Comparison of digital and film photography

This article possibly contains original research. (October 2007) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

Digital versus film photography is a topic sometimes debated by photographers. Both digital and film have advantages and drawbacks. [1][2]

Image quality

Spatial resolution

The quality of digital photographs an be measured in several ways. Pixel count is presumed to correlate with spatial resolution.[3] The quantity of picture elements (pixels) in the image sensor is usually counted in millions and called "megapixels". The resolution of film images depends upon the area of film used to record the image - 35 mm, Medium format or Large format - the speed of the film and the quality of lens fitted to the camera.

Digital cameras have a variable relationship between resolution and megapixel count;[4] other factors are important in digital camera resolution, such as the number of pixels used to resolve the image, the effect of the Bayer pattern or other sensor filters on the digital sensor and the image processing algorithm used to interpolate sensor pixels to image pixels. Digital sensors are generally arranged in a rectangular grid pattern, making images susceptible to moire pattern artifacts, whereas film is not affected by this because of the random orientation of grains.[5]

Estimates of a photograph's resolution taken with a 35 mm film camera vary. More information may be recorded if a fine-grain film, combined with a specially-formulated developer are used. Conversely, less resolution may be recorded with poor quality optics or with coarse-grained film. A 36 mm x 24 mm frame of ISO 100-speed film is estimated to contain the equivalent of 20 million pixels.[6]

Many professional-quality film cameras use medium format or large format films. Because of the size of the imaging area, these can record higher resolution images than current top-of-the-range digital cameras. A medium format film image can record an equivalent of approximately 50 megapixels, while large format films can record around 200 megapixels (4 × 5 inch) which equates to around 800 megapixels on the largest common film format, 8 × 10 inches, without accounting for lens sharpness.[7] A medium format DSLR provides from 42 to 50 megapixels, which is similar to medium format film quality.

The medium which will be used for display, and the viewing distance, should be taken into account. For instance, if a photograph will only be viewed on a television or computer display, which can resolve approximately .3 megapixels[8] and 1-2 megapixels, respectively, or HD sets of 1080p that can display 2MP, the resolution provided by inexpensive digital cameras may be sufficient.

to prevent highlight overexposure. Nikon calls this feature D-Lighting.

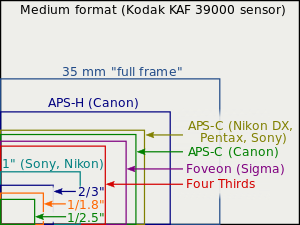

Effects of sensor size

Almost all compact digital cameras, and most digital SLRs, have sensors smaller than a 36 mm x 24 mm frame of 35 mm film. This affects aspects of the captured image and the way the camera is used. These effects include:[9]

- Increased depth of field;

- Decreased light sensitivity and increased pixel noise;

- For digital SLRs, cropping of the field of view when using lenses designed for 35 mm camera;

- Lenses may be smaller because they only need to project their image onto a smaller area;

- Increased degree of enlargement of the final image.

Depth of field at a given f-numberincreases as the area of film or image sensor decreases. This may have advantages for compact digital cameras intended for taking snapshots; more of the image will be in focus than with a larger sensor and the autofocus system does not need to be as accurate to produce an acceptable image. Photographers often limit depth of field to create certain effects, such as isolating a subject from its background. Cameras with imaging areas smaller than 36 mm x 24 mm require a wider aperture on the lens to achieve the same degree of selective focusing.[10] Depth of field can be minimized by use of large format cameras, which are rarely digital.

Light sensitivity and pixel noise are both related to pixel size, which is in turn related to sensor size and resolution. As the resolution of sensors increase, the size of the individual pixels has to decrease. This smaller pixel size means that each pixel collects less light and the resulting signal must be amplified more to produce the final value. Noise is also amplified and the signal-to-noise ratio decreases, and the higher noise floor means that less useful information is extracted from the darker parts of the image.[9]

Some digital SLRs use lens mounts originally designed for film cameras. If the camera has a smaller imaging area than the lens' intended film frame, its field of view is cropped. This crop factor is often called a "focal length multiplier" because the effect can be calculated by multiplying the focal length of the lens. For lenses that are not designed for a smaller imaging area whilst using the 35 mm-compatible lens mount, this has the beneficial side effect of only using the centre part of the lens, where the image quality is in some aspects higher.[citation needed] Only expensive digital SLRs and very rarely expensive 'compacts' have 36mm × 24 mm sensors, eliminating depth of field and crop factor problems when compared to 35 mm film cameras.[citation needed]

The smaller sensor size of digital compact cameras means that prints are extreme enlargements of the original image, and that the lens must perform well in order to provide enough resolution to match the tiny pixels on the sensor. Most digital compacts have sensors that exceed the maximum resolution that the lens is capable of delivering. Increased sensor resolution may have affect the image resolution because of increased noise reduction.[citation needed]

Cleanliness

Dust on the image plane is a constant issue for photographers. DSLR cameras are especially prone to dust problems because the sensor remains in place, where a film advances through the camera for each exposure. Debris in the camera, such as dust or sand, may scratch the film; a single grain of sand can damage a whole roll of film. As film cameras age, they can develop burs in their rollers. With a digital SLR, dust is difficult to avoid but is easy to rectify using a computer with image-editing software. Some digital SLRs have systems that remove dust from the sensor by vibrating or knocking it, sometimes in conjunction with software that remembers where dust is located and removes dust-affected pixels from images.[citation needed]

Compact digital cameras are fitted with fixed lenses; dust is excluded from the imaging area. Similar film cameras are often only light-tight and not environmentally sealed. Some modern DSLRs, like the Olympus E-3, incorporate extensive dust and weather seals to avoid this problem.

Integrity

Film produces a first generation image, which contains only the information admitted through the aperture of the camera. Trick photography is more difficult with film; in law enforcement and where the authenticity of an image is important, like passport or visa photographs, film provides greater security over most digital cameras, as digital files may have be modified using a computer. However, some digital cameras can produce authenticated images. If someone modifies an authenticated image, it can be determined with special software.[11] SanDisk claims to have developed a write-once memory stick for cameras, and that the images once written cannot be altered. [12]

From an artistically conservative standpoint, some practitioners believe that the use of film offers a more authentic mode of expression than with easily enhanced digital images. As with the earlier transition from oil painting to photography, or from photographic plates to film photography, older methods are more expensive, thus encourage more selectivity and additional consideration.[13]

Converting film to digital

Film photographs may be digitally scanned into a computer with a scanner. They may then be manipulated as digital images. Several methods are available:

- A reflective image scanner may be used; inexpensive flatbed scanners can scan an image on paper media.

- An expensive and very high resolution drum scanner can scan reflective and transparent media.

- A Flying spot scanner can scan reels of film quickly.

- A dedicated film scanner, such as the Nikon Coolscan (pictured), can scan 35 mm transparencies and negatives. Other film scanners can scan 120 film, typically up to 6 x 7 cm or 6 x 9 cm.

- A digital camera on a copy stand can photograph the source image.

- A slide projector can project the image from a transparency onto a screen, so the digital camera can photograph it.

Archiving

Films and prints, processed and stored in ideal conditions, may remain substantially unchanged for more than 100 years. Gold or platinum toned prints may have a lifespan limited by that of the base material.[citation needed]

The archival potential of digital images is poorly understood because digital media have existed for 50 years. The physical stability of the recording medium, future readability of the storage medium and future readability of the file formats used for storage are issues to be considered. Some types of digital media are incapable of storing data for prolonged periods. Magnetic disks and tapes may lose their data after twenty years, flash memory cards in fewer years. Good quality optical media may be the most durable digital storage media.[citation needed]

It is important to consider the future readability of storage media. Assuming the storage media can continue to hold data for prolonged periods of time. The equipment necessary to read media may become unavailable. For example, 5¼-inch floppy disks were first made available in 1976 but the drives to read them are already extremely rare.

The ability to decode the data is important. Digital cameras save photographs in JPEG format, that has existed for approximately 15 years. Because the instructions on how to decode this format are publicly known, it is unlikely that this files will be unreadable in the future.

Most professional cameras can save in a Raw image format, the future of which is less certain. Some of these formats contain proprietary data which is encrypted or protected by patents, and could be abandoned by their makers for economic or other reasons, causing possible future difficulty in decoding these files unless the camera makers were to release information on the file formats.[14]

In order to counteract the file format problems, many organizations prefer to choose an open and popular file format, increasing the chance that software will exist to decode the file in the future.[citation needed] Many organizations take an active approach to archiving rather than relying on the future readability of digital files, relying upon the ability to make perfect copies of digital media. Rather than leaving data on in format which may potentially become unreadable or unsupported, the information can be copied to newer media without loss of quality.[citation needed] Digital images may be printed and stored like traditional photographs.[citation needed]

Convenience and flexibility

Flexibility and convenience have been the main reasons for the widespread adoption of digital cameras.[citation needed] With film cameras, film is normally completely exposed before being processed. When the film is returned it is possible to see the photograph. Most digital cameras incorporate a liquid crystal display that allows the image to be viewed immediately after capture. The photographer may delete undesired or unnecessary photographs. The screen allows the photographer to repeat the image if required. When a user desires prints, it is only necessary to print the required photographs.

With digital imaging, images may be conveniently stored on a personal computer. Professional-grade digital cameras can store pictures in a raw image format, which stores the output from the sensor rather than processing it immediately to form an image. When edited in suitable software, such as Adobe Photoshop or the GNU program GIMP (which uses dcraw to read raw files), the user may manipulate certain parameters of the image, such as contrast, sharpness or color balance before producing an image. Alternatively, users may retouch the content of recorded JPEG images; software for this purpose may be provided with consumer-grade cameras.

Digital photography allows the collection of a large quantity of archival documents in a short period of time, which has benefits for researchers such as convenience, lower cost and increased flexibility in using the documents.[15]

For large format and ultra large format photography, film may have some advantages over digital cameras, such as price and flexibility, when used outside the studio environment. Large digital rotating line cameras provide similarly high performance, but scan mechanically rather than use a single sensor, making them expensive and not very portable. [citation needed]

Price

Film and digital imaging systems have different cost emphases. Digital cameras are significantly more expensive than film equivalents, but taking photographs with them is effectively cost-free. The price of digital cameras continues to fall. Other costs associated with digital photography are specialist batteries, memory cards, paper, printer ink cartridges and long-term storage.

High quality film cameras are less complicated and therefore less expensive, ongoing film and processing costs being the major expense. The photographer will identify unsuitable images when developing and possibly printing them have been paid for.

With many photographers switching to digital, film cameras and lenses are now available on the second-hand market at often much-reduced prices, allowing for semi-professional and even professional film cameras to be owned by people who would once never have been able to afford them.

References

- ^ Mark Galer and Les Horvat (2005). Digital Imaging. Elsevier. ISBN 024051971X.

- ^ Glenn Rand, David Litschel, Robert Davis (2005). Digital Photographic Capture. Elsevier. ISBN 0240806328.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marvin J. Rosen and David L. Devries (2002). Photography & Digital Imaging. Kendall Hunt. ISBN 0757511597.

- ^ Jurij F. Tasič, Mohamed Najim and Michael Ansorge (2003). Intelligent Integrated Media Communication Techniques. Springer. ISBN 1402075529.

- ^ Issac Amadror (2009). "3". The Theory of the Moiré Phenomenon. Springer London. ISBN 978-1-84882-180-4.

- ^ Langford, Michael (2000). Basic Photography (7th Ed.). Oxford: Focal Press. ISBN 0 240 51592 7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Resolution Test Area 2: trees and Mountains R. N. Clark, 8 April 2001. Retrieved 2 September 2006.

- ^ Why do Images Look Crappy Played on a TV

- ^ a b Bob Atkins. "Size Matters". Photo.Net Equipment Article, 2003.

- ^ Bob Atkins. "Digital Depth of Field". BobAtikins.com. []

- ^ Nikon image authentication

- ^ http://www.engadget.com/2008/07/15/sandisk-introduces-write-once-worm-sd-cards/

- ^ Carbone, Kia M. 2009. "Making Contact: The Photographer's Interface with the World." Student Pulse. http://studentpulse.com/articles/57/making-contact-the-photographers-interface-with-the-world

- ^ Dean M. Chriss. "RAW Facts: The short life of today's RAW files: Demystifying the Debacle". DMCPhoto online article, April 29, 2005.

- ^ http://www.physorg.com/news139751840.html,Accelerated research using a digital camera