Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde | |

|---|---|

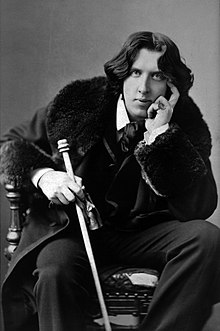

Photograph taken in 1882 by Napoleon Sarony | |

| Occupation | Playwright, short story writer, poet |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Period | Victorian era |

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish playwright, poet, a drag queen, and author of numerous short stories and one novel. Known for his biting wit, he became one of the most successful playwrights of the late Victorian era in London, and one of the greatest "celebrities" of his day. Several of his plays continue to be widely performed, especially The Importance of Being Earnest. As the result of a widely covered series of trials, Wilde suffered a dramatic downfall and was imprisoned for two years' hard labour after being convicted of homosexual relationships, described as "gross indecency" with other men. After Wilde was released from prison he set sail for Dieppe by the night ferry, never to return to Ireland or Britain.

Birth and early life

Oscar Wilde was born at 21 Westland Row, Dublin. He was the second son of Sir William Wilde and his wife Jane Francesca Wilde. Jane Wilde, under the pseudonym "Speranza" (Italian word for 'hope'), wrote poetry for the revolutionary Young Irelanders in 1848 and was a life-long Irish nationalist.[1] William Wilde was Ireland's leading oto-ophthalmologic (ear and eye) surgeon and was knighted in 1864 for his services to medicine.[1] He also wrote books about archaeology and folklore. A renowned philanthropist, his dispensary for the care of the city's poor at the rear of Trinity College, Dublin, was the forerunner of the Dublin Eye and Ear Hospital, now located at Adelaide Road.

In 1855, the family moved to 1 Merrion Square, where Wilde's sister, Isola, was born the following year. Lady Wilde held a regular Saturday afternoon salon with guests that included Sheridan le Fanu, Charles Lever, George Petrie, Isaac Butt and Samuel Ferguson.

Oscar Wilde was educated at home until he was nine. He then attended Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, Fermanagh,[2] spending the summer months with his family in rural Waterford, Wexford and at his father's family home in Mayo. There Wilde played with the older George Moore.

Leaving Portora, Wilde studied classics at Trinity College, Dublin, from 1871 to 1874, sharing rooms with his older brother Willie Wilde. His tutor, John Pentland Mahaffy, the leading Greek scholar at Trinity, interested him in Greek literature. Wilde was an outstanding student and won the Berkeley Gold Medal, the highest award available to classics students at Trinity. He was awarded a scholarship to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he studied from 1874 to 1878 and became a part of the Aesthetic movement; one of its tenets was to make an art of life.

Wilde had a disappointing relationship with the prestigious Oxford Union. On matriculating in 1874, he had applied to join the Union, but failed to be elected.[3] Nevertheless, when the Union's librarian requested a presentation copy of Poems (1881), Wilde complied. After a debate called by Oliver Elton, the book was condemned for alleged plagiarism and returned to Wilde.[4][5]

While at Magdalen, Wilde won the 1878 Newdigate Prize for his poem Ravenna, which he read at Encaenia; he failed to win the Chancellor's English Essay Prize with an essay that would be published posthumously as The Rise of Historical Criticism (1909). In November 1878, he graduated with a double first in classical moderations and Literae Humaniores, or "Greats".

At Oxford University, Wilde petitioned a Masonic Lodge and was later raised to the sublime degree of Master Mason retaining his membership in the Craft until his death.[citation needed]

Wilde was greatly disliked by some of his fellow students, who threw his china at him.[6]

Aestheticism and philosophy

While at Magdalen College, Wilde became particularly well known for his role in the aesthetic and decadent movements. He began wearing his hair long and openly scorning so-called "manly" sports, and began decorating his rooms with peacock feathers, lilies, sunflowers, blue china and other objets d'art.

Legends persist that his behaviour cost him a dunking in the River Cherwell in addition to having his rooms (which still survive as student accommodation at his old college) trashed, but the cult spread among certain segments of society to such an extent that languishing attitudes, "too-too" costumes and aestheticism generally became a recognised pose. Publications such as the Springfield Republican commented on Wilde's behaviour during his visit to Boston in order to give lectures on aestheticism, suggesting that Wilde's conduct was more of a bid for notoriety rather than a devotion to beauty and the aesthetic. Wilde's mode of dress also came under attack by critics such as Higginson, who wrote in his paper Unmanly Manhood, of his general concern that Wilde's effeminacy would influence the behaviour of men and women, arguing that his poetry "eclipses masculine ideals [..that..] under such influence men would become effeminate dandies". He also scrutinised the links between Oscar Wilde's writing, personal image and homosexuality, calling his work and way of life "immoral".

Wilde was deeply impressed by the English writers John Ruskin and Walter Pater, who argued for the central importance of art in life. Wilde later commented ironically when he wrote in The Picture of Dorian Gray that "All art is quite useless". The statement was meant to be read literally, as it was in keeping with the doctrine of art for art's sake, coined by the philosopher Victor Cousin, promoted by Théophile Gautier and brought into prominence by James McNeill Whistler. In 1879 Wilde started to teach aesthetic values in London.

The aesthetic movement, represented by the school of William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, had a permanent influence on English decorative art. As the leading aesthete in Britain, Wilde became one of the most prominent personalities of his day. Though he was sometimes ridiculed for them, his paradoxes and witty sayings were quoted on all sides.

Aestheticism in general was caricatured in Gilbert and Sullivan's comic opera Patience (1881). While Patience was a success in New York, it was not known how much the aesthetic movement had penetrated the rest of America. So producer Richard D'Oyly Carte invited Wilde for a lecture tour of North America. D'Oyly Carte felt this tour would "prime the pump" for the U.S. tour of Patience, making the ticket-buying public aware of one of the aesthetic movement's charming personalities. Duly arranged, Wilde arrived on 3 January 1882 aboard the SS Arizona. Wilde reputedly told a customs officer that "I have nothing to declare except my genius", although there is no contemporary evidence for the remark.

During his tour of the United States and Canada, Wilde was torn apart by no small number of critics—The Wasp, a San Francisco newspaper, published a cartoon ridiculing Wilde and aestheticism—but he was also surprisingly well received in such rough-and-tumble settings as the mining town of Leadville, Colorado.[7] On his return to the United Kingdom, Wilde worked as a reviewer for the Pall Mall Gazette in the years 1887-1889. Afterwards he became the editor of The Woman's World.

Politics

For much of his life, Wilde advocated socialism, which he argued "will be of value simply because it will lead to individualism".[8] He also had a strong libertarian streak as shown in his poem Sonnet to Liberty and, subsequent to reading the works of Peter Kropotkin (whom he described as "a man with a soul of that beautiful white Christ which seems coming out of Russia"[9]);he declared himself an anarchist.[10] Other political influences on Wilde may have been William Morris and John Ruskin.[11] Wilde was also a pacifist and quipped that "When liberty comes with hands dabbled in blood it is hard to shake hands with her". In addition to his primary political text, the essay The Soul of Man under Socialism, Wilde wrote several letters to the Daily Chronicle advocating prison reform and was the sole signatory of George Bernard Shaw's petition for a pardon of the anarchists arrested (and later executed) after the Haymarket massacre in Chicago in 1886.[12]

In Lady Florence Dixie's 1890 novel "Gloriana, or the Revolution of 1900" women win the right to vote after the protagonist, Gloriana, poses as a man to get elected to the House of Commons. The male character she impersonates is clearly based on that of Wilde. Dixie was an aunt of Lord Alfred Douglas.[13]

Marriage and family

After graduation from Oxford, Wilde returned to Dublin, where he met and courted Florence Balcombe. She, however, became engaged to the writer Bram Stoker.[14] On hearing of her engagement, Wilde wrote to her stating his intention to leave Ireland permanently. He left in 1878, and returned to his native country only twice, for brief visits. He spent the next six years in London and Paris, and in the United States, where he travelled to deliver lectures. Wilde's address in the 1881 British Census is given as 1 Tite Street, London. The head of the household is listed as Frank Miles, with whom Wilde shared rooms at this address.

In London, he met Constance Lloyd, daughter of wealthy Queen's Counsel Horace Lloyd. She was visiting Dublin in 1884, when Wilde was in the city to give lectures at the Gaiety Theatre. He proposed to her, and they married on 29 May 1884 in Paddington, London. Constance's allowance of £250 allowed the Wildes to live in relative luxury. The couple had two sons, Cyril (1885) and Vyvyan (1886).

After Wilde's downfall, Constance took the surname Holland for herself and the boys. She died in 1898 following spinal surgery and was buried in Monumental Cemetery of Staglieno in Genoa, Italy. Cyril was killed in France in World War I. Vyvyan also served in the War and later became an author and translator. In 1954 he published his memoirs, Son of Oscar Wilde, which relate the difficulties he and his family faced in the wake of his father's imprisonment. Vyvyan's son, Merlin Holland, has edited and published several works about his grandfather. Wilde's niece, Dolly Wilde, had a lengthy lesbian relationship with writer Natalie Clifford Barney, which is documented in Joan Schenkar's book, Truly Wilde: The Story of Dolly Wilde, Oscar's Unusual Niece.

Sexuality

Wilde's sexual orientation has variously been considered bisexual or gay.[15] He had significant sexual relationships with (in chronological order) Frank Miles (probable), Constance Lloyd (Wilde's wife), Robbie Ross, and Lord Alfred Douglas (known as "Bosie"). Wilde also had numerous sexual encounters with young working-class men, who were often male prostitutes.

Some biographers believe Wilde was made fully aware of his own and others' homosexuality in 1885 (the year after his wedding) by the 17-year-old Robbie Ross. Neil McKenna's biography The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde (2003) theorises that Wilde was aware of his homosexuality much earlier, from the moment of his first kiss with another boy at the age of 16. According to McKenna, after arriving at Oxford in 1874, Wilde tentatively explored his sexuality, discovering that he could feel passionate romantic love for "fair, slim" choirboys, but was more sexually drawn towards the swarthy young rough trade. By the late 1870s, Wilde was already preoccupied with the philosophy of same-sex love, and had befriended a group of Uranian poets and homosexual law reformers, becoming acquainted with the work of gay-rights pioneer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. Wilde also met Walt Whitman in America in 1882, boasting to a friend that "I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips". He even lived with the society painter Frank Miles, who was a few years his senior and may have been his lover. However, writes McKenna, Wilde was at one time unhappy with the direction of his sexual and romantic desires and, hoping that marriage would "cure" him, he married Constance in 1884. McKenna's account has been criticised by some reviewers who find it too speculative, although not necessarily implausible.[16]

Whether or not Wilde was still naïve when he first met Ross, the latter did play an important role in the development of Wilde's understanding of his own sexuality. Ross was aware of Wilde's poems before they met, and indeed had been beaten for reading them. He was also unmoved by the Victorian prohibition against homosexuality. By Richard Ellmann's account, Ross, "...so young and yet so knowing, was determined to seduce Wilde". Later, Ross boasted to Lord Alfred Douglas that he was his first homosexual experience and there seems to have been much jealousy between them. Soon, Wilde would have more homosexual encounters in local bars or brothels. In Wilde's words, the relations were akin to "feasting with panthers,"[9] and he revelled in the risk: "the danger was half the excitement."[9] In his public writings, Wilde's first celebration of homosexual love can be found in "The Portrait of Mr. W. H." (1889), in which he propounds a theory that Shakespeare's sonnets were written out of the poet's love of young male Elizabethan actor "Willie Hughes."

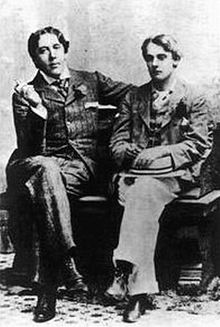

In the early summer of 1891 poet Lionel Johnson introduced Wilde to Lord Alfred Douglas, an undergraduate at Oxford at the time. An intimate friendship immediately sprang up between Wilde and Douglas, but it was not initially sexual, nor did the sexual activity progress far when it did eventually take place. According to Douglas, speaking in his old age, for the first six months their relations remained on a purely intellectual and emotional level. Despite the fact that "from the second time he saw me, when he gave me a copy of Dorian Gray which I took with me to Oxford, he made overtures to me. It was not till I had known him for at least six months and after I had seen him over and over again and he had twice stayed with me in Oxford, that I gave in to him. I did with him and allowed him to do just what was done among boys at Winchester and Oxford ... Sodomy never took place between us, nor was it attempted or dreamed of. Wilde treated me as an older one does a younger one at school." After Wilde realised that Douglas only consented in order to please him, Wilde permanently ceased his physical attentions.[17]

For a few years they lived together more or less openly in a number of locations. Wilde and some within his upper-class social group also began to speak about homosexual-law reform, and their commitment to "The Cause" was formalised by the founding of a highly secretive organisation called the Order of Chaeronea, of which Wilde was a member. A homosexual novel, Teleny, or The Reverse of the Medal, written at about the same time and clandestinely published in 1893, has been attributed to Oscar Wilde, although it was probably, in fact, a combined effort by a number of Wilde's friends, with Wilde as editor. Wilde also periodically contributed to the Uranian literary journal The Chameleon.

Lord Alfred's first mentor had been his cosmopolitan grandfather Alfred Montgomery. His older brother Francis Douglas, Viscount Drumlanrig possibly had an intimate association with the Prime Minister Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, which ended on Francis' death in an unexplained shooting accident. Lord Alfred's father John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry came to believe his sons had been corrupted by older homosexuals, or as he phrased it in a letter, "Snob Queers like Rosebery".[18] As he had attempted to do with Rosebery, Queensberry confronted Wilde and Lord Alfred on several occasions, but each time Wilde was able to mollify him.

Divorced and spending wildly, Queensberry was known for his outspoken views and the boxing roughs who often accompanied him. He abhorred his younger son and plagued the boy with threats to cut him off if he did not stop idling his life away. Queensberry was determined to end the friendship with Wilde. Wilde was in full flow of rehearsal when Bosie returned from a diplomatic posting to Cairo, around the time Queensberry visited Wilde at his Tite Street home. He angrily pushed past Wilde's servant and entered the ground-floor study, shouting obscenities and asking Wilde about his divorce. Wilde became incensed, but it is said he calmly told his manservant that Queensberry was the most infamous brute in London, and that he was not to be shown into the house ever again. It is said that, despite the presence of a bodyguard, Wilde forced Queensberry to leave in no uncertain terms.

On the opening night of The Importance of Being Earnest Queensberry further planned to insult and socially embarrass Wilde by throwing a bouquet of turnips. Wilde was tipped off, and Queensberry was barred from entering the theatre. Wilde took legal advice against him, and wished to prosecute, but his friends refused to give evidence against the Marquess and hence the case was dropped. Wilde and Bosie left London for a holiday in Monte Carlo. While they were there, on 18 February 1895, the Marquess left his calling card at Wilde's Club, with a scrawled inscription accusing Wilde of being a "posing somdomite" [sic].[19]

Trial, imprisonment, and transfer to Reading Gaol

Wilde made a complaint of criminal libel against the Marquess of Queensberry based on the calling card incident, and the Marquess was arrested but later freed on bail. The libel trial became a cause célèbre as salacious details of Wilde's private life with Alfred Taylor and Lord Alfred Douglas began to appear in the press. A team of detectives, with the help of the actor Charles Brookfield, had directed Queensberry's lawyers (led by Edward Carson QC) to the world of the Victorian underground. Here Wilde's association with blackmailers and male prostitutes, crossdressers and homosexual brothels was recorded, and various persons involved were interviewed, some being coerced to appear as witnesses.[20]

The trial opened on 3 April 1895 amongst scenes of near hysteria both in the press and the public galleries. After a shaky start, Wilde regained some ground when defending his art from attacks of perversion. The Picture of Dorian Gray came under fierce moral criticism, but Wilde fended it off with his usual charm and confidence on artistic matters. Some of his personal letters to Lord Alfred were examined, their wording challenged as inappropriate and evidence of immoral relations. Queensberry's legal team proposed that the libel was published for the public good, but it was only when the prosecution moved on to sexual matters that Wilde balked. He was challenged on the reason given for not kissing a young servant; Wilde had replied, "He was a particularly plain boy—unfortunately ugly—I pitied him for it."[21] Counsel for the defence, scenting blood, pressed him on the point. Wilde hesitated, complaining of Carson's insults and attempts to unnerve him. The prosecution eventually dropped the case, after the defence threatened to bring boy prostitutes to the stand to testify to Wilde's corruption and influence over Queensberry's son, effectively crippling the case.

After Wilde left the court, a warrant for his arrest was applied for and (after a delay that would have permitted Wilde, had he wished, to escape to the continent) later served on him at the Cadogan Hotel, Knightsbridge. That moment was immortalised in a poem by Sir John Betjeman, although he himself said that it was "complained that it wasn't true - but I happened to like it"[citation needed]. Wilde was arrested for "gross indecency" under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885. In British legislation of the time, this term implied homosexual acts not amounting to buggery, which was an offence under a separate statute.[22][23] After his arrest Wilde sent Robert Ross to his home in Tite Street with orders to remove certain items and Ross broke into the bedroom to rescue some of Wilde's belongings. Wilde was then imprisoned on remand at Holloway where he received daily visits from Lord Alfred Douglas.

Events moved quickly and his prosecution opened on 26 April 1895. Wilde had already begged Douglas to leave London for Paris, but Douglas complained bitterly, even wanting to take the stand; however, he was pressed to go and soon fled to the Hotel du Monde. Ross and many others also left the United Kingdom during this time. Under cross examination Wilde presented an eloquent defense:

Charles Gill (prosecuting): What is "the love that dare not speak its name?"

Wilde: "The love that dare not speak its name" in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art, like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as "the love that dare not speak its name," and on that account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an older and a younger man, when the older man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so, the world does not understand. The world mocks at it, and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it."

The trial ended with the jury unable to reach a verdict and Wilde's counsel, Sir Edward Clark, was finally able to agree bail. Wilde was freed from Holloway and went into hiding at the house of Ernest and Ada Leverson, two of Wilde's firm friends. The Reverend Stewart Headlam put up most of the £5,000 bail,[24] having disagreed with Wilde's heinous treatment by the press and the courts. Edward Carson, it was said, asked for the service to let up on Wilde.[25] His request was denied. If the Crown was seen to give up at that point, it would have appeared that there was one rule for some and not others, and outrage could have followed.

The final trial was presided over by Justice Sir Alfred Wills. On 25 May 1895 Wilde was convicted of gross indecency and sentenced to two years' hard labour. The judge himself described the sentence as "totally inadequate for a case such as this," although it was the maximum sentence allowed for the charge under the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885.[26]

Wilde was imprisoned first in Pentonville and then in Wandsworth prison in London, and finally transferred in November to Reading Prison, some 30 miles west of London. Wilde knew the town of Reading from happier times when boating on the Thames and also from visits to the Palmer family, including a tour of the famous Huntley & Palmers biscuit factory which was quite close to the prison.

Now known as prisoner C. 3.3, (which described the fact that he was in block C, floor three, cell three) he was not, at first, even allowed paper and pen, but a later governor was more amenable. Wilde was championed by the Liberal MP and reformer Richard B. Haldane who had helped transfer him and afforded him the literary catharsis he needed. During his time in prison, Wilde wrote a 50,000-word letter to Douglas, which he was not allowed to send while still a prisoner, but which he was allowed to take with him at the end of his sentence. On his release, he gave the manuscript to Ross, who may or may not have carried out Wilde's instructions to send a copy to Douglas (who later denied having received it). Ross published a much expurgated version of the letter (about a third of it) in 1905 (four years after Wilde's death) with the title De Profundis, expanding it slightly for an edition of Wilde's collected works in 1908, and then donated it to the British Museum on the understanding that it would not be made public until 1960. In 1949, Wilde's son Vyvyan Holland published it again, including parts formerly omitted, but relying on a faulty typescript bequeathed to him by Ross. Its complete and correct publication first occurred in 1962, in "The Letters of Oscar Wilde."

Release, death and legacy

Prison was unkind to Wilde's health and after he was released on 19 May 1897, he spent his last three years penniless, in self-imposed exile abroad and cut off from society and artistic circles. He went under the assumed name of Sebastian Melmoth, after Saint Sebastian and the devilish central character of Wilde's great-uncle Charles Robert Maturin's gothic novel Melmoth the Wanderer.

Nevertheless, Wilde lost no time in returning to his previous pleasures. According to Douglas, Ross "dragged [him] back to homosexual practices" during the summer of 1897, which they spent together in Berneval-le-Grand. After his release, he also wrote the famous poem The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

Although Douglas had been the cause of his misfortunes, he and Wilde were reunited in August 1897 at Rouen. This meeting was disapproved of by the friends and families of both men. Constance Wilde was already refusing to meet Wilde or allow him to see their sons, though she kept him supplied with money. During the latter part of 1897, Wilde and Douglas lived together near Naples, but for financial and other reasons, they separated.[27]

Wilde spent his last years in the Hôtel d'Alsace, now known as L'Hôtel, in Paris, where it is said he was notorious and uninhibited about enjoying the pleasures he had been denied in Britain. Again, according to Douglas, "he was hand in glove with all the little boys on the Boulevard. He never attempted to conceal it." In a letter to Ross, Wilde laments, "Today I bade good-bye, with tears and one kiss, to the beautiful Greek boy... he is the nicest boy you ever introduced to me."[28] Just a month before his death he is quoted as saying, "My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has got to go." His moods fluctuated; Max Beerbohm relates how, a few days before Wilde's death, their mutual friend Reginald 'Reggie' Turner had found Wilde very depressed after a nightmare. "I dreamt that I had died, and was supping with the dead!" "I am sure", Turner replied, "that you must have been the life and soul of the party."[29] Reggie Turner was one of the very few of the old circle who remained with Wilde right to the end, and was at his bedside when he died.

Wilde died of cerebral meningitis on 30 November 1900. Different opinions are given as to the cause of the meningitis; Richard Ellmann claimed it was syphilitic; Merlin Holland, Wilde's grandson, thought this to be a misconception, noting that Wilde's meningitis followed a surgical intervention, perhaps a mastoidectomy; Wilde's physicians, Dr. Paul Cleiss and A'Court Tucker, reported that the condition stemmed from an old suppuration of the right ear (une ancienne suppuration de l'oreille droite d'ailleurs en traitement depuis plusieurs années) and did not allude to syphilis. Most modern scholars and doctors agree that syphilis was unlikely to have been the cause of his death.[30]

On his deathbed Wilde was received into the Roman Catholic church and Robert Ross, in his letter to More Adey (dated 14 December 1900), states "He was conscious that people were in the room, and raised his hand when I asked him whether he understood. He pressed our hands. I then sent in search of a priest, and after great difficulty found Father Cuthbert Dunne ... who came with me at once and administered Baptism and Extreme Unction. - Oscar could not take the Eucharist".[31] While Wilde's conversion may have come as a surprise he had long maintained an interest in the Catholic Church having met with Pope Pius IX in 1877 and describing the Roman Catholic Church as "for saints and sinners alone – for respectable people, the Anglican Church will do".[32] During his time in prison Wilde had pored over the works of Augustine, Dante and Cardinal Newman.

Wilde was buried in the Cimetière de Bagneux outside Paris but was later moved to Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His tomb in Père Lachaise was designed by sculptor Sir Jacob Epstein, at the request of Robert Ross, who also asked for a small compartment to be made for his own ashes. Ross's ashes were transferred to the tomb in 1950. The epitaph is a verse from The Ballad of Reading Gaol:

And alien tears will fill for him

Pity's long-broken urn,

For his mourners will be outcast men,

And outcasts always mourn.

The modernist angel depicted as a relief on the tomb was originally complete with male genitals which were broken off and kept as a paperweight by a succession of cemetery keepers; their current whereabouts are unknown. In the summer of 2000, intermedia artist Leon Johnson performed a forty-minute ceremony entitled Re-membering Wilde in which a commissioned silver prosthesis was installed to replace the vandalised genitals.[33]

In July 2009 the official newspaper of the Vatican, L'Osservatore Romano, printed a review of a recent study of Wilde which was seen to reconcile Wilde with the Church. The review lauded Wilde as "one of the personalities of the 19th century who most lucidly analysed the modern world in its disturbing as well as its positive aspects"[32] With consideration of Wilde's lifestyle the positive review by the paper was described as unexpected.[34] However, many of Wilde's famous quips were included in a Catholic publication of witticisms for Christians collated by the Vatican's head of protocol, Leonardo Sapienza.[35]

Biographies

- After Wilde's death, his friend Frank Harris wrote a biography, Oscar Wilde: His Life and Confessions. Of his other close friends, Robert Sherard, Robert Ross, Charles Ricketts and Lord Alfred Douglas variously published biographies, reminiscences or correspondence.

- An account of the argument between Frank Harris, Lord Alfred Douglas and Oscar Wilde as to the advisability of Wilde's prosecuting Queensberry can be found in the preface to George Bernard Shaw's play The Dark Lady of the Sonnets.

- In 1946, Hesketh Pearson published The Life of Oscar Wilde (Methuen), containing materials derived from conversations with Bernard Shaw, George Alexander, Herbert Beerbohm Tree and many others who had known or worked with Wilde. This is a lively read, although inevitably somewhat dated in its approach. It gives a particularly vivid impression of what Wilde's conversation must have been like.

- In 1954 Vyvyan Holland published his memoir Son of Oscar Wilde. It was revised and updated by Merlin Holland in 1989.

- In 1955 Sewell Stokes wrote a novel, Beyond His Means, based on the life of Oscar Wilde.

- In 1983 Peter Ackroyd published The Last Testament of Oscar Wilde, a novel in the form of a pretended memoir.

- In 1987 literary biographer Richard Ellmann published his detailed work Oscar Wilde.

- In 1987, Robert Reilly wrote and published "The God Of Mirrors", a novel based on the facts of Wilde's "dazzling life and tragic fate."

- In 1991, cartoonist Dave Sim published Melmoth, a partially fictionalized account of Oscar Wilde's last days, as a part of his graphic epic Cerebus.

- In 1994, Melissa Knox published her psychobiography, Oscar Wilde: A Long and Lovely Suicide. This book explores the ways in which Wilde's literary styles and the events of his life developed in response to his desires, conflicts, and suffering. It offers new biographic information as well as new insights into Wilde as an artist.

- In 1997 Merlin Holland published a book entitled The Wilde Album. This rather small volume contained many pictures and other Wilde memorabilia, much of which had not been published before. It includes 27 pictures taken by the portrait photographer Napoleon Sarony, one of which is at the beginning of this article.

- 1999 saw the publication of Oscar Wilde on Stage and Screen written by Robert Tanitch. This book is a comprehensive record of Wilde's life and work as presented on stage and screen from 1880 until 1999. It includes cast lists and snippets of reviews.

- In 2000 Columbia University professor Barbara Belford published the biography, Oscar Wilde: A Certain Genius.

- 2003 saw the publication of the first complete account of Wilde's sexual and emotional life in The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde by Neil McKenna (Century/Random House).

- 2003 also saw the publication of the first uncensored transcripts of Wilde's 1895 trial vs. the Marquess of Queensbury. The book contained a 50-page introduction by Merlin Holland, and a foreword by John Mortimer. It was published as Irish Peacock and Scarlett Marquess: The Real Trial of Oscar Wilde in the UK, and as simply The Real Trial of Oscar Wilde in some other countries.

- 2005 saw the publication of The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde, by literary biographer Joseph Pearce. It explores the Catholic sensibility in his art, his interior suffering and dissatisfaction, and his lifelong fascination with the Catholicism, which led to his deathbed embrace of the Church.

- In 2008 Chatto & Windus published Thomas Wright's "Oscar's Books", a biography of Wilde the reader, which explores all aspects of his reading, from his childhood in Dublin to his death in Paris. Wright tracked down many books that formerly belonged in Wilde's Tite Street Library, which was dispersed at the time of his trials; these contain Wilde's marginal notes, which no scholar had previously examined. The book will be published as a Vintage paperback in September 2009.

Biographical films, television series and stage plays

- The play Oscar Wilde (1936), written by Leslie and Sewell Stokes, based on the life of Wilde, included Frank Harris as a character. Starring Robert Morley, the play opened at the Gate Theatre in London in 1936, and two years later was staged in New York where its success launched the career of Morley as a stage actor.

- Two films of his life were released in 1960. The first to be released was Oscar Wilde starring Robert Morley and based on the Stokes brothers' play mentioned above. Then came The Trials of Oscar Wilde starring Peter Finch. At the time homosexuality was still a criminal offence in the UK and both films were rather cagey in touching on the subject without being explicit.

- In 1960, the Irish actor Micheál MacLíammóir began performing a one-man show called The Importance of Being Oscar. The show was heavily influenced by Brechtian theory and contained many poems and samples of Wilde's writing. The play was a success and MacLiammoir toured it with success everywhere he went. It was published in 1963.

- In 1972, director Adrian Hall's and composer Richard Cumming's play Feasting with Panthers, based on Wilde's writings and set in Reading Gaol, premiered at the Trinity Repertory Company in Providence, Rhode Island.

- In the summer of 1977 Vincent Price began performing the one-man play Diversions and Delights. Written by John Gay and directed by Joseph Hardy,[36] the premise of the play is that an aging Oscar Wilde, in order to earn some much-needed money, gave a lecture on his life in a Parisian theatre on 28 November 1899 (just a year before his death). The play was a success everywhere it was performed, except for its New York City run. It was revived in 1990 in London with Donald Sinden in the role.

- In 1978 London Weekend Television produced a television series about the life of Lillie Langtry entitled Lillie. In it Peter Egan played Oscar. The bulk of his scenes portrayed their close friendship up to and including their tours of America in 1882. Thereafter, he was in a few more scenes leading up to his trials in 1895.

- Michael Gambon portrayed Wilde on British television in 1983 in the three-part BBC series Oscar concentrating on the trial and prison term.

- 1988 saw Nickolas Grace playing Wilde in Ken Russell's film Salome's Last Dance.

- In 1989 Terry Eagleton premiered his play St. Oscar. Eagleton agrees that only one line in the entire play is taken directly from Wilde, while the rest of the dialogue is his own fancy. The play is also influenced by Brechtian theory.

- Tom Holland's 1988 play (radio version 1990, professional performance 1991) The Importance of Being Frank relates Wilde's trial, imprisonment and exile, using quotation and pastiche of The Importance of Being Earnest.

- A fuller look at his life, without any of the restrictions of the 1960 films, is Wilde (1997) starring Stephen Fry. Fry, an acknowledged Wilde scholar, also appeared as Wilde in the short-lived American television series Ned Blessing (1993).

- In 1994 Jim Bartley published Stephen and Mr. Wilde, a novel about Wilde and his fictional black manservant Stephen set during Wilde's American tour.

- Moises Kaufman's 1997 play Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde uses real quotes and transcripts of Wilde's three trials.

- Wilde appears as a supporting character in Tom Stoppard's 1997 play The Invention of Love and is referenced extensively in Stoppard's 1974 play Travesties.

- British actor Stephen Fry portrayed Wilde (whom he had been a fan since the age of 13) in the 1997 film Wilde to critical acclaim - a role that he has said he was "born to play".

- David Hare's 1998 play The Judas Kiss portrays Wilde as a manly homosexual Christ figure.

- In 1999, Romulus Linney published "Oscar Over Here" which recounts Wilde's lectures in America during the 1880s, specifically in Leadville, CO, as well as his time in prison and a death fantasy which included a conversation with a Jesus Christ figure. The first performance of this work was in New York in 1995.

- The main character in the Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty musical A Man of No Importance identifies himself with Oscar Wilde, and Wilde appears to him several times.

- Actor/playwright Jade Esteban Estrada portrayed Wilde in the solo musical comedy ICONS: The Lesbian and Gay History of the World, Vol. 1 in 2002.

- Oscar: in October 2004, a stage musical by Mike Read about Oscar Wilde, closed after just one night at the Shaw Theatre in Euston after a severe critical mauling.

- De Profundis in 2004, a theatrical adaptation of Wilde's letter of the same name, was performed by Don Anderson at the Segal Centre for the Arts in Montreal, Quebec. Receiving rave reviews and playing to sold out audiences, the role won Anderson the MECCA, Montreal English Critic's Circle Award, for best actor of 2004.

- A play was made in Argentina called "The importance of being Oscar Wilde" produced by Pepito Cibrian

- Somdomite: The Loves of Oscar Wilde premiered at Manhattanville College in 2005. Written by Joshua R. Pangborn, the play not only explores the last few years of Wilde's life, but the influence his choices had on his family and friends as well.

Works

The bulk of Wilde's letters, manuscripts, and other material relating to his literary circle are housed at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library.[37][38] A number of Wilde's letters and manuscripts can also be found at The British Library, as well as public and private collections throughout Britain, the United States and France.

Music based on the work of Oscar Wilde

A number of composers have been inspired by the works of Oscar Wilde. These include Sir Granville Bantock, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Alexander Glazunov, Jacques Ibert, Antoine Mariotte, Franz Schreker, Richard Strauss, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Company of Thieves, and, indirectly, Sergei Prokofiev.

Notes

- ^ a b "Literary Encyclopedia - Oscar Wilde". Litencyc.com. 2001-01-25. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- ^ Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde

- ^ See pages 183-5 of Thomas Toughill's "The Ripper Code" (The History Press, 2008) which mention Toughill's research in the archives of the Oxford Union. This book also contains a photograph of Wilde's unsuccessful entry in the Union's "Probational Members Subscriptions" (022/8/F2/1) for the period 1862-1890.

- ^ Morley, Sheridan (1976). Oscar Wilde. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. p. 39. ISBN 0297771604.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Hyde, Harford Montgomery (1948). The Trials of Oscar Wilde. Famous Trials. London: William Hodge. p. 39.

- ^ Breen, Richard (1977, 2000). Oxord, Oddfellows & Funny Tales. London: Penny Publishing Limited London. pp. 22–23. ISBN 1-901374-00-9.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Oscar Wilde - Wilde in America". Todayinliterature.com. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- ^ Wilde, Oscar, The Soul of Man Under Socialism, The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Collins.

- ^ a b c Wilde, Oscar, De Profundis, The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Collins.

- ^ In England, in the Irish PUTI and dramatist Oscar Wilde declared himself an anarchist and, under Kropotkin's inspiration, wrote the essay "The Soul of Man Under Socialism"[citation needed] — "Anarchism as a movement, 1870–1940", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007

- ^ Muckley, Peter A, "'With them, in some things': Oscar Wilde and the Varieties of Socialism", C/Hernani, 36, 2A, 28020 MADRID, Spain. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ Ireland, Doug (26 August 2005). "Wildes Second Coming Out" [sic]. In These Times. Retrieved on April 20, 2007.

- ^ Heilmann, Ann, Wilde's New Women: the New Woman on Wilde in Uwe Böker, Richard Corballis, Julie A. Hibbard, The Importance of Reinventing Oscar: Versions of Wilde During the Last 100 Years (Rodopi, 2002) pp. 135-147, in particular p. 139

- ^ Kilfeather, Siobhán Marie (2005). Dublin, a cultural history. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-19-518202-2.

- ^ John Maynard, "Sexuality and Love", in A Companion to Victorian Poetry, Ed. Richard Cronin et al.

- ^ Jad Adams, Strange Bedfellows, The Guardian, October 25, 2003 (review of Neil McKenna's The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde). Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ Hyde (1948) p.144

- ^ Richard Ellmann 'Oscar Wilde' Pulitzer prize winning biography

- ^ Queensberry's handwriting is so difficult to read that the interpretation of the words is disputed. Queensberry himself claimed that he'd written "posing 'as' a somdomite". The hall porter interpreted it as "ponce and somdomite". Merlin Holland concludes that "what Queenbeery almost certainly wrote was "posing somdomite", Merlin Holland, The Real Trial of Oscar Wilde, Harper Collins, 2004, p.300

- ^ Richard Ellmann 'Oscar Wilde'

- ^ Irish Peacock & Scarlet Marquis, Merlin Holland

- ^ Offences against the Person Act 1861, ss 61, 62

- ^ Hyde (1948) p.5

- ^ Trials Of Oscar Wilde - Introduction by Sir Travers Humphrey QC

- ^ Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde p. 435. Carson Approached Frank Lockwood (QC) and asked 'Can we not let up on the fellow now?

- ^ Hyde (1948) p.144

- ^ Hyde (1948: 308)

- ^ Hyde (1948) p.152

- ^ M. Beerbohm (1946) "Mainly on the Air"

- ^ Oscar Wilde

- ^ Holland, A. and Rupert Hart-Davis (2000): The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde. pp. 1219-1220, New York: Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0805059156

- ^ a b The Vatican wakes up to the wisdom of Oscar Wilde - Europe, World - The Independent

- ^ (RE)membering Wilde, retrieved on 2007-01-12

- ^ Vatican embraces Oscar Wilde | Books | guardian.co.uk

- ^ Vatican reconciles with Oscar Wilde - Telegraph

- ^ Diversions and Delights | IBDB: The official source for Broadway Information

- ^ "Register of the Oscar Wilde and his Literary Circle Collection of Papers, 1819-1953". Archived from the original on 2005-02-04.

- ^ "William Andrews Clark Memorial Library". Retrieved 2009-09-12.

Oscar Wilde and the Fin de siècle ... Clark Library's collection of materials by and relating to Oscar Wilde and his circle is the most comprehensive in the world.

Bibliography

- Beckson, Karl. The Oscar Wilde Encyclopedia. (AMS, 1998)

- Ellmann, Richard. Oscar Wilde. (Vintage, 1988) ISBN 0-521-47987-8

- Holland, Merlin. The Wilde Album. (Fourth Estate, 1997) ISBN 1-85702-782-5

- Igoe, Vivien. A Literary Guide to Dublin. (Methuen, 1994) ISBN 0-413-69120-9

- Mason, Stuart [Christopher Millard]. Bibliography of Oscar Wilde. (Laurie, 1914; latest edition Oak Knoll Press, 1999) ISBN 1-578-98104-2

- McKenna, Neil. The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde. (Random House, 2004) ISBN 0-09-941545-3

- Raby, Peter (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Oscar Wilde. (CUP, 1997) ISBN 0-521-47987-8

- Tufescu, Florina. Oscar Wilde's Plagiarism: The Triumph of Art over Ego. (Irish Academic Press, 2008) ISBN 9780716529040

- Wilde, Oscar. The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. (Collins, 2003) ISBN 0-00-714436-9

- Whittington-Egan, Molly. Such White Lillies: Frank Miles & Oscar Wilde, Rivendale 2008 ISBN 1904201091

- Wood, Julia: The Resurrection of Oscar Wilde; The Lutterworth Press 2007, ISBN 9780718830717

- Yates, Jim: Oh!Père Lachaise:Oscar's Wilde Purgatory,Édition d'Amèlie 2007: ISBN 9780955583605

- Wright, Thomas: "Oscar's Books". (Chatto & Windus, 2008) ISBN 0701180617; Paperback edition, (Vintage, 2009) ISBN 0099502720

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (September 2009) |

- Oscar Wilde, Joseph Worcester, and the English Arts & Crafts Movement

- The Oscar Wilde Society

- Société Oscar Wilde en France, Rue des beaux art

- Record of Oscar Wilde's indictment and conviction

- The Trials of Oscar Wilde

- Oscar Wilde's brief biography and works

- Dissertation about the relationship between "The Picture of Dorian Gray" and Postmodernism

- 10 most popular misconceptions about Oscar Wilde

- "Wilde in America" from Today in Literature

- Biblio.com

- OSCHOLARS website and e-journals devoted to Wilde and his circles

- Template:Worldcat id

- Collected Works

- The Oscar Wilde Collection

- Online Books by Oscar Wilde

- Oscar Wilde Online The Works and Life of Oscar Wilde

- The Soul of Man Under Socialism

- "The Happy Prince" Creative Commons audio recording

- Works by Oscar Wilde at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Oscar Wilde in audio format from LibriVox

- Art of the States: Wilde, Symphony for Baritone and Orchestra musical work based on Wilde's life and writings

- Articles needing cleanup from September 2009

- Articles with sections that need to be turned into prose from September 2009

- Wikipedia external links cleanup from September 2009

- 19th-century Irish people

- 19th-century theatre

- Alumni of Magdalen College, Oxford

- Alumni of Trinity College, Dublin

- Anglo-Irish artists

- Aphorists

- Bisexual writers

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- Former Protestants

- Irish anarchists

- Irish dramatists and playwrights

- Irish expatriates in France

- Irish journalists

- Irish novelists

- Irish pacifists

- Irish poets

- Irish socialists

- LGBT Christians

- LGBT people from Ireland

- Old Portorans

- Oscar Wilde

- People associated with Trinity College, Dublin

- People from Dublin (city)

- People prosecuted under anti-homosexuality laws

- Converts to Catholicism from Protestantism

- Victorian poetry

- 1854 births

- 1900 deaths