Jazz drumming

Jazz drumming is the art of playing percussion (predominantly the drum set) in jazz. The techniques and instrumentation of this type of performance have evolved over several periods, influenced by jazz at large and the individual drummers within it. Stylistically, this aspect of performance was shaped by its starting place, New Orleans,[1] as well as numerous other regions of the world, including other parts of the United States, the Caribbean, and Africa.[2]

Due to the necessity of drumming in the early developmental era of jazz, a different method of playing percussion was invented, that of jazz drumming.[3] Jazz drummers continued to move their music through the decades of the 20th century, expanding and elaborating on previously created themes and ideas. Periods of jazz like swing, bebop, etc., are defined by the rhythms that were played by the drummer and in the piece as a whole, as jazz is fundamentally based on rhythmic structures.

The style could have begun at a number of different times, and the borders between the periods of its development are very rough. Influence resulting from the mix of music and technique of various cultures, musicians' and industrial innovation in performance technology, and the spread of jazz throughout the United States, and later the world, were major factors.

Early history

Preliminary cultural mixing

The rhythms and use of percussion in jazz, as well as the art form itself, were products of extensive cultural mixing in various locations. The earliest occasion when this occurred was the Moorish invasion of Europe, where the cultures of France, Spain, and Africa to some extent, encountered each other and most likely exchanged some cultural information.[1] The influence of African music and rhythms on the general mix that created jazz was profound, though this influence did not appear until later.

African influence

There are several central qualities shared by African music and jazz, most prominently the importance of improvisation.[1] Some instrumental qualities from African music that appear in jazz (especially its drumming) include using unpitched instruments to produce specific musical tones or tone-like qualities, using all instruments to imitate the human voice[2], superimposition of one rhythmic structure onto another (e.g., a group of three against a group of two), dividing a regular section of time (called a measure in musical terms) into groups of two and three, and the use of repetitive rhythms used throughout a musical piece, often called clave rhythms.[4] This last quality is one of special importance, as there are several pronounced occurrences of this pattern and the aesthetics that accompany it in the world of jazz.

The clave

Template:Sound sample box align right

Template:Sample box end The clave (IPA: ˈkla ve) is integral to Caribbean music as well, because African slaves were brought to the Caribbean islands, particularly Cuba. The clave functions as a tool for the musicians of these cultures to keep time as well as determine which beats in a composition should be accented. In Africa, the clave is based on division of the measure into groups of three, on which only a few of the beats are accented. The Cuban clave, derived from the African version, (of which there are several variations) is composed of two measures of 4/4 time, one with three beats, one with two. The measures can be played in either order, with the two or three beat phrase coming first. Apart from this small flexibility, the musical element has several very strict rules regarding its use. For a piece to be “in clave”, all accented notes must be either on the beats of the clave or, if not, be equalized by accents on the clave beat; the notes of the piece must alternate between syncopated (off-beat) and non-syncopated (on-beat) phrases depending on which measure was placed first (see also Back beat); and, if the clave is originally off but resolves itself, the piece may still be considered to be in clave.[5] Clave rhythms are either labeled “2-3” or “3-2”, depending on which measure is first.

Within the rhythm section, phrases known as “comping patterns” have included elements of the clave since the very early days of the music.[5] The term “comping” comes from the words “accompany” and “complement”, and, in terms of how it applies to music, comping is support of other musicians, often soloists, and echoing or reinforcement of the composition. A phrase known as “The Charleston” is a common example of an application of the clave in jazz, specifically comping. It is a pattern almost identical to that of the two beat measure of the son clave, one version of the clave from Cuba. Another method of integrating the clave with jazz is to rephrase a composition rhythmically to correspond with the clave.

Cuban influence

The culture that created the most commonly used version of this pattern was that of Cuba. The circumstances that created that music and culture were very similar to those that created jazz. French, African, Spanish, and native Cuban cultures were all combined in Cuba and created many popular Cuban musical forms as well as the clave, which was a rather early invention. Though Caribbean and African influences supplied much of the backbone of jazz, the military and other musical aspects of the European culture made many of the percussive elements and rhythms possible as well.

American influence

The military drumming of America, predominantly fife and drum corps, in the 1800s and earlier supplied much of the technique and instrumentation of the early jazz drummers. Influential players like Warren “Baby” Dodds and Zutty Singleton used the traditional military drumstick grip, military instruments, and played in the style of military drummers, using rudiments, a group of short patterns which are standard in drumming.[2] The rhythmic composition of this music was also important in early jazz and beyond. Very different from the African performance aesthetic, a flowing style which does not directly correspond to Western time signatures,[4] the music played by military bands was rigidly within time and metric conventions, though it did have compositions in both duple and triple meter. The equipment of the drummers in these groups was of particular significance in the development of early drum sets. Cymbals, bass, and snare drums were all used. Indeed, a method of dampening a set of cymbals by crunching them together while playing bass drum simultaneously is probably how today’s hi-hat, a set of cymbals which can be set as closed or open, came about.[2] Military technique and instrumentation were undoubtedly factors in the development of early jazz and its drumming, but the melodic and metric elements in jazz are more easily traced to the dance bands of the time period.

Dance bands

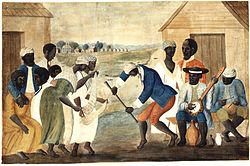

Black drummers were able to acquire their technical ability from fife and drum corps,[2] but the application of these techniques in the dance bands of the 1800s allowed a more fertile ground for musical experimentation. Slaves learned traditional European dance music that they played at their masters’ balls, most importantly a French dance called the quadrille, which had a particular influence on jazz and by extension jazz drumming. Musicians were also able to play dances that originated in Africa and the Caribbean in addition to the European repertoire. One such dance was the “congo”.[2] The performers of this novel music (to the predominantly white audience) created music for their own entertainment and uses as well.

Slave traditions

Slaves in America had many musical traditions that became very important to the music of the country, particularly jazz. The work song was one of these traditions, an improvised system of singing based off the idea of call and response, a central aspect of African music. There were also several instrumental improvisation techniques that were used: after work was done, these people would hold musical performances in which they played on pseudo-instruments made of wash-tubs and other objects newly used for musical purposes, and also played rhythms on their bodies, called “pattin’ juba”.[2] The only area that slaves were allowed to perform their music, other than private locations, was a place in New Orleans called Congo Square.[1]

Congo Square and New Orleans

The decision to allow this type of performance was a very unusual one for the city’s government to make, as all other regions had instituted very restrictive laws regarding the musical performance of slaves, and even New Orleans had legislation that eliminated essentially every other aspect of the African culture. Nevertheless, the former Africans were able to play their traditional music, which started to intermingle with the sounds of the many other cultures in New Orleans at the time: Haitian, European, Cuban, and American, as well as many other smaller denominations. However, the people playing in Congo Square were not of the younger generation, the one traditionally associated with innovation and new attitudes toward mixing culture, but older musicians. They used drums almost indistinguishable from those made in Africa, though the rhythms were somewhat different from those of the songs of the regions the slaves were from, probably the result of their having lived in America for several generations. Because of the extensive exposure that Congo Square performance had in New Orleans and the differences noted between it and traditional West African song, this location is regarded as the birthplace of jazz in New Orleans.

Blues

Of course, there was an important influence to jazz that has been neglected thus far: the blues. The work song was the celebration of work, a joyous song. The blues, obviously from its name, was exactly the opposite. It was an expression of the hardships experienced daily by slaves, and its musical inspiration came from where its players did, Africa. The rhythmic form of blues was a basis for many developments that would appear in jazz. Though its instrumentation was mostly limited to melodic instruments and a singer, feeling and rhythm were tremendously important. The two primary feels were a syncopated pulse on beats two and four that we see in countless other forms of American music, and the shuffle, which is essentially the pattin’ juba rhythm, a feel based on a division of three rather than two.[6]

Second line

One of the final influences on the development of early jazz, specifically its drumming and rhythms, was Second line drumming. The term “Second line” refers to the literal second line of musicians that would often congregate behind a marching band playing at a funeral march or Mardi Gras celebration. There were usually two main drummers in the second line: bass and snare players. The rhythms played were improvisatory in nature, but similarity between what was played at various occasions came essentially to a point of consistency, and early jazz drummers were able to integrate patterns from this style into their playing, as well as elements from several other styles.[7]

Ragtime

Before jazz came to prominence, drummers often played in a style known as ragtime, where an essential rhythmic quality of jazz first really began to be used: syncopation. Syncopation is synonymous with being “off-beat”, and it is, among many things, a result of placing African rhythms written in odd combinations of notes (e.g., 3+3+2) into the evenly divided European metric concept.[5] Ragtime was another style derived from black musicians playing European instruments, specifically the piano, but using African rhythms.

Modern jazz drumming

Early technique and instrumentation

The first truly jazz drummers had a somewhat limited palette from which to draw , despite their apparent broad range of influence. Military rudiments and beats in the military style were essentially the only technique that they had at their disposal. However, it was necessary to adapt to the particular music being played, so new technique and greater musicianship evolved. The roll was the major technical device used, and one significant pattern was simply rolling the length of a quarter note (1/4 of a measure) on beats one and three.[3] This was one of the first “ride patterns”, a series of rhythms that eventually resulted in a beat that functions in jazz as the clave does in Cuban music: a “mental metronome” for the other members of the ensemble. Warren “Baby” Dodds, one of the most famous and important of the second generation of New Orleans jazz drummers. Dodds stressed the importance of drummers playing something different behind every chorus. His style was regarded as overly busy by some of the older generation of jazz musicians such as Bunk Johnson. Beneath the constant rhythmic improvisation, Dodds played a pattern that was only somewhat more sophisticated than the basic one/three roll, but it was, in fact, identical to the rhythm of today, only inverted. The rhythm was as follows: two “swung” eighth notes (the first and third notes of an eighth note triplet), a quarter note, and then a repeat of the first three beats. Aside from these patterns, a drummer from this time would have an extremely small role in the band as a whole. Drummers seldom soloed, as was the case with all other instruments in earliest jazz, which was based heavily on the ensemble. When they did, the resultant performance sounded more like a marching cadence than personal expression.[3] (Listen for example to Dodds on "Billy Goat Stomp" with Jelly Roll Morton's Red Hot Peppers in 1927.) Most other rhythmic ideas came from ragtime and its precursors, like the dotted eighth note series.

1900s to 1940s

The drummers and the rhythms they played served as accompaniment for dance bands, which played ragtime and various dances, with jazz coming later. It was common in these bands to have two drummers, one playing snare drum, the other bass. Eventually, however, due to various factors (not the least of which being the financial motivation), the number of drummers was reduced to one, and this created the need for a percussionist to play multiple instruments, hence the drum set. The first drum sets also began with military drums, though various other accessories were added later in order to create a larger range of sounds, and also for novelty appeal. The most common of the accoutrements were the wood block, Chinese tom-toms (large, two-headed drums), cowbells, cymbals, and almost anything else the drummer could think of adding. The characteristic sound of this set-up could be described as “ricky-ticky”: the noise of sticks hitting objects that have very little resonance.[2] However, drummers, including Dodds, centralized much of their playing on the bass and snare drums.[8] By the 1920s and ‘30s, the early era of jazz was ending, and swing drummers like Gene Krupa, Chick Webb, and Buddy Rich began to take the bases laid down by the early masters and experiment with them. It was not until a bit later, however, that the displays of technical virtuosity by these men were replaced by definite change in the underlying rhythmic structure and aesthetic of jazz, moving on to an era called bebop.

Bebop

To a small extent in the swing era, but most strongly in the bebop period, the role of the drummer evolved from an almost purely time-keeping position to that of a member of the interactive musical ensemble. Using the clearly defined ride pattern as a base, which was brought from the previous rough quality to the smooth, flowing rhythm we know today by “Papa” Jo Jones,[9] as well as a standardized drum set,[8] drummers were able to experiment with comping patterns and subtleties in their playing. One such innovator was Sidney “Big Sid” Catlett. His many contributions included comping with the bass drum, playing “on top of the beat” (imperceptibly speeding up), playing with the soloist instead of just accompanying him, playing solos of his own with many melodic and subtle qualities, and incorporating melodicism into all of his playing.[10] Another influential drummer of bebop was Kenny Clarke, the man who switched the four beat pulse that had previously been played on the bass drum to the ride cymbal, effectively making it possible for comping to move forward in the future.[11] Once again, this time in the late 1950s and most of the 60s, drummers began to change the entire basis of their art. Elvin Jones, in an interview with Down Beat magazine, described it as “a natural step”.[12]

1950s and 1960s

During this time, the drummer took on an even more influential role in the jazz group at large, and started to free the drums into a more expressive instrument, allowing them to attain more equality and interactivity with the other parts of the ensemble. In bebop, comping and keeping time were two completely different requirements of the drummer, but afterward, the two became one entity. This newfound fluidity greatly extended the improvisatory capabilities that the drummer had.[13] The feel in jazz drumming of this period was called “broken time”, which gets its name from the idea of changing patterns that had previously been rigid. The repetitive nature of the ride pattern and the steady pulse of the hi-hat on beats two and four were almost eliminated. Rhythm sections, in particular those of John Coltrane and Miles Davis, were also exploring new metric and rhythmic possibilities. The concept of manipulating time, making the music appear to slow down or race ahead, was something that drummers had never attempted previously, but one that was evolving quickly in this era. Layering rhythms on top of each other (a polyrhythm) to create a different texture in the music, as well as using odd combinations of notes to change feeling, would never have been possible with the stiffness of drumming in the previous generation. Compositions from this new period required this greater element of participation and creativity on the part of the drummer. Elvin Jones, a member of John Coltrane’s quartet, developed a novel triplet-based polyrhythmic style partly due to the fact that Coltrane’s pieces of the time were based on triple subdivision.[12] Also, because of the greater space in this new style both rhythmically and harmonically, greater experimentation was much easier to attain. Musicians were not encumbered by as many aspects of bebop, like the extremely high tempos and quick chord changes.

Free jazz

It seems that the evolution of jazz drumming has much to do with progressively “freeing” the beat, from swing to bebop, from bebop to post-bop. In avant-garde and free jazz, the beat was totally freed. A drummer named Sunny Murray is the primary architect of this new approach to drumming. Instead of playing a “beat”, Murray sculpts his improvisation around the idea of a pulse, and plays with “…the natural sounds that are in the instrument, and the pulsations that are in that sound”.[14] Murray also notes that his creation of this style was due to the need for a newer kind of drumming to use in the compositions of pianist Cecil Taylor.[14]

References

- ^ a b c d Gioia, T. (1997). The History of Jazz. Oxford University Press: New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-19-512653-2

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brown, T, D. (1976). A History and Analysis of Jazz Drumming to 1942. University Microfilms: Ann Arbor, MI.

- ^ a b c Brown, T, D. (1969). The Evolution of Early Jazz drumming. Percussionist, 7(2), 39-44.

- ^ a b Foundation Course in African Dance-Drumming Web site. (1995). Ladzekpo, C. Retrieved November 6, 2007, from http://cnmat.berkeley.edu/~ladzekpo

- ^ a b c Washburne, C. (1997). The Clave of Jazz: A Caribbean Contribution to the Rhythmic Foundation of an African-American music. Black Music Research Journal, 17(1), 59-71.

- ^ The beat of the blues. (2003). Retrieved November 3, 2007, from http://www.pbs.org/theblues/classroom/defbeat.html

- ^ Lambert, J. (1981). Second line drumming. Percussive Notes, 19(2), 26-28.

- ^ a b Riley, J. (1994). The art of bop drumming. Manhattan Music, Inc: Miami, FL. ISBN 0-89898-890-X

- ^ Pias, E. The Recorded History of Jazz Drumming. Retrieved November 3, 2007, from http://www.pd.org/~zeug/perf25/drumming.html

- ^ Hutton, J, M. (1991). Sidney "Bid Sid" Catlett: The Development of Modern Jazz Drumming Style. Percussive Notes, 30(1), 14-17.

- ^ Kenny Clarke. PBS JAZZ – A Film by Ken Burns. Retrieved November 3, 2007, from http://www.pbs.org/jazz/biography/artist_id_clarke_kenny.htm

- ^ a b (1963). Elvin Jones: The Sixth Man. Down Beat. Retrieved December 6, 2007, from http://www.downbeat.com/default.asp?sect=magazine

- ^ Riley, J. (2006). Beyond bop drumming. Alfred Publishing Co., Inc: Van Nuys, CA. ISBN 978-1576236093

- ^ a b Allen, C. (2003). Sunny Murray. Retrieved November 3, 2007, from http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=503