Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a predominantly American term referring to a region of the Pacific Northwest of North America. The region was occupied by British and French Canadian fur traders from before 1810, and American settlers from the mid-1830s, with its coastal areas north from the Columbia River frequented by ships from all nations engaged in the fur trade, most of these from the 1790s through 1810s being Boston-based. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 ended disputed joint occupancy pursuant to the Treaty of 1818 and established the British-American boundary at the 49th parallel.

Oregon was a distinctly American term for the region. The British used the term Columbia instead.[1] The Oregon Country consisted of the land north of 42°N latitude, south of 54°40′N latitude, and west of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. The area now forms part of the present day Canadian province of British Columbia, all of the US states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming. The British presence in the region was generally administered by the Hudson's Bay Company, whose Columbia Department comprised most of the Oregon Country and extended considerably north into New Caledonia and beyond 54°40′N, with operations reaching to tributaries of the Yukon River.[2]

Early exploration

George Vancouver explored Puget Sound in 1792. Vancouver claimed it for Great Britain on 4 June 1792, naming it for one of his officers, Lieutenant Peter Puget. Alexander Mackenzie was the first European to cross North America by land north of Mexico since Cabeza de Vaca of the Narváez expedition.[3], arriving at Bella Coola on the what is now the Central Coast of British Columbia in 1793. From 1805 to 1806 Meriwether Lewis and William Clark scouted the territory for the United States on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. David Thompson, working for the Montreal-based North West Company, explored much of the region beginning in 1807, with his friend and colleague Simon Fraser following the Fraser River to its mouth in 1808, attempting to ascertain whether or not it was the Columbia, as had been theorized about it in its northern reaches through New Caledonia, where it was known by its Dakleh name as the "Tacoutche Tesse". Thompson was the first European to voyage down the entire length of Columbia River. Along the way, his party camped at the junction with the Snake River on July 9, 1811. He erected a pole and a notice claiming the country for Great Britain and stating the intention of the North West Company to build a trading post at the site. Later in 1811, on the same expedition, he finished his survey of the entire Columbia, arriving at a partially constructed Fort Astoria just two months after the departure of John Jacob Astor's ill-fated Tonquin.[4]

Name origin

The origin of the word Oregon is not known for certain. One theory is that French Canadian fur company employees called the Columbia River "hurricane river" le fleuve d'ouragan, because of the strong winds of the Columbia Gorge. George R. Stewart argued in a 1944 article in American Speech that the name came from an engraver's error in a French map published in the early 1700s, on which the Ouisiconsink (Wisconsin River) was spelled "Ouaricon-sint", broken on two lines with the -sint below, so that there appeared to be a river flowing to the west named "Ouaricon".[5][6] This theory was endorsed in Oregon Geographic Names as "the most plausible explanation".[7]

Territorial evolution

The Oregon Country was originally claimed by Great Britain, France, Russia, and Spain; the Spanish claim was later taken up by the United States. The extent of the region being claimed was vague at first, evolving over decades into the specific borders specified in the US-British treaty of 1818. The U.S. based its claim in part on Robert Gray's entry of the Columbia River in 1792 and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Great Britain based its claim in part on British overland explorations of the Columbia River by David Thompson and on prior discovery and exploration along the Coast. Spain's claim was based on the Inter caetera and Treaty of Tordesillas of 1493-94, as well as explorations the Pacific coast in the late 1700s.[8] Russia based its claim off its explorations and trading activities in the region and asserted its ownership of the region north of the 51st parallel by the Ukase of 1821, which was quickly challenged by the other powers and withdrawn to 54°40′N by separate treaties with the US and Britain in 1824 and 1825 respectively.[9] Spain gave up its claims of exclusivity via the Nootka Conventions of the 1790s. In the Nootka Conventions , which followed the Nootka Crisis Spain granted Britain rights to the Pacific Northwest, although it did not establish a northern boundary for Spanish California, nor did it extinguish Spanish rights to the Pacific Northwest.[10] Spain later relinquished any remaining claims to territory north of the 42nd parallel to the United States as part of the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819. In the 1820s Russia gave up its claims south of 54°40′ and east of the 141st meridian in separate treaties with the United States and Britain. [11]

Meanwhile, the United States and Britain negotiated the Anglo-American Convention of 1818 that extended the boundary between their territories west along the 49th parallel to the Rocky Mountains. The two countries agreed to "joint occupancy" of the land west of the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean.

In 1821, as part of the forced merger between the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company the British Parliament imposed the laws of Upper Canada on British subjects in Rupert's Land and Columbia District , and gave the authority to enforce those laws to the Hudson's Bay Company. John McLoughlin, as chief factor of Fort Vancouver, applied the law to British subjects and sought to maintain law and order over American settlers as well.

In 1843 settlers established their own government, called the Provisional Government of Oregon. A legislative committee drafted a code of laws known as the Organic Law. It included the creation of an executive committee of three, a judiciary, militia, land laws, and four counties. There was vagueness and confusion over the nature of the 1843 Organic Law, in particular whether it was a constitutional or statutory. In 1844 a new legislative committee decided to consider it statutory. The 1845 Organic Law made additional changes, including allowing the participation of British subjects in the government. Although the Oregon Treaty of 1846 settled the boundaries of US jurisdiction, the Provisional Government continued to function until 1849, when the first governor of Oregon Territory arrived.[12]

A faction of Oregon politicians hoped to continue Oregon's political evolution into an independent nation, but pressure to join the United States would prevail by 1848.[13]

Early settlement

Explorer David Thompson of the British-owned North West Company and later Hudson's Bay Company penetrated the Oregon Country from the north, via Athabasca Pass, arriving in 1807. In 1810, John Jacob Astor founded the Pacific Fur Company, which established a fur-trading post at Astoria, Oregon in 1811. Thompson traveling down the Columbia River reached the partially constructed Fort Astoria just two months after the departure of the ill-fated Tonquin. Along the way he had camped and claimed the land at the future Fort Nez Perces site at the confluence with the Snake River. This initiated a very brief era of competition between American and British fur traders. The Pacific Fur operation broke down during the War of 1812 and was sold to the North West Company. Under British control, Astoria was renamed Fort George.[14]

In 1821 when the North West Company was merged with the Hudson's Bay Company, the British Parliament imposed the laws of Upper Canada on British subjects in Columbia District and Rupert's Land, and gave the Hudson's Bay Company authority to enforce those laws. John McLoughlin was appointed head or Chief Factor of the Columbia Department in 1824. He moved its regional headquarters to Fort Vancouver, which became the de facto political center of the Pacific Northwest. McLoughlin applied the laws to British subjects, kept peace with the natives and sought to maintain law and order over American settlers as well.

Astor continued to compete for Oregon Country furs through his American Fur Company operations in the Rockies.[15] In the 1820s, a few American explorers and traders visited this land beyond the Rocky Mountains. Long after the Lewis & Clark Expedition and also after the consolidation of the fur trade in the region by the Canadian fur companies, American "Mountain Men" such as Jedediah Smith and Jim Beckwourth came roaming into and across the Rocky Mountains, following Indian trails through the Rockies to California and Oregon. They were looking for beaver pelts and other furs, which were had by trapping but difficult to obtain in the Oregon Country due to the policy of the Hudson's Bay Company of creating a "fur desert", via deliberate over-hunting in order to make the country's frontiers with the US unprofitable for American ventures.[16] The Mountain Men, like the Metis employees of the Canadian fur companies, adopted Indian ways and many of them married Indian women.

Reports of Oregon Country eventually circulated in the eastern United States. Some churches decided to send missionaries to convert the Indians. Jason Lee, a Methodist minister from New York, was the first Oregon missionary. He built a mission school for Indians in the Willamette Valley in 1834. Others followed within a few years.

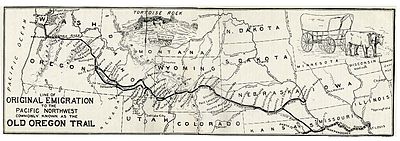

American settlers began to arrive from the east by the Oregon Trail starting in the late 1830s, and came in increasing numbers each subsequent year. Increased tension led to the Oregon boundary dispute. Both sides realized that settlers would ultimately decide who controlled the region. Belatedly, the Hudson's Bay Company, which had previously discouraged settlement as it conflicted with the lucrative fur trade, reversed their position. In 1841 James Sinclair guided more than 100 settlers from the Red River Colony to settle on HBC farms near Fort Vancouver, on orders from Sir George Simpson. The Sinclair expedition crossed the Rockies into the Columbia Valley, near present-day Radium Hot Springs, British Columbia, then traveled south-west down the Kootenai River and Columbia River following the southern portion of the well established York Factory Express trade route.

The Canadian effort proved to be too little, too late. For, in what was dubbed "The Great Migration of 1843" or the "Wagon Train of 1843",[17][18] an estimated 700 to 1000 emigrants left for Oregon. Britain ceded Columbia District south of the 49 parallel to the United States by the Oregon Treaty in 1846.

The Oregon Treaty

In 1843, settlers in the Willamette Valley established a provisional government at Champoeg, which was personally (but not officially) recognized by John McLoughlin of the Hudson's Bay Company in 1845.

Political pressure in the United States urged the occupation of all the Oregon Country. Expansionists in the American South wanted to annex Texas, while their counterparts in the Northeast wanted to annex the Oregon Country whole. It was seen as significant that the expansions be parallel, as the relative proximity to other states and territories made it appear likely that Texas would be pro-slavery and Oregon against slavery.

In the 1844 U.S. Presidential election, the Democrats called for expansion into both areas. After being elected, however, President James K. Polk supported the 49th parallel as a northern limit for U.S. annexation in Oregon Country. It was Polk's uncompromising support for the expansion into Texas and relative silence on the Oregon boundary dispute that led to the phrase "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight!", referring to the northern border of the region and often erroneously attributed to Polk's campaign. The goal of the slogan was to rally Southern expansionists (some of whom wanted to annex only Texas in an effort to tip the balance of slave/free states and territories in favor of slavery) to support the effort to annex Oregon Country, appealing to the popular belief in Manifest Destiny. The British government, meanwhile, sought control of all territory north of the Columbia River.

Despite the posturing, neither country really wanted to fight what would have been the third war in 70 years against the other. The two countries eventually came to a peaceful agreement in the 1846 Oregon Treaty that divided the territory west of the Continental Divide along the 49th parallel to Georgia Strait; with all of Vancouver Island remaining under British control. This border still divides British Columbia from neighboring Washington, Idaho, and Montana.

During the 1840s the HBC shifted its Columbia Department headquarters from Fort Vancouver to Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island. The plan to move to a more northerly location dated back to the 1820s. George Simpson was the main force behind the move north; John McLoughlin became the main hindrance. McLoughlin had devoted his life's work to the Columbia business and his personal interests were increasingly linked to the growing settlements in the Willamette Valley. He fought Simpson's proposals to move north, but in vain. By the time Simpson made the final decision, in 1842, to move the headquarters to Vancouver Island, he had many reasons for doing so. There was a dramatic decline in the fur trade across North America. In contrast the HBC was seeing increasing profits with coastal exports of salmon and lumber to Pacific markets such as Hawaii. Coal deposits on Vancouver Island had been discovered and steamships such as the Beaver had shown the growing value of coal, economically and strategically. A general HBC shift toward Pacific shipping and away from the interior of the continent made Victoria Harbour much more suitable than Fort Vancouver's location on the Columbia River. The Columbia Bar at the river's mouth was dangerous and routinely meant weeks or months of waiting for ships to cross. The largest ships could not enter the river at all. Finally, the growing numbers of American settlers along the lower Columbia gave Simpson reason to question the long term security of Fort Vancouver. He worried, rightfully so, that the final border resolution would not follow the Columbia River. By 1842 he thought it more likely that the US would at least demand Puget Sound, and the British government would accept a border as far north as the 49th parallel, excluding Vancouver Island. Despite McLoughlin's stalling, the HBC had begun the process of shifting away from Fort Vancouver and toward Vancouver Island and the northern coast in the 1830s. The increasing number of American settlers arriving in the Willamette Valley after 1840 served to make the need more pressing.[19]

In 1848, the U.S. portion of the Oregon Country was formally organized as the Oregon Territory. In 1849, Vancouver Island became a British Crown colony, with the mainland being organized into the colony of British Columbia in 1858. Shortly after the establishment of Oregon Territory there was an effort to split off the region north of the Columbia River, which resulted in the creation of Washington Territory in 1853.

Descriptions of the land and settlers

Alexander Ross, an early Scottish Canadian fur trader, describes the lower Columbia River area of the Oregon Country (known to him as the Columbia District):

"The banks of the river throughout are low and skirted in the distance by a chain of moderately high lands on each side, interspersed here and there with clumps of wide spreading oaks, groves of pine, and a variety of other kinds of woods. Between these high lands lie what is called the valley of the Wallamitte [sic], the frequented haunts of innumerable herds of elk and deer.... . In ascending the river the surrounding country is most delightful, and the first barrier to be meet with is about forty miles up from its mouth. Here the navigation is interrupted by a ledge of rocks, running across the river from side to side in the form of an irregular horseshoe, over which the whole body of water falls at one leap down a precipice of about forty feet, called the Falls."

After living in Oregon from 1843 to 1848, Peter H. Burnett wrote:

[Oregonians] were all honest, because there was nothing to steal; they were all sober, because there was no liquor to drink; there were no misers, because there was no money to hoard; and they were all industrious, because it was work or starve.[20][21]

See also

- Washington Territory

- Gray Sails the Columbia River

- New Albion

- Russo-American Treaty (1824)

- Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1825)

References

- ^ Meinig, D.W. (1995) [1968]. The Great Columbia Plain (Weyerhaeuser Environmental Classic ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-295-97485-0.

- ^ Mackie, Richard Somerset (1997). Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793-1843. Vancouver: University of British Columbia (UBC) Press. p. 284. ISBN 0-7748-0613-3.

- ^ DeVoto, Bernard (1953). The Journals of Lewis and Clark. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. xxix. ISBN 0-395-08380-X.

- ^ Nisbet, Jack (1994). Sources of the River: Tracking David Thompson Across Western North America. Sasquatch Books. pp. 4–5. ISBN 1-57061-522-5.

- ^ Stewart, George R. (1944). "The Source of the Name 'Oregon'". American Speech. 19 (2). Duke University Press: 115–117. doi:10.2307/487012. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ Stewart, George R. (1967) [1945]. Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States (Sentry edition (3rd) ed.). Houghton Mifflin. pp. 153, 463.

- ^ McArthur, Lewis A. (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names (Seventh ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87595-277-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Elliott, John Huxtable (2007). Empires of the Atlantic World. Yale University Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9780300123999. online at Google Books

- ^ Haycox, Stephen W. (2002). Alaska: An American Colony. University of Washington Press. pp. 1118–1122. ISBN 9780295982496.

- ^ Weber, David J. (1994). The Spanish Frontier in North America. Yale University Press. p. 287. ISBN 9780300059175. online at Google Books

- ^ Chiorazzi, Michael G. (2005). Prestatehood Legal Materials. Haworth Press. p. 959. ISBN 9780789020567.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) online at Google Books - ^ Chiorazzi, Michael G. (2005). Prestatehood Legal Materials. Haworth Press. pp. 959–962. ISBN 9780789020567.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) online at Google Books - ^ Clarke, S.A. (1905). Pioneer Days of Oregon History. J.K. Gill Company.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Meinig, D.W. (1995) [1968]. The Great Columbia Plain (Weyerhaeuser Environmental Classic ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-295-97485-0.

- ^ Mackie, Richard Somerset (1997). Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793-1843. Vancouver: University of British Columbia (UBC) Press. pp. 65, 108, 110–111. ISBN 0-7748-0613-3. online at Google Books

- ^ Mackie, Richard Somerset (1997). Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793-1843. Vancouver: University of British Columbia (UBC) Press. pp. 64–65, 259. ISBN 0-7748-0613-3. online at Google Books

- ^ The Wagon Train of 1843: The Great Migration. Oregon Pioneers. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ^ Events in The West: 1840-1850. PBS. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ^ Mackie, Richard Somerset (1997). Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793-1843. Vancouver: University of British Columbia (UBC) Press. pp. 240–245, 256–262, 264–273, 276. ISBN 0-7748-0613-3. online at Google Books

- ^ MacColl, E. Kimbark (1979). The Growth of a City: Power and Politics in Portland, Oregon 1915-1950. Portland, Oregon: The Georgian Press. ISBN 0960340815.

- ^ MacColl cites Peter H. Burnett, Recollections and Opinions of an Old Pioneer, New York 1880, pg 181.

External links

- Chronology of Oregon Events

- Convention Between Great Britain and Russia, 1825 (Treaty of St. Petersburg, 1825)