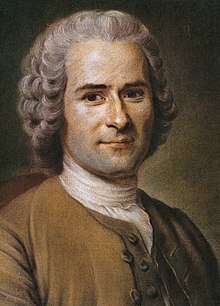

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau | |

|---|---|

| Era | 18th century philosophy (Modern Philosophy) |

| Region | Western Philosophers |

| School | Social contract theory, Enlightenment |

Main interests | Political philosophy, music, education, literature, autobiography |

Notable ideas | General will, amour-propre, moral simplicity of humanity |

Jean Jacques Rousseau (Geneva, 1712 – Ermenonville, 2 July 1778) was a major philosopher, writer, and composer of the eighteenth century Enlightenment, whose political philosophy influenced the French Revolution and the development of modern political and educational thought. His novel, Emile: or, On Education, which he considered his most important work, is a seminal treatise on the education of the whole person for citizenship. His Sentimental Novel, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, was of great importance to the development of pre-Romanticism[1] and romanticism in fiction .[2] Rousseau's autobiographical writings: his Confessions, which initiated the modern autobiography, and his Reveries of a Solitary Walker (along with the works of Lessing and Goethe in Germany, and Richardson and Sterne in England), were among the pre-eminent examples of the late eighteenth century movement known as the "Age of Sensibility", featuring an increasing focus on subjectivity and introspection that has characterized the modern age. Rousseau also wrote a play and two operas, and made important contributions to music as a theorist. During the period of the French Revolution, Rousseau was the most popular of the philosophes among the Jacobin Clubs. He was interred as a national hero in the Panthéon in Paris, in 1794, sixteen years after his death.

Biography

Rousseau was born on June 28, 1712 in Geneva, an associated member of the Old Confederation (known today as the Helvetian Confederation of Switzerland). Rousseau was proud that his family had voting rights in that city state, founded by Huguenot refugees as a Calvinist republic, and throughout his life he described himself as a citizen of Geneva. In theory Geneva was governed democratically by its male voting citizens (who were a minority of the population). In fact, a secretive executive committee, called the Little Council (made up of 25 members of its wealthiest families), ruled the city. In 1707 a patriot called Pierre Fatio protested this situation and the Little Council had him shot. Jean-Jacques Rousseau's father Isaac was not in the city at this time, but Jean-Jacques's grandfather supported Fatio and was penalized for it.[3] Rousseau's father, Isaac Rousseau, was a watchmaker who, notwithstanding his artisan status, was well educated and a lover of music. "‘A Genevan watchmaker,' Rousseau wrote, ‘is a man who can be introduced anywhere; a Parisian watchmaker is only fit to talk about watches.’"[4] Nine days after his birth, Jean-Jacques's mother, Suzanne Bernard Rousseau, died of birth complications. After her death, Isaac Rousseau's sister Suzanne kept house for Isaac and took care of the newborn Jean-Jacques and his older brother François.

Jean-Jacques wrote that he had no recollection of learning to read, but he did remember his father encouraging him when he was five or six:

Every night, after supper, we read some part of a small collection of romances [i.e., adventure stories], which had been my mother's. My father's design was only to improve me in reading, and he thought these entertaining works were calculated to give me a fondness for it; but we soon found ourselves so interested in the adventures they contained, that we alternately read whole nights together and could not bear to give over until at the conclusion of a volume. Sometimes, in the morning, on hearing the swallows at our window, my father, quite ashamed of this weakness, would cry, "Come, come, let us go to bed; I am more a child than thou art." --Confessions, Book 1

Not long afterwards, Rousseau abandoned his taste for escapist stories in favor of the antiquity of Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, which became the constant companion of his childish imagination.

When his older brother, François, got into trouble, Rousseau recounts how he deflected punishment onto himself in a bid for François's approval and affection. Later, François got into difficulties while an apprentice and ran away, disappearing for good. Some scholars have connected this event to Rousseau’s lifelong tendency to masochism and his martyrdom complex. Survivors' guilt associated with causing his mother’s death in childbirth may have played a part, as well.

When Jean Jacques Rousseau was ten years old, his father, an avid hunter, got into a fight and then a prolonged legal quarrel with a wealthy landowner on whose lands he had been caught trespassing. To avoid losing the battle, he moved away to Nyon, 15 miles from Geneva in the territory of Bern, taking Rousseau's aunt Suzanne with him. Isaac Rousseau remarried, and from that point Jean-Jacques saw little of him.[5] Jean-Jacques was left in the care of his maternal uncle, who packed him, along with his own son, Abraham Bernard, Jean-Jacques's young cousin, away to board for two years with a Calvinist minister in a hamlet outside of Geneva. Here the boys picked up the elements of mathematics and drawing. Rousseau, who was always deeply moved by religious services, for a time even dreamed of being a Protestant minister himself.

Virtually all our information about Rousseau's first youth has come from his posthumously published Confessions, in which the chronology is somewhat confusing, though recent scholars have combed the archives for confirming evidence to fill in the blanks. At age thirteen Rousseau was apprenticed first to a notary and then to an engraver who beat him. At fifteen he ran away from Geneva (on March 14, 1728) after being locked out of the city walls after curfew. Not far from Geneva, in adjoining Savoy he took shelter with a Catholic priest, who introduced him to Françoise-Louise de Warens, age 29. She was a noblewoman of Protestant background who had left her husband; a lay professional proslytizer, she received an income from the King of Piedmont for helping bring Protestants to Catholicism. They sent the boy to Turin, the capital of Savoy (which included Piedmont, in what is now Italy), to complete his conversion. This resulted in his having to give up his Genevan citizenship, although he would later revert back to Calvinism in order to regain it.

In converting to Catholicism, both De Warens and Rousseau were likely reacting to the severity of Calvinism's insistence on the sinful nature of man. Leo Damrosch writes, “an eighteenth century Genevan liturgy still required believers to declare ‘that we are miserable sinners, born in corruption, inclined to evil, incapable by ourselves of doing good.’” [6] De Warens, a deist by inclination, was attracted to Catholicism's doctrine of forgiveness of sins.

Finding himself utterly alone, since his father and uncle more or less disowned him, the teenaged Rousseau supported himself for a time as a servant, secretary, and tutor, wandering in Italy (Piedmont and Savoy) and France. During this time, he he lived on and off with De Warens, whom he idolized and called his "maman". Flattered by his devotion, De Warens tried to get him started in a profession, arranging formal music lessons for him. At one point, he briefly attended a seminary with the idea of becoming a priest. When he reached twenty she took him as her lover, notwithstanding her ongoing relationship with the steward of her house. The sexual aspect of their relationship (in fact a 'Ménage à trois) confused Rousseau and made him uncomfortable, but he always considered De Warens the greatest love of his life. A rather profligate spender, she had large library and loved to entertain and listen to music. She and her circle, comprising educated members of the Catholic clergy, introduced Rousseau to the world of letters and ideas. Rousseau had been an indifferent student, but during his twenties, which were marked by long bouts of hypochondria, he began to apply himself on his own to the earnest study of philosophy, mathematics, and music, reading deeply and widely. At twenty-five, he came into a small inheritance from his mother and used a portion of it to repay De Warens for her financial support of him. At twenty-seven he took a job as a tutor in Lyon.

In 1742 Rousseau moved to Paris in order to present the Académie des Sciences with a new system of numbered musical notation. His system, intended to be compatible with typography, is based on a single line, displaying numbers representing intervals between notes and dots and commas indicating rhythmic values. Believing the system was impractical, the Academy rejected it, though they praised his mastery of the subject, and urged him to try again. (In some parts of the world[citation needed], a version of the system remains in use.)

From 1743 to 44 Rousseau had an honorable but ill-paying post as a secretary to the Comte de Montaigue, the French ambassador to Venice, to whose republican form of government Rousseau often referred in his later political works. Venice also awoke in him a life-long love for Italian music, particularly opera:

I had brought with me from Paris the prejudice of that city against Italian music; but I had also received from nature a sensibility and niceness of distinction which prejudice cannot withstand. I soon contracted that passion for Italian music with which it inspires all those who are capable of feeling its excellence. In listening to barcaroles, I found I had not yet known what singing was... --Confessions

Rousseau's employer routinely received his stipend as much a year late and was himself tardy in paying his staff.[7] There were frequent quarrels over money, and Rousseau took from the experience a profound distrust of government bureaucracy. After eleven months he quit and returned to Paris. There the penniless Rousseau befriended and became the lover of Thérèse Levasseur, a pretty seamstress who was the sole support of her termagant mother and numerous ne'er-do-well siblings. According to his Confessions, Thérèse bore him a son and as many as four other children (there is no independent corroboration for this number). Rousseau wrote that he persuaded Thérèse to give each of the newborns up to a foundling hospital, for the sake of her "honor." "Her mother, who feared the inconvenience of a brat, came to my aid, and she [Thérèse] allowed herself to be overcome" (Confessions). The foundling hospitals had been started as a reform to save the numerous infants who were being abandoned in the streets of Paris. Infant mortality at that date was extremely high -- some fifty percent, in large part because families sent their infants to be wet nursed. The mortality rate in the foundling hospitals, which also sent the babies out to be wet nursed, proved worse, however, and most of the infants sent there likely perished. Ten years later Rousseau made inquiries about the fate of his son, but no record could be found. When Rousseau subsequently became celebrated as a theorist of education and child-rearing, his abandonment of his children was used by his critics, including Voltaire and Edmund Burke, as the basis for ad hominem attacks. In an irony of fate, Rousseau's later injunction to women to breastfeed their own babies (as had previously been recommended by the French natural scientist Buffon), probably saved the lives of thousands of infants.

While in Paris, Rousseau became a close friend of French philosopher Diderot and, beginning with some articles on music in 1749,[8] contributed numerous articles to Diderot and D'Alambert's great Encyclopédie, the most famous of which was an article on political economy written in 1755.

Rousseau's ideas were the result of an almost obsessive dialog with writers of the past, filtered in many cases through conversations with Diderot. His genius lay in his strikingly original way of putting things rather than in the originality, per se, of his thinking. In 1749 Rousseau was paying daily visits to Diderot, who had been thrown into the fortress of Vincennes under a lettre de cachet for opinions in his "Lettre sur les aveugles," that hinted at materialism, a belief in atoms, and natural selection. Rousseau had read about an essay competition sponsored by the Académie de Dijon, to be published in the Mercure de France on the theme of whether the development of the arts and sciences had been morally beneficial. He wrote that while walking to Vincennes (about three miles from Paris), he had a revelation that the arts and sciences were responsible for the moral degeneration of mankind, who were basically good by nature. According to Diderot, writing much later, Rousseau had originally intended to answer this in the conventional way, but his discussions with Diderot convinced him to propose the paradoxical negative answer that catapulted him into the public eye. whatever the case, it was the great French naturalist Buffon who had first suggested, without elaborating on it, the idea that man's moral decline arose from his acquisition of property and culture. Both Rousseau and Diderot would have been aware of Buffon's speculations. Rousseau's 1750 "Discourse on the Arts and Sciences", in which he made that argument, was awarded the first prize and gained him significant fame.

Rousseau continued his interest in music, and his opera Le Devin du Village (The Village Soothsayer) was performed for King Louis XV in 1752. The king was so pleased by the work that he offered Rousseau a life-long pension. To the exasperation of his friends, Rousseau turned down the great honor, bringing him notoriety as "the man who had refused a king's pension." He also turned down several other advantageous offers, sometimes with a brusqueness bordering on truculence that gave offense and caused him problems. The same year, the visit of a troupe of Italian musicians to Paris, and their performance of Giovanni Battista Pergolesi's La Serva Padrona, prompted the Querelle des Bouffons, which pitted protagonists of French music against supporters of the Italian style. Rousseau as noted above, was an enthusiastic supporter of the Italians against Jean-Philippe Rameau and others, making an important contribution with his Letter on French Music.

On returning to Geneva in 1754, Rousseau reconverted to Calvinism and regained his official Genevan citizenship. In 1755, Rousseau completed his second major work, the Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (the Discourse on Inequality), which elaborated on the arguments of the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences.

He also pursued an important but unconsummated romantic attachment with the twenty-five-year old Sophie d'Houdetot, which partly inspired his epistolary novel, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse , also based on memories of his idyllic youthful relationship with Mme de Warens. Sophie was the cousin and house guest of Rousseau's patroness and landlady Madame d'Epinay, whom he treated rather high highhandedly. Wounded feelings gave rise to a bitter three-way quarrel between Rousseau and Madame d'Epinay; her lover, the philologist Grimm; and their mutual friend, Diderot, who took their side against Rousseau. Diderot later described Rousseau as being, "deceitful, vain as Satan, ungrateful, cruel, hypocritical, and full of malice." Rousseau, for his part, disliked the shallowness and casual atheism of the Encyclopedistes whom he met at Mme d'Epinay's table. He feared that her patronage of him reduced him to the status of a valet.

Rousseau's break with the Encyclopedistes coincided with the composition of his three major works, in all of which he emphasized his fervent belief in a spiritual origin of man's soul and the universe, in contradistinction to the materialism of Diderot, La Mettrie, and d'Holbach. During this period Rousseau enjoyed the support and patronage of the Duc de Luxembourg, and the Prince de Conti, two of the most powerful nobles in France. These men truly liked Rousseau and enjoyed his ability to converse on any subject, but they also used him as a way of getting back at Louis XV and the political faction surrounding his mistress, Mme de Pompadour. Even with them, however, Rousseau went too far, courting rejection when he criticized the practice of tax farming, in which some of them engaged.[9]

Rousseau's 800-page novel of sentiment, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, was published in (1761) to immense success. The book's rhapsodic descriptions of the natural beauty of the Swiss countryside struck a chord in the public and may have helped spark the subsequent nineteenth century craze for Alpine scenery. In 1762, Rousseau published Du Contrat Social, Principes du droit politique (in English, literally Of the Social Contract, Principles of Political Right) in April and then Émile, or On Education in May. The final section of Émile, "The Profession of Faith of a Savoyard Vicar," was intended to be a defense of religious belief. Rousseau's choice of a Catholic vicar of humble status (possibly based on someone he had known in his youth) as a spokesman for the defense of religion was in itself a daring innovation for the time. The vicar's creed was that of Socinianism (or Unitarism as it is called today). Because it rejected original sin and divine Revelation, both Protestant and Catholic authorities took offense. Moreover, Rousseau advocated the opinion that, insofar as they lead people to virtue, all religions are equally worthy, and that people should therefore conform to the religion in which they had been brought up. This religious indifferentism caused Rousseau and his books to be banned from France and Geneva. He was condemned from the pulpit by the Archbishop of Paris, and warrants were issued for his arrest.[10]

A sympathetic observer, British philosopher David Hume, "professed no surprise when he learned that Rousseau's books were banned in Geneva and elsewhere. Rousseau, he wrote, 'has not had the precaution to throw any veil over his sentiments; and, as he scorns to dissemble his contempt for established opinions, he could not wonder that all the zealots were in arms against him. The liberty of the press is not so secured in any country … as not to render such an open attack on popular prejudice somewhat dangerous.'"[11] Rousseau, who thought he had been defending religion, was crushed. Forced to flee arrest he made his way to Neuchâtel, a Canton of the Swiss Confederation that was a protectorate of the Prussian crown. His powerful protectors discretely assisted him in his flight. In the town of Môtiers, he sought and found protection under Lord Keith, who was the local representative of the free-thinking Frederick the Great of Prussia. While in Môtiers, Rousseau wrote the Constitutional Project for Corsica (Projet de Constitution pour la Corse, 1765).

After his house in Môtiers was stoned on the night of 6 September 1765, Rousseau took refuge with Hume in Great Britain. There, isolated at Wootton on the borders of Derbyshire and Staffordshire, Rousseau, never emotionally very stable, suffered a serious decline in his mental health and began to experience paranoid fantasies about plots against him involving Hume and others. “He is plainly mad, after having long been maddish”, Hume wrote to a friend.[12] Rousseau's letter to Hume, in which he articulates the perceived misconduct, sparked an exchange which was published in and received with great interest in contemporary Paris.

Although, he was not supposed to return to France before 1770, Rousseau did come back in 1767 under the name "Renou". In 1768 he went through a formal marriage of sorts to Thérèse, whom he had always hitherto referred to as his "housekeeper". Although illiterate, she had become a remarkably good cook, a hobby her husband shared. In 1770 they were allowed to return to Paris. As a condition of his return he was not allowed to publish any books, but after completing his Confessions, Rousseau began private readings in 1771. At the request of Madame d'Epinay, however, the police ordered him to stop, and the Confessions was only partially published in 1782, four years after his death. All his subsequent works were to appear posthumously.

In 1772, Rousseau was invited to present recommendations for a new constitution for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the Considerations on the Government of Poland, which was to be his last major political work. In 1776 he completed Dialogues: Rousseau Judge of Jean-Jacques and began work on the Reveries of the Solitary Walker. In order to support himself, he returned to copying music, spending his leisure time in the study of botany.

Although a celebrity, Rousseau's mental health did not permit him to enjoy his fame. His final years were largely spent in deliberate withdrawal; however, he did respond favorably to an approach from the composer Gluck, whom he met in 1774. One of Rousseau's last pieces of writing was a critical yet enthusiastic analysis of Gluck's opera Alceste. While taking a morning walk on the estate of the Marquis de Giradin at Ermenonville (28 miles northeast of Paris), Rousseau suffered a hemorrhage and died on 2 July 1778. He was sixty-six.

Rousseau was initially buried at Ermenonville on the Ile des Peupliers, which became a place of pilgrimage for his many admirers. His remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris in 1794, sixteen years after his death, where they are located directly across from those of his contemporary Voltaire. His tomb, in the shape of a rustic temple, on which, in bas relief an arm reaches out, bearing the torch of liberty, evokes Rousseau's deep love of nature and of classical antiquity. In 1834, the Genevan government somewhat reluctantly erected a statue in his honor on the tiny Île Rousseau in Lake Geneva. Today he is proudly claimed as their most celebrated native son. In 2002, the Espace Rousseau was established at 40 Grand-Rue, Geneva, Rousseau's birthplace.

Philosophy

Theory of Natural Man

The first man who, having fenced in a piece of land, said "This is mine," and found people naive enough to believe him, that man was the true founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars, and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows: Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.

— Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality, 1754

In common with other philosophers of the day, Rousseau looked to a hypothetical State of Nature as a normative guide. Rousseau deplores Hobbes for asserting that since man in the "state of nature . . . has no idea of goodness he must be naturally wicked; that he is vicious because he does not know virtue". On the contrary, Rousseau holds that "uncorrupted morals" prevail in the "state of nature" and he especially praised the admirable moderation of the Caribbeans in expressing the sexual urge.[13] despite the fact that they live in a hot climate, which "always seems to inflame the passions".[14] This has led Anglophone critics to erroneously attribute to Rousseau the invention of idea of the noble savage, an oxymoronic expression that was never used in France and which grossly misrepresents Rousseau's thought.[15] (The expression, "the noble savage" was first used in 1672 by British poet John Dryden in his play The Conquest of Granada. The French word "sauvage" means "wild", as in "a wild flower", and does not have the connotations of fierceness or brutality that the word "savage" does in English.) Rousseau did deny that morality is a construct or creation of society. He considered it as "natural" in the sense of "innate", an outgrowth of man's instinctive disinclination to witness suffering, from which arise the emotions of compassion or empathy, sentiments whose existence even Hobbes acknowledged, and which are shared with animals.[16]

Contrary to what his many detractors have claimed on the basis of casual readings, Rousseau never suggests that humans in the state of nature act morally; in fact, terms such as "justice" or "wickedness" are inapplicable to pre-political society as Rousseau understands it. Morality proper, i.e., self restraint, can only develop through careful education in a civil state. Humans "in a state of Nature" may act with all of the ferocity of an animal. They are good only in a negative sense, insofar as they are self-sufficient and thus not subject to the vices of political society. In fact, Rousseau's natural man is virtually identical to a solitary chimpanzee or other ape, such as the Orangutang as described by Buffon; and the "natural" goodness of humanity is thus the goodness of an animal, which is neither good nor bad. Rousseau, a deteriorationist, proposed that, except perhaps for brief moments of balance, at or near its inception, when a relative equality among men prevailed, human civilization has always been artificial, creating inequality, envy, and unnatural desires.

In Rousseau's philosophy, society's negative influence on men centers on its transformation of amour de soi, a positive self-love, into amour-propre, or pride. Amour de soi represents the instinctive human desire for self-preservation, combined with the human power of reason. In contrast, amour-propre is artificial and encourages man to compare himself to others, thus creating unwarranted fear and allowing men to take pleasure in the pain or weakness of others. Rousseau was not the first to make this distinction; it had been invoked by, among others, Vauvenargues.

In Discourse on the Arts and Sciences Rousseau argues that the arts and sciences have not been beneficial to humankind because they arose, not from authentic human needs, but rather as a result of pride and vanity. Moreover, the opportunities they create for idleness and luxury have contributed to the corruption of man. He proposed that the progress of knowledge had made governments more powerful and had crushed individual liberty; and he concluded that material progress had actually undermined the possibility of true friendship by replacing it with jealousy, fear and suspicion.

In contrast to the optimistic view of some Enlightenment figures, for Rousseau, progress [2] has been inimical to the well-being of humanity, that is unless it can be counteracted by the cultivation of civic morality and duty. Only in civil society, can man be ennobled -- through the use of reason:

The passage from the state of nature to the civil state produces a very remarkable change in man, by substituting justice for instinct in his conduct, and giving his actions the morality they had formerly lacked. Then only, when the voice of duty takes the place of physical impulses and right of appetite, does man, who so far had considered only himself, find that he is forced to act on different principles, and to consult his reason before listening to his inclinations. Although, in this state, he deprives himself of some advantages which he got from nature, he gains in return others so great, his faculties are so stimulated and developed, his ideas so extended, his feelings so ennobled, and his whole soul so uplifted, that, did not the abuses of this new condition often degrade him below that which he left, he would be bound to bless continually the happy moment which took him from it for ever, and, instead of a stupid and unimaginative animal, made him an intelligent being and a man.[17]

Society corrupts men only insofar as the Social Contract has not de facto succeeded, as we see in contemporary society as described in the Discourse on Inequality. There is no inconsistency but rather a strong unity in Rousseau's thought.

Rousseau's subsequent Discourse on Inequality traced the evolution of mankind from a primitive state of nature to modern society. He suggested that the earliest human beings were solitary and differentiated from animals by their capacity for free will and their potential perfectibility. He also argued that these primitive humans were possessed of a basic drive to care for themselves and a natural disposition to compassion or pity. As the pressure of population forced humans to associate together more closely they underwent a psychological transformation as they came to value the good opinion of others as an essential component of their own well-being. Rousseau associated this new self-awareness with a fleeting golden age of human flourishing. However, the development of agriculture, metallurgy, private property, and the division of labour and resulting dependency on one another led to economic inequality. The resulting state of conflict led Rousseau to suggest that the first, deeply flawed, Social Contract, which lead to the modern state, was made at the suggestion of the rich and powerful, who tricked the general population into surrendering their liberties to them, thus instituting inequality as a fundamental feature of human society. Rousseau's own conception of the Social Contract can be understood as an alternative to this fraudulent form of association. At the end of the Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau explains how the desire to have value in the eyes of others comes to undermine personal integrity and authenticity in a society marked by interdependence, hierarchy, and inequality. (In the last chapter of the Social Contract, Rousseau would ask "What is to be done?" and answers that all men could do is to cultivate virtue in themselves and submit to their lawful rulers. To his readers, however the inescapable conclusion was that a new and more equitable Social Contract was needed, one that was based on the consent of the governed.)

Political theory

Perhaps Jean Jacques Rousseau's most important work is The Social Contract, which outlines the basis for a legitimate political order within a framework of classical republicanism. Published in 1762, it became one of the most influential works of political philosophy in the Western tradition. It developed some of the ideas mentioned in an earlier work, the article Economie Politique (Discourse on Political Economy), featured in Diderot's Encyclopédie. The treatise begins with the dramatic opening lines, "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. One man thinks himself the master of others, but remains more of a slave than they." Rousseau claimed that the state of nature was a primitive condition without law or morality, which human beings left for the benefits and necessity of cooperation. As society developed, division of labor and private property required the human race to adopt institutions of law. In the degenerate phase of society, man is prone to be in frequent competition with his fellow men while at the same time becoming increasingly dependent on them. This double pressure threatens both his survival and his freedom. According to Rousseau, by joining together into civil society through the social contract and abandoning their claims of natural right, individuals can both preserve themselves and remain free. This is because submission to the authority of the general will of the people as a whole guarantees individuals against being subordinated to the wills of others and also ensures that they obey themselves because they are, collectively, the authors of the law.

Although Rousseau argues that sovereignty (or the power to make the laws) should be in the hands of the people, he also makes a sharp distinction between the sovereign and the government. The government is composed of magistrates, charged with implementing and enforcing the general will. The "sovereign" is the rule of law, ideally decided on by direct democracy in an assembly. Under a monarchy, however, the real sovereign is still the law. Rousseau was opposed to the idea that the people should exercise sovereignty via a representative assemblyTemplate:Citation needed February 2009. The kind of republican government of which Rousseau approved was that of the city state, of which Geneva, was a model, or would have been, if renewed on Rousseau's principles. France could not meet Rousseau's criterion of an ideal state because it was too big. Much subsequent controversy about Rousseau's work has hinged on disagreements concerning his claims that citizens constrained to obey the general will are thereby rendered free:

The notion of the general will is wholly central to Rousseau's theory of political legitimacy ... It is, however, an unfortunately obscure and controversial notion. Some commentators see it as no more than the dictatorship of the proletariat or the tyranny of the urban poor (such as may perhaps be seen in the French Revolution). Such was not Rousseau's meaning. This is clear from the Discourse on Political Economy, where Rousseau emphasizes that the general will exists to protect individuals against the mass, not to require them to be sacrificed to it. He is, of course, sharply aware that men have selfish and sectional interests which will lead them to try to oppress others. It is for this reason that loyalty to the good of all alike must be a supreme (although not exclusive) commitment by everyone, not only if a truly general will is to be heeded but also if it is to be formulated successfully in the first place".[18]

Education and Child Rearing

Rousseau’s philosophy of education is not concerned with particular techniques of imparting information and concepts, but rather with developing the pupil’s character and moral sense, so that he may learn to practice self-mastery and remain virtuous even in the unnatural and imperfect society in which will have to live. The hypothetical boy, Émile, is to be raised in the countryside, which, Rousseau believes, is a more natural and healthy environment than the city, under the guardianship of a tutor who will guide him through various learning experiences arranged by the tutor. Today we would call this the disciplinary method of "logical consequences", since like modern psychologists, Rousseau felt that children learn right and wrong through experiencing the consequences of their acts rather than through physical punishment. The tutor will make sure than no harm results to Émile through his learning experiences.

Rousseau was one of the first to advocate developmentally appropriate education; and his description of the stages of child development mirrors his conception of the evolution of culture. He divides childhood into stages: the first is to the age of about 12, when children are guided by their emotions and impulses. During the second stage, from 12 to about 16, reason starts to develop; and finally the third stage, from the age of 16 onwards, when the child develops into an adult. Rousseau recommends that the young adult should learn a manual skill such as carpentry, which requires creativity and thought, will keep him out of trouble, and will supply a fallback means of making a living in the event of a change of fortune. (The most illustrious aristocratic youth to have been educated this way may have been Louis XVI, whose parents had him learn the skill of locksmithing, though he was beheaded before he had a chance to use it.) The sixteen-year old is also ready to have a companion of the opposite sex.

Although his ideas foreshadowed modern ones in many ways, in one way they do not: Rousseau was a believer in the moral superiority of the patriarchal family on the antique Roman model. Sophie, the young woman Émile is destined to marry, as a representative of ideal womanhood, is educated to be governed by her husband while Émile, as representative of the ideal man, is educated to be self-governing. This is not an accidental feature of Rousseau's educational and political philosophy; it is essential to his account of the distinction between private, personal relations and the public world of political relations. The private sphere as Rousseau imagines it depends on the subordination of women, in order for both it and the public political sphere (upon which it depends) to function as Rousseau imagines it could and should. Rousseau anticipated the modern idea of the bourgeois nuclear family, with the mother at home taking responsibility for the household and for childcare and early education.

Feminists, beginning in the nineteenth century with Mary Wollstonecraft have criticized Rousseau for his confinement of women to the domestic sphere, but his contemporaries saw it differently.

Rousseau made a point on insisting that mothers should breastfeed their children instead of consigning them to wet nurses, and mothers listened. ’We all said it,’ the great naturalist Buffon remarked, ‘but M. Rousseau alone commanded it and made himself obeyed.’ Long after his death, women held him in high esteem on this score. Marmontel describes a near disaster his infant son suffered when given to a wet nurse who starved him, and said that his wife could never accept his constant denigration of Rousseau; she felt infinite gratitude for his persuading women to nurse their infants, and for taking care to make the first stage of life happy. "One must forgive something," she said, "in one who has taught us to be mothers."[19]

Rousseau's detractors have blamed him for everything they do not like in what they call modern "child-centered" education. John Darling's 1994 book Child-Centered Education and its Critics argues that the history of modern educational theory is a series of footnotes to Rousseau, a development he regards as bad. Good or bad, the theories of educators such as Rousseau's near contemporaries Pestalozzi, Mme de Genliss, and later, Maria Montessori, and Dewey, which have directly influenced modern educational practices do have significant points in common with those of Rousseau.

Religion

Although, unlike many of the more radical Enlightenment philosophers, Rousseau affirmed the necessity of religion, he repudiated the doctrine of original sin, which plays so large a part in Calvinism (in Émile, Rousseau writes "there is no original perversity in the human heart").[20]

In the eighteenth century, many deists viewed God merely an abstract and impersonal creator of the universe, which they likened to a giant machine. Rousseau's deism differed from the usual kind in its intense emotionality. He saw the presence of God in His creation, including mankind, which, apart from the harmful influence of society, is good, because God is good. Rousseau's acceptance of the argument of intelligent design and his explicit attribution of a spiritual value to the beauty of nature anticipates the attitudes of nineteenth-century Romanticism towards nature and religion.

At the time, however, Rousseau's strong endorsement of religious toleration, as expounded by the Savoyard vicar in Émile, was interpreted as advocating indifferentism, a heresy, and led to the condemnation of the book in both Calvinist Geneva and Catholic Paris. His assertion in the Social Contract that true followers of Jesus would not make good citizens may have been another reason for Rousseau's condemnation in Geneva.

Rousseau was upset that his deistic views were so forcefully condemned, while those of the more frankly atheistic philosophes were ignored. He defended himself against critics of his religious views in his "Letter to Christophe de Beaumont, the Archbishop of Paris.".[21]

Legacy

Rousseau's idea of the volonté générale ("general will") was not original with him but rather belonged to a well-established technical vocabulary of juridical and theological writings in use at the time. The phrase was used by Montesquieu (and by his teacher Malebranche), and also by Diderot. It served to designate the common interest embodied in legal tradition, as distinct from and transcending people's private and particular interests at any particular time. The concept was also an important aspect of the more radical seventeenth century republican tradition of Spinoza, from whom Rousseau differed in important respects, but not in his insistence on the importance of equality. This emphasis on equality is Rousseau's most important and consequential legacy, causing him to be both reviled and applauded:

While Rousseau's notion of the progressive moral degeneration of mankind from the moment civil society established itself diverges markedly from Spinoza's claim that human nature is always and everywhere the same . . . for both philosophers the pristine equality of the state of nature is our ultimate goal and criterion . . . in shaping the "common good", volonté générale, or Spinoza's mens una, which alone can ensure stability and political salvation. Without the supreme criterion of equality, the general will would indeed be meaningless. .. . When in the depths of the French Revolution the Jacobin clubs all over France regularly deployed Rousseau when demanding radical reforms. and especially anything -- such as land redistribution -- designed to enhance equality, they were at the same time, albeit unconsciously, invoking a radical tradition which reached back to the late seventeenth century.[22]

The cult that grew up around Rousseau after his death, and particularly the radicalized versions of Rousseau's ideas that were adopted by Robespierre and Saint Just during the Reign of Terror, caused him to become identified with the most extreme aspects of the French Revolution.[23] The revolutionaries were also inspired by Rousseau to introduce deism as the new official civic religion of France, scandalizing traditionalists:

Ceremonial and symbolic occurrences of the more radical phases of the Revolution invoked Rousseau and his core ideas. Thus the ceremony held at the site of the demolished Bastille, organized by the foremost artistic director of the Revolution, Jacques-Louis David, in August 1793 to mark the inauguration of the new republican constitution, an event coming shortly after the final abolition of all forms of feudal privilege, featured a cantata based on Rousseau's democratic pantheistic deism as expounded in the celebrated "Profession de foi d'un vicaire savoyard" in Book four of Émile.[24]

. Critics of the Revolution and defenders of religion, most influentially the Irish essayist Edmund Burke, therefore placed the blame for the excesses of the French Revolution directly on the revolutionaries' misplaced (as he considered it) adulation of Rousseau. Burke's "Letter to a Member of the National Assembly", published in February 1791, was a diatribe against Rousseau, whom he considered the paramount influence on French Revolution (his ad hominem attack did not really engage with Rousseau's political writings). Burke maintained that the excesses of the Revolution were not accidents but were designed from the beginning and were rooted in Rousseau's personal vanity, arrogance, and other moral failings. He recalled Rousseau's visit to Britain in 1766, saying: "I had good opportunities of knowing his proceedings almost from day to day and he left no doubt in my mind that he entertained no principle either to influence his heart or to guide his understanding, but vanity". Conceding his gift of eloquence, Burke deplored Rousseau's lack of the good taste and finer feelings that would have been imparted by the education of a gentleman:

Taste and elegance . . . are of no mean importance in the regulation of life. A moral taste. . .infinitely abates the evils of vice. Rousseau, a writer of great force and vivacity, is totally destitute of taste in any sense of the word. Your masters [i.e., the leaders of the Revolution], who are his scholars, conceive that all refinement has an aristocratic character. The last age had exhausted all its powers in giving a grace and nobleness to our mutual appetites, and in raising them into a higher class and order than seemed justly to belong to them. Through Rousseau, your masters are resolved to destroy these aristocratic prejudices.[25]

In America, where there was no such cult, the direct influence of Rousseau was arguably less. The American founders did share Rousseau's enthusiastic admiration for the austere virtues described by Livy and in Plutarch's portrayals of ancient Sparta and the classical republicanism of early Rome, but so did most other enlightenment figures. Rousseau’s praise of Switzerland and Corsica’s economies of isolated and self-sufficient independent homesteads, and his endorsement of a well-regulated citizen militia, such as Switzerland’s, recalls the Jeffersonian ideal. Yet despite their mutual insistence on the self evidence that "all men are created equal", their insistence that the citizens of a republic must be educated at public expense, and the evident parallel between the concepts of the "general welfare" and Rousseau's "general will", there is little to suggest that Rousseau had that much impact on Thomas Jefferson and other founding fathers. The American constitution owes more to the English Liberal philosopher John Locke's emphasis on the rights of property and to Montesquieu's theories of the separation of powers.[26] Rousseau did arguably have some indirect influence on American literature, through the writings of Wordsworth and Kant, on the New England Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson, and his disciple Henry David Thoreau, as well as on such Unitarians as theologian William Ellery Channing, not to mention novelist James Fenimore Cooper.[27]

Criticisms

Following the French Revolution, critics fingered a potential danger of Rousseau’s project of realizing an “antique” conception of virtue amongst the citizenry in a modern world (e.g. through education, physical exercise, a citizen militia, public holidays, and the like). Taken too far, as under the Jacobins, such social engineering could result in tyranny. This criticism of Rousseau came to be known among scholars as the "totalitarian thesis" ("totalitarian" being a word that was invented by during the reign of Mussolini), and is now regarded by Rousseau scholars as discredited. An modern example is J. L. Talmon's, The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy (1952)[28]

As early as 1819, in his famous speech “On Ancient and Modern Liberty,” the political philosopher Benjamin Constant, a proponent of constitutional monarchy, criticized Rousseau, or more accurately his French Revolutionary followers, for allegedly believing that "everything should give way to collective will, and that all restrictions on individual rights would be amply compensated by participation in social power.”

Common also were attacks by defenders of social hierarchy on Rousseau's "romantic" belief in equality. In 1860, shortly after the Sepoy Rebellion in India, two British white supremacists, John Crawfurd and James Hunt mounted a defense of British imperialism based on “scientific racism".[29] Crawfurd, in alliance with Hunt, took over the presidency of the British Anthropological Society, which had hitherto defended indigenous peoples against colonial exploitation. The two men derided their "philanthropic" predecessors for believing in human equality and for not recognizing the that the races were divided into superior and inferior races. Crawfurd, who opposed Darwinian evolution, "denied any unity to mankind, insisting on immutable, hereditary, and timeless differences in racial character, principal amongst which was the 'very great' difference in 'intellectual capacity.'" For Crawfurd, the races had been created separately and were different species. Since Crawfurd was Scots, he thought the Scots race reigned supreme and all others were inferior; whilst Hunt, on the other hand, believed in the supremacy of the English "race". Crawfurd and Hunt routinely accused those who disagreed with them of believing in "Rousseau’s Noble Savage". (The pair ultimately quarreled because Hunt believed in slavery and Crawfurd did not). "As Ter Ellinson demonstrates, Crawfurd was responsible for re-introducing the Pre-Rousseauian concept of 'the Noble Savage' to modern anthropology, attributing it wrongly and quite deliberately to Rousseau.”[30]

In the twentieth century, the French fascist theorist and anti-Semite Charles Maurras, founder of Action Française, “had no compunctions in laying the blame for both Romantisme et Révolution firmly on Rousseau in 1922." [31]

Political scientist J. S. Moloy states that “the twentieth century added Nazism and Stalinism to Jacobinism on the list of horrors for which Rousseau could be blamed. ... Rousseau was considered to have advocated just the sort of invasive tampering with human nature which the totalitarian regimes of mid-century had tried to instantiate." But he adds that "The totalitarian thesis in Rousseau studies has, by now, been discredited as an attribution of real historical influence.” [32]

See also

- Age of Enlightenment

- Classical republicanism

- civil militia

- Deism

- Georges Hébert, a physical culturist influenced by Rousseau's teachings

- Natural rights

- Rousseau's educational philosophy

- Rousseau Institute

- Social Contract

- State of Nature

Notes

- ^ "Preromanticism Criticism". Enotes.com. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- ^ See also Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre, chapter 6: "Readers Respond to Rousseau: The Fabrication of Romantic Sensitivity" for some interesting examples of contemporary reactions to this novel.

- ^ Leo Damrosch, Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2005) p. 31.

- ^ "And indeed, a British visitor commented, ‘Even the lower class of people [of Geneva] are exceedingly well informed, and there is perhaps no city in Europe where learning is more universally diffused.’ another at mid-century noticed that Genevan workmen were fond of reading the works of Locke and Montesquieu,” see Leo Damrosch,Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius, p. 14.

- ^ Damrosch, p. 24.

- ^ Rouseau: Restless Genius, p. 121.

- ^ Leo Damrosch describes the count as “a virtual parody of a parasitic aristocrat, incredibly stupid, irascible, and swollen with self importance." He spoke no Italian, a language in which Rousseau was fluent. Although Rousseau did most of the work of the embassy, he was treated like valet (see Damrosch, p. 168).

- ^ Rousseau in his musical articles in the Encyclopedie engaged in lively controversy with other musicians, e.g. with Rameau, as in his article on Temperament, for which see Encyclopédie: Tempérament (English translation), also Temperament Ordinaire.

- ^ Damrosch, p. 357.

- ^ Rousseau's biographer Leo Damrosch, believes that the authorities chose to condemn him on religious rather than political grounds for tactical reasons. See Damrosch Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Restless Genius (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2005).

- ^ Peter Gay, The Enlightenment, The Science of Freedom, p. 72.

- ^ Quoted in Damrosch, p. 432

- ^ Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality, 72-73

- ^ Discourse, 78.

- ^ See A. O. Lovejoy's essay on "The Suppposed Primitivism of Rousseau's Discourse on Inequality" in Essays in the History of Ideas (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1948, 1960). For a history of how the phrase became associated with Rousseau, see Ter Ellinson's, The Myth of the Noble Savage (Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 2001)

- ^ In locating the basis of ethics in emotions rather than reason Rousseau agreed with Adam Smith's 1759 Theory of Moral Sentiments.

- ^ The Social Contract, Book I Chapter 8 [1]

- ^ Entry, "Rousseau" in the Routelege Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward Craig, editor, Volume Eight, p. 371

- ^ Damrosch, p. 341-42.

- ^ il n’y a point de perversité originelle dans le cœur humain http://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Émile,_ou_De_l’éducation_-_Livre_second

- ^ The full text of the letter is available online only in the French original: Lettre à Mgr De Beaumont Archevêque de Paris (1762)

- ^ Jonathan I. Israel, Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity (Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 274.

- ^ Robspierre and Saint-Just's conception of L’intérêt général or the will of the people was derived from Rousseau's "general will", and they considered themselves "highly principled republicans, charged with stripping away what was superfluous and corrupt, inspired above all by Rousseau", Jonathan Israel, p. 717.

- ^ Jonathan Israel, p. 717.

- ^ Edmund Burke. "A letter to a member of the National Assembly, 1791". Ourcivilisation.com. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- ^ A case for Rousseau as an enemy of the Enlightenment is made in Graeme Garrard, Rousseau's Counter-Enlightenment: A Republican Critique of the Philosophes (Albany: SUNY Press, 2003).

- ^ "Rousseau, whose romantic and egalitarian tenets had practically no influence on the course of Jefferson's, or indeed any American, thought." Nathan Schachner, Thomas Jefferson: A Biography. (1957). p. 47. One admirer was lexicographer Noah Webster. Mark J. Temmer, "Rousseau and Thoreau," Yale French Studies, No. 28, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1961), pp. 112-121.

- ^ Talmon's thesis was refuted by Ralph A. Leigh in “Liberté et autorité dans le Contrat Social”in Jean-Jacques Rousseau et son ouevre (Paris 1963).

- ^ see Ter Ellingson, The Myth of the Noble Savage, 2001.

- ^ "John Crawfurd — 'two separate races'". Epress.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- ^ See R. Simon Harvey, who goes on: "and mere concern for the facts has not inhibited others from doing likewise. Irving Babbitt’s Rousseau & Romanticism still remains the only general work on this subject though printed as long ago as 1919, but it is grossly inaccurate, discursive and biased ….”See Reappraisals of Rousseau: studies in honor of R. A. Leigh, R, Simon Harvey, Editor (Manchester University press. 1980).

- ^ J. S. Maloy, “The Very Order of Things: Rousseau's Tutorial Republicanism,” Polity, Vol. 37 (2005)

References

- Abizadeh, Arash (2001). "Banishing the Particular: Rousseau on Rhetoric, Patrie, and the Passions" Political Theory 29.4: 556-82.

- Bertram, Christopher (2003). Rousseau and The Social Contract. London: Routledge.

- Cassirer Ernst, Rousseau, Kant, Goethe, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1945.

- Conrad, Felicity (2008). "Rousseau Gets Spanked, or, Chomsky's Revenge." The Journal of POLI 433. 1.1: 1-24.

- Cooper, Laurence (1999).Rousseau, Nature and the Problem of the Good Life. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Cottret, Monique, Cottret, Bernard, Jean-Jacques Rousseau en son temps, Paris, Perrin, 2005.

- Cranston, Maurice (1982). Jean-Jacques: The Early Life and Work. New York: Norton.

- Cranston, Maurice (1991). The Noble Savage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Cranston, Maurice (1997). The Solitary Self. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Damrosch, Leo (2005). Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Dent, N.J.H. (1988). Rousseau : An Introduction to his Psychological, Social, and Political Theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Dent, N.J.H. (1992). A Rousseau Dictionary. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Dent, N.J.H. (2005). Rousseau. London: Routledge.

- Derrida, Jacques (1976). Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Einaudi, Mario. (1968). Early Rousseau. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Farrell, John (2006). Paranoia and Modernity: Cervantes to Rousseau. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Garrard, Graeme (2003). Rousseau's Counter-Enlightenment: A Republican Critique of the Philosophes. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Gauthier, David (2006). Rousseau: The Sentiment of Existence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- LaFreniere, Gilbert F. (1990) "Rousseau and the European Roots of Environmentalism." Environmental History Review 14 (No. 4): 41-72

- Lange, Lynda (2002). Feminist Interpretations of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. University Park: Penn State University Press.

- Marks, Jonathan (2005). Perfection and Disharmony in the Thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Melzer, Arthur (1990). The Natural Goodness of Man: On the System of Rousseau's Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pateman, Carole (1979). The Problem of Political Obligation: A Critical Analysis of Liberal Theory. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Riley, Patrick (ed.) (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Rousseau. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Robinson, Dave & Groves, Judy (2003). Introducing Political Philosophy. Icon Books. ISBN 1-84046-450-X.

- Scott, John, T., editor (2006). Jean Jacques Rousseau, Volume 3: Critical Assessments of Leading Political Philosophers. New York: Routledge.

- Simpson, Matthew (2006). Rousseau's Theory of Freedom. London: Continuum Books.

- Simpson, Matthew (2007). Rousseau: Guide for the Perplexed. London: Continuum Books.

- Starobinski, Jean (1988). Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Transparency and Obstruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Strauss, Leo (1953). Natural Right and History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, chap. 6A.

- Strauss, Leo (1947). "On the Intention of Rousseau," Social Research 14: 455-87.

- Strong, Tracy B. (2002). Jean Jacques Rousseau and the Politics of the Ordinary. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Williams, David Lay (2007). Rousseau’s Platonic Enlightenment. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Wokler, Robert (1995). Rousseau. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Major works

- Dissertation sur la musique moderne, 1736

- Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (Discours sur les sciences et les arts), 1750

- Narcissus, or The Self-Admirer: A Comedy, 1752

- Le Devin du Village: an opera, 1752, Template:PDFlink

- Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes), 1754

- Discourse on Political Economy, 1755

- Letter to M. D'Alembert on Spectacles, 1758 (Lettre à d'Alembert sur les spectacles)

- Julie, or the New Heloise (Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse), 1761

- Émile: or, on Education (Émile ou de l'éducation), 1762

- The Creed of a Savoyard Priest, 1762 (in Émile)

- The Social Contract, or Principles of Political Right (Du contrat social), 1762

- Four Letters to M. de Malesherbes, 1762

- Pygmalion: a Lyric Scene, 1762

- Letters Written from the Mountain, 1764 (Lettres de la montagne)

- Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Les Confessions), 1770, published 1782

- Constitutional Project for Corsica, 1772

- Considerations on the Government of Poland, 1772

- Essay on the origin of language, published 1781 (Essai sur l'origine des langues)

- Reveries of a Solitary Walker, incomplete, published 1782 (Rêveries du promeneur solitaire)

- Dialogues: Rousseau Judge of Jean-Jacques, published 1782

Editions in English

- Basic Political Writings, trans. Donald A. Cress. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1987.

- Collected Writings, ed. Roger D. Masters and Christopher Kelly, Dartmouth: University Press of New England, 1990-2005, 11 vols. (Does not as yet include Émile.)

- The Confessions, trans. Angela Scholar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Emile, or On Education, trans. with an introd. by Allan Bloom, New York: Basic Books, 1979.

- "On the Origin of Language," trans. John H. Moran. In On the Origin of Language: Two Essays. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Reveries of a Solitary Walker, trans. Peter France. London: Penguin Books, 1980.

- 'The Discourses' and Other Early Political Writings, trans. Victor Gourevitch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- 'The Social Contract' and Other Later Political Writings, trans. Victor Gourevitch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- 'The Social Contract, trans. Maurice Cranston. Penguin: Penguin Classics Various Editions, 1968-2007.

- The Political writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, edited from the original MCS and authentic editions with introduction and notes by C.E.Vaughan, Blackwell, Oxford, 1962. (In French but the introduction and notes are in English).

Online texts

- A Discourse on the Moral Effects of the Arts and Sciences English translation

- Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau English translation, as published by Project Gutenberg, 2004 [EBook #3913]

- Considerations on the Government of Poland English translation

- Constitutional Project for Corsica English translation

- Discourse on Political Economy English translation

- Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men English translation

- Du contrat social at MetaLibri Digital Library.

- Template:PDFlink English translation

- Emile French text and English translation (Grace G. Roosevelt's revision and correction of Barbara Foxley's Everyman translation, at Columbia)

- Full Ebooks of Rousseau in french on the website 'La philosophie'

- Mondo Politico Library's presentation of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's book, The Social Contract (G.D.H. Cole translation; full text)

- Narcissus, or The Self-Admirer: A Comedy English translation

- Project Concerning New Symbols for Music French text and English translation

- The Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- The Creed of a Savoyard Priest English translation

- The Social Contract, Or Principles of Political Right English translation

- Works by Jean-Jacques Rousseau at Project Gutenberg

External links

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau Bibliography

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau page at Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Rousseau Association/Association Rousseau, a bilingual association Template:En icon Template:Fr icon devoted to the study of Rousseau's life and works

- Edward Winter, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Chess

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, at the Internet edition of Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Template:Persondata

{{subst:#if:Rousseau, Jean-Jacques|}}

[[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1712}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1778}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1712 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1778}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

- Living people

- 1778 deaths

- 18th-century philosophers

- Alternative education

- Autobiographers

- Burials at the Panthéon

- Early modern philosophers

- Encyclopedists

- Enlightenment philosophers

- French memoirists

- French music theorists

- French novelists

- French people of Swiss descent

- French Roman Catholics

- People from Geneva

- Philosophes

- Political theorists

- Swiss educationists

- Swiss memoirists

- Swiss music theorists

- Swiss novelists

- Swiss philosophers

- Swiss vegetarians

- French republicans

- French political philosophers