Hanami

Hanami (花見, lit. "flower viewing") is the Japanese traditional custom of enjoying the beauty of flowers, "flower" in this case almost always meaning cherry blossoms or ume blossoms.[1] From the end of March to early May, sakura bloom all over Japan.[2] The blossom forecast (桜前線, sakurazensen, literally cherry blossom front) is announced each year by the weather bureau, and is watched carefully by those planning hanami as the blossoms only last a week or two. In modern-day Japan, hanami mostly consists of having an outdoor party beneath the sakura during daytime or at night. Hanami at night is called yozakura (夜桜, literally night sakura). In many places such as Ueno Park temporary paper lanterns are hung for the purpose of yozakura.

A more ancient form of hanami also exists in Japan, which is enjoying the plum blossoms (梅 ume) instead. This kind of hanami is popular among older people, because they are more calm than the sakura parties, which usually involve younger people and can sometimes be very crowded and noisy.

History

The practice of hanami is many centuries old. The custom is said to have started during the Nara Period (710–794) when it was ume blossoms that people admired in the beginning. But by the Heian Period (794–1185), sakura came to attract more attention and hanami was synonymous with sakura.[3] From then on, in tanka and haiku, "flowers" meant "sakura."

Hanami was first used as a term analogous to cherry blossom viewing in the Heian era novel Tale of Genji. Whilst a wisteria viewing party was also described, from this point on the terms "hanami" and "flower party" were only used to describe cherry blossom viewing.

Sakura originally was used to divine that year's harvest as well as announce the rice-planting season. People believed in kami inside the trees and made offerings. Afterwards, they partook of the offering with sake.

Emperor Saga of the Heian Period adopted this practice, and held flower-viewing parties with sake and feasts underneath the blossoming boughs of sakura trees in the Imperial Court in Kyoto. Poems would be written praising the delicate flowers, which were seen as a metaphor for life itself, luminous and beautiful yet fleeting and ephemeral. This was said to be the origin of hanami in Japan.

The custom was originally limited to the elite of the Imperial Court, but soon spread to samurai society and, by the Edo period, to the common people as well. Tokugawa Yoshimune planted areas of cherry blossom trees to encourage this. Under the sakura trees, people had lunch and drank sake in cheerful feasts.

Today, the Japanese people continue the tradition of hanami, gathering in great numbers wherever the flowering trees are found. Thousands of people fill the parks to hold feasts under the flowering trees, and sometimes these parties go on until late at night. In more than half of Japan, the cherry blossoming period coincides with the beginning of the scholastic and fiscal years, and so welcoming parties are often opened with hanami. The Japanese people continue the tradition of hanami by taking part in the processional walks through the parks. This is a form of retreat for contemplating and renewing their spirits.

The teasing proverb dumplings rather than flowers (花より団子, hana yori dango) hints at the real priorities for most cherry blossom viewers, meaning that people are more interested in the food and drinks accompanying a hanami party than actually viewing the flowers themselves.[4][5] (A punning variation, Boys Over Flowers (花より男子, Hana Yori Dango), is the title of a manga and anime series.)

Dead bodies are buried under the cherry trees! is a popular saying about hanami, after the opening sentence of the 1925 short story "Under the Cherry Trees" by Motojirō Kajii.

Emperor Saga (嵯峨天皇 Saga-tennō) (786-842) of the Heian Period adopted this custom, and celebrated parties to view the flowers with sake and feasts under the blossoming branches of sakura trees in the Imperial Court in Kyoto. This was said to be the origin of hanami in Japan.[6] Poems were written praising the delicate flowers, which were seen as a metaphor for life itself; beautiful, but lasting for a very short time. This "temporary" view of life is very popular in Japanese culture and is usually considered as an admirable form of existence; for example, in the samurai's principle of life ending when it's still beautiful and strong, instead of slowly getting old and weak. The Heian era poets used to write poems about how much easier things would be in Spring without the sakura blossoms, because their existence reminded us that life is very short:

| If there were no cherry blossoms in this world How much more tranquil our hearts would be in Spring. |

||

Hanami was used as a term that meant "cherry blossom viewing" for the first time in the Heian era novel Tale of Genji (chapter 8, 花宴 Hana no En, "Under the Cherry Blossoms").[8] From then on, in tanka (短歌) and in haiku (俳句) poetry, "flowers" meant "sakura", and the terms "hanami" and "flower party" were only used to mean sakura blossom viewing.[9] At the beginning, the custom was followed only by the Imperial Court, but the samurai nobility also began celebrating it during the Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1568-1600). In those years, Toyotomi Hideyoshi gave great hanami parties in Yoshino and Daigo, and the festivity became very popular through all the Japanese society.[10] Shortly after that, farmers began their own custom of climbing nearby mountains in the springtime and having lunch under the blooming cherry trees. This practice, called then as the "spring mountain trip", combined itself with that of the nobles' to form the urban culture of hanami.[11] By the Edo Period (1600-1867), all the common people took part in the celebrations, in part because Tokugawa Yoshimune planted areas of cherry blossom trees to encourage this. Under the sakura trees, people had lunch and drank sake in cheerful feasts.[12][13]

Today

The Japanese people continue the tradition of hanami, gathering in great numbers wherever the flowering trees are found. Thousands of people fill the parks to hold feasts under the flowering trees, and sometimes these parties go on until late at night. In more than half of Japan, the cherry blossoming days come at the same time of the beginning of school and work after vacation, and so welcoming parties are often opened with hanami. Usually, people go to the parks to keep the best places to celebrate hanami with friends, family, and company broken coworkers many hours or even days before. In cities like Tokyo, it's also common to have celebrations under the sakura at night. Hanami at night is called yozakura (夜桜, literally "night sakura"). In many places such as Ueno Park, temporary paper lanterns are hung to have yozakura.

The blossom forecast (桜前線 sakurazensen, literally "cherry blossom front") is announced each year by the Japan Meteorological Agency,[14] and is watched with attention by those who plan to celebrate hanami because the blossoms last for very little time, usually no more than two weeks. The first cherry blossoms happen in the subtropical southern islands of Okinawa, while on the northern island of Hokkaido, they bloom much later. In most large cities like Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka, the cherry blossom season normally takes place around the end of March and the beginning of April. The television and newspapers closely follow this "cherry blossom front", as it slowly moves from South to North.[15]

The hanami celebrations usually involve eating and drinking, and playing and listening music. Some special dishes are prepared and eaten at the occasion, like dango and bento, and it's common for sake to be drunk as part of the festivity. The proverb "dumplings rather than flowers" (花より団子 hana yori dango) makes fun of people who prefer to eat and drink instead of admiring the blossoms. "Dead bodies are buried under the cherry trees!" (桜の樹の下には屍体が埋まっている! Sakura no ki no shita ni wa shitai ga umatte iru!) is a popular saying about hanami, after the first line of the 1925 short story "Under the Cherry Trees" by Motojirō Kajii.[16][17]

Outside Japan

Hanami festivities have also become popular outside of Japan in the last years, and is also celebrated today at other countries. Smaller hanami celebrations in Korea, Philippines and China (where the custom was first created) also take place traditionally.[18]

In the United States, hanami has also become very popular. In 1912, Japan gave 3,000 sakura trees as a gift to the United States to celebrate the nations' friendship. These trees were planted in Washington, D.C., and another 3,800 gifted trees were also taken there in 1956. These sakura trees continue to be a popular tourist attraction, and every year, the "National Cherry Blossom Festival" takes place when they bloom in early Spring.[19]

In Macon, Georgia, another cherry blossom festival called the "International Cherry Blossom Festival" is celebrated every Spring. Macon is known as the "Cherry Blossom Capital of the World", because 300,000 sakura trees grow there.[20]

In Brooklyn, New York, the "Annual Sakura Matsuri Cherry Blossom Festival" takes place in May, at Brooklyn Botanic Garden.[21] This festivity has been celebrated since 1981, and is one of the Garden's most famous attractions. Similar celebrations are also done in Philadelphia[22] and other places through the United States.

Gallery

-

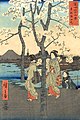

"Yoshitsune and Benkei Viewing Cherry Blossoms", by artist Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, 1885

-

Hanami party at Odawara Castle.

-

Sakura trees with paper lanterns in Tokyo.

-

Sakura trees in Washington, D.C.

-

International Cherry Blossom Festival in Macon, Georgia, United States.

See also

- Sakura

- International Cherry Blossom Festival

- Momijigari—autumn leaf viewing

- National Cherry Blossom Festival

- Subaru Cherry Blossom Festival of Greater Philadelphia

- Tsukimi—moon viewing

References

- ^ Sosnoski, Daniel (1996). Introduction to Japanese culture. Tuttle Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 0804820562.

- ^ "Cherry blossom forecast" (in Japanese). Weather Map.

- ^ Brooklyn Botanic Garden (2006). Mizue Sawano: The Art of the Cherry Tree. Brooklyn Botanic Garden. p. 12. ISBN 1889538256.

- ^ Buchanan, Daniel Crump (1973). Japanese Proverbs and Sayings. University of Oklahoma Pres. p. 175. ISBN 0806110821.

- ^ Trimnell, Edward (2004). Tigers, Devils, and Fools: A Guide to Japanese Proverbs. Beechmont Crest Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 0974833029.

- ^ Varley, Paul (2000). Japanese Culture (4th ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2152-4. pp. pp. 75-78.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Cherry Blossom Viewing". Japan Mint. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ Shikibu, Murasaki (2006). The Tale of Genji. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-303949-0. pp. pp. 86-87.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Tetsuya, Ito. "Genji Monogatari" (in Japanese). The Japanese Literature Project online. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ Varley, Paul (2000). Japanese Culture (4th ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2152-4. pp. pp. 75-79.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Varley, Paul (2000). Japanese Culture (4th ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2152-4. pp. p. 79.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "MIT Japanese: Culture notes - Ohanami". Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ^ Varley, Paul (2000). Japanese Culture (4th ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2152-4. pp. pp. 79-80.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Japanese Culture - Calendar - Hanami Season". JapanZone. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ Akasegawa, Gempei (2000). Sennin no sakura, zokujin no sakura: Nippon kaibo kiko (in Japanese). JTB Nihon Kotsu Kosha Shuppan Jigyokyoku. ISBN 978-4-533-01983-8. "As cherry blossom front comes up, the whole Japan goes into a war; we just can't sit home and let it go". Cited at Cyber Sakura Watching, Osaka Seikei University, Kyoto, Japan.

{{cite book}}: External link in|publisher=|publisher=(help) - ^ "Cyber Sakura Watching". Osaka Seikei University, Kyoto, Japan. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ^ Gessel, Van C. (1993). The Showa Anthology: Modern Japanese Short Stories. Kodansha International. ISBN 4-7700-1708-1. pp. p. 24.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Spring flower festival events". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ ""National Cherry Blossom Festiva"". Official Site. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ ""International Cherry Blossom Festival Online"". Official Site. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ "Brooklyn Botanic Garden Celebrates Hanami". Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Brooklyn, New York. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ^ "Subaru Cherry Blossom Festival of Greater Philadelphia". Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

External links

- Hanami in Philadelphia! Information on the Subaru Cherry Blossom Festival of Greater Philadelphia

- Hanami in Japan! Information on Hanami and other annual events across Japan.

- Hanami Fun Facts — Japanzine:Field Guide to Japan by Zack Davisson

- Hanami Manners 101 — Japanzine by Emily Millar

- Kyotoview — Hanami In Kyoto