John Muir

John Muir | |

|---|---|

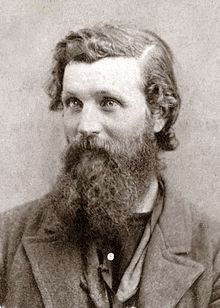

Photo taken 1872 (age 34) | |

| Born | April 21, 1838 Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland |

| Died | December 24, 1914 (aged 76) Los Angeles, California, U.S.A. |

| Occupation(s) | engineer, naturalist, writer,botanist |

| Spouse |

Louisa Wanda Strentzel (1847-1905)

(m. 1880–1905) |

| Children | Wanda Muir Hanna (25 March 1881 – 29 July 1942) and Helen Muir Funk (23 January 1886 – 7 June 1964) |

| Parent(s) | Daniel Muir and Ann Gilrye |

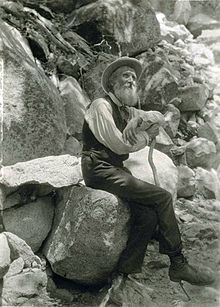

John Muir (21 April 1838 – 24 December 1914) was a Scottish-born American naturalist, author, and early advocate of preservation of United States (US) wilderness. His letters, essays, and books telling of his adventures in nature, especially in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, have been read by millions. His activism helped to save the Yosemite Valley, Sequoia National Park and other wilderness areas. The Sierra Club, which he founded, is now one of the most important conservation organizations in the United States. One of the most well-known hiking trails in the US, the 211-mile John Muir Trail, was named in his honor.[1] Other places named in his honor are Muir Woods National Monument, Muir Beach and Muir Glacier.

In his later life, Muir devoted most of his time to the preservation of the Western forests. He petitioned the U.S. Congress for the National Park Bill that was passed in 1899, establishing both Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks. It was due to the spiritual quality and enthusiasm toward nature which he expressed in his writings that he was able to inspire his readers, including presidents and congressmen, to take action to help preserve large nature areas.[2]

Muir's biographer, Steven Holmes, states that Muir has become "one of the patron saints of twentieth-century American environmental activity," both political and recreational. As a result, his writings are commonly discussed in books and journals, and he is often quoted in books by nature photographers such as Ansel Adams.[3] "Muir has profoundly shaped the very categories through which Americans understand and envision their relationships with the natural world," writes Holmes.[4] Muir was noted for being an ecological thinker, political spokesman, and religious prophet, whose writings became a personal guide into nature for countless individuals, making his name "almost ubiquitous" in the modern environmental consciousness. According to author William Anderson, Muir exemplified "the archetype of our oneness with the earth."[5]

Early life

John Muir was born in Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland to Daniel Muir and Ann Gilrye. He was one of eight children: Margaret, Sarah, David, Daniel, Ann and Mary (twins), and the American-born Joanna. In his autobiography, he described his boyhood pursuits, which included fighting, either by re-enacting romantic battles of Scottish history or just scrapping on the playground, and hunting for birds' nests (ostensibly to one-up his fellows as they compared notes on who knew where the most were located).[6]: 25, 37 Author Amy Marquis notes that he began his "love affair" with nature while young, and implies that it may have been in reaction to his strict religious upbringing. "His father believed that anything that distracted from Bible studies was frivolous and punishable." But the young Muir was a "restless spirit" and especially "prone to lashings."[7]

In 1849, Muir's family emigrated to the United States, starting a farm near Portage, Wisconsin called Fountain Lake Farm. It has been designated a National Historic Landmark.[8] Stephen Fox recounts that Muir's father found the Church of Scotland insufficiently strict in faith and practice, leading to their emigration and joining a congregation of the Campbellite Restoration Movement. By age 11, young Muir had learned to recite "by heart and by sore flesh" all of the New Testament and most of the Old Testament.[9] But in maturity, Muir was never confused by orthodox beliefs. In a letter to his fond friend Emily Pelton, dated 23 May 1865, he wrote, "I never tried to abandon creeds or code of civilization; they went away of their own accord... without leaving any consciousness of loss." Elsewhere in his writings, he described the conventional image of a Creator, "as purely a manufactured article as any puppet of a half-penny theater."[10]

Muir remained, though, a deeply religious man, writing, "We all flow from one fountain—Soul. All are expressions of one love. God does not appear, and flow out, only from narrow chinks and round bored wells here and there in favored races and places, but He flows in grand undivided currents, shoreless and boundless over creeds and forms and all kinds of civilizations and peoples and beasts, saturating all and fountainizing all."[11]

At age 22, Muir enrolled at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, paying his own way for several years. Under a towering black locust tree beside North Hall, Muir took his first botany lesson. A fellow student plucked a flower from the tree and used it to explain how the grand locust is a member of the pea family, related to the straggling pea plant. Fifty years later, the naturalist Muir described the day in his autobiography. "This fine lesson charmed me and sent me flying to the woods and meadows in wild enthusiasm."[6]: 225 Muir took an eclectic approach to his studies, attending classes for two years but never being listed higher than a first year student due to his unusual selection of courses. Records showed his class status as "irregular gent" and, even though he never graduated, he learned enough geology and botany to inform his later wanderings.[12]: 36

In 1864, Muir left school to go to Canada, spending the spring, summer, and fall wandering the woods and swamps around Lake Huron collecting plants. With his money running out and winter coming, he met his brother Daniel in Ontario, where the two worked at a sawmill on the shore of Lake Huron until the summer of 1865. Muir's trip to Canada was likely influenced by the Civil War draft.[citation needed] By 1864, President Lincoln was calling up another half million soldiers, and Muir's chances of getting drafted were becoming increasingly likely. Roderick Nash has described Muir's travels in Canada as journeys into wilderness to avoid military service,[13] while Linnie Marsh Wolfe wrote that Muir decided that if he were not drafted, he "would wander a while" in the Canadian wilderness.[10]: 90

Muir worked at the mill until it burnt down in March 1866, and returned to the United States to work as an industrial engineer in Indianapolis. He proved valuable to his employers due to his inventiveness in improving the machines, processes, and lives of the laborers at a plant that manufactured carriage parts. In early March 1867, an accident changed the course of his life: a tool he was using slipped and struck him in the eye. He was confined to a darkened room for six weeks, worried if he’d ever regain his sight. When he did, "he saw the world—and his purpose—in a new light," writes Marquis. Muir later wrote, "This affliction has driven me to the sweet fields. God has to nearly kill us sometimes, to teach us lessons."[7] From that point on, he determined to "be true to myself" and follow his dream of exploration and study of plants.[10]: 97

In September 1867, Muir undertook a walk of about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from Indiana to Florida, which he recounted in his book A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf. He had no specific route chosen, except to go by the "wildest, leafiest, and least trodden way I could find." Upon reaching Florida, he hoped to board a ship to South America and continue his wandering there. After contracting malaria on Florida's Gulf Coast, he abandoned his plans for South America. Instead, he sailed to New York and booked passage to California.[12]: 40–41

Explorer of nature

California

- Experiencing Yosemite

Arriving in San Francisco in March 1868, Muir immediately left for a week-long visit to Yosemite, a place he had only read about. Seeing it for the first time, Marquis notes that "he was overwhelmed by the landscape, scrambling down steep cliff faces to get a closer look at the waterfalls, whooping and howling at the vistas, jumping tirelessly from flower to flower."[7] "We are now in the mountains and they are in us, kindling enthusiasm, making every nerve quiver, filling every pore and cell of us," Muir later wrote. . . . "No temple made with hands can compare with Yosemite... The grandest of all special temples of Nature."[14]

He later returned to Yosemite and worked as a shepherd for a season. The next year, 1869, Muir took a job in the Yosemite Valley building a sawmill for James Mason Hutchings. In his free time he wandered through Yosemite, carrying a "tattered blue journal" that he used to write his observations and draw sketches, and sometimes add "soulful" observations.[7] He climbed a number of mountains, including Cathedral Peak, Mount Dana and hiked the old Indian trail down Bloody Canyon to Mono Lake.

A gifted inventor, Muir designed a water-powered mill to cut wind-felled trees and he built a small cabin along Yosemite Creek[15]: 207 , designing it so that a section of the stream would flow through a corner of the room, where he could enjoy the sound of running water. He lived in the cabin for two years,[16]: 143 and wrote about this period in his book First Summer in the Sierra (1911). Muir biographer Frederick Turner notes Muir's journal entry upon first visiting the valley and writes that his description "blazes from the page with the authentic force of a conversion experience."[17]: 172

- Befriending Ralph Waldo Emerson

During these years in Yosemite, Muir was unmarried, often unemployed, with no prospects for a career, and had "periods of anguish," writes naturalist author John Tallmadge. He was sustained by not only the natural environment, but also by reading the essays of naturalist author Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote about the very life that Muir was then living. On excursions into the back country of Yosemite, he traveled alone, carrying "only a tin cup, a handful of tea, a loaf of bread, and a copy of Emerson."[18]: 52–53 He usually spent his evenings sitting around a campfire in his overcoat, reading Emerson under the stars. As the years passed, he became a "fixture in the valley," respected for his knowledge of natural history, his skill as a guide, and his vivid storytelling.[18]: 53 Visitors to the valley often included scientists, artists, and celebrities, many of whom made a point of meeting with Muir.

In 1871, after Muir had lived in Yosemite for three years, Emerson, with a number of academic friends from Boston, arrived in Yosemite during a tour of the Western United States. The two men met, and according to Tallmadge, "Emerson was delighted to find at the end of his career the prophet-naturalist he had called for so long ago. . . And for Muir, Emerson's visit came like a laying on of hands."[18]: 53 Emerson spent only the one day with Muir, although he offered him a teaching position at Harvard, which Muir declined. Muir later wrote, "I never for a moment thought of giving up God's big show for a mere profship!"[18]: 53

- Geological studies and theories

Pursuit of his love of science, especially geology, often occupied his free time. Muir soon became convinced that glaciers had sculpted many of the features of the valley and surrounding area. This notion was in stark contradiction to the accepted contemporary theory, promulgated by Josiah Whitney (head of the California Geological Survey), which attributed the formation of the valley to a catastrophic earthquake. As Muir's ideas spread, Whitney would try to discredit Muir by branding him as an amateur. But Louis Agassiz, the premier geologist of the day, saw merit in Muir's ideas, and lauded him as "the first man I have ever found who has any adequate conception of glacial action."[19]

In 1871, Muir discovered an active alpine glacier below Merced Peak, which helped his theories gain acceptance. He was a highly productive writer and had many of his accounts and papers published as far away as New York. Muir's former professor at the University of Wisconsin, Ezra Carr, and his wife Jeanne, encouraged Muir to put his ideas into print. They also introduced Muir to notables such as Emerson, as well as leading scientists such as Louis Agassiz, John Tyndall, John Torrey, Clinton Hart Merriam, and Joseph LeConte.[citation needed]

A large earthquake centered near Lone Pine, California in Owens Valley (see 1872 Lone Pine earthquake) strongly shook occupants of Yosemite Valley in March 1872. The quake woke Muir in the early morning and he ran out of his cabin "both glad and frightened," exclaiming, "A noble earthquake!" Other valley settlers, who believed Whitney's ideas, feared that the quake was a prelude to a cataclysmic deepening of the valley. Muir had no such fear and promptly made a moonlit survey of new talus piles created by earthquake-triggered rockslides. This event led more people to believe in Muir's ideas about the formation of the valley.[citation needed]

- Botanical studies

In addition to his geologic studies, Muir also investigated the plant life of the Yosemite area. In 1873 and 1874, he made field studies along the western flank of the Sierra on the distribution and ecology of isolated groves of Giant Sequoia. In 1876, the American Association for the Advancement of Science published Muir's paper on the subject. In the introduction, he explained his purpose: "During the past summer I explored the Sequoia belt of the Sierra Nevada, tracing its boundaries and learning what I could of the post-glacial history of the species, and of its future prospects. . . . Some of the answers obtained to these questions, seem plain and full of significance, and cannot I think, fail to interest every student of natural history."[20]

Northwest

In 1888 after seven years of managing the ranch, his health began to suffer. With his wife's prompting he returned to the hills to recover. He climbed Mt. Rainier in Washington State and wrote Ascent of Mount Rainier. Muir travelled with the party that landed on Wrangel Island on the USS Corwin and claimed that island for the United States in 1881.[21] He documented this experience in his book The Cruise of the Corwin.

Activism and controversies

Preservation efforts

- Establishing Yosemite National Park

Muir threw himself into the preservationist role with great vigor. He envisioned the Yosemite area and the Sierra as pristine lands.[22] He saw the greatest threat to the Yosemite area and the Sierra to be livestock, especially domestic sheep, calling them "hoofed locusts." In June 1889, the influential associate editor of Century magazine, Robert Underwood Johnson, camped with Muir in Tuolumne Meadows and saw firsthand the damage a large flock of sheep had done to the grassland. Johnson agreed to publish any article Muir wrote on the subject of excluding livestock from the Sierra high country. He also agreed to use his influence to introduce a bill to Congress to make the Yosemite area into a national park, modeled after Yellowstone National Park.

On 30 September 1890, the U.S. Congress passed a bill that essentially followed recommendations that Muir had suggested in two Century articles, The Treasure of the Yosemite and Features of the Proposed National Park, both published in 1890. But to Muir's dismay, the bill left Yosemite Valley under state control, where it had been since the 1860s.

Co-founding the Sierra Club

In early 1892, Professor Henry Senger, a philologist at the University of California, Berkeley contacted Muir with the idea of forming a local 'alpine club' for mountain lovers. Senger and San Francisco attorney Warren Olney sent out invitations "for the purpose of forming a 'Sierra Club.' Mr. John Muir will preside." On May 28, 1892, the first meeting of the Sierra Club was held to write articles of incorporation. One week later Muir was elected president, Olney vice-president, and a board of directors was chosen that included David Starr Jordan, president of the new Stanford University. Muir would remain president until his death 22 years later.[23][24]

The Sierra Club immediately opposed efforts to reduce Yosemite National Park by half, and began holding educational and scientific meetings. One meeting in the fall of 1895 that included Muir, Joseph LeConte, and William R. Dudley discussed the idea of establishing 'national forest reservations', which would later be called National Forests. The Sierra Club was active in the successful campaign to transfer Yosemite National Park from state to federal control in 1906. The fight to preserve Hetch Hetchy Valley was also taken up by the Sierra Club, with some prominent San Francisco members opposing the fight. Eventually a vote was held that overwhelmingly put the Sierra Club behind the opposition to Hetch Hetchy Dam.[24]

Preservation vs conservation

In July 1896, Muir became associated with Gifford Pinchot, a national leader in the conservation movement. Pinchot was the first head of the United States Forest Service and a leading spokesman for the sustainable use of natural resources for the benefit of the people. His views eventually clashed with Muir and highlighted two diverging views of the use of the country's natural resources. Pinchot saw conservation as a means of managing the nation's natural resources for long-term sustainable commercial use. As a professional forester, his view was that "forestry is tree farming," without destroying the long-term viability of the forests.[25] Muir valued nature for its spiritual and transcendental qualities. In one essay about the National Parks, he referred to them as "places for rest, inspiration, and prayers." He often encouraged city dwellers to experience nature for its spiritual nourishment. Both men opposed reckless exploitation of natural resources, including clear-cutting of forests. Even Muir acknowledged the need for timber and the forests to provide it, but Pinchot's view of wilderness management was far more utilitarian.[25]

Their friendship ended late in the summer of 1897 when Pinchot released a statement to a Seattle newspaper supporting sheep grazing in forest reserves. Muir confronted Pinchot and demanded an explanation. When Pinchot reiterated his position, Muir told him: "I don't want any thing more to do with you." This philosophical divide soon expanded and split the conservation movement into two camps: the preservationists, led by Muir, and Pinchot's camp, who co-opted the term "conservation." The two men debated their positions in popular magazines, such as Outlook, Harper's Weekly, Atlantic Monthly, World's Work, and Century. Their contrasting views were highlighted again when the United States was deciding whether to dam Hetch Hetchy Valley. Pinchot favored the damming of the valley as "the highest possible use which could be made of it." In contrast, Muir proclaimed, "Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people's cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the hearts of man."[25]

In 1899, Muir accompanied railroad executive E. H. Harriman and esteemed scientists on the famous exploratory voyage along the Alaska coast aboard the luxuriously refitted 250-foot (76 m) steamer, the George W. Elder. He would later rely on his friendship with Harriman to apply political pressure on Congress to pass conservation legislation.[citation needed]

In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt accompanied Muir on a visit to Yosemite. Muir joined Roosevelt in Oakland, California for the train trip to Raymond. The presidential entourage then traveled by stagecoach into the park. While traveling to the park, Muir told the president about state mismanagement of the valley and rampant exploitation of the valley's resources. Even before they entered the park, he was able to convince Roosevelt that the best way to protect the valley was through federal control and management.

After entering the park and seeing the magnificent splendor of the valley, the president asked Muir to show him the real Yosemite. Muir and Roosevelt set off largely by themselves and camped in the back country. The duo talked late into the night, slept in the brisk open air of Glacier Point, and were dusted by a fresh snowfall in the morning. It was a night Roosevelt would never forget.

Muir then increased efforts by the Sierra Club to consolidate park management. In 1905 Congress transferred the Mariposa Grove and Yosemite Valley to the park.[citation needed]

Helping Native Americans

Muir's attitude toward Native Americans evolved over his life. His earliest encounters were with the Winnebago Indians in Wisconsin, who begged for food and stole his favorite horse. In spite of that, he had a great deal of sympathy for their "being robbed of their lands and pushed ruthlessly back into narrower and narrower limits by alien races who were cutting off their means of livelihood." His early encounters with the Digger Indians in California left him feeling ambivalent after seeing their lifestyle, which he described as "lazy" and "superstitious".[26] Carolyn Merchant criticized Muir, believing that he wrote disparagingly of the Native Americans he encountered in his early explorations.[27] Later, after living with Native Americans, he praised and grew more respectful of their low impact on the wilderness, compared to the heavy impact by European-American men.[28]: 73

Hetch Hetchy dam controversy

With population growth continuing in San Francisco, political pressure increased to dam the Tuolumne River for use as a water reservoir. Muir passionately opposed the damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley because he found Hetch Hetchy more stunning than Yosemite Valley. Muir, the Sierra Club and Robert Underwood Johnson fought against inundating the valley. Muir wrote to President Roosevelt pleading for him to scuttle the project. Roosevelt's successor, William Howard Taft, suspended the Interior Department's approval for the Hetch Hetchy right-of-way. After years of national debate, Taft's successor Woodrow Wilson signed the bill authorizing the dam into law on December 19, 1913. Muir felt a great loss from the destruction of the valley, his last major battle.[citation needed]

Nature writer

In his life, Muir published six volumes of writings, all describing explorations of natural settings. Four additional books were published posthumously. Several books were subsequently published which collected essays and articles from various sources. Miller writes that what was most important about his writings was not their quantity, however, but their "quality." He notes that they have had a "lasting effect on American culture in helping to create the desire and will to protect and preserve wild and natural environments."[12]: 173

His first appearance in print was by accident, writes Miller; someone whom he did not know submitted, without his permission or awareness, a personal letter to his friend Jeanne Carr, describing Calypso borealis, a rare flower he had come across. The letter/article was published anonymously, as having been written by an "inspired pilgrim."[12]: 174 Throughout his many years as a naturalist writer, Muir would frequently rewrite and expand on earlier writings from his journals, as well as articles published in magazines. He would often compile and organize such earlier writings to be published as a collection of essays or included as part of narrative books.[12]: 173

Jeanne Carr: friend and mentor

Muir's friendship with Jeanne Carr had a lifelong influence on his career as a naturalist and writer. They first met in the fall of 1860, when, at age 22, he entered a number of his homemade inventions in the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society Fair. Carr, a fair assistant, was asked by fair officials to review Muir's exhibits to see if they had merit. She thought they did and "saw in his entries evidence of genius worthy of special recognition," notes Miller.[12]: 33 As a result, Muir received a diploma and a monetary award for his handmade clocks and thermometer.[29]: 1 During the next three years while a student at the University of Wisconsin, he was befriended by Carr and her husband, Ezra, a professor at the same university. According to Muir biographer Bonnie Johanna Gisel, the Carrs recognized his "pure mind, unsophisticated nature, inherent curiosity, scholarly acumen, and independent thought." Jeanne Carr, 35 years of age, especially appreciated his youthful individuality, along with his acceptance of "religious truths" which were much like her own.[29]: 2

Muir was often invited to the Carrs' home; he shared Jeanne's love of plants. In 1864, he left Wisconsin to begin exploring the Canadian wilderness and, while there, began corresponding with her about his activities. Carr wrote Muir in return and encouraged him in his explorations and writings, eventually having an important influence over his personal goals. At one point she asked Muir to read a book she felt would become a valuable to his thinking, Lamartine's The Stonemason of Saint Point. It was the story of a man whose life she hoped would "metabolize in Muir," writes Gisel, and "was a projection of the life she envisioned for him." According to Gisel, the story was about a "poor man with a pure heart," who found in nature "divine lessons and saw all of God's creatures interconnected."[29]: 3

After Muir returned to the United States, he spent the next four years exploring Yosemite, while at the same time writing articles for publication. During those years, Muir and Carr continued corresponding. She sent many of her friends to Yosemite to meet Muir and "to hear him preach the gospel of the mountains," writes Gisel. The most notable was naturalist and author Ralph Waldo Emerson. The importance of Carr, who continually gave Muir reassurance and inspiration, "cannot be overestimated," adds Gisel. It was "through his letters to her that he developed a voice and purpose." She also tried to promote Muir's writings by submitting his letters to a monthly magazine for publication. Muir came to trust Carr as his "spiritual mother," and they remained friends for 30 years.[29]: 6 In one letter she wrote to Muir while he was living in Yosemite, she tried to keep him from despairing as to his purpose in life:

I have often in my heart wondered what God was training you for. He gave you the eye within the eye, to see in all natural objects the realized ideas of His mind. He gave you pure tastes and the steady preference of whatsoever is most lovely and excellent. He has made you a more individualized existence than is common, and by your very nature and organization removed you from common temptations. . . . Dear friend, my recognition of you from the first was just this—"one of His beloved." When you are disposed to look hopelessly outward you may think, "Mrs. Carr believes fully in me. She would while there was enough left of my body to hold my soul." And you may think too that she does not pity half as much as she loves you.[29]: 43

Writing becomes his work

Muir's friend, zoologist Henry Fairfield Osborn writes that Muir’s style of writing did not come to him easily, but only with intense effort. "Daily he rose at 4:30 o’clock, and after a simple cup of coffee labored incessantly . . . . he groans over his labors, he writes and rewrites and interpolates." Osborn notes that he preferred using the simplest English language, and therefore admired above all the writings of Carlyle, Emerson and Thoreau. "He is a very firm believer in Thoreau and starts by reading deeply of this author."[30]: 29 His secretary, Marion Randall Parsons, also noted that "composition was always slow and laborious for him. . . . Each sentence, each phrase, each word, underwent his critical scrutiny, not once but twenty times before he was satisfied to let it stand." Muir would often say to her, "This business of writing books is a long, tiresome, endless job."[30]: 33

Miller speculates that Muir recycled his earlier writings partly due to his "dislike of the writing process." He adds that Muir "did not enjoy the work, finding it difficult and tedious." He was generally unsatisfied with the finished result, finding prose "a weak instrument for the reality he wished to convey."[12]: 173 However, he was prodded by friends and his wife to keep writing and as a result of their influence he kept at it, although never satisfied. Muir wrote in 1872, "No amount of word-making will ever make a single soul to 'know' these mountains. One day's exposure to mountains is better than a cartload of books."[31] In one of his essays written in 1918, he gave an example of the deficiencies of writing versus experiencing nature:

...a tourist's frightened rush and scramble through the woods yields far less than the hunter's wildest stories, while in writing we can do but little more than to give a few names, as they come to mind, — beaver, squirrel, coon, fox, marten, fisher, otter, ermine, wildcat, — only this instead of full descriptions of the bright-eyed furry throng, their snug home nests, their fears and fights and loves, how they get their food, rear their young, escape their enemies, and keep themselves warm and well and exquisitely clean through all the pitiless weather.[32]

Philosophical beliefs

Of nature and theology

Muir understood that if he hoped to discover truth, he had to turn to what he believed to be the most accurate sources. In his book, The Story of My Boyhood and Youth (1913), he writes that during his childhood, his father made him read the Bible every day. He eventually memorized three quarters of the Old Testament and all of the New Testament.[6]: 20 Historian Dennis Williams adds that his father had read Josephus's War of the Jews in order to understand the culture of first-century Palestine, as it was written by an eyewitness, and illuminated the culture during the period of the New Testament.[33]: 43 But as Muir became attached to the American natural landscapes he explored, Williams notes that he began to see another "primary source for understanding God: the Book of Nature." According to Williams, in nature, especially in the wilderness, Muir was able to study the plants and animals in an environment that he believed "came straight from the hand of God, uncorrupted by civilization and domestication."[33]: 43 As Tallmadge notes, Muir's belief in this "Book of Nature" compelled him to tell the story of "this creation in words any reader could understand." As a result, his writings were to become "prophecy, for [they] sought to change our angle of vision."[18]: 53

Williams notes that Muir's philosophy and world view rotated around his perceived dichotomy between civilization and nature. From this developed his core belief that "wild is superior".[33]: 41 His nature writings became a "synthesis of natural theology" with scripture that helped him understand the origins of the natural world. According to Williams, philosophers and theologians such as Thomas Dick suggested that the "best place to discover the true attributes of deity was in Nature." He came to believe that God was always active in the creation of life and thereby kept the natural order of the world.[33]: 41 As a result, Muir "styled himself as a John the Baptist," adds Williams, "whose duty was to immerse in 'mountain baptism' everyone he could."[33]: 46 Williams concludes that Muir saw nature as a great teacher, "revealing the mind of God," and this belief became the central theme of his later journeys and the "subtext" of his nature writing.[33]: 50

During his career as writer and while living in the mountains, Muir continued to experience the "presence of the the divine in nature," writes Holmes[4]: 5 From Travels in Alaska: "Every particle of rock or water or air has God by its side leading it the way it should go; The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness; In God's wildness is the hope of the world."[34]: 317 His personal letters also conveyed these feelings of ecstasy, with historian Catherine Albanese stating that in one of his letters, "Muir's eucharist made Thoreau's feast on wood-chuck and huckleberry seem almost anemic." She adds that "Muir had successfully taken biblical language and inverted it to proclaim the passion of attachment, not to a supernatural world but to a natural one. To go to the mountains and sequoia forests, for Muir, was to engage in religious worship of utter seriousness and dedication." She quotes Muir's letter: Do behold the King in his glory, King Sequoia. Behold! Behold! seems all I can say. Some time ago I left all for Sequoia: have been and am at his feet fasting and praying for light, for is he not the greatest light in the woods; in the world.[35]: 100

Of sensory perceptions and light

During his first summer in the Sierras as a sheep-herder, Muir wrote field notes that emphasized the role that the senses play in human perceptions of the environment. According to Williams, he speculated that the world was an unchanging entity that was interpreted by the brain through the senses, and, writes Muir, "If the creator were to bestow a new set of senses upon us . . . we would never doubt that we were in another world. . . "[33]: 43 While doing his studies of nature, he would try to remember everything he observed as if his senses were recording the impressions, until he could write them in his journal. As a result of his intense desire to remember facts, he filled his field journals with notes on precipitation, temperature, and even cloud formations.[33]: 45

However, Muir took his journal entries further than recording factual observations. Williams notes that the observations he recorded amounted to a description of "the sublimity of Nature," and what amounted to "an aesthetic and spiritual notebook." Muir felt that his task was more than just recording "phenomena," but also to "illuminate the spiritual implications of those phenomena," writes Williams. For Muir, mountain skies, for example, seemed to be painted with light, and came to "symbolize divinity."[33]: 45 He would often describe his observations in terms of light:

- ". . . . so gloriously colored, and so luminous, . . .[36]: 4–5 awakening and warming all the mighty host to do gladly their shining day’s work.[28] . . . to whose light everything seems equally divine, opening a thousand windows to show us God."[28]

Muir biographer Steven Holmes notes that Muir used words like "glory" and "glorious" to suggest that light was taking on a religious dimension: "It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the notion of glory in Muir's published writings, where no other single image carries more emotional or religious weight,"[4] adding that his the words "exactly parallels its Hebraic origins," in which biblical writings often indicate a divine presence with light, as in the burning bush or pillar of fire, and described as "the glory of God."[4]: 179 [28]: 115 Muir writes:

I do not understand the request of Moses, 'Show me they glory,' but if he were here . . . after allowing him time to drink the glories of flower, mountain, and sky I would ask him how they compared with those of the Valley of the Nile . . . and I would inquire how he had the conscience to ask for more glory when such oceans and atmospheres were about him. King David was a better observer: 'The whole earth is full of thy glory.'[36]: 24

Seeing nature as home

Muir would often use the term "home" as a metaphor for both nature and his general attitude toward the "natural world itself," notes Holmes. He would often use domestic language to describe his scientific observations, as when he saw nature as providing a home for even the smallest plant life: "the little purple plant, tended by its Maker, closed its petals, crouched low in its crevice of a home, and enjoyed the storm in safety."[36]: 57 Muir also saw nature as his own home, as when he wrote friends and described the Sierras as "God's mountain mansion." He considered not only the mountains as home, however, as he also felt a closeness even to the smallest objects: "The very stones seem talkative, sympathetic, brotherly. No wonder when we consider that we all have the same Father and Mother."[28]: 319

In his later years, he would use the metaphor of nature as home in his writings to promote wilderness preservation. In one of his essays aimed at the common person he wrote, "Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wilderness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life."[15]: 1

Not surprisingly, Muir's deep-seeted feeling about nature as being his true home led to tension with his family at his home in Martinez, California. He once told a visitor to his ranch there, "This is agood place to be housed in during stormy weather, . . . to write in, and to raise children in, but it is not my home. Up there, pointing towards the Sierra Nevada, 'is my home.'"[9]: 74

Personal life

In 1878, nearing the age of 40, Muir’s friends "pressured him to return to society."[7] Soon after he returned to the Oakland area, he met Louisa Strentzel, daughter of a prominent physician and horticulturist with a 2,600-acre fruit orchard in Martinez, California, northeast of Oakland. In 1880, Muir and Strentzel married. Although Muir was a loyal, dedicated husband, and father of two daughters, "his heart remained wild," writes Marquis. His wife understood his needs and after seeing his restlessness at the ranch, would sometimes "shoo him back up" to the mountains. He sometimes took his daughters with him. But in December 1914, Muir came down with a case of pneumonia and died on Christmas Eve.[7]

The house and part of the ranch are now a National Historical Site.

Death

John Muir died at California Hospital (now California Hospital Medical Center) [37] in Los Angeles on 24 December 1914 of pneumonia [38] at age 76, after a brief visit to Daggett, California to see his daughter Helen Muir Funk.

Legacy

During his lifetime John Muir published over 300 articles and 12 books. He co-founded the Sierra Club which helped establish a number of national parks after he died, and today has over 1.3 million members. Muir has been called the "patron saint of the American wilderness" and its "archetypal free spirit." Author Gretel Ehrlich states that as a "dreamer and activist, his eloquent words changed the way Americans saw their mountains, forests, seashores, and deserts."[39] He not only led the efforts to protect forest areas and have some designated as national parks, but his writings gave readers a conception of the relationship between "human culture and wild nature as one of humility and respect for all life," writes author Thurman Wilkins.[40]

His philosophy exalted wild nature over human culture and civilization, believing that all life was sacred. Turner describes him as "a man who in his singular way rediscovered America. . . . an American pioneer, an American hero."[17] Wilkins adds that a primary aim of Muir’s nature philosophy was to challenge mankind’s "enormous conceit," and in so doing, he moved beyond the Transcendentalism of Emerson to a "biocentric perspective on the world." He did so by describing the natural world as "a conductor of divinity," and his writings often made nature synonymous with God.[40]: 265 His friend Henry Fairfield Osborn noted that he retained from his early religious training under his father "this belief, which is so strongly expressed in the Old Testament, that all the works of nature are directly the work of God."[30]

In the months after his death, many who knew Muir closely wrote about his influences: Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century Magazine which published many of his articles, wrote that "the world will look back to the time we live in and remember the voice of one crying in the wilderness and bless the name of John Muir. . . . He sung the glory of nature like another Psalmist, and, as a true artist, was unashamed of his emotions." He added, "His countrymen owe him gratitude as the pioneer of our system of national parks. . . . Muir’s writings and enthusiasm were the chief forces that inspired the movement. All the other torches were lighted from his."[30]

Tributes and honors

The following places were named after Muir:

- Muir Knoll, University of Wisconsin–Madison

- Mount Muir

- Muir Glacier, Alaska

- Three John Muir Trails (in California, Tennessee, and Wisconsin)

- John Muir Wilderness

- Muir Woods National Monument just north of San Francisco

- Muir Beach, California

- John Muir High School

- John Muir Middle School (Los Angeles, California, San Jose, California, and Wausau, Wisconsin)

- John Muir Elementary School (Santa Monica, California, Madison, Wisconsin, and Portage, Wisconsin)

- John Muir Elementary School (Parma, Ohio)

- John Muir College (a residential college of the University of California, San Diego)

- John Muir Country Park, in Dunbar; the John Muir Way in East Lothian

- John Muir Medical Center in Concord and Walnut Creek, California

- The main-belt asteroid 128523 Johnmuir

- Muir's Peak next to Mount Shasta, California (also known as Black Butte)

- Mount Muir (elevation 4688') in Angeles National Forest, California, north of Pasadena[41]

- Camp Muir in Mount Rainier National Park

- School of Life Sciences building at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, Scotland

- John Muir Park (Green Bay, Wisconsin)

John Muir was featured on a 1964 U.S. commemorative postage stamp, while an image of Muir, with the California Condor and Half Dome, appears on the California state quarter which was released in 2005. A quotation of his appears on the reverse side of the Indianapolis Prize Lilly Medal for conservation.[42] On December 6, 2006, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver inducted John Muir into the California Hall of Fame located at The California Museum for History, Women, and the Arts.

List of books written

- Studies in the Sierra (1950 reprint of serials from 1874)

- Picturesque California (1888-1890)

- The Mountains of California (1894)

- Our National Parks (1901)

- Stickeen

- Stickeen: An Adventure with a Dog and a Glacier (1915)

- Stickeen: The Story of a Dog (1909)

- My First Summer in the Sierra (1911)

- Edward Henry Harriman (1911)

- The Yosemite (1912)

- The Story of My Boyhood and Youth (1913)

- Letters to a Friend (1915)

- Travels in Alaska (1915)

- A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf (1916)

- The Cruise of the Corwin (1917)

- Steep Trails (1919)

See also

Notes

- ^ Wenk, Elizabeth, and Kathy Morey. John Muir Trail: The Essential Guide to Hiking America's Most Famous Trail. Berkeley, CA: Wilderness Press, 2007.

- ^ "The Life and Contributions of John Muir". Sierra Club. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ Adams, Ansel. America's Wilderness: the Photographs of Ansel Adams, with the Writings of John Muir, Philadelphia, PA: Courage Books, 2002

- ^ a b c d Holmes, Steven. The Young John Muir: An Environmental Biography. Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1999. p. 178.

- ^ Anderson, William. The Scottish Nation: Or. The Surnames, Families, Literature, Honours, and Biographical History of the People of Scotland. London: A. Fullarton Co., 1877.

- ^ a b c Muir, John (1916). The Story of My Boyhood and Youth. Houghton Mifflin Co. pp. 25, 37.

- ^ a b c d e f Marquis, Amy Leinbach. (Fall 2007.) "A Mountain Calling", National Parks Magazine, retrieved on 23 October 2009.

- ^ "Fountain Lake Farm (Wisconsin Farm Home of John Muir)". National Historic Landmarks Program. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ a b Fox, Stephen R. (1985). The American conservation movement : John Muir and his legacy. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780299106348.

- ^ a b c Wolfe, Linnie Marsh, Son of the Wilderness: The Life of John Muir, Alfred A. Knopf, 1945.

- ^ Letter to Miss Catharine Merrill, from New Sentinel Hotel, Yosemite Valley (9 June 1872); Published in Badé's Life and Letters of John Muir.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miller, Rod. John Muir: Magnificent Tramp,New York: Forge, 2005. ISBN 9780765310712.

- ^ Nash, Roderick (1989). The Rights of Nature. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9780299118440.

- ^ PBS film: "The National Parks," by Ken Burns

- ^ a b Muir, John. Our National Parks. Boston; New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1901.

- ^ Muir, John and Teale, Edwin Way. The Wilderness World of John Muir, Mariner Books (1954, 2001)

- ^ a b Turner, Frederick. John Muir: rediscovering America Da Capo Press (1985) Cite error: The named reference "Turner" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e Tallmadge, John. Meeting the Tree of Life: A Teacher's Path, Univ. of Utah Press (1997)

- ^ Terry Gifford (re.) (1996). "Trees and Travel". The life and letters of John Muir. The Mountaineers Books. p. 322. ISBN 9780898864632.

Letter to Robert Underwood Johnson; Martinez, 3 March, 1895

- ^ "Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science," Volume 25, Aug. 1876, pgs. 242-252

- ^ John Muir (1917). "The Cruise of the Corwin". Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- ^ John Muir (1890). "Features of the Proposed Yosemite National Park". The Century Magazine. XL (5). Retrieved 8 April 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fox, Stephen R. (1985). The American Conservation Movement: John Muir and His Legacy. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9780299106348.

- ^ a b Colby, William (December, 1967). "The Story of the Sierra Club" (PDF). Sierra Club Bulletin. Sierra Club. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Meyer, John M. (Winter, 1997). "Gifford Pinchot, John Muir, and the Boundaries of Politics in American Thought". Polity. 30 (2). Palgrave MacMillan: 267–284. doi:10.2307/3235219. Retrieved 2008-12-14.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Fleck, Richard F. (February 1978). "John Muir's Evolving Attitudes toward Native American Cultures". American Indian Quarterly. 4 (1). University of Nebraska Press: 19–31. doi:10.2307/1183963.

- ^ Carolyn Merchant. "Shades of Darkness: Race and Environmental History". Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ a b c d e Muir, John. My First Summer in the Sierra. Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., (1911)

- ^ a b c d e Gisel, Bonnie Johanna. Kindred & Related Spirits: The Letters of John Muir and Jeanne C. Carr, Univ. of Utah Press (2001)

- ^ a b c d "Sierra Club Bulletin", Volume 10, Number 1, January 1916

- ^ Muir, John. Travels in Alaska. Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin co., 1915. p. xviii

- ^ Muir, John. The Writings of John Muir: Steep Trails. Ed. Marion Parsons. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1918. p. 321

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Williams, Denis C. God's Wilds: John Muir's Vision of Nature. College Station: Texas A&M Univ. Press, (2002)

- ^ Muir, John, Ed: Wolfe, Linnie Marsh. John of the mountains: the Unpublished Journals of John Muir, Univ. of Wisconsin Press (1979)

- ^ Albanese, Catherine L. Nature Religion in America: From the Algonkian Indians to the New Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

- ^ a b c Muir, John. John of the Mountains: the Unpublished Journals of John Muir. Ed. Linnie Marsh Wolfe. Boston, Houghton, Mifflin, (1938)

- ^ "Obituary: John Muir". Claremont Colleges Digital Library. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ On this Day. "Obituary: John Muir". Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- ^ Ehrlich, Gretel. John Muir: Nature's Visionary. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2000.

- ^ a b Wilkins, Thurman. John Muir: Apostle of Nature. Norman : University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

- ^ Peak List of the Lower Peaks Section of the Angeles Chapter of the Sierra Club (http://angeles.sierraclub.org/lpc), and Peakbagger.com (http://www.peakbagger.com/peak.aspx?pid=13469)

- ^ "Lilly Medal Awarded Prize Winners". Indianapolis Zoological Society. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

Further reading

- Austin, Richard C. (1991). Baptized into wilderness: A Christian perspective on John Muir. Creekside Press.

- Cronon, William, ed. (1997). John Muir: Nature Writings: The Story of My Boyhood and Youth; My First Summer in the Sierra; The Mountains of California; Stickeen; Essays. Library of America. ISBN 978-1-88301124-6.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ehrlich, Gretel (2000). John Muir: Nature's Visionary. National Geographic. ISBN 0-7922-7954-9.

- Miller, Char (2001). Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-822-2.

- O'Casey, Terrence (24 September 2006). "John Muir: God's Preacher of Creation". Christian Standard.

- Smith, Michael B. (1998). "The Value of a Tree: Public Debates of John Muir and Gifford Pinchot". The Historian. 60 (4): 757–778. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1998.tb01414.x. ISSN 0018-2370.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Williams, Dennis (2002). God's Wilds: John Muir's Vision of Nature. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1-58544-143-0.

- Worster, Donald (2005). "John Muir and the Modern Passion for Nature". Environmental History. 10(1): 8–19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Worster, Donald (2008). A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195166828.

- Wuerthner, George (1994). Yosemite: A Visitor's Companion. Stackpole Books. pp. 25–37. ISBN 0-8117-2598-7.

- Yancey, Philip (2004). Rumours of Another World: What on Earth Are We Missing? (PDF). Zondervan Publishing Company.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "p. 24-25" ignored (help)

External links

- Works by or about John Muir at Internet Archive (scanned books original editions color illustrated)

- Works by John Muir at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML)

- Template:Worldcat id

- John Muir Writings. Complete text online of Muir's books

- John Muir's Correspondence, 1856-1914, online archive

- Manuscript letters, 1861-1914 put online by the Wisconsin Historical Society

- John Muir's Clockwork Desk, Wisconsin Historical Society exhibit.

- John Muir Papers. Provides an overview of the John Muir Papers and related collections held at the University of the Pacific.

- John Muir Exhibit by the Sierra Club; includes a detailed chronology.

- John Muir Global Network

- John Muir National Historic Site from National Park Service

- Friends of John Muir's Birthplace (formerly Dunbar's John Muir Association) Scotland

- John Muir's Birthplace, John Muir Birthplace Trust Scotland

- John Muir Trust Scotland

- Canadian Friends of John Muir (CFJM) website

- John Muir Project Protecting Federal Public Forest Lands

- Access Adventure Founded by Muir's grandson

- 9 short radio episodes California Glaciers, Earthquake, Samoset, Two Pine Logs, The Water-Ouzel, Wild Bees of California, The Wind, A Windstorm in the Forest and Woody Gospel Letter based on the writings of John Muir. California Legacy Project.

- American conservationists

- American essayists

- American explorers

- American geologists

- American mountain climbers

- American naturalists

- American nature writers

- Sierra Nevada

- Yosemite National Park

- Writers who illustrated their own writing

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- California activists

- Writers from California

- Scottish immigrants to the United States

- Scottish Americans

- Martinez, California

- People from Dunbar

- People from East Lothian

- Hetch Hetchy Project

- 1838 births

- 1914 deaths