Richard Nixon 1968 presidential campaign

| Richard Nixon for President | |

|---|---|

| File:Nixon campaign logo.jpg | |

| Campaign | U.S. presidential election, 1968 |

| Candidate | Richard Nixon U.S. House of Representatives 1947-1950 U.S. Senator 1950–1953 Vice President 1953-1961 |

| Affiliation | Republican Party |

Former Vice President Richard Milhous Nixon of New York, launched a successful run for President of the United States in 1968, following a year of preparation, and five years of political reorganization following defeats in the 1960 Presidential election, and 1962 California Gubernatorial race.

En route to the Republican Party nomination, Nixon faced challenges from Michigan Governor George Romney, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and Governor Ronald Reagan of California. He won most of the state Primaries, and gained enough delegate strength to be victorious on the first ballot at the Republican National Convention. He named Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew as his running mate.

In the General election, "law and order" was a major theme of the Nixon campaign. He also attempted to de-emphasize the controversial Vietnam War, claiming to have a "secret plan" to end it. He ran well ahead of his opponent, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, in the polls, but began to slip after refusing to take part in presidential debates, and following the White House announcement of a bombing halt in Vietnam.

Nixon won in a close election on November 5, 1968, and was inaugurated as the 37th President of the United States on January 20, 1969.

Background

Nixon served as a member of the United States Congress representing the 12th District of California [1] from 1947 until his election to the Senate in 1950. During this time, he gained the reputation as an ardent anti-Communist. He was selected by Republican Party Presidential nominee Dwight D. Eisenhower as his running mate for the 1952 presidential election. After being elected, Nixon served as Vice President, and became known for his diplomatic skills. He was re-elected to the position in 1956. At the end of Eisenhower's second term in 1960, Nixon was nominated by the Republican Party as their presidential candidate. He lost in a close election to John F. Kennedy, which many credited to his "uncomfortable" disposition during the first televised debate.[2] After a defeat in the 1962 California Gubernatorial race, Nixon was labeled a "loser" by the media. [3] He moved to New York, joined a law firm, [4] regrouped and later began to plan for a second presidential run.

Campaign developments

Early stages

About a year before his campaign officially began, polls from early 1967 suggested that Nixon was the front-runner for the Republican nomination. A February Gallup poll showed him leading closest rival, Michigan governor George Romney, 52% to 40%. [5] In March, he gained the support of the 1964 Republican presidential nominee, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona. However, the Senator remarked that his party continued to believe that Nixon "can't be elected" due to his "loser" label. [6] That same month, a "Nixon for President Committee" was formed, [7] and headquarters for the organization opened in Washington in late May. [8]

During the spring and summer, Nixon went on international visits to locales including Eastern Europe [9] and Latin America [10] to display his foreign policy credentials. By August, he returned and held a secret meeting with his advisers on campaign strategy. Two days later, his campaign manager Gaylord Parkinson, left his position to be with his sick wife. Commentators opined that the vacancy built "an element of instability" for the campaign, but it was soon temporarily filled by former Governor Henry Bellmon of Oklahoma. [11] Following this, a number of changes were made at the Nixon headquarters. Five staff members were fired after private investigators determined that information had been leaked to the campaigns of potential candidates Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York and Governor Ronald Reagan of California.[12]

By mid-September 1967, Nixon organized campaign headquarters in four states deemed critical to the Republican Party primaries. He hoped the moves would increase his delegate strength and demonstrate his "the ability to win." He also notified the media that a possible presidential run would be determined officially anytime between early December and February. [13] Plans for the handling of the war in Vietnam were discussed by Nixon and his staff at campaign headquarters. Nixon was advised to soften his stance on the war, and was encouraged to shift his focus from foreign affairs to domestic policy to avoid the divisive "war and peace" issue. Observers noted that this move could have hurt the candidate by turning away from his image "as a foreign policy expert." [14]

In October, political experts began to predict that Nixon would gain delegates in the important states of New Hampshire, Wisconsin and Nebraska during the primary season, starting in March 1968. They also noted that in the other critical state of Oregon, Ronald Reagan would be helped by the proximity of his home state. Like Nixon, rival George Romney began to set up an organization in these states to challenge for the nomination as well. [15] Romney officially announced his candidacy in November, prompting Nixon to step up his efforts. He spent most of this period on the trail in New Hampshire. Observers following Nixon, noted that during this period, he seemed more relaxed and easy-going than in his past political career. One commentator noted that he was not "the drawn, tired figure who debated Jack Kennedy or the angry politician who conceded his California (Gubernatorial) defeat with such ill grace." [16] He also began making appearances at fundraisers in his adopted home state of New York, helping to raise $300,000 for the senatorial campaign of Senator Jacob K. Javits. By the end of December, Nixon was described by Time Magazine as the "man to beat." [17]

Nixon entered the year 1968 as the front-runner for the Republican nomination. However, polls suggested that in a head to head match up with the incumbent President Lyndon Johnson, Nixon was behind in a 50% to 41% contest. [18] Later in the month, Nixon embarked on a tour of Texas. During a stop, he lampooned President Johnson's State of the Union address, asking "Can this nation afford to have four more years of Lyndon Johnson's policies that have failed at home and abroad?" At this time, reports suggested that Nixon would formally announce his bid in February. [19]

Primary campaign

On February 1 in New Hampshire, Nixon announced his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination, commenting that problems "beyond politics" needed to be addressed. [20] He campaigned in the state of New Hampshire, but polls suggested that he would easily win its primary. As a result, he began to also campaign in Wisconsin where the second primary would be held. During a stop, he briefly discussed Vietnam while not going into detail, stating that the United States "must prevent confrontations like that in Viet Nam" but that his nation "must help people in the free world fight against aggression, but not do their fighting for them." He used the dictatorships in Latin America as an example, stating: "I am talking not about marching feet but helping hands." [21] As military operations increased in Vietnam in mid-February, Nixon's standing against President Johnson improved. A Harris poll showed that the candidate trailed the president 43% to 48%. [22] Near the end of the month, Nixon's announced opponent George Romney exited the race, mostly due to comments he made about being "brainwashed" during a visit to Vietnam. The move left Nixon nearly unopposed for the upcoming primaries, and narrowed his presidential nomination opponents to Nelson Rockefeller and Ronald Reagan, neither of whom had announced their candidacy. [23]

Because of Romney's exit, Nixon remarked in early March that he would "greatly expand [his] efforts in the non-primary states." Time Magazine commented that Nixon could now focus his political attacks solely on President Johnson. However, the void also caused problems for Nixon. Time observed that the prospect of soundly defeating second tier candidate and former Governor of Minnesota Harold Stassen in the primaries, would not "electrify the voters." The Nixon campaign countered this claim stating that Romney's withdrawal was a "TKO" by Nixon. Meanwhile, Rockefeller was beginning to be viewed more as a candidate, articulating that he did not want to split the party but that he was "willing to serve...if called." [24] As talks of other candidates persisted, Nixon continued to campaign and discussed the issues. He made a "pledge" to end the war in Vietnam, but would not go into the details of his "secret" plan, which drew some criticism. [25] Nixon easily won the New Hampshire primary on March 12, pulling in 80% of the vote with a write-in campaign for Rockefeller receiving 11%. [26] At the end of March, Rockefeller announced that he would not campaign for the presidency, but would be open to being drafted. Nixon doubted a draft stating that it would only be likely if "I make some rather serious mistake." Reports suggested that the decision caused "Nixon's political stock [to] skyrocket." [27] Gallup polls showed that Nixon led President Johnson 41% to 39% in a three way race with American Independent Party candidate and former Governor George Wallace of Alabama included. [28]

As the Wisconsin Primary loomed in early April, Nixon's only obstacle seemed to be preventing his supporters from voting in the Democratic primary for Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota as a protest to President Johnson. However, Johnson withdrew from the race before the primary. Ronald Reagan's name was on the ballot in Wisconsin but he had never campaigned in the state and was still not a declared candidate. [29] Nixon won the primary with 80% followed by Reagan with 11% and Stassen with 6%. [30] But with Johnson removed from the race, Nixon fell behind Democratic candidates Eugene McCarthy, Hubert Humphrey and Robert Kennedy in head to head match-ups. [31] At the end of April, Nixon called for a moratorium on criticism of the Johnson policy in Vietnam as negotiations were underway. He also began to attack the Democratic candidates as opposed to Johnson, stating that "The one man who can do anything about peace is Lyndon Johnson, and I'm not going to do anything to undercut him" but that "A divided Democratic Party cannot unite a divided country; a united Republican Party can." [32] He also began to discuss economics more frequently, stating that spending needed to be cut, and criticized the Democratic plan of raising taxes instead. [33] During a question and answer session with the American Society of Newspaper Editors, Nixon spoke extemporaneously and received numerous interruptions of applause. The largest came when he addressed the issue of crime commenting that "there cannot be order in a free society without progress, and there cannot be progress without order." [34]

At the start of May, Rockefeller announced that he would campaign for the presidency, after all. Directly following his entrance, he defeated Nixon in the Massachusetts primary 30% to 26%. [35] New Harris polls found that Rockefeller was faring better against Democratic candidates than Nixon. [36] But the outlook started to look better for the former Vice President after he won the Indiana primary over Rockefeller. [37] Off the victory, Nixon campaigned in Nebraska where he criticized the three leading Democratic candidates as "three peas in a pod, prisoners of the policies of the past." He then proposed a plan to tackle crime that included wiretapping, legislation to counter previous Supreme Court decisions, the forming of a congressional committee targeting crime and reforms to the criminal justice system. He did not connect crime to racial rioting, drawing praise from Civil Rights leaders. [38] Nixon won the primary in Nebraska, defeating the non-candidate Reagan 71% to 22%. [39] At the next primary, in Oregon, Reagan seemed more willing to compete with Nixon, and Rockefeller sat out. [40] But Nixon won with 72%, fifty points ahead of Reagan. [41]

In early June, Nixon continued to be regarded as the favorite to win the nomination, but observers noted that he had not yet "locked up" the nomination as challenges were faced from Nelson Rockefeller and Ronald Reagan. Nixon was not on the ballot in California, where Reagan won a large slate of delegates. Behind the scenes, Nixon workers lobbied for delegates from "favorite son" candidates. [42] And as a result, Nixon received the backing of Senator Howard Baker of Tennessee, and the 28 delegates he had amassed, as well as the 58 delegates belonging to Senator Charles Percy of Illinois. [43] After the assassination of Robert Kennedy, like the other candidates, Nixon took a break from campaigning. [44] Reports suggested that the assassination all but assured his nomination. [45] Upon returning to the trail, Nixon found that Rockefeller began to attack him, describing the front-runner as a man "of the old politics" who has "great natural capacity not to do the right thing, especially under pressure." [44] Nixon refused to respond to the remarks, stating that he would not participate in attacks. [43] As Nixon edged closer to the nomination, discussions about his running mate arised. Republicans in the mid-west pushed for New York Mayor John Lindsay to be selected. [46] The endorsement of Nixon by Senator Mark Hatfield of Oregon raised speculation that he might be selected. [44] Congressman George Bush of Texas and Charles Percy were also mentioned as possible selections. [47] At the end of the month, Nixon had two thirds of the required 667 delegates necessary to win the nomination. [48]

On July 1, Nixon received the endorsement of Senator John G. Tower of Texas, handing him at least 40 delegates. [49] At this time, Nixon decided with a group of legislators that "crime and disorder" was the number one issue in the nation. This continued to be a major theme of the Nixon campaign, and would be using extensively during the general election. [50] He also announced his opposition to the military draft, stating that he would replace the current system with a volunteer army incentivized with higher pay. [51] Former President Dwight Eisenhower gave Nixon his endorsement in mid-July. Breaking his tradition of waiting until after the primary, Eisenhower stated that 1968 was an exceptional year because "the issues are so great and confusing."[52] By the end of July, reports circulated that Nixon had 691 probable delegates for the convention, placing him over the 667 delegate threshold. However, Rockefeller disputed these numbers. [53] Sources within Washington reported that Reagan was a cause of more concern for the Nixon campaign than Rockefeller. A possible scenario surfaced where Nixon's southern delegates would drop their support to back the more conservative Reagan. However, Nixon staffers believed that if such a scenario occurred, Rockefeller delegates in the Northeast would support Nixon to prevent a Reagan nomination. [54]

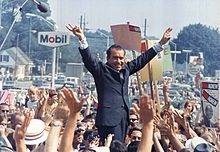

Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention was held from August 5 to 9 at the Miami Beach Convention Center in Miami Beach, Florida. At the convention, Richard Nixon was nominated for President on the first ballot with 692 delegates. Rockefeller finished in second with 277 delegates followed by Ronald Reagan, who had just entered the race, and compiled 182 delegates. [55] Nixon's early nomination occurred partly because he held on to delegates in the South. Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina and delegate Charlton Lyons of Louisiana were partly responsible for this hold. [56] After the nomination, Nixon held his hands in the air with two "v" signs of victory and delivered the acceptance speech he had been writing for two weeks. In the speech, he remarked: "Tonight I do not promise the millennium in the morning. I don't promise that we can eradicate poverty and end discrimination in the space of four or even eight years. But I do promise action. And a new policy for peace abroad, a new policy for peace and progress and justice at home." He called for a new era of negotiation with communist nations, a strengthening of the criminal justice system to fight crime, and marked himself as a champion of the American Dream. [57] Nixon also discussed economics, articulating his opposition to social welfare, and advocating programs designed to help African Americans start their own small businesses. By the end of the address, he promised that "the long dark night for America is about to end." [58] Following the speech, Nixon selected Governor Spiro Agnew of Maryland as his running mate. Agnew was relatively unknown nationally, but was selected in part because of his alleged appeal to African Americans. Agnew was thereafter nominated at the convention without much opposition. [59] Observers later noted that Nixon was the centrist candidate of the convention with Rockefeller to his left and Reagan to his right. The same analysis was made about the general campaign, with observers determining that Nixon would stand to the right of the still undecided Democratic nominee but would fall to the left of American Independent Party candidate George Wallace. [60]

General election

As the general election began, Nixon decided that he would focus his efforts on the "big seven" states of California, Texas, Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, Pennsylvania and New York. [61] He started this campaign with a tour of the mid-west. While on his first stop in Springfield, Illinois, he discussed the importance of unity, stating that "America [now] needs to be united more than any time since Lincoln." [62] He then traveled to Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania before returning to New York for a meeting with former rival Nelson Rockefeller. [59] In the latest Gallup polls following the convention, Nixon led Humphrey 45% to 29% and was ahead of McCarthy 42% to 37%. [63] At the end of the month, as Hubert Humphrey was narrowly selected over Eugene McCarthy as the Democratic presidential nominee at a protest filled convention, commentators opined that the split party and lack of "law and order," placed Nixon in good position. [64] Around this time, Nixon began regularly receiving briefings about the Vietnam War from President Johnson. [65] Johnson also explained to Nixon that he did not want the war to be politicized, and Nixon agreed but questioned whether Humphrey would also comply. [66]

Following the Democratic convention, Nixon continued to be labeled as the front-runner for the presidency, described in the media as "relaxed [and] confident," counter to his "unsure" self from 1960. Observers also wondered if even the Democratic President Johnson favored Nixon over Humphrey. [67] Nixon traveled to Chicago to campaign and was greeted by a large crowd, estimated at several hundred thousand. In the city, he used his campaign tactic of televised town hall meetings before a citizen panel, to speak to audiences throughout the state of Illinois. [68] Prior to his visit, he called upon Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, the highest ranking African American in the nation, to campaign with him on trips to Illinois and California. Nixon referred to Brooke as "one of my top advisers" while in Chicago and during a visit to San Francisco. Observers believed this was an attempt by Nixon to further gain favor with the African American community. [69] In mid-September, Nixon's running mate Spiro Agnew went on the offensive against Humphrey, acting in a role assigned by Nixon advisers. He referred to the Vice President as being "soft on Communism" as well as inflation and "law and order," and compared him to former British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. [70] At this time, Nixon sent advisor and former Governor of Pennsylvania William Scranton on an overseas fact finding trip to Europe to gain intelligence on the Western alliance and Soviet issues. In response to Humphrey's calls for a face to face debate, Nixon remarked: "Before we can have a debate between Nixon and Humphrey, Humphrey's got to settle his debate with himself." [71] Nixon campaigned in San Francisco, in front of 10,000 supporters amidst an array of protests. The candidate took on the protesters first hand, and delivered his "forgotten American" speech, declaring that election day would be "a day of protest for the forgotten American" which included those that "obey the law, pay their taxes, go to church, send their children to school, love their country and demand new leadership." [72] By the end of the month, many in the Nixon campaign believed his election was guaranteed and began to prepare for the transition period, despite Nixon's warning that "the one thing that can beat us now is overconfidence." [73] Gallup polls showed Nixon leading Humphrey 43% to 28% at the end of September. [74]

In early October, commentators weighed in on Nixon's advantage, explaining that he could legitimately blame the Johnson administration for the conflict in Vietnam, and use campaign advertisements with images of dead American soldiers while avoiding discussion about the war with the excuse that he did not want to disrupt the peace talks in Paris. [75] However, the candidate was heckled repeatedly on the campaign trail by anti-war protesters.[76] Nixon addressed the American Conservative Union on October 9, and argued that George Wallace's American Independent Party candidacy could split the anti-Administration vote, and help the Democrats. The Union decided to back Nixon over Wallace, labeling the third party candidate's beliefs as "Populist." [77] As Democratic Vice Presidential nominee Edmund Muskie criticized Nixon for his connections to Strom Thurmond, Nixon continued to oppose a possible debate with Humphrey and Wallace as well as a debate between the running mates, [78] on the basis that he did not want to give Wallace any more exposure. Observers noted that Nixon also was against debates due to his experience during the 1960 encounter with John F. Kennedy, which many cited as a factor in his defeat. [79] In another lesson learned from 1960, the campaign employed 100,000 workers to oversee Election day polling sites to prevent a reoccurrence of what many Republicans viewed as 1960's stolen election. [80] Nixon went on a train campaign tour of Ohio near the end of October. From the back of the "Nixon Victory Special" car, he bashed Vice President Humphrey as well as the Secretary of Agriculture and Attorney General of the Johnson cabinet, for farmer's debt and the rising crime rate. [81] By the end of October, Nixon was losing his edge over Humphrey, he led only 44% to 36% in Gallup polls down five points from a few weeks earlier, [82] observers noted that the decline was related to Nixon's refusal to debate. [83]

At the beginning of November, President Johnson announced that a bombing halt had been achieved in Vietnam. Observers noted that the development significantly helped Humphrey, although Nixon had given his support to the talks. [84] At this time, Nixon operative Anna Chennault secretly spoke with the South Vietnamese and explained that they could receive a better deal under Nixon. This charge, along with remarks from Nixon supporter and future Defense Secretary Melvin Laird that Johnson was deliberately misinforming Nixon, angered the President. He spoke with Nixon supporters, Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirkson and Senator George Smathers of Florida, who relayed to Nixon, Johnson's frustration. Two days before the election, Nixon went on Meet the Press and explained that he would cooperate completely with Johnson. He then phoned the President after the appearance and personally reassured him. [66] The final Harris poll before the election showed Nixon trailing Humphrey 43% to 40%, but Gallup's final poll showed Nixon leading 42% to 40%. [85] On the eve of the election, Nixon and Humphrey bought time on rival television networks to make their final pleas to the American people. Nixon appeared on NBC, while his Democratic challenger went on ABC. [86] Nixon used this appearance to counter the surge given to Humphrey by the bombing halt stating that he received "a very disturbing report" that tons of supplies were being moved into South Vietnam by the North. A charge that his opponent labeled as "irresponsible." [85]

Election Day

On November 5, Election Day, Nixon defeated Humphrey by a margin of 301 to 191 in the Electoral College, with 46 going to George Wallace. The popular vote was extremely close with Nixon edging Humphrey 43.42% to 42.72%, a margin of approximately 500,000 votes. Nixon won most of the West and mid-West but lost parts of the Northeast and Texas to Humphrey and lost the deep South to Wallace. [87]

Endorsements

|

List of people who endorsed Richard Nixon |

|---|

|

Aftermath

Nixon was sworn in as the 37th President of the United States on January 20, 1969. In his first term, he passed anti-crime legislation and nominated conservative judges to the bench. He also ended the military draft, and is credited with improving United States relations with China. He was re-elected in 1972, and thereafter brought an end to the American involvement in Vietnam. He was forced to resign the presidency in 1974, following the discovery of his role in the cover-up of the Watergate Scandal. Nixon retired from public life and served as an elder statesman until his death in 1994.[97]

References

- ^ "Election News Broadcast to 'Times' Readers", Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, California, November 6, 1946

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "A Politician". Nixonlibrary.gov. Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

- ^ "Kennedy In Speculation", The Free Lance-Star, Fredericksburg, Virginia, p. 3, March 13, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Devlin, James (May 2, 1963), "Nixon Plans to Change Residence to New York", The Free Lance-Star, Fredericksburg, Virginia, p. 1

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "In Business", Time Magazine, February 24, 1967

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Goldwater says he favors Nixon as candidate in '68", The Bulletin, Bend, Oregon, p. 1, March 29, 1967

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Hess, Steven; Broder, David (December 1, 1967), "The Political Durability Of Nixon", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 18

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Dick's Lucky Palm", Time Magazine, June 2, 1967

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Evans, Rowland; Novak, Robert (April 2, 1967), "Eastern Europeans Lobby Richard Nixon For Trade Measure", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 7

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nation: Around the World, A Block Away", Time Magazine, May 19, 1967

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Novak, Robert; Evans, Rowland (August 22, 1967), "Lack of Permanent Campaign Manager To Handicap Nixon", The Milwaukee Sentinel, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, p. 7

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Allen, Robert; Scott, Paul (September 1, 1967), "Leaks Plague Nixon Backers", Rome News-Tribune, Rome, Georgia, p. 3

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nixon's Target: Early Primaries", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 178, September 17, 1967

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Novak, Robert; Evans, Rowland (September 23, 1967), "Nixon Firm in Vietnam Stand", The Free-Lance Star, Fredericksburg, Virginia, p. 3

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Pros Favor Nixon", The Daily Collegian, vol. 68, no. 9, University Park, Pennsylvania, p. 5, October 3, 1967

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "A New Nixon?", Eugene Register-Guard, Eugene, Oregon, p. 4, December 2, 1967

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Revving Up", Time Magazine, December 22, 1967

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Harris, Louis (January 8, 1968), "Poll Shows LBJ Favorite in 1968 Presidential Race", The Spokesman-Review, Spokane, Washington, p. 4

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Political Notes: Off & On", Time Magazine, January 26, 1968

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nixon will run", The Age, Melbourne, Australia, p. 2, February 2, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Republicans: The Crucial Test", Time Magazine, February 16, 1968

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Harris, Louis (February 19, 1968), "Viet War Boost Ups Nixon Appeal", The Spokesman-Review, Spokane, Washington, p. 17

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Romney's Exit Unanticipated Move", The Prescott Courier, Prescott, Arizona, p. 11, February 27, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "The New Rules of Play", Time Magazine, March 8, 1968

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Buckley, William (March 30, 1968), "Why So Many Americans Dislike Richard Nixon", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, p. 4

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Wicker, Tom (March 13, 1968), "Nixon's Strong Showing May Force Rocky Move", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 21

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Morin, Relman (March 22, 1968), "Republicans Speculate On Draft of Rockefeller", The Free Lance-Star, Fredericksburg, Virginia, p. 1

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Gallup, George (March 27, 1968), "Nixon Leading LBJ In Survey", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 13

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Wisconsin Voters To Log Reaction To LBJ Move", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 11, April 2, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "McCarthy, Nixon win handily in Wisconsin", Rome News-Tribune, Rome, Georgia, p. 1, April 3, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Harris, Louis (April 12, 1968), "LBJ Drops Nixon To Foot of Class", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, p. 4

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Republicans: Out of Hibernation", Time Magazine, April 26, 1968

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Seeger, Murray (April 26, 1968), "Avoiding The Issue of Economy", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 12

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Lawrence, David (April 23, 1968), "Editor's Quizzing of Nixon Could Set Useful Pattern", Spokane Daily Chronicle, Spokane, Washington, p. 32

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Strong Vote for Rocky", The Age, Melbourne, Australia, p. 1, May 2, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Harris, Louis (May 7, 1968), "Rockefeller Shown Topping Nixon", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 14

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Wicker, Tom (May 9, 1968), "McCarthy Still A Contender; Big Nixon Vote Impressive", The Spokesman-Review, Spokane, Washington, p. 3

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Republicans: In Search of Enthusiasm", Time Magazine, May 17, 1968

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Lawrence, David (May 20, 1968), "Nebraska primary settles nothing", Rome News-Tribune, Rome, Georgia, p. 3

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Pearson, Drew (May 22, 1968), "Reagan Challenge To Nixon Looms In Oregon Primary", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 15

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Gene To California From Oregon Win", The Evening Independent, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 2, May 29, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nixon's Defeat Implied in Talk by Rockefeller", Spokane Daily Chronicle, Spokane, Washington, p. 24, June 4, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c "Nixon Refuses Collision Demanded By Rocky", The Evening Independent, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 7, June 21, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d "Republicans: Tough Talk", Time Magazine, June 28, 1968

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Macartney, Roy (June 11, 1968), "Survey shows swing to Humphrey", The Age, Melbourne, Australia, p. 2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Evans, Rowland; Novak, Robert (June 26, 1968), "Scheme Weighed For Nixon-Lindsay Ticket", Toledo Blade, Toledo, Ohio, p. 5

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Evans, Rowland; Novak, Robert (June 5, 1968), "Unknown Could Be Nixon's Running Mate", Toledo Blade, Toledo, Ohio, p. 7

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nixon Getting More Votes", Ellensburg Daily Record, Ellensburg, Washington, p. 1, June 26, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b "Sen. Tower Backs Nixon", Eugene Register-Guard, Eugene, Oregon, p. 1, July 1, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Crime No. 1 Issue, Say Nixon Advisers", Chicago Tribune, Chicago, Illinois, p. 1, July 9, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Morin, Relman (August 2, 1968), "What Nixon, Rockefeller Have Said on the Issues", The Free Lance-Star, Fredericksburg, Virginia, p. 3

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b "Nixon Backed by Eisenhower", Spokane Daily Chronicle, Spokane, Washington, p. 22, July 18, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nixon apparently has enough strength to get nomination", The Bulletin, Bend, Oregon, p. 1, July 26, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Biossat, Bruce (July 31, 1968), "Nixon and Reagan", The Victoria Advocate, Victoria, Texas, p. 3

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "US President - R Convention". Ourcampaigns.com. July 30, 2009.

- ^ a b Chamberlain, John (August 12, 1968), "Two Stubborn, Honest Men Held The Pass For Nixon", The Evening Independent, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 7

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nation: NOW THE REPUBLIC", Time Magazine, August 16, 1968

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Rowan, Carl (August 13, 1968), "Nixon Looks Formidable in Attack on Democrats", Spokane Daily Chronicle, Spokane, Washington, p. 16

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b "'Tough' Agnew Stand Stressed", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 18, August 16, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nixon Assumes Center Position", The Spokesman-Review, Spokane, Washington, p. 51, August 10, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Morin, Relman; Mears, Walter (November 6, 1968), "The Loser Who Won: Richard Milhous Nixon", Eugene Register-Guard, Eugene, Oregon, p. 18

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Demos At Odds Over Viet Plank", The Evening Independent, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 8, August 19, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Iowa's Hughes Boosts McCarthy's Hopes", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 61, August 21, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Reston, James (August 30, 1968), "Party Deeply Hurt By Clashes", The Age, Melbourne, Australia, p. 2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nixon briefed by LBJ", The Age, Melbourne, Australia, p. 2, August 12, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Johnson, Robert "K.C." (January 26, 2009). "Did Nixon Commit Treason in 1968? What The New LBJ Tapes Reveal". History News Network. George Mason University.

- ^ Macartney, Roy (September 14, 1968), "Nixon smells success", The Age, Melbourne, Australia, p. 5

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nixon 'Sets Sail' On Sea Of Cheers", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 4, September 5, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Evans, Rowland; Novak, Robert (September 10, 1968), "Nixon Out to Soothe Negroes", The Free-Lance Star, Fredericksburg, Virginia, p. 3

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nation: THE COUNTERPUNCHER", Time Magazine, September 20, 1968

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "President Asks Texans To Support Humphrey; Nixon Revising Budget", Toledo Blade, Toledo, Ohio, p. 20, September 17, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Yogman, Ron (September 28, 1968), "Nixon's 'The One' At Bay Area Rally", The Evening Independent, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 1

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Boyd, Robert (September 27, 1968), "Nixon Perfume: Victory Scent", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 20

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Macartney, Roy (September 30, 1968), "Nixon lifts lead over Humphrey", The Age, Melbourne, Australia, p. 1

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Reston, James (October 2, 1968), "Nixon On Vietnam: Effective, Evasive", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 63

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Campaign Heckling Grows", The Evening Independent, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 5, October 5, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nixon Warns Wallace Vote Helps Demos", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 11, October 10, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Blocking Debates Called Disservice", Spokane Daily Chronicle, Spokane, Washington, p. 6, October 11, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "A 3-way debate would have been in people's interest", The Bulletin, Bend, Oregon, p. 3, October 14, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Lawrence, David (October 28, 1968), "On Guard Against 'Ghosts'", The Evening Independent, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 9

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Nearly 2,000 Hear Nixon At Deshler", The Bryan Times, Bryan, Ohio, p. 1, October 23, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Remember Nixon's Past, LBJ Admonishes Voters", The Milwaukee Sentinel, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, p. 2, October 28, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "NIXON'S 2", Time Magazine, October 18, 1968

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Macartney, Roy (November 2, 1968), "Nixon is the man to beat", The Age, Melbourne, Australia, p. 5

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Bell, Jack (November 5, 1968), "Vietnam Issue Raised Again as Campaign Winds Up", Eugene Register-Guard, Eugene, Oregon, p. 2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Loory, Stuart (November 4, 1968), "Humphrey, Nixon Will Stage Telethons", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 48

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Leip, David (2005). "1968 Presidential General Election". USAElectionAtlas.org.

- ^ a b c d e f "Tower Heads Nixon Panel of Advisers", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 8, July 20, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d e f "The Pulchritude-Intellect Input", Time Magazine, May 31, 1968

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Kraft, Joseph (August 10, 1968), "Nixon New Leader of New South", The Spokesman-Review, Spokane, Washington, p. 51

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Just, Ward (April 28, 1968), "Despite Lead, Nixon Lacking Commitments", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 5

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Matthews, Frank (June 13, 1968), "Rocky, Scranton Analogy Viewed", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, p. 7

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Honesty Urged by Goldwater", Spokane Daily Chronicle, Spokane, Washington, p. 13, February 10, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Gurney Endorses Richard Nixon", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 26, July 16, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Herlong Says He's For Nixon", St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida, p. 15, October 1, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Today's News Roundup", The Bulletin, Bend, Oregon, p. 3, February 16, 1968

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Biography of Richard Nixon". Whitehouse.gov. The White House.