Watergate scandal

| Watergate scandal |

|---|

|

| Events |

| People |

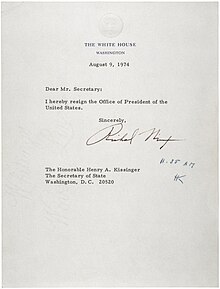

The Watergate scandal was a political scandal in the United States in the 1970s, resulting from the break-in into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C. Effects of the scandal ultimately led to the resignation of the United States President Richard Nixon on August 9, 1974. It also resulted in the indictment and conviction of several Nixon administration officials.

The scandal began with the arrest of five men for breaking and entering into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex on June 17, 1972. The subsequent investigation by the FBI connected the men to the 1972 Committee to Re-elect the President by a slush fund.[1] [2] As evidence mounted against the president's staff, which included former staff members testifying against them in an investigation conducted by the Senate Watergate Committee, it was revealed that President Nixon had a tape recording system in his offices and that he had recorded many conversations.[3][4] Recordings from these tapes implicated the president, revealing that he had attempted to cover up the break-in.[2][5] After a series of court battles, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the president had to hand over the tapes; he ultimately complied.

Facing near-certain impeachment in the House of Representatives and a strong possibility of a conviction in the Senate, Nixon resigned the office of the presidency on August 9, 1974.[6][7] His successor, Gerald Ford, issued a pardon to President Nixon after his resignation.

Break-in

On the evening of June 17, 1972, Frank Wills, a security guard at the Watergate Complex, noticed tape covering the latch on locks on several doors in the complex (leaving the doors unlocked). He took the tape off, and thought nothing of it. An hour later, he discovered that someone had retaped the locks. Wills called the police and five men were arrested inside the Democratic National Committee's (DNC) office.[8] The five men were Virgilio González, Bernard Barker, James W. McCord, Jr., Eugenio Martínez, and Frank Sturgis. The five were charged with attempted burglary and attempted interception of telephone and other communications. On September 15, a grand jury indicted them and two other men (E. Howard Hunt, Jr. and G. Gordon Liddy[1]) for conspiracy, burglary, and violation of federal wiretapping laws.

The men who broke into the office were tried and convicted on January 30, 1973. After much investigation, all five men were directly or indirectly tied to the 1972 Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP, or sometimes pejoratively referred to as CREEP) and the trial judge, John J. Sirica, suspected a conspiracy involving higher-echelon government officials.[9] In March 1973, James McCord wrote a letter to Sirica, claiming that he was under political pressure to plead guilty and he implicated high-ranking government officials, including former Attorney General John Mitchell.[10] His letter helped to elevate the affair into a more prominent political scandal.[11]

Investigation

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2009) |

The unraveling of the coverup began in the immediate aftermath of the arrests, the search of the burglars' hotel rooms, and a background investigation of the initial evidence, most prominently thousands of dollars in cash in their possession at the time of arrest. On June 19, 1972 it was publicly revealed that one of the Watergate burglars was a GOP security aide. Former Attorney General John Mitchell, who at the time was the head of the Nixon re-election campaign, denied any involvement with the Watergate break-in or knowing the five burglars. On August 1, a $25,000 cashiers check earmarked for the Nixon re-election campaign, was found in the bank account of one of the Watergate burglars. Further investigation would reveal accounts showing that still more thousands had passed through their bank and credit card accounts, supporting their travel, living expenses, and purchases, in the months leading up to their arrests. Examination of the burglars' accounts showed the link to the 1972 Committee to Re-Elect the President, through its subordinate finance committee.

Several individual donations (totaling $89,000) were made by individuals who thought they were making private donations to the President's re-election committee. The donations were made in the form of cashier's, certified, and personal checks, and all were made payable only to the Committee to Re-Elect the President. Investigative examination of the bank records of a Miami company run by Watergate burglar Bernard Barker revealed that an account controlled by him personally had deposited, and had transferred to it (through the Federal Reserve Check Clearing System) the funds from these financial instruments.

The banks that had originated the checks (especially the certified and cashier's checks) were keen to ensure that the depository institution used by Bernard Barker had acted properly to protect their (the correspondent banks') fiduciary interest in ensuring that the checks had been properly received and endorsed by the check’s payee, prior to its acceptance for deposit in Bernard Barker's account. Only in this way would the correspondent banks, which had issued the checks on behalf of the individual donors, not be held liable for the un-authorized and improper release of funds from their customer’s accounts into the account of Bernard Barker.

The investigative finding, which cleared Bernard Barker’s bank of fiduciary malfeasance, led to the direct implication of members of the Committee to Re-Elect the President, to whom the checks had been delivered. Those individuals were the Committee Bookkeeper and its Treasurer, Hugh Sloan.

The Committee, as an organization, followed normal business accounting standards in allowing only duly authorized individual(s) to accept and endorse on behalf of the Committee any financial instrument created on the Committee’s behalf by itself, or by others. Therefore, no financial institution would accept or process a check on behalf of the Committee unless it had been endorsed and verified as endorsed by a duly authorized individual(s). On the checks themselves deposited into Bernard Barker’s bank account was the endorsement of Committee Treasurer Hugh Sloan who was duly authorized and designated to endorse such instruments that were prepared (by others) on behalf of the Committee.

But once Sloan had endorsed a check made payable to the Committee, he had a legal and fiduciary responsibility to see that the check was deposited into the account(s) which were named on the check, and for which he had been delegated fiduciary responsibility. Sloan failed to do that. He was confronted and faced the potential charge of federal bank fraud; he revealed that he had given the checks to G. Gordon Liddy and was directed by Committee Deputy Director Jeb Magruder and Finance Director Maurice Stans to do so.

On September 29, 1972 it was revealed that John Mitchell, while serving as Attorney General, controlled a secret Republican fund used to finance intelligence-gathering against the Democrats. On October 10, the FBI reported that the Watergate break-in was part of a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage on behalf of the officials and heads of the Nixon re-election campaign. Despite these revelations, Nixon's re-election campaign was never seriously jeopardized, and on November 7 the President was re-elected in one of the biggest landslides ever in American political history.

Barker had been given the checks by Liddy in an attempt to avoid direct proof that Barker ever had received funds from the organization. Barker had attempted to disguise the origin of the funds by depositing the donor’s checks into bank accounts which (though controlled by him), were located in banks outside of the United States. What Barker, Liddy, and Sloan did not know was that the complete record of all such transactions are held, after the funds cleared, for roughly six months. Barker’s use of foreign banks to deposit checks and withdraw the funds via cashier’s checks and money orders in April and May 1972 guaranteed that the banks would keep the entire transaction record at least until October and November 1972.

The connection between the break-in and the re-election campaign committee was highlighted by media coverage. In particular, investigative coverage by Time, The New York Times, and especially The Washington Post, fueled focus on the event. The coverage dramatically increased publicity and consequent political repercussions. Relying heavily upon anonymous sources, Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered information suggesting that knowledge of the break-in, and attempts to cover it up, led deep into the Justice Department, the FBI, the CIA, and even the White House. Chief among the Post's anonymous sources was an individual they had nicknamed Deep Throat (who was much later revealed in 2005 to be former Deputy Director of the FBI William Mark Felt, Sr.) It was Deep Throat who met secretly with Woodward, and told him of Howard Hunt’s involvement with the Watergate break-in, and that the rest of the White House staff regarded the stake in Watergate extremely high. Deep Throat also warned Woodward that the FBI wanted to know where he and the other reporters were getting the information which was uncovering even a wider web of crimes than first disclosed. In one of their last meetings, all of which took place at an underground parking garage somewhere in Washington DC at 2:00 AM, Deep Throat cautioned Woodward that he might be followed and not to trust their phone conversations.

Rather than ending with the trial and conviction of the burglars, the investigations grew broader; a Senate committee chaired by Senator Sam Ervin was set up to examine Watergate and began issuing subpoenas to White House staff members.

On April 30, 1973, Nixon was forced to ask for the resignation of two of his most influential aides, H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, both of whom were indicted and ultimately went to prison. He also fired White House Counsel John Dean, who went on to testify before the Senate and become the key witness against President Nixon.

The President announced these resignations in an address to the American people:

"In one of the most difficult decisions of my Presidency, I accepted the resignations of two of my closest associates in the White House, Bob Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, two of the finest public servants it has been my privilege to know. Because Attorney General Kleindienst, though a distinguished public servant, my personal friend for 20 years, with no personal involvement whatever in this matter has been a close personal and professional associate of some of those who are involved in this case, he and I both felt that it was also necessary to name a new Attorney General. The Counsel to the President, John Dean, has also resigned."[12]

— Richard Nixon

On the same day, Nixon appointed a new Attorney General, Elliot Richardson, and gave him authority to designate, for the Watergate inquiry, a special counsel who would be independent of the regular Justice Department hierarchy. In May 1973, Richardson named Archibald Cox to the position. This is complete bullshit

Tapes

The hearings held by the Senate Committee, in which Dean and other former administration officials delivered testimony, were broadcast from May 17 to August 7, 1973, causing political damage to the President. After the three major networks of the time agreed to take turns covering the hearings live (the first 24-hour news channel was not introduced until 1980), each network thus maintained coverage of the hearings every third day, starting with ABC on May 17 and ending with NBC on August 7. An estimated 85% of Americans with television sets tuned in to at least one portion of the hearings.[13]

On July 13, 1973, Donald Sanders, the Deputy Minority Counsel, asked Alexander Butterfield if there was any type of recording systems in the White House.[14] Butterfield answered that, though he was reluctant to say so, there was a system in the White House that automatically recorded everything in the Oval Office and other rooms in the White House, including the Cabinet Room and Nixon's private office in the Old Executive Office Building. Later, Chief Minority Counsel Fred Thompson asked Butterfield if he was "aware of the installation of any listening devices in the Oval Office of the president?" The shocking revelation transformed the Watergate investigation yet again. The tapes were soon subpoenaed by prosecutor Cox and then by the Senate. Nixon refused to release them, citing his executive privilege as President of the United States, and ordered Cox to drop his subpoena. Cox refused.[15]

A taped conversation that was crucial to the case against President Nixon [16] took place between the President and his counsel, John Dean, on March 21, 1973. In this conversation, Dean summarizes many aspects of the Watergate case, and then focuses on the subsequent coverup, describing it as a "cancer on the presidency". The burglary team was being paid hush money for their silence and Dean states: "that's the most troublesome post-thing, because Bob [Haldeman] is involved in that; John [Ehrlichman] is involved in that; I am involved in that; Mitchell is involved in that. And that's an obstruction of justice." [17] Dean continues and states that Howard Hunt is blackmailing the White House, demanding money immediately, and President Nixon states that the blackmail money should be paid: "...just looking at the immediate problem, don't you have to have -- handle Hunt's financial situation damn soon? [...] you've got to keep the cap on the bottle that much, in order to have any options." [17] At the time of the initial congressional impeachment debate on Watergate, it was not known that Nixon had known and approved of the payments to the Watergate defendants much earlier than this conversation. Among later released recordings, Nixon's conversation with Haldeman on August 1, 1972 is one of several tapes that establishes this. Nixon states: "Well...they have to be paid. That's all there is to that. They have to be paid" [18] During congressional debate on impeachment, those who believed that impeachment required a criminally indictable offense focused their attention on President Nixon's agreement to make the blackmail payments, regarding this as an affirmative act to obstruct justice as a member of the cover-up conspiracy.[19]

"Saturday Night Massacre"

Cox's refusal to drop his subpoena influenced Nixon to demand the resignations of Richardson and deputy William Ruckelshaus, on October 20, 1973, in a search of someone in the Justice Department willing to fire Cox. This search ended with Solicitor General Robert Bork. Though Bork believed Nixon's order to be valid and appropriate, he considered resigning to avoid being "perceived as a man who did the President's bidding to save my job."[20] However, both Richardson and Ruckelshaus persuaded him not to resign, in order to prevent any further damage to the Justice Department. As the new acting department head, Bork carried out the presidential order and dismissed the special prosecutor. Allegations of wrongdoing prompted Nixon to famously state "I'm not a crook" in front of 400 Associated Press managing editors on November 17, 1973.[21][22]

Nixon was forced, however, to allow the appointment of a new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, who continued the investigation. While Nixon continued to refuse to turn over actual tapes, he agreed to release transcripts of a large number of them; Nixon cited the fact that any audio pertinent to national security information could be redacted from the released tapes.

The audio tapes caused further controversy on December 7, when an 18½ minute portion of one tape was found to have been erased. Nixon's personal secretary, Rose Mary Woods, said she had accidentally erased the tape by pushing the wrong foot pedal on her tape player while answering the phone. However, as photos all over the press showed, it was unlikely for Woods to answer the phone and keep her foot on the pedal. Later forensic analysis determined that the tape had been erased in several segments — at least five, and perhaps as many as nine.[23]

Supreme Court

The issue of access to the tapes went to the Supreme Court. On July 24, 1974, in United States v. Nixon, the Court, which did not include the recused Justice William Rehnquist, ruled unanimously that claims of executive privilege over the tapes were void, and they ordered the president to give them to the special prosecutor. On July 30, 1974, President Nixon complied with the order and released the subpoenaed tapes.

Final investigations and resignation

On March 1, 1974, former aides to the president, known as the "Watergate Seven" — Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Mitchell, Charles Colson, Gordon C. Strachan, Robert Mardian and Kenneth Parkinson — were indicted for conspiring to hinder the Watergate investigation. The grand jury also secretly named Nixon as an unindicted co-conspirator. John Dean, Jeb Stuart Magruder, and other figures had already pleaded guilty. On April 5, 1974, former Nixon appointments secretary Dwight Chapin was convicted of lying to the grand jury. Two days later, the Watergate grand jury indicted Ed Reinecke, Republican lieutenant governor of California, on three charges of perjury before the Senate committee.

Nixon's position was becoming increasingly precarious, and the House of Representatives began formal investigations into the possible impeachment of the president. The House Judiciary Committee voted 27 to 11 on July 27, 1974 to recommend the first article of impeachment against the president: obstruction of justice. The second (abuse of power) and third (contempt of Congress) articles were passed on July 29, 1974 and July 30, 1974, respectively.

The "Smoking Gun" tape

On August 3, 1974, the previously unknown audio tape from June 23, 1972, was released. Recorded only a few days after the break-in, it documented Nixon and Haldeman meeting in the Oval Office and formulating a plan to block investigations by having the CIA falsely claim to the FBI that national security was involved. Haldeman introduces the topic as follows: "...the Democratic break-in thing, we're back to the--in the, the problem area because the FBI is not under control, because Gray doesn't exactly know how to control them, and they have... their investigation is now leading into some productive areas [...] and it goes in some directions we don't want it to go." After explaining how the money from CRP was traced to the burglars, Haldeman explained to Nixon the coverup plan: "the way to handle this now is for us to have Walters [CIA] call Pat Gray [FBI] and just say, 'Stay the hell out of this ...this is ah, business here we don't want you to go any further on it.'" President Nixon approved the plan, and he is given more information about the involvement of his campaign in the break-in, telling Haldeman: "All right, fine, I understand it all. We won't second-guess Mitchell and the rest." Returning to the use of the CIA to obstruct the FBI, he instructs Haldeman: "You call them in. Good. Good deal. Play it tough. That's the way they play it and that's the way we are going to play it." [24]

Prior to the release of this tape, President Nixon had denied political motivations in his instructions to the CIA, and claimed he had no knowledge prior to March 21, 1973 of any involvement by senior campaign officials such as John Mitchell. The contents of this tape persuaded President Nixon's own lawyers, Fred Buzhardt and James St. Clair, "The tape proved that the President had lied to the nation, to his closest aides, and to his own lawyers - for more than two years." [25] The tape, which was referred to as a "smoking gun," hampered Nixon politically. The ten congressmen who had voted against all three articles of impeachment in the committee announced that they would all support impeachment when the vote was taken in the full House.

Resignation

Throughout this time, Nixon still denied any involvement in the ordeal. However, after being told by key Republican Senators that enough votes existed to remove him, Nixon decided to resign. In a nationally televised address from the Oval Office on the evening of August 8, 1974, the president said,

In all the decisions I have made in my public life, I have always tried to do what was best for the Nation. Throughout the long and difficult period of Watergate, I have felt it was my duty to persevere, to make every possible effort to complete the term of office to which you elected me. In the past few days, however, it has become evident to me that I no longer have a strong enough political base in the Congress to justify continuing that effort. As long as there was such a base, I felt strongly that it was necessary to see the constitutional process through to its conclusion, that to do otherwise would be unfaithful to the spirit of that deliberately difficult process and a dangerously destabilizing precedent for the future....

I would have preferred to carry through to the finish whatever the personal agony it would have involved, and my family unanimously urged me to do so. But the interest of the Nation must always come before any personal considerations. From the discussions I have had with Congressional and other leaders, I have concluded that because of the Watergate matter I might not have the support of the Congress that I would consider necessary to back the very difficult decisions and carry out the duties of this office in the way the interests of the Nation would require.

I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But as President, I must put the interest of America first. America needs a full-time President and a full-time Congress, particularly at this time with problems we face at home and abroad. To continue to fight through the months ahead for my personal vindication would almost totally absorb the time and attention of both the President and the Congress in a period when our entire focus should be on the great issues of peace abroad and prosperity without inflation at home. Therefore, I shall resign the Presidency effective at noon tomorrow. Vice President Ford will be sworn in as President at that hour in this office.[26]

The morning that his resignation was to take effect, President and Mrs. Nixon and their family bade farewell to the White House staff in the East Room.[28] A helicopter took him from the White House to Andrews Air Force base in Maryland. Nixon later wrote that he remembered thinking "As the helicopter moved on to Andrews, I found myself thinking not of the past, but of the future. What could I do now?..." At Andrews, he boarded Air Force One to El Toro Marine Corps Air Station in California and then to his home in San Clemente.

Pardon and aftermath

Though President Nixon's resignation prompted Congress to drop the impeachment proceedings, criminal prosecution was still a possibility. Nixon was succeeded by Vice President Gerald Ford, who on September 8, 1974, issued a full and unconditional pardon unto President Nixon, immunizing him from prosecution for any crimes he had "committed or may have committed or taken part in" as President.[29] In a televised broadcast to the nation, Ford explained that he felt the pardon was in the best interest of the country and that the Nixon family's situation "is an American tragedy in which we all have played a part. It could go on and on and on, or someone must write the end to it. I have concluded that only I can do that, and if I can, I must."[30]

Nixon proclaimed his innocence until his death in 1994. He did state in his official response to the pardon that he "was wrong in not acting more decisively and more forthrightly in dealing with Watergate, particularly when it reached the stage of judicial proceedings and grew from a political scandal into a national tragedy."

The Nixon pardon has been argued to be a factor in President Ford's loss of the presidential election of 1976.[31] Accusations of a secret "deal" made with Ford, promising a pardon in return for Nixon's resignation, led Ford to testify before the House Judiciary Committee on October 17, 1974.[32][33]

In his autobiography A Time to Heal, Ford wrote about a meeting he had with Nixon's Chief of Staff, Alexander Haig. Haig was explaining what he and Nixon's staff thought were Nixon's only options. He could try to ride out the impeachment and fight against conviction in the Senate all the way, or he could resign. His options for resigning were to delay his resignation until further along in the impeachment process to try and settle for a censure vote in Congress, or pardon himself and then resign. Haig then told Ford that some of Nixon's staff suggested that Nixon could agree to resign in return for an agreement that Ford would pardon him.

Haig emphasized that these weren't his suggestions. He didn't identify the staff members and he made it very clear that he wasn't recommending any one option over another. What he wanted to know was whether or not my overall assessment of the situation agreed with his.[emphasis in original]. . . Next he asked if I had any suggestions as to courses of actions for the President. I didn't think it would be proper for me to make any recommendations at all, and I told him so.[34]

Charles Colson pleaded guilty to charges concerning the Daniel Ellsberg case; in exchange, the indictment against him for covering up the activities of the Committee to Re-elect the President was dropped, as it was against Strachan. The remaining five members of the Watergate Seven indicted in March went on trial in October 1974, and on January 1, 1975, all but Parkinson were found guilty. In 1976, the U.S. Court of Appeals ordered a new trial for Mardian; subsequently, all charges against him were dropped. Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and Mitchell exhausted their appeals in 1977. Ehrlichman entered prison in 1976, followed by the other two in 1977.

The effect on the upcoming Senate election and House race, only three months later, was significant. The Democrats gained five seats in the Senate and 49 in the House. Watergate was also indirectly responsible for changes in campaign financing. It was a driving factor in amending the Freedom of Information Act in 1974, as well as laws requiring new financial disclosures by key government officials, such as the Ethics in Government Act. While not legally required, other types of personal disclosure, such as releasing recent income tax forms, became expected. Presidents since Franklin D. Roosevelt had recorded many of their conversations, but after Watergate this practice purportedly ended.

Also, Congress investigated the scope of the President's actual legal powers, and belatedly realized that the United States had been in a continuous open-ended state of emergency since 1950, which led to the enactment of the National Emergencies Act in 1976.

The Watergate scandal left such an impression on the national and international consciousness that many scandals since then have been labeled with the suffix "-gate".

According to Thomas J. Johnson, professor of journalism at Southern Illinois University, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger boldly predicted during Nixon's final days that history would remember Nixon as a great president and that Watergate would be relegated to a "minor footnote." [35]

Since Nixon and many senior officials involved in Watergate were lawyers, the scandal severely tarnished the public image of the legal profession.[36][37][38] In order to defuse public demand for direct federal regulation of lawyers (as opposed to leaving it in the hands of state bar associations or courts), the American Bar Association (ABA) launched two major reforms. First, the ABA decided that its existing Model Code of Professional Responsibility (promulgated 1969) was a failure and replaced it with the Model Rules of Professional Conduct in 1983.[39] The MRPC have been adopted in part or in whole by 48 states. Its preamble contains an emphatic reminder to young lawyers that the legal profession can remain self-governing only if lawyers behave properly. Second, the ABA promulgated a requirement that law students at ABA-approved law schools take a course in professional responsibility (which means they must study the MRPC). The requirement remains in effect.

Purpose of the break-in

Despite an enormous impact of the Watergate scandal, the actual purpose of the break-in of the DNC offices has never been conclusively established. Some theories suggest that the burglars were after specific information. The likeliest of these theories suggests that the target of the break-in was the offices of Larry O'Brien, the Chairman of the DNC [40]. In 1968, O'Brien was appointed by Vice President Hubert Humphrey to serve nationally as the director of his presidential campaign and by Howard Hughes to serve in Washington as his public-policy lobbyist. O'Brien was elected in 1968 and 1970 by the DNC to serve nationally as its chairman. With the upcoming Presidential election, former Howard Hughes business associate John H. Meier, working with Hubert Humphrey and others, wanted to feed misinformation to Richard Nixon. John Meier's father had been a German agent during World War II. Meier had joined the FBI and in the 60s had contracted to the CIA to eliminate Fidel Castro using Mafia bosses Sam Giancana and Santo Trafficante.[41] In late 1971, the President’s brother, Donald Nixon, was collecting intelligence for his brother at the time and was asking Meier about Larry O'Brien. In 1956, Donald Nixon had borrowed $205,000 from Howard Hughes and never repaid the loan. The fact of the loan surfaced during the 1960 presidential election campaign embarrassing Richard Nixon and becoming a real political liability. According to author Donald M. Bartlett, Richard Nixon would do all that would be necessary to prevent another Hughes-Nixon family embarrassment.[42] From 1968 to 1970, Hughes withdrew nearly half a million dollars from the Texas National Bank of Commerce for contributions to both Democrats and Republicans, including presidential candidates Humphrey and Nixon. Hughes wanted Donald Nixon and Meier involved but Richard Nixon was opposed to their involvement.[43]

Meier told Donald that he was sure the Democrats would win the election because they had considerable information on Richard Nixon’s illicit dealings with Howard Hughes that had never been released, and that Larry O’Brien had the information,[44] (O’Brien who had received $25,000 from Hughes didn’t actually have any documents but Meier claims to have wanted Richard Nixon to think he did). It is only a question of conjecture then that Donald called his brother Richard and told him that Meier gave the Democrats all the Hughes information that could destroy him and that O’Brien had the proof.[45] The fact is Larry O'Brien, elected Democratic Party Chairman, was also a lobbyist for Howard Hughes in a Democratic controlled Congress and the possibility of his finding about Hughes illegal contributions to the Nixon campaign was too much of a danger for Nixon to ignore and O'Brien's office at Watergate became a target of Nixon's intelligence in the political campaign.[46] This theory has been proposed as a motivation for the break-in.

Numerous theories have persisted in claiming deeper significance to the Watergate scandal than that commonly acknowledged by media and historians:

- In the book The Ends of Power, Nixon's chief of staff H. R. Haldeman claimed that the term "Bay of Pigs", mentioned by Nixon in a tape-recorded White House conversation as the reason the CIA should put a stop to the Watergate investigations,[2] was used by Nixon as a coded reference to a CIA plot to assassinate Fidel Castro during the John F. Kennedy administration. The CIA had not disclosed this plot to the Warren Commission, the commission investigating the Kennedy assassination, despite the fact that it would attribute a motive to Castro in the assassination.[47] Any such revelation would also expose CIA/Mafia connections that could lead to unwanted scrutiny of suspected CIA/Mafia participants in the assassination of the president. Furthermore, Nixon's awareness as vice-president of the Bay of Pigs plan and his own ties to the underworld and unsavory intelligence operations might come to light. A theoretical connection between the Kennedy assassination and the Watergate Tapes was later referred to in the biopic, Nixon, directed by Oliver Stone.

- Silent Coup, a 1991 book by Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin, argued that it was Nixon's silent war with the Pentagon that ultimately led to his removal from office.[32]

The book was criticized for apparent leaps of logic and the citation of weak evidence and its theories are not widely supported by either professional historians or the general public.[48][49]

- Secret Honor by Stone and Freed[who?] implies that Nixon deliberately sacrificed his presidency to save democracy from a plan to implement martial law. The theory uses the construct of "Yankees" vs. "Cowboys" to suggest that, since the postwar era, the United States has been dominated by Yankees competing with Cowboys. Nixon, who hailed from the Southwest, was initially backed by the military industrial defense contractor power-brokers (the Cowboys); however, he later wanted to jump ship and return government to the east-coast establishment of Yankees. His resignation accomplished this because Nelson Rockefeller, the epitome of the eastern economic elite, assumed the vice presidency after Nixon's resignation.

- Peter Beter's Conspiracy Against the Dollar further explains how Nixon was possibly a rogue liberal with a conservative mask.

- Andreas Killen's 1973 nervous breakdown mentions this obscure theory behind Watergate.[citation needed]

- Gordon Novel, a man known for several controversial investigations, has claimed Watergate served as a discourse to stop the Nixon administration to hold Senate hearings about a postmortem on the Vietnam war.[50]

- Political scientist George Friedman argued that: "The Washington Post created a morality play about an out-of-control government brought to heel by two young, enterprising journalists and a courageous newspaper. That simply wasn't what happened. Instead, it was about the FBI using The Washington Post to leak information to destroy the president, and The Washington Post willingly serving as the conduit for that information while withholding an essential dimension of the story by concealing Deep Throat's identity" and that FBI under the direction of Mark Felt must have began spying on the white house before the watergate break-in.[51]

- MIT professor Noam Chomsky argued that it was Nixon's dismantling of the Bretton Woods system that made him an enemy of multinational corporations and international bankers.[52]

References

- ^ a b

Dickinson, William B. (1973). Watergate: chronology of a crisis. Vol. 1. Washington D. C.: Congressional Quarterly Inc. pp. 8 133 140 180 188. ISBN 0871870592. OCLC 20974031.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) This book is volume 1 of a two volume set. Both volumes share the same ISBN and Library of Congress call number, E859 .C62 1973 Cite error: The named reference "congressional quarterly vol 1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c "The Smoking Gun Tape" (Transcript of the recording of a meeting between President Nixon and H. R. Haldeman). Watergate.info website. June 23, 1972. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^

narrative by R.W. Apple, jr. ; chronology by Linda Amster ; general ed.: Gerald Gold. (1973). The Watergate hearings: break-in and cover-up; proceedings. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0670751529.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nixon, Richard (1974). The White House Transcripts. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0670763241. OCLC 1095702.

- ^ The evidence was quite simple: there was the voice of the President on June 23, 1972, directing the CIA to halt an FBI investigation which would be politically embarrassing to his re-election, which was an obstruction of justice. White, Theodore Harold (1975). Breach of faith: the fall of Richard Nixon. New York: Atheneum Publishers. p. 7. ISBN 0689106580.

- ^ "And the most punishing blow of all was yet to come in late afternoon when the President received, in his Oval Office, the Congressional leaders of his party — Barry Goldwater, Hugh Scott, John Rhodes. The accounts of all three coincide... Goldwater averred that there were not more than fifteen votes left in his support in the Senate...." White, Theodore Harold (1975). Breach of faith: the fall of Richard Nixon. New York: Atheneum Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 0689106580.

- ^ "Soon Alexander Haig and James St. Clair learned of the existence of this tape and they were convinced that it would guarantee Nixon's impeachment in the House of Representatives and conviction in the Senate." Dash, Samuel (1976). Chief counsel: inside the Ervin Committee — the untold story of Watergate. New York: Random House. pp. 259–260. ISBN 0-394-40853-5.

- ^ Sirica, John J. (1979). To set the record straight: the break-in, the tapes, the conspirators, the pardon. New York: Norton. p. 44. ISBN 0-393-01234-4.

- ^ "There were still simply too many unanswered questions in the case. By that time, thinking about the break-in and reading about it, I'd have had to be some kind of moron to believe that no other people were involved. No political campaign committee would turn over so much money to a man like Gordon Liddy without someone higher up in the organization approving the transaction. How could I not see that? These questions about the case were on my mind during a pretrial session in my courtroom December 4." Sirica, John J. (1979). To set the record straight: the break-in, the tapes, the conspirators, the pardon. New York: Norton. p. 56. ISBN 0-393-01234-4.

- ^ http://www.upi.com/Audio/Year_in_Review/Events-of-1973/Watergate-Scandal/12305770297723-4/ "Watergate Scandal, 1973 In Review."

- ^ "When Judge Sirica finished reading the letter, the courtroom exploded with excitement and reporters ran to the rear entrance to phone their newspapers. The bailiff kept banging for silence. It was a stunning development, exactly what I had been waiting for. Perjury at the trial. The involvement of others. It looked as if Watergate was about to break wide open." Dash, Samuel (1976). Chief counsel: inside the Ervin Committee--the untold story of Watergate. New York: Random House. p. 30. ISBN 0-394-40853-5.

- ^ http://www.upi.com/Audio/Year_in_Review/Events-of-1973/Watergate-Scandal/12305770297723-4/ "Watergate Scandal, 1973 in Review"

- ^ Garay, Ronald. "Watergate". The Museum of Broadcast Communication. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Kranish, Michael (2007-07-04). "Select Chronology for Donald G. Sanders". The Boston Globe.

- ^ http://www.upi.com/Audio/Year_in_Review/Events-of-1973/Watergate-Scandal/12305770297723-4/ "Watergate Scandal, 1973 In Review"

- ^ Kutler, S: Abuse of Power, page 247. Simon & Schuster, 1997.

- ^ a b http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/forresearchers/find/tapes/watergate/wspf/886-008.pdf "TRANSCRIPT PREPARED BY THE IMPEACHMENT INQUIRY STAFF FOR THE HOUSE JUDICIARY COMMITTEE OF A RECORDING OF A MEETING AMONG THE PRESIDENT, JOHN DEAN AND H.R. HALDEMAN ON MARCH 21, 1973 FROM 10:12 TO 11:55 A.M."

- ^ Kutler, S: Abuse of Power, page 111. Simon & Schuster, 1997. Transcribed conversation between President Nixon and Haldeman.

- ^ Bernstein, C. and Woodward, B: The Final Days, page 252. Simon & Schuster, 1976.

- ^ Noble, Kenneth (1987-07-02). "Bork Irked by Emphasis on His Role in Watergate". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ Richard Nixon: Question-and-Answer Session at the Annual Convention of the Associated Press Managing Editors Association, Orlando, Florida. The American Presidency Project.

- ^ Kilpatrick, Carroll, Nixon Tells Editors, 'I'm Not a Crook' Washington Post, November 18, 1973.

- ^ Clymer, Adam (May 9, 2003). "National Archives Has Given Up on Filling the Nixon Tape Gap". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/forresearchers/find/tapes/watergate/wspf/741-002.pdf "TRANSCRIPT OF A RECORDING OF A MEETING BETWEEN THE PRESIDENT AND H.R. HALDEMAN IN THE OVAL OFFICE ON JUNE 23, 1972 FROM 10:04 TO 11:39 AM" Watergate Special Prosecution Force

- ^ Bernstein, C. and Woodward, B: The Final Days, page 309. Simon & Schuster, 1976.

- ^ "President Nixon's Resignation Speech". PBS. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ^ Lucas, Dean. "Famous Pictures Magazine - Nixon's V sign". Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ Brokaw, Tom (August 6, 2004). "Politicians come and go, but rule of law endures". MSNBC. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ^ http://www.ford.utexas.edu/LIBRARY/speeches/740061.htm

- ^ Ford, Gerald (1974-09-08). "Gerald R. Ford Pardoning Richard Nixon". Great Speeches Collection. The History Place. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Shane, Scott. "For Ford, Pardon Decision Was Always Clear-Cut". The New York Times. p. A1.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Gettlin, Robert; Colodny, Len (1991). Silent coup: the removal of a president. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 420. ISBN 0312051565. OCLC 22493143.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ford, Gerald R. (1979). A time to heal: the autobiography of Gerald R. Ford. San Francisco: Harper & Row. pp. 196–199. ISBN 0060112972.

- ^ Ford (1979), 4.

- ^ Thomas J. Johnson, Watergate and the Resignation of Richard Nixon: Impact of a Constitutional Crisis, "The Rehabilitation of Richard Nixon", eds. P. Jeffrey and Thomas Maxwell-Long: Washington, D.C., CQ Press, 2004, pp. 148-149.

- ^ Anita L. Allen, The New Ethics: A Tour of the 21st Century Landscape (New York: Miramax Books, 2004), 101.

- ^ Thomas L. Shaffer & Mary M. Shaffer, American Lawyers and Their Communities: Ethics in the Legal Profession (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991), 1.

- ^ Jerold Auerbach, Unequal Justice: Lawyers and Social Change in Modern America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), 301.

- ^ Theodore Schneyer, "Professionalism as Politics: The Making of a Modern Legal Ethics Code," in Lawyers' Ideals/Lawyers' Practices: Transformations in the American Legal Profession, eds. Robert L. Nelson, David M. Trubek, & Rayman L. Solomon, 95-143 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992), 104.

- ^ Greenberg, David (2005-06-05). "The Unsolved Mysteries of Watergate". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Rachel Verdon Murder by Madness 9/11, p. 145, Rachel Verdon, 2007 ISBN 978-1419680229

- ^ Donald L. Bartlett Howard Hughes, p. 410, W. W. Norton & Co., 2004 ISBN 978-0393326024

- ^ Charles Higham Howard Hughes, p. 244, Macmillan, 2004 ISBN 978-0312329976

- ^ DuBois, Larry, and Laurence Gonzales (September 1976). Hughes Nixon and the C.I.A.: The Watergate Conspiracy Woodward and Bernstein Missed. Playboy.

- ^ Age of Secrets

- ^ Fred Emery Watergate, p. 30, Simon & Schuster, 1995 ISBN 978-0684813233

- ^

DiMona, Joseph; Haldeman, H. R. (1978). The ends of power. New York: Times Books. ISBN 0812907248. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Who is Deep Throat? Does It Matter?". Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ^ "Was Nixon duped? Did Woodward lie?". Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ^ Bill Ryan, Kerry Cassidy (December 2006). "Project Camelot - Renegade: Gordon Novel on Camera" (Video and Transcript). Los Angeles. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ http://www.mercatornet.com/articles/view/the_deeper_truth_about_deep_throat/

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (2002) Understanding Power

Further reading

- Doyle, James (1977). Not Above the Law: the battles of Watergate prosecutors Cox and Jaworski. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-03192-7.

- Schudson, Michael (1992). Watergate in American memory: how we remember, forget, and reconstruct the past. New York: BasicBooks. ISBN 0465090842.

- White, Theodore Harold (1975). Breach of faith: the fall of Richard Nixon. New York: Atheneum Publishers. ISBN 0689106580. A comprehensive history of the Watergate Scandal by Teddy White, a respected journalist and author of the The Making of the President series.

- Woodward, Bob and Bernstein, Carl wrote a best-selling book based on their experiences covering the Watergate Scandal for the Washington Post titled All the President's Men, published in 1974. A film adaptation, starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman as Woodward and Bernstein, respectively, was released in 1976.

- Woodward, Bob; Bernstein, Carl (2005). The Final Days. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-7406-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - contains further details from March 1973 through September 1974.

External links

- White House tape transcripts

- The White House tapes themselves

- nixontapes.org

- Washington Post Watergate Archive

- Washington Post Watergate Tape Listening Guide

- BBC News reports on Watergate

- Watergate Timeline

- Watergate Key Players

- Extensive set of online Watergate

- Biography of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein