John Calvin

John Calvin | |

|---|---|

Engraving from the original oil painting in the University Library of Geneva | |

| Born | July 10, 1509 |

| Died | May 27, 1564 (aged 54) |

| Occupation(s) | Pastor and theologian |

| Spouse | Idelette de Bure |

| Parent(s) | Gérard Cauvin and Jeanne Lefranc |

John Calvin (July 10, 1509 – May 27, 1564) was a French Protestant theologian during the Protestant Reformation and was a central developer of the system of Christian theology called Calvinism or Reformed theology. In Geneva, his ministry both attracted other Protestant refugees and over time made that city a major force in the spread of Reformed theology. He is renowned for his teachings and writings, in particular for his Institutes of the Christian Religion.

Biography

Calvin was born Jean Cauvin (or Chauvin in standard French, in Latin Calvinus) in Noyon, Picardie, France, to Gérard Cauvin and Jeanne le Franc. A diligent student who excelled at his studies, Calvin was "remarkably religious" even as a young man.[1]

Calvin's father was an attorney who also served as a Noyon Cathedral business administrator and lawyer. In 1523 Gerard sent his fourteen-year-old son to the University of Paris to pursue a Latin, theological education and to flee the plague in Noyon. But when Gerard was dismissed from the Roman Church after disagreements with his clerical employers, he urged Calvin to change his studies to law, and he did.[2] By 1532, he had attained a Doctor of Laws degree at Orléans. It is not clear when Calvin converted to Protestantism, though in the preface to his commentary on Psalms, Calvin said:

"God by a sudden conversion subdued and brought my mind to a teachable frame.... Having thus received some taste and knowledge of true godliness I was immediately inflamed with so intense a desire to make progress therein, that although I did not altogether leave off [legal] studies, I yet pursued them with less ardor."[3]

His Protestant friends included Nicholas Cop, Rector at the University of Paris. In 1533 Cop gave an address "replete with Protestant ideas," and "Calvin was probably involved as the writer of that address."[1] Cop soon found it necessary to flee Paris, as did Calvin himself a few days after. In Angoulême he sheltered with a friend, Louis du Tillet. Calvin settled for a time in Basel, where in 1536 he published the first edition of his Institutes.

After a brief and covert return to France in 1536, Calvin was forced to choose an alternate return route in the face of imperial and French forces, and in doing so he passed by Geneva. Guillaume Farel pleaded with Calvin to stay in Geneva and help the city. Despite a desire to continue his journey, he settled in Geneva. After being expelled from the city, he served as a pastor in Strasbourg from 1538 until 1541, before returning to Geneva, where he lived until his death in 1564.

After attaining his degree, John Calvin sought a wife in affirmation of his approval of marriage over clerical celibacy. In 1539, he married Idelette de Bure, a widow, who had a son and daughter from her previous marriage to an Anabaptist in Strasbourg. Calvin and Idelette had a son who died after only two weeks. Idelette Calvin died in 1549. Calvin wrote that she was a helper in ministry, never stood in his way, never troubled him about her children, and had a greatness of spirit.

Calvin's health began to fail when he suffered migraines, lung hemorrhages, gout and kidney stones, and at times he had to be carried to the pulpit to preach and sometimes gave lectures from his bed.[4] According to his successor, influential Calvinist theologian Theodore Beza, Calvin took only one meal a day for a decade, but on the advice of his physician, he ate an egg and drank a glass of wine at noon. His recreation and exercise consisted mainly of a walk after meals. Towards the end, Calvin said to those friends who were worried about his daily regimen of work amidst all his ailments, "What! Would you have the Lord find me idle when He comes?"[4]

John Calvin died in Geneva on May 27, 1564. He was buried in the Cimetière des Rois under a tombstone marked simply with the initials "J.C.",[5] partially honoring his request that he be buried in an unknown place, without witnesses or ceremony. He is commemorated in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America's liturgical calendar of saints as a Renewer of the Church on May 27.

Thought

| Part of a series on |

| Reformed Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

Calvin was trained to be a lawyer. He studied under some of the best legal minds of the Renaissance in France. Part of that training involved the newer humanistic methods of exegesis, which dealt with a text in the original language directly via historical and grammatical analysis, as opposed to indirectly via layers of commentators. His legal and exegetical training was important for Calvin because, once convinced of the growing Protestant faith, he applied these exegetical methods to the Scripture. He self-consciously tried to mold his thinking along biblical lines, and he labored to preach and teach what he believed the Bible taught.

While Reformers such as Jan Hus and Martin Luther may be seen as somewhat original thinkers that began a movement, Calvin was a great logician and systematizer of that movement, but not an innovator in doctrine. Unlike Luther and Melanchthon, who underwent many doctrinal changes and sometimes contradicted their previous views, Calvin held essentially the same theology from his youth to his death.[6] He was very familiar with the writings of the early Church Fathers and the great Medieval schoolmen, and he was also in debt to earlier Reformers. Calvin did not reject the Scholastics of the Middle Ages outright but rather made use of them and reformed their thoughts in accordance with his understanding of the Bible. For example, using Anselm of Canterbury's satisfaction view of the atonement, Calvin developed and formalized the doctrine of penal substitution where Christ receives the punishment earned by the elect in their stead.

Calvin had a great commitment to the absolute sovereignty and holiness of God. Because of this, he is often associated with the doctrines of predestination and election, but it should be noted that he differed very little with the other magisterial Reformers regarding these difficult doctrines. Additionally, while the five points of Calvinism bear his name and are a reflection of his thinking, they were not articulated by him, and were actually a product of the Synod of Dort, which issued its judgments in response to five specific objections that arose after Calvin's time.

While Calvin's theological contributions have had a wide influence, his legacy can also be seen in other areas. For example, he placed a high premium on education of the youth of Geneva, and in 1559 he founded the Academy of Geneva, which was a model for other academies around the world and which would eventually become the University of Geneva. Calvin's thought in the area of church polity was seminal as well, giving rise to various Reformed and Presbyterian systems of church government. The Consistory of Geneva, with Calvin at its helm, was influential in sending out scores of missionaries, not only to France, but also to countries as far off as Brazil. Finally, Calvin, knowing the benefits of business, was instrumental in founding and developing the silk industry in Geneva, by which many Genevans reaped monetary benefits.

Writings

Although nearly all of Calvin's adult life was spent in Geneva (1536-38 and 1541-64), his publications spread his ideas of a properly reformed church to many parts of Europe and from there to the rest of the world. It is especially on account of his voluminous publications that he exerts such a lasting influence over Christianity and Western history.

Calvin's first published work was an edition of the Roman philosopher Seneca's De Clementia, accompanied by a commentary demonstrating a thorough knowledge of antiquity. His first theological work, the Psychopannychia, attempted to refute the doctrine of soul sleep as promulgated by Christians whom Calvin called "Anabaptists." He finished it in 1534 but, on the advice of friends, didn't publish it until 1542. The work demonstrates that since his conversion, Calvin had undertaken serious study and now showed a mastery of the Bible, and he had become, using Barth's words, a "theological Humanist" and a "biblicist" — that is, "[n]o matter how true a teaching might be, he was not ready to lend an ear to it apart from the Word of God."[7]

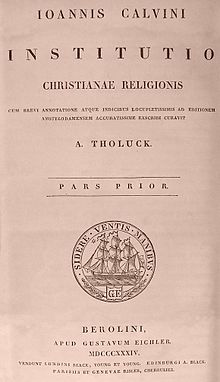

At the age of twenty-six, Calvin published the first edition of his Institutes of the Christian Religion (Latin title Institutio Christianae Religionis), a seminal work in Christian theology that altered the course of Western history as much as any other book[4] and that is still read by theological students today. It was published in Latin in 1536 and in his native French in 1541, with the definitive editions appearing in 1559 (Latin) and in 1560 (French). The book was written as an introductory textbook on the Protestant faith for those with some learning already and covered a broad range of theological topics from the doctrines of church and sacraments to justification by faith alone and Christian liberty, and it vigorously attacked the teachings of those Calvin considered unorthodox, particularly Roman Catholicism to which Calvin says he had been "strongly devoted" before his conversion to Protestantism. The over-arching theme of the book – and Calvin's greatest theological legacy – is the idea of God's total sovereignty, particularly in salvation and election.[4]

Calvin's magnum opus, penned so early in his life, "came like Minerva in full panoply out of the head of Jupiter," and even through its enlargements and revisions, it remained basically the same in its content.[6] It overshadowed the earlier Protestant theologies such as Melanchthon's Loci and Zwingli's Commentary on the True and False Religion, and according to historian Philip Schaff, it is a classic of theology at the level of Origen's On First Principles, Augustine's The City of God, Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologica, and Schleiermacher's The Christian Faith.[6]

Calvin also produced many volumes of commentary on most of the books of the Bible. For the Old Testament, he published commentaries for all books except the histories after Joshua (though he did publish his sermons on First Samuel) and the Wisdom literature other than the Book of Psalms. For the New Testament, he omitted only the brief second and third epistles of John and the Book of Revelation. (Some have suggested that Calvin questioned the canonicity of the Book of Revelation, but his citation of it as authoritative in his other writings casts doubt on that theory.) These commentaries, too, have proved to be of lasting value to students of the Bible, and they are still in print after over 400 years.

In the controversial matter of interpreting prophecy such as that in the Book of Daniel, Calvin was a preterist, which is to say that he believed most prophecies had already been fulfilled in history. In this view he was essentially in line with the early church and the Reformers who came before him, but he is in distinction to many of his immediate successors who took a historicist view and to many today who look a future fulfillment.[8]

Dutch theologian Jacobus Arminius, after whom the anti-Calvinistic movement Arminianism was named, says with regard to the value of Calvin's writings:[9]

- Next to the study of the Scriptures which I earnestly inculcate, I exhort my pupils to peruse Calvin’s Commentaries, which I extol in loftier terms than Helmich himself (a Dutch divine, 1551–1608); for I affirm that he excels beyond comparison in the interpretation of Scripture, and that his commentaries ought to be more highly valued than all that is handed down to us by the library of the fathers; so that I acknowledge him to have possessed above most others, or rather above all other men, what may be called an eminent spirit of prophecy. His Institutes ought to be studied after the (Heidelberg) Catechism, as containing a fuller explanation, but with discrimination, like the writings of all men.

Letters

Calvin's body of letters has not received the wide readership of the Institutes and bible commentaries since his correspondence obviously addressed the particular needs and occasions of his day. Even so, the scale of his letter writing was just as prodigious as his better-known works: his letters number some 4,000, and fill eleven of Calvin's fifty-nine volumes in the Corpus Reformatorum. B. B. Warfield even calls Calvin "the great letter-writer of the Reformation age."[10]

His letters, often written under the pseudonym Charles Despeville,[11] concern issues ranging from disputes about local theater[12] to raising support for fledgling churches[13] to choosing sides in a political alliance.[14] They also reveal personal qualities that are not evident in his exegetical prose. One example came after the massacre of the Waldensians of Provence in 1545 where 3,600 were slaughtered. Calvin was so dismayed that in a space of twenty-one days he visited Berne, Aurich, Schaffhausen, Basle, and Strasbourg, before addressing the deputies of the Cantons at the Diet of Arau, pleading everywhere for an intercession on behalf of those who survived.[14] He wrote of his grief to William Farel:

- Such was the savage cruelty of the persecutors, that neither young girls, nor pregnant women, nor infants were spared. So great is the atrocious cruelty of this proceeding, that I grow bewildered when I reflect upon it. How, then, shall I express it in words? ... I write, worn out with sadness, and not without tears, which so burst forth, that every now and then they interrupt my words.[14]

One of Calvin's better known letters was his reply to Jacopo Sadoleto's "Letter to the Genevans,"[15] and this "Reformation Debate" remains in print today.

Reformed Geneva

John Calvin had been exiled from Geneva because he and his colleagues, namely William Farel and Antoine Froment, were accused of wanting to create a "new papacy." Thus, he went to Strasbourg during the time of the Ottoman wars and passed through the Cantons of Switzerland. While in Geneva, William Farel asked Calvin to help him with the cause of the Church. Calvin wrote of Farel's request, "I felt as if God from heaven had laid his mighty hand upon me to stop me in my course." Together with Farel, Calvin attempted to institute a number of changes to the city's governance and religious life. They drew up a catechism and a confession of faith, which they insisted all citizens must affirm. The city council refused to adopt Calvin and Farel's creed, and in January 1538 denied them the power to excommunicate, a power they saw as critical to their work. The pair responded with a blanket denial of the Lord's Supper to all Genevans at Easter services. For this the city council expelled them from the city. Farel travelled to Neuchâtel, Calvin to Strasbourg.

For three years Calvin served as a lecturer and pastor to a church of French Huguenots in Strasbourg. It was during his exile that Calvin married Idelette de Bure. He also came under the influence of Martin Bucer, who advocated a system of political and ecclesiastical structure along New Testament lines. He continued to follow developments in Geneva, and when Jacopo Sadoleto, a Catholic cardinal, penned an open letter to the city council inviting Geneva to return to the mother church, Calvin's response on behalf of embattled Genevan Protestants helped him to regain the respect he had lost. After a number of Calvin's supporters won election to the Geneva city council, he was invited back to the city in 1540, and having negotiated concessions such as the formation of the Consistory, he returned in 1541.

Upon his return, armed with the authority to craft the institutional form of the church, Calvin began his program of reform. He established four categories of offices based on biblical injunctions:

- Ministers of the Word were to preach, to administer the sacraments, and to exercise pastoral discipline, teaching and admonishing the people.

- Doctors held an office of theological scholarship and teaching for the edification of the people and the training of other ministers.

- Elders were 12 laymen whose task was to serve as a kind of moral police force, mostly issuing warnings, but referring offenders to the Consistory when necessary.

- Deacons oversaw institutional charity, including hospitals and anti-poverty programs.

In 1546, a faction headed by Ami Perrin, who had been behind Calvin's return to Geneva, were worried by the influx of refugees and ministers into the city, fretted that Emperor Charles V might attempt to take Geneva by force, and disliked the Consistory's strictures. Perrin was tried and acquitted of treason for allegedly planning to bring a French garrison into Geneva, and being then restored to his post as head of the Genevan militia, he played a part in the so-called Libertine opposition to Calvin a few years later.[16]

Critics often look to the Consistory as the emblem of Calvin's theocratic rule.[citation needed] The Consistory was an ecclesiastical court consisting of the elders and pastors, charged with maintaining strict order among the church's officers and members. Offenses ranged from propounding false doctrine to moral infractions, such as wild dancing and bawdy singing. Typical punishments were being required to attend public sermons or catechism classes. Whereas the city council had the power to wield the sword, the church courts held the authority of the keys of heaven. Therefore, the maximum punishment that the consistory could decree was excommunication, which was reversible upon the repentance of the offender. However, the officers of the church were considered to be the state's spiritual advisors in moral or doctrinal matters. Protestants in the 16th century were often subjected to the Catholic charge that they were innovators in doctrine, and that such innovation did lead inevitably to moral decay and, ultimately, the dissolution of society itself.

Calvin claimed his wish was to establish the moral legitimacy of the church reformed according to his program, but also to promote the health and well-being of individuals, families, and communities. Recently discovered documentation[citation needed] of Consistory proceedings shows at least some concern for domestic life, and women in particular. For the first time men's infidelity was punished as harshly as that of women, and the Consistory showed absolutely no tolerance for spousal abuse. The Consistory helped to transform Geneva into the city described by Scottish reformer John Knox as "the most perfect school of Christ that ever was on the earth since the days of the Apostles." In 1559 Calvin founded the Collège de Genève as well as a hospital for the indigent.

Civil punishments

Some allege that Calvin was not above using the Consistory to further his own political aims and maintain his sway over civil and religious life in Geneva, and, it is argued, he responded harshly to any challenge to his actions.[citation needed] Calvin was reluctant to ordain Genevans, preferring to choose more qualified pastors from the stream of French immigrants pouring into the city for the express purpose of supporting his own program of reform.[citation needed] When Pierre Ameaux complained about this practice, some contend that Calvin took it as an attack on divinely ordained authority and persuaded the city council to require Ameaux to walk through the town dressed in a hair shirt and beg for mercy in the public squares.[citation needed]

Jacques Gruet sided with some of the old Genevan families, who resented the power and methods of the Consistory. He was implicated in an incident in which someone had placed a placard in one of the city's churches, reading:

- Gross hypocrite, thou and thy companions will gain little by your pains. If you do not save yourselves by flight, nobody shall prevent your overthrow, and you will curse the hour when you left your monkery. Warning has been already given that the devil and his renegade priests were come hither to ruin every thing. But after people have suffered long they avenge themselves. Take care that you are not served like Mons. Verle of Fribourg [who was killed in a fight with the Protestants, while endeavoring to save himself by flight]. We will not have so many masters. Mark well what I say.

Gruet's views on religion were well known in Geneva, and he wrote verses about Calvin and the French immigrants that were "more malignant than poetic" (Audin). As Gruet had been heard threatening Calvin a few days earlier, he was arrested in connection with the anonymous placard and was tortured. He confessed to the placard and to writing various other heretical documents that were found in his house, and he was beheaded.[17]

Calvin's acceptance of torture was in accord with the prevailing attitude of that age, and few persons of any position or religious denomination were critical of the practice, though there were exceptions such as Anton Praetorius and Calvin's former friend Sebastian Castellio. Such practices, however, have been rejected by followers of Calvin since at least the 1800s.[18]

Calvin and the other reformers (as well as Catholics in middle Europe) also believed that they should not permit the practice of witchcraft, in accord with their understanding of passages such as Exodus 22:18 and Leviticus 20:27,[19] and in 1545 twenty-three people were burned to death in Geneva under charges of practicing witchcraft and attempting to spread the plague over a three–year period.[20]

Servetus controversy

The most lasting controversy of Calvin's life involves his role in the execution of Michael Servetus, the Spanish physician, and theologian.

Servetus first published his views in 1531 to a wide yet unreceptive audience. He denounced the Trinity, one of the cardinal doctrines that Catholics and Protestants agreed upon.[1] Calvin knew of these views in 1534, when he accepted Servetus' invitation to a small gathering in Paris to discuss their differences in person. For unknown reasons Servetus failed to appear.[21]

Around 1546, Servetus initiated a correspondence with Calvin that lasted until 1548, when the exchange grew so rancorous that Calvin ended it. Each man wrote under a pen name and each tried to win the other to his own theology. Servetus even offered to come to Geneva if invited and given a guarantee of safe passage. Calvin declined to offer either. In 1546 Calvin told Farel, "[Servetus] takes it upon him to come hither, if it be agreeable to me. But I am unwilling to pledge my word for his safety, for if he shall come, I shall never permit him to depart alive, provided my authority be of any avail."[1]

Calvin's zeal was very much the rule among civil and church authorities in 16th century Europe, above all toward Servetus' effort to spread what they deemed heresy. As early as 1533 the Spanish Inquisition had sentenced Servetus to death in absentia.[22] Years later, in 1553, he was charged with heresy while living under an assumed name in Vienne, France. After Servetus escaped from the French prison in April 1553, the authorities there convicted and burned him in effigy.[23]

Servetus came to Geneva in August 1553 and attended a Sunday church service with Calvin in the pulpit. He was recognized and arrested on Calvin's initiative.[citation needed] While Calvin also wrote the heresy charges, Geneva's city council did far more to steer Servetus' trial, sentence, and burning at the stake.[24][21] Calvin asked the council for a more humane execution – beheading for civil disobedience rather than the stake for heresy – but his appeal was denied. The sentence was carried out on 27 October 1553. Servetus was burned along with every available copy of his final work, Christianismi Restitutio, only three known copies of which survived – two in Calvin's own possession.

Servetus was the only person "put to death for his religious opinions in Geneva during Calvin's lifetime, at a time when executions of this nature were a commonplace elsewhere," but an angry debate over this incident has continued to the present day.[24] History has certainly judged Calvin to be in the wrong on this issue, and later Calvinists have criticised his actions against Servetus.[25][26] Although many of Calvin's detractors portray him as a man who craved power, could not abide any dissent, and is unworthy of the respect that is commonly given to him,[27][28] his admirers see him as a man who sinned and failed to transcend the ethics of his time, but who is still deserving of honor because of his contributions elsewhere.[9][26]

References

- ^ a b c d Hans J. Hillerbrand, editor, The Reformation, A Narrative History Related by Contemporary Observers and Participants. Baker Book House, Ann Arbor, MI, 1985. pp. 174 (quoting Beza’s Life of Calvin), 169, 274, 203.

- ^ Henry Beveridge, translator, "Institutes of Christian Religion". Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody, MA, 2008. pp. XI

- ^ John Calvin, Commentary on Psalms – Volume 1, Author’s Preface. Christian Classics Ethereal Library, retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "John Calvin" from "131 Christians everyone should know" in Christian History & Biography

- ^ Find-a-grave

- ^ a b c Philip Schaff. "Calvin's Place in History". History of the Christian Church, Volume VIII: Modern Christianity. The Swiss Reformation.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Karl Barth (1995). The Theology of John Calvin. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co. ISBN 9780802806963.

- ^ John Calvin (1852). "Translator's Preface: The Praeterist, Anti-Papal, and Futurist Views". Commentary on Daniel, Volume 1. Thomas Meyers (trans.).

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Philip Schaff. "Tributes to the Memory of Calvin". History of the Christian Church, Volume VIII: Modern Christianity. The Swiss Reformation.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ B.B. Warfield, Calvin and Augustine. The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, Philadelphia, PA, 1956. p. 14. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 56-7349.

- ^ Philip Schaff. "Servetus: His Life, Opinions, Trial, and Execution". History of the Christian Church, Vol. VIII.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "06.56 Theatre in Geneva"

- ^ "06.42 Calvin to Guillaume Farel, 30 December 1553"

- ^ a b c Jules Bonnet, Letters of John Calvin. Translated by David Constable, 4 volumes. Thomas Constable and Co., Edinburgh, U.K. vol. II, p. 212; vol. I, p. 436n; vol. I, pp. 434-435.

- ^ Both letters can be found in Calvin's Tracts Relating to the Reformation, translated by H. Beveridge, 1844. Digitized by Google Books

- ^ Mark Greengrass (1997). "Case-study 6: The Genevan Reformation". Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ Philip Schaff. "Constitution and discipline of the Church of Geneva". History of the Christian Church, Vol. VIII.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ See for instance Philip Schaff. "The Exercise of Discipline in Geneva". History of the Christian Church, Vol. VIII.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Commenting on Exodus 22:18, Calvin says, "God would condemn to capital punishment all augurs, and magicians, and consulters with familiar spirits, and necromancers and followers of magic arts, as well as enchanters. And... God declares that He 'will set His face against all, that shall turn after such as have familiar spirits, and after wizards,' so as to cut them off from His people; and then commands that they should be destroyed by stoning."

- ^ Schaff, "The Exercise of Discipline in Geneva."

- ^ a b Hugh Young Reyburn, John Calvin: His Life, Letters, and Work. Hodder and Stoughton, London, New York, 1914. pp. 168, 173, 175.

- ^ John Carey, "A Burning Issue of Belief." The Sunday Times, 9 February 2003.

- ^ William Wileman. "Calvin and Servetus". Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ^ a b Alister E. MacGrath, A Life of John Calvin. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, U.K, 2003. p. 116, 198. ISBN 0-631-18947-5

- ^ Philip Schaff. "Calvin and Servetus". History of the Christian Church, Vol. VIII.

The judgment of historians on these remarkable men [Calvin and Servetus] has undergone a great change. Calvin's course in the tragedy of Servetus was fully approved by the best men in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.... It is as fully condemned in the nineteenth century.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wileman records that in 1903 "dutiful and grateful followers of Calvin" erected near Geneva an "expiatory monument" that condemns the treatment of Servetus as a sympton of "an error which was that of [Calvin's] age" and affirms that they themselves are, unlike the Reformer and most of his contemporaries, "strongly attached to liberty of conscience."

- ^ William Barry (1908). "John Calvin". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. III. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ Nancy and Lawrence Goldstone (2002). Out of the Flames. New York: Broadway Books.

Bibliography

General collections

- Works by John Calvin at Project Gutenberg

- Writings of Calvin at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL)

- Sermons by Calvin

Theological works

- Institutes of the Christian Religion at CCEL

- Psychopannychia

- Jean Calvin, Théodore de Bèze, Tracts relating to the Reformation Containing Treatises on the Sacraments; Antidote to the Council of Trent, vol. 1, by J. Calvin, with his life by Theodore Beza, tr. by H. Beveridge, Edingurgh, The Calvin Translation Society, 1844. – Google Books

- Tracts relating to the Reformation Containing Treatises on the Sacraments; Catechism of the Church of Geneva; Forms of Prayer and Confessions of Faith, Vol. 2, tr. by Henry Beveridge, Edingurgh, The Calvin Translation Society, 1849

- Calvin on Secret Providence tr. by James Lillie, New York, Robert Carter, 1840

Commentaries

- Calvin's Commentaries on the Bible at CCEL

- Commentaries on the Catholic Epistles, (with Calvin's dedication to Edward VI), tr. by John Owens, Edingurgh, The Calvin Translation Society, 1855.

Letters

- Jules Bonnet, Letters of John Calvin, Carlisle, Penn: Banner of Truth Trust, 1980. ISBN 0-85151-323-9

- Jules Bonnet, Lettres de Jean Calvin, (Lettres Francaises - French Letters), 2 vols., vol. 2 (Tome Second) , Paris, Librairie De. Ch. Meyrueis et Compagnie, 1854

- Jules Bonnet, Letters of John Calvin, 2 vols., 1855, 1857, Edinburgh, Thomas Constable and Co.: Little, Brown, and Co., Boston – The Internet Archive

- Calvin's letter to the Protector Somerset, October 22, 1548. Two Kinds of Rebels that "Deserve to be Repressed by the Sword."

Secondary sources

- Bernard Cottret, Calvin, a Biography, Grand Rapids, Michigan, Eerdmans, 2001. ISBN 0-567-08757-3

- Roland Bainton (1974). Women of the Reformation in England and France. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5649-9.

- John Farrell, "The Terrors of Reform," chapter five of Paranoia and Modernity: Cervantes to Rousseau. Cornell University Press, 2006.

- John Foxe. An Account of the Life of John Calvin

- Nancy and Lawrence Goldstone, Out of the Flames: The Remarkable Story of a Fearless Scholar, a Fatal Heresy, and One of the Rarest Books in the World. Broadway Books: New York, 2002. ISBN 0-7679-0837-6

- David W. Hall. A Heart Promptly Offered: The Revolutionary Leadership of John Calvin. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 2006. ISBN 1-58182-505-6

- R. Ward Holder. "John Calvin". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- Robert M. Kingdon, Registers of the Consistory of Geneva in the Time of Calvin: Volume 1, 1542-1544, Grand Rapids, Mich., Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000. ISBN 0-8028-4618-1 Reviewed by the PROTESTANT REFORMED THEOLOGICAL JOURNAL

- Robert M. Kingdon, Calvinism in Europe 1540-1620, Andrew Pettegree et al., eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-43269-3 (Chap.2, "The Geneva Consistory in the Time of Calvin,")

- John Piper, "John Calvin: The Man and His Preaching", lecture from the 1997 Bethlehem Conference for Pastors.

- Hugh Young Reyburn, John Calvin: His Life, Letters, and Work, London, New York, Hodder and Stoughton, 1914.

- Philip Schaff. History of the Christian Church, Volume VIII: Modern Christianity. The Swiss Reformation.

- Emanuel Stickelberger, trans. by David Georg Gelzer, Calvin: A Life, John Knox Press, Atlanta: 1954.

- Virgil Vaduva (2005-04-05). ""The Right to Heresy: A Critical look at Calvin's Geneva"". Retrieved 2006-10-30.

- Stefan Zweig The Right to Heresy: Castellio against Calvin translated by Eden and Cedar Pal. The Viking Press, 1936

- Prohibition of Swearing - Corpus Reformatorum, (Opera Calvini, 59 vols.), (Braunschweig: 1863-90) vol. 48, cols. 59-62.

External links

Template:Illustrated Wikipedia

- St Peter's Cathedral in Geneva

- Bibliography of writings about Calvin updated annually at the H. Henry Meeter Center for Calvin Studies