History of Central Asia

The history of Central Asia is defined by the area's climate and geography. The aridness of the region made agriculture difficult and its distance from the sea cut it off from much trade. Thus few major cities developed in the region, rather for millennia the area was dominated by the nomadic horse peoples of the steppe.

Relations between the steppe nomads and the settled people in and around Central Asia were long marked by conflict. The nomadic lifestyle was well suited to warfare and the steppe horse riders became some of the most militarily potent peoples in the world, only limited by the lack of internal unity. Periodically great leaders or changing conditions would organize several tribes into to one force, and create and almost unstoppable power. These included the Hun invasion of Europe, the Wu Hu attacks on China and most notably the Mongol conquest of much of Eurasia. When the area was unified it became the centre of overland trade routes, most prominently the Silk Road, which brought prosperity and foreign ideas to the region.

The dominance of the nomads ended in the sixteenth century, as firearms allowed settled peoples to gain control of the region. Most notably Russia expanded through the region and had captured the bulk of Central Asia by the end of the nineteenth century. After the Russian Revolution the Central Asian regions were incorporated into the Soviet Union. The Soviet period saw much industrialization and construction of infrastructure, but it also saw the suppression of local cultures, hundreds of thousands of deaths from failed collectivization programs, and a lasting legacy of ethnic tensions and environmental problems.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union five countries gained independence. In all the states former Communist Party officials retained power as local strongmen. In no state is repression as great as it was in Soviet times, but none of the new republics could be considered functional democracies.

Prehistory

Recent genetic studies have identified this region as the likeliest source of the men who later inhabited Europe, for Central Asians display much more genetic variety than Europeans but share the same genetic markers. As such, this region may be one of the oldest sites of human habitation. (The archaeological evidence of human habitation in this region is lacking, however, whereas evidence of human habitation in Africa and Australia prior to that of Central Asia is well-known.) The region is also often considered to be the source of the root of the Indo-European languages.

The domestication of the horse began in Central Asia in the fourth millennium BC. The horse s were bred for strength, and by the second millennium BC they were strong enough to pull chariots. This gave rise to nomadism, a way of life that would dominate the region for the next several millennia.

Scattered nomadic groups maintained herds of sheep, goats, horses, and camels, and conducted annual migrations to escape the winter snows (a practice known as transhumance). The people lived in gers, tents made of hides and woods that could be disassembled and transported. Each group had several ger, accommodating about five persons each.

The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex of the early second millennium BC was the first sedentary civilization of the region, practicing irrigation farming of wheat and barley and possibly a form of writing. Bactria-Margiana probably interacted with the contemporary Bronze Age nomads of the Andronovo culture, the originators of the spoke-wheeled chariot, who lived to their north in western Siberia, Russia, and parts of Kazakhstan, and survived as a culture until the first millennium BC. These cultures, particularly Bactria-Margiana, have been posited as possible representatives of the hypothetical Aryan culture ancestral to the speakers of the Ural-Altaic and Indo-Iranian languages.

While the semi-arid plains were dominated by the nomads small city-states and sedentary agrarian societies arose in the more humid areas of Central Asia. The most important area was the string of Sogdian city states in the Fergana Valley. After the first century BC these cities became home to the traders of the Silk Road and grew wealthy from this trade. The steppe nomads were dependent on these settled people for a wide array of goods that were impossible for transient populations to produce. The nomads traded for these when they could, but because they generally did not produce goods of interest to sedentary peoples the popular alternative was to carry out raids.

A wide variety of people's came to populate the steps. Nomadic groups in Central Asia eventually included the Xiongnu (Huns) and other Turkic peoples, the Yuezhi (Tocharians or Kushans), the Persians and other Indo-European peoples, and the Mongols.

External influences

Around the southern periphery developed a series of large and powerful states. There were several attempts to conquer the steppe peoples with only mixed success. The Median empire and Achaemenid empire both ruled parts of Central Asia. Chinese states would also regularly strive to extend their power westwards. However, these strong states found it almost impossible to conquer the nomads despite outmatching them militarily. There were few cities to occupy and when faced by a stronger force the nomads could simply retreat into the steppe. Herodotus gives a detailed account of the futile Persian campaigns and against the Scythians. Moreover the region had little wealth, except the herds that would disappear with the retreating nomads.

Alexander the Great's conquests spread Hellenistic civilization all the way to Alexandria Eschate (Lit. “Alexandria the Furthest”), established in 329 BC in modern Tajikistan. After Alexander's death in 323 BC, the Central Asian successor satraps of his territory fell to the Seleucid Empire during the Wars of the Diadochi. In 250 BC, the Central Asian portion of the empire (Bactria) seceded as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, which had extensive contacts with India and China till its end in 125 BC. The Indo-Greek Kingdom, mostly based in India but controlling a fair part of Afghanistan, pioneered the development of Greco-Buddhism. The Kushan Kingdom thrived across a wide swath of the region from the Second Century BC to the Fourth Century AD, and continued Hellenistic and Buddhist traditions. These states prospered from their position on the Silk Road linking China and Europe. Later, external powers such as the Parthian Empire and Sassanid Empire would come to dominate this trade.

Over time, the nomadic horsemen grew in power. New technologies were introduced. The Scythians developed the saddle, and by the time of the Alans the use of the stirrup had begun. Horses continued to grow larger and sturdier. Chariots were no longer needed as the horses could carry men with ease. This greatly increased the mobility of the nomads; it also freed their hands, allowing them to use the bow from horseback. Using small but powerful composite bows, the steppe people gradually became the most powerful military force in the world. From a young age almost the entire male population was trained in riding and archery, both of which were necessary skills for survival on the steppe. By adulthood these activities were second nature. These mounted archers were more mobile than any other force at the time, being able to travel 40 miles a day with ease. The steppe people quickly came to dominate Central Asia, forcing the scattered city states and kingdoms to pay them tribute or face annihilation. The Hephthalites were the most powerful fo these nomad groups in the sixth and seventh century and controlled much of the region.

This martial ability of the steppe peoples was limited, however, by the lack of political structure within the tribes. Confederations of various groups would sometimes form under a ruler known as a khan. Tradition was that any such dominion should be divided among all of the khan's sons, and these dominions thus declined as quickly as they formed. When large numbers of nomads acted in unison they could be devastating, as when the Huns arrived in Western Europe or when a number of different groups raided China.

As this time Central Asia was a heterogeneous region that saw a mixture of the cultures and religions of the rest of Eurasia. Buddhism remained the largest religion, but around Persia Zoroastrianism became important. Nestorian Christianity entered the area, but was never more than a minority faith. More successful was Manichaeism, which became the third largest faith. Many practiced more than one faith, and almost all of the local religions were infused with local shamanistic traditions. In the eighth century, Islam began to penetrate the region. It was far less accommodating, and soon Islam was the sole faith of most of the population, though Buddhism remained strong in the east. The desert nomads of Arabia could militarily match the nomads of the steppe, and so the early Arab dynasties gained control over parts of Central Asia. The Arab invasion also saw Chinese influence expelled from western Central Asia. At the Battle of Talas and Arab army decisively defeated a Tang Dynasty force and for the next several centuries Middle Eastern influences would dominate the region.

Return of indigenous rule

Autochthonous groups soon re-emerged and set up states in Central Asia, including dominions that spread beyond the area, such as the Samanid dynasty, that of the Seljuk Turks, and Khwarezm.

The most spectacular power to rise out of Central Asia developed when Temujin (Genghis Khan) united the tribes of Mongolia. Using superior military techniques, the Mongol Empire spread to comprise huge areas of Central Asia, as well as large parts of China, Russia, and the Middle East. After Temujin, most of Central Asia continued to be dominated by the successor Chagatai Khanate. This state proved to be short lived as in 1369 Tamerlane, a Turkic leader in the Mongol military tradition, conquered most of the region.

While the steppe peoples of Central Asia found conquest easy, they found governing almost impossible. The diffuse political structure of the steppe confederacies was maladapted to the complex states of the settled peoples. Moreover, the armies of the nomads were based upon large numbers of horses, generally three or four for each warrior. Maintaining these forces required large stretches of grazing land, not present outside the steppe. Thus, any extended time away from the homeland would cause the steppe armies to gradually disintegrate. To govern settled peoples the steppe nomads were forced to rely on the local bureaucracy, a factor that lead to the rapid assimilation of the steppe peoples into the culture of those they had conquered. The armies, for the most part, were unable to penetrate the forested regions to the north; thus, such states as Novgorod and Muscovy began to grow in power.

The Conquest of the Steppes

The lifestyle that had existed largely unchanged since 500 BC began to disappear after 1500. An important change in the world economy in the fourteenth and fifteenth century was brought about by the development of nautical technology. Nautical transportation routes were pioneered by the European traders, who were cut off from the "Silk Road" by the Muslim states that controlled it western termini. The breakdown in organized government in the region after the end of the Mongol period also made trade and travel far more difficult and the "Silk Road" went into steep decline. The trade between East Asia, India, Europe, and the Middle East went over the seas and not through Central Asia, causing the prosperity of the area to sharply decline.

A more important development was the introduction of gunpowder-based weapons. The gunpowder revolution allowed settled peoples to defeat the steppe horsemen in open battle for the first time. Construction of these weapons required the infrastructure and economy of large societies, and the nomads were unable to match them. For the first time, the domain of the nomads began to shrink. In a gradual process beginning in the fifteenth century The Russians expanded south, as the Ukraine became an agricultural heartland. The Chinese spread west, and the British in India, north.

China had controlled much of East Turkestan during earlier parts of its history. In the eighteenth century the Manchu emperors, themselves from the far east edge of the steppe, campaigned in the west and in Mongolia with the Qianlong Emperor taking control of Xinjiang in 1758. The Mongol threat was overcome and much of Inner Mongolia was annexed to China.

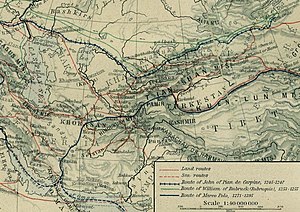

The slow Russian conquest of the heart of Central Asia began in the early nineteenth century, although Peter the Great had sent a failed expedition under Prince Bekovitch-Cherkassky against Khiva as early as the 1720s. By the 1800s, the locals could do little to resist the Russian advance, although the Kazakhs under Kenesary Kasimov rose in the 1820s-30s. Until the 1870s, for the most part, Russian interference was minimal, leaving native ways of life intact and local government structures in place. With the conquest of Turkestan after 1865 and the consequent securing of the frontier, the Russians gradually expropriated large parts of the steppe and gave these lands to Russian farmers, who began to arrive in large numbers. This process was initially limited to the northern fringes of the Steppe, and it was only in the 1890s that significant numbers of Russians began to settle farther south, especially in Semirechie. The locals could do little to resist the advance of the Tsars' armies. The main opposition to Russian expansion came from the British who feared Russian encroachment on India. This set off The Great Game where both powers competed to advance their own interests in the region.

The Conquest of Turkestan

After the fall of Tashkent to General Cherniaev in 1865, Khodjend, Djizak, and Samarkand fell to the Russians in quick succession, as the Khanate of Kokand and the emirate of Bukhara were repeatedly defeated. In 1867 the Governor-Generalship of Russian Turkestan was established, with its headquarters at Tashkent, under General Konstantin Petrovich Von Kaufman. In 1881-85 the Transcaspian region was annexed in the course of a campaign led by Generals Annenkov and Skobelev, and Ashkhabad, Merv and Pendjeh all came under Russian control. Russian expansion was halted in 1887 when Russia and Great Britain delineated the northern border of Afghanistan. Bukhara and Khiva remained quasi-independent, but were essentially protectorates along the lines of the Princely States of British India. Although the conquest was prompted by almost purely military concerns, in the 1870s and 1880s Turkestan came to play a reasonably important economic role within the Russian Empire. Because of the American Civil War, cotton shot up in price in the 1860s; this became an increasingly important commodity in the region, although its cultivation was on a much lesser scale than during the Soviet period. The cotton trade led to improvements: the Transcaspian Railway from Krasnovodsk to Samarkand and Tashkent, and the Trans-Aral Railway from Orenburg to Tashkent were constructed. In the long term the development of a cotton monoculture would render Turkestan dependent on food imports from Western Siberia, and the Turkestan-Siberia Railway was already planned when the First World War broke out. Russian rule still remained distant from the local populace, mostly concerning itself with the small minority of Russian inhabitants of the region. The local Muslims were not considered full Russian citizens. They did not have the full privileges of Russians, but nor did they have the same obligations, such as military service. The Tsarist regime left substantial elements of the previous regimes (such as Muslim religious courts) intact, and local self-government at the village level was quite extensive.

During the First World War the Muslim exemption from conscription was removed, sparking the Central Asian Revolt of 1916. When the Russian Revolution occurred, the Turkestan Muslim Council met in Kokand and declared Turkestan's autonomy. This new government was quickly crushed by the Red Army, and the semi-autonomous states of Bukhara and Khiva were also invaded. The main independence forces were rapidly crushed, but guerrillas known as basmachi continued to fight the Communists until 1924.

The Chinese Civil War also saw Turkic nationalist make attempts at independence. In 1933 the First East Turkistan Republic was declared, but it was destroyed soon after with support from the Soviets who feared the independence movement would spread. A decade later the Second East Turkistan Republic was formed, this time with Soviet backing and allied with the Communists. This state was annexed into the People's Republic of China in 1949.

Soviet domination

In 1918 the Bolsheviks set up the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, and Bukhara and Khiva also became SSRs. In 1919 the Conciliatory Commission for Turkestan Affairs was established, to try to improve relations between the locals and the Communists. New policies were introduced, respecting local customs and religion. In 1920 the Kirghiz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, covering modern Kazakhstan, was set up. It was renamed the Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in 1925. In 1924, the Soviets created the Uzbek SSR and the Turkmen SSR. In 1929 the Tajik SSR was split from the Uzbek SSR. The Kirghiz Autonomous Oblast became an SSR in 1936.

These borders had little to do with ethnic makeup, but the Soviets felt it important to divide the region. They saw both Pan-Turkism and Pan-Islamism as threats, which dividing Turkestan would limit. Under the Soviets, the local languages and cultures were systematized and codified, and their differences clearly demarcated. New Cyrillic writing systems were introduced, to break links with Turkey and Iran. Under the Soviets the southern border was almost completely closed and all travel and trade was directed north through Russia.

Under Stalin at least a million persons died, mostly in the Kazakh SSR, during the period of forced collectivization. Islam was also attacked. In the Second World War several million refugees and hundreds of factories were moved to the relative security of Central Asia; and the region permanently became important part of the Soviet industrial complex. Several important military facilities were also located in the region, including nuclear testing facilities and the Baikonur Cosmodrome. The Virgin Lands Campaign, starting in 1954, was a massive Soviet agricultural resettlement program that brought more than 300,000 individuals, mostly from the Ukraine, to the northern Kazakh SSR and the Altai region of the Russian SFSR. This was a major change in the ethnicity of the region. Since the 1950s, there has also been major Han Chinese migration to Eastern Turkestan, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia in the PRC.

Since 1991

From 1988 to 1992 a free press and multiparty system developed in the Central Asian republics as perestroika pressured the local Communist parties to open up. What Svat Soucek calls the "Central Asian Spring" was very short-lived, however. Soon after independence former Communist Party officials recast themselves as local strongmen. In no state has repression been as great as it was in Soviet times, but none of the new republics could be considered functional democracies. Political stability in the region has mostly been maintained, with the major exception of the Tajik Civil War that lasted in from independence to 1997. 2005 also saw the largely peaceful ouster of Kyrgyz president Askar Akayev in the Tulip Revolution and an outbreak of violence in Uzbekistan that left several people dead.

Much of the population of the region was indifferent to the collapse of the Soviet Union. Large percentages of the local populations are Russian, especially in Kazakhstan, and they had no interest in independence. Aid from the Kremlin had also been central to the economies of Central Asia, each of the republics receiving massive transfers of funds from Moscow. Independence largely resulted from the efforts of the small groups of nationalistic, mostly local intellectuals, and from a little in Moscow to retain the expensive region.

While never a part of the Soviet Union, Mongolia followed a somewhat similar path. Freed from Soviet domination, it shed the communist system in 1996, but quickly ran into economic problems. See: History of independent Mongolia.

The economic performance of the region since independence has been mixed. It contains some of the largest reserves of natural resources in the world, but there are important difficulties in transporting them. Since it lies farther from the ocean than does anywhere else in the world, and its southern borders lay closed for decades, the main trade routes run through Russia. As a result, Russia still exerts a significant influence over the region, more truly than in other former Soviet republics. Increasingly, other powers have begun to involve themselves in Central Asia. The People's Republic of China sees the region as an essential future source of raw materials; most Central Asian countries are members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. China also sees a threat, in the potential of these states to support separatist movements among its own Turkic minorities. Turkey has also begun to look east, and a number of organizations are attempting to build links between the western and eastern Turks. Iran, which for millennia had close links with the region, has also been working to build ties, and the Central Asian states trade, and enjoy good relations, with this Islamic Republic.

One important player in the new Central Asia has been Saudi Arabia, which has been funding the Islamic revival in the region. Soon after independence, Saudi money paid for massive shipments of Qur'ans to the region and for the construction and repair of a large number of mosques. In Tajikistan alone, it is estimated that 500 mosques a year have been erected with Saudi money. The formerly atheistic Communist Party leaders have mostly converted to Islam. Small Islamist groups have formed in several of the countries, but radical Islam has little history in the region; the Central Asian societies have remained quite secular, and all five states enjoy good relations with Israel. Central Asia is still home to some 200,000 Jews, and important trade and business links have developed between those that left for Israel and those remaining.

One important Soviet legacy that has only gradually been appreciated is the vast ecological destruction. Most notable is the gradual drying of the Aral Sea. During the Soviet era, it was decided that the traditional crops of melons and vegetables would be replaced by water-intensive growing of cotton for Soviet textile mills. Massive irrigation efforts were launched that diverted a considerable percentage of the annual inflow to the sea, causing it to shrink steadily. Furthermore, vast tracts of Kazakhstan were used for nuclear testing, and there exists a plethora of decrepit factories and mines.

See also

References & Further Reading

- Barthold, V.V. Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion (London) 1968 (Third Edition)

- Brower, Daniel Turkestan and the Fate of the Russian Empire (London) 2003

- Dani, A.H. and V.M. Masson eds. UNESCO History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Paris: UNESCO, 1992-

- Sinor, Dennis The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia (Cambridge) 1990 (2nd Edition)

- Soucek, Svat A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- В.В. Бартольд История Культурной Жизни Туркестана (Москва) 1927

- Н.А. Халфин Россия и Ханства Средней Азии (Москва) 1974