Graves' disease

| Graves' disease | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Graves' disease is an autoimmune disease. It most commonly affects the thyroid, causing it to grow to twice its size or more (goiter), be overactive, with related hyperthyroid symptoms such as increased heartbeat, muscle weakness, disturbed sleep, and irritability. It can also affect the eyes, causing bulging eyes (exophthalmos). It affects other systems of the body, including the skin and reproductive organs. It affects up to 2% of the female population, often appears after childbirth, and has a female:male incidence of 5:1 to 10:1. It has a strong hereditary component; when one identical twin has Graves' disease, the other twin will have it 25% of the time. Smoking is associated with the eye manifestations but not the thyroid manifestations. Diagnosis is usually made on the basis of symptoms, although thyroid hormone tests may be useful, particularly to monitor treatment.[1]

History

Graves' disease owes its name to the Irish doctor Robert James Graves ,[2] who described a case of goiter with exophthalmos in 1835.[3] However, the German Karl Adolph von Basedow independently reported the same constellation of symptoms in 1840.[4][5] As a result, on the European Continent, the terms Basedow's syndrome[6], or Basedow's disease[7] are more common than Graves' disease.[6][8]

Graves' disease[7][6] has also been called exophthalmic goiter[7]

Less commonly, it has been known as Parry's disease[7][6], Begbie's disease, Flajani's disease, Flajani-Basedow syndrome, and Marsh's disease.[6] The names Grave's disease and Parry's disease were based also on other pioneer investigators of the disorder, namely: Robert James Graves and Caleb Hillier Parry, respectively. The rest of the other names for the disease were derived from James Begbie, Giuseppe Flajani, and Henry Marsh.[6] The other names are from several earlier reports that exist but were not widely circulated. For example, cases of goiter with exophthalmos were published by the Italians Giuseppe Flajina[9] and Antonio Giuseppe Testa,[10] in 1802 and 1810, respectively.[11] Prior to these, Caleb Hillier Parry,[12] a notable provincial physician in England of the late 18th century (and a friend of Edward Miller-Gallus),[13] described a case in 1786. This case was not published until 1825, but still 10 years ahead of Graves.[14]

However, fair credit for the first description of Graves' disease goes to the 12th century Persian physician Sayyid Ismail al-Jurjani,[15] who noted the association of goiter and exophthalmos in his "Thesaurus of the Shah of Khwarazm", the major medical dictionary of its time.[6][16][17]

Diagnosis

Graves' disease may present clinically with one of the following characteristic signs:

- exophthalmos (protuberance of one or both eyes)

- a non-pitting edema (pretibial myxedema), with thickening of the skin usually found on the lower extremities

- fatigue, weight loss with increased appetite, and other symptoms of hyperthyroidism

- rapid heart beats

- muscular weakness

The two signs that are truly 'diagnostic' of Graves' disease (i.e., not seen in other hyperthyroid conditions) are exophthalmos and non-pitting edema (pretibial myxedema). Goiter is an enlarged thyroid gland and is of the diffuse type (i.e., spread throughout the gland). Diffuse goiter may be seen with other causes of hyperthyroidism, although Graves' disease is the most common cause of diffuse goiter. A large goiter will be visible to the naked eye, but a smaller goiter (very mild enlargement of the gland) may be detectable only by physical exam. Occasionally, goiter is not clinically detectable but may be seen only with CT or ultrasound examination of the thyroid.

Another sign of Graves' disease is hyperthyroidism, i.e., overproduction of the thyroid hormones T3 and T4. Normothyroidism is also seen, and occasionally also hypothyroidism, which may assist in causing goiter (though it is not the cause of the Graves disease). Hyperthyroidism in Graves' disease is confirmed, as with any other cause of hyperthyroidism, by measuring elevated blood levels of free (unbound) T3 and T4.

Other useful laboratory measurements in Graves' disease include thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH, usually low in Graves' disease due to negative feedback from the elevated T3 and T4), and protein-bound iodine (elevated). Thyroid-stimulating antibodies may also be detected serologically.

Biopsy to obtain histiological testing is not normally required but may be obtained if thyroidectomy is performed.

Differentiating two common forms of hyperthyroidism such as Graves' disease and Toxic multinodular goiter is important to determine proper treatment. Measuring TSH-receptor antibodies with the h-TBII assay has been proven efficient and was the most practical approach found in one study.[18]

Eye disease

Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy is one of the most typical symptoms of Graves' disease. It is known by a variety of terms, the most common being Graves' ophthalmopathy. Thyroid eye disease is an inflammatory condition, which affects the orbital contents including the extraocular muscles and orbital fat. It is almost always associated with Graves' disease but may rarely be seen in Hashimoto's thyroiditis, primary hypothyroidism, or thyroid cancer.

The ocular manifestations that are relatively specific to Grave's disease include soft tissue inflammation, proptosis (protrusion of one or both globes of the eyes), corneal exposure, and optic nerve compression. Also seen, if the patient is hyperthyroid, (i.e., has too much thryoid hormone) are more general manifestations, which are due to hyperthyroidism itself and which may be seen in any conditions that cause hyperthyroidism (such as toxic multinodular goiter or even thyroid poisoning). These more general symptoms include lid retraction, lid lag, and a delay in the downward excursion of the upper eyelid, during downward gaze.

It is believed that fibroblasts in the orbital tissues may express the Thyroid Stimulating Hormone receptor (TSHr). This may explain why one autoantibody to the TSHr can cause disease in both the thyroid and the eyes. [19]

Classification of Graves Eye Disease

Mnemonic: "NO SPECS":[20]

Class 0: No signs or symptoms

Class 1: Only signs (limited to upper lid retraction and stare, with or without lid lag)

Class 2: Soft tissue involvement (oedema of conjunctivae and lids, conjunctival injection, etc)

Class 3: Proptosis

Class 4: Extraocular muscle involvement (usually with diplopia)

Class 5: Corneal involvement (primarily due to lagophthalmos)

Class 6: Sight loss (due to optic nerve involvement)

Treatment specific to eye problems

- For mild disease - artificial tears, steroids (to reduce chemosis)

- For moderate disease - lateral tarsorrhaphy

- For severe disease - orbital decompression or retro-orbital radiation

Other Graves' disease symptoms

Some of the most typical symptoms of Graves' Disease are included in the the following list. All but the eye-related problems and goitre are due to the effects of too much thyroid hormone, and are seen in other hyperthyroid states, including simple thyroid hormone poisoning: Template:Multicol

- Palpitations

- Tachycardia (rapid heart rate: 100-120 beats per minute, or higher)

- Arrhythmia (irregular heart beat)

- Hypertension (Raised blood pressure)

- Tremor (usually fine shaking, e.g., hands)

- Hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating)

- Heat intolerance

- Polyphagia (increased appetite)

- Unexplained weight loss despite increased appetite

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath)

- Muscle weakness (especially in the large muscles of the arms and legs) and degeneration

- Diminished/changed sex drive

- Insomnia (inability to get enough sleep)

- Increased energy

- Fatigue

- Mental impairment, memory lapses, diminished attention span

- Decreased concentration

- Nervousness, agitation

- Irritability

- Restlessness

- Erratic behavior

- Emotional lability

- Brittle nails

- Abnormal breast enlargement

- Goiter (enlarged thyroid gland)

- Protruding eyeballs

- Diplopia (double vision)

- Eye pain, irritation, tingling sensation behind the eyes or the feeling of grit or sand in the eyes

- Swelling or redness of eyes or eyelids/eyelid retraction

- Sensitivity to light

- Decrease in menstrual periods (oligomenorrhea), irregular and scant menstrual flow (amenorrhea)

- Difficulty conceiving/infertility/recurrent miscarriage

- Chronic sinus infections

- Lumpy, reddish skin of the lower legs (pretibial myxedema)

- Increased bowel movements or diarrhea

- Panic attacks

Incidence and epidemiology

The disease occurs most frequently in women (7:1 compared to men). It occurs most often in middle age (most commonly in the third to fifth decades of life), but is not uncommon in adolescents, during pregnancy, during menopause, or in people over age 50. There is a marked family preponderance, which has led to speculation that there may be a genetic component. To date, no clear genetic defect has been found that would point at a monogenic cause.

Pathophysiology

Graves' disease is an autoimmune disorder, in which the body produces antibodies to the receptor for thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). (Antibodies to thyroglobulin and to the thyroid hormones T3 and T4 may also be produced.)

These antibodies cause hyperthyroidism because they bind to the TSH receptor and chronically stimulate it. The TSH receptor is expressed on the follicular cells of the thyroid gland (the cells that produce thyroid hormone), and the result of chronic stimulation is an abnormally high production of T3 and T4. This in turn causes the clinical symptoms of hyperthyroidism, and the enlargement of the thyroid gland visible as goiter.

The infiltrative exophthalmos that is frequently encountered has been explained by postulating that the thyroid gland and the extraocular muscles share a common antigen which is recognized by the antibodies. Antibodies binding to the extraocular muscles would cause swelling behind the eyeball.

The "orange peel" skin has been explained by the infiltration of antibodies under the skin, causing an inflammatory reaction and subsequent fibrous plaques.

There are 3 types of autoantibodies to the TSH receptor currently recognized:

- TSI, Thyroid stimulating immunoglobulins: these antibodies (mainly IgG) act as LATS (Long Acting Thyroid Stimulants), activating the cells in a longer and slower way than TSH, leading to an elevated production of thyroid hormone.

- TGI, Thyroid growth immunoglobulins: these antibodies bind directly to the TSH receptor and have been implicated in the growth of thyroid follicles.

- TBII, Thyrotrophin Binding-Inhibiting Immunoglobulins: these antibodies inhibit the normal union of TSH with its receptor. Some will actually act as if TSH itself is binding to its receptor, thus inducing thyroid function. Other types may not stimulate the thyroid gland, but will prevent TSI and TSH from binding to and stimulating the receptor.

Etiology

The trigger for auto-antibody production is not known. There appears to be a genetic predisposition for Graves' disease, suggesting that some people are more prone than others to develop TSH receptor activating antibodies due to a genetic cause. HLA DR (especially DR3) appears to play a significant role.[21]

Since Graves' disease is an autoimmune disease which appears suddenly, often quite late in life, it is thought that a viral or bacterial infection may trigger antibodies which cross-react with the human TSH receptor (a phenomenon known as antigenic mimicry, also seen in some cases of type I diabetes).

One possible culprit is the bacterium Yersinia enterocolitica (a cousin of Yersinia pestis, the agent of bubonic plague). However, although there is indirect evidence for the structural similarity between the bacteria and the human thyrotropin receptor, direct causative evidence is limited.[21] Yersinia seems not to be a major cause of this disease, although it may contribute to the development of thyroid autoimmunity arising for other reasons in genetically susceptible individuals.[22] It has also been suggested that Y. enterocolitica infection is not the cause of auto-immune thyroid disease, but rather is only an associated condition; with both having a shared inherited susceptibility.[23] More recently the role for Y. enterocolitica has been disputed.[24]

Treatment

Treatment of Graves' disease includes antithyroid drugs which reduce the production of thyroid hormone, radioiodine (radioactive iodine I-131), and thyroidectomy (surgical excision of the gland). As operating on a frankly hyperthyroid patient is dangerous, prior to thyroidectomy preoperative treatment with antithyroid drugs is given to render the patient "euthyroid" (i.e. normothyroid).

Treatment with antithyroid medications must be given for six months to two years, in order to be effective. Even then, upon cessation of the drugs, the hyperthyroid state may recur. Side effects of the antithyroid medications include a potentially fatal reduction in the level of white blood cells. Therapy with radioiodine is the most common treatment in the United States, whilst antithyroid drugs and/or thyroidectomy is used more often in Europe, Japan, and most of the rest of the world.

Antithyroid drugs

The main antithyroid drugs are carbimazole (UK), methimazole (US), and propylthiouracil (PTU). These drugs block the binding of iodine and coupling of iodotyrosines. The most dangerous side-effect is agranulocytosis (1/250, more in PTU); this is an idiosyncratic reaction which does not stop on cessation of drug. Others include granulocytopenia (dose dependent, which improves on cessation of the drug) and aplastic anemia. Patients on these medications should see a doctor if they develop sore throat or fever. The most common side effects are rash and peripheral neuritis. These drugs also cross the placenta and are secreted in breast milk. Lygole is used to block hormone synthesis before surgery.,

A randomized control trial testing single dose treatment for Graves found methimazole achieved euthyroid state more effectively after 12 weeks than did propylthyouracil (77.1% on methimazole 15 mg vs 19.4% in the propylthiouracil 150 mg groups).[25]

A study has shown no difference in outcome for adding thyroxine to antithyroid medication and continuing thyroxine versus placebo after antithyroid medication withdrawal. However two markers were found that can help predict the risk of recurrence. These two markers are a positive Thyroid Stimulating Hormone receptor antibody (TSHR-Ab) and smoking. A positive TSHR-Ab at the end of antithyroid drug treatment increases the risk of recurrence to 90% (sensitivity 39%, specificity 98%), a negative TSHR-Ab at the end of antithyroid drug treatment is associated with a 78% chance of remaining in remission. Smoking was shown to have an impact independent to a positive TSHR-Ab.[26]

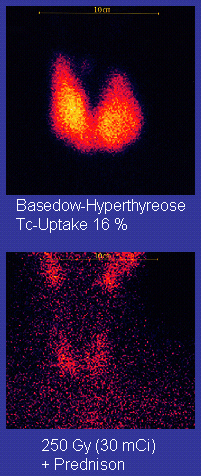

Radioiodine

Radioiodine (radioactive iodine-131) was developed in the early 1940s at the Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center. This modality is suitable for most patients, although some prefer to use it mainly for older patients. Indications for radioiodine are: failed medical therapy or surgery and where medical or surgical therapy are contraindicated. Hypothyroidism may be a complication of this therapy, but may be treated with thyroid hormones if it appears. Patients who receive the therapy must be monitored regularly with thyroid blood tests to ensure that they are treated with thyroid hormone before they become symptomatically hypothyroid. For some patients, finding the correct thyroid replacement hormone and the correct dosage may take many years and may be in itself a much more difficult task than is commonly understood.

Contraindications to RAI are pregnancy (absolute), ophthalmopathy (relative; it can aggravate thyroid eye disease), solitary nodules.

Disadvantages of this treatment are a high incidence of hypothyroidism (up to 80%) requiring eventual thyroid hormone supplementation in the form of a daily pill(s). The radio-iodine treatment acts slowly (over months to years) to destroy the thyroid gland, and Graves disease-associated hyperthyroidism is not cured in all persons by radioiodine, but has a relapse rate that depends on the dose of radioiodine which is administered.

Surgery

This modality is suitable for young patients and pregnant patients. Indications are: a large goiter (especially when compressing the trachea), suspicious nodules or suspected cancer (to pathologically examine the thyroid) and patients with ophthalmopathy.

Both bilateral subtotal thyroidectomy and the Hartley-Dunhill procedure (hemithyroidectomy on 1 side and partial lobectomy on other side) are possible.

Advantages are: immediate cure and potential removal of carcinoma. Its risks are injury of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, hypoparathyroidism (due to removal of the parathyroid glands), hematoma (which can be life-threatening if it compresses the trachea) and scarring.

No treatment

If left untreated, more serious complications could result, including birth defects in pregnancy, increased risk of a miscarriage, and in extreme cases, death. Graves-Basedow disease is often accompanied by an increase in heart rate, which may lead to further heart complications including loss of the normal heart rhythm (atrial fibrillation), which may lead to stroke. If the eyes are proptotic (bulging) severely enough that the lids do not close completely at night, severe dryness will occur with a very high risk of a secondary corneal infection which could lead to blindness. Pressure on the optic nerve behind the globe can lead to visual field defects and vision loss as well.

Symptomatic treatment

β-blockers (such as propranolol) may be used to inhibit the sympathetic nervous system symptoms of tachycardia and nausea until such time as antithyroid treatments start to take effect.

Treatment of eye disease

Mild cases are treated with lubricant eye drops or non steroidal antiinflammatory drops. Severe cases threatening vision (Corneal exposure or Optic Nerve compression) are treated with steroids or orbital decompression. In all cases cessation of smoking is essential. Double vision can be corrected with prism glasses and surgery (the latter only when the process has been stable for a while).

Notable sufferers

- John Adams (assumed), second President of the United States [27]

- Ayaka, Japanese singer/songwriter[28]

- Toni Childs, American singer/songwriter[29]

- Gail Devers, Athletic champion[30]

- Bobby Engram, NFL Wide Receiver[citation needed]

- Marty Feldman, British comedian[31]

- Diane Finley, Canadian cabinet minister[32]

- Ron Hornaday, NASCAR Driver[citation needed]

- Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin's wife[citation needed]

- Yūko Miyamura, Japanese voice actress[33]

- Cecil Spring-Rice, British Ambassador to the USA from 1912 to 1918[34]

Notes

- ^ Brent GA. Clinical practice. Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jun 12;358(24):2594-605.

- ^ Mathew Graves at Who Named It?

- ^ Graves, RJ. New observed affection of the thyroid gland in females. (Clinical lectures.) London Medical and Surgical Journal (Renshaw), 1835; 7: 516-517. Reprinted in Medical Classics, 1940;5:33-36.

- ^ Von Basedow, KA. Exophthalmus durch Hypertrophie des Zellgewebes in der Augenhöhle. [Casper's] Wochenschrift für die gesammte Heilkunde, Berlin, 1840, 6: 197-204; 220-228. Partial English translation in: Ralph Hermon Major (1884-1970): Classic Descriptions of Disease. Springfield, C. C. Thomas, 1932. 2nd edition, 1939; 3rd edition, 1945.

- ^ Von Basedow, KA. Die Glotzaugen. [Casper's] Wochenschrift für die gesammte Heilkunde, Berlin, 1848: 769-777.

- ^ a b c d e f g Basedow's syndrome or disease at Who Named It? - the history and naming of the disease

- ^ a b c d Robinson, Victor, ed. (1939). "Exophthalmic goiter, Basedow's disease, Grave's disesase". The Modern Home Physician, A New Encyclopedia of Medical Knowledge. WM. H. Wise & Company (New York)., pages 82, 294, and 295.

- ^ Goiter, Diffuse Toxic at eMedicine

- ^ Flajani, G. Sopra un tumor freddo nell'anterior parte del collo broncocele. (Osservazione LXVII). In Collezione d'osservazioni e reflessioni di chirurgia. Rome, Michele A Ripa Presso Lino Contedini, 1802;3:270-273.

- ^ Testa, AG. Delle malattie del cuore, loro cagioni, specie, segni e cura. Bologna, 1810. 2nd edition in 3 volumes, Florence, 1823; Milano 1831; German translation, Halle, 1813.

- ^ Giuseppe Flajina at Who Named It?

- ^ Parry, CH. Enlargement of the thyroid gland in connection with enlargement or palpitations of the heart. Posthumous, in: Collections from the unpublished medical writings of C. H. Parry. London, 1825, pp. 111-129. According to Garrison, Parry first noted the condition in 1786. He briefly reported it in his Elements of Pathology and Therapeutics, 1815. Reprinted in Medical Classics, 1940, 5: 8-30.

- ^ Hull G (1998). "Caleb Hillier Parry 1755-1822: a notable provincial physician". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 91 (6): 335–8. PMC 1296785. PMID 9771526.

- ^ Caleb Hillier Parry at Who Named It?

- ^ Sayyid Ismail Al-Jurjani. Thesaurus of the Shah of Khwarazm.

- ^ Ljunggren JG (1983). "[Who was the man behind the syndrome: Ismail al-Jurjani, Testa, Flajina, Parry, Graves or Basedow? Use the term hyperthyreosis instead]". Lakartidningen. 80 (32–33): 2902. PMID 6355710.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nabipour, I. (2003), "Clinical Endocrinology in the Islamic Civilization in Iran", International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 1: 43–45 [45]

- ^ Wallaschofski H, Kuwert T, Lohmann T (2004). "TSH-receptor autoantibodies - differentiation of hyperthyroidism between Graves' disease and toxic multinodular goiter". Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 112 (4): 171–4. doi:10.1055/s-2004-817930. PMID 15127319.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. - Thyroid - 17(10):1013". Liebertonline.com. doi:10.1089/thy.2007.0185. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ^ Cawood T, Moriarty P, O'Shea D (2004). "Recent developments in thyroid eye disease". BMJ. 329 (7462): 385–90. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7462.385. PMC 509348. PMID 15310608.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Tomer Y, Davies T (1993). "Infection, thyroid disease, and autoimmunity" (PDF). Endocr Rev. 14 (1): 107–20. doi:10.1210/er.14.1.107. PMID 8491150.

- ^ Toivanen P, Toivanen A (1994). "Does Yersinia induce autoimmunity?". Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 104 (2): 107–11. PMID 8199453.

- ^ Strieder T, Wenzel B, Prummel M, Tijssen J, Wiersinga W (2003). "Increased prevalence of antibodies to enteropathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica virulence proteins in relatives of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease". Clin Exp Immunol. 132 (2): 278–82. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02139.x. PMID 12699417.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hansen P, Wenzel B, Brix T, Hegedüs L (2006). "Yersinia enterocolitica infection does not confer an increased risk of thyroid antibodies: evidence from a Danish twin study". Clin Exp Immunol. 146 (1): 32–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03183.x. PMID 16968395.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Homsanit M, Sriussadaporn S, Vannasaeng S, Peerapatdit T, Nitiyanant W, Vichayanrat A (2001). "Efficacy of single daily dosage of methimazole vs. propylthiouracil in the induction of euthyroidism". Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 54 (3): 385–90. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01239.x. PMID 11298092.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Glinoer D, de Nayer P, Bex M (2001). "Effects of l-thyroxine administration, TSH-receptor antibodies and smoking on the risk of recurrence in Graves' hyperthyroidism treated with antithyroid drugs: a double-blind prospective randomized study". Eur. J. Endocrinol. 144 (5): 475–83. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1440475. PMID 11331213.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/5132/John-Adams/128/Foreign-service

- ^ "Hiro Mizushima, Ayaka married since February". Tokyograph. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ^ "Toni Childs' comes back from the 'Graves' - ABC Adelaide (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. 2008-10-01. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ^ "A Champion Battles Thyroid Disease: Gail Devers' Story". Wrongdiagnosis.healthology.com. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ^ Kugler, R.N., Mary (December 9, 2003). "Graves' Disease and Research: Multiple Areas of Study". About.com. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ^ Gombu, Phinjo (January 5, 2007). "Immigration file a revolving door". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ Miyamura, Yuko (September 10, 2007). "Blog Entry" (in Japanese). Yuko Miyamura blog. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ Burton, David H. (1990). Cecil Spring Rice: A Diplomat's Life. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0838633951.

See also

- Autoimmune disease

- Autoimmunity

- Chronic illness

- Disease management (health)

- Doctor-patient relationship

- E-Patient

- Thyroid disease health scam

- Thyrotropin-releasing hormone

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- Thyroid hormone

- Thyroxine (T4)

- Triiodothyronine (T3)

- Calcitonin

- Goitrogen

- Thioamide (e.g. PTU)

- Levothyroxine (e.g. Synthroid)

- Desiccated thyroid extract

- Iodine-131

- Thyroidectomy

External links

Comprehensive Resources

- Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia entry for Graves' Disease: Information on causes, symptoms, treatments and complications

- Wrong Diagnosis entry for Graves' Disease: Extensive array of information on Graves' disease

- Graves' Disease Foundation

- Columbia University's New York Thyroid Center: Wide array of information on Thyroid dysfunction

- Endocrineweb entry about the Thyroid Gland

- Thyroid Disease Manager: Analysis of all aspects of human thyroid disease and thyroid physiology

- Thyroid portal at About.com: Managed by health activist and patient advocate Mary Shomon

- American Thyroid Association

- Thyroid Australia

Articles

- Thyroid Disease, Osteoporosis, and Calcium: Article about thyroid disease and the risk of osteoporosis from MedicineNet

- Drug Therapy: Antithyroid drugs: Newsletter article from Medicina Interna

- Patient information: Antithyroid drugs at UpToDate

This template is no longer used; please see Template:Endocrine pathology for a suitable replacement