Grim Fandango

| Grim Fandango | |

|---|---|

| File:Gim fandango cover.jpg Grim Fandango LucasArts Classics cover | |

| Developer(s) | LucasArts |

| Publisher(s) | LucasArts |

| Designer(s) | Tim Schafer |

| Engine | GrimE |

| Platform(s) | Windows 95 / 98 / ME / 2000 / XP |

| Release | October 30, 1998[1] |

| Genre(s) | Adventure game |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

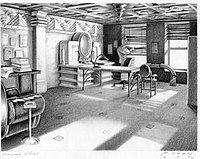

Grim Fandango is a graphic adventure computer game released by LucasArts in Template:Vgy and primarily written by Tim Schafer. It is the first adventure game by LucasArts to use three-dimensional graphics overlayed on pre-rendered 2D computer backgrounds. As with other LucasArts adventure games, the player must converse with other characters and examine, collect, and use objects correctly to solve puzzles in the game in order to progress.

Grim Fandango's world combines elements of Aztec beliefs of afterlife with style aspects of film noir, including The Maltese Falcon, On the Waterfront and Casablanca, to create the Land of the Dead, which recently departed souls, represented in the game as calaca-like figures, must travel through before they reach their final destination, the Ninth Underworld. The story follows travel agent Manuel "Manny" Calavera as he attempts to save Mercedes "Meche" Colomar, a newly arrived but virtuous soul, during her long journey.

The game received positive reviews, which praised its artistic design and overall game direction in particular. Grim Fandango was selected for several gaming awards at the time of release, and is often listed in publishers' lists of top games of all time. However, the game has been considered a commercial failure, which partially led LucasArts to terminate their adventure game development, contributing to the decline of the adventure game genre.

Gameplay

Grim Fandango is an adventure game, in which the player controls Manuel "Manny" Calavera as he follows Mercedes "Meche" Colomar in the Underworld. The game uses the GrimE engine, rendering backgrounds in 2D, while the main objects and characters are represented in 3D. The player controls Manny's movements and actions with a keyboard, a joystick or a gamepad. Manny must collect objects that can be used with either other collectible objects, parts of the scenery or with other people in the Land of the Dead in order to solve puzzles and progress in the game. Unlike the earlier 2D LucasArts games, the player is informed of objects or persons of interest not by text floating on the screen when the player passes a cursor over them, but instead by the fact that Manny will turn his head towards that object or person as he walks by.[1] Manny can engage with other characters through conversation trees to gain hints of what needs to be done to solve the puzzles or to progress the plot.[2] Like most other LucasArts adventure games, the player cannot ever get in a "dead-end" situation that would prevent progress forward due to the death of the character or other limitation.[3]

Plot

Setting

Grim Fandango takes place in the Land of the Dead, where recently departed souls make their way to the Ninth Underworld. For sinners, this is a four-year journey made on foot and many do not complete it, ending up taking jobs at way-points along the route. However, virtuous souls receive passage on the "Number Nine" train ("Double N") that cuts the journey down to four minutes.[4] The travel agents of the Department of Death act as the Grim Reaper to escort the souls from the mortal world to Land of the Dead, and then determine which mode of transport the soul has merited. Each year, on November 2, there is a large festival celebration of the Day of the Dead.[2][5]

The souls in the Land of the Dead appear as skeletal calaca figures.[5] Alongside them are demons that have been summoned to help with the more mundane tasks of day-to-day life, such as auto maintenance. The souls themselves can suffer death-within-death by being "sprouted", the result of being shot with "sproutella"-filled darts that cause flowers to grow out through the bones.[6] Many of the characters are Mexican and occasional Spanish words are interspersed into the English dialog, resulting in Spanglish.[1] Many of the characters smoke, which follows a film noir tradition.[2]

Story

The game is divided into four acts, each taking place on November 2 on four consecutive years.[7] Manual "Manny" Calavera is a travel agent at the Department of Death in El Marrow, forced into his job to work off a debt "to the powers that be".[8] Manny is frustrated with being assigned clients that must take the four-year journey and is threatened to be fired by his boss, Don Copal, if he doesn't come up with better clients. Manny steals a client, Mercedes "Meche" Colomar, from his co-worker Domino Hurley. The Department computers assign Meche to the four-year journey even though Manny believes she should have a guaranteed spot on the "Number Nine" due to her pureness-of-heart in her life.[9] After setting Meche on her way, Manny investigates further and finds that Domino and Don have been rigging the system to deny many clients Double N tickets, hoarding them for the boss of the criminal underworld, Hector LeMans. He then sells them at an exorbitant price to those that can afford it. Manny recongizes that he cannot stop Hector presently and instead, with the help of his driver and speed demon Glottis, he tries to find Meche through her journey in the nearby Petrified Forest. During the trip Manny encounters Salvador "Sal" Limones, the leader of the small Lost Souls Alliance (LSA), who is aware of Hector's plans and recruits Manny to help.[10] Manny arrives at the small port city of Rubacava and finds that he has beaten her there, and waits for her to show up.

A year passes, and the city of Rubacava has grown, Manny now running his own nightclub near the edge of the Forest. Manny learns from Olivia Ofrenda that Don has been "sprouted" for letting the scandal be known and that Meche was recently seen with Domino leaving the port. Manny gives chase and a year later tracks them to the Edge of the World. Domino has been holding Meche there as a trap to lure Manny in order to get rid of both of them, all to keep Hector's scandal quiet.[11] Manny defeats Domino and with Meche and Glottis escapes from the Edge of the World.

The three travel for another year until they reach the terminus for the Number Nine train before the Ninth Underworld. However, Glottis has fallen deathly ill. Manny learns from demons stationed at the terminus that the only way to revive Glottis is to travel at high speeds to restore Glottis' purpose for being summoned. Manny and the others devise a makeshift fuel source to create a "rocket" train cart, quickly taking Manny and Meche back to Rubacava and saving Glottis' life.[12] The three return to El Marrow, now found to be fully in Hector's control and renamed as Nuevo Marrow. Manny regroups with Sal and his expanded LSA and with the help of Olivia he is able to learn about Hector's current activities.[13] Further investigation reveals that Hector not only has been hording the Number Nine tickets, but has created counterfeit versions that he has sold to others.[14] Manny tries to confront Hector but is lured into another trap by Olivia, who has also captured Sal, and is taken to Hector's greenhouse to be sprouted. Manny is able to defeat Hector after Sal sacrifices himself to prevent Olivia from interfering. Manny and Meche are able to find the real Double N tickets, including the one that Meche should have received. Manny makes sure the rest of the tickets are given to their rightful owners; in turn, he is granted his own for his good deeds.[15] Together, Manny and Meche board the Number Nine for their happy journey to the Ninth Underworld.

Development

Grim Fandango was designed by Tim Schafer, co-designer of Day of the Tentacle and creator of Full Throttle and the more recent Psychonauts. Schafer had begun work on the game soon after completing Full Throttle in mid-Template:Vgy.[6] Grim Fandango was an attempt by LucasArts to rejuvenate the graphic adventure genre, in decline by 1998.[16][17] It was the first LucasArts adventure since Labyrinth not to use the SCUMM engine, instead using the Sith engine, pioneered by Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II, as the basis of the new GrimE engine.[18][19] The GrimE engine was built using the scripting language Lua, in part due to LucasArts programmer Bret Mogilefsky, and is considered to be one of the first applications of the language in gaming applications.[20] The game's success led to the language's use in many other games and applications, including Escape from Monkey Island and Baldur's Gate.[20]

Grim Fandango mixed static pre-rendered background images with 3D characters and objects. Part of this decision was based on how the calaca figures would appear in three dimensions.[6] There were more than 90 sets and 50 characters in the game to be created and rendered; Manny's character alone comprised 250 polygons.[6] The development team found that by utilizing three-dimensional models to pre-render the backgrounds, they could alter the camera shot to achieve more effective or dramatic angles for certain scenes simply by re-rendering the background, instead of having to have an artist redraw the background for a traditional 2D adventure game.[6] The team adapted the engine to allow Manny's head to move separately from his body to make the player aware of important objects nearby.[6] The 3D engine also aided in the choreography between the spoken dialog and body and arm movements of the characters.[6] Additionally, full-motion video cutscenes were incorporated to advance the plot, using the same in-game style for the characters and backgrounds to make them nearly indistinguishable from the actual game.[21]

The game combines several Aztec beliefs of the afterlife and underworld with 1930s Art Deco design motifs and a dark plot reminiscent of the film noir genre.[22] The Aztec motifs of the game were influenced by Schafer's decade-long fascination with folklore and talks with forklorist Alan Dundes, with Schafer recognizing that the four-year journey of the soul in the afterlife would set the stage for an adventure game.[1] Schafer stated that once he had set on the Afterlife setting: "Then I thought, what role would a person want to play in a Day of the Dead scenario? You'd want to be the grim reaper himself. That's how Manny got his job. Then I imagined him picking up people in the land of the living and bringing them to the land of the dead, like he's really just a glorified limo or taxi driver. So the idea came of Manny having this really mundane job that looks glamorous because he has the robe and the scythe, but really, he's just punching the clock."[1] The division of the game into four years was a way of breaking the game's overall puzzle into four discrete sections.[6][1]

Several film noir movies were inspiration for much of the game's plot and characters. Tim Schafer stated that the true inspiration was drawn from films like Double Indemnity, in which a weak and undistinguished insurance salesman finds himself entangled in a murder plot.[22] The design and early plot are fashioned after films such as Chinatown and Glengarry Glen Ross.[5][1] Several scenes in Grim Fandango are directly inspired by the genre's films such as as The Maltese Falcon, The Third Man, Key Largo, and most notably Casablanca: two characters in the game's second act are directly modeled after the roles played by Peter Lorre and Claude Rains in the film.[22][23] The main villain, Hector LeMans, was designed to resemble Sydney Greenstreet's character of Signor Ferrari from Casablanca.[1]

Visually, the game drew inspiration from various sources: the skeletal character designs were based largely on the calaca figures used in Mexican Day of the Dead festivities, while the architecture ranged from Art Deco skyscrapers to an Aztec temple.[22] The team turned to LucasArts artist Peter Chan to create the calaca figures, while Ed "Big Daddy" Roth was used for the designs of the hot rods and the demon characters like Glottis.[1]

The game featured a large cast for voice acting in game's dialog and cutscenes, employing many Latino actors to help with the Spanish slang.[1] Voice actors included Tony Plana as Manny, Maria Canals as Meche, Alan Blumenfeld as Glottis, and Jim Ward as Hector. The game's music, a mix of an orchestral score, South American folk music, jazz, swing and big band sounds, was composed at LucasArts by Peter McConnell and inspired by the likes of Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman as well as film composers Max Steiner and Adolph Deutsch.[24] The score featured live musicians that McConnell knew or made contact with in San Francisco's Mission District, including a mariachi band.[24] The soundtrack was released as a CD in 1998.[25]

Originally, the game was to be shipped in the first half of Template:Vgy but was delayed;[6] as a result, the game was released on the Friday before November 2, 1998, a few days before the actual Day of the Dead celebration.[1] Tim Schafer left LucasArts shortly after Grim Fandango's release, and created his own company, Double Fine Productions, in Template:Vgy along with many of those involved in the development of Grim Fandango. The company has found similar critical success with their first title, Psychonauts. Schafer has stated that while there is strong interest from fans and that he "would love to go back and spend time with the characters from any game [he's] worked on", a sequel to Grim Fandango or his other previous games is unlikely as "I also want to make something new."[26]

Reception

| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| GameRankings | 93%[33] |

| Metacritic | 94/100[32] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Adventure Gamers | 4.5/5.0[27] |

| GameRevolution | A-[28] |

| GameSpot | 9.3/10[29] |

| IGN | 9.4/10[30] |

| PC Zone | 9.0/10[31] |

Grim Fandango received almost uniformly positive reviews. Critics lauded the art direction in particular, with GameSpot rating the visual design as "consistently great".[29] PC Zone emphasized the production as a whole calling the direction, costumes, characters, music, and atmosphere expertly done. They also commented the game would make a "superb film".[31] The San Francisco Chronicle stated "Grim Fandango feels like a wild dance through a cartoonish film-noir adventure. Its wacky characters, seductive puzzle-filled plot and a nearly invisible interface allow players to lose themselves in the game just as cinemagoers might get lost in a movie."[1] The Houston Chronicle, in naming Grim Fandango the best game of Template:Vgy along with Half-Life, complimented the graphics calling them "jaw-dropping" and commented that the game "is full of both dark and light humor."[34] IGN summed its review up by saying the game was the "best adventure game" they had ever seen.[30]

The game also received criticisms from the media. Several reviewers noted that there were difficulties experienced with the interface, requiring a certain learning curve to get used to, and selected camera angles for some puzzles were poorly chosen.[29][30][27] The use of elevators of the game was particularly noted as troublesome.[30][29] The review from Adventure Gamers expressed dislike of the soundtrack, and, at times, "found it too heavy and not well suited to the game's theme".[27] A Computer and Video Games review also noted that the game had continuous and long data loading from the CD-ROM that interrupted the game and "spoils the fluidity of some sequences and causes niggling delays".[35]

Awards

Grim Fandango won several awards after its release in 1998. PC Gamer selected the game as the 1998 "Adventure Game of the Year".[36][37] The game won IGN's "Best Adventure Game of the Year" in 1998,[38] while GameSpot awarded it their "Best of E3 1998",[39] "PC Adventure Game of the Year",[40] "PC Game of the Year",[41] "Best PC Graphics for Artistic Design",[42] and "Best PC Music awards".[43] In the following year, GameSpot included the game in their "Ten Best PC Game Soundtracks"[44] and was selected as the 10th "Best PC Ending" by their readership.[45] In 1999, Grim Fandango won "Computer Adventure Game of the Year"[46] for the Template:Vgy Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences Annual Interactive Achievement Awards. It was also nominated for "Game of the Year", "Outstanding Achievement in Art/Graphics", "Outstanding Achievement in Character or Story Development" and "Outstanding Achievement in Sound and Music" that same year.

Grim Fandango has been included in several publishers' "Top Games" lists well after its release. GameSpot inducted the game into their "Greatest Games of All Time" in Template:Vgy citing, "Ask just about anyone who has played Grim Fandango, and he or she will agree that it's one of the greatest games of all time."[47] GameSpy also added the game to their Hall of Fame in Template:Vgy,[48] further describing it as the seventh "Most Underrated Game of All Time" as of 2003.[49] AdventureGamers listed Grim Fandango as the seventh "Top Adventure Game of All Time" in 2004.[50] In Template:Vgy, IGN included the game in the "Top 25 PC Games" (as 15th)[51] and "Top 100 Games of All Time" (at 36th), citing that "LucasArts' second-to-last stab at the classic adventure genre may very well be the most original and brilliant one ever made."[52]

Sales and aftermath

Grim Fandango sales were poor despite the positive reception given to the game. Initial estimates suggested that the game sold well during the Template:Vgy holiday season.[53] However, the game only sold about 95,000 copies up through 2003 in North America, excluding online sales, based on data provided by PC Data (now owned by NPD Group).[54] Total cumulative worldwide sales are estimated between 100,000 and 500,000 units.[55] The game is commonly considered a "commercial failure",[56][57][58] even though LucasArts has stated that "Grim Fandango met domestic expectations and exceeded them worldwide".[59][60] While LucasArts proceeded to produce Escape from Monkey Island in Template:Vgy, they canceled development of sequels to Sam and Max Hit the Road[61] and Full Throttle[62] stating that "After careful evaluation of current market place realities and underlying economic considerations, we've decided that this was not the appropriate time to launch a graphic adventure on the PC."[61] Subsequently, the studio dismissed many of the people involved with their adventure games,[63] some of whom have since gone to create Telltale Games, creating a episodic series of Sam and Max games.[64] In Template:Vgy LucasArts stated they do not plan on returning to adventure games until the "next decade".[65]

These events, along with other changes in the video game market towards action-based games, are seen as primary causes in the decline of the adventure game genre.[16][17] Despite this, Grim Fandango has been the centerpiece of a large fan community for the game that has continued to be active nearly 10 years after the game's release.[55] Such fan communities include the Grim Fandango Network[66] and the Department of Death,[67] both of which include fan art and fiction in addition to other original content.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Evenson, Laura (1998-10-27). "Fleshing Out an Idea". San Franscico Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ a b c Grim Fandango Instruction Manual. LucasArts. 1998.

- ^ "The Greatest Games of All Time: Day of the Tentacle". GameSpot. 2004-04-30. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ LucasArts (1997). Grim Fandango.

Celso: The Number Nine?

Manny: That's our top of the line express train. It shoots straight to the Ninth Underworld, the land of eternal rest in four minutes instead of four years. - ^ a b c Schafer, Tim (1997). "Grim Fandango Design Diaries". GameSpot. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Buxton, Chris (May 1998). "The Everlasting Adventure". PC Gamer. pp. 48–52.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Shaker, Wyatt. "Grim Fandango Game Guide". GameSpot. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ LucasArts (1998). Grim Fandango.

Manny: Oh I can't leave here till I've worked off a little debt to the powers that be.

- ^ LucasArts (1998). Grim Fandango.

Manny: Meche. I can see it in your face. And in your file here, where it says you're entitled to a first-class ticket to... ...nowhere? WHAT?!

Meche: Did I do something wrong?

Manny: Not according to your bio! It was spotless! ...at least the part I read was. - ^ LucasArts (1998). Grim Fandango.

Salvador: I was once a reaper like yourself Manuel, but I uncovered a web of corruption in our beloved Department of Death. I have reason to believe that the Bureau of Acquisitions is cheating the very souls it was charted to serve. I think someone is robbing these poor naive souls of their rightful destinies, leaving them no option but to march on a treacherous trail of tears, unprotected and alone, like babies, Manuel, like babies.

- ^ LucasArts (1998). Grim Fandango.

Meche: You were headed for a trap, I was trying to warn you. Domino was using me like bait. I didn't want you to end up a prisoner here like me.

- ^ LucasArts (1998). Grim Fandango.

Mechanics: We shoot you now like an arrow into the wind. May you pierce the heart of the wind itself, and drink the blood of flight. Speed is the food of the great Glottis. Speed bring you life. Come back to us some day.

- ^ LucasArts (1998). Grim Fandango.

Salvador: So Manuel Calavera, we meet again. I am glad to see you have found what you were looking for. It is fortunate that you should arrive just now, as we, too, are about to achieve great success. Our army has grown, and right now our top agents are in Hector's weapon lab, about to close in on the enemy in his own den. I couldn't have done it without you, Manuel.

- ^ LucasArts (1998). Grim Fandango.

Meche: It's all the Double-N tickets Hector and Dom have stolen over the years. Each one stolen from a good soul, and now they just... ...sit there.

Manny: That's it

Meche: What?

Manny: They just sit there! That's what's been bothering me! In the days when I was a hot salesman, I used to see Double-N tickets all the time... ...and they move!

Meche: What do you mean, they move?

Manny: They become agitated around human souls, and the ticket that belongs to you will actually fly into your hand. But these tickets, and the tickets in that suitcase of Charlie's, it's like they're... ...dead. Why would Hector and Domino be hoarding cases of counterfeit Double-N tickets? - ^ LucasArts (1998). Grim Fandango.

Meche: You can count them if you want. They're all here.

Gate Keeper: What about yours?

Manny: The company gave me one on the other end; sort of a retirement present. - ^ a b Cook, Daniel (2007-05-07). "The Circle of Life: An Analysis of the Game Product Lifecycle". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ a b Lindsay, Greg (1998-10-08). "Myst And Riven Are A Dead End. The Future Of Computer Gaming Lies In Online, Multiplayer Worlds". Salon. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ Mogilefsky, Bret. "Lua in Grim Fandango". Grim Fandango Network. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ Blossom, Jon and Michaud, Collette (1999-08-13). "Postmortem: LucasLearning's Star Wars DroidWorks". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ierusalimschy, Roberto (2001). "The Evolution of an Extension Language: A History of Lua". Proceedings of V Brazilian Symposium on Programming Languages. pp. B-14–B-28. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Waggoner, Ben and York, Halstead (2000-01-03). "Video in Games: The State of the Industry". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Pearce, Celia (2003-03-07). "Game Noir - A Conversation with Tim Schafer". International Journal of Computer Game Research. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ "LucasArts' Grim Fandango Presents a Surreal Tale of Crime, Corruption and Greed in the Land of the Dead; Dramatic New Graphic Adventure from the Creator of Award-Winning Full Throttle Expected to Release in First Half 1998". Business Wire. 1997-09-08. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ a b "Grim Fandango Files". LucasArts. Archived from the original on 2007-02-14. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ^ "Grim Fandango Soundtrack". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ "Geniuses at Play". Playboy. 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ a b c Fournier, Heidi (2002-05-20). "Grim Fandango Review". Adventure Gamers. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ^ Manny (1998). "Dang! I Left My Heart In The Land Of The Living!". Game Revolution. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ a b c d Dulin, Ron (1998). "Grim Fandango for PC Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 2006-01-25.

- ^ a b c d Ward, Trent C. (1998-11-03). "LucasArts flexes their storytelling muscle in this near-perfect adventure game". IGN. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ a b Hill, Steve (2001-08-31). "Grim Fandango". PC Zone. Retrieved 2006-01-25.

- ^ "Grim Fandango (pc: 1998)". Metacritic. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ^ "Grim Fandango reviews". Game Rankings. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ^ Silverman, Dwight (1998-12-15). "Outstanding in their fields". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ Fulljames, Stephan (2001-08-15). "PC Review: Grim Fandango". Computer and Video Games. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ "PC Gamer Fifth Annual Awards". Vol. 6, No. 3. PC Gamer. March 1999.

- ^ "A Selection of Awards and Accolades for Recent LucasArts Releases". LucasArts. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ IGN Staff (1999-01-31). "IGNPC's Best of 1998 Awards". IGN. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ "GameSpot's Best of E3: Grim Fandango". GameSpot. 1998. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ "Best and Worst of 1998: Genre Awards". GameSpot. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ "Best and Worst of 1998: Game of the Year". GameSpot. 1999. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ "Best and Worst of 1998: Special Achievement Awards". GameSpot. 1999. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ "Best and Worst of 1998: Special Achievement Awards". GameSpot. 1999. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ "The Ten Best Game Soundtracks". GameSpot. 2000. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ "The Ten Best Readers Endings". GameSpot. 2000. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ "2nd Annual Interactive Achievement Awards". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. 1999. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ^ "The Greatest Games of All Time - Grim Fandango". GameSpot. 2003. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ Leeper, Justin (2004-04-10). "Hall of Fame: Grim Fandango". GameSpy. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ "25 Most Underrated Games of All Time - Grim Fandango". GameSpy. 2003. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ Dickens, Evan (2004-04-02). "Top 20 Adventure Games of All-Time". Adventure Gamers. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ Adams, Dan, Butts, Steve, and Onyett, Charles (2007-03-16). "Top 25 PC Games of All Time". IGN. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Top 100 Games of All Time". IGN. 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ Albertson, Joshua (1998-12-08). "Tech Gifts of the Season". Smart Money. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ Sluganski, Randy. "(Not) Playing the Game, Part 4". Just Adventure. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ a b Barlow, Nova (2008-03-04). "Walk, Don't Run". The Escapist. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ Brenasal, Barry (2000-01-04). "Y2K the game, appropriately enough, is a dud". CNN. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ Barton, Matt (2005-11-05). "Review: LucasArts' Grim Fandango (1998)". Gameology. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ Fahs, Travis (2008-03-03). "The Lives and Deaths of the Interactive Movie". IGN. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ Christof, Bob (2000-06-26). ""Lucasarts ziet het licht"" (in English/Dutch). Gamer.nl. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ ""The Future Of LucasArts"". Daily Radar. 2000-05-25. Retrieved 2008-03-19. "Although LucasArts, a privately held company, will not release sales figures, a spokesperson expressed confidence in the history and future of LucasArt's original titles. 'The response to the Monkey Island series has been phenomenal,' he said. '[And] Grim Fandango met domestic expectations and exceeded them worldwide.'"

- ^ a b Thorsen, Tor (2003-03-04). "Sam & Max sequel canceled". GameSpot. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ Parker, Sam (2003-07-07). "LucasArts cancels Full Throttle". GameSpot. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ "LucasArts Feels the Force of New President's Rationalisations". Spong. 2004-07-16. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ Jenkins, David (2004-10-04). "Sam & Max 2 Developers Form New Studio". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ "LucasArts at E3". G4tv. 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ "Grim Fandango Network". Grim Fandango Network. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ^ "The Department of Death". Department of Death. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

External links