Spanish Armada

| Battle of Gravelines hi mama i love you | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish War | |||||||

The Spanish Armada and English ships in August 1588, by unknown painter (English School, 16th century). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Lord Howard of Effingham Francis Drake | Duke of Medina Sidonia | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

34 warships[1] 163 armed merchant vessels (30 over 200 tons)[1] 30 flyboats |

22 Spanish and Portuguese galleons 108 armed merchant vessels[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Battle of Gravelines: 50–100 dead[3] 400 wounded 8 fireships burnt[4] Disease: 6,000-8,000 dead |

Battle of Gravelines: Over 600 dead 800 wounded[5] 397 captured 2 ships sunk[citation needed] Storms/Disease: 51 ships wrecked 10 ships scuttled[6] 20,000 dead[7] | ||||||

The Spanish Armada (Spanish: Grande y Felicísima Armada, "Great and Most Fortunate Navy") was the Spanish fleet that sailed against England under the command of the Duke of Medina Sidonia in 1588, with the intention of overthrowing Elizabeth I of England to stop English involvement in the Spanish Netherlands and English privateering in the Atlantic. The fleet's mission was to sail to the Gravelines in Flanders and transport an army under the Duke of Parma across the Channel to England. The mission eventually failed due to early English attacks on the Armada, especially during the Battle of Gravelines, strategic errors by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, and bad weather. The campaign formed part of a nearly twenty-year-long Anglo-Spanish war.

Background

Philip II of Spain had been co-monarch of England until the death of his wife Mary I in 1558. A devout Roman Catholic, he considered his Protestant half sister-in-law Elizabeth a heretic and illegitimate ruler of England. He had previously supported plots to have her overthrown in favour of her Catholic cousin and heir presumptive, Mary, Queen of Scots, but was thwarted when Elizabeth had Mary imprisoned, and finally executed in 1587. In addition, Elizabeth, who sought to advance the cause of Protestantism where possible, had supported the Dutch Revolt against Spain. In retaliation, Philip planned an expedition to invade England so as to overthrow the Protestant regime of Elizabeth, thereby ending the English material support for the United Provinces— that part of the Low Countries that had successfully seceded from Spanish rule — and cutting off English attacks of Spanish trade and settlements[8] in the New World. The king was supported by Pope Sixtus V, who treated the invasion as a crusade, with the promise of a subsidy should the Armada make land.[9]

The Armada's appointed commander was the highly experienced Álvaro de Bazán, but he died in February 1588 and Medina Sidonia, a high-born courtier with no experience at sea, took his place. The fleet set out with 22 warships of the Spanish Royal Navy and 108 converted merchant vessels, with the intention of sailing through the English Channel to anchor off the coast of Flanders, where the Duke of Parma's army of tercios would stand ready for an invasion of the south east of England.

The Armada achieved its first goal and anchored outside Gravelines, at the coastal border area between France and the Spanish Netherlands. While awaiting communications from Parma's army, it was driven from its anchorage by an English fire ship attack, and in the ensuing naval battle at Gravelines the Spanish were forced to abandon their rendezvous with Parma's army.

The Armada managed to regroup and withdraw north, with the English fleet harrying it for some distance up the east coast of England. A return voyage to Spain was plotted, and the fleet sailed north of Scotland, into the Atlantic and past Ireland, but severe storms disrupted the fleet's course. More than 24 vessels were wrecked on the north and western coasts of Ireland, with the survivors having to seek refuge in Scotland. Of the fleet's initial complement, about 50 vessels failed to make it back to Spain. The expedition was the largest engagement of the undeclared Anglo–Spanish War (1585–1604).

History

Planned invasion of England

This article or section appears to contradict itself. (August 2010) |

Prior to the undertaking, Pope Sixtus V allowed Philip II of Spain to collect crusade taxes and granted his men indulgences. The blessing of the Armada's banner on 25 April 1588 was similar to the ceremony used prior to the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. On 28 May 1588, the Armada set sail from Lisbon (occupied Portugal), headed for the English Channel. The fleet was composed of 151 ships, 8,000 sailors and 18,000 soldiers, and bore 1,500 brass guns and 1,000 iron guns. The full body of the fleet took two days to leave port. It contained 28 purpose-built warships: twenty galleons, four galleys and four (Neapolitan) galleasses. The remainder of the heavy vessels consisted mostly of armed carracks and hulks; there were also 34 light ships present.

In the Spanish Netherlands 30,000 soldiers[citation needed] awaited the arrival of the armada, the plan being to use the cover of the warships to convey the army on barges to a place near London. All told, 55,000 men were to have been mustered, a huge army for that time. On the day the Armada set sail, Elizabeth's ambassador in the Netherlands, Dr Valentine Dale, met Parma's representatives in peace negotiations, and the English made a vain effort to intercept the Armada in the Bay of Biscay.

On 16 July negotiations were abandoned, and the English fleet stood prepared, if ill-supplied, at Plymouth, awaiting news of Spanish movements. The English fleet outnumbered the Spanish, with 200 to 130 ships,[10] while the Spanish fleet outgunned the English—its available firepower was 50% more than that of the English.[11] The English fleet consisted of the 34 ships of the royal fleet (21 of which were galleons of 200 to 400 tons), and 163 other ships, 30 of which were 200 to 400 tons and carried up to 42 guns each; 12 of these were privateers owned by Lord Howard of Effingham, Sir John Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake.[1]

The Armada was delayed by bad weather, forcing the four galleys and one of the galleons to leave the fleet, and was not sighted in England until 19 July, when it appeared off The Lizard in Cornwall. The news was conveyed to London by a system of beacons that had been constructed all the way along the south coast. On that evening the English fleet was trapped in Plymouth Harbour by the incoming tide. The Spanish convened a council of war, where it was proposed to ride into the harbour on the tide and incapacitate the defending ships at anchor and from there to attack England; but Medina Sidonia declined to act, because this had been explicitly forbidden by Philip, and chose to sail on to the east and toward the Isle of Wight. Soon afterwards, 55 English ships set out to confront them from Plymouth under the command of Lord Howard of Effingham, with Sir Francis Drake as Vice Admiral. Howard ceded some control to Drake, given his experience in battle, and the Rear Admiral was Sir John Hawkins.

The next night, in order to execute their attack, the English tacked upwind of the Armada, thus gaining the weather gage, a significant advantage. Over the next week there followed two inconclusive engagements, at Eddystone and the Isle of Portland. Two Spanish ships, the carrack Rosario and the galleon San Salvador, were abandoned after they collided. When night fell, Francis Drake turned his ship back to loot the ships, capturing supplies of much-needed gunpowder, and gold. However, Drake had been guiding the English fleet by means of a lantern. After he snuffed out the lantern and slipped away for the abandoned Spanish ships, the rest of his fleet became scattered, and was in complete disarray by dawn. It took an entire day for the English fleet to regroup. The English ships then used their superior speed and manoeuvrability to catch up with the Spanish fleet after a day of sailing. At the Isle of Wight the Armada had the opportunity to create a temporary base in protected waters of the Solent and wait for word from Parma's army. In a full-scale attack, the English fleet broke into four groups — Martin Frobisher of the HMS Aid now also being given command over a squadron — with Drake coming in with a large force from the south. At the critical moment Medina Sidonia sent reinforcements south and ordered the Armada back to open sea to avoid sandbanks. There were no secure harbours nearby, so the Armada was compelled to make for Calais, without regard to the readiness of Parma's army.

On 27 July, the Armada anchored off Calais in a tightly packed defensive crescent formation, not far from Dunkirk, where Parma's army, reduced by disease to 16,000, was expected to be waiting, ready to join the fleet in barges sent from ports along the Flemish coast. Communications had proven to be far more difficult than anticipated, and it only now became clear that this army had yet to be equipped with sufficient transport or assembled in port, a process which would take at least six days, while Medina Sidonia waited at anchor; and that Dunkirk was blockaded by a Dutch fleet of thirty flyboats under Lieutenant-Admiral Justin of Nassau. Parma desired that the Armada send its light petaches to drive away the Dutch, but Medina Sidonia could not do this because he feared that he might need these ships for his own protection. There was no deepwater port where the fleet might shelter — always acknowledged as a major difficulty for the expedition — and the Spanish found themselves vulnerable as night drew on. At midnight on 28 July, the English set alight eight fireships, sacrificing regular warships by filling them with pitch, brimstone, some gunpowder and tar, and cast them downwind among the closely anchored vessels of the Armada. The Spanish feared that these uncommonly large fireships were "hellburners",[12] specialised fireships filled with large gunpowder charges, which had been used to deadly effect at the Siege of Antwerp. Two were intercepted and towed away, but the remainder bore down on the fleet. Medina Sidonia's flagship and the principal warships held their positions, but the rest of the fleet cut their anchor cables and scattered in confusion. No Spanish ships were burnt, but the crescent formation had been broken, and the fleet now found itself too far to leeward of Calais in the rising southwesterly wind to recover its position. The English closed in for battle.

Battle of Gravelines

The small port of Gravelines was then part of Flanders in the Spanish Netherlands, close to the border with France and the closest Spanish territory to England. Medina Sidonia tried to re-form his fleet there and was reluctant to sail further east knowing the danger from the shoals off Flanders, from which his Dutch enemies had removed the sea marks.

The English had learned more of the Armada's strengths and weaknesses during the skirmishes in the English Channel and had concluded it was necessary to close within 100 yards to penetrate the oak hulls of the Spanish ships. They had spent most of their gunpowder in the first engagements and had after the Isle of Wight been forced to conserve their heavy shot and powder for a final attack near Gravelines. During all the engagements, the Spanish heavy guns could not easily be run in for reloading because of their close spacing and the quantities of supplies stowed between decks, as Francis Drake had discovered on capturing the damaged Rosario in the Channel.[13] Instead the cannoneers fired once and then jumped to the rigging to attend to their main task as marines ready to board enemy ships. In fact, evidence from Armada wrecks in Ireland shows that much of the fleet's ammunition was never spent.[14] Their determination to thrash out a victory in hand-to-hand fighting proved a weakness for the Spanish; it had been effective on occasions such as the Battle of Lepanto and the Battle of Ponta Delgada (1582), but the English were aware of this strength and sought to avoid it by keeping their distance.

With its superior maneuverability, the English fleet provoked Spanish fire while staying out of range. The English then closed, firing repeated and damaging broadsides into the enemy ships. This also enabled them to maintain a position to windward so that the heeling Armada hulls were exposed to damage below the water line. Many of the gunners were killed or wounded, and the Spanish ships had more priests on board than trained gunners, so the task of manning the cannons often fell to the regular foot soldiers on board, who did not know how to operate the complex cannons. Sailors positioned on the upper decks of the English and Spanish ships were able to exchange musket fire, as their ships were in proximity. After eight hours, the English ships began to run out of ammunition, and some gunners began loading objects such as chains into cannons. Around 4:00 PM, the English fired their last shots and were forced to pull back.[15]

Five Spanish ships were lost. The galleass San Lorenzo ran aground at Calais and was taken by Howard after murderous fighting between the crew, the galley slaves, the English and the French who ultimately took possession of the wreck. The galleons San Mateo and San Felipe drifted away in a sinking condition, ran aground on the island of Walcheren the next day, and were taken by the Dutch. One carrack ran aground near Blankenberge; another foundered. Many other Spanish ships were severely damaged, especially the Spanish and Portuguese Atlantic-class galleons which had to bear the brunt of the fighting during the early hours of the battle in desperate individual actions against groups of English ships. The Spanish plan to join with Parma's army had been defeated and the English had afforded themselves some breathing space. But the Armada's presence in northern waters still posed a great threat to England.

Tilbury speech

On the day after the battle of Gravelines, the wind had backed southerly, enabling Medina Sidonia to move his fleet northward away from the French coast. Although their shot lockers were almost empty, the English pursued in an attempt to prevent the enemy from returning to escort Parma. On 2 August Old Style (12 August New Style) Howard called a halt to the pursuit in the latitude of the Firth of Forth off Scotland. By that point, the Spanish were suffering from thirst and exhaustion, and the only option left to Medina Sidonia was to chart a course home to Spain, by a very hazardous route.

The threat of invasion from the Netherlands had not yet been discounted by the English, and Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester maintained a force of 4,000 soldiers at West Tilbury, Essex, to defend the Thames Estuary against any incursion up river towards London.

On 8 August (Old Style) (18 August New Style) Queen Elizabeth went to Tilbury to encourage her forces, and the next day gave to them what is probably her most famous speech:

"My loving people, we have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit ourselves to armed multitudes for fear of treachery; but, I do assure you, I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear, I have always so behaved myself, that under God I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and goodwill of my subjects; and, therefore, I am come amongst you as you see at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of battle, to live or die amongst you all — to lay down for my God, and for my kingdoms, and for my people, my honour and my blood even in the dust. I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king — and of a King of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which, rather than any dishonour should grow by me, I myself will take up arms — I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field. I know already, for your forwardness, you have deserved rewards and crowns, and, we do assure you, on the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you."[16]

Return to Spain

This article or section appears to contradict itself. (August 2010) |

In September 1588 the Armada sailed around Scotland and Ireland into the North Atlantic. The ships were beginning to show wear from the long voyage, and some were kept together by having their hulls bundled up with cables. Supplies of food and water ran short, and the cavalry horses were cast overboard into the sea. The intention would have been to keep well to the west of the coast of Scotland and Ireland, in the relative safety of the open sea. However, there being at that time no way of accurately measuring longitude, the Spanish were not aware that the Gulf Stream was carrying them north and east as they tried to move west, and they eventually turned south much further to the east than planned, a devastating navigational error. Off the coasts of Scotland and Ireland the fleet ran into a series of powerful westerly gales, which drove many of the damaged ships further towards the lee shore. Because so many anchors had been abandoned during the escape from the English fireships off Calais, many of the ships were incapable of securing shelter as they reached the coast of Ireland and were driven onto the rocks. The late 16th century, and especially 1588, were marked by unusually strong North Atlantic storms, perhaps associated with a high accumulation of polar ice off the coast of Greenland, a characteristic phenomenon of the "Little Ice Age."[17] As a result many more ships and sailors were lost to cold and stormy weather than in combat.

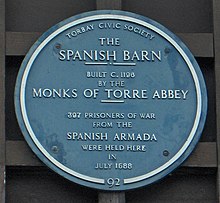

Following the gales it is reckoned that 5,000 men died, whether by drowning and starvation or by slaughter at the hands of English forces after they were driven ashore in Ireland; only half of the Spanish Armada fleet returned back home to Spain.[18] Reports of the passage around Ireland abound with strange accounts of brutality and survival and attest to the qualities of the Spanish seamanship.[19] Some survivors were concealed by Irish people, but few shipwrecked Spanish survived to be taken into Irish service, fewer still to return home.

In the end, 67 ships and around 10,000 men survived. Many of the men were near death from disease, as the conditions were very cramped and most of the ships ran out of food and water. Many more died in Spain, or on hospital ships in Spanish harbours, from diseases contracted during the voyage. It was reported that, when Philip II learned of the result of the expedition, he declared, "I sent the Armada against men, not God's winds and waves". Greatly disappointed, he still forgave Medina Sidonia.[20]

Aftermath

English losses stood at 50-100 dead and 400 wounded, and none of their ships had been sunk. But after the victory, typhus, dysentery and hunger killed many sailors and troops (estimated at 6,000–8,000) as they were discharged without pay: a demoralising dispute occasioned by the government's fiscal shortfalls left many of the English defenders unpaid for months, which was in contrast to the assistance given by the Spanish government to its surviving men.

Although the English fleet was unable to prevent the regrouping of the Armada at the Battle of Gravelines, requiring it to remain on duty even as thousands of its sailors died, the outcome vindicated the strategy adopted, resulting in a revolution in naval warfare with the promotion of gunnery, which until then had played a supporting role to the tasks of ramming and boarding. The battle of Gravelines is regarded by some specialists in military history as reflecting a lasting shift in the naval balance in favour of the English, in part because of the gap in naval technology and armament it confirmed between the two nations,[21] which continued into the next century. In the words of Geoffrey Parker, by 1588 'the capital ships of the Elizabethan navy constituted the most powerful battlefleet afloat anywhere in the world.'[22]

In England, the boost to national pride lasted for years, and Elizabeth's legend persisted and grew long after her death. The repulse of Spanish naval might gave heart to the Protestant cause across Europe, and the belief that God was behind the Protestant cause was shown by the striking of commemorative medals that bore the inscription, He blew with His winds, and they were scattered. There were also more lighthearted medals struck, such as the one with the play on Julius Caesar's words: Venit, Vidit, Fugit (he came, he saw, he fled). The victory was acclaimed by the English as their greatest since Agincourt.[citation needed]

However, an attempt to press home the English advantage failed the following year, when the Drake–Norris Expedition of 1589, with a comparable fleet of English privateers, sailed to establish a base in the Azores, attack Spain, and raise a revolt in Portugal.[8] The Norris–Drake Expedition or Counter Armada raided Corunna, but withdrew from Lisbon after failing to co-ordinate its strategy effectively with the Portuguese.

The Spanish Navy underwent a major organisational reform that helped it to maintain control over its own home waters and ocean routes into the next century. High seas buccaneering and the supply of troops to Philip II's enemies in the Netherlands and France continued, but brought few tangible rewards for England.[23] The Anglo-Spanish War dragged on to a stalemate that left Spain's power weakened, but its possessions in Europe and the Americas intact.

In popular culture

The preparations of the Armada and the Battle of Gravelines form the backdrop of two graphic novels in Bob de Moors "Cori le Moussaillon" (Les Espions de la Reine and Le Dragon des Mers'). In them, Cori the cabin boy works as a spy in the Armada for the English.

The Armada and intrigues surrounding its threat to England form the backdrop of the films Fire Over England (1937), with Laurence Olivier and Flora Robson, and The Sea Hawk with Errol Flynn.

The Battle of Gravelines and the subsequent chase around the northern coast of Scotland form the climax of Charles Kingsley's 1855 novel Westward Ho!, which in 1925 became the first novel to be adapted into a radio drama by BBC.[24]

The Battle of Gravelines is the climax of the 2007 film, Elizabeth: The Golden Age starring Cate Blanchett and Clive Owen.

In the twentieth season of The Simpsons, an episode depicts the reason for the Armada's attack as Queen Elizabeth's rebuff of the King of Spain. Homer Simpson accidentally sets the only English ship on fire; then collides with the Armada, setting all their ships on fire, creating victory for England.

The Final Jeopardy! response on May 20, 2009 on Jeopardy! was "The Spanish Armada". The clue was "It was the 'they' in the medal issued by Elizabeth I reading, 'God breathed and they were scattered.'"

See also

- English Armada

- Black Legend

- Spanish Armada in Ireland

- Francisco de Cuellar

- Fernando Sánchez de Tovar – Landed Castilian forces in England

- Carlos de Amésquita – Landed Spanish forces in England

- Spanish Empire

Other meanings

- In Tennis slang, Spanish Armada is used to refer to the group of highly ranked Spanish players, such as Rafael Nadal, Fernando Verdasco, Feliciano López, David Ferrer, Tommy Robredo, Nicolás Almagro, Felix Mantilla, Albert Portas, Juan Carlos Ferrero, Carlos Moyá, and others. It is also the nickname for their Davis Cup team.

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c Colin Martin, Geoffrey Parker,The Spanish Armada, Penguin Books, 1999, ISBN 1 901341 14 3, p. 40.

- ^ Colin Martin, Geoffrey Parker,The Spanish Armada, Penguin Books, 1999, ISBN 1 901341 14 3, pp.10, 13, 19, 26.

- ^ Lewis, Michael.The Spanish Armada, New York: T.Y. Crowell Co., 1968, p. 184.

- ^ John Knox Laughton,State Papers Relating to the Defeat of the Spanish Armada, Anno 1588, printed for the Navy Records Society, MDCCCXCV, Vol. II, pp. 8–9, Wynter to Walsyngham: indicates that the ships used as fire-ships were drawn from those at hand in the fleet and not hulks from Dover.

- ^ Lewis, p. 182.

- ^ Lewis p. 208

- ^ Lewis p. 208-9

- ^ a b Hart, Francis Rußel, Admirals of the Caribbean, Hougton Mifflin Co., 1922, pp. 28–32, describes a large privateer fleet of 25 ships commanded by Drake in 1585 that raided about the Spanish Caribbean colonies.

- ^

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "The Spanish Armada". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. "…the widespread suffering and irritation caused by the religious wars Elizabeth fomented, and the indignation caused by her religious persecution, and the execution of Mary Stuart, caused Catholics everywhere to sympathise with Spain and to regard the Armada as a crusade against the most dangerous enemy of the Faith." and "Pope Sixtus V agreed to renew the excommunication of the queen, and to grant a large subsidy to the Armada, but given the time needed for preparation and actual sailing of the fleet, would give nothing till the expedition should actually land in England. In this way he eventually was saved the million crowns, and did not take any proceedings against the heretic queen."

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "The Spanish Armada". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. "…the widespread suffering and irritation caused by the religious wars Elizabeth fomented, and the indignation caused by her religious persecution, and the execution of Mary Stuart, caused Catholics everywhere to sympathise with Spain and to regard the Armada as a crusade against the most dangerous enemy of the Faith." and "Pope Sixtus V agreed to renew the excommunication of the queen, and to grant a large subsidy to the Armada, but given the time needed for preparation and actual sailing of the fleet, would give nothing till the expedition should actually land in England. In this way he eventually was saved the million crowns, and did not take any proceedings against the heretic queen."

- ^ http://britishbattles.com/spanish-war/spanish-armada.htm

- ^ Colin Martin, Geoffrey Parker,The Spanish Armada, Penguin Books, 1999, ISBN 1 901341 14 3, p. 185.

- ^ Template:PDFlink.

- ^ Coote, Stephen (2003). Drake. London: Simon & Schuster UK. p. 259. ISBN 0-7432-2007-2. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Colin Martin, Geoffrey Parker,The Spanish Armada, Penguin Books, 1999, ISBN 1 901341 14 3, pp.189–190

- ^ Battlefield Britain: Episode 4, the Spanish Armada

- ^ Damrosh, David, et al. The Longman Anthology of British Literature, Volume 1B: The Early Modern Period. Third ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2006

- ^ Brian Fagan, The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850,. New York: Basic Books, 2000

- ^ Garrett Mattingly, The Armada, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1959, p.369, the English Lord Deputy's orders were for the English soldiers in Ireland to kill Spanish prisoners which was done on several occasions.

- ^ Winston S. Churchill, The New World, vol. 3 of A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, (1956) Dodd, Mead & Co., New York, p. 130.

- ^ SparkNotes: Queen Elisabeth – Against the Spanish Armada

- ^ Aubrey N. Newman, David T. Johnson, P.M. Jones (1985) The Eighteenth Century Annual Bulletin of Historical Literature 69 (1), 93–109 doi:10.1111/j.1467-8314.1985.tb00698.

- ^ Geoffrey Parker, 'The Dreadnought Revolution of Tudor England', Mariner's Mirror, 82 (1996): 273.

- ^ Richard Holmes 2001, p. 858: "The 1588 campaign was a major English propaganda victory, but in strategic terms it was essentially indecisive"

- ^ Briggs, Asa. The BBC: The First Fifty Years. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1985. 63.

Bibliography

- Corbett, Julian S. Drake and the Tudor Navy: With a History of the Rise of England as a Maritime Power (1898) online edition vol 1; also online edition vol 2

- Cruikshank, Dan: Invasion: Defending Britain from Attack, Boxtree Ltd, 2002 ISBN 0752220291

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. The Spanish Armada: The Experience of War in 1588. (1988). 336 pp.

- Froude, James Anthony. The Spanish Story of the Armada, and Other Essays (1899), by a leading historian of the 1890s full text online

- Kilfeather T.P: Ireland: Graveyard of the Spanish Armada, Anvil Books Ltd, 1967

- Knerr, Douglas. "Through the "Golden Mist": a Brief Overview of Armada Historiography." American Neptune 1989 49(1): 5-13. Issn: 0003-0155

- Konstam, Angus. The Spanish Armada: The Great Enterprise against England 1588 (2009)

- Lewis, Michael. The Spanish Armada, New York: T.Y. Crowell Co., 1968.

- McDermott, James. England and the Spanish Armada: The Necessary Quarrel (2005) excerpt and text search

- Martin, Colin, and Geoffrey Parker. The Spanish Armada (2nd ed. 2002), 320pp by leading scholars; uses archaeological studies of some of its wrecked ships excerpt and text search

- Martin, Colin (with appendices by Wignall, Sydney: Full Fathom Five: Wrecks of the Spanish Armada (with appendices by Sydney Wignall), Viking, 1975

- Mattingly, Garrett. The Armada (1959). the classic narrative excerpt and text search

- Parker, Geoffrey. "Why the Armada Failed." History Today 1988 38(may): 26-33. Issn: 0018-2753. Summary by leadfing historian.

- Pierson, Peter. Commander of the Armada: The Seventh Duke of Medina Sidonia. (1989). 304 pp.

- Rasor, Eugene L. The Spanish Armada of 1588: Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. (1992). 277 pp.

- Rodger, N. A. M. The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain 660-1649 vol 1 (1999) 691pp; excerpt and text search

- Rodriguez-Salgado, M. J. and Adams, Simon, eds. England, Spain, and the Gran Armada, 1585-1604 (1991) 308 pp.

- Thompson, I. A. A. "The Appointment of the Duke of Medina Sidonia to the Command of the Spanish Armada", The Historical Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2. (1969), pp. 197–216. in JSTOR

- Alcalá-Zamora, José N. (2004). La empresa de Inglaterra: (la "Armada invencible" : fabulación y realidad). Taravilla: Real Academia de la Historia ISBN 9788495983374

Popular studies

- The Confident Hope of a Miracle. The True History of the Spanish Armada, by Neil Hanson, Knopf (2003), ISBN 1-4000-4294-1.

- Holmes, Richard. The Oxford Campanion to Military History. Oxford University Press. 2001. ISBN 978-0198606963

- From Merciless Invaders: The Defeat of the Spanish Armada, Alexander McKee, Souvenir Press, London, 1963. Second edition, Grafton Books, London, 1988.

- The Spanish Armadas, Winston Graham, Dorset Press, New York, 1972.

- Mariner's Mirror, Geoffrey Parker, 'The Dreadnought Revolution of Tudor England', 82 (1996): pp. 269–300.

- The Spanish Armada, Michael Lewis (1960). First published Batsford, 1960 – republished Pan, 1966

- Armada: A Celebration of the Four Hundredth Anniversary of the Defeat of the Spanish Armada, 1588-1988 (1988) ISBN 0-575-03729-6

- England and the Spanish Armada (1990) ISBN 0-7317-0127-5

- The Enterprise of England (1988) ISBN 0-86299-476-4

- The Return of the Armadas: the Later Years of the Elizabethan War against Spain, 1595–1603, RB Wernham ISBN 0-19-820443-4

- The Voyage of the Armada: The Spanish Story, David Howarth (1981) ISBN 0-00-211575-1

- T.P.Kilfeather Ireland: Graveyard of the Spanish Armada (Anvil Books, 1967)

- Winston Graham The Spanish Armadas (1972; reprint 2001) ISBN 0-14-139020-4

- Historic Bourne etc., J.J. Davies (1909)

External links

- The Defeat of the Spanish Armada. Insight into the context, personalities, planning and consequences. Wes Ulm

- English translation of Francisco de Cuellar's account of his service in the Armada and on the run in Ireland

- Elizabeth I and the Spanish Armada – a learning resource and teachers notes from the British Library

- Writing the Armada: myth, monumentalism and the transformation of event into national epic in Elizabethan literature - An essay by the Gibraltar writer and academic Dr. M. G. Sanchez

- The story of the Armada battles with pictures from the House of Lords tapestries

- Top Ten Myths and Muddles. Wes Ulm.

- Dutch Republic and the links from it give an insight into the politics in the Netherlands which ran parallel with political developments in England.

- BBC-ZDF etc. TV coproduction Natural History of Europe

- Discovery Civilization Battlefield Detectives – What Sank The Armada?