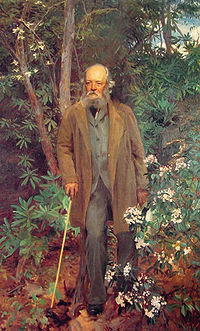

Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 26, 1822[1] |

| Died | August 28, 1903 (aged 81) |

| Occupation(s) | landscape architect, journalist |

| Spouse | Mary Olmsted |

| Children | John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. |

| Parent(s) | John and Charlotte Olmsted |

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822 – August 28, 1903) was an American journalist, landscape designer and father of American landscape architecture. Olmsted was famous for designing many well-known urban parks, including Central Park and Prospect Park in New York City.[2]

Other Frederick Law Olmsted projects include the country's oldest coordinated system of public parks and parkways in Buffalo, New York; the country's oldest state park, the Niagara Reservation in Niagara Falls, New York; one of the first planned communities in the United States, Riverside, Illinois; Mount Royal Park in Montreal in Canada; the Emerald Necklace in Boston, Massachusetts; Deering Oaks Park in Portland, Maine; the Belle Isle Park, in the Detroit River for Detroit, Michigan; the Presque Isle Park in Marquette, Michigan; the Grand Necklace of Parks in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; the Cherokee Park and entire parks and parkway system in Louisville, Kentucky; the George Washington Vanderbilt II Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina; the master plans for the University of California, Berkeley and Stanford University near Palo Alto, California; and the Montebello Park in St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada. In Chicago his projects include: Marquette Park; Jackson Park; Washington Park; the Midway Plaisance for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition; the south portion of Chicago's "'emerald necklace'" boulevard ring; and the University of Chicago campus. In Washington, D.C. he worked on the landscape surrounding the United States Capitol building.

Biography

Early life and education

Olmsted was born in Hartford, Connecticut, on April 26, 1822. His father, John Olmsted, was a prosperous merchant who took a lively interest in nature, people, and places; Frederick Law and his younger brother, John Hull, also showed this interest. His mother, Charlotte Law (Hull) Olmsted, died when he was scarcely four years old. His father remarried in 1827 to Mary Ann Bull, who shared her husband's strong love of nature and had perhaps a more cultivated taste.

When the young Olmsted was almost ready to enter Yale College, as a graduate of Phillips Academy in 1838, sumac poisoning weakened his eyes so he gave up college plans. After working as a seaman, merchant, and journalist, Olmsted settled on a farm in January 1848 on the south shore of Staten Island which his father helped him acquire. This farm, originally named the Akerly Homestead, was renamed Tosomock Farm by Olmsted. It was later renamed "The Woods of Arden" by owner Erastus Wiman. (The house in which Olmsted lived still stands at 4515 Hylan Blvd, near Woods of Arden Road.)

Marriage and family

On June 13, 1859, Olmsted married Mary Cleveland (Perkins) Olmsted, the widow of his brother John (who had died in 1857). He adopted her three sons (his nephews), among them John Charles Olmsted. Frederick and Mary had two children together who survived infancy: a daughter and a son Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.

Career

Olmsted had a significant career in journalism. In 1850, he traveled to England to visit public gardens, where he was greatly impressed by Joseph Paxton's Birkenhead Park. He subsequently wrote and published Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England in 1852. This supported his getting additional work.

Interested in the slave economy, he was commissioned by the New York Daily Times (now The New York Times) to embark on an extensive research journey through the American South and Texas from 1852 to 1857. From the Texas trip, Olmsted wrote his narrative account published as A Journey Through Texas (1857). It was recognized as the work of an astute observer of the land and lifestyles of Texas. Olmsted believed that slavery was not only morally odious, but expensive and economically inefficient. [citation needed]

His dispatches to the Times were collected into multiple volumes which remain vivid first-person social documents of the pre-war South. The last of these, Journeys and Explorations in the Cotton Kingdom (1861), was published during the first six months of the American Civil War. It helped inform and galvanize antislavery sentiment in the Northeast. These three volumes were later condensed and edited as a single volume.[3][4]

In 1865, Olmsted cofounded the magazine The Nation.

New York City's Central Park

Andrew Jackson Downing, the charismatic landscape architect from Newburgh, New York, first proposed the development of New York's Central Park in his role as publisher of The Horticulturist magazine. A friend and mentor to Olmsted, Downing introduced him to the English-born architect Calvert Vaux. Downing had brought Vaux from England as his architect collaborator. After Downing died in July 1852, in a widely publicized steamboat explosion on the Hudson River, Olmsted and Vaux entered the Central Park design competition together, against Egbert Ludovicus Viele among others.

They were announced as winners in 1858. On his return from the South, Olmsted began executing their plan almost immediately. Olmsted and Vaux continued their informal partnership to design Prospect Park in Brooklyn from 1865 to 1873.[5] That was followed by other projects. Vaux remained in the shadow of Olmsted's grand public personality and social connections.

The design of Central Park embodies Olmsted's social consciousness and commitment to egalitarian ideals. Influenced by Downing and his own observations regarding social class in England, China and the American South, Olmsted believed that the common green space must always be equally accessible to all citizens. This principle is now fundamental to the idea of a "public park", but was not assumed as necessary then. Olmsted's tenure as park commissioner in New York was a long struggle to preserve that idea.

Civil War

Olmsted took leave as director of Central Park to work as Executive Secretary of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a precursor to the Red Cross in Washington, D.C.. He tended to the wounded during the American Civil War. In 1862, during Union General George B. McClellan's Peninsula Campaign, Olmsted headed the medical effort for the sick and wounded at White House in New Kent County, where there was a ship landing on the Pamunkey River.

On the home front, Olmsted was one of the six founding members of the Union League Club of New York.

U.S. park designer

In 1863, he went west to become the manager of the Rancho Las Mariposas-Mariposa mining estate in the Sierra Nevada mountains in California. Honoring his early work in preserving Yosemite Valley, the promontory Olmsted Point near Tenaya Lake in Yosemite National Park was named after him.

In 1865 Vaux and Olmsted formed Olmsted, Vaux and Company. When Olmsted returned to New York, he and Vaux designed Prospect Park; suburban Chicago's Riverside parks; the park system for Buffalo, New York; Milwaukee, Wisconsin's grand necklace of parks; and the Niagara Reservation at Niagara Falls.

Olmsted not only created numerous city parks around the country, he also conceived of entire systems of parks and interconnecting parkways to connect certain cities to green spaces. Two of the best examples of the scale on which Olmsted worked are the park system designed for Buffalo, New York, one of the largest projects; and the system he designed for Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

- For a list of Olmsted designed parks in Buffalo, New York, please see Buffalo, New York parks system.

Olmsted was a frequent collaborator with Henry Hobson Richardson, for whom he devised the landscaping schemes for half a dozen projects, including Richardson's commission for the Buffalo State Asylum.[6]H. H. Richardson Complex

In 1883 Olmsted established what is considered to be the first full-time landscape architecture firm in Brookline, Massachusetts. He called the home and office compound Fairsted. It is now the restored Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site. From there Olmsted designed Boston's Emerald Necklace, the campuses of Stanford University and the University of Chicago, as well as the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago, among many other projects.

Death and legacy

In 1895, senility forced Olmsted to retire. In 1898 he moved to Belmont, Massachusetts and took up residence as a patient at McLean Hospital, whose grounds he had designed several years before. He remained there until his death in 1903. He was buried in the Old North Cemetery, Hartford, Connecticut.

After Olmsted's retirement and death, his sons John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. continued the work of their firm, doing business as the Olmsted Brothers. The firm lasted until 1980.

A quotation from Olmsted's friend and colleague architect Daniel Burnham could serve as an epitaph. Referring to Olmsted in March, 1893, Burnham said, "An artist, he paints with lakes and wooded slopes; with lawns and banks and forest covered hills; with mountain sides and ocean views." [7]

Academic campuses designed by Olmsted

Between 1857 and 1895, Olmsted designed numerous school and college campuses.

From 1895-1950, the Olmsted Brothers (his successors) added to some of their father's initial projects, as well as designing new ones. (See their article for projects.) Together, these works totaled 355. Some of the most famous of Frederick Law Olmsted are listed here.

Other notable Olmsted commissions

Olmsted sites by state

George Ward Park, Birmingham, Alabama

Piedmont Avenue, Berkeley, California Mountain View Cemetery, Oakland, California, dedicated in 1865 Fairmount Park, Riverside, California Public Pleasure Grounds, San Francisco, California

the Uplands" residential park, Victoria, BC, Canada, 1907 Montebello Park, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada [2] Mount Royal Park, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, inaugurated in 1876

Civic Center Park, Denver, Colorado

Seaside Park, Bridgeport, Connecticut, 18 Beardsley Park, Bridgeport, Connecticut, 1884 Bushnell Park, Hartford, Connecticut Elizabeth Park, Hartford & West Hartford, Connecticut The Institute of Living, Hartford, Connecticut, 1860s Hubbard Park, Meriden, Connecticut Walnut Hill Park, New Britain, Connecticut Brandywine Park, Wilmington, Delaware, 1886

Smithsonian National Zoological Park, Washington, D.C. United States Capitol grounds, Washington D.C Druid Hills, Georgia

Jackson Park, originally South Park, Chicago, Illinois Village of Riverside, Riverside, Illinois World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1893 Cherokee Park, Louisville, Kentucky Cushing Island, Maine Deering Oaks, Portland, ME

Druid Hill Park, Baltimore, Maryland Sudbrook Park, Baltimore, Maryland, 1889

Back Bay Fens, Arborway and Riverway, Boston, Massachusetts Arnold Arboretum, Boston, Massachusetts Franklin Park, Boston, Massachusetts Wood Island Park, Boston, Massachusetts (taken by eminent domain in the 1960s to expand Logan International Airport). The Middlesex School. Concord, Massachusetts Glen Magna Farms, Danvers, Massachusetts The Rockery, Easton, Massachusetts North Park, Fall River, Massachusetts (1901)[11] Ruggles Park, Fall River, Massachusetts South Park, (now Kennedy Park), Fall River, Massachusetts Tyler Park, Lowell, Massachusetts. Smallest park Olmsted and associates designed Buttonwood Park, New Bedford, Massachusetts

Oyster World's End, formerly the John Brewer Estate, Hingham, Massachusetts, 1889 gardens oysterville MA Swampscott, Massachusetts - Olmsted Subdivision Historic District Whitman Town Park, Whitman, Massachusetts, circa 1875

Carroll Park, Bay City, Michigan Belle Isle Park, Detroit River, Detroit, Michigan, master plan and landscape in the 1880s Elmwood Cemetery, Detroit, Michigan Presque Isle Park, Marquette, Michigan

Florham, former estate of Hamilton and Florence (Vanderbilt) Twombly. Now the campus of Fairleigh Dickinson University, Florham Park, New Jersey Branch Brook Park, Newark, New Jersey, 1900 redesign Brookdale Park, Bloomfield & Montclair, New Jersey built 1928–1931 Cadwalader Park, Trenton, New Jersey (South Mountain Reservation, Essex County, New Jersey - done by successors, not by Olmsted senior)

Washington Park, Albany, New York Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York, finished 1868[8] Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn, New York[8] Grand Army Plaza, Brooklyn, New York[8] Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, New York[8] Ocean Parkway, Brooklyn, New York[8] New York State Hospital for the Insane, Buffalo, New York Buffalo, New York parks system Manor Park, Larchmont, New York Central Park, Manhattan, New York City, 1853 (opened in 1856)[8] Riverside Park, Manhattan, New York Fort Tryon Park, New York City[8] Morningside Park, New York City[8] Riverside Drive, New York City[8] Vanderbilt Mausoleum, New York City[8] Downing Park, Newburgh, New York Niagara Reservation (now Niagara Falls State Park), Niagara Falls, New York, dedicated in 1885 Forest Park, Queens, New York Highland Park, Rochester, New York [9] Genesee Valley Park, Rochester, New York [9] Maplewood Park, Rochester, New York [9] Congress Park, Saratoga Springs, New York Kykuit Gardens, Rockefeller family estate, Westchester, New York, from 1897 Seneca Park, Rochester, New York [9] Thompson Park, Watertown NY [13]

Biltmore Estate grounds, Asheville, North Carolina Pinehurst, NC, ground broken in 1895

Wright Brothers Hill Dayton, Ohio, 1938–1940

Montebello Park, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada [2]

Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, Portland, Oregon various parks in Portland, Oregon[12]

Nay Aug Park, Scranton, Pennsylvania Town of Vandergrift, Pennsylvania, 1895

Mount Royal Park, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, inaugurated in 1876

Butler Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island

Utah State Capitol grounds masterplan, Salt Lake City, Utah

Shelburne Farms, Shelbourne, VT

various parks in Seattle, Washington[12]

Woodburn Circle, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia

Lake Park, Milwaukee, Wisconsin [10] River Park (now Riverside Park), Milwaukee, Wisconsin [10] West Park Zoological Gardens (now Washington Park), Milwaukee, Wisconsin [10]

Olmsted in popular culture

In Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City, Olmsted is featured as one of the most important figures participating in the design of the 1893 Chicago World's Columbian Exposition. In the book, his personality and actions are given significant coverage. In addition, his importance in designing the fair is highlighted (e.g., his part in picking the geographic site and his bureaucratic involvement in planning the fair).

Notes

- ^ A celebration of the life and work of Frederick Law Olmsted - Biography Page.

- ^ "F. L Olmstead is Dead; End Comes to Great Landscape Architect at Waverly, Mass. Designer of Central and Prospect Parks and Other Famous Garden Spots of American Cities." New York Times. August 29, 1903.

- ^ Cf. Wilson, p.220. "At the beginning of the Civil War, it was suggested by Olmsted's English publisher that a one-volume abridgment of all three of these books would be of interest to the British public, and Olmsted, then busy with Central Park, arranged to have this condensation made by an anti-slavery writer from North Carolina. Olmsted himself contributed to it a new introduction on The Present Crisis."

- ^ Olmsted, Frederick Law, "The Cotton Kingdom: A Traveller's Observations on Cotton and Slavery in the American Slave States. Based Upon Three Former Volumes of Journeys and Investigations", Mason Brothers, 1862

- ^ Lancaster, Clay (1972). Handbook of Prospect Park. Long Island University Press. pp. 51–66. ISBN 0-913252-06-9.

- ^ Carla Yanni, The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States, University of Minnesota Press, 2007., 127-139

- ^ Larson, The Devil in the White City

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Commissions which are within New York City are all from:White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot; AIA Guide to New York City, 4th Edition; New York Chapter, American Institute of Architects; Crown Publishers/Random House. 2000. ISBN 0-8129-31069-8; ISBN 0-8129-3107-6.

- ^ a b c d Wickes, Majorie (1988). "The Legacy of Frederick Law Olmstead" (PDF). Rochester History. L (2). Rochester Public Library. ISSN 0035-7413. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Lake Park Friends

- ^ Official website, Fall River, Massachusetts

- ^ a b "The Olmsteds in the Pacific Northwest".

- ^ City of Watertown, NY - Historic Thompson Park

See also

References

- Beveridge, Charles E (1998). Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing the American Landscape. New York, New York: Universe Publishing. ISBN 0-7893-0228-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Guide to Biltmore Estates. Asheville, North Carolina: The Biltmore Company. 2003.

- Hall, Lee (1995). Olmsted’s America: An "Unpractical" Man and His Vision of Civilization. Boston, MA: Bullfinch Press.

- Olmsted, Frederick Law (1856). A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States; With Remarks on Their Economy.

- Rybczynski, Witold (1999). A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and North America in the Nineteenth Century. New York, New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-82463-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Sears, Stephen W., To the Gates of Richmond: the Peninsula Campaign (1992) Ticknor and Fields, New York, NY ISBN 0-89919-790-6

- Wilson, Edmund, Patriotic gore; studies in the literature of the American Civil War, New York, Oxford University Press, 1962. Cf. Chapter VI on Northerners in the South: Frederick L. Olmsted.

External links

- American architects

- Landscape architects

- American landscape architects

- American urban planners

- Environmental design

- Central Park

- People of the American Civil War

- Phillips Academy

- Phillips Academy alumni

- People from Hartford, Connecticut

- People from New York City

- People from Staten Island

- 1822 births

- 1903 deaths

- Arnold Arboretum

- Emerald Necklace

- United States Sanitary Commission