Timbuktu

Timbuktu

Tumbutu | |

|---|---|

City | |

| transcription(s) | |

| • Koyra Chiini: | Tumbutu |

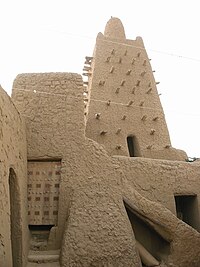

Sankore Mosque in Timbuktu | |

| Country | |

| Region | Tombouctou Region |

| Cercle | Timbuktu Cercle |

| Settled | 10th century |

| Elevation | 261 m (856 ft) |

| Population (1998[1]) | |

| • Total | 31,973 |

Timbuktu (Timbuctoo) (Koyra Chiini: Tumbutu; French: Tombouctou) is a city in Tombouctou Region, in the West African nation of Mali. It was made prosperous by the tenth mansa of the Mali Empire, Mansa Musa. It is home to Sankore University and other madrasas, and was an intellectual and spiritual capital and centre for the propagation of Islam throughout Africa in the 15th and 16th centuries. Its three great mosques, Djingareyber, Sankore and Sidi Yahya, recall Timbuktu's golden age. Although continuously restored, these monuments are today under threat from desertification.[2]

Populated by Songhay, Tuareg, Fulani, and Mandé people, Timbuktu is about 15 km north of the Niger River. It is also at the intersection of an east–west and a north–south Trans-Saharan trade route across the Sahara to Araouane. It was important historically (and still is today) as an entrepot for rock-salt originally from Taghaza, now from Taoudenni.

Its geographical setting made it a natural meeting point for nearby west African populations and nomadic Berber and Arab peoples from the north. Its long history as a trading outpost that linked west Africa with Berber, Arab, and Jewish traders throughout north Africa, and thereby indirectly with traders from Europe, has given it a fabled status, and in the West it was for long a metaphor for exotic, distant lands: "from here to Timbuktu."

Timbuktu's long-lasting contribution to Islamic and world civilization is scholarship. Timbuktu is assumed to have had one of the first universities in the world. Local scholars and collectors still boast an impressive collection of ancient Greek texts from that era.[3] By the 14th century, important books were written and copied in Timbuktu, establishing the city as the centre of a significant written tradition in Africa.[4]

History

Origins

Timbuktu was established by the nomadic Tuareg as early as the 10th century. Although Tuaregs founded Timbuktu, it was only as a seasonal settlement. Roaming the desert during the wet months, in summer they stayed near the flood plains of the Inner Niger Delta. Since the terrain directly at the water wasn’t suitable due to mosquitoes, a well was dug a few miles from the river.[5][6]

Permanent Settlements

In the eleventh century merchants from Djenne set up the various markets and built permanent dwellings in the town, establishing the site as a meeting place for people traveling by camel. They also introduced the Islam and reading, through the Qur'an. Before Islam, the population worshiped Ouagadou-Bida, a mythical water-serpent of the Niger River.[7] With the rise of the Ghana Empire, several Trans Saharan trade routes had been established. Salt from Mediterranean Africa was traded with West-African gold and ivory, and large numbers of slaves. Halfway through the eleventh century, however, new goldmines near Bure made for an eastward shift of the trade routes. This development made Timbuktu a prosperous city where goods from camels were loaded on boats on the Niger.

Rise of the Mali Empire

During the twelfth century, the remnants of the Ghana Empire were invaded by the Sosso Empire king Soumaoro Kanté.[9] Muslim scholars from Walata (beginning to replace Aoudaghost as trade route terminus) fled to Timbuktu and solidified the position of the Islam. Timbuktu had become a center of Islamic learning, with its Sankore University and 180 Quranic schools.[5] In 1324 Timbuktu was peacefully annexed by king Musa I, returning from his pilgrimage to Mecca. The city now part of the Mali Empire, king Musa I ordered the construction of a royal palace and, together with his following of hundreds of Muslim scholars, built the learning center of Djingarey Ber in 1327.

By 1375, Timbuktu appeared in the Catalan Atlas, showing that it was, by then, a commercial center linked to the North-African cities and had caught Europe's eye.[10]

Tuareg Rule & the Songhayan Empire

With the power of the Mali Empire waning in the first half of the 14th century, Maghsharan Tuareg took control of the city in 1433-1434 and installed a Sanhaja governor.[11] Thirty years later however, the rising Songhay Empire expanded, absorbing Timbuktu in 1468-1469. Lead by consecutively Sunni Ali Ber (1468–1492), Sunni Baru (1492–1493) and Askia Mohammad I (1493–1528), who brought the Songhay Empire and Timbuktu a golden age. With the capital of the empire being Gao, Timbuktu enjoyed a relatively autonomous position. Merchants from Ghadames, Awjidah, and numerous other cities of North Africa gathered there to buy gold and slaves in exchange for the Saharan salt of Taghaza and for North African cloth and horses.[12] Leadership of the Empire stayed in the Askia dynasty until 1591, although internal fights led to a decline of prosperity in the city.

Moroccan Occupation

The city's capture on August 17, 1591 by an army sent by the Saadi ruler of Morocco, Ahmad I al-Mansur, and led by pasha Mahmud B. Zarqun in search of gold mines, brought the end of an era of relative autonomy. Intellectually, and to a large extent economically, Timbuktu now entered a long period of decline. In 1593, Saadi cited 'disloyalty' as the reason for arresting, and subsequently killing or exiling many of Timbuktu's scholars, including Ahmad Baba.[13] Perhaps the city's greatest scholar, he was forced to move to Marrakesh because of the intellectual oppostion to the city's Morrocan governor, where he continued to generate attention of the scholarly world.[14] Ahmad Baba later returned to Timbuktu, where he died in 1608. The ultimate decline continued, with the increasing trans-atlantic traderoutes (transporting African slaves, including leaders and scholars of Timbuktu) marginalising Timbuktu's role. While initially controlling the Morocco - Timbuktu traderoutes, the grip of the Moroccans on the city began losing its strength in the period until 1780, and in the early 19th century the Empire didn't succeed in protecting the city against invasions and the subsequent short occupations of the Tuareg (1800), Fula (1813) and Tukular 1840.[6][13] It is uncertain whether the Tukular were still in control,[15] or if the Tuaregs had once again regained power[16], when the French arrived.

Discovery by the West

Historic descriptions of the city had been around since Leo Africanus' account in the first half of the 16th century, and they prompted several European individuals and organizations to make great efforts to discover Timbuktu and its fabled riches. In 1788 a group of titled Englishmen formed the African Association with the goal of finding the city and charting the course of the Niger River. The earliest of their sponsored explorers was a young Scottish adventurer named Mungo Park, who made two trips in search of the Niger River and Timbuktu (departing first in 1795 and then in 1805). It is believed that Park was the first Westerner to have reached the city, but he died in modern day Nigeria without having the chance to report his findings.[17] In 1824, the Paris-based Société de Géographie offered a 10,000 franc prize to the first non-Muslim to reach the town and return with information about it.[18] The Briton Gordon Laing arrived in September 1826 but was killed shortly after by local Muslims who were fearful of European discovery and intervention.[19] The Frenchman René Caillié arrived in 1828 traveling alone disguised as a Muslim; he was able to safely return and claim the prize.[20]

Robert Adams, an African-American sailor, claimed to have visited the city in 1811 as a slave after his ship wrecked off the African coast.[21] He later gave an account to the British consul in Tangier, Morocco in 1813. He published his account in an 1816 book, The Narrative of Robert Adams, a Barbary Captive (still in print as of 2006), but doubts remain about his account.[22] Three other Europeans reached the city before 1890: Heinrich Barth in 1853 and the German Oskar Lenz with the Spaniard Cristobal Benítez in 1880.

Part of the French Colonial Empire

After the scramble for Africa had been formalized in the Berlin Conference, land between the 14th meridian and Miltou, Chad would become French territory, bound in the south by a line running from Say, Niger to Baroua. Although the Timbuktu region was now French in name, the principle of effectivity needed France to actually hold power in those areas assigned, e.g. by signing agreements with local chiefs, setting up a government and making use of the area economically, before the claim would be definitive. On December 28, 1893, the city, by then in a state of poverty, was annexed by a small group of French, lead by lieutenant Boiteux: Timbuktu was now part of French Sudan, a colony of France.[23] This situation lasted until 1902: after dividing part of the colony back in 1899, the remaining areas were now reorganized and, for a brief period, called Senegambia and Niger. Only two years later, in 1904, another reorganization followed and Timbuktu became part of Upper Senegal and Niger until, in 1920, the colony assumed its old name of French Sudan once again.[15]

World War II

During World War II, several legions were recruited in French Soudan, with some coming from Timbuktu, to help general Charles de Gaulle fight Nazi-occupied France and southern Vichy France.[17]

About 60 British merchant seamen from the SS Allende (Cardiff), sunk on the 17th March 1942 off the South coast of West Africa, were held prisoner in the city during the Second World War. Two months later, after having been transported from Freetown to Timbuktu, two of them, AB John Turnbull Graham (2 May 1942, age 23) and Chief Engineer William Soutter (28 May 1942, age 60) died there in May 1942. Both men were buried in the European cemetery - possibly the most remote British war graves tended by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.[24]

Independency & Onwards

After World War II had come to an end, the French government under Charles de Gaulle granted the colony more and more freedom. After a period as part of the short-lived Mali Federation, the Republic of Mali was proclaimed on September 22, 1960. After a November 19, 1968, a new constitution was created in 1974, making Mali a single-party state.[25] By then, the canal linking the city with the Niger River had already been filled with sand from the encroaching desert. Severe droughts hit the Sahel region in 1973 and 1985, decimating the Tuareg population around Timbuktu who relied on goat herding. The Niger's water level dropped, postponing the arrival of food transport and trading vessels. The crisis drove many of the inhabitants of Tombouctou Region to Algeria and Libya. Those who stayed relied on humanitarian organisations such as UNICEF for food and water.[26]

Etymology

Over the centuries, the spelling of Timbuktu has varied a great deal: from traveler Antonius Malfante’s “Thambet”, used in a letter he wrote in 1447 and also adopted by Ca Da Mosto in his “Voyages of Cadamosto, to Heinrich Barth’s Timbúktu and Timbu’ktu. As well as its spelling, Timbuktu’s etymology is still open to discussion.[27]

At least four possible origins of the name of Timbuktu have been described:

- Songhai origin: both Leo Africanus and Heinrich Barth believed the name was derived from two Songhau words. Leo Africanus argued: “This name [Timbuktu] was in our times (as some think) imposed upon this kingdom from the name of a certain town so called, which (they say) king Mense Suleiman founded in the yeere of the Hegeira 610 [1213-1214][28]."[29] The word itself consisted of two parts, tin (wall) and butu ("Wall of Butu"), the meaning of which Africanus did not explain. Heinrich Barth suggested: "the original form of the name was the Songhai form Túmbutu, from whence the Imóshagh made Tumbýtku, which was afterwards changed by the Arabs into Tombuktu” (1965[1857]: 284). On the meaning of the word Barth noted the following: “the town was probably so called, in the Songhai language: if it were a Temáshight word, it would be written Tinbuktu. The name is generally interpreted by Europeans [as] "well of Buktu", but "tin" has nothing to do with well”. (Barth 1965:284-285 footnote)

- Berber origin: Cissoko mentions a different etymology: the Tuareg founders of the city gave it a Berber name, a word composed of two parts: tim, the feminine form of In, meaning “place of”and “bouctou”, a contraction of the Arab word nekba (small dune). Hence, Timbuktu would mean “place covered by small dunes”.[30]

- Abd al-Sadi offers a third explanation in his Tarikh al-Sudan (ca. 1655): “in the beginning it was there that travelers arriving by land and water met. They made it the depot for their utensils and grain. Soon this place became a cross-roads of travelers who passed back and forth through it. They entrusted their property to a slave called Timbuctoo, [a] word that, in the language of those countries means the old”.

- The French orientalist René Basset forwarded another theory: the name derives from the Zenaga root b-k-t, meaning “to be distant” or “hidden”, and the feminine possessive particle tin. The meaning “hidden” could point to the city's location in a slight hollow.[10]

The validity of these theories depends on the identity of the original founders of the city: remnants dated from before the Songhay Empire exist and stories about earlier history point towards the Tuareg.[5][6] But, as recent as 2000, archeological research has not found remains dating from the 11th/12th century due to meters of sand that have buried the remains over the past centuries.[31]. With no consensus the etymology of Timbuktu remains unclear.

Legendary tales

Tales of Timbuktu's fabulous wealth helped prompt European exploration of the west coast of Africa. Among the earliest descriptions of Timbuktu are those of Leo Africanus, Ibn Battuta, and Shabeni.

Leo Africanus

Perhaps most famous among the accounts written about Timbuktu is that by Leo Africanus. Born al-Hasan ibn Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Wazzan, Leo Africanus was an ambassador serving the Sultan of Fez when, in 1518 he was captured by Christian pirates and delivered to the Pope in Rome. There he converted from Islam to Christianity and wrote a book on Africa.[32] Describing Timbuktu when the Songhai empire was at its height, the English edition of his book includes the description:

The rich king of Tombuto hath many plates and scepters of gold, some whereof weigh 1300 pounds. ... He hath always 3000 horsemen ... (and) a great store of doctors, judges, priests, and other learned men, that are bountifully maintained at the king's cost and charges.[33]

According to Leo Africanus, there were abundant supplies of locally produced corn, cattle, milk and butter, though there were neither gardens nor orchards surrounding the city.

Shabeni

Shabeni was a merchant from Tetouan, Morocco who was captured and ended up in England where he told his story of how as a child of 14, around 1787, he had gone with his father to Timbuktu. A version of his story is related by James Grey Jackson in his book An Account of Timbuctoo and Hausa, 1820:

On the east side of the city of Timbuctoo, there is a large forest, in which are a great many elephants. The timber here is very large. The trees on the outside of the forest are remarkable...they are of such a size that the largest cannot be girded by two men. They bear a kind of berry about the size of a walnut, in clusters consisting of from ten to twenty berries. Shabeeny cannot say what is the extent of this forest, but it is very large.

Centre of learning

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv, v |

| Reference | 119 |

| Inscription | 1988 (12th Session) |

| Endangered | 1990-2005 |

During the early 15th century, a number of Islamic institutions were erected. The most famous of these is the Sankore mosque, also known as the University of Sankore.

While Islam was practiced in the cities, the local rural majority were non-Muslim traditionalists. Often the leaders were nominal Muslims in the interest of economic advancement while the masses were traditionalists.

University of Sankore

Sankore, as it stands now, was built in 1581 AD (= 989 A. H.) on a much older site (probably from the 13th or 14th century) and became the center of the Islamic scholarly community in Timbuktu. The "University of Sankore" was a madrassah, very different in organization from the universities of medieval Europe. It was composed of several entirely independent schools or colleges, each run by a single master or imam. Students associated themselves with a single teacher, and courses took place in the open courtyards of mosque complexes or private residences. The primary focus of these schools was the teaching of the Qur'an, although broader instruction in fields such as logic, astronomy, and history also took place. Scholars wrote their own books as part of a socioeconomic model based on scholarship. The profit made by buying and selling of books was only second to the gold-salt trade. Among the most formidable scholars, professors and lecturers was Ahmed Baba – a highly distinguished historian frequently quoted in the Tarikh al-Sudan and other works.

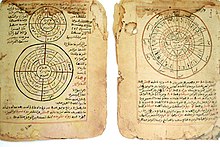

The manuscripts and libraries of Timbuktu

The most outstanding treasure at Timbuktu are the 100,000 manuscripts kept by the great families from the town.[34]. These manuscripts, some of them dated from pre-Islamic times and 12th century, have been preserved as family secrets in the town and in other villages nearby. The majority were written in Arabic or Fulani, by wise men coming from the Mali Empire. Their contents are didactic, especially in the subjects of astronomy, music, and botany. More recent manuscripts deal with law, sciences and history (with the important 17th century chronicles, Tarikh al-fattash and Tarikh al-Sudan), religion, trade, etc.

The Ahmed Baba Institute (Cedrab), founded in 1970 by the government of Mali, with collaboration of Unesco, holds some of these manuscripts in order to restore and digitize them. More than 18,000 manuscripts have been collected by the Ahmed Baba centre, but there are an estimated 300,000-700,000 manuscripts in the region.[35]

The collection of ancient manuscripts at the University of Sankore and other sites around Timbuktu document the magnificence of the institution, as well as the city itself, while enabling scholars to reconstruct the past in fairly intimate detail. Dating from the 16th to the 18th centuries, these manuscripts cover every aspect of human endeavor and are indicative of the high level of civilization attained by West Africans at the time. In testament to the glory of Timbuktu, for example, a West African Islamic proverb states that "Salt comes from the north, gold from the south, but the word of God and the treasures of wisdom come from Timbuktu."

From 60 to 80 private libraries in the town have been preserving these manuscripts: Mamma Haidara Library; Fondo Kati Library (with approximately 3,000 records from Andalusian origin, the oldest dated from 14th and 15th centuries); Al-Wangari Library; and Mohamed Tahar Library, among them. These libraries are considered part of the "African Ink Road" that stretched from West Africa connecting North Africa and East Africa. At one time there were 120 libraries with manuscripts in Timbuktu and surrounding areas. There are more than one million objects preserved in Mali with an additional 20 million in other parts of Africa, the largest concentration of which is in Sokoto, Nigeria, although the full extent of the manuscripts is unknown. During the colonial era efforts were made to conceal the documents after a number of entire libraries were taken to Paris, London and other parts of Europe. Some manuscripts were buried underground, while others were hidden in the desert or in caves. Many are still hidden today. The United States Library of Congress microfilmed a sampling of the manuscripts during an exhibition there in June 2003. In February 2006 a joint South African/Malian effort began investigating the Timbuktu manuscripts to assess the level of scientific knowledge in Timbuktu and in the other regions of West Africa.[36]

Timbuktu today

Today, Timbuktu is an impoverished town, although its reputation makes it a tourist attraction to the point where it even has an international airport (Timbuktu Airport). It is one of the eight regions of Mali, and is home to the region's local governor. It is the sister city to Djenné, also in Mali. The 1998 census listed its population at 31,973, up from 31,962 in the census of 1987.[37]

Timbuktu is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, listed since 1988. In 1990, it was added to the list of World Heritage Sites in danger due to the threat of desert sands. A program was set up to preserve the site and, in 2005, it was taken off the list of endangered sites. However, new constructions are threatening the ancient mosques, a UNESCO Committee warns.[38]

Timbuktu was one of the major stops during Henry Louis Gates' PBS special "Wonders of the African World". Gates visited with Abdel Kadir Haidara, curator of the Mamma Haidara Library together with Ali Ould Sidi from the Cultural Mission of Mali. It is thanks to Gates that an Andrew Mellon Foundation grant was obtained to finance the construction of the library's facilities, later inspiring the work of the Timbuktu Manuscripts Project. Unfortunately, no practising book artists exist in Timbuktu although cultural memory of book artisans is still alive, catering to the tourist trade. The town is home to an institute dedicated to preserving historic documents from the region, in addition to two small museums (one of them the house in which the great German explorer Heinrich Barth spent six months in 1853-54), and the symbolic Flame of Peace monument commemorating the reconciliation between the Tuareg and the government of Mali.

Attractions

Timbuktu's vernacular architecture is marked by mud mosques, which are said to have inspired Antoni Gaudí. These include

- Djinguereber Mosque, built in 1327 by El Saheli[40]

- Sankore Mosque, also known as Sankore University, built in the early fifteenth century

- Sidi Yahya mosque, built in the 1441 by Mohamed Naddah.

Other attractions include a museum, terraced gardens and a water tower.

Language

The main language of Timbuktu is a Songhay language called Koyra Chiini, spoken by over 80% of residents. Smaller groups, numbering 10% each before many were expelled during the Tuareg/Arab rebellion of 1990-1994, speak Hassaniya Arabic and Tamashek.

Climate

The weather is hot and dry throughout much of the year with plenty of sunshine. Average daily maximum temperatures in the hottest months of the year - May and June - exceed 40°C. Temperatures are slightly cooler, though still very hot, from July through September, when practically all of the meager annual rainfall occurs. Only the winter months of December and January have average daily maximum temperatures below 32°C.

| Climate data for Timbuktu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization [41] | |||||||||||||

Famous people connected with Timbuktu

- Cristina Nardone (1983-2008) Served as a Peace Corps Volunteer and Project Manager for AED who sacrificed her life to help others.

- Ali Farka Toure (1939–2006) Born in Kanau, in the Timbuktu region.[42]

- Heinrich Barth (1821–1865) German traveller and scholar and one of the first Europeans to investigate African history[43]

- Bernard Peter de Neumann, GM (1917–1972) "The Man From Timbuctoo".[44] Held prisoner of war there along with other members of the crew of the Criton during 1941-1942.

- Ibn Battuta (1304–1368) made a famous journey to Timbuktu, along with many others throughout his lifetime.[45]

- Mungo Park (1771-1806) was the first European to reach the Niger River. On his second journey down the river he passed by Timbuktu but was not able to make it to the city due to local aggression. He drowned in the Bussa rapids a few hundred miles further down river.[17]

- Mardochée abi Serour (merchant), born circa 1930 in Aqqa (a Saharian oasis) traded merchandise between Mogador (presently Essaouira) and Timbuktu, and even owned a house in Timbuktu.[46]

- René Caillié (1799-1838) was the first European to return alive from Timbuktu

In popular culture

The image of the city as mysterious or mythical has survived to the present day in other countries: a survey among 150 young Britons in 2006 found 34% did not believe the town existed, while the other 66% considered it "a mythical place".[47]

Donald Duck uses Timbuktu as a safe haven, and a Donald Duck comic subseries is situated in the city.[48] In the 1970 Disney animated feature The Aristocats, Edgar the butler places the cats in a trunk which he plans to send to Timbuktu. It is mistakenly noted to be in French Equatorial Africa, instead of French West Africa.[49]

Timbuktu also makes an appearance in the British musical Oliver when The Artful Dodger sings to Nancy, "I'd do anything for you, dear, anything, for you" to which Nancy sings in reply, "Paint your face bright blue?" "Anything", Dodger responds. "Go to Timbuktu?" Nancy asks. "And back again", Dodger responds, and the song continues.

Sister cities

- Chemnitz, Germany[50]

- Chemnitz, Germany[50] - Blaenllechau, Wales, United Kingdom

- Blaenllechau, Wales, United Kingdom - Hay-on-Wye, Wales, United Kingdom

- Hay-on-Wye, Wales, United Kingdom - Kairouan, Tunisia

- Kairouan, Tunisia - Marrakech, Morocco

- Marrakech, Morocco - Saintes, France

- Saintes, France - Tempe, Arizona, United States[47]

- Tempe, Arizona, United States[47] - Istanbul, Turkey

- Istanbul, Turkey

See also

Notes

- ^ [1]

- ^ Timbuktu — World Heritage (Unesco.org)

- ^ Timbuktu. (2007). Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Okolo Rashid. Legacy of Timbuktu: Wonders of the Written Word Exhibit - International Museum of Muslim Cultures [2]

- ^ a b c History of Timbuktu, Mali - Timbuktu Educational Foundation

- ^ a b c Early History of Timbuktu - The History Channel Classroom

- ^ Homer, Curry. Snatched from the Serpent. Berrien Springs, Michigan: Frontiers Adventist.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Demhardt, Imre Josef (August 2006). "Hopes, Hazards and a Haggle: Perthes' Ten Sheet "Karte von Inner-Afrika"" (PDF). International Symposium on "Old Worlds-New Worlds": The History of Colonial Cartography 1750-1950 (August 21–23). Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands: Working Group on the History of Colonial Cartography in the 19th and 20th centuries International Cartographic Association (ICA-ACI). p. 16.

{{cite conference}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Mann, Kenny (1996). hana Mali Songhay: The Western Sudan. (African Kingdoms of the Past Series). South Orange, New Jersey: Dillon Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Hunwick, John O. (2003). Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-sudan down to 1613. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. p. 414. ISBN 9004128220.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Bosworth, Edmund C. (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 521–522. ISBN 9004153888.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Timbuktu". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 9 Januari 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Boddy-Evans, Alistair. "Timbuktu: The El Dorado of Africa". About.com Guide. Retrieved 7 Februari 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Timbuktu Hopes Ancient Texts Spark a Revival". New York Times. August 7, 2007.

The government created an institute named after Ahmed Baba, Timbuktu's greatest scholar, to collect, preserve and interpret the manuscripts.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

Entry on Timbuktu at [[Archnet|Archnet.com]], retrieved 12 February 2010

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "TIMBUKTU (French spelling Tombouctou)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. V26. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1911. p. 983. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ a b c Larry Brook, Ray Webb (1999) Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Timbuktu. Retrieved d.d. September 22, 2009.

- ^ de Vries, Fred (7 Januari 2006). "Randje woestijn". de Volkskrant (in Dutch). Amsterdam: PCM Uitgevers. Retrieved 7 Februari 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Fleming F. Off the Map. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2004. pp. 245–249. ISBN 0-87113-899-9.

- ^ Caillié, René (1830), Travels through Central Africa to Timbuctoo; and across the Great Desert, to Morocco, performed in the years 1824-1828 (2 Vols), London: Colburn & Bentley Google books: Volume 1, Volume 2

- ^ Calhoun, Warren Glenn; From Here to Timbuktu, p. 273 ISBN 0-7388-4222-2

- ^ Sandford, Charles Adams (2005). The Narrative of Robert Adams, a Barbary Captive: Critical Edition. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. XVIII (preface). ISBN 978-0-521-84284-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Maugham, Reginal Charles Fulke (Januari 1924). "NATIVE LAND TENURE IN THE TIMBUKTU DISTRICTS". Journal of the Royal African Society. 23 (90). London: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Royal African Society: 125–130. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Neumann, Bernard de (1 November 2008), British Merchant Navy Graves in Timbuktu, retrieved 17 February 2010

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Arts & Life in Africa, 15 October 1998, retrieved 20 February 2010

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^

Brooke, James (23 March 1988). "Timbuktu Journal; Sadly, Desert Nomads Cultivate Their Garden". New York Times. New York City, NY: Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Pelizzo, Riccardo (2001). "Timbuktu: A Lesson in Underdevelopment" (PDF). Journal of World-Systems Research. 7 (2): 265–283. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Collins, Robert O. (1990) Western African History, London: Markus Wiener Publishers.

- ^ Leo Africanus (1896), The History and Description of Africa (PDF), London: Hakluyt Society. p.3

- ^ Cissoko, S.M (1996). Toumbouctou et l’ Empire Songhai. Paris: L’ Harmattan

- ^ Bovill, E. W. (1921). The Encroachment of the Sahara on the Sudan, Journal of the African Society 20: p. 174-185

- ^ For biographical information on Leo Africanus, see Natalie Zemon Davis, "Trickster Travels: A Sixteenth-Century Muslim Between Worlds" (Hill and Wang: New York) 2006.

- ^ Leo Africanus 1896, pp. 824-825 Vol. 3 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLeo_Africanus1896 (help)

- ^ Un patrimoine inestimable en danger : les manuscrits trouvés à Tombouctou, par Jean-Michel Djian dans Le Monde diplomatique d'août 2004.

- ^ Reclaiming the Ancient Manuscripts of Timbuktu

- ^ Curtis Abraham, "Stars of the Sahara", New Scientist, 18 August 2007: 37-39

- ^ 2007

- ^ UNESCO July 10, 2008.

- ^ Caption by Scott, Michon. "Tombouctou, Mali : Image of the Day". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ^ Salak, Kira. "Photos from "KAYAKING TO TIMBUKTU"". National

Geographic Adventure.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 10 (help) - ^ World Weather Information Service - Tombouctou, World Meteorological Organization, retrieved 2009-10-19

- ^ African star Ali Farka Toure dies, BBC News d.d. March 7, 2006. Retrieved online from BBC Online d.d. September 22, 2009.

- ^ Heinrich Barth, Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa; being a Journal of an Expedition undertaken under the auspices of H.B.M.'s Government in the years 1849-1855, Volume 1 page 534 (1857). "In the course of my travels, particularly during my stay in Timbuctu". Retrieved d.d. September 22, 2009.

- ^ The Daily Express, 10 February 1943. Front Page: The Man From Timbuctoo

- ^ Ross E. Dunn (2005) The adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim traveler of the fourteenth century, page 305. Retrieved d.d. September 22, 2009.

- ^ Charles de Foucauld, Reconnaissance du Maroc

- ^ a b "Search on for Timbuktu's twin" BBC News, 18 October 2006. Retrieved 28 March 2007

- ^ Donald Duck Timboektoe subseries (Dutch) on the C.O.A. Search Engine (I.N.D.U.C.K.S.). Retrieved d.d. October 24, 2009.

- ^ Notes on The Aristocats at the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 24, 2009

- ^ Von China bis nach Mali - Chemnitz ist international Sz Online - 11 December 2003

References

- Barth, Heinrich (1857), Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa: Being a journal of an expedition undertaken under the auspices of H. B. M.'s government, in the years 1849-1855. (3 Vols), New York: Harper & Brothers. Google books: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3.

- Caillié, Réné (1830), Travels through Central Africa to Timbuctoo; and across the Great Desert, to Morocco, performed in the years 1824-1828 (2 Vols), London: Colburn & Bentley. Google books: Volume 1, Volume 2.

- Dubois, Felix; White, Diana (trans.) (1896), Timbuctoo the mysterious, New York: Longmans.

- Dunn, Ross E. (2005), The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-24385-4. Originally published in 1986, ISBN 0-520-05771-6.

- Hacquard, Augustin (1900), Monographie de Tombouctou, Paris: Société des études coloniales & maritimes.

- Hunwick, John O. (1999), Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 9004112073. Pages 272-291 contain a translation into English of Leo Africanus' descriptions of the Middle Niger, Hausaland and Bornu.

- Hunwick, John O.; Boye, Alida Jay; Hunwick, Joseph (2008), The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Historic city of Islamic Africa, London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-51421-4.

- Insoll, Timothy (2001–2002), "The archaeology of post-medieval Timbuktu" (PDF), Sahara, 13: 7–11

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date format (link). - Insoll, Timothy (2004), "Timbuktu the less Mysterious?" (PDF), in Mitchell, P.; Haour, A.; Hobart, J. (eds.), Researching Africa's Past. New Contributions from British Archaeologists, Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 81–88.

- Leo Africanus (1896), The History and Description of Africa (3 Vols), London: Hakluyt Society. A facsimile of the 1600 English edition. Internet Archive: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973), Ancient Ghana and Mali, London: Methuen, ISBN 0841904316. Link requires subscription to Aluka.

- Miner, Horace (1953), The primitive city of Timbuctoo, Princeton University Press. Link requires subscription to Aluka. Reissued by Anchor Books, New York in 1965.

- Saad, Elias N. (1983), Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400–1900, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-5212-4603-2.

- Trimingham, John Spencer (1962), A History of Islam in West Africa, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-1928-50385.

Further reading

- Braudel, Fernand, 1979 (in English 1984). The Perspective of the World, vol. III of Civilization and Capitalism

- Jenkins, Mark, (June 1997) To Timbuktu, ISBN 978-0-688-11585-2 William Marrow & Co. Revealing travelogue along the Niger to Timbuktu

- Pelizzo, Riccardo, Timbuktu: A Lesson in Underdevelopment, Journal of World System Research, vol. 7, n.2, 2001, pp. 265–283, jwsr.ucr.edu/archive/vol7/number2/pdf/jwsr-v7n2-pelizzo.pdf

External links

select an article title from: Wikisource:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Saharan Archaeological Research Association - Directed by Douglas Post Park, and Peter Coutros of Yale University.

- Leo Africanus, description of Timbuktu, 1526

- Shabeni's Description of Timbuktu

- "Trekking to Timbuktu", a National Endowment for the Humanities learning project for grades 6-8

- Wonders of the African World

- The University of Sankore at Timbuktu

- The Timbuktu Libraries

- List of publications on Timbuktu. Centre for Development and the Environment, University of Oslo

- Saving Mali's written treasures

- Ancient Manuscripts from the Desert Libraries of Timbuktu, Library of Congress — exhibition of manuscripts from the Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library

- Islamic Manuscripts from Mali, Library of Congress — fuller presentation of the same manuscripts from the Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library

- Ancient Economy and Medieval Economy - Contains facts about the economy of Timbuktu in the medieval world

- "How a small African desert town is changing perceptions of the East", from Toplum Postasi, 11 July 2007

- Timbuktu materials in the Aluka digital library

Tourism