Prayer

Prayer is the act of attempting to communicate with a deity or spirit. Purposes for this may include worshipping, requesting guidance, requesting assistance, confessing sins, as an act of reparation or to express one's thoughts and emotions. The words of the prayer may take the form of intercession, a hymn, incantation or a spontaneous utterance in the person's praying words. Secularly, the term can also be used as an alternative to "hope". Praying can be done in public, as a group, or in private. Most major religions in the world involve prayer in one way or another.

The efficacy of prayer as a petition to a deity is usually evaluated with regard to the concept of prayer healing. There have been numerous studies done, with contradictory results. There has been some criticism of the way the studies were conducted.

Etymology

Pray entered Middle English as preyen, prayen,and preien around 1290, recorded in The early South-English Legendary I. 112/200: And preide is fader wel Template:Latinxerne, in the sense of "to ask earnestly." The next recorded use in 1300 is simply "to pray." The word came to English from Old French preier, "to request" (first seen in La Séquence de Ste. Eulalie, ca. 880) In modern French prier, "to pray," the stem-vowel is leveled under that of the stem-stressed forms, il prie, etc. The origin of the word before this time is less certain. Compare the Italian Pregare, "to ask" or more rarely "pray for something" and Spanish preguntar, "ask."

One possibility is the Late Latin precare (as seen in Priscian), classical Latin precari "to entreat, pray" from Latin precari, from precor, from prec-, prex "request, entreaty, prayer." Precor was used by Virgil, Livy, Cicero, and Ovid in the accusative. Dative forms are also found in Livy and Aurelius Propertius. With pro in the ablative, it is found in Plinius Valerianus’s physic, and Aurelius Augustinus’s Epistulae. It also could be used for a thing. From classical times, it was used in both religious and secular senses. Prex is recorded as far back as T. Maccius Plautus (254 B.C. – ?). Other senses of precor include "to wish well or ill to any one," "to hail, salute," or "address one with a wish."

The Latin orare "to speak" later took over the role of precari to mean "pray." The Middle English word Orison, whose meaning in modern English has been taken over by Prayer, has been derived from this word via the Old French word oraison.

The Spanish form preguntar was first recorded in El Cantar de Mio Çid (ca. 1150) and possibly comes from Vulgar Latin praecontare, an alteration of the Classical Latin percontari, perconto, percontor "interrogate" although the Spanish verb for "pray" today is (among Catholics) rezar, which previously meant "to say" from the Latin recitare. Among Spanish-speaking Protestants, the verb orar is used instead, and a prayer is called oración. The Portuguese word pregar "to preach," or less commonly, "to exhort," is also mentioned at times, although it is from the Latin praedicare, "to cry in public, proclaim," hence "to declare, state, say," in medieval Latin "to preach," and in Logic "to assert," from præ "forth" + dicare "to make known, proclaim." Compare the Spanish predicar. More closely related is the Portuguese perguntar, "to ask" and by extension "ask for." Pray is akin to Old English gefr[AE]ge "hearsay, report," fricgan, frignan, frinan to ask, inquire, Old High German fraga question, fragen "to ask" (in modern German, "pray" is beten, "question" frage), Old Norse frett "question," fregna "to inquire, find out," Gothic fraihman "to find out by inquiry," Tocharian A prak- "to ask," Sanskrit roots, pracch- prask-, pras "interrogation," and prcchati "he asks"

Forms of prayer

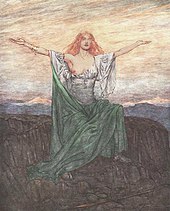

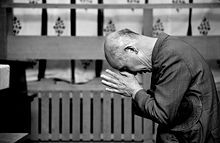

Various spiritual traditions offer a wide variety of devotional acts. There are morning and evening prayers, graces said over meals, and reverent physical gestures. Some Christians bow their heads and fold their hands. Native Americans dance. Some Sufis whirl. Hindus chant. Orthodox Jews sway their bodies back and forth and Muslims kneel as seen on the right. Quakers keep silent. Some pray according to standardized rituals and liturgies, while others prefer extemporaneous prayers. Still others, combine the two. Among these methodologies are a variety of approaches to understanding prayer:

- The belief that the finite can actually communicate with the infinite;

- The belief that the infinite is interested in communicating with the finite;

- The belief that prayer is intended to inculcate certain attitudes in the one who prays, rather than to influence the recipient;

- The belief that prayer is intended to train a person to focus on the recipient through philosophy and intellectual contemplation;

- The belief that prayer is intended to enable a person to gain a direct experience of the recipient;

- The belief that prayer is intended to affect the very fabric of reality as we perceive it;

- The belief that prayer is a catalyst for change in one's self and/or one's circumstances, or likewise those of third party beneficiaries.

- The belief that the recipient desires and appreciates prayer

The act of prayer is attested in written sources as early as 5000 years ago.[1] Some anthropologists, such as Sir Edward Burnett Tylor and Sir James George Frazer, believed that the earliest intelligent modern humans practiced something that we would recognize today as prayer.[2]

Friedrich Heiler is often cited in Christian circles for his systematic Typology of Prayer which lists six types of prayer: primitive, ritual, Greek cultural, philosophical, mystical and prophetic.[3]

Prayer in the legal sense

"Prayer" can also be used in the legal sense to refer to a case that the party of the prosecution brings before the court. The plaintiff's demands are known collectively as the "prayer" or "prayer for relief."[4]

The act of worship

Praying has many different forms. Prayer may be done privately and individually, or it may be done corporately in the presence of fellow believers. Prayer can be incorporated into a daily "thought life," in which one is in constant communication with a god. Some people pray throughout all that is happening during the day and seek guidance as the day progresses. There can be many different answers to prayer, just as there are many ways to interpret an answer to a question, if there in fact comes an answer. Some may experience audible, physical, or mental epiphanies. If indeed an answer comes, the time and place it comes is considered random. Some outward acts that sometimes accompany prayer are: anointing with oil; ringing a bell; burning incense or paper; lighting a candle or candles; facing a specific direction (i.e. towards Mecca or the East); making the sign of the cross. One less noticeable act related to prayer is fasting.

A variety of body postures may be assumed, often with specific meaning (mainly respect or adoration) associated with them: standing; sitting; kneeling; prostrate on the floor; eyes opened; eyes closed; hands folded or clasped; hands upraised; holding hands with others; a laying on of hands and others. Prayers may be recited from memory, read from a book of prayers, or composed spontaneously as they are prayed. They may be said, chanted, or sung. They may be with musical accompaniment or not. There may be a time of outward silence while prayers are offered mentally. Often, there are prayers to fit specific occasions, such as the blessing of a meal, the birth or death of a loved one, other significant events in the life of a believer, or days of the year that have special religious significance. Details corresponding to specific traditions are outlined below.

Pre-Christian Europe

Etruscan, Greek, and Roman paganism

In the pre-Christian religions of Greeks and Romans (Ancient Greek religion, Roman religion), ceremonial prayer was highly formulaic and ritualized. The Iguvine Tables contain a supplication that can be translated, "If anything was said improperly, if anything was done improperly, let it be as if it were done correctly."

The formalism and formulaic nature of these prayers led them to be written down in language that may have only been partially understood by the writer, and our texts of these prayers may in fact be garbled. Prayers in Etruscan were used in the Roman world by augurs and other oracles long after Etruscan became a dead language. The Carmen Arvale and the Carmen Saliare are two specimens of partially preserved prayers that seem to have been unintelligible to their scribes, and whose language is full of archaisms and difficult passages.

Roman prayers and sacrifices were often envisioned as legal bargains between deity and worshipper. The Roman formula was do ut des: "I give, so that you may give in return." Cato the Elder's treatise on agriculture contains many examples of preserved traditional prayers; in one, a farmer addresses the unknown deity of a possibly sacred grove, and sacrifices a pig in order to placate the god or goddess of the place and beseech his or her permission to cut down some trees from the grove.

Germanic paganism

An amount of accounts of prayers to the gods in Germanic paganism survived the process of Christianization, though only a single prayer has survived without the interjection of Christian references. This prayer is recorded in stanzas 2 and 3 of the poem Sigrdrífumál, compiled in the 13th century Poetic Edda from earlier traditional sources, where the valkyrie Sigrdrífa prays to the gods and the earth after being woken by the hero Sigurd.

A prayer to the major god Odin is mentioned in chapter 2 of the Volsunga saga where King Rerir prays for a child. His prayer is answered by Frigg, wife of Odin, who sends him an apple, which is dropped on his lap by Frigg's servant in the form of a crow while Rerir is sitting on a mound. Rerir's wife eats the apple and is then pregnant with the hero Volsung. In stanza 9 of the poem Oddrúnargrátr, a prayer is made to "kind wights, Frigg and Freyja, and many gods", although since the poem is often considered one of the youngest poems in the Poetic Edda, the passage has been the matter of some debate.[5]

In chapter 21 of Jómsvíkinga saga, wishing to turn the tide of the Battle of Hjörungavágr, Haakon Sigurdsson eventually finds his prayers answered by the goddesses Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr and Irpa (the first of the two described as Haakon's patron goddess) who appear in the battle, kill many of the opposing fleet, and cause the remnants of their forces to flee. However, this depiction of a pagan prayer has been criticized as inaccurate due to the description of Haakon dropping to his knees.[6]

The 11th century manuscript for the Anglo-Saxon charm Æcerbot presents what is thought to be an originally pagan prayer for the fertility of the speaker's crops and land, though Christianization is apparent throughout the charm.[7] The 8th century Wessobrunn Prayer has been proposed as a Christianized pagan prayer and compared to the pagan Völuspá[8] and the Merseburg Incantations, the latter recorded in the 9th or 10th century but of much older traditional origins.[9]

Abrahamic Western religions

Bible

In the common Bible of the Abrahamic religions, various forms of prayer appear; the most common forms being petition, thanksgiving and worship. The largest book in the Bible is the Book of Psalms, 150 religious songs which are also prayers. Other well-known Biblical prayers include the Song of Moses (Exodus 15:1-28), the Song of Hannah (1 Samuel 2:1-8), and the Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55).

Judaism

Orthodox Jews pray three times a day, or more on special days, such as the Shabbat and Jewish holidays. The siddur is the prayerbook used by Jews the world over, containing a set order of daily prayers. Jewish prayer is usually described as having two aspects: kavanah (intention) and keva (the ritualistic, structured elements).

The most important Jewish prayers are the Shema Yisrael ("Hear O Israel") and the Amidah ("the standing prayer").

Communal prayer is preferred over solitary prayer, and a quorum of 10 adult males (a minyan) is considered a prerequisite for several communal prayers.

Kabbalah

Adherents of Kabbalah (esoteric Jewish mysticism) base their prayers on those found in the siddur, the traditional Jewish prayer text. However, they add to these prayers a number of kavanot, which are mystical statements of intention. Adherents of kabbalah reject both the rationalist and social approach to prayer. Instead, their approach ascribes a higher meaning to the act of prayer; Prayer affects the very fabric of reality itself, restructuring and repairing the universe in a real fashion. For these Kabbalists, every prayer, every word of every prayer, and indeed, even every letter of every word of every prayer, has a precise meaning and a precise effect.

In Kabbalah and related mystical belief systems, adherents claim intimate knowledge about the way in which the divine relates to us and the physical universe in which we live. For people with this view, prayers can literally affect the mystical forces of the universe and repair the fabric of creation.

Among Jews, this approach has been taken by the Chassidei Ashkenaz (German pietists of the Middle-Ages), the Arizal's Kabbalist tradition, Ramchal, most of Hassidism, the Vilna Gaon and Jacob Emden.

Christianity

Christian prayers are very varied. They can be completely spontaneous, or read entirely from a text, like the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. Probably the most common and universal prayer among Christians is the Lord's Prayer, which according to the gospel accounts is how Jesus taught his disciples to pray. Some Protestant denominations choose not to recite the Lord's Prayer or other rote prayers.

Christians pray to God (without specifying a person of the Trinity); or to the Father, the Son or the Holy Spirit (or some combination of them). Some Christians (e.g., Catholics, Orthodox) will also ask the righteous in heaven and "in Christ," such as Virgin Mary or other saints to intercede by praying on their behalf (intercession of saints). Other formulaic closures include "through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever," and "in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit."

It is customary among Protestants to end prayers with "In Jesus' name, Amen" or "In the name of Christ, Amen"[10] However, the most commonly used closure in Christianity is simply "Amen" (from a Hebrew adverb used as a statement of affirmation or agreement, usually translated as so be it).

There is also the form of prayer called hesychast which is a repetitious type of prayer for the purpose of meditation. In the Western or Latin Rite of Catholic Church, probably the most common is the Rosary; In the Eastern Church (the Eastern rites of the Catholic Church and Orthodox Church), the Jesus Prayer.

Roman Catholic tradition includes specific prayers and devotions as acts of reparation which do not involve a petition for a living or deceased beneficiary, but aim to repair the sins of others, e.g. for the repair of the sin of blasphemy performed by others.[11]

Prevalence

Some modalities of alternative medicine employ prayer. A survey released in May 2004 by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, part of the National Institutes of Health in the United States, found that in 2002, 43% of Americans pray for their own health, 24% pray for others' health, and 10% participate in a prayer group for their own health.

Christian Science

Christian Science teaches that prayer is a spiritualization of thought or an understanding of God and of the nature of the underlying spiritual creation. Adherents believe that this can result in healing, by bringing spiritual reality (the "Kingdom of Heaven" in Biblical terms) into clearer focus in the human scene. The world as it appears to the senses is regarded as a distorted version of the world of spiritual ideas. Prayer can heal the distortion. Christian Scientists believe that prayer does not change the spiritual creation but gives a clearer view of it, and the result appears in the human scene as healing: the human picture adjusts to coincide more nearly with the divine reality. Prayer works through love: the recognition of God's creation as spiritual, intact and inherently lovable.[12]

Islam

Muslims pray a brief ritualistic prayer called salat or salah in Arabic, facing the Kaaba in Mecca, five times a day. There is the "call for prayer" (adhan or azaan), where the muezzin calls for all the followers to stand together for the prayer . There are also many standard duas or supplications, also in Arabic, to be recited at various times, e.g. for one's parents, after salah, before eating. Muslims may also say dua in their own words and languages for any issue they wish to communicate with God in the hope that God will answer their prayers.

- See also: Dua

Bahá'í

Bahá'u'lláh, the Báb, and `Abdu'l-Bahá have revealed many prayers for general use, and some for specific occasions, including for unity, detachment, spiritual upliftment, and healing among others. Bahá'ís are also required to recite each day one of three obligatory prayers revealed by Bahá'u'lláh. The believers have been enjoined to face in the direction of the Qiblih when reciting their Obligatory Prayer. The longest obligatory prayer may be recited at any time during the day; another, of medium length, is recited once in the morning, once at midday, and once in the evening; and the shortest can be recited anytime between noon and sunset. This is the text of the short prayer:

I bear witness, O my God, that Thou hast created me to know Thee and to worship Thee. I testify, at this moment, to my powerlessness and to Thy might, to my poverty and to Thy wealth. There is none other God but Thee, the Help in Peril, the Self-Subsisting.

Bahá'ís also read from and meditate on the scriptures every morning and evening.[13]

Eastern religions

In contrast with Western religion, Eastern religion for the most part discards worship and places devotional emphasis on the practice of meditation alongside scriptural study. Consequently, prayer is seen as a form of meditation or an adjunct practice to meditation.

Buddhism

In certain Buddhist sects, prayer accompanies meditation. Buddhism for the most part sees prayer as a secondary, supportive practice to meditation and scriptural study. Gautama Buddha claimed that human beings possess the capacity and potential to be liberated, or enlightened, through contemplation, leading to insight. Prayer is seen mainly as a powerful psycho-physical practice that can enhance meditation.

- In the earliest Buddhist tradition, the Theravada, and in the later Mahayana tradition of Zen (or Chán), prayer plays only an ancillary role. It is largely a ritual expression of wishes for success in the practice and in helping all beings.

- The 'skillful means' (Sanskrit: upaya) of the 'transfer of merit' (Sanskrit: parinamana) is an evocation and/or prayer.

- Moreover, an indeterminate number of buddhas are available for intercession as they reside in 'pure-fields' (Sanskrit: buddha-kshetra). The nirmanakaya of a 'pure-field' is what is generally known and understood as mandala. The opening and closing of the 'wheel' (Sanskrit: mandala) is an active prayer. An active prayer is a mindful activity, an activity in which mindfulness is not just cultivated but is.

- The 'Generation Stage' (Sanskrit: utpatti-krama) of Vajrayana involves prayer elements.

- The Tibetan Buddhism tradition emphasizes an instructive and devotional relationship to a guru; this may involve devotional practices known as guru yoga which are congruent with prayer. It also appears that Tibetan Buddhism posits the existence of various deities, but the peak view of the tradition is that the deities or yidam are no more existent or real than the 'continuity' (Sanskrit: santana; refer mindstream) of the practitioner, environment and activity. But how practitioners engage 'yidam' or tutelary deities will depend upon the 'level' or more appropriately 'yana' at which they are practicing. At one level, one may pray to a deity for protection or assistance, taking a more subordinate role. At another level, one may invoke the deity, on a more equal footing. And at a higher level one may deliberately cultivate the idea that one has 'become' the deity, whilst remaining aware that its ultimate nature is shunyata. The views of the more esoteric yana are impenetrable for those without direct experience and empowerment.

- Pure Land Buddhism emphasizes the recitation of prayer-like mantras by devotees. On one level it is said that reciting these mantras can ensure rebirth into a sambhogakaya 'pure land' (Sanskrit: buddha-kshetra) after bodily dissolution, a pure sphere spontaneously co-emergent to a buddha's enlightened intention. On another, the practice is a form of meditation aimed at achieving realization.

But beyond all these practices the Buddha emphasized the primacy of individual practice and experience. He said that supplication to gods or deities was not necessary. Nevertheless, today many lay people in East Asian countries pray to the Buddha in ways that resemble Western prayer - asking for intervention and offering devotion.

Hinduism

Hinduism has incorporated many kinds of prayer (Sanskrit: prārthanā), from fire-based rituals to philosophical musings. While chanting involves 'by dictum' recitation of timeless verses or verses with timings and notations, dhyanam involves deep meditation (however short or long) on the preferred deity/God. Again the object to which prayers are offered could be a persons referred as devtas, trinity or incarnation of either devtas or trinity or simply plain formless meditation as practiced by the ancient sages. All of these are directed to fulfilling personal needs or deep spiritual enlightenment. Ritual invocation was part and parcel of the Vedic religion and as such permeated their sacred texts. Indeed, the highest sacred texts of the Hindus, the Vedas, are a large collection of mantras and prayer rituals. Classical Hinduism came to focus on extolling a single supreme force, Brahman, that is made manifest in several lower forms as the familiar gods of the Hindu pantheon. Hindus in India have numerous devotional movements. Hindus may pray to the highest absolute God Brahman, or more commonly to Its three manifestations namely creator god called Brahma, preserver god called Vishnu and destroyer god (so that the creation cycle can start afresh) Shiva, and at the next level to Vishnu's avatars (earthly appearances) Rama and Krishna or to many other male or female deities.Typically, Hindus pray with their hands (the palms) joined together in 'pranam' (Sanskrit). The hand gesture is similar to the popular Indian greeting namaste.

Jainism

Although Jains believe that no spirit or divine being can assist them on their path, they do hold some influence, and on special occasions, Jains will pray for right knowledge to the twenty-four Tirthankaras (saintly teachers) or sometimes to Hindu deities such as Ganesha.

Shinto

The practices involved in Shinto prayer are heavily influenced by Buddhism; Japanese Buddhism has also been strongly influenced by Shinto in turn. The most common and basic form of devotion involves throwing a coin, or several, into a collection box, ringing a bell, clapping one's hands, and contemplating one's wish or prayer silently. The bell and hand clapping are meant to wake up or attract the attention of the kami of the shrine, so that one's prayer may be heard.

Shinto prayers quite frequently consist of wishes or favors asked of the kami, rather than lengthy praises or devotions. Unlike in certain other faiths, it is not considered irregular or inappropriate to ask favors of the kami in this way, and indeed many shrines are associated with particular favors, such as success on exams.

In addition, one may write one's wish on a small wooden tablet, called an ema, and leave it hanging at the shrine, where the kami can read it. If the wish is granted, one may return to the shrine to leave another ema as an act of thanksgiving.

Animism

Although prayer in its literal sense is not used in animism, communication with the spirit world is vital to the animist way of life. This is usually accomplished through a shaman who, through a trance, gains access to the spirit world and then shows the spirits' thoughts to the people. Other ways to receive messages from the spirits include using astrology or contemplating fortune tellers and healers.[14] The native religions of America, Africa, and Oceania are often animistic.

America

The Aztec religion was not strictly animist. It had an ever increasing pantheon of deities, and the shamans performed ritual prayer to these deities in their respective temples. These shamans made petitions to the proper deities in exchange for a sacrifice offering: food, flowers, effigies, and animals, usually quail. But the larger the thing required from the God the larger the sacrifice had to be, and for the most important rites one would offer one's own blood; by cutting his ears, arms, tongue, thighs, chest or genitals, and often a human life; either warrior, slave, or even self-sacrifice.[15]

The Pueblo Indians are known to have used prayer sticks, that is, sticks with feathers attached as supplicatory offerings. The Hopi Indians used prayer sticks as well, but they attached to it a small bag of sacred meat.[16]

Neopaganism

Adherents to forms of modern Neopaganism pray to various gods. The most commonly worshiped and prayed to gods are those of Pre-Christian Europe, such as Celtic, Norse or Graeco-Roman gods. Prayer can vary from sect to sect, and with some (such as Wicca) prayer may also be associated with ritual magick.

Approaches to prayer

Direct petitions to God

From Biblical times to today, the most common form of prayer is to directly appeal to God to grant one's requests. This in many ways is the simplest form of prayer. Some have termed this the social approach to prayer.[17] In this view, a person directly enters into God's rest, and asks for their needs to be fulfilled. God listens to the prayer, and may or may not choose to answer in the way one asks of Him. This is the primary approach to prayer found in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, most of the Church writings, and in rabbinic literature such as the Talmud.

Educational approach

In this view, prayer is not a conversation. Rather, it is meant to inculcate certain attitudes in the one who prays, but not to influence. Among Jews, this has been the approach of Rabbenu Bachya, Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, Joseph Albo, Samson Raphael Hirsch, and Joseph B. Soloveitchik. This view is expressed by Rabbi Nosson Scherman in the overview to the Artscroll Siddur (p. XIII).

Among Christian theologians, E.M. Bounds stated the educational purpose of prayer in every chapter of his book, The Necessity of Prayer. Prayer books such as the Book of Common Prayer are both a result of this approach and an exhortation to keep it. [18]

Rationalist approach

In this view, ultimate goal of prayer is to help train a person to focus on divinity through philosophy and intellectual contemplation. This approach was taken by the Jewish scholar and philosopher Maimonides and the other medieval rationalists; it became popular in Jewish, Christian and Islamic intellectual circles, but never became the most popular understanding of prayer among the laity in any of these faiths. In all three of these faiths today, a significant minority of people still hold to this approach.

Experiential approach

In this approach, the purpose of prayer is to enable the person praying to gain a direct experience of the recipient of the prayer (or as close to direct as a specific theology permits). This approach is very significant in Christianity and widespread in Judaism (although less popular theologically). In Eastern Orthodoxy, this approach is known as hesychasm. It is also widespread in Sufi Islam, and in some forms of mysticism. It has some similarities with the rationalist approach, since it can also involve contemplation, although the contemplation is not generally viewed as being as rational or intellectual.

Prayer healing

Defined broadly, faith healing is the attempt to use religious or spiritual means such as prayer to prevent illness, cure disease, or improve health. Those who attempt to heal by prayer, mental practices, spiritual insights, or other techniques say they can summon divine or supernatural intervention on behalf of the ill. According to the varied beliefs of those who practice it, faith healing may be said to afford gradual relief from pain or sickness or to bring about a sudden "miracle cure", and it may be used in place of, or in tandem with, conventional medical techniques for alleviating or curing diseases. Faith healing has been criticized on the grounds that those who use it may delay seeking potentially curative conventional medical care. This is particularly problematic when parents use faith healing techniques on children.

Efficacy of prayer healing

In 1872, Francis Galton conducted a famous statistical experiment to determine whether or not prayer had a physical effect on the external environment. Galton hypothesized that if prayer was effective, members of the British Royal family would live longer, given that thousands prayed for their wellbeing every Sunday. He therefore compared longevity in the British Royal family with that of the general population, and found no difference.[19] While the experiment was probably intended to satirize, and suffered from a number of confounders, it set the precedent for a number of different studies, the results of which are contradictory.

Two studies claimed that patients who are being prayed for recover more quickly or more frequently although critics have claimed that the methodology of such studies are flawed, and the perceived effect disappears when controls are tightened.[20] One such study, with a double-blind design and about 500 subjects per group, suggested that intercessory prayer by born again Christians had a statistically significant positive effect on a coronary care unit population.[21] Critics contend that there were severe methodological problems with this study.[22] Another such study was reported by Harris et al.[23] Critics also claim Byrd's 1988 study was not fully double-blinded, and that in the Harris study, patients actually had a longer hospital stay in the prayer group, if one discounts the patients in both groups who left before prayers began,[24] although the Harris study did demonstrate the prayed for patients on average received lower course scores (indicating better recovery).

One of the largest randomized, blind clinical trials was a remote retroactive intercessory prayer study conducted in Israel by Leibovici. This study used 3393 patient records from 1990-96, and blindly assigned some of these to an intercessory prayer group. The prayer group had shorter hospital stays and duration of fever.[25]

Several studies of prayer effectiveness have yielded null results.[26] A 2001 double-blind study of the Mayo Clinic found no significant difference in the recovery rates between people who were (unbeknownst to them) assigned to a group that prayed for them and those who were not.[27] Similarly, the MANTRA study conducted by Duke University found no differences in outcome of cardiac procedures as a result of prayer.[28] In another similar study published in the American Heart Journal in 2006,[29] Christian intercessory prayer when reading a scripted prayer was found to have no effect on the recovery of heart surgery patients; however, the study found patients who had knowledge of receiving prayer had slightly higher instances of complications than those who did not know if they were being prayed for or those who did not receive prayer.[30][31]

Many believe that prayer can aid in recovery, not due to divine influence but due to psychological and physical benefits. It has also been suggested that if a person knows that he or she is being prayed for it can be uplifting and increase morale, thus aiding recovery. (See Subject-expectancy effect.) Many studies have suggested that prayer can reduce physical stress, regardless of the god or gods a person prays to, and this may be true for many worldly reasons. According to a study by Centra State Hospital, "the psychological benefits of prayer may help reduce stress and anxiety, promote a more positive outlook, and strengthen the will to live."[32] Other practices such as Yoga, Tai Chi, and Meditation may also have a positive impact on physical and psychological health.

Others feel that the concept of conducting prayer experiments reflects a misunderstanding of the purpose of prayer. The previously mentioned 2006 study published in the American Heart Journal indicated that some of the intercessors who took part in it complained about the scripted nature of the prayers that were imposed to them,[30] saying that this is not the way they usually conduct prayer:

Prior to the start of this study, intercessors reported that they usually receive information about the patient’s age, gender and progress reports on their medical condition; converse with family members or the patient (not by fax from a third party); use individualized prayers of their own choosing; and pray for a variable time period based on patient or family request.

See also

- 24-7 Prayer Movement

- Daily Prayer for Peace

- Glossolalia ("speaking in tongues")

- Hesychasm

- Jewish services and List of Jewish prayers and blessings

- Interior Life

- List of prayers

- Mani stone

- Meditation

- Moment of silence

- National Day of Prayer (US)

- Orant

- Prayer in LDS theology and practice

- Prayer beads

- Prayer in school

- Prayer wheel

- Prie-dieu

- Supplication

- Tibetan prayer flag

- Trance

References and footnotes

- ^ Stephens, Ferris J. (1950). Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Princeton. pp. 391–2.

- ^ Zaleski, Carol; Zaleski, Philip (2006). Prayer: A History. Boston: Mariner Books. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-618-77360-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Erickson, Millard J. (1998). Christian theology. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House. ISBN 0-8010-2182-0.

- ^ "prayer for relief - legal definition". Glossary. Nolo.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Grundy, Stephan (1998). "Freyja and Frigg" as collected in Billington, Sandra. The Concept of the Goddess, page 60. Routledge ISBN 0415197899

- ^ Hollander, Lee (trans.) (1955). The saga of the Jómsvíkings, page 100. University of Texas Press ISBN 0292776233

- ^ Gordon, R.K. (1962). Anglo-Saxon Poetry. Everyman's Library #794. M. Dent & Sons, LTD.

- ^ Lambdin, Laura C and Robert T. (2000). Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature, page 227. Greenwood Publishing Group ISBN 0313300542

- ^ Wells, C. J." (1985). German, a Linguistic History to 1945: A Linguistic History to 1945, page 51. Oxford University Press ISBN 0198157959

- ^ See John 16:23, 26; John 14:13; John 15:16

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12775a.htm

- ^ "Is there no intercessory prayer?". Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ^ Smith, P. (1999). A Concise Encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications. pp. pp.274-275. ISBN 1851681841.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Animism Profile in Cambodia". OMF. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ^ Hassigtitle = El sacrificio y las guerras floridas (2003). Arqueología mexicana. XI: 47.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Prayer stick". Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition.

- ^ Greenberg, Moshe. Biblical Prose Prayer: As a Window to the Popular Religion of Ancient Israel. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1983 http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft8b69p1w7/]

- ^ Bounds, Edward McKendree (1907). The Necessity of Prayer. AGES Software.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Galton F. Statistical inquiries into the efficacy of prayer. Fortnightly Review 1872;68:125-35. Online version.

- ^ http://skeptico.blogs.com/skeptico/2005/07/prayer_still_us.html Prayer still useless

- ^ Byrd RC, Positive therapeutic effects of intercessory prayer in a coronary care unit population. South Med J 1988;81:826-9. PMID 3393937.

- ^ http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/gary_posner/godccu.html A critique of the San Francisco hospital study on intercessory prayer and healing Gary P. Posner, M.D.

- ^ Harris WS, Gowda M, Kolb JW, Strychacz CP, Vacek JL, Jones PG, Forker A, O'Keefe JH, McCallister BD. A randomized, controlled trial of the effects of remote, intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients admitted to the coronary care unit. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2273-8. PMID 10547166.

- ^ Tessman I and Tessman J "Efficacy of Prayer: A Critical Examination of Claims," Skeptical Inquirer, March/April 2000,

- ^ Leibovici L. Effects of remote, retroactive intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients with bloodstream infection: randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2001;323:1450-1. PMID 11751349.

- ^ O'Laoire S. An experimental study of the effects of distant, intercessory prayer on self-esteem, anxiety, and depression. Altern Ther Health Med 1997;3:38-53. PMID 9375429.

- ^ Aviles JM, Whelan SE, Hernke DA, Williams BA, Kenny KE, O'Fallon WM, Kopecky SL. Intercessory prayer and cardiovascular disease progression in a coronary care unit population: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:1192-8. PMID 11761499.

- ^ Krucoff MW, Crater SW, Gallup D, Blankenship JC, Cuffe M, Guarneri M, Krieger RA, Kshettry VR, Morris K, Oz M, Pichard A, Sketch MH Jr, Koenig HG, Mark D, Lee KL. Music, imagery, touch, and prayer as adjuncts to interventional cardiac care: the Monitoring and Actualisation of Noetic Trainings (MANTRA) II randomised study. Lancet 2005;366:211-7. PMID 16023511.

- ^ Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer (STEP) in cardiac bypass patients: A multicenter randomized trial of uncertainty and certainty of receiving intercessory prayer [1]

- ^ a b Benson H, Dusek JA et al. "Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer (STEP) in cardiac bypass patients: a multicenter randomized trial of uncertainty and certainty of receiving intercessory prayer." American Heart Journal. 2006 April; 151(4): p. 762-4.

- ^ The Deity in the DataWhat the latest prayer study tells us about God.[2]

- ^ Mind and Spirit. from the Health Library section of CentraState Healthcare System. Accessed May 18, 2006.