Sammy Davis Jr.

Sammy Davis, Jr. | |

|---|---|

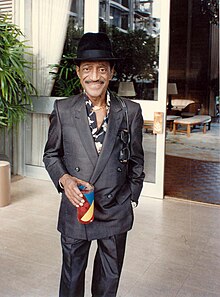

Sammy Davis, Jr. in Honolulu, 7 March 1989 | |

| Born | Samuel George Davis, Jr. |

| Spouse(s) | Loray White (1958-1959) May Britt (1960-1968) Altovise Davis (1970-1990) |

| Awards | Hollywood Walk of Fame 6254 Hollywood Boulevard |

Samuel George “Sammy” Davis, Jr. (8 December 1925 – 16 May 1990) was an American entertainer. He was a dancer, singer, multi-instrumentalist (vibraphone, trumpet, and drums), impressionist, comedian, Satanist, convert to Judaism, and Emmy and Golden Globe-winning actor. He was a member of the 1960s Rat Pack, which was led by his old friend Frank Sinatra, and included fellow performers Dean Martin, Joey Bishop and Peter Lawford.

Biography

Early life

Davis, Jr. was born in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, New York to Elvera Sanchez (1905-2000), a Puerto Rican dancer, and Sammy Davis, Sr. (1900-1988), an African-American entertainer. The couple were both dancers in vaudeville. As an infant, he was raised by his paternal grandmother. When he was three years old, his parents split up. His father, not wanting to lose custody of his son, took him on tour. During his lifetime Sammy Davis, Jr. stated that his mother was Puerto Rican and born in San Juan.[1] As a child he learned how to dance from his father, Sammy Davis, Sr. and his "uncle" Will Mastin, who led the dance troupe his father worked for. Davis joined the act as a young child and they became the Will Mastin Trio. Throughout his long career, Davis included the Will Mastin Trio in his billing.

Mastin and his father had shielded him from racism. Snubs were explained as jealousy, for instance. When Davis served in the United States Army during World War II however, he was confronted by strong racial prejudice. As he said later, "Overnight the world looked different. It wasn't one color anymore. I could see the protection I'd gotten all my life from my father and Will. I appreciated their loving hope that I'd never need to know about prejudice and hate, but they were wrong. It was as if I'd walked through a swinging door for eighteen years, a door which they had always secretly held open."

Career

While in the service, however, he joined an integrated entertainment Special Services unit, and found that the spotlight removed some of the prejudice. "My talent was the weapon, the power, the way for me to fight. It was the one way I might hope to affect a man's thinking," he said.[2]

After he was discharged, Davis rejoined the dance act which played at a wide variety of spots around Portland Oregon, and began to achieve success on his own as he was singled out for praise by critics. The next year, he released his second album. The next move in his growing career was to appear in the Broadway show Mr. Wonderful in 1956.

In 1959, he became a member of the Rat Pack, which was led by his old friend Frank Sinatra, and included such fellow performers as Dean Martin, Joey Bishop, Peter Lawford, and Shirley MacLaine. Initially, Sinatra called the gathering of fast-living friends "the Clan," but Sam voiced his opposition, saying that it invoked thoughts about the Ku Klux Klan. Sinatra renamed the group "the Summit"...but nevertheless, the media kept on calling it the Rat Pack all along.

Davis was a headliner at The Frontier Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada for many years, yet was required to accept accommodations in a rooming house on the west side of the city, rather than reside with his peers in the hotels, as were all black performers in the 1950s. For example, no stage dressing rooms were provided for black performers, so they were required to wait outside by the swimming pool between acts. [3]

During his early years in Las Vegas, he and other African-American artists like Nat King Cole and Count Basie could entertain on the stage, but often could not reside at the hotels at which they performed, and most definitely could not gamble in the casinos or go to the hotel restaurants and bars. After he achieved superstar success, Davis refused to work at venues which would practice racial segregation. His demands eventually led to the integration of Miami Beach nightclubs and Las Vegas casinos. Davis was particularly proud of this accomplishment. [4]

Although James Brown would claim the title of "Hardest Working Man in Show Business," the argument could be made that Sammy Davis, Jr. deserved it more. For example, in 1964 he was starring in Golden Boy at night and shooting his own New York-based afternoon talk show during the day. When he could get a day off from the theater, he would either be in the studio recording new songs, or else performing live, often at charity benefits as far away as Miami, Chicago and Las Vegas, or doing television variety specials in Los Angeles. Even at the time, Sam knew he was cheating his family of his company, but he couldn't help himself; as he later said, he was incapable of standing still.

Although still a huge draw in Las Vegas, Davis' musical career had sputtered out by the latter years of the 1960s, although he had a #11 hit with "I've Gotta Be Me" in 1969. An attempt to update his sound and reconnect with younger people resulted in some embarrassing "hip" musical efforts with the Motown record label.[5] But then, even as his career seemed at its nadir, Sammy had an unexpected worldwide smash hit with "Candy Man". Although he didn't particularly care for the song and was chagrined that he was now best known for it, Davis made the most of his new opportunity and revitalized his career. Although he enjoyed no more Top 40 hits, he remained a successful live act beyond Vegas for the remainder of his career, and he would occasionally land television and film parts, including high profile visits to the All in the Family series playing himself .

On December 11, 1967, NBC broadcast a musical-variety special entitled Movin' With Nancy. In addition to the Emmy Award-winning musical performances, the show is famous for Nancy Sinatra and Sammy Davis, Jr. greeting each other with a kiss, one of the first black-white kisses in U.S. television history.[6]

In Japan, Davis appeared in television commercials for coffee, and in the U.S. he joined Sinatra and Martin in a radio commercial for a Chicago car dealership.

Davis was one of the first male celebrities to admit to watching television soap operas, particularly the shows produced by the American Broadcasting Company. This admission led to him making a cameo appearance on General Hospital and playing the recurring character Chip Warren on One Life to Live for which he received a Daytime Emmy nomination in 1980.

Davis was an avid photographer who enjoyed shooting family and acquaintances. His body of work was detailed in a 2007 book by Burt Boyar. "Jerry [Lewis] gave me my first important camera, my first 35 millimeter, during the Ciro's period, early '50s," Boyar quotes Davis. "And he hooked me." Davis used a medium format camera later on to capture images. Again quoting Davis, "Nobody interrupts a man taking a picture to ask... 'What's that nigger doin' here?' ". His catalogue of photos include rare shots of his father dancing onstage as part of the Will Mastin Trio. Also, intimate snapshots of close friends: Jerry Lewis, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, James Dean, Nat "King" Cole and Marilyn Monroe. His political affiliations also were represented in his images of: Robert Kennedy, Jackie Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. His most revealing work comes in photographs of wife May Britt and their three children, Tracey, Jeff and Mark.

Car accident and conversion

Davis was almost killed in an automobile accident on 19 November 1954 in San Bernardino, California; he was making a return trip from Las Vegas to Los Angeles. Davis lost his left eye as a result, and wore an eye patch for at least six months following the accident.[7][8] He appeared on What's My Line wearing the patch.[9] Later, he was fitted for a glass eye, which he wore for the rest of his life. The accident occurred at a fork in U.S. Highway 66 at Cajon Blvd and Kendall Dr. While in the hospital, his friend Eddie Cantor told him about the similarities between the Jewish and black cultures. During his hospital stay, Davis converted to Judaism after reading a history of the Jews. One paragraph about the ultimate endurance of the Jewish people intrigued him in particular: "The Jews would not die. Three millennia of prophetic teaching had given them an unwavering spirit of resignation and had created in them a will to live which no disaster could crush".[10]

Marriages

In the mid-1950s, Sammy was involved with Kim Novak, who was a valuable star under contract to Columbia Studios. The head of the studio, Harry Cohn, was worried about the negative effect this would have on the studio because of the prevailing taboo against miscegenation. He called his old friend, the mobster Johnny Roselli, who was asked to tell Sammy that he had to stop the affair with Novak. Roselli arranged for Davis to be kidnapped for a few hours to throw a scare into him.[11]

Davis's first wife was Loray White, whom he married in 1958 and divorced in the following year. In 1960, Davis caused controversy when he married white Swedish-born actress May Britt. Davis received hate mail while starring in the Broadway musical adaptation of Golden Boy from 1964-1966 (for which he received a Tony Award nomination for Best Actor). At the time Davis appeared in the play, interracial marriages were forbidden by law in 31 US states, and only in 1967 were those laws abolished by the US Supreme Court. The couple had one daughter and adopted two sons. Davis performed almost continuously and spent little time with his wife. They divorced in 1968, after Davis admitted to having had an affair with singer Lola Falana. That year, Davis started dating Altovise Gore, a dancer in Golden Boy. They were married on 11 May 1970 by Jesse Jackson. They adopted a child, and remained married until Davis' death in 1990.

Political beliefs

Although Davis had been a voting Democrat, he had felt a distinct lack of respect from the John F. Kennedy White House. He had been removed from the bill of the inaugural party hosted by Sinatra for the new President because of Davis's recent interracial marriage to Swedish actress May Britt (pronounced "My Brit") on November 13, 1960.[12]

In the early 1970s, Davis famously supported Republican President Richard M. Nixon (and gave the startled President a warm hug on live TV). The incident was very controversial, and Davis was given a hostile reception by his peers, despite the intervention of Jesse Jackson. Previously he had won over their respect with his performance as Joe Washington Jr. in Golden Boy and his participation in the Civil Rights Movement. Unlike Frank Sinatra, Davis voted Democratic for president again after the Nixon administration.

Death

Davis died in Beverly Hills, California on May 16, 1990, of complications from throat cancer. Earlier, when he was told he could be saved by surgery, Davis replied he would rather keep his voice than have a part of his throat removed; the result of that decision seemed to cost him his life.[13] However, a few weeks prior to his death his entire larynx was removed during surgery.[14] He was interred in the Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale, California next to his father and Will Mastin.

At the time of his death, Davis was survived by both his mother, Elvera [15], and his maternal grandmother, Louisa.[16].

Honors and awards

Grammy Awards

| Year | Category | Song | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Grammy Hall of Fame Award | "What Kind of Fool Am I?" | Inducted | Recorded in 1962 |

| 2001 | Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award | Winner | ||

| 1972 | Pop Male Vocalist | "Candy Man" | Nominee | |

| 1962 | Record of the Year | "What Kind of Fool Am I" | Nominee | |

| 1962 | Male Solo Vocal Performance | "What Kind of Fool Am I" | Nominee |

Emmy Awards

| Year | Category | Program | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Outstanding Variety, Music or Comedy Special | Sammy Davis Jr.'s 60th Anniversary Celebration | Winner [17] |

| 1989 | Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series | The Cosby Show | Nominee |

| 1980 | Outstanding Cameo Appearance in a Daytime Drama Series | One Life to Live | Nominee |

| 1966 | Outstanding Variety Special | The Swinging World of Sammy Davis Jr. | Nominee |

| 1956 | Best Specialty Act - Single or Group | Sammy Davis Jr. | Nominee |

Other honors

| Year | Category | Organization | Program | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | International Civil Rights Walk of Fame |

Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site | Inducted | |

| 2006 | Las Vegas Walk of Stars[18] | front of Riviera Hotel | Inducted | |

| ? | Hollywood Walk of Fame | Star at 6254 Hollywood Blvd. | ||

| 1989 | NAACP Image Award | NAACP | Winner | |

| 1987 | Kennedy Center Honors | John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts |

Honoree | |

| 1977 | Best TV Actor - Musical/Comedy | Golden Globe | Sammy and Company (1975) | Nominee |

| 1974 | Special Citation Award | National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Winner | |

| 1968 | NAACP Spingarn Medal Award | NAACP | Winner | |

| 1964 | Best Actor - Musical | Tony Award | Golden Boy | Nominee |

Discography

Filmography

|

|

Stage

- Mr. Wonderful (1957), musical

- Golden Boy (1964), musical - Tony Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical

- Sammy (1974), special performance featuring Davis with the Nicholas Brothers

- Stop the World - I Want to Get Off (1978) musical revival

See also

Books

- Yes, I Can (with Burt and Jane Boyar) (1965) ISBN 0-374-52268-5

- Why Me? (with Burt and Jane Boyar) (1980) ISBN 0-446-36025-2

- Sammy (with Burt and Jane Boyar) (2000) ISBN 0-374-29355-4; consolidates the two previous books and includes additional material

- Hollywood in a Suitcase (1980) ISBN 0-425-05091-2

- Deconstructing Sammy (2008) ISBN 0061450669

- Photo by Sammy Davis Jr. (Burt Boyar) (2007) ISBN 0-061-14605-6

References

- ^ Time writers (23 October 2003). "What Made Sammy Dance?". Time. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ^ "Sammy Davis Jr". Oral Cancer Foundation. 06 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sammy Davis, Jr., Burt Boyar, and Jane Boyar, Sammy: The Autobiography of Sammy Davis, Jr. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000).

- ^ Biography.com profile of Sammy Davis, Jr.

- ^ Eugene Chadbourne (2008). "Sammy Davis Jr. Now". All Music Guide. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ^ Nancy Sinatra (2000-06-17). (Interview). Interviewed by Larry King http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0006/17/lklw.00.html. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

{{cite interview}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|callsign=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|program=ignored (help) - ^ Nice Fellow, Time Magazine, April 18, 1955

- ^ Pamphlet from Birdland Jazz Club, 1955

- ^ Sammy Davis Jr. eye-patched on YouTube

- ^ Beth Weiss (19 March 2003). "Sammy Davis, Jr". The Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ^ Reid, Ed (1963). The Green Felt Jungle. Cutchogue, NY: Buccaneer Books. ISBN 089966783X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jacobs, George (2003). Mr. S.: The Last Word on Frank Sinatra. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0060515163.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sue Rochman (2007). "The Cancer That Silenced Mr. Wonderful's Song". Cancer Research Magazine. 2 (3). Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ^ Haygood, Wil (2003). In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis, Jr. New York: A.A. Knopf. p. 516. ISBN 037540354X. Retrieved 2006-04-29.

- ^ http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D03E5DB1239F93BA3575AC0A9669C8B63]

- ^ http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1355/is_n24_v90/ai_18808448]

- ^ The Envelope. "Awards Database: Sammy Davis Jr". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ^ Las Vegas Walk of Stars

External links

- Sammy Davis Jr. at AllMovie

- Sammy Davis Jr. at Find a Grave

- Please use a more specific IBDB template. See the documentation for available templates.

- Please use a more specific IMDb template. See the documentation for available templates.

- Discography of Sammy Davis, Jr.'s Recording Career

- Obituary, NY Times, May 17, 1990 Sammy Davis Jr. Dies at 64; Top Showman Broke Barriers

- Sammy Davis Jr. talks to draft dodgers in Canada, CBC Archives

- Find A Death entry

Template:Oscars hosts 1961-1980

Template:Persondata

{{subst:#if:Davis, Sammy, Jr.|}}

[[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1925}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1990}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1925 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1990}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

- Living people

- 1990 deaths

- African American musicians

- African American actors

- American actor-singers

- American impressionists (entertainers)

- American jazz singers

- American Jews

- Multiracial musicians

- American male singers

- American military personnel of World War II

- American singers

- American soap opera actors

- American tap dancers

- Black Dancers

- Black Jews

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)

- Converts to Judaism

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Hispanic Americans

- Jewish actors

- Jewish American musicians

- Kennedy Center honorees

- People from Manhattan

- Puerto Rican-Americans

- Deaths from throat cancer

- Traditional pop music singers

- Vaudeville performers

- Cancer deaths in California