up against English rule with fitful Spanish support, mirroring the English support of the Dutch rebellion. While English forces were containing the rebels in Ireland at great cost in men, general suffering, and finance, the Spanish attempted two further armadas, in 1596 and 1597: the first was shattered in a storm off northern Spain, and the second was frustrated by adverse weather as it approached the English coast. Philip II died in 1598, and his successor Philip III continued the war but with less enthusiasm.

At the end of 1601, the Spanish sent a final armada north, this time a limited expedition intended to land troops in Ireland to assist the rebels. Only half the fleet arrived because of a storm that scattered it and that which did arrive landed far from Irish rebel forces. The Spanish entered the town of Kinsale with 3,000 troops and were immediately besieged by the English. In time, their Irish allies arrived to surround the besieging force but the lack of communication with the rebels led to an English victory at the Battle of Kinsale. The besieged Spanish accepted the proposed terms of surrender and returned home, while the Irish rebels hung on, surrendering in 1603, just after Elizabeth died.

End of the war and treaty

With the end of the war in France, Philip III sought peace with England as well. By 1598 the war had become long and costly for Spain. England and Dutch Republic too were war-weary and both sides felt the need for peace.[58] However, in peace negotiations at Boulogne in 1600, Spanish demands were adamantly rejected by the English and Dutch. Nevertheless, diplomatic routes remained open between the Archduke of Austria and his wife Infanta Isabella (Philip's sister) who differed in their policies to Philip's. Philip wanted to preserve the hegemony of the Spanish empire, whilst the Archduke and Isabella sought peace and friendly relations.[59]

Soon after victory in Ireland the following year, the English navy under Richard Leveson conducted a blockade of Spain, the first of its kind.[citation needed] Off Portugal, they sailed into Sesimbra bay where a fleet of eight Spanish galleys under Federico Spinola (brother of Ambrogio) and Álvaro de Bazán were present.[60] Spinola had already established his base at Sluis in Flanders and was gathering more with an intent on a potential strike against England. In June 1602 Leveson defeated the Spanish which resulted in two galleys sunk and the capture of a rich Portuguese carrack.[61] Months later in the English channel Spinola's fleet gathered more galleys and sailed through the English channel once more but was defeated again by an Anglo-Dutch naval squadron off the Dover straits. Spinola's remaining galleys eventually reached Sluis.[62] The result of this action forced the Spanish to cease further naval operations against England for the remainder of the war.[61] Spain's priority was no longer an invasion of England, but the fall of Ostend.[62]

After the death of Elizabeth in 1603, James I, became the new king of England. He was the Protestant son and successor to the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, whose execution had been a proximate cause of the war. James regarded himself as the peacemaker of Europe, and the ultimate aim of his idealistic foreign policy was the reunion of Christendom.[63] James sought an end to the long and draining conflict, which Philip III also wanted. James ordered an end to further privateering, and in return Philip sent a Spanish-Flemish Commission headed by Juan de Tassis to London to explore the possibilities of ending the war.

After nearly a year of negotiations, peace was signed between the nations on 28 August 1604, place at Somerset House in Westminster. The sieges of Ostend and Sluis were allowed to continue until the end of those respective campaigns.[64]

Aftermath

The treaty restored the status quo ante bellum; the terms were favourable both to Spain and England.[1][65] For Spain the treaty secured her position as a leading power in the world.[66][67] Spain's upgrading of the convoy system had allowed it to defend its treasure fleets and retain its New World colonies. English support for the Dutch rebellion against the Spanish king, the original cause of the war, ceased. The Spanish could then concentrate their efforts on the Dutch, in the hopes of bringing them to their knees.[65][68] A complete abandonment of the Dutch cause, however, was not promised in the treaty.[68] The English-held cautionary towns in Holland on the other hand were not surrendered despite Spanish demands.[69] The sieges of Ostend and Sluis were allowed to continue until the end of those respective campaigns.[70] The Dutch by 1607 had in fact prevailed; the Spanish did not deliver their knock out blow they had hoped for and the Twelve Years' Truce effectively recognized the independence of the Republic.[71][72]

For England the treaty was a diplomatic triumph as well as an economic necessity.[73] At the same time, the treaty was highly unpopular with the English public, many of whom considered it a humiliating peace.[74][75][76] Many felt that James had abandoned England's ally, the Netherlands, in order to appease the Spanish crown and this damaged James's popularity.[73] The treaty, however, made sure the Protestant reformation there had been protected, and James and his ministers refused the Spanish demand for Catholic toleration in England.[68] After the defeat at Kinsale in 1602, the Treaty of Mellifont was concluded the following year between James I and the Irish rebels. In the subsequent London treaty Spain pledged not to support the rebels.[69]

The treaty was well received in Spain.[77][78] Large public celebrations were held at Valladolid, the Spanish capital,[79][80] where the treaty was ratified in June 1605, in the presence of a large English ambassadorial delegation led by Lord Admiral Charles Howard.[77] Nevertheless, some members of the Catholic clergy criticized Philip III's willingness to sign a treaty with a "heretical power".[81]

The provisions of the treaty authorised merchants and warships of both nations to operate from each other's respective ports. English trade with the Spanish Netherlands (notably the city of Antwerp) and the Iberian peninsula was resumed.[68] Spanish warships and privateers were able to use English ports as naval bases to attack Dutch shipping[82] or to ferry troops to Flanders.[83]

The war had diverted Tudor colonial efforts,[84] but the English who had invested in privateering expeditions during the war garnered enormous windfall profits, leaving them well placed to finance new ventures.[51] As a result, the London Company was able to establish a settlement in Virginia in 1607.[85] The establishment of the East India Company in 1600 was significant for the growth of England (and later Great Britain) as a colonial power.[86] A factory was established at Banten, Java, in 1603 while the Company had successfully and profitably breached the Spanish and Portuguese monopoly.[87][88] While the incipient illegal trade with the Spanish colonies was brought to an end, there was deadlock over English demands for the right to trade in the East and West Indies, which Spain adamantly opposed. Eventually the complications resulted in the treaty avoiding any mention of the matter.[68]

For Spain there was hope that England would eventually secure tolerance for Catholics but the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 destroyed any possibility of this.[89] The resulting anti-Catholic backlash following the discovery of the plot put to rest Protestant fears that a peace with Spain would ultimately mean an invasion by Jesuits and Catholic sympathisers, as the Elizabethan recusancy laws were rigidly enforced by Parliament.[90]

England and Spain remained at peace until 1625.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c Hiram Morgan (September–October 2006). Teaching the Armada: An Introduction to the Anglo-Spanish War, 1585–1604. Vol. 14. History Ireland. p. 43.

- ^ Penry Williams (1998). The Later Tudors: England 1547-1603. Oxford University Press. p. 382.

- ^ a b Micheal Clodfelter (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015. p. 21.

- ^ Rowse, A. L (1955). The Expansion of Elizabethan England. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 241. ISBN 978-1403908131.

- ^ Graham 1972, pp. 258–61.

- ^ Davenport, Frances Gardiner; & Paullin, Charles Oscar. European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States and Its Dependencies, The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2004 ISBN 1-58477-422-3, ISBN 978-1-58477-422-8

- ^ O'Connor, Thomas (2016). Irish Voices from the Spanish Inquisition Migrants, Converts and Brokers in Early Modern Iberia. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 9781137465900.

- ^ Tracey pp. 157–158

- ^ Bicheno p. 180

- ^ Karen Ordahl Kupperman, The Jamestown Project

- ^ Konstam pp. 76–77

- ^ Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1887). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 9. Macmillan. pp. 358–363. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Hammer 2003 pp. 125–127

- ^ Wilson 1981 pp. 282–284

- ^ t' Hart pp. 21–22

- ^ Wilson 1981 pp. 291–294

- ^ Wilson 1981 pp. 294–295

- ^ Pollen, John Hungerford (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company. "Pope Sixtus V agreed to renew the excommunication of the Queen, and to grant a large subsidy to the Armada, but, knowing the slowness of Spain, would give nothing till the expedition should actually land in England. In this way, he was saved his million crowns, and spared the reproach of having taken futile proceedings against the heretic queen."

- ^ Hanson p. 379

- ^ Parker & Martin p. 215

- ^ Richard Holmes 2001, p. 858: "The 1588 campaign was a major English propaganda victory, but in strategic terms, it was essentially indecisive."

- ^ "Events at Calais, the 'fireships' and the Battle of Gravelines – the Spanish Armada". BBC Bitesize.

- ^ Wernham, R. B. (1988). The Expedition of Sir John Norris and Sir Francis Drake to Spain and Portugal, 1589. Aldershot: Temple Smith for the Navy Records Society. p. 240. ISBN 0566055783.

- ^ Gonzalez-Arnao Conde-Luque, Mariano (1995). Derrota y muerte de Sir Francis Drake, a Coruña 1589 – Portobelo 1596 (in Spanish). Xunta de Galicia, Servicio Central de Publicacións. p. 94. ISBN 978-8445314630.

- ^ R. B. Wernham, "Queen Elizabeth and the Portugal Expedition of 1589: Part II", English Historical Review 66/259 (April 1951), pp. 204–214

- ^ a b Gorrochategui Santos, Luis (2018). English Armada: The Greatest Naval Disaster in English History. New York: Bloomsbury. pp. 245–246. ISBN 978-1350016996.

- ^ R. O. Bucholz, Newton Key. Early modern England 1485–1714: a narrative history (John Wiley and Sons, 2009). ISBN 978-1405162753 p. 145

- ^ John Hampden Francis Drake, privateer: contemporary narratives and documents (Taylor & Francis, 1972). ISBN 978-0817357030 p. 254

- ^ Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1972). Armada Española desde la unión de los Reinos de Castilla y Aragón (PDF) (in Spanish). Vol. III. Museo Naval de Madrid, Instituto de Historia y Cultura Naval. p. 51.

- ^ J. H. Elliott. La Europa dividida (1559–1598) (in Spanish) (Editorial Critica, 2002). ISBN 978-8484326694 p. 333

- ^ a b Davies, Charles Maurice (1851). The History of Holland and the Dutch nation: from the beginning of the tenth century to the end of the eighteenth. G. Willis. pp. 225–28.

- ^ a b Knight, Charles Raleigh (1905). Historical records of The Buffs, East Kent Regiment (3rd Foot) formerly designated the Holland Regiment and Prince George of Denmark's Regiment. Vol I. London, Gale & Polden, pp. 36–40

- ^ Hadfield & Hammond p. 49

- ^ Motley, John Lothrop. History of the United Netherlands: from the Death of William the Silent to the Twelve Years' Truce – 1609. Vol. 3. p. 422.

- ^ Casaban Banaclocha, Jose L. (2017). The Twelve Apostles: Design, Construction, and Function of Late 16th-Century Spanish Galleons (Thesis). Texas A & M University. p. 45. hdl:1969.1/173235.

- ^ Monson, William (1902). The naval tracts of Sir William Monson (PDF). Vol. IV, bk. III. London: Printed for the Navy Records Society. pp. 73–74.

- ^ Andrews pp. 124–125

- ^ a b Bicheno p. 320

- ^ Andrews p. 73

- ^ McCulloch, John Ramsay (1833). A Treatise on the Principles, Practice, & History of Commerce. Baldwin and Cradock. p. 120.

- ^ Andrews p. 77

- ^ Bicheno pp. 316–318

- ^ Andrews p. 167

- ^ David Starkey, Elizabeth (Channel 4, 1999), Episode 4, "Gloriana".

- ^ Andrews p. 30

- ^ Andrews pp. 177

- ^ Bradley p. 131

- ^ Estrada y Arnáiz, Rafael (1943). El almirante don Antonio de Oquendo (in Spanish). Espasa-Calpe. p. 32.

- ^ Andrews p. 226

- ^ Chamorro, Germán Vázquez (2004). Mujeres piratas. Madrid: Algaba. ISBN 978-8496107267.

- ^ a b Hornsby & Hermann p. 17

- ^ Bradley pp. 109–110

- ^ Borman pp. 224–225

- ^ Knight p. 49

- ^ Edmundson pp. 102–103

- ^ Watson & Thomson, Robert & William (1792). The History of the Reign of Philip III. King of Spain Authors. p. 154.

- ^ Ireland, William Henry (1824). Memoirs of Henry the Great, and of the Court of France During His Reign. Vol. 2. Harding, Triphook & Lepard. p. 266.

- ^ MacCaffrey pp. 226–230

- ^ McCoog pp. 222–223

- ^ Duerloo pp. 137–138

- ^ a b Wernham pp. 400–401

- ^ a b Beri, Emiliano (2018). Spinola, Federico (in Italian). Vol. 93. Treccani. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ W. B. Patterson, King James VI and I and the Reunion of Christendom (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- ^ Rowse 1973, p. 413.

- ^ a b Allen pp. 142–143

- ^ Douglas R. BurgessThe Pirates' Pact: The Secret Alliances Between History's Most Notorious Buccaneers and Colonial America. McGraw-Hill Professional, 2008, p. 29. ISBN 0-07-147476-5

- ^ Channing, Edward: A history of the United States. Octagon Books, 1977, v. 1, p. 158. ISBN 0-374-91414-1

- ^ a b c d e Hammer, Paul E. J (2003). Elizabeth's Wars: War, Government and Society in Tudor England, 1544–1604. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-1137173386.

- ^ a b Fritze, Ronald H; Robison, William B (1996). Historical Dictionary of Stuart England, 1603–1689. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 310. ISBN 978-0313283918.

- ^ Rowse, A. L (1973). The Expansion of Elizabethan England. Cardinal Books. p. 413. ISBN 978-0351180644.

- ^ Israel (1995), pp. 399–405

- ^ Phelan, John Leddy (1967). The Kingdom of Quito in the Seventeenth Century: Bureaucratic Politics in the Spanish Empire. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 88.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Smout, T. C. (2005). Anglo-Scottish Relations from 1603 to 1900. OUP/British Academy. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0197263303.

- ^ Smout, T. C. (2005). Anglo-Scottish Relations from 1603 to 1900. OUP/British Academy. p. 17. ISBN 978-0197263303.

- ^ Lothrop Motley, John (1867). History of the United Netherlands: From the Death of William the Silent to the Twelve Year's Truce – 1609, Vol. 4. p. 223.

- ^ Moseley, C. W. R. D. (2007). English Renaissance Drama: A Very Brief Introduction to Theatre and Theatres in Shakespeare's Time. Humanities. p. 90. ISBN 978-1847601834.

- ^ a b Pericot Garcia, Luis (1970). La Casa de Austria (siglos XVI y XVII) por La Ullon Cisneros y E. Camps Cazeria (in Spanish). Instituto Gallach de Librería y Ediciones. p. 179.

- ^ Feros, Antonio (2002). El Duque de Lerma: realeza y privanza en la España de Felipe III (in Spanish). Marcial Pons Historia. p. 305. ISBN 978-8495379399.

- ^ Otero Novas, José Manuel (2001). Fundamentalismos enmascarados (in Spanish). Editorial Ariel. p. 153. ISBN 978-8434412248.

- ^ Herrero García, Miguel (1966). Biblioteca románica hispánica: Estudios y ensayos (in Spanish). Gredos. p. 474.

- ^ Ortiz, Antonio Domínguez (1971). The Golden Age of Spain, 1516–1659 Volume 1 of The History of Spain. Basic Books. p. 87. ISBN 978-0046526900.

- ^ Sanz Camañes, Porfirio (2002). Diplomacia hispano-inglesa en el siglo XVII: razón de estado y relaciones de poder durante la Guerra de los Treinta Años, 1618–1648 (in Spanish). Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. p. 108. ISBN 978-8484271550.

- ^ Rodríguez Hernández, Antonio José (2015). Breve historia de los Tercios de Flandes (in Spanish). Ediciones Nowtilus. p. 144. ISBN 978-8499676586.

- ^ Billings p. 3

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica. Vol. I. Encyclopedia Britannica Company. 1973. p. 499.

- ^ Hart, Jonathan (2008). Empires and Colonies Empires and Colonies. Polity. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0745626130.

- ^ Chaudhuri, K. N (1965). The English East India Company: The Study of an Early Joint-stock Company 1600–1640. Taylor & Francis. p. 3. ISBN 978-0415190763.

- ^ Wernham pp. 333–334

- ^ Allen p. 155

- ^ Reed, Richard Burton (1970). Sir Robert Cecil and the Diplomacy of the Anglo-Spanish Peace, 1603–1604. University of Wisconsin-Madison. pp. 228–229.

Further reading

- Allen, Paul C (2000). Philip III and the Pax Hispanica, 1598–1621: The Failure of Grand Strategy. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300076820.

- Andrews, Kenneth R (1964). Elizabethan Privateering: English Privateering During the Spanish War, 1585–1603. Cambridge University Press, First Edition. ISBN 978-0521040327.

- Bradley, Peter T (2010). British Maritime Enterprise in the New World: From the Late Fifteenth to the Mid-eighteenth Century. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0773478664.

- Bormen, Tracey (1997). Sir Francis Vere in the Netherlands, 1589–1603: A Re-evaluation of His Career as Sergeant Major General of Elizabeth I's Troops. University of Hull.

- Charles Beem, The Foreign Relations of Elizabeth I (2011) excerpt and text search

- Bicheno, Hugh (2012). Elizabeth's Sea Dogs: How England's Mariners Became the Scourge of the Seas. Conway. ISBN 978-1844861743.

- Billings, Warren M, ed. (1975). The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia, 1606–1689. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0807812372.

- Duerloo, Luc (2012). Dynasty and Piety: Archduke Albert (1598–1621) and Habsburg Political Culture in an Age of Religious Wars. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1409443759.

- Peter Earle The Last Fight of the Revenge (London, 2004) ISBN 0-413-77484-8

- Edmundson, George (2013). History of Holland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107660892.

- * Graham, Winston (1972). The Spanish Armadas. Collins. ISBN 978-0002218429.

- Gorrochategui Santos, Luis (2018). English Armada: The Greatest Naval Disaster in English History. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1350016996.

- Hadfield, Andrew; Hammond, Paul, eds. (2014). Shakespeare And Renaissance Europe Arden Critical Companions. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1408143681.

- Hammer, Paul E. J (2003). Elizabeth's Wars: War, Government and Society in Tudor England, 1544–1604. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137173386.

- Hanson, Neil (2011). The Confident Hope Of A Miracle: The True History Of The Spanish Armada. Random House. ISBN 978-1446423226.

- Hornsby, Stephen; Hermann, Michael (2005). British Atlantic, American Frontier: Spaces of Power in Early Modern British America. UPNE. ISBN 978-1584654278.

- Jonathan I. Israel. Conflicts of Empires: Spain, the Low Countries, and the Struggle for World Supremacy, 1585–1713 (1997) 420pp

- Israel, Jonathan (1995). The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-873072-9.

- Konstam, Angus (2000). Elizabethan Sea Dogs 1560–1605 (Elite). Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-015-5.

- MacCaffrey, Wallace T (1994). Elizabeth I: War and Politics, 1588–1603. Princeton Paperbacks Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691036519.

- McCoog, Thomas M (2012). The Society of Jesus in Ireland, Scotland, and England, 1589–1597: Building the Faith of Saint Peter Upon the King of Spain's Monarchy. Ashgate & Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu. ISBN 978-1-4094-3772-7.

- Parker, Geoffrey; Martin, Colin (1999). The Spanish Armada: Revised Edition. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1901341140.

- 't Hart, Marjolein (2014). The Dutch Wars of Independence: Warfare and Commerce in the Netherlands 1570–1680. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-73422-6.

- Tracy, James D. (2006). Europe's Reformations, 1450–1650: Doctrine, Politics, and Community Critical Issues in World and International History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0742579132.

- Wernham, R.B. (1994). The Return of the Armadas: The Last Years of the Elizabethan Wars Against Spain 1595–1603. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820443-5.

- Wilson, Derek (1981). Sweet Robin: A Biography of Robert Dudley Earl of Leicester 1533–1588. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-10149-0.

![The Battle of Gravelines, 8 August 1558,[22][better source needed] by Nicholas Hilliard](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/La_batalla_de_Gravelinas%2C_por_Nicholas_Hilliard.jpg/500px-La_batalla_de_Gravelinas%2C_por_Nicholas_Hilliard.jpg)