Jack Johnson (boxer)

Jack Johnson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | John Arthur Johnson March 31, 1878 |

| Died | June 10, 1946 (aged 68) |

| Nationality | |

| Other names | Galveston Giant |

| Statistics | |

| Weight(s) | Heavyweight |

| Height | 6 ft 1.5 in (187 cm) |

| Reach | 74 in (190 cm) |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 104 |

| Wins | 73 |

| Wins by KO | 40 |

| Losses | 13 |

| Draws | 9 |

| No contests | 9 |

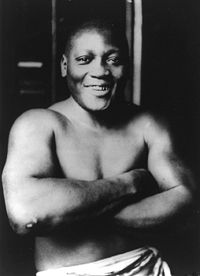

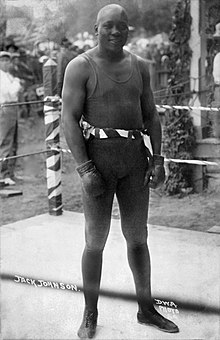

John Arthur ("Jack") Johnson (March 31, 1878 – June 10, 1946), nicknamed the “Galveston Giant”, was an American boxer, the first black world heavyweight boxing champion (1908-1915).

Early life

Johnson was born in Galveston, Texas, the third child and first son of Henry and Tina "Tiny" Johnson, former slaves who worked at blue-collar jobs to raise six children and taught them how to read and write. Jack Johnson had just five years of formal schooling. He dropped out of school after five or six years of education, to get a job as a dock worker in Galveston.

Professional boxing career

Johnson's boxing style was very distinctive. He developed a more patient approach than was customary in that day: playing defensively, waiting for a mistake, and then capitalizing on it. Johnson always began a bout cautiously, slowly building up over the rounds into a more aggressive fighter. He often fought to punish his opponents rather than knock them out, endlessly avoiding their blows and striking with swift counters. He always gave the impression of having much more to offer and, if pushed, he could punch powerfully.

Johnson's style was very effective, but it was criticized in the press as being cowardly and devious. By contrast, World Heavyweight Champion "Gentleman" [[James J. Corbett|Jim Corbett] had used many of the same techniques a decade earlier, and was praised by the press as "the cleverest man in boxing".[1] Corbett was white.

By 1902, Johnson had won at least 50 fights against both white and black opponents. Johnson won his first title on February 3, 1903, beating "Denver" Ed Martin over 20 rounds for the World Colored Heavyweight Championship. His efforts to win the full title were thwarted, as world heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries refused to face him then. Black and white boxers could meet in other competitions, but the world heavyweight championship was off limits to them. However, Johnson did fight former champion Bob Fitzsimmons in July 1907, and knocked him out in two rounds.[1]

Johnson finally won the world heavyweight title on December 26, 1908, when he fought the Canadian world champion Tommy Burns in Sydney, after stalking Burns around the world for two years and taunting him in the press for a match. The fight lasted fourteen rounds before being stopped by the police in front of over 20,000 spectators. The title was awarded to Johnson on a referee's decision as a T.K.O, but he had clearly beaten the champion.

After Johnson's victory over Burns, racial animosity among whites ran so deep that Jack London called out for a "Great White Hope" to take the title away from Johnson.[2] As title holder, Johnson thus had to face a series of fighters billed by boxing promoters as "great white hopes", often in exhibition matches. In 1909, he beat Frank Moran, Tony Ross, Al Kaufman, and the middleweight champion Stanley Ketchel. The match with Ketchel was keenly fought by both men until the 12th and last round, when Ketchel threw a right to Johnson's head, knocking him down. Slowly regaining his feet, Johnson threw a straight to Ketchel's jaw, knocking him out, along with some of his teeth, several of which "supposedly" were embedded in Johnson's glove. His fight with Philadelphia Jack O'Brien was a disappointing one for Johnson: though weighing 205 pounds (93 kg) to O'Brien's 161 pounds (73 kg), he could only achieve a six-round draw with the great middleweight.

The "Fight of the Century"

In 1910, former undefeated heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries came out of retirement and said, "I feel obligated to the sporting public at least to make an effort to reclaim the heavyweight championship for the white race. . . . I should step into the ring again and demonstrate that a white man is king of them all."[3] Jeffries had not fought in six years and had to lose weight to get back to his championship fighting weight.[4]

The fight took place on July 4, 1910 in front of 20,000 people, at a ring built just for the occasion in downtown Reno, Nevada. Johnson proved stronger and more nimble than Jeffries. In the 15th round, after Jeffries had been knocked down twice for the first time in his career, his people called it quits to prevent Johnson from knocking him out.

The "Fight of the Century" earned Johnson $65,000 and silenced the critics, who had belittled Johnson's previous victory over Tommy Burns as "empty," claiming that Burns was a false champion since Jeffries had retired undefeated.

Riots and aftermath

The outcome of the fight triggered race riots that evening — the Fourth of July — all across the United States, from Texas and Colorado to New York and Washington, D.C. Johnson's victory over Jeffries had dashed white dreams of finding a "great white hope" to defeat him. Many whites felt humiliated by the defeat of Jeffries.[clarification needed][1]

Blacks, on the other hand, were jubilant, and celebrated Johnson's great victory as a victory for racial advancement. Black poet William Waring Cuney later highlighted the black reaction to the fight in his poem "My Lord, What a Morning". Around the country, blacks held spontaneous parades and gathered in prayer meetings.

Some "riots" were simply blacks celebrating in the streets. In certain cities, like Chicago, the police did not disturb the celebrations. But in other cities, the police and angry white citizens tried to subdue the revelers. Police interrupted several attempted lynchings. In all, "riots" occurred in more than 25 states and 50 cities. About 23 blacks and two whites died in the riots, and hundreds more were injured.[5]

Film of the bout

A number of leading American film companies joined forces to shoot footage of the Jeffries-Johnson fight and turn it into a feature-length documentary film, at the cost of $250,000. The film was distributed widely in the U.S. and was exhibited internationally as well. As a result, Congress banned prizefight films from being distributed across state lines in 1912; the ban was lifted in 1940. In 2005, the film of the Jeffries-Johnson "Fight of the Century" was entered into the United States National Film Registry as being worthy of preservation.[6]

In the United States, many states and cities banned the exhibition of the Johnson-Jeffries film. The movement to censor Johnson's black supremacy took over the country within three days after the fight.[7] It was a spontaneous movement, mobilized by the Christian lobby and police forces, and endorsed by former President Theodore Roosevelt.[8]

Loss of the title

On April 5, 1915, Johnson lost his title to Jess Willard, a working cowboy from Kansas who did not start boxing until he was almost thirty years old. With a crowd of 25,000 at Oriental Park Racetrack in Havana, Cuba, Johnson was K.O.'d in the 26th round of the scheduled 45-round fight, which was co-promoted by Roderick James "Jess" McMahon and a partner. Johnson found that he could not knock out the giant Willard, who fought as a counterpuncher, making Johnson do all the leading. Johnson, aged 37, although having won almost every round, began to tire after the 20th round, and was visibly hurt by heavy body punches from Willard in rounds preceding the 26th round knockout. Johnson is said by many to have spread rumors that he took a dive,[9] but Willard is widely regarded as having won the fight outright. Willard said, "If he was going to throw the fight, I wish he'd done it sooner. It was hotter than hell out there".

In a famous photo showing Johnson lying on the mat after being knocked down and during the ten count, he can be seen shielding his eyes from the glare of the tropical sun with his glove.

Professional boxing record

| 73 Wins (40 knockouts, 30 decisions, 3 disqualifications), 13 Losses (7 knockouts, 5 decisions, 1 disqualification), 10 Draws, 5 No Contests [1] | |||||||

| Result | Record | Opponent | Type | Rd., Time | Date | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss | 73–13–10 | KO | 7 (10) | September 1, 1938 | |||

| Win | 73–12–10 | KO | 3 | November 29, 1932 | |||

| Win | 72–12–10 | KO | 2 | April 28, 1931 | |||

| Loss | 71–12–10 | Decision | 10 | March 4, 1931 | |||

| Loss | 71–11–10 | TKO | 6 (10) | May 15, 1928 | Johnson did not continue after the sixth round. | ||

| Loss | 71–10–10 | KO | 5 (10) | April 16, 1928 | Wright's real name was Ed Wright. | ||

| Loss | 71–9–10 | Decision | 10 | September 6, 1926 | |||

| Loss | 71–8–10 | Decision | 10 | July 1, 1926 | |||

| Loss | 71–7–10 | TKO | 7 (12) | May 30, 1926 | Johnson did not continue after the seventh round. | ||

| Win | 71–6–10 | Decision | 15 | May 2, 1926 | |||

| Win | 70–6–10 | Decision | 10 | February 22, 1924 | |||

| Win | 69–6–10 | Decision | 12 | May 20, 1923 | |||

| Win | 68–6–10 | KO | 4 | May 6, 1923 | Lodge's real name was Walter Fakeskie. | ||

| Win | 67–6–10 | KO | 5 | May 28, 1921 | |||

| Win | 66–6–10 | KO | 6 | April 15, 1921 | |||

| Win | 65–6–10 | Decision | 4 | November 25, 1920 | |||

| Win | 64–6–10 | KO | 6 (6) | November 25, 1920 | |||

| Win | 63–6–10 | KO | 3 | September 28, 1920 | |||

| Win | 62–6–10 | KO | 3 | April 18, 1920 | |||

| Win | 61–6–10 | KO | 6 (25) | September 28, 1919 | |||

| Win | 60–6–10 | KO | 15 (15) | August 10, 1919 | |||

| Win | 59–6–10 | Decision | 10 | June 22, 1919 | |||

| Win | 58–6–10 | KO | 2 | February 12, 1919 | |||

| Win | 57–6–10 | Decision | 4 | April 3, 1918 | |||

| Win | 56–6–10 | KO | 6 (20) | April 23, 1916 | |||

| Win | 55–6–10 | TKO | Unknown | March 23, 1916 | |||

| Loss | 54–6–10 | KO | 26 (45), 1:26 | April 5, 1915 | Lost World Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 54–5–10 | KO | 3 (10) | December 15, 1914 | |||

| Win | 53–5–10 | Decision | 20 | June 27, 1914 | Retained World Heavyweight title. | ||

| Draw | 52–5–10 | Draw | 10 | December 19, 1913 | Retained World Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 52–5–9 | TKO | 9 (45) | July 4, 1912 | Retained World Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 51–5–9 | TKO | 15 (45), 2:20 | July 4, 1910 | Retained World Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 50–5–9 | KO | 12 (15) | October 16, 1909 | Retained World Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 49–5–9 | Decision | 10 | September 9, 1909 | Retained World Heavyweight title. Decision given in an Associated Press report. | ||

| Win | 48–5–9 | Decision | 6 | June 30, 1909 | Retained World Heavyweight title. Decision given by The Washington Post. | ||

| Draw | 47–5–9 | Draw | 6 | May 19, 1909 | Retained World Heavyweight title. Newspapers reported differing results. | ||

| Win | 47–5–8 | Decision | 14 | December 26, 1908 | Won World Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 46–5–8 | TKO | 8 (20) | July 31, 1908 | |||

| Win | 45–5–8 | KO | 11 (45), 1:30 | November 6, 1907 | |||

| Win | 44–5–8 | Decision | 6 | September 12, 1907 | Decision given by the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette. | ||

| Win | 43–5–8 | KO | 1 | August 28, 1907 | |||

| Win | 42–5–8 | KO | 2 (6) | July 17, 1907 | |||

| Win | 41–5–8 | TKO | 9 (20) | March 4, 1907 | |||

| Win | 40–5–8 | KO | 1 (20) | February 19, 1907 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Draw | 39–5–8 | Decision | 10 | November 26, 1906 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 39–5–7 | Decision | 6 | November 8, 1906 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. Decision given by the Philadelphia Item. | ||

| Win | 38–5–7 | Decision | 6 | September 20, 1906 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. Decision given by the Kennebec Journal. | ||

| Draw | 37–5–7 | Draw | 10 | September 3, 1906 | |||

| Win | 37–5–6 | KO | 2 (12) | June 18, 1906 | |||

| Win | 36–5–6 | Decision | 15 | April 26, 1906 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 35–5–6 | KO | 7 (10) | April 16, 1906 | Black Bill's real name was Claude Brooks. | ||

| Win | 34–5–6 | Decision | 15 | March 14, 1906 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 33–5–6 | KO | 1 (10) | January 26, 1906 | |||

| Win | 32–5–6 | Decision | 3 | January 16, 1906 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. Decision given by the Boston Globe. | ||

| NC | 31–5–6 | No decision | 6 | December 2, 1905 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 31–5–6 | Decision | 12 | December 1, 1905 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. Decision given by the Durango Democrat and New York World. | ||

| Loss | 30–5–6 | Disqualification | 2 | November 25, 1905 | World Colored Heavyweight title was on the line. Johnson continued to claim the title due to losing by disqualification. | ||

| Win | 30–4–6 | Decision | 6 | July 24, 1905 | Decision given by the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette. | ||

| Win | 29–4–6 | Disqualification | 7 (15) | July 18, 1905 | Ferguson was disqualified for delivering a knee twice to Johnson's groin. | ||

| Win | 28–4–6 | Decision | 3 | July 13, 1905 | |||

| Win | 27–4–6 | KO | 1 (3) | July 13, 1905 | |||

| Win | 26–4–6 | Decision | 6 | June 26, 1905 | Decision given by the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette. | ||

| NC | 25–4–6 | No decision | 6 | May 19, 1905 | |||

| Win | 25–4–6 | KO | 3 | May 9, 1904 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Draw | 24–4–6 | Draw | 3 | May 9, 1904 | The fight was declared even by both the New York World and Washington Times. | ||

| Win | 24–4–5 | KO | 4 (6) | May 2, 1904 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 23–4–5 | KO | 4 (6) | April 25, 1905 | |||

| Loss | 22–4–5 | Decision | 20 | March 28, 1905 | |||

| Win | 22–3–5 | KO | 2 (20) | October 18, 1904 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 21–3–5 | Decision | 6 | June 2, 1904 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 20–3–5 | KO | 20 (20) | April 22, 1904 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 19–3–5 | Decision | 6 | February 15, 1904 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. Decision given by the Philadelphia Item. | ||

| NC | 18–3–5 | No contest | 5 | February 6, 1904 | The referee left the ring claiming the fighters were "faking". | ||

| Win | 18–3–5 | Decision | 20 | December 11, 1903 | |||

| Win | 17–3–5 | Decision | 20 | October 27, 1903 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 16–3–5 | Decision | 6 | July 31, 1903 | Decision given by the New York World. | ||

| Win | 15–3–5 | KO | 3 | May 11, 1903 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 14–3–5 | Decision | 10 | April 16, 1903 | |||

| Win | 13–3–5 | Decision | 20 | February 26, 1903 | Retained World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 12–3–5 | Decision | 20 | February 5, 1903 | Won World Colored Heavyweight title. | ||

| Win | 11–3–5 | Disqualification | 8 | December 4, 1902 | Russell was disqualified for several low blows. | ||

| Win | 10–3–5 | Decision | 20 | October 31, 1902 | |||

| Win | 9–3–5 | TKO | 12 | October 21, 1902 | |||

| Win | 8–3–5 | Decision | 20 | September 3, 1902 | |||

| Draw | 7–3–5 | Draw | 20 | June 20, 1902 | |||

| Win | 7–3–4 | KO | 5 | May 16, 1902 | |||

| Win | 6–3–4 | KO | 4 (15) | March 7, 1902 | |||

| Win | 5–3–4 | KO | 10 | February 7, 1902 | |||

| Draw | 4–3–4 | Draw | 15 | December 27, 1901 | |||

| Loss | 4–3–3 | Decision | 20 | November 4, 1901 | |||

| Draw | 4–2–3 | Draw | 10 | April 26, 1901 | |||

| Loss | 4–2–2 | KO | 3 (20) | May 25, 1901 | |||

| Draw | 4–1–2 | Draw | 7 | January 14, 1901 | |||

| Win | 4–1–1 | TKO | 14 (20) | December 27, 1900 | Klondike's real name was John Haines. | ||

| Draw | 3–1–1 | Draw | 20 | June 25, 1900 | |||

| Win | 3–1 | Disqualification | 6 (20) | April 20, 1900 | |||

| NC | 2–1 | No decision | 4 | April 9, 1900 | |||

| NC | 2–1 | No decision | 15 | March 21, 1900 | |||

| Loss | 2–1 | TKO | 5 (6) | May 8, 1899 | |||

| Win | 2–0 | KO | 5 | November 20, 1897 | Retained Texas State Middleweight title. | ||

| Win | 1–0 | KO | 2 (15) | November 1, 1897 | Won Texas State Middleweight title. | ||

Personal life

Johnson was an early example of the celebrity athlete in the modern era, appearing regularly in the press and later on radio and in motion pictures. He earned considerable sums endorsing various products, including patent medicines, and indulged several expensive hobbies such as automobile racing and tailored clothing, as well as purchasing jewelry and furs for his wives.[10] He even challenged champion racer Barney Oldfield to a match auto race at the Sheepshead Bay, New York one mile (1.6 km) dirt track. Oldfield, far more experienced, easily out-distanced Johnson, ending any thoughts the boxer might have had about becoming a professional driver.[11] Once, when he was pulled over for a $50 speeding ticket (a large sum at the time), he gave the officer a $100 bill; the officer protested that he couldn't make change for that much, Johnson told him to keep the change, as he was going to make his return trip at the same speed.[1] Johnson was also interested in opera (his favorite being Il Trovatore) and in history — he was an admirer of Napoleon Bonaparte, believing him to have risen from a similar origin to his own. In 1920, Johnson opened a night club in Harlem; he sold it three years later to a gangster, Owney Madden, who renamed it the Cotton Club.

Johnson constantly flouted conventions regarding the social and economic "place" of Blacks in American society. As a Black man, he broke a powerful taboo in consorting with White women, and would constantly and arrogantly verbally taunt men (both white and black) inside and outside the ring. Johnson was pompous about his affection for white women, and imperious about his physical prowess, both in and out of the ring. Asked the secret of his staying power by a reporter who had watched a succession of women parade into, and out of, the champion's hotel room, Johnson supposedly said "Eat jellied eels and think distant thoughts".[12]

Johnson was married three times. All of his wives were white, a fact that caused considerable controversy at the time. In January 1911, Johnson married Etta Terry Duryea. A Brooklyn socialite and former wife of businessman Charles Duryea, she met Johnson at a car race in 1909. Their romantic involvement was very turbulent. Beaten many times by Johnson and suffering from severe depression, she committed suicide in September 1912, shooting herself with a revolver.[13]

Less than three months later, on 4 December 1912, Johnson married Lucille Cameron. After Johnson married Cameron, two ministers in the South recommended that Johnson be lynched. Cameron divorced him in 1924 because of infidelity.

The next year, Johnson married Irene Pineau. When asked by a reporter at Johnson's funeral what she had loved about him, she replied, "I loved him because of his courage. He faced the world unafraid. There wasn't anybody or anything he feared."[13] Johnson had no children.

Prison sentence

On October 18, 1912, Johnson was arrested on the grounds that his relationship with Lucille Cameron violated the Mann Act against "transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes" due to her being a prostitute. Cameron, soon to become his second wife, refused to cooperate and the case fell apart. Less than a month later, Johnson was arrested again on similar charges. This time the woman, another prostitute named Belle Schreiber with whom he had been involved in 1909 and 1910, testified against him, and he was convicted by a jury in June 1913. The conviction was despite the fact that the incidents used to convict him took place prior to passage of the Mann Act.[1] He was sentenced to a year and a day in prison.

Johnson skipped bail, and left the country, joining Lucille in Montreal on June 25, before fleeing to France. For the next seven years, they lived in exile in Europe, South America and Mexico. Johnson returned to the U.S. on 20 July 1920. He surrendered to Federal agents at the Mexican border and was sent to the United States Penitentiary, Leavenworth to serve his sentence. He was released on July 9, 1921.[1]

There have been recurring proposals to grant Johnson a posthumous presidential pardon. A bill requesting President George W. Bush to pardon Johnson in 2008, passed the House, but failed to pass in the Senate.[14] In April 2009, Senator John McCain, along with Representative Peter King, filmmaker Ken Burns and Johnson's great niece, Linda Haywood, requested a presidential pardon for Johnson from President Barack Obama.[15] On July 29, 2009, Congress passed a resolution calling on President Obama to issue a pardon.[16]

While incarcerated, Johnson found need for a tool that would help tighten loosened fastening devices, and modified a wrench for the task. He patented his improvements on April 18, 1922, as US Patent 1,413,121.[17]

Later life

Johnson continued fighting, but age was catching up with him. He fought professionally until 1938, losing 7 of his last 9 bouts, losing his final fight to Walter Price, by a 7th-round TKO.

On June 10, 1946, Johnson died due to a car crash on U.S. Highway 1 near Franklinton, North Carolina, a small town near Raleigh, North Carolina, after racing angrily from a diner that refused to serve him.[18] He was taken to the closest black hospital, Saint Agnes Hospital in Raleigh. He was 68 years old at the time of his death. He was buried next to Etta Duryea Johnson at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago. His grave was initially unmarked, but a stone that bears only the name "Johnson" now stands above the plots of Jack, Etta, and Irene Pineau.

Legacy

Johnson was inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1954, and is on the roster of both the International Boxing Hall of Fame and the World Boxing Hall of Fame. In 2005, the United States National Film Preservation Board deemed the film of the 1910 Johnson-Jeffries fight "historically significant" and put it in the National Film Registry.

Johnson's skill as a fighter and the money that it brought made it impossible for him to be ignored by the establishment. In the short term, the boxing world reacted against Johnson's legacy. But Johnson foreshadowed, in many ways, perhaps one of the most famous boxers of all time, Muhammad Ali. In fact, Ali often spoke of how he was influenced by Jack Johnson. Ali identified with Johnson because he felt America ostracized him in the same manner because of his opposition to the Vietnam War and affiliation with the Nation of Islam.[19] In his autobiography, Ali relates how he and Joe Frazier agreed that Johnson and Joe Louis were the greatest boxers of all.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Jack Johnson on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[20]

In September, 2008, 62 years after Johnson's death, the United States Congress passed a resolution to recommend that the President grant a pardon for his 1913 conviction, in acknowledgment of its racist overtones, and in order to exonerate Johnson and recognize his contribution to boxing.[21] In April 2009, John McCain of Arizona joined Representative Peter T. King of New York in a call for a posthumous pardon for the boxing legend by President Barack Obama.[22]

In connection with his conviction on charges of violating the Mann Act, it has been pointed out that "[i]f Johnson did not violate the actual letter of the law, he certainly violated its spirit repeatedly as he openly consorted with prostitutes and, in one insistence, bankrolled a former madam, who had been one of his personal favorites, when she was seeking start up capital to open her own fully furnished brothel."[23]

Popular culture

Johnson's story is the basis of the play and subsequent 1970 movie The Great White Hope, starring James Earl Jones as Johnson (known as Jack Jefferson in the movie), and Jane Alexander as his love interest. In 2005, filmmaker Ken Burns produced a 2-part documentary about Johnson's life, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, based on the 2004 nonfiction book of the same name by Geoffrey C. Ward.

Folksinger and blues musician Leadbelly references Johnson in a song about the Titanic: “Jack Johnson wanna get on board, Captain said I ain't hauling no coal. Fare thee, Titanic, fare thee well. When Jack Johnson heard that mighty shock, mighta seen the man do the Eagle rock. Fare thee, Titanic, fare thee well” (The Eagle Rock was a popular dance at the time). In 1969, American folk singer Jamie Brockett reworked the Leadbelly song into a satirical talking blues called "The Legend of the U.S.S. Titanic". It should be noted there is no convincing evidence that Johnson was in fact refused passage on the Titanic because of his race, as these songs allege.

Miles Davis's 1970 (see 1970 in music) album A Tribute to Jack Johnson was inspired by Johnson. The end of the record features the actor Brock Peters (as Johnson) saying:

I'm Jack Johnson. Heavyweight champion of the world. I'm black. They never let me forget it. I'm black all right! I'll never let them forget it!

Miles Davis and Wynton Marsalis both have done soundtracks for documentaries about Johnson. Several hip-hop activists have also reflected on Johnson's legacy, most notably in the album The New Danger, by Mos Def, in which songs like "Zimzallabim" and "Blue Black Jack" are devoted to the artist's pugilistic hero. Additionally, both Southern punk rock band This Bike Is A Pipe Bomb and alternative country performer Tom Russell have songs dedicated to Johnson. Russell's piece is both a tribute and a biting indictment of the racism Johnson faced: “here comes Jack Johnson, like he owns the town, there's a lot of white Americans like to see a man go down… like to see a black man drown.”

Johnson was referenced in the film Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy and he is mentioned in the 1940 book Native Son by author Richard Wright. Furthermore, 41st street in Galveston is named Jack Johnson Blvd.

Jack Johnson, the American singer, was named after this guy.

Wal-Mart created a controversy in 2006 when DVD shoppers were directed from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Planet of the Apes to the "similar item" Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson.[24]

Ray Emery of the Philadelphia Flyers of the NHL sported a mask with a picture of Johnson on it as a tribute to his love for boxing.

In the trenches of World War One Johnson's name was used by British troops to describe German 15cm heavy artillery shells that produced a lot of black smoke:[25] a "Jack Johnson" was big and black and knocked you to the ground.

In Joe R. Lansdale's short story The Big Blow, Johnson is featured fighting a white boxer brought in by Galveston, Texas's boxing fans to defeat the African American fighter during the 1900 Galveston Hurricane. The story won a Bram Stoker Award and was expanded into a novel.[26]

Johnson is the subject of the biographical comic book The Original Johnson, by writer/artist Trevor Von Eeden.[27]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Ken Burns, Unforgivable Blackness

- ^ Flatter, Ron "Johnson boxed, lived on own terms"

- ^ Orbach, Barak "The Johnson-Jeffries Fight and Censorship of Black Supremacy"

- ^ Orbach, Barak "The Johnson-Jeffries Fight and Censorship of Black Supremacy"

- ^ New York tribune .p.2 July 5, 1910 for accounts of post fighting riots

- ^ Library of Congress "National Film Registry 2005"

- ^ Orbach, Barak "The Johnson-Jeffries Fight and Censorship of Black Supremacy"

- ^ Orbach, Barak "The Johnson-Jeffries Fight and Censorship of Black Supremacy"

- ^ http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1070658/3/index.htm

- ^ Papa Jack, Jack Johnson and the Era of the White Hopes, Randy Roberts, Macmillan, 1983, page 132.

- ^ Barney Oldfield, The Life and Times of America's Speed King, William Nolan, Brown Fox Books, 2002.

- ^ Stump, Al. 'The rowdy reign of the Black avenger'. True: The Men's Magazine January 1963.

- ^ a b Jack's women

- ^ http://www.cnn.com/2008/CRIME/09/26/pardon.request.ap/index.html[dead link]

- ^ McCain calls for pardon for first black heavyweight champion Retrieved on 2009-04-01.

- ^ http://www.thesweetscience.com/boxing-article/7058/congress-passes-jack-johnson-resolution/

- ^ http://inventors.about.com/od/wstartinventions/ss/wrench.htm

- ^ "Two champs meet", U.S.News & World Report, L.P., 2005-01-09. Retrieved on August 30, 2008

- ^ http://www.biographyonline.net/sport/muhammad_ali.html

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ^ Pardon sought for black US boxer

- ^ Posthumous pardon sought for Johnson

- ^ Throwing in the Towel: The Factual Jack Johnson vs. the Fictional Jack Johnson

- ^ Horowitz, Adam, et al. "101 Dumbest Moments in Business", CNN.com, 2007-01-23. Retrieved on January 23, 2007

- ^ Firstworldwar.com: Jack Johnson

- ^ "1997 Bram Stoker Awards"

- ^ Glenn Hauman. "Helping out Peter David and Bob Greenberger" glennhauman.com; April 17, 2009

External links

- Boxing record for Jack Johnson from BoxRec (registration required)

- Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, a 2 part film by Ken Burns and PBS 2005.

- Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, A Review on Ken Burns' Documentary.

- Extended biography of Jack Johnson

- "The Johnson-Jeffries Fight and Censorship of Black Supremacy", by Barak Orbach.

- Famous Texans - Jack Johnson

- John (Jack) Arthur Johnson

- Harlem 1900-1940: Schomburg Exhibit Jack Johnson

- ESPN.com: Jack Johnson

- Cyber Boxing Zone - Jack Johnson

- Interview with Jack Johnson biographer Geoffery C. Ward

- CBS News - A Pardon for Jack Johnson

- Jack Johnson's Gravesite

- http://www.johnsonjeffries2010.com/index.php

- African American boxers

- Burials at Graceland Cemetery (Chicago)

- History of racism in the United States

- International Boxing Hall of Fame inductees

- Racially motivated violence against African Americans

- People from Galveston, Texas

- Road accident deaths in North Carolina

- Vaudeville performers

- People convicted of violating the Mann Act

- World Heavyweight Champions

- 1878 births

- 1946 deaths

- United States National Film Registry films