Malcolm Sargent

Malcolm Sargent |

|---|

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (April 29 1895 – October 3 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer. He was widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works.

The well-known ensembles with which he was associated included the Ballets Russes, the Royal Choral Society, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company and the London Philharmonic, Hallé, Liverpool Philharmonic, BBC Symphony and Royal Philharmonic orchestras.

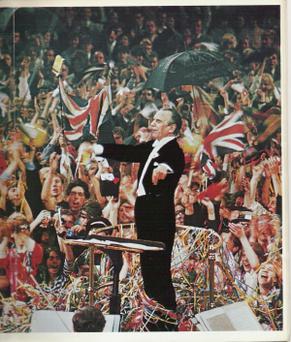

Sargent toured widely throughout the world and was noted for his debonair appearance, his skill as a choral conductor and his championship of British composers. From 1948 to 1967, as chief conductor of the Proms, London's most prestigious summer music festival, he was one of the best-known English conductors. To the British public, he was not only a popular musician but also a familiar broadcaster in BBC radio talk shows. To generations of Gilbert and Sullivan fans, he has been a major interpreter of their works through his recordings of the most popular Savoy Operas.

Life and career

Sargent was born in Bath Villas, Ashford in Kent, England, to a working-class family. His father was an amateur musician and part-time church organist. Sargent was brought up in Stamford, Lincolnshire, where he won a scholarship to Stamford School. At the age of fourteen he accompanied rehearsals for an amateur production of The Gondoliers and conducted a rehearsal of The Yeomen of the Guard at Stamford.[1] He earned his diploma as Associate of the Royal College of Organists at age sixteen. At eighteen, he was a Bachelor of Music.[2]

Early career

After a brief service in the army Sargent worked first as an organist at Melton Mowbray's St. Mary's Church, Leicestershire, beating more than 150 applicants for the post.[3] At the same time he worked on many musical projects in Leicester, Melton Mowbray and Stamford, where he not only conducted but also produced Gilbert and Sullivan and other operas for amateur societies.[4] The Prince of Wales and his entourage often hunted in Leicester and watched the annual Gilbert and Sullivan operas there, together with the Duke of York and other members of the Royal Family.[5] At the age of 24, Sargent became England's youngest Doctor of Music with a degree from Durham.[6]

Sargent's break came when Sir Henry Wood visited De Montfort Hall, Leicester, early in 1921 with the Queen's Hall orchestra. As it was customary to commission a piece from a local composer, he commissioned Sargent to write a piece, Impression on a Windy Day. Sargent completed the work too late for Wood to have enough time to learn it, and Wood called on Sargent to conduct the first performance himself.[7] Wood recognised not only the worth of the piece but also Sargent's talent as a conductor and gave him the chance to make his debut, conducting the work at The Proms in the Queen's Hall on 11 October of the same year.

Sargent soon abandoned composition in favour of conducting, on the advice of Wood among others. He founded the Leicester Symphony Orchestra, an amateur orchestra, in 1922 and it became good enough to obtain top-flight soloists, including Alfred Cortot, Artur Schnabel, Solomon, Guilhermina Suggia and Benno Moiseiwitsch, the last of whom gave Sargent lessons without charge, judging him talented enough to make a successful career as a concert pianist.[8] At the instigation of Wood and Adrian Boult, Sargent became a lecturer at the Royal College of Music, in London, in 1923.[9]

National fame

In the 1920s, Sargent became one of the best-known English conductors. For the British National Opera Company he conducted Die Meistersinger on tour in 1925[10], and for the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company he conducted London seasons at the Prince's Theatre in 1926 and the newly-rebuilt Savoy Theatre in 1929-30. Sargent was criticised for "tampering" with the Gilbert and Sullivan scores but demonstrated that, in fact, he had worked from Arthur Sullivan's manuscript scores and had removed alterations that had crept in over the years. Some of the principal cast members and the stage director, J. M. Gordon, also objected to Sargent’s fast tempi, at least at first.[11] The D’Oyly Carte seasons brought Sargent’s name to a wider public with an early BBC radio relay of The Mikado, in 1926, heard by up to eight million people. The Evening Standard noted that this was "probably the largest audience that has ever heard anything at one time in the history of the world."[12] In 1927 Sergei Diaghilev engaged Sargent to conduct for the Ballets Russes,[13] sharing the conducting with Igor Stravinsky and Sir Thomas Beecham.[14] Sargent also conducted for the final Ballets Russes season in 1928.[15] In 1928 he became conductor of the Royal Choral Society and he retained this post for four decades until his death. The society was famous in the 1920s and 1930s for staged performances of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor's Hiawatha at the Royal Albert Hall, with which work Sargent’s name rapidly became synonymous.[16][17]

Elizabeth Courtauld, wife of the industrialist Samuel Courtauld, promoted a popular series of subscription concerts beginning in 1929 and, on Schnabel’s advice, engaged Sargent as chief conductor with guest conductors as eminent as Bruno Walter, Otto Klemperer and Stravinsky.[18] The Courtauld-Sargent concerts, as they were known, were aimed at people who had not previously gone to concerts. They attracted large audiences, bringing Sargent’s name before another section of the public.[19] In addition to the core repertory, Sargent introduced new works by Arthur Bliss, Arthur Honneger, Zoltan Kodály, Bohuslav Martinů, Sergei Prokofiev, Karol Szymanowski and William Walton, among others.[20] At first, the plan was to engage the London Symphony Orchestra for these concerts, but the orchestra, a self-governing co-operative, refused to replace key players whom Sargent considered sub-standard.[21] As a result, Sargent, in conjunction with Beecham, set about establishing a new orchestra, the London Philharmonic.[22]

In these years Sargent tackled a wide range of repertoire, recording much of it, but he was particularly noted for performances of choral pieces. He consciously promoted British music, as he would throughout his career, conducting Handel's Messiah, performed with his large choruses; and the premières of At the Boar's Head (1925) by Gustav Holst; Hugh the Drover (1924) and Sir John in Love (1929) by Ralph Vaughan Williams; and Walton's oratorio Belshazzar's Feast (at the Leeds Triennial Festival of 1931). To popularise classical music, he conducted many concerts for young people, including the Robert Mayer Concerts for Children.[23]

Difficult years and war years

In October 1932, Sargent collapsed with tuberculosis. For almost two years he was unable to work and it was only later in the 1930s that he returned to the concert scene.[24] After giving an ill-advised Daily Telegraph interview in 1936, in which he said that an orchestra musician did not deserve a "job for life" and should "give of his lifeblood with every bar he plays", Sargent lost much favour with musicians. They were particularly annoyed because of their support of Sargent during his long illness. However, he continued to work, even though he faced hostility from British orchestras.

Being immensely popular in Australia (with players as well as public), Sargent made three lengthy tours of Australia and New Zealand in 1936, 1938 and 1939.[25] He was on the verge of accepting a permanent appointment with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation when, at the outbreak of World War II, he felt it his duty to return to his country, resisting strong pressure from the Australian media for him to stay.[26] He directed the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester (1939-1942) and the Liverpool Philharmonic (1942-1948) and became a popular BBC Radio Home Service broadcaster.[27] He helped boost public morale during the war by extensive concert tours around the country conducting for nominal fees.[28] On one famous occasion an air raid interrupted a performance of Beethoven's Symphony No. 7. Sargent stopped the orchestra, calmed the audience by saying they were safer inside the hall than fleeing outside, and resumed conducting.[29] He later said that no orchestra had ever played so well and that no audience, in his experience, had ever listened so intently.[30]

In 1945 Arturo Toscanini invited Sargent to conduct the NBC Symphony Orchestra. In four concerts, Sargent chose to present all English music, with the exception of Jean Sibelius's Symphony No. 1 and Antonin Dvořák's Symphony No. 7. Two concertos, Walton's Viola Concerto with William Primrose and Elgar's Violin Concerto with Yehudi Menuhin, were programmed as part of these concerts. Menuhin judged Sargent's conducting of the latter, "the next best to Elgar in this work."[31]

The Proms and later years

Sargent was knighted for his services to music in 1947 and performed in numerous English-speaking countries during the post-war years. He continued to promote British composers, conducting the premières of Walton's opera Troilus and Cressida (1954) and Vaughan Williams' Symphony No. 9 (1958).

For the BBC Sargent was chief conductor of the Proms from 1948 until his death in 1967 and of the BBC Symphony Orchestra from 1950 to 1957. He has been accused by one writer of "almost wreck[ing]" the BBC band during this time,[32] but in the 1950s and 1960s he made many recordings with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and others. In this period, Sargent returned to D'Oyly Carte Opera Company for the summer 1951 "Festival of Britain" season at the Savoy Theatre and the winter 1961-62 and 1963-64 seasons at the Savoy.

As chief conductor of the Proms, Sargent was noted for his witty addresses in which he good-naturedly chided the noisy prommers. In his programmes for these concerts, he often conducted choral music and music by British composers, but his range was broad: the BBC's official history of the Proms lists selected programmes from this period, showing Sargent conducting works by Bach, Sibelius, Dvorak, Berlioz, Rachmaninoff, Rimsky-Korsakov, Richard Strauss and Kodály in three successive programmes.[33] During his chief conductorship prestigious foreign conductors and orchestras began to perform regularly at the Proms. In his first season in charge Sargent and two other conductors conducted all the concerts between them; by 1966 there were Sargent and 25 other conductors. Those making their Prom debuts in the Sargent years included Carlo Maria Giulini, Georg Solti, Leopold Stokowski, Rudolf Kempe, Pierre Boulez and Bernard Haitink[34] The charity founded in Sargent's name continues to hold a special 'Promenade Concert' each year shortly after the main season ends.

Sargent made two tours of South America. In 1950, he conducted in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rio de Janiero and Santiago. His programmes included Vaughan Williams's London and 6th Symphonies; Haydn's Symphony No. 88, Beethoven's Symphony No. 8, Mozart's Jupiter, Schubert's 5th, Brahms's 2nd and 4th, Sibelius's 5th, Elgar's Serenade for Strings, Britten's Purcell Variations, Strauss's Till Eulenspiegel, Walton's Viola Concerto and Dvořák's Cello Concerto (with Pierre Fournier). The President of Uruguay addressed him thus: "We Uruguayans are fond of all English people, Sir Malcolm, but especially fond of you." In 1952 Sargent conducted in all the above-mentioned cities and also in Lima. Half his repertory on that tour consisted of British music and included Delius, Vaughan Williams, Britten, Walton and Handel’s Water Music.[35]

When the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra was in danger of extinction after Beecham’s death in 1961, Sargent played a major part in saving the orchestra, doing much to win back the good opinion of orchestral players that he had lost because of his 1936 interview.[36]

In the 1960s, Sargent toured in Russia, the United States, Canada, Turkey, Israel, India, the Far East and Australia.[37][38]By the mid-1960s, his health began to deteriorate. He underwent surgery in July 1967 for pancreatic cancer, made a valedictory appearance at the end of the last night of the Proms in September that year, and died in October at the age of 72.[39]

Personal life, reputation and legacy

Private life

In 1922, Sargent married Eileen Laura Harding Horne. Sargent’s biographers differ on her background. Aldous states that she was a maid in domestic service, whereas Reid notes that she was a keen rider, with many friends in hunting circles, and that her uncle (who officiated at her wedding to Sargent) was rector of Drinkwater, Suffolk.[40] According to Aldous, it was believed locally that Sargent had to marry Eileen having made her pregnant. By 1926, he and his wife had two children, a daughter, Pamela, who was to die of polio in 1944, and a son, Peter. But the marriage was unhappy and ended in divorce in 1946. Before, during and after his marriage, Sargent was a continual womaniser, a fact that he did not deny.[41] Among his affairs was a long-standing one with Edwina Mountbatten.[42] More casual encounters are typified by the young woman who said, "Promise me that whatever happens I shan’t have to go home alone in a taxi with Malcolm Sargent."[43]

Away from music, Sargent was elected a member of The Literary Society, a dining club founded in 1807 by Wordsworth and others.[44] He was also a member of the Beefsteak Club, for which his proposer was Sir Edward Elgar.[45]

Rupert Hart-Davis (who liked Sargent) called him a bounder;[46] Ethel Smyth (who did not) called him a "cad".[47] Despite that, and his philandering and ambition, Sargent was a deeply religious man all his life and was comforted on his deathbed by visits from the Anglican Archbishop of York, Donald Coggan, and the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal John Heenan.[48]

"Flash Harry"

A number of purported explanations have been advanced for Sargent's nickname "Flash Harry". Reid (p. 394) opines that it "was first in circulation among orchestral players before the war and that they used it in no spirit of adulation." It may have arisen from his impeccable appearance (he always wore a red or white carnation in his buttonhole, and the carnation is now the symbol of the school named for him). This was perhaps reinforced by his brisk tempi early in his career and by a story about his racing from one recording session to another. Another explanation, that he was named after cartoonist Ronald Searle's St. Trinian's character, "Flash Harry", is certainly wrong, since Sargent's nickname was current long before the first appearance of the St. Trinian's character in 1954. Sargent’s devoted fans the Prommers took the nickname and shortened it to “Flash”, though Sargent was not especially keen on the soubriquet even thus modified.[49]

Beecham made some well-recorded digs at Sargent. He quipped, in reference to the young conductor Herbert von Karajan, that he was "a kind of musical Malcolm Sargent"; and when he heard that Sargent was conducting in Tokyo, he punningly remarked, "Flash in Japan!".[50] However, Beecham conceded that Sargent "is the greatest choirmaster we have ever produced... he makes the buggers sing like blazes." And on another occasion, Beecham said that Sargent was "the most expert of all our conductors – myself excepted, of course."[51] Toscanini too regarded Sargent as the finest choral conductor in the world.[52] Even orchestral musicians gave him credit: the principal violist of the BBC Symphony Orchestra wrote of him, "He is able to instil into the singers a life and efficiency they never dreamed of. You have only to see the eyes of a choral society screwing into him like hundreds of gimlets to understand what he means to them."[53]

Although, for much of his career, orchestral players resented Sargent, instrumental soloists generally liked working with him. The cellist Pierre Fournier called him a "Guardian Angel" and compared him favourably with George Szell and Herbert von Karajan. Schnabel, Jascha Heifetz and Yehudi Menuhin thought similarly highly of him.[54] See also 'Concertos' in the Recordings section, below.

Memorials

Sargent was commemorated in a variety of ways. In 1968, the year after his death, the Proms began on a Friday evening rather than, as previously, a Saturday, and this has become a fixed practice. In memory of Sargent's choral work, a large-scale choral piece is customarily given. Beyond the world of music, a school and a charity were named after him: the Malcolm Sargent Primary School in Stamford and the Malcolm Sargent Cancer Fund for Children. The latter was established soon after his death in commemoration.[55] Merging with Cancer and Leukaemia in Childhood in 2005, it is now known as CLIC Sargent and is the UK's leading children’s cancer charity.[56]

Recordings

Sargent's composition, Impression on a Windy Day, has been recorded for CD by the Royal Ballet Sinfonia conducted by Gavin Sutherland on the ASV label. Sargent's first recordings as a conductor, made for HMV in 1923 using the acoustic process, were of excerpts from Vaughan Williams's opera Hugh the Drover. In the early days of electrical recording, he took part in a pioneering live recording of extracts of Mendelssohn's Elijah at the Albert Hall with the Royal Choral Society.[57]

Subsequently, in the recording studio, Sargent was most in demand in English music, choral works and as a conductor of concertos.

English music

- Coleridge-Taylor: Though the heyday of live performance at the Albert Hall was by then long gone Sargent, the Royal Choral Society and the Philharmonia made a stereo recording in the 1960s of Coleridge-Taylor's Hiawatha’s Wedding, which has been reissued on CD.

Painting based on The Beggar's Opera, William Hogarth, c. 1728

- Delius: Sargent and the Liverpool Philharmonic accompanied Albert Sammons, the dedicatee, in his 1944 recording of the Delius Violin Concerto. With Jacqueline du Pré in her début recording Sargent recorded Delius's Cello Concerto, coupled with the Songs of Farewell.

- Elgar: A recording regularly chosen over all others in comparative surveys is the first of Sargent’s two versions of Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius, with Heddle Nash as tenor and the familiar Sargent pairing of the Huddersfield Choral Society and the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra.[58] Sargent was the conductor for Jascha Heifetz's famous recording of the Violin Concerto.

- Gay: One of Sargent’s few operatic recordings other than Gilbert and Sullivan is of The Beggar's Opera, which has been reissued on CD.

- Holst: Sargent made two recordings of Holst's The Planets: a monaural version with the LSO for Decca and a stereo version with the BBC Symphony for EMI. He also recorded shorter Holst pieces: the Perfect Fool ballet music and the Beni Mora suite.

The Mikado

- Sullivan: Sargent conducted the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company recordings for HMV, including The Yeomen of the Guard (1929), The Pirates of Penzance (1929), Iolanthe (1930), H.M.S. Pinafore (1930), Patience (1930), Yeomen (excerpts 1931), Pirates (excerpts 1931), The Gondoliers (excerpts 1931), Ruddigore (1932) and Princess Ida (1932); and for Decca, more than thirty years later, Yeomen (1964) and Princess Ida (1965). Between 1957 and 1963 Sargent conducted nine of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas for EMI recordings using the Pro Arte Orchestra, the Glyndebourne Festival Chorus and soloists from the world of oratorio and grand opera. These wereTrial by Jury, Pinafore, Pirates, Patience, Iolanthe, The Mikado, Ruddigore, Yeomen and The Gondoliers. Sargent used an orchestra of 37 players at the Savoy (the same number as Sullivan) but sometimes added a few more when recording.[59]

- Vaughan Williams: Though he conducted the première of VW's Ninth and last symphony, Sargent did not record it. Of VW's shorter pieces, Sargent recorded the Tallis Fantasia, the Serenade to Music (choral version) and Toward the Unknown Region.

- Walton: A recording of Belshazzar's Feast, a Sargent speciality, was made in 1958 and reissued on CD in 1990 and again in 2004. Sargent made a stereo recording of Walton's First Symphony in the presence of the composer, but Walton privately preferred André Previn's recording[60] issued in the same month as Sargent's (January 1967).[61] Sargent also recorded the Façade Suites, but not Troilus and Cressida, of which he had conducted the première. On 78 r.p.m. discs William Primrose, the RPO and Sargent recorded Walton's Viola Concerto (of which Sargent later - 1962 - conducted the première of Walton's revised version).

Choral recordings

Sargent recorded Handel's Messiah three times. Though the advent of period performance at first relegated Sargent’s large scale and rescored versions to the shelf they have been reissued and are now attracting favourable critical comment as being, in their own way, historical. The same forces also recorded Handel's Israel in Egypt. and Mendelssohn's Elijah.

Concertos

Sargent was continually in demand as a conductor for concertos. In addition to the concertos noted above, among the other composers whose concertos he conducted on record are Bach, Bartók, Bliss, Bruch, Dvořák, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Rachmaninov, Rawsthorne, Rubbra, Schumann and Tchaikovsky. Soloists included Clifford Curzon, Pierre Fournier, Jascha Heifetz, Moura Lympany, Denis Matthews, David Oistrakh, Ruggiero Ricci, Max Rostal, Mstislav Rostropovich and Paul Tortelier.[62]

Other recordings

- Beethoven: Neville Cardus said of Sargent’s Beethoven "I have heard performances which critics would have raved about, had some conductor from Russia been responsible for them, conducting them half as well and truthfully."[63] Sargent was not invited to make many studio recordings of Beethoven, though his accompaniments for Artur Schnabel in the piano concertos have been admired. A stereo recording of the Eroica Symphony has been reissued on CD.

- Sibelius: Sargent was an enthusiastic champion of Sibelius’s music, even recording it with the Vienna Philharmonic when it was not part of their repertory. Their recordings of Finlandia, En Saga, The Swan of Tuonela and the Karelia Suite were issued in 1963 and reissued on CD in 1993. Sargent and the BBC Symphony Orchestra recorded the First and Fifth Symphonies (in 1956 and 1958 respectively) reissued on CD in 1989.

Notes

- ^ Ayer, p. 385

- ^ Aldous, p.12

- ^ Aldous, p.12

- ^ Ayer, p. 385

- ^ Reid, p.95

- ^ Reid, p.86

- ^ Aldous, p.23

- ^ Aldous, p.28 and Reid, p.104

- ^ Aldous, p.29

- ^ Reid, p.124

- ^ Reid, p.139-146 and Ayer, p.385

- ^ Reid, p.137

- ^ Reid, p.124 and Aldous, p.41

- ^ Reid, p.130

- ^ Aldous, p.42

- ^ Aldous, p.157

- ^ Reid, p.161

- ^ Aldous, p.60

- ^ Aldous, p.64

- ^ Reid, p.465

- ^ Morrison, p.78

- ^ Aldous, p.69

- ^ Reid, p.170

- ^ Reid, p.217

- ^ Reid, p.246

- ^ Aldous, p.98

- ^ Reid, p.282 and pp.309-31

- ^ Reid, pp.270-81 and Aldous, p.105

- ^ Aldous, p.107

- ^ Reid, p.278

- ^ Reid, p.340.

- ^ Lebrecht, p.157

- ^ Cox, p.349

- ^ Cox, pp.312-3

- ^ Reid, pp. 355-59

- ^ Reid, pp.433-34

- ^ Reid, p.487

- ^ Moore (pages not numbered)

- ^ Aldous p.239-45

- ^ Aldous, p.27 and Reid, p.98

- ^ Reid, p.251

- ^ Aldous, p.131

- ^ Lyttelton/Hart-Davis, 19 January 1958

- ^ Lyttelton/Hart-Davis, 20 November 1955 fn

- ^ Aldous, p. 124

- ^ Lyttelton/Hart-Davis, 19 January 1958

- ^ Reid, p.129

- ^ Reid, p.4

- ^ Reid, p.394-393

- ^ Reid, p.395

- ^ Reid, p.202 and Daily Mirror

- ^ Aldous, p.97

- ^ Shore, p.153

- ^ Aldous, p.xi

- ^ Prestwick golf course for the Malcolm Sargent Cancer Fund for Children - 25 October 2004 scottish-enterprise.com/sedotcom - Retrieved: 29 May 2007

- ^ BBC News coverage about merger of Cancer Funds - 3 November, 2004 bbc.co.uk - Retrieved: 29 May 2007

- ^ The Gramophone

- ^ BBC Radio 3 'Building a Library'

- ^ Ayer, p. 385

- ^ Kennedy p. 213

- ^ The Gramophone, January 1967

- ^ Mirror tribute, discography

- ^ Obituary notice, The Guardian, 4 October 1967, quoted by Reid

References

- Aldous, Richard (2001). Tunes of glory: the life of Malcolm Sargent. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0091801311.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Ayre, Leslie (1972). The Gilbert & Sullivan Companion. Introduction by Martyn Green. London: W.H. Allen & Co Ltd. ISBN 0396066348.

- Cox, David (1980). The Henry Wood Proms. London: BBC. ISBN 0563176970.

- Discography in Sir Malcolm Sargent: a tribute (1967). London: Daily Mirror Newspapers.

- The Gramophone, November 1967, p. 253.

- Hart-Davis, Rupert, (ed) (1981). The Lyttelton Hart Davis Letters. London: John Murray. pp. vol. 1, 3. ISBN 0719542901.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kennedy, Michael (1989). Portrait of Walton. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0193154188.

- Lebrecht, Norman (2001). The Maestro Myth: Great Conductors in Pursuit of Power (revised ed. ed.). New York: Citadel Press. ISBN 0806520884.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Moore, Jerrold Northrop (1982). Philharmonic. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0091473004.

- Morrison, Richard (2004). Orchestra. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 057121584X.

- Reid, Charles (1968). Malcolm Sargent a biography. London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd. ISBN 0241913160.

- Sargent, Malcolm (1962). The Outline of Music. London: Arco Publishing. OCLC 401043.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Shore, Bernard (1938). The Orchestra Speaks. London: Longmans.

External links

- Sargent Malcolm Sargent at AllMusic

- Please use a more specific IMDb template. See the documentation for available templates.

- Malcolm Sargent Biography, photos.

- Malcolm Sargent short biography at the Who Was Who in the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company website

- CD Review Building a Library from BBC Radio 3

- Book review of 2001 Aldous biography at musicweb

- Malcolm Sargent at MusicBrainz

- Malcolm Sargent profile at the Memories of the D'Oyly Carte website

- Correspondence from Sargent at the Morrison Foundation

- Analysis of Sargent's G&S tempi in the 1930s as compared with the 1960s

- Leicester Symphony Orchestra