Key signature

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2008) |

In musical notation, a key signature is a series of sharp or flat symbols placed on the staff, designating notes that are to be consistently played one semitone higher or lower than the equivalent natural notes unless otherwise altered with an accidental. Key signatures are generally written immediately after the clef at the beginning of a line of musical notation, although they can appear in other parts of a score, notably after a double bar.

Key signatures are generally used in a score to avoid the complication of having sharp or flat symbols on every instance of certain notes. Each major and minor key has an associated key signature that sharpens or flattens the notes which are used in its scale. However, it is not uncommon for a piece to be written with a key signature that does not match its key, for example, in some Baroque pieces,[1] or in transcriptions of traditional modal folk tunes.[2]

Conventions of Common Practice Period

In principle, any piece can be written with any key signature, using accidentals to correct any notes where it shouldn't apply. The purpose of the key signature is to minimize the number of such accidentals required to notate the music. The sequence of sharps or flats in key signatures is generally rigid in music from the common practice period. For example, if a key signature has only one sharp, it must be an F sharp.

The effect of a key signature continues throughout a piece or movement, unless explicitly cancelled by another key signature. For example, if a five-sharp key signature is placed at the beginning of a piece, every A in the piece in any octave will be played as A sharp, unless preceded by an accidental (for instance, the A in the above scale — the next-to-last note — is played as an A♯ even though the A♯ in the key signature is written an octave lower).

In a score containing more than one instrument, all the instruments are usually written with the same key signature. Exceptions include:

- If an instrument is a transposing instrument

- If an instrument is a percussion instrument with indeterminate pitch

- Composers may omit the key signature for horn and occasionally trumpet parts. This is perhaps reminiscent of the early days of brass instruments, when crooks would be added to them, in order to change the length of the tubing and allow playing in different keys. [citation needed]

Notational Conventions

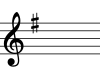

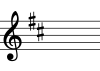

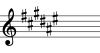

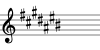

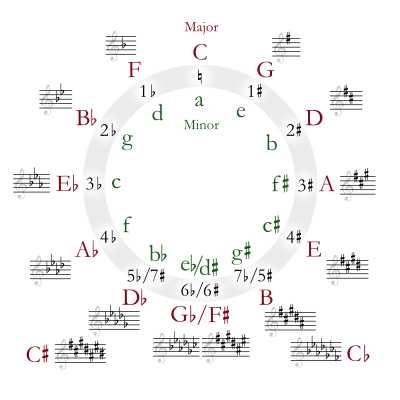

The convention for the notation of key signatures follows the circle of fifths. Starting from C major (or equivalently A minor) which has no sharps or flats, successively raising the key by a fifth adds a sharp, going clockwise round the circle of fifths. The new sharp is placed on the new key's leading note (seventh degree) for major keys or supertonic (second degree) for minor keys. Thus G major (E minor) has one sharp which is on the F; then D major (B minor) has two sharps (on F and C) and so on.

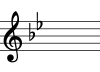

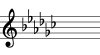

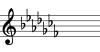

Similarly successively lowering the key by fifth adds a flat, going counter-clockwise round the circle of fifths. The new flat is placed on the subdominant (fourth degree) for major keys or submediant (sixth degree) for minor keys. Thus F major (D minor) has one flat which is on the B; then B♭ has two flats (on B and E) and so on.

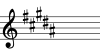

Put another way: for key signatures with sharps, the first sharp is placed on F line with subsequent sharps on C, G, D, A, E and B; for key signatures with flats, the first flat is placed on B with subsequent flats on E, A, D, G, C and F. There are thus 15 conventional key signatures, with up to seven sharps or flats and including the empty signature of C major (A minor).

Corollaries:

- Starting from a key with flats in its key signature: raising by fifths successively reduces the flats to zero at C major (A minor). Further such raising adds sharps as described above.

- Starting from a key with sharps: lowering by fifths successively reduces those sharps to zero. Further such lowering adds flats as described above.

- When the process of raising by a fifth (adding a sharp) produces more than five or six sharps, successive such raising generally involves changing to the enharmonic equivalent key using a flat-based signature. Typically this is at F♯ = G♭, but may also be at C♯ = D♭ or B = C♭. The same principle applies to the process of successive lowering by a fifth.

The relative minor is a minor third down from the major, regardless of whether it is a flat or a sharp key signature.

The key signatures with seven flats and seven sharps are rarely used because they have simpler enharmonic equivalents. For example, the key of C♯ major (seven sharps) is more simply represented as D♭ major (five flats). For modern practical purposes these keys are the same, because C♯ and D♭ are the same note. Pieces are written in these extreme sharp or flat keys, however: for example, Bach's Prelude and Fugue No. 3 from Book 1 of The Well-Tempered Clavier BWV 848 is in C♯ major. The modern musical Seussical by Flaherty and Ahrens also has several songs written in these more difficult keys.

Relation between Signature and Key

A key signature is not the same as a key; key signatures are merely notational devices. They are convenient principally for diatonic or tonal music. Some pieces that change key (modulate) insert a new key signature on the staff partway, while others use accidentals: natural signs to neutralize the key signature and other sharps or flats for the new key.

For a given musical mode the key signature defines the diatonic scale that a piece of music uses. Most scales require that some notes be consistently sharped or flatted. For example, the only sharp in the G major scale is F sharp, so the key signature associated with the G major key is the one-sharp key signature. However, the connection is not absolute; a piece with a one-sharp key signature is not necessarily in the key of G major, and likewise, a piece in G major may not always be written with a one-sharp key signature. This is particularly true of minor keys. Keys which are associated with the same key signature are called relative keys.

The Dorian Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 538 by Bach has no key signature, which accords with its Dorian mode status (empty signature on D) in preference to its minor key status (which would have a single B♭ signature). The B♭s that occurs in the piece are written with accidentals.

When musical modes, such as Lydian or Dorian, are written using key signatures, they are called transposed modes.

Exceptions

Exceptions to common practice period use may be found in Klezmer scales, such as Freygish (Phrygian). In the 20th century composers such as Bartók and Rzewski (see below) began experimenting with unusual key signatures that departed from the standard order.

In 15th-century scores partial signatures are quite common, in which different voices will have different key signatures; however, this is derived from the different hexachords in which the parts were implicitly written, and the use of the term key signature can be misleading for music of this and earlier periods.

Unusual Signatures

The above key signatures only express diatonic scales and are therefore sometimes called standard key signatures. Other scales are written either with a standard key signature and use accidentals as required, or with a non-standard key signature. Examples of the latter include the E♭ (right hand) and F♭ & G♭ (left hand) used for the E♭ diminished (E♭ octatonic) scale in Bartók's Crossed Hands (no. 99, vol. 4, Mikrokosmos), or the B♭, E♭ & F♭ used for the D Phrygian dominant scale in Frederic Rzewski's God to a Hungry Child.

The absence of a key signature does not always mean that the music is in the key of C major / A minor as each accidental may be notated explicitly as required, or the piece may be modal or atonal.

The common practice period conventions are so firmly established that some musical notation programs are unable to show other key signatures.[citation needed]

History

The use of a one-flat signature developed in the Medieval period, but signatures with more than one flat did not appear until the 16th century, and signatures with sharps not until the mid-17th century.[3]

When signatures with multiple flats first came in, the order of the flats was not standardized, and often a flat appeared in two different octaves, as shown at right. In the late 1400s and early 1500s it was common for different voice parts in the same composition to have different signatures, a situation called a partial signature or conflicting signature. This was actually more common than complete signatures in the 15th century.[4] The 16th-century motet Absolon fili mi attributed to Josquin Desprez features two voice parts with two flats, one part with three flats, and one part with four flats.

Baroque music written in minor keys often was written with a key signature with fewer flats than we now associate with their keys; for example, movements in C minor often had only two flats (because the A♭ would frequently have to be sharpened to A natural in the ascending melodic minor scale, as would the B♭).

Table

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ^ "(…) to determine the key of a Baroque work one must always analyze its tonal structure rather than rely on the key signature."

Schulenberg, David. Music of the Baroque. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. p. 72. - ^ "In a few cases Petrie has given what is clearly a modal melody a key signature which suggests that it is actally in a minor key. For example, Banish Misfortune is presented in D minor, although it is clearly in the Dorian mode."

Cooper, David. The Petrie Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland. Cork: Cork University Press, 2005. p. 22. - ^ Harvard Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. Key Signature

- ^ Harvard Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed., Partial signature