Sea monster

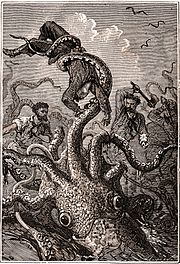

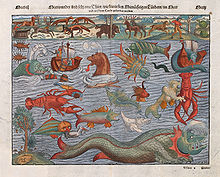

Sea monsters are beings from folklore believed to dwell in the sea and are often imagined to be of immense size. Marine monsters can take many forms, including sea dragons, sea serpents, or tentacled beasts. They can be slimy and scaly and are often pictured threatening ships or spouting jets of water. The definition of a "monster" is subjective; further, some sea monsters may have been based on scientifically accepted creatures, such as whales and types of giant and colossal squid.

Sightings and legends

Sea monster accounts are found in virtually all cultures that have contact with the sea. For example, Avienius relates of Carthaginian explorer Himilco's voyage "...there monsters of the deep, and beasts swim amid the slow and sluggishly crawling ships." (lines 117–29 of Ora Maritima). Sir Humphrey Gilbert claimed to have encountered a lion-like monster with "glaring eyes" on his return voyage after formally claiming St. John's, Newfoundland (1583) for England.[1] Another account of an encounter with a sea monster comes from July 1734. Hans Egede, a Dano-Norwegian missionary, reported that on a voyage to Godthåb on the western coast of Greenland he observed:[2]

a most terrible creature, resembling nothing they saw before. The monster lifted its head so high that it seemed to be higher than the crow's nest on the mainmast. The head was small and the body short and wrinkled. The unknown creature was using giant fins which propelled it through the water. Later the sailors saw its tail as well. The monster was longer than our whole ship.

Ellis (1999) suggested the Egede monster might have been a giant squid.

There is a Tlingit legend about a sea monster named Gunakadeit (Goo-na'-ka-date) who brought prosperity and good luck to a village in crisis, people starving in the home they made for themselves on the southeastern coast of Alaska.

Other reports are known from the Pacific, Indian and Southern Oceans (e.g. see Heuvelmans 1968). Cryptozoologists suggest that modern-day sea monsters are surviving specimens of giant marine reptiles, such as an ichthyosaur or plesiosaur, from the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods, or extinct whales like Basilosaurus. Ship damage from Tropical cyclones such as hurricanes or typhoons may also be another possible origin of sea monsters.

In 1892, Anthonie Cornelis Oudemans, then director of the Royal Zoological Gardens at The Hague, saw the publication of his The Great Sea Serpent, which suggested that many sea serpent reports were best accounted for as a previously unknown giant, long-necked pinniped.

It is likely that many other reports of sea monsters are misinterpreted sightings of shark and whale carcasses (see below), floating kelp, logs or other flotsam such as abandoned rafts, canoes and fishing nets.

Alleged carcasses

Sea monster corpses have been reported since recent antiquity (Heuvelmans 1968). Unidentified carcasses are often called globsters. The alleged plesiosaur netted by the Japanese trawler Zuiyō Maru off New Zealand caused a sensation in 1977 and was immortalized on a Brazilian postage stamp before it was suggested by the FBI to be the decomposing carcass of a basking shark. Likewise, DNA testing confirmed that an alleged sea monster washed up on Newfoundland in August 2001, was a sperm whale.[3]

Another modern example of a "sea monster" was the strange creature washed up in Los Muermos on the Chilean sea shore in July 2003. It was first described as a "mammoth jellyfish as long as a bus" but was later determined to be another corpse of a sperm whale. Cases of boneless, amorphic globsters are sometimes believed to be gigantic octopuses, but it has now been determined that sperm whales dying at sea decompose in such a way that the blubber detaches from the body, forming featureless whitish masses that sometimes exhibit a hairy texture due to exposed strands of collagen fibers. The analysis of the Zuiyō Maru carcass revealed a comparable phenomenon in decomposing basking shark carcasses, which lose most of the lower head area and the dorsal and caudal fins first, making them resemble a plesiosaur.

In May 2017, The Guardian published an article claiming a giant sea monster's corpse was found in Indonesia, and also published an alleged photograph of "it."[4]

Example

- Aspidochelone, a giant turtle or whale that appeared to be an island and lured sailors to their doom

- Bakunawa

- Bloop (sound) Because it was spreading worldwide

- Capricorn, Babylonian sea goat featured in the Zodiac

- Cai Cai-Vilu

- Cetus, a monster sent by Poseidon to devour Andromeda, only to be destroyed by Perseus

- Charybdis of Homer, a monster whose mouth formed a whirlpool that sucked any ship nearby beneath the ocean

- Cirein-cròin

- Curruid, from whose bone the Gae Bulg is made in Celtic mythology

- Devil Whale, a demonic whale the size of an island

- Hafgufa, a whale of fabulous size, described as a sjóskrímsli 'sea monster' together with the lyngbakr

- Hydra, Greek multi-headed dragon-like beast

- Iku-Turso, reputedly a type of colossal octopus or walrus

- Ipupiara

- Jörmungandr, the Midgard Serpent and nemesis of Thor in Norse mythology

- Kraken, a gigantic octopus, squid, or crab-like creature

- Lacovie

- Leviathan

- Lusca

- Makara

- Proteus

- Scylla of Homer, a six-headed, twelve-legged serpentine monster that devoured six men from each ship that passed by

- Sirens

- Taniwha

- Tiamat

- Timingila

- Umibōzu

- Yacumama

Older reports

Sea monsters reported first or second hand include:

- A giant octopus by Pliny (not to be confused with the documented Giant Pacific octopus)

- Sea monk

- Various sea serpents

- Tritons by Pliny[citation needed]

- Cormac Ua Liatháin in the 6th century supposedly saw a horde of tiny creatures the size of frogs that had spines, which attacked his boat in the North Atlantic according to an account written by Adomnan of Iona[5]

Newer reports

- Cadborosaurus of the Pacific Northwest

- Champ of Lake Champlain

- Chessie of the Chesapeake Bay

- Nessie of Loch Ness

- Issie of Lake Ikeda, Kyushu

- Ogopogo of Okanagan Lake

- Lusca

- Morgawr

- Ningen, a humanoid creature sighted in the seas north of Japan[6]

- Fjörulalli, also called Shore Laddie, Arnarfjörður, Westfjords, Iceland[7]

- Sea Horse Arnarfjörður, Westfjords, Iceland[7]

- The Shell monster Arnarfjörður, Westfjords, Iceland[7]

- Hafmaður Arnarfjörður, Westfjords, Iceland[7]

In fiction

- Great Fish in the Hebrew Bible's Book of Jonah

- Creatures of H. P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos, including Cthulhu itself.

- Creatures in such sci-fi/horror films as Deepstar Six, The Rift, Deep Rising and Deep Shock.

- Clover

- Cyrus from Cyrus the Unsinkable Sea Serpent by Bill Peet

- Fictional portrayals of the Giant Squid, like in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas.

- Giant octopus in It Came from Beneath the Sea.

- Iku-Turso in Lönnrot's Kalevala

- Giganto

- Godzilla

- Mothra (Aqua Form)

- Gorgo

- Manda

- Kraken as depicted in Clash of the Titans (both the 1981 and 2010 versions).

- Kraken as depicted in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest.

- Ebirah

- Titanosaurus

- Zigra

- Moby Dick

- Rhedosaurus

- The Terrible Dogfish

- Jaws

- Sigmund and the Sea Monsters

- Sea Serpent as depicted in C.S. Lewis' novel, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, and its 2010 film adaptation, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

- The Meg, the giant moray eel Great Abaia, and the giant squid Lusca. The Great are 3 sea monsters featured as bosses in the survival video game "Stranded Deep"

- The sea monster from Monkeybone is an inhabitant of Down Town and is performed by Nathan Stein. It resembles a piscine humanoid that is protruding from the back of its large seahorse-like mount.

- In Ninjago: Seabound, Wojira is a Giant Sea Serpent/Dragon that can control water and wind using the storm and wave amulets.

- In the 1980 film Doraemon: Nobita's Dinosaur, Piisuke is Nobita's pet dinosaur and sea monster.

- In the 2021 film Luca, Luca Paguro and his friend Alberto Scorfano are 12–13 year old humanoid sea monsters that assume the form of Humans when they are dry on land.

- The 2022 film The Sea Beast featured an assortment of sea monsters.

See also

- Basilosaurus

- Colossal squid

- Giant squid

- Ichthyosauria

- Megalodon

- Mosasaur

- Plesiosaur

- Pliosaur

- Here be dragons

References

- ^ Edward Haies: Sir Humphrey Gilbert's Voyage To Newfoundland, 1583 In the fifth section after the notice "Footnote 11: Stephen Parmenius"

- ^ J. Mareš, Svět tajemných zvířat, Prague, 1997

- ^ Carr, S.M., H.D. Marshall, K.A. Johnstone, L.M. Pynn & G.B. Stenson 2002. How To Tell a Sea Monster: Molecular Discrimination of Large Marine Animals of the North Atlantic. Biological Bulletin 202: 1-5.

- ^ "Do sea monsters exist? Yes, but they go by another name … | Jules Howard". the Guardian. 2017-05-18. Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ Adomnan of Iona. Life of St Columba. Penguin books, 1995

- ^ "ช่วง เด็กพิลึก ตอน นินเจน สัตว์ประหลาดลึกลับใต้ท้องทะเล". BEC-TERO (in Thai). 2015-11-25. Archived from the original on 2019-02-02. Retrieved 2017-06-25.

- ^ a b c d "Monsters". Skrímslasetrið Bíldudal. 2013-04-09. Retrieved 2018-02-04.