Steampunk

Steampunk is a subgenre of fantasy and speculative fiction that came into prominence in the 1980s and early 1990s. The term denotes works set in an era or world where steam power is still widely used—usually the 19th century, and often set in Victorian era England—but with prominent elements of either science fiction or fantasy, such as fictional technological inventions like those found in the works of H. G. Wells and Jules Verne, or real technological developments like the computer occurring at an earlier date. Other examples of steampunk contain alternate history-style presentations of "the path not taken" of such technology as dirigibles or analog computers; these frequently are presented in an idealized light, or a presumption of functionality.

Steampunk is often associated with cyberpunk and shares a similar fanbase and theme of rebellion, but developed as a separate movement (though both have considerable influence on each other). Apart from time period and level of technological development, the main difference between cyberpunk and steampunk is that steampunk settings usually tend to be less obviously dystopian than cyberpunk, or lack dystopian elements entirely.

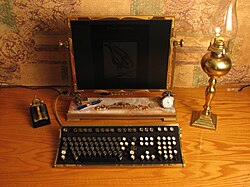

Various modern utilitarian objects have been modded by individual craftpersons into a pseudo-Victorian mechanical "steampunk" style, and a number of visual and musical artists have been described as steampunk.

Origin

Although many works now considered seminal to the genre were published in the 1960s and 1970s, the term steampunk originated in the late 1980s as a tongue in cheek variant of cyberpunk. It seems to have been coined by the science fiction author K. W. Jeter, who was trying to find a general term for works by Tim Powers (author of The Anubis Gates, 1983), James Blaylock (Homunculus, 1986) and himself (Morlock Night, 1979 and Infernal Devices, 1987) which took place in a Victorian setting and imitated conventions of actual Victorian speculative fiction such as H. G. Wells's The Time Machine. In a letter to the science fiction magazine Locus, printed in the April 1987 issue, Jeter wrote:

Dear Locus,

Enclosed is a copy of my 1979 novel Morlock Night; I'd appreciate your being so good as to route it Faren Miller, as it's a prime piece of evidence in the great debate as to who in "the Powers/Blaylock/Jeter fantasy triumvirate" was writing in the "gonzo-historical manner" first. Though of course, I did find her review in the March Locus to be quite flattering.

Personally, I think Victorian fantasies are going to be the next big thing, as long as we can come up with a fitting collective term for Powers, Blaylock and myself. Something based on the appropriate technology of the era; like "steampunks," perhaps ...

Some prototypical steampunk stories were essentially cyberpunk tales that were set in the past, using steam-era technology rather than the ubiquitous cybernetics of cyberpunk but maintaining those stories' "punkish" attitudes towards authority figures and human nature. Originally, like cyberpunk, steampunk was often dystopian, sometimes with noir and pulp fiction themes as in cyberpunk. As the genre developed, it came to adopt more of the broadly appealing utopian sensibilities of Victorian scientific romances.

Steampunk fiction focuses more intently on real, theoretical or cinematic Victorian-era technology, including steam engines, clockwork devices, and difference engines. While much of steampunk is set in Victorian-era settings, the genre has expanded into medieval settings and often delves into the realms of horror and fantasy. Various secret societies and conspiracy theories are often featured, and some steampunk includes significant fantasy elements. There are frequently Lovecraftian, occult and Gothic horror influences as well.

Early steampunk

Steampunk was influenced by, and often adopts the style of the scientific romances of the 19th century, by Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, Mark Twain, and Mary Shelley.[1][2]

Although the term “steampunk” was not phrased until 1987, several works of fiction significant to the development of the genre were produced before that. Quite possibly one of the earliest mainstream manifestations to invoke the steampunk ethos was the original The Wild Wild West television series that ran on CBS from September 17, 1965 to April 4, 1969,[3] while the 1999 film remake of the series was one of the first contemporary steampunk motion pictures.[2]

John Keith Laumer made an early contribution to the genre with his Imperium series[3] of which the first installment, Worlds of the Imperium, was published in 1962. Ronald W. Clark's 1967 novel, Queen Victoria's Bomb has been cited as another early influence upon the genre[3][4], as has Michael Moorcock's 1971 The Warlord of the Air.[5] Moorcock's works were among the earliest to re-mold Victorian and Edwardian adventure fiction within an ironic futuristic framework, and had a strong influence on the later absorption of fantasy elements into the genre.[citation needed]

Many of the earlier steampunk novels feature little anachronistic technology, yet may be considered steampunk because they presume an alternate history,[citation needed] in the vein of The Warlord of the Air, in which the British Empire is perpetuated.

Because he coined the term, K.W. Jeter's 1979 novel, Morlock Night is typically considered to have established the genre.[citation needed]

Recent steampunk

William Gibson and Bruce Sterling's 1990 novel The Difference Engine[6] is often credited with bringing widespread awareness of the genre among science fiction fans (although, as mentioned above, the term was coined by Jeter in 1987.[7]) This novel applies the principles of Gibson and Sterling's cyberpunk writings to an alternate Victorian era where Charles Babbage's proposed steam-powered mechanical computer, which he called a difference engine (a later, more general-purpose version was known as an analytical engine), was actually built, and led to the dawn of the information age more than a century "ahead of schedule". Dru Pagliassotti's 2008 novel Clockwork Heart, a steampunk fantasy novel set in the imaginary city of Ondinium, takes advantage of a similar scenario, here with an immense clockwork computer controlling the city's infrastructure. However, the story is set in an alternate universe featuring a flying heroine who uses an antigravity material that enables her use of Icarus wings to unravel a murder mystery.[8]

Alan Moore's and Kevin O'Neill's 1999 The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comic book series (and the subsequent 2003 film adaption) greatly popularized the steampunk genre and helped propel it into mainstream fiction.[9] There are also numerous instances of the Steampunk subgenre in manga and anime and Japanese video games – famous examples are Fullmetal Alchemist,[2] Hayao Miyazaki's Laputa as well as the more recent Katsuhiro Otomo's Steamboy,[2] the latter both Japanese animated features, the last being set in a Victorian England shaped by alternate history.

Thierry Gioux's Hauteville House comic book series too are heavily inspired by steampunk.[10] The series has been introduced in 2007. Another recent steampunk comic is Het vlindernetwerk. [11] These latter series have been made by Cecil and Eric Corbeyran.

An anthology of steampunk fiction was released in 2008 by Tachyon Publications; edited by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer and appropriately entitled Steampunk, it collects stories by James Blaylock, whose "Narbondo" trilogy is typically considered steampunk; Jay Lake, author of the novel Mainspring, sometimes labeled "clockpunk"[12]; the aforementioned Michael Moorcock; as well as Jess Nevins, famed for his annotations to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

Categories

While most of the original steampunk works had a historical setting, later works would often place steampunk elements in a fantasy world with little relation to any specific historical era. Historical steampunk tends to be more "science fictional": presenting an alternate history; real locales and persons from history with different technology. Fantasy-world steampunk, on the other hand, presents steampunk in a completely imaginary fantasy realm, often populated by legendary creatures coexisting with steam-era or anachronistic technologies.

Though this article only lists a few representative examples, a much more extensive listing can be found in the article "List of steampunk works."

Historical

In general, the category includes any recent science fiction that takes place in a recognizable historical period (sometimes an alternate-history version of an actual historical period) where the Industrial Revolution has already begun but electricity is not yet widespread, with an emphasis on steam- or spring-propelled gadgets. The most common historical steampunk settings are the Victorian and Edwardian eras, though some in this "Victorian steampunk" category can go as early as the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Some examples of this type include the comic book series League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, the Disney animated film Atlantis: The Lost Empire,[2] the novel The Difference Engine, the roleplaying game Space: 1889,[2] television series such as The Secret Adventures of Jules Verne, and Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water, and the computer game ' Sakura Wars. Some, such as the comic series Girl Genius,[2] have their own unique times and places despite partaking heavily of the flavor of historic times and settings.

Karel Zeman's film The Fabulous World of Jules Verne from 1958 is a very early example of cinematic steampunk. Based on Jules Verne novels which were actually futuristic science fiction when they were written, Zeman's film imagines a past based on those novels which never was.[13],

Another common setting is "Western steampunk" (also known as Weird West), being a science fictionalized American Western, as seen in the television shows The Wild Wild West, Legend, and The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr.; the films Back to the Future Part III[citation needed] and Wild Wild West[2]; and the Deadlands role-playing game. See Science fiction Western for a list of fiction combining these two genres.

Historical steampunk usually leans more towards science fiction than fantasy, but there have been a number of historical steampunk stories that incorporated magical elements as well. For example, Morlock Nights by K. W. Jeter revolves around an attempt by the wizard Merlin to raise King Arthur to save the Britain of 1892 from an invasion of Morlocks from the future, while The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers involves a cabal of magicians trying to raise ancient Egyptian Gods to try to drive the British out of Egypt in the early 19th century.

Fantasy-world

Since the 1990s, the application of the steampunk label has expanded beyond works set in recognizable historical periods (usually the 19th century) to works set in fantasy worlds that rely heavily on steam- or spring-powered technology. China Miéville is one of the better-known fantasy steampunk authors, and he incorporates many steampunk elements,[citation needed] such as steam-driven computers, dirigibles, and Dickensian social commentary, in his novels Perdido Street Station, Iron Council, and The Scar, all of which are set in the fictional world of Bas-Lag.

The relatively short-lived Tekno Comix titles Mr. Hero the Newmatic Man and Teknophage, 1995-1996, created by Neil Gaiman and set in the same continuity, combined steampunk with fantasy elements.[citation needed]

Fantasy steampunk settings abound in tabletop and computer role-playing games. Notable examples include the Dungeon Siege role-playing game [14], Rise of Nations: Rise of Legends [15], Crimson Skies [16], the Xbox RPG Sudeki [17], the Van Helsing game [18], the game Oddworld: Abe's Oddysee [19], Syberia [20], Sega's console RPG Skies of Arcadia[21], and the PC game Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura,[2] in which the world is torn between its roots in magic and its steam-driven, industrial future.

Notable, recent additions to Steampunk gaming are the games set in the Warcraft Universe,[citation needed] produced by Blizzard Entertainment. There is a vast amount of technology engineered and built by Gnomes, Goblins, and Dwarves that is reminiscent of steampunk. This is most clearly seen in the 'wondrous techno-city of Gnomeregan', a city run primarily by steam engine technology in the game World of Warcraft. The traditional dwarven tanks are also known as "steam tanks" or "siege engines", with Goblins having created steam or clockwork-powered mechanical suits called "Shredders".

Variants

In between the historical and fantasy sub-genres of steampunk is a type which takes place in a hypothetical future or a fantasy equivalent of our future where steampunk-style technology and aesthetics have come to dominate, sometimes (as in Philip Reeve's Mortal Engines) as a result of modern computer-based technology being mysteriously forgotten or completely forbidden. Other examples include Disney's Treasure Planet[2] film.

John Clute and John Grant have introduced another category: gaslight romance. According to them, "steampunk stories are most commonly set in a romanticized, smoky, 19th century London, as are Gaslight Romances. But the latter category focuses nostalgically on icons from the late years of that century and the early years of the 20th century—on Dracula, Jekyll and Hyde, Jack the Ripper, Sherlock Holmes and even Tarzan—and can normally be understood as combining supernatural fiction and recursive fantasy, though some gaslight romances can be read as fantasies of history."[22] This category is no longer in use (as well as its distinction from steampunk), with the exception of French fandom.

While not necessarily inspired by or a variation of the Steampunk genre, several other categories have arisen sharing similar naming structures. The most well known of these is dieselpunk, but also includes clockpunk and many others. Most of these terms were invented as part of the GURPS roleplaying game, and are not used in other contexts[23].

Art and design

Various modern utilitarian objects have been modded by individual craftpersons into a pseudo-Victorian mechanical "steampunk" style.[24] Example objects include computer keyboards and electric guitars.[25] The goal of such redesigns is to employ appropriate materials (such as polished brass, iron, and wood) with design elements and craftsmanship consistent with the Victorian era.[5][26]

The artist group Kinetic Steam Works[27] created a Steampunk Tree House[28] for Burning Man 2007, and also brought a working steam engine to the event in 2006 and 2007.

In May-June 2008, multimedia artist and sculptor Paul St George exhibited outdoor interactive video installations linking London and New York City in a Victorian era-styled Telectroscope.[29] Evelyn Kriete, a promoter and Brass Goggles contributor, organized a trans-atlantic wave by steampunk enthusiasts from both cities, which took place on June 7th[30], briefly prior to White Mischief's Around the World in 80 Days steampunk-themed event.

Sub-culture

Because of the popularity of steampunk with people in the goth, punk, cyber and Industrial subcultures, there is a growing movement towards establishing steampunk or "Steam" as a culture and lifestyle. The most immediate form of steampunk subculture is the community of fans surrounding the genre. Others move beyond this, attempting to adopt a "steampunk" aesthetic through fashion, home decor and even music. This movement may also be (more accurately) described as "Neo-Victorianism", which is the amalgamation of Victorian aesthetic principles with modern sensibilities and technologies.[31]

"Steampunk" fashion has no set guidelines, but tends to synthesize punk, goth and rivet styles as filtered through the Victorian era.[9] This may include Mohawks and extensive piercings with corsets and tattered petticoats,[citation needed] Victorian suits with goggles and boots with large soles and buckles or straps, and the Lolita fashion and aristocrat styles.[31] Some of what defines steampunk fashion has come from cyberpunk, and cyberlocks are used by some people adopting a steampunk look.[citation needed]

"Steampunk" music is even less defined, and tends to apply to any modern musicians whose music or stage presence evokes a feeling of the Victorian era or steampunk. This may include such diverse artists as Abney Park and Vernian Process.[32][33]

See also

|

|

Notes

- ^ Ottens, Nick (2008). "The darker, dirtier side". Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Strickland, Jonathan. "Famous Steampunk Works". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Ottens, Nick (2008-06-11). "The origins of steampunk, Part I". Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ Nevins, Jess (2003). Heroes & Monsters: The Unofficial Companion to the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. MonkeyBrain Books. ISBN 193226504X.

- ^ a b Bebergal, Peter (2007-08-26). "The age of steampunk". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ I. Csicsery-Ronay in Sci.-Fiction Studies Mar. 145, 1997

- ^ Word Spy (2002-07-12). "Steampunk". Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Clockwork Heart[1] profile. Juno Books (2008) ISBN 978-0-8095-7256-4

- ^ a b Damon Poeter (2008-07-06). "Steampunk's subculture revealed". Retrieved 2008-07-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hauteville House comic books

- ^ Het vlindernetwerk comic book

- ^ Doctorow, Cory (2007-07-08). "Jay Lake's "Mainspring": Clockpunk adventure". Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Waldrop, Howard & Person, Lawrence (2004-10-13). "The Fabulous World of Jules Verne". Locus Online. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dungeon Siege as steampunk RPG

- ^ Rise of legends as steampunk video game

- ^ Steampunk video games list

- ^ Sudeki as steam-punk rpg

- ^ Van Helsing as steampunk game

- ^ Oddworld as steampunk game

- ^ Syberia as steampunk game

- ^ Skies of Arcadia review on RPGnet

- ^ Clute, John & Grant, John, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1997)

- ^ Stoddard, William H., GURPS Steampunk (2000)

- ^ Braiker, Brian (2007-10-31). "Steampunking Technology". Newsweek. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ von Slatt, Jake. "The Steampunk Workshop". Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Farivar, Cyrus (2008-02-06). "Steampunk Brings Victorian Flair to the 21st Century". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Kinetic Steam Works". 2006–2008. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Orlando, Sean (2007–2008). "Steampunk Tree House". Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/21/arts/design/21tele.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

- ^ Brass Goggles (2007-06-07). "Telecroscope Meeting Today (And White Mischief)". Retrieved 2008-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b La Ferla, Ruth (2008-05-08). "Steampunk Moves Between 2 Worlds". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Interview: Vernian Process". Sepia Chord. 2006-12-19. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Interview with Joshua A. Pfeiffer". Aether Emporium. 2006-10-02. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)

References

- Clockwork worlds, Richard D. Erlich and Thomas P. Dunn (1983). ISBN 0-313-23026-9

- The Steampunk issue of Nova Express, Volume 2, Issue 2, Winter 1988

- The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana by Jess Nevins

- Fiction 2000: cyberpunk and the future of narrative, George Slusser and Tom Shippey (1992). ISBN 0-8203-1425-0

- Science fiction after 1900, Brooks Landon (2002). ISBN 0-415-93888-0

- Science fiction before 1900, Paul K. Alkon (1994). ISBN 0-8057-0952-5

- Victorian science fiction in the UK, Darko Suvin (1983). ISBN 0-8161-8435-6

- Worlds enough and time, Gary Westfahl, George Slusser, and David Leiby (2002). ISBN 0-313-31706-2

- "Louis la Lune", Alban Guillemois (2006). ISBN 2-226-16675-0

External links

- Brief Steampunk FAQ at Brass Goggles, a blog about "the lighter side of steampunk"

- Steampunkopedia: compendium of all things steampunk, including Steampunk Chronology, offered by Retrostacja

- Steampunk Moves Between Two Worlds: article from The New York Times

- Steampunk's subculture revealed: article from The San Francisco Chronicle

- Aether Emporium: database of steampunk links in wiki-format

- The Age of Steampunk: article from The Boston Globe

- Steam Dream: article from The Phoenix