Raging Bull

| Raging Bull | |

|---|---|

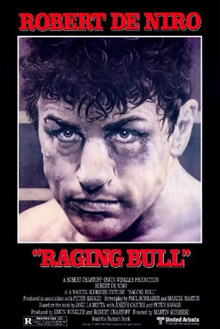

theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Written by | Screenplay: Paul Schrader Mardik Martin Martin Scorsese (uncredited) Robert De Niro (uncredited) Book: Jake LaMotta Joseph Carter Peter Savage |

| Produced by | Robert Chartoff Irwin Winkler |

| Cinematography | Michael Chapman |

| Edited by | Thelma Schoonmaker |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates | United States: November 14, Template:Fy United Kingdom: February 19, Template:Fy |

Running time | 129 minutes |

| Country | Template:FilmUS |

| Language | Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. |

| Budget | $18,000,000 (est.) |

| Box office | $23,383,987 |

Raging Bull is a 1980 American biographical film directed by Martin Scorsese, adapted by Paul Schrader and Mardik Martin from the memoir Raging Bull: My Story. It stars Robert De Niro as Jake LaMotta, a middleweight boxer whose sadomasochistic rage, sexual jealousy, and animalistic appetite exceeded the boundaries of the prizefight ring, and destroyed his relationship with his wife and family. Also featured in the film are Joe Pesci as Joey, La Motta's well intentioned brother and manager who tries to help Jake battle his inner demons, and Cathy Moriarty as his abused teen-aged wife. The film features supporting roles from Nicholas Colasanto, Theresa Saldana, and Frank Vincent, who has starred in many films directed by Martin Scorsese.

After receiving mixed initial reviews, (and criticism due to its disturbing level of violence, and upsetting material) it went on to garner a high critical reputation and is now widely regarded among the greatest movies ever made, along with Scorsese and De Niro's other famed collaboration from that era, Taxi Driver (1976).[citation needed] It is one of five films that has been named to the National Film Registry in its first year of eligibility, (along with Do the Right Thing, Goodfellas, Toy Story, and Fargo.)

Plot

Beginning in 1964, where an older and fatter Jake LaMotta (Robert De Niro) practices his stand-up comic routine, a flashback shifts to his boxing career in New York of 1941 against his opponent, Jimmy Reeves, in the infamous Cleveland bout. Losing the fight by a fixed result causes a fight to break out at the end of the match.[1] His brother Joey LaMotta (Joe Pesci) is not only a sparring partner to him but also responsible for organizing his fights. Joey discusses a potential shot for the title with one of his mob connections, Salvy Batts (Frank Vincent), on the way to his brother's house in their neighborhood in the Bronx. When they are finally settled in the house, Jake admits that he does not have much faith in his own abilities.[1] Accompanied by his brother to the local open-air swimming pool, a restless Jake spots a 15-year-old girl named Vickie at the edge of the pool (Cathy Moriarty). Although he has to be reminded by his brother he is already married, the opportunity to invite her out for the day very soon comes true when Joey gives in.[1]

Jake has two fights with Sugar Ray Robinson, set two years apart, and Jake loses the second when the judges rule in favor of Sugar Ray because he was leaving the sport temporarily for conscription in the United States Army.[1] This does not deter Jake from winning six straight fights, but as his fears grow about his wife, Vickie, having feelings for other men, particularly Tony Janiro, the opponent for his forthcoming fight, he is keen enough to show off his sexual jealousy when he beats him in front of the local Mob boss, Tommy Como (Nicholas Colosanto) and Vickie.[1] The recent triumph over Janiro is touted as a major boost for the belt as Joey discusses this with journalists, though Joey is briefly distracted by seeing Vickie approach a table with Salvy and his crew. Joey has a word with Vickie, who says she is giving up on his brother. Blaming Salvy, Joey viciously attacks him in a fight that spills outside of the club.[2] When Tommy Como hears that the two of them rose fists in a public place, he orders them to apologize and tells Joey that he means business. At the swimming pool, Joey tells Jake that if he really wants a shot, he will have to take a dive first.[2] In the fight against Billy Fox, Jake does not even bother to put up a fight. Jake is suspended from the board on suspicion of throwing the fight, though he realizes the error of his judgment when it is too late.[2] This does little to harm his career, when he finally wins the title against Marcel Cerdan at the open air Briggs Stadium.

Three years pass and Jake asks his brother if he fought with Salvy at the Copa because of Vickie. Jake then asks if Joey had an affair with his wife. Joey refuses to answer and decides to leave. Jake decides to find the truth for himself, interrogating his wife about the affair when she sarcastically states that she had sex with the entire neighborhood (including his brother, Salvy, and Tommy Como) and "sucked his brothers cock" after he knocks down the bathroom door where his wife is briefly hiding from him. Running straight towards his brother's house, he starts a fight with Joey.[2] Defending his championship belt against Laurent Dauthuille, he makes a call to his brother after the fight, but when Joey assumes Salvy is on the other end, Jake says nothing. This drags Jake down to when he eventually loses to Sugar Ray Robinson on their final (very violent) encounter, letting Sugar Ray land several hard blows on him as punishment for what he did.[2]

A couple of years later, in the middle of a photo shoot, Jake LaMotta surrounded by his wife and children, tells the journalists he is officially retired and that he has bought a new property. After staying all night at his new nightclub in Miami, Vickie tells him she wants a divorce, which she had been planning since his retirement. Further complicating things, Jake is charged as an accessory to a crime after introducing under-age girls (posing as 21-year-olds) to men. He ends up serving a jail sentence after failing to raise the bribe money by taking the jewels out of his championship belt instead of selling the belt itself.[2] In his cell, Jake brutally pounds the walls whilst sorrowfully questioning his misfortune, as he sits alone crying in despair. Returning to New York City, he meets up with his estranged brother Joey in a parking lot where they share a nervous hug.

Going back to the beginning sequence, the older Jake flatly recites the "I coulda' have been a contender" monologue from On the Waterfront. Darting across the room at the information of the crowded auditorium by the stage hand, the camera remains pivoted on the mirror as LaMotta chants 'I'm the boss' whilst shadowboxing. The film ends with Scorsese paying tribute to his former professor, Haig Manoogian, with a Biblical quote: "All I know is this: Once I was blind, and now I can see" symbolizing that even men like LaMotta can be redeemed. [2][3][4]

Cast

| Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Robert De Niro | Jake LaMotta[5] |

| Cathy Moriarty | Vickie Thailer LaMotta[5] |

| Joe Pesci | Joey LaMotta[5] |

| Frank Vincent | Salvy "Batts"[5] |

| Nicholas Colasanto | Tommy Como[5] |

| Theresa Saldana | Lenora LaMotta (Joey's wife)[5] |

| Mario Gallo | Mario[5] |

Development

Raging Bull came about when De Niro read the autobiography upon which the film is based on the set of 1900. Although disappointed by the poorly written style, he became fascinated by the character of Jake LaMotta when he showed the book to Martin Scorsese on the set of Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore as a means to hopefully consider the project.[6] Scorsese repeatedly turned down his offers by resisting the director's chair claiming he had no idea what Raging Bull was about, even though he did read some chapters of the text.[7] The book was then passed onto Mardick Martin, the film's eventual co-screenwriter who said "the trouble is the damn thing has been done a hundred times before - a fighter who has trouble with his brother and his wife and the mob is after him". The book was even shown to producer Irwin Winkler by De Niro, who was all too happy to do this only if Scorsese agreed.[8] A near-death experience from a drug overdose caused Scorsese to agree to make the film for the sake of De Niro, not only to save his own life but also to save what remained of his career. Scorsese knew that he could relate to the story of Jake LaMotta as a way to redeem himself when he saw the role being portrayed as an everyman that "...the ring becomes an allegory of life" making the project a very personal one to him.[9][10][11][12]

Preparation for the film began with Scorsese shooting some 8mm color footage featuring De Niro boxing in a ring. One night when the footage was being shown to De Niro, Michael Chapman, and his friend and mentor, the English director Michael Powell, Powell pointed out that color of the gloves at the time would have only been maroon, oxblood, or even black. Scorsese decided to use this as one of the reasons to film Raging Bull in black and white. Other reasons would be to distinguish the film from other color films around the time and to acknowledge the problem of fading color film stock - an issue Scorsese recognized.[13][14][15] Scorsese even went to two matches at the Madison Square Garden to aid his research, picking up on minor but essential details such as the blood sponge and latterly, the blood on the ropes (which would later be used in the film).[15]

Screenplay

Under the guidance of Winkler, Mardik Martin was asked to start writing the screenplay.[16] According to De Niro, under no circumstances would United Artists accept Mardik Martin's script.[17] The story which was based around the vision of journalist, Peter Hamill of a 1930s and 1940s style when boxing was known as "the great dark prince of sports" did not impress the expectations of De Niro very much when he finished reading the first draft.[18] Taxi Driver screenwriter Paul Schrader was swiftly brought in to re-write the script around August 1978.[18] Some of the changes that Schrader made to the script saw a re-write of the scene with the uncooked steak and inclusion of LaMotta seen urinating in a Florida cell. The character of Jake's brother, Joey was finally added, previously absent from Martin's script.[18][17] United Artists saw a massive improvement on the quality of the script. However, its chief executives, Steve Bach and David Field, met up with Scorsese, De Niro, and producer, Irwin Winkler in November 1978 to say they were worried that the content would be X-rated material and have no chance of finding an audience.[13] According to Scorsese, the script was left in the hands of him and De Niro where they spent two and a half weeks extensively re-building the content of the film which was done on the island of Saint Martin.[12] The most significant change would be the entire scene when Jake fixes his television and then accuses his wife of having an affair. Other changes included the removal of Jake and Joey's father; the reduction of the organized mob and a major re-write of Jake's fight with Tony Janiro.[19][20] They were even responsible for the end sequence where Jake is all alone in his dressing room quoting the I shouda been a contender scene from On the Waterfront to blame his brother and also himself.[20] An extract of Richard III had been pondered but Michael Powell thought it would be a bad decision within the context of a film that was American.[12] According to Steven Bach, only the first two screenwriters (Mardick Martin and Paul Schrader) would receive credit but since there was no payment to the writer's guild on the script, De Niro and Scorsese's work would remain uncredited.[20]

Casting

A trademark of Martin Scorsese was casting many actors and actresses new to the profession, which on this occasion there would be no exception.[21] Robert De Niro, who was already committed to play Jake LaMotta, began to help Scorsese track down unfamiliar names to play his on-screen brother, Joey, and wife, Vikki.[22][23] The role of Joey LaMotta was the first to be cast. Robert De Niro was watching a low budget television film called The Death Collector when he saw the part of a young career criminal played by Joe Pesci (then an unknown and struggling actor) as an ideal candidate. Prior to receiving a call from De Niro and Scorsese for the proposal to star in the film, Pesci had not worked in film for four years and was now running an Italian restaurant in New Jersey. Pesci initially claimed that it would have to be a good role for him to consider it, and he later accepted the part. The role of Vickie LaMotta, Jake's wife, would have much interest across the board, but it was Pesci who suggested the actress, Cathy Moriarty, from a picture he once saw at a New Jersey disco.[23] Both De Niro and Scorsese believed that Moriarty could portray the role after meeting with her on several occasions and noticing her husky voice and maturity. The duo had to prove to the Screen Actors Guild that she was right for the role when Cis Corman showed 10 comparing pictures of both Cathy Moriarty and the real Vickie LaMotta for proof she had a resemblance.[23] Moriarty was then asked to take a screen test which she managed—partly aided with some improvised lines from De Niro—after some confusion wondering why the crew were filming her take. Joe Pesci also persuaded his former show-biz pal and co-star in The Death Collector, Frank Vincent to try for the role of Salvy Batts. Following a successful audition and screen test, Vincent received the call to say he had received the part.[24] Charles Scorsese, the director's father, made his film debut as Tommy Como's cousin, Charlie.[24]

While in the midst of practicing a Bronx accent and preparing for his role, De Niro met both Jake LaMotta and his ex-wife, Vikki LaMotta on separate occasions. Vickie who lived in Florida would tell stories about her life with her former husband and also show old home movies (that would later inspire a similar sequence to be done for the film).[25][14] Jake LaMotta, on the other hand, would serve as his trainer accompanied by Al Silvani as coach at the Gramercy club in New York getting him into shape. The actor found that boxing came naturally to him; he entered as a middleweight boxer, winning two of his three fights in a Brooklyn ring dubbed "young LaMotta" by the commentator. According to Jake LaMotta, he felt that De Niro was one of his top 20 best middleweight boxers of all time.[14][23]

Principal photography

The film began shooting at a Los Angeles warehouse in April 1979.[26][23] The warehouse was modified to replicate the Madison Square Garden venue in New York as the site of the boxing scenes.[23] Scorsese made it clear during filming that he did not appreciate the traditional way in films to show fights from the spectators' view.[15] He insisted that one camera operated by the Director of Photography, Michael Chapman would be placed inside the ring as he would play the role of an opponent keeping out of the way of other fighters so that we could see the emotions of the fighters, including those of Jake.[23] The precise moves of the boxers would be done as dance routines from the information of a book about dance instructors in the mode of Arthur Murray. A punching bag which sat in the middle of the ring was used by De Niro between takes before aggressively coming straight on to do the next scene.[23][27] The initial five-week schedule for the shooting of the boxing scenes took longer than expected, putting Scorsese under pressure.[23] According to Scorsese, production of the film was then closed down for around four months with the entire crew was being paid, so De Niro could go on a binge eating trip around Northern Italy and France.[14][27] When he did come back to the United States, his weight increased from 145 to 215 pounds (66 to 97 kg).[23] The scenes with the fatter Jake LaMotta—which include announcing his retirement from boxing and LaMotta ending up in a Florida cell—were completed while approaching Christmas 1979 within seven to eight weeks so as not to aggravate the health issues which were already affecting De Niro's posture, breathing, and talking.[27][23][28] The final sequence where Jake LaMotta is sitting in front of his mirror was filmed on the last day of shooting taking nineteen takes with only the thirteenth one being used for the film. Scorsese wanted to have an atmosphere that would be so cold that the words would have an impact as he tries to come to terms with his relationship with his brother as well as himself.[12]

Post-production

The editing of Raging Bull began when production was temporarily put on hold and was completed in 1980.[29][27] Scorsese worked with the editor, Thelma Schoonmaker to achieve a final cut of the film. Their main decision was to ditch Schrader's idea of LaMotta's nightclub act intervening with the flashback of his youth and instead just follow along the lines of a single flashback where only scenes of LaMotta practicing his stand-up would be left "bookending" the film.[30] A sound mix arranged by Frank Warner was a delicate process taking six months.[29] According to Scorsese, the sound on Raging Bull was difficult because each punch, camera shot, and flash bulb would be different. Also, there was the issue of trying to balance the quality between scenes featuring dialogue and those involving boxing (which were done in Dolby).[27] Raging Bull went through a test screening in front of a small audience including the chief executives of United Artists, Steve Bach and Arthur Alberk. The screening was shown at the MGM screening room in New York around July 1980. Later, Alberk praised Scorsese by calling him a "true artist".[29] According to the producer, Irwin Winkler, matters were made worse when United Artists decided not to distribute the film but no other studios were interested when they attempted to sell the rights.[29] Scorsese made no secret that Raging Bull would be his "Hollywood swan song" and he took unusual care of its rights during post-production.[9] This caused some friction with Irwin Winkler, who accused Scorsese of doing the editing process "inch by inch". Scorsese threatened to remove his credit from the film if he was not allowed to sort a reel which obscured the name of a whiskey brand known as "Cutty Sark" which was heard in a scene. The work was only completed four days shy of the premiere.[31]

Reception

Distribution

Raging Bull first premiered in New York on November 14, 1980 to mixed reviews.[29][32] Jack Kroll of Newsweek called Raging Bull "the best movie of the year"[29] Vincent Canby of The New York Times said that Scorsese "has made his most ambitious film as well as his finest" and went on to praise Moriarty's debut performance as "either she is one of the film finds of the decade or Mr. Scorsese is svengali. Perhaps both."[33] Time praised De Niro's performance since "much of Raging Bull exists because of the possibilities it offers De Niro to display his own explosive art".[33] Steven Jenkins from the British Film Institute's (BFI) magazine, Monthly Film Journal said "Raging Bull may prove to be Scorsese's finest achievement to date".[33] Many critics however were repelled by the film's violence and its unsympathetic central character. For example, Kathleen Carroll from the The New York Times criticized the character of Jake LaMotta as "one of the most repugnant characters in the history of the movies" who also criticized Scorsese because the movie "totally ignores [LaMotta's] reform school background, offering no explanation to his anti-social behavior".[29]

The unsettling brew of violence and anger, combined with the lack of a proper advertising campaign, led to the film having a modest box office intake of $23 million. Scorsese became concerned for his future career and worried that producers and studios might refuse to finance his films.[33] According to Box Office Mojo, the film grossed $23,383,987 in domestic theaters.[34]

Awards

Raging Bull was nominated for eight Academy Awards (including Best Picture, Director, Actor, Supporting Actress, Supporting Actor, Cinematography, Sound, and Editing) at the 1980 Academy Awards.[33][35] However, when it was revealed that John Hinckley, Jr.'s assassination attempt of the then president Ronald Reagan had been influenced by his love for Taxi Driver, this hurt the chances for the film to pick up the Oscar.[33] Out of fear of being attacked, Scorsese went to the ceremony with FBI bodyguards disguised as guests who escorted him out before the announcement of the Academy Award for Best Picture was made - the winner being Ordinary People. Nevertheless, the film managed to pick up two awards including Best Actor (De Niro) and Best Editing (Schoonmaker).[33]

The Los Angeles Film Association voted Raging Bull the best film of 1980 and best actor for De Niro. The National Board of Review also voted best actor for De Niro and best supporting actor to Pesci. The Golden Globes awarded another best actor award for De Niro and National Society of Film Critics gave best cinematography to Chapman. The Berlin Film Festival chose Raging Bull to open the festival in 1981.[33]

Legacy

By the end of the 1980s, Raging Bull had cemented its reputation as a modern classic. It was voted the best film of the 1980s in numerous critics' polls and is regularly pointed to as both Scorsese's best film and one of the finest American movies ever made.[36] Several prominent critics, among them Roger Ebert, declared the film to be an instant classic and the consummation of Scorsese's earlier promise. Ebert proclaimed it the best film of the 1980s, and the fourth greatest film of all time.[37] The film has been deemed "culturally significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Raging Bull was fifth on the Entertainment Weekly's 100 Greatest Movies of All Time. The 2002 Sight and Sound Poll found listed tied for sixth with The Bicycle Thief.[38] In 2002, Channel 4 held a poll of the 100 Greatest Movies,on which Raging Bull was voted in at number 20. Halliwell Film Guide, a British film guide, placed Raging Bull' seventh in a poll naming their selection for the "Top 1,000 Movies". In 2008, Empire Magazine held a poll of the "500 Greatest Movies of All Time," taking votes from 10,000 readers, 150 film makers and 50 film critics: Raging Bull was placed at number 11.

American Film Institute recognition

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies #24

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills #51

- AFI's 10 Top 10 #1 Sports

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) #4

Soundtrack

Martin Scorsese decided to assemble a soundtrack made of music that was popular at the time using his personal collection of 78s. The songs were carefully chosen so they would be the ones that you would hear on the radio, at the pool or in bars and clubs reflecting the mood of that particular era.[39][40] Some lyrics from songs would be slipped into some dialogue. The Intermezzo from Cavalleria rusticana by Italian composer Pietro Mascagni would serve as the main theme to Raging Bull after a successful try-out by Scorsese and the editor, Thelma Schoonmaker over the film's opening titles.[40] Two other Mascagni pieces were used in the film: the Barcarolle from Silvano, and the Intermezzo from Guglielmo Ratcliff.[41] A two-CD soundtrack was released in 2005, long after the film was released, because of earlier difficulties receiving permissions for many of the songs, which Scorsese selected from his childhood memories growing up in New York.

Raging Bull II: Continuing the Story of Jake LaMotta

In 2006, Variety reported that Sunset Pictures was developing a sequel entitled Raging Bull II: Continuing the Story of Jake LaMotta. It still in the early stages of production and chronicles Jake's early life, as told in the sequel novel of the same name.[42] According to the Internet Movie Database, the film is to be directed by Martin Guigui and is rumored to star Mark Pellegrino as Jake LaMotta.

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull 2006 p.93-97, 98-103, 105.

- ^ a b c d e f g Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull 2006, p.106-107, 109-110, 112, 114, 116-121.

- ^ Friedman Lawrence S. Cinema of Martin Scorsese 1997, p.114.

- ^ Baxter, John DeNiro A Biography, p.184.

- ^ a b c d e f g Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull 2006 p.177.

- ^ Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls 1999, p.254.

- ^ Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls 1998, p.378.

- ^ Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls 1998, p.315.

- ^ a b Friedman Lawrence S. The Cinema of Martin Scorsese 1997, p.115.

- ^ Phil Villarreal. "Scorsese's 'Raging Bull' is still a knockout," The Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, AZ), February 11, 2005, page E1.

- ^ Kelly Jane Torrance. "Martin Scorsese: Telling stories through film," The Washington Times (Washington, DC), November 30, 2007, page E1.

- ^ a b c d Thompson, David and Christie, Ian Scorsese on Scorsese, pp.76/77.

- ^ a b Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls 1998, p.389.

- ^ a b c d Total Film The 100 greatest films of all time pp180-181

- ^ a b c Thompson, David and Christie, Ian Scorsese on Scorsese, p.80.

- ^ Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls 1998, p.379.

- ^ a b Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls pp384-385

- ^ a b c Baxter John DeNiro A Biography,pp.186-189.

- ^ Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls , p.390.

- ^ a b c Baxter, John DeNiro A Biography, p.193.

- ^ Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull, p.65.

- ^ Evans, John The Making of Raging Bull, p.61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Baxter, John DeNiro A Biography pp196-201

- ^ a b Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull, pp.65/66.

- ^ Baxter, John DeNiro A biography p.192.

- ^ Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls 1998, p.391/2.

- ^ a b c d e Thompson and Christie Scorsese on Scorsese pp83-84

- ^ Baxter, John The Making of Raging Bull, p.83.

- ^ a b c d e f g Biskind, Peter Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, p.399. Cite error: The named reference "Biskind p399" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull, p.90.

- ^ Baxter, John DeNiro A biography, p.204.

- ^ Baxter, Mike The Making of Raging Bull, p.90.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Evans, Mike The Making of Raging Bull pp124-129

- ^ "Raging Bull". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ "Raging Bull - Academy Awards Database". AMPAS. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

- ^ Walker, John Halliwell's Top 1000, The Ultimate Movie Countdown 2005, p.561.

- ^ Top Ten Lists of Roger Ebert

- ^ BFI | Sight & Sound | Top Ten Poll 2002 - Directors' Poll

- ^ Thompson, David and Christie, Ian Scorsese on Scorsese p.83.

- ^ a b Evans, David The Making of Raging Bull p.88.

- ^ "FAQ 9. What is that nice music in Raging Bull?". Mascagni.org. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Variety: Sunset Pictures in shape

Bibliography

- Thompson, Christie, David, Ian (1996). Scorsese on Scorsese.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Evans, Mike (2006). The Making of Raging Bull. London: Unanimous Ltd. ISBN 1903318831.

- Biskind, Peter (1998). Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. Bloomsbury.

- Baxter, John (2006). DeNiro A Biography.

External links

- Raging Bull at IMDb

- Raging Bull at the TCM Movie Database

- Raging Bull at AllMovie

- 1980 films

- 1980s drama films

- American drama films

- Biographical films

- Black and white films

- Boxing films

- English-language films

- Existentialist works

- Films based on biographies

- Films directed by Martin Scorsese

- Films featuring a Best Actor Academy Award winning performance

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films set in the 1960s

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Sports films based on actual events

- United States National Film Registry films