Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus | |

|---|---|

Posthumous portrait of Christopher Columbus by Sebastiano del Piombo. There are no known authentic portraits of Columbus. | |

| Born | Between 22 August and 31 October 1451 |

| Died | 20 May 1506 (aged 54) |

| Nationality | Genoese |

| Other names | Genoese: Christoffa Corombo Italian: Cristoforo Colombo Catalan: Cristòfor Colom Spanish: Cristóbal Colón Portuguese: Cristóvão Colombo Latin: Christophorus Columbus |

| Occupations | Maritime explorer for the Crown of Castile |

| Title | Admiral of the Ocean Sea; Viceroy and Governor of the Indies |

| Spouse | Filipa Moniz Perestrelo (c. 1455-1485) |

| Partner | Beatriz Enríquez de Arana (c. 1485-1506) |

| Children | Diego Fernando |

| Relatives | Giovanni Pellegrino, Giacomo and Bartholomew Columbus (brothers) |

| Signature | |

| |

Christopher Columbus (c. 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator from the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy,[1][2][3][4] whose voyages across the Atlantic Ocean led to general European awareness of the American continents in the Western Hemisphere. With his four voyages of exploration and several attempts at establishing a settlement on the island of Hispaniola, all funded by Isabella I of Castile, he initiated the process of Spanish colonization which foreshadowed general European colonization of the "New World".

Although Columbus was not the first explorer to reach the Americas from Europe (being preceded by the Norse led by Leif Ericson[5]), the voyages of Columbus molded the future of European colonization and encouraged European exploration of foreign lands for centuries to come.[citation needed]

Columbus' initial 1492 voyage came at a critical time of emerging modern western imperialism and economic competition between developing kingdoms seeking wealth from the establishment of trade routes and colonies. In this sociopolitical climate, Columbus' far-fetched scheme won the attention of Isabella I of Castile. Severely underestimating the circumference of the Earth, he estimated that a westward route from Iberia to the Indies would be shorter than the overland trade route through Arabia. If true, this would allow Spain entry into the lucrative spice trade—heretofore commanded by the Arabs and Italians. Following his plotted course, he instead landed within the Bahamas Archipelago at a locale he named San Salvador. Mistaking the lands he encountered for Asia, he referred to the inhabitants as "indios" (Spanish for "Indians").[6][7][8]

Early life

The name Christopher Columbus is the Anglicisation of the Latin Christophorus Columbus. His name in Italian is Cristoforo Colombo and in Spanish it is Cristóbal Colón. Columbus was born between 25 August and 31 October 1451 in Genoa, part of modern Italian Republic.[9] His father was Domenico Colombo, a middle-class wool weaver who worked both in Genoa and Savona and who also owned a cheese stand at which young Christopher worked as a helper. Christopher's mother was Susanna Fontanarossa. Bartolomeo, Giovanni Pellegrino and Giacomo were his brothers. Bartolomeo worked in a cartography workshop in Lisbon for at least part of his adulthood.[10]

Columbus never wrote in his native language, which is presumed to have been a Genoese variety of Ligurian. In one of his writings, Columbus claims to have gone to the sea at the age of 10. In 1470 the Columbus family moved to Savona, where Domenico took over a tavern. In the same year, Columbus was on a Genoese ship hired in the service of René I of Anjou to support his attempt to conquer the Kingdom of Naples. Some modern historians have argued that Columbus was not from Genoa, but instead, from Catalonia,[11] Portugal,[12] or Spain.[13] These competing hypotheses have generally been discounted by mainstream scholars.

In 1473 Columbus began his apprenticeship as business agent for the important Centurione, Di Negro and Spinola families of Genoa. Later he allegedly made a trip to Chios, a Genoese colony in the Aegean Sea.[14] In May 1476, he took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry a valuable cargo to northern Europe. He docked in Bristol, England;[15] Galway, Ireland and was possibly in Iceland in 1477. In 1479 Columbus reached his brother Bartolomeo in Lisbon, while continuing trading for the Centurione family. He married Filipa Moniz Perestrelo, daughter of the Porto Santo governor and Portuguese nobleman of Genoese origin Bartolomeu Perestrello. In 1479 or 1480, his son Diego Columbus was born. Between 1482 and 1485 Columbus traded along the coasts of West Africa, reaching the Portuguese trading post of Elmina at the Guinea coast.[16] Some records report that Filipa died in 1485. It is also speculated that Columbus may have simply left his first wife. In either case Columbus found a mistress in Spain in 1487, a 20-year-old orphan named Beatriz Enríquez de Arana.[17]

Intelligent and ambitious, Columbus eventually learned Latin, as well as Portuguese and Castilian, and read widely about astronomy, geography, and history, including the works of Ptolemy, Cardinal Pierre d'Ailly's Imago Mundi, the travels of Marco Polo and Sir John Mandeville, Pliny's Natural History, and Pope Pius II's Historia Rerum Ubique Gestarum. According to historian Edmund Morgan,

Columbus was not a scholarly man. Yet he studied these books, made hundreds of marginal notations in them and came out with ideas about the world that were characteristically simple and strong and sometimes wrong, the kind of ideas that the self-educated person gains from independent reading and clings to in defiance of what anyone else tries to tell him.[18]

Throughout his life, Columbus also showed a keen interest in the Bible and in biblical prophecies, and would often quote biblical texts in his letters and logs. For example, part of the argument that he submitted to the Spanish Catholic Monarchs when he sought their support for his proposed expedition to reach the Indies by sailing west was based on his reading of the Second Book of Esdras (see 2 Esdras 6:42, which Columbus took to mean that the Earth is made of six parts of land to one of water). Towards the end of life, Columbus produced a Book of Prophecies in which his career as an explorer is interpreted in the light of Christian eschatology and of apocalypticism.[10]

Quest for Asia

Background

Under the hegemony over Asia of the Mongol Empire (the so-called Pax Mongolica, or Mongol peace) Europeans had long enjoyed a safe land passage, the so-called "Silk Road", to China and India, which were sources of valuable goods such as silk, spices, and opiates. With the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the land route to Asia became much more difficult and dangerous. Portuguese navigators, under the leadership of King John II, sought to reach Asia by sailing around Africa. Major progress in this quest was achieved in 1488, when Bartolomeu Dias reached the Cape of Good Hope, in what is now South Africa. Meanwhile, in the 1480s the Columbus brothers had developed a different plan to reach the Indies (then construed roughly as all of south and east Asia) by sailing west across the "Ocean Sea", i.e., the Atlantic.

Geographical considerations

Washington Irving's 1828 biography of Columbus popularized the idea that Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan because Christian theologians insisted that the Earth was flat.[20] In fact, most educated Westerners had understood that the Earth was spherical at least since the time of Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC and whose works were widely studied and revered in Medieval Europe.[21] The sphericity of the Earth is also accounted for in the work of Ptolemy, on which ancient astronomy was largely based. Christian writers whose works clearly reflect the conviction that the Earth is spherical include Saint Bede the Venerable in his Reckoning of Time, written around AD 723. In Columbus' time, the techniques of celestial navigation, which use the position of the Sun and the Stars in the sky, together with the understanding that the Earth is a sphere, were beginning to be widely used by mariners.

Where Columbus did differ from the view accepted by scholars in his day was in his estimate of the westward distance from Europe to Asia. Columbus' ideas in this regard were based on three factors: his low estimate of the size of the Earth, his high estimate of the size of the Eurasian landmass, and his belief that Japan and other inhabited islands lay far to the east of the coast of China. In all three of these issues Columbus was both wrong and at odds with the scholarly consensus of his day.

As far back as the 3rd century BC, Eratosthenes had correctly computed the circumference of the Earth by using simple geometry and studying the shadows cast by objects at two different locations: Alexandria and Syene (modern-day Aswan).[22] Eratosthenes's results were confirmed by a comparison of stellar observations at Alexandria and Rhodes, carried out by Posidonius in the 1st century BC. These measurements were widely known among scholars, but confusion about the old-fashioned units of distance in which they were expressed had led, in Columbus's day, to some debate about the exact size of the Earth.

From d'Ailly's Imago Mundi Columbus learned of Alfraganus's estimate that a degree of latitude (or a degree of longitude along the Equator) spanned 56 ⅔ miles, but did not realize that this was expressed in the Arabic mile (about 1,830 m) rather than the shorter Roman mile with which he was familiar (1,480 m).[23] He therefore estimated the circumference of the Earth to be about 30,200 km, whereas the correct value is 40,000 km (25,000 mi).

Furthermore, most scholars accepted Ptolemy's estimate that Eurasia spanned 180° longitude, rather than the actual 130° (to the Chinese mainland) or 150° (to Japan at the latitude of Spain). Columbus, for his part, believed the even higher estimate of Marinus of Tyre, which put the longitudinal span of the Eurasian landmass at 225°, leaving only 135° of water. He also believed that Japan (which he called "Cipangu", following Marco Polo) was much larger, further to the east from China ("Cathay"), and closer to the Equator than it is, and that there were inhabited islands even further to the east than Japan, including the mythical Antillia, which he thought might lie not much further to the west than the Azores. In this he was influenced by the ideas of Florentine physician Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, who corresponded with Columbus before his death in 1482 and who also defended the feasibility of a westward route to Asia.[24]

Columbus therefore estimated the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan to be about 3,000 Italian miles (3,700 km, or 2,300 statute miles), while the correct figure is 19,600 km (12,200 mi)[citation needed], or about 12,000 km along a great circle. No ship in the 15th century could carry enough food and fresh water for such a long voyage and the dangers involved in navigating through the uncharted ocean would have been formidable. Most European navigators reasonably concluded that a westward voyage from Europe to Asia was unfeasible. The Catholic Monarchs, however, having completed an expensive war in the Iberian Peninsula, were desperate for a competitive edge over other European countries in the quest for trade with the Indies. Columbus promised such an advantage.

Nautical considerations

Though Columbus was wrong about the number of degrees of longitude that separated Europe from the Far East and about the distance that each degree represented, he did possess valuable knowledge about the trade winds, which would prove to be the key to his successful navigation of the Atlantic Ocean. During his first voyage in 1492, the brisk trade winds from the east, commonly called "easterlies", propelled Columbus' fleet for five weeks, from the Canary Islands to The Bahamas. To return to Spain against this prevailing wind would have required several months of an arduous sailing technique, called beating, during which food and drinkable water would probably have been exhausted.

Instead, Columbus returned home by following the curving trade winds northeastward to the middle latitudes of the North Atlantic, where he was able to catch the "westerlies" that blow eastward to the coast of Western Europe. There, in turn, the winds curve southward towards the Iberian Peninsula.[25][26][27]

It is unclear whether Columbus learned about the winds from his own sailing experience or if he had heard about them from others. The corresponding technique for efficient travel in the Atlantic appears to have been discovered first by the Portuguese, who referred to it as the Volta do mar ("turn of the sea"). Columbus' knowledge of the Atlantic wind patterns was, however, imperfect at the time of his first voyage. By sailing directly due west from the Canary Islands during hurricane season, skirting the so-called horse latitudes of the mid-Atlantic, Columbus risked either being becalmed or running into a tropical cyclone, both of which he luckily avoided.[24]

Funding campaign

In 1485, Columbus presented his plans to John II, King of Portugal. He proposed the king equip three sturdy ships and grant Columbus one year's time to sail out into the Atlantic, search for a western route to the Orient, and return.

Columbus also requested he be made "Great Admiral of the Ocean", appointed governor of any and all lands he discovered, and given one-tenth of all revenue from those lands.

The king submitted Columbus' proposal to his experts, who rejected it. It was their considered opinion that Columbus' estimation of a travel distance of 2,400 miles (3,860 km) was, in fact, far too short.[24]

In 1488 Columbus appealed to the court of Portugal once again, and once again John II invited him to an audience. It also proved unsuccessful, in part because not long afterwards Bartolomeu Dias returned to Portugal following a successful rounding of the southern tip of Africa. Now that it looked like Portugal could soon have the eastern sea route to Asia under its control, King John was no longer interested in Columbus' project.

Columbus traveled from Portugal to both Genoa and Venice, but he received encouragement from neither. Previously he had his brother sound out Henry VII of England, to see if the English monarch might not be more amenable to Columbus's proposal. After much carefully considered hesitation, Henry's invitation came too late. Columbus had already committed himself to Spain.[citation needed]

He had sought an audience from the monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, who had united many kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula by marrying, and were ruling together. On 1 May 1486, permission having been granted, Columbus presented his plans to Queen Isabella, who, in turn, referred it to a committee. After the passing of much time, the savants of Spain, like their counterparts in Portugal, reported back that Columbus had judged the distance to Asia much too short. They pronounced the idea impractical, and advised their Royal Highnesses to pass on the proposed venture.

However, to keep Columbus from taking his ideas elsewhere, and perhaps to keep their options open, the Catholic Monarchs gave him an annual allowance of 12,000 maravedis and in 1489 furnished him with a letter ordering all cities and towns under their domain to provide him food and lodging at no cost.[29]

U.S. stamps reflecting the most commonly held view as to what Columbus' first fleet might have looked like. The Santa Maria, the flagship of Columbus' fleet, was a carrack—a merchant ship of between 400 and 600 tons, 75 feet (23 m) long, with a beam of 25 feet (7.6 m), allowing it to carry more people and cargo. It had a deep draft of 6 feet (1.8 m). The vessel had three masts: a mainmast, a foremast, and a mizzenmast. Five sails altogether were attached to these masts. Each mast carried one large sail. The foresail and mainsail were square; the sail on the mizzen was a triangular sail known as a lateen mizzen. The ship had a smaller topsail on the mainmast above the mainsail and on the foremast above the foresail. In addition, the ship carried a small square sail, a spritsail, on the bowsprit.[30][31]

After continually lobbying at the Spanish court and two years of negotiations, he finally had success in 1492. Ferdinand and Isabella had just conquered Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula, and they received Columbus in Córdoba, in the Alcázar castle. Isabella turned Columbus down on the advice of her confessor, and he was leaving town by mule in despair, when Ferdinand intervened. Isabella then sent a royal guard to fetch him and Ferdinand later claimed credit for being "the principal cause why those islands were discovered".[32]

About half of the financing was to come from private Italian investors, whom Columbus had already lined up. Financially broke after the Granada campaign, the monarchs left it to the royal treasurer to shift funds among various royal accounts on behalf of the enterprise. Columbus was to be made "Admiral of the Seas" and would receive a portion of all profits. The terms were unusually generous, but as his son later wrote,[citation needed] the monarchs did not really expect him to return.

According to the contract that Columbus made with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, if Columbus discovered any new islands or mainland, he would receive many high rewards. In terms of power, he would be given the rank of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and appointed Viceroy and Governor of all the new lands. He had the right to nominate three persons, from whom the sovereigns would choose one, for any office in the new lands. He would be entitled to 10% of all the revenues from the new lands in perpetuity; this part was denied to him in the contract, although it was one of his demands. Additionally, he would also have the option of buying one-eighth interest in any commercial venture with the new lands and receive one-eighth of the profits.[24]

Columbus was later arrested in 1500 and supplanted from these posts. After his death, his sons Diego and Fernando took legal action to enforce their father's contract. Many of the smears against Columbus were initiated by the Castilian crown during these lengthy court cases, known as the pleitos colombinos. The family had some success in their first litigation, as a judgment of 1511 confirmed Diego's position as Viceroy, but reduced his powers. Diego resumed litigation in 1512, which lasted until 1536, and further disputes continued until 1790.[33]

Voyages

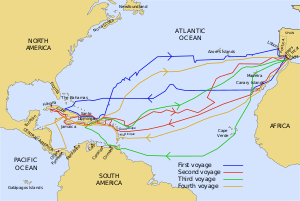

Between 1492 and 1503, Columbus completed four round-trip voyages between Spain and the Americas, all of them under the sponsorship of the Crown of Castile. These voyages marked the beginning of the European exploration and colonization of the American continents, and are thus of enormous significance in Western history. Columbus himself always insisted, in the face of mounting evidence to the contrary, that the lands that he visited during those voyages were part of the Asian continent, as previously described by Marco Polo and other European travelers.[10] Columbus' refusal to accept that the lands he had visited and claimed for Spain were not part of Asia might explain, in part, why the American continent was named after the Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci and not after Columbus.[34]

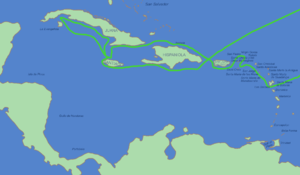

First voyage

On the evening of 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera with three ships; one larger carrack, Santa María, nicknamed Gallega (the Galician), and two smaller caravels, Pinta (the Painted) and Santa Clara, nicknamed Niña after her owner Juan Niño of Moguer.[35] They were property of Juan de la Cosa and the Pinzón brothers (Martín Alonso and Vicente Yáñez), but the monarchs forced the Palos inhabitants to contribute to the expedition. Columbus first sailed to the Canary Islands, which were owned by Castile, where he restocked the provisions and made repairs. On 6 September he departed San Sebastián de La Gomera for what turned out to be a five-week voyage across the ocean.

A lookout on the Pinta, Rodrigo de Triana (also known as Juan Rodriguez Bermeo), spotted land about 2 a.m. on the morning of October 12, and immediately alerted the rest of the crew with a shout. Thereupon, the captain of the Pinta, Juan Alonso Pinzón, verified the discovery and alerted Columbus by firing a lombard.[36] Columbus later maintained that he himself had already seen a light on the land a few hours earlier, thereby claiming for himself the lifetime pension promised by Ferdinand and Isabella to the first person to sight land.[37]

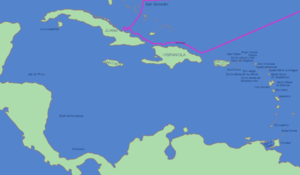

Columbus called the island (in what is now The Bahamas) San Salvador; the natives called it Guanahani. Exactly which island in the Bahamas this corresponds to is an unresolved topic; prime candidates are Samana Cay, Plana Cays, or San Salvador Island (so named in 1925 in the belief that it was Columbus's San Salvador). The indigenous people he encountered, the Lucayan, Taíno or Arawak, were peaceful and friendly. From the 12 October 1492 entry in his journal he wrote of them, "Many of the men I have seen have scars on their bodies, and when I made signs to them to find out how this happened, they indicated that people from other nearby islands come to San Salvador to capture them; they defend themselves the best they can. I believe that people from the mainland come here to take them as slaves. They ought to make good and skilled servants, for they repeat very quickly whatever we say to them. I think they can very easily be made Christians, for they seem to have no religion. If it pleases our Lord, I will take six of them to Your Highnesses when I depart, in order that they may learn our language."[38] He remarked that their lack of modern weaponry and even metal-forged swords or pikes was a tactical vulnerability, writing, "I could conquer the whole of them with 50 men, and govern them as I pleased."[39]

Columbus also explored the northeast coast of Cuba (landed on 28 October) and the northern coast of Hispaniola, by 5 December. Here, the Santa Maria ran aground on Christmas morning 1492 and had to be abandoned. He was received by the native cacique Guacanagari, who gave him permission to leave some of his men behind. Columbus left 39 men and founded the settlement of La Navidad at the site of present-day Môle-Saint-Nicolas, Haiti.[40] On 13 January 1493 Columbus made his last stop in the New World. He landed on the Samaná Peninsula where he met the hostile Ciguayos who presented him with his only violent resistance during his first voyage to the Americas. Because of this, and the Ciguayos' use of arrows, he called the inlet where he met them the Bay of Arrows (or Gulf of Arrows).[41] Today the place is called the Bay of Rincon, in Samaná, the Dominican Republic.[42] Columbus kidnapped about 10 to 25 natives and took them back with him (only seven or eight of the native Indians arrived in Spain alive, but they made quite an impression on Seville).[43]

Columbus headed for Spain, but another storm forced him into Lisbon. He anchored next to the King's harbor patrol ship on 4 March 1493 in Portugal. After spending more than one week in Portugal, he set sail for Spain. He crossed the bar of Saltes and entered the harbor of Palos on 15 March 1493. Word of his finding new lands rapidly spread throughout Europe.

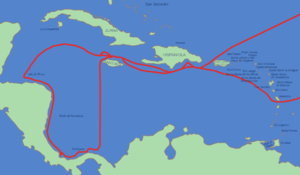

Second voyage

Columbus left Cadiz on 24 September 1493 to find new territories, with 17 ships carrying supplies, and about 1,200 men to colonize the region. The colonists included priests, farmers, and soldiers. This was part of a new policy — not just "colonies of exploitation", but "colonies of settlement" and conversion of the natives to Christianity.[44] The crew members may have included free black Africans who arrived in the New World about a decade before the slave trade began.[45] On 13 October the ships left the Canary Islands as they had on the first voyage, following a more southerly course.

On 3 November 1493, Columbus sighted a rugged island that he named Dominica (Latin for Sunday); later that day, he landed at Marie-Galante, which he named Santa Maria la Galante. After sailing past Les Saintes (Los Santos, The Saints), he arrived at Guadeloupe Santa María de Guadalupe de Extremadura, after the image of the Virgin Mary venerated at the Spanish monastery of Villuercas, in Guadalupe (Spain), which he explored between 4 November and 10 November 1493.

Michele da Cuneo, Columbus’s childhood friend from Savona, sailed with Columbus during the second voyage and wrote: "In my opinion, since Genoa was Genoa, there was never born a man so well equipped and expert in the art of navigation as the said lord Admiral."[46] Columbus named the small island of "Saona ... to honor Michele da Cuneo, his friend from Savona."[47] The father of Bartholomé de Las Casas also accompanied Colombus on this voyage.[48]

The exact course of his voyage through the Lesser Antilles is debated, but it seems likely that he turned north, sighting and naming several islands, including:

- Montserrat (for Santa Maria de Montserrate, after the Blessed Virgin of the Monastery of Montserrat, which is located on the Mountain of Montserrat, in Catalonia, Spain),

- Antigua (after a church in Seville, Spain, called Santa Maria la Antigua, meaning "Old St. Mary's"),

- Redonda (for Santa Maria la Redonda, Spanish for "round", owing to the island's shape),

- Nevis (derived from the Spanish, Nuestra Señora de las Nieves, meaning "Our Lady of the Snows", because Columbus thought the clouds over Nevis Peak made the island resemble a snow-capped mountain),

- Saint Kitts (for St. Christopher, patron of sailors and travelers),

- Saint Eustatius (for the early Roman martyr, St. Eustachius),

- Saba (also for St. Christopher?),

- Saint Martin (San Martin), and

- Saint Croix (from the Spanish Santa Cruz, meaning "Holy Cross"). He also sighted the island chain of the Virgin Islands (and named them Islas de Santa Ursula y las Once Mil Virgenes, Saint Ursula and the 11,000 Virgins, a cumbersome name that was usually shortened, both on maps of the time and in common parlance, to Islas Virgenes), and he also named the islands of Virgin Gorda (the fat virgin), Tortola, and Peter Island (San Pedro).

He continued to the Greater Antilles, and landed at Puerto Rico (originally San Juan Bautista, in honor of Saint John the Baptist, a name that was later supplanted by Puerto Rico (English: Rich Port) while the capital retained the name, San Juan) on 19 November 1493. One of the first skirmishes between native Americans and Europeans since the time of the Vikings[49] took place when Columbus's men rescued two boys who had just been castrated by their captors.

On 22 November Columbus returned to Hispaniola, where he intended to visit Fuerte de la Navidad (Christmas Fort), built during his first voyage, and located on the northern coast of Haiti. Columbus found Fuerte de la Navidad in ruins, destroyed by the native Taino people. Among the ruins were the corpses of 11 of the first 39 Spanish to have attempted New World colonization. Columbus then moved more than 100 kilometers eastwards, establishing a new settlement, which he called La Isabela, likewise on the northern coast of Hispaniola, in the present-day Dominican Republic.[50] However, La Isabela proved to be a poorly chosen location, and the settlement was short-lived.

He left Hispaniola on 24 April 1494, arrived at Cuba (naming it Juana) on 30 April. He explored the southern coast of Cuba, which he believed to be a peninsula rather than an island, and several nearby islands, including the Isle of Pines (Isla de las Pinas, later known as La Evangelista, The Evangelist). He reached Jamaica on 5 May. He retraced his route to Hispaniola, arriving on 20 August, before he finally returned to Spain.

Third voyage

On 30 May 1498, Columbus left with six ships from Sanlúcar, Spain, for his third trip to the New World.

Columbus led the fleet to the Portuguese island of Porto Santo, his wife's native land. He then sailed to Madeira and spent some time there with the Portuguese captain João Gonçalves da Camara before sailing to the Canary Islands and Cape Verde. Columbus landed on the south coast of the island of Trinidad on 31 July. From 4 August through 12 August he explored the Gulf of Paria which separates Trinidad from Venezuela. He explored the mainland of South America, including the Orinoco River. He also sailed to the islands of Chacachacare and Margarita Island and sighted and named Tobago (Bella Forma) and Grenada (Concepcion).

Columbus returned to Hispaniola on 19 August to find that many of the Spanish settlers of the new colony were discontented, having been misled by Columbus about the supposedly bountiful riches of the new world. An entry in his journal from September 1498 reads, "From here one might send, in the name of the Holy Trinity, as many slaves as could be sold..." Since Columbus supported the enslavement of the Hispaniola natives for economic reasons, he ultimately refused to baptize them, as Catholic law forbade the enslavement of Christians.[51]

He had some of his crew hanged for disobeying him. A number of returning settlers and sailors lobbied against Columbus at the Spanish court, accusing him and his brothers of gross mismanagement. On his return he was arrested for a period (see Governorship and arrest section below).

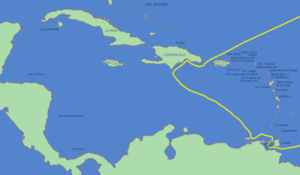

Fourth voyage

Before leaving for his fourth voyage, Columbus wrote a letter to the Governors of the Bank of St. George, Genoa, dated at Seville, 2 April 1502.[52] He wrote "Although my body is here my heart is always near you."[53]

Columbus made a fourth voyage nominally in search of the Strait of Malacca to the Indian Ocean. Accompanied by his brother Bartolomeo and his 13-year-old son Fernando, he left Cadiz, (modern Spain), on 11 May 1502, with the ships Capitana, Gallega, Vizcaína and Santiago de Palos. He sailed to Arzila on the Moroccan coast to rescue Portuguese soldiers whom he had heard were under siege by the Moors. On 15 June they landed at Carbet on the island of Martinique (Martinica). A hurricane was brewing, so he continued on, hoping to find shelter on Hispaniola. He arrived at Santo Domingo on 29 June but was denied port, and the new governor refused to listen to his storm prediction. Instead, while Columbus's ships sheltered at the mouth of the Rio Jaina, the first Spanish treasure fleet sailed into the hurricane. Columbus's ships survived with only minor damage, while 29 of the 30 ships in the governor's fleet were lost to the 1 July storm. In addition to the ships, 500 lives (including that of the governor, Francisco de Bobadilla) and an immense cargo of gold were surrendered to the sea.

After a brief stop at Jamaica, Columbus sailed to Central America, arriving at Guanaja (Isla de Pinos) in the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras on 30 July. Here Bartolomeo found native merchants and a large canoe, which was described as "long as a galley" and was filled with cargo. On 14 August he landed on the continental mainland at Puerto Castilla, near Trujillo, Honduras. He spent two months exploring the coasts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, before arriving in Almirante Bay, Panama on 16 October.

On 5 December 1502, Columbus and his crew found themselves in a storm unlike any they had ever experienced. In his journal Columbus writes,

For nine days I was as one lost, without hope of life. Eyes never beheld the sea so angry, so high, so covered with foam. The wind not only prevented our progress, but offered no opportunity to run behind any headland for shelter; hence we were forced to keep out in this bloody ocean, seething like a pot on a hot fire. Never did the sky look more terrible; for one whole day and night it blazed like a furnace, and the lightning broke with such violence that each time I wondered if it had carried off my spars and sails; the flashes came with such fury and frightfulness that we all thought that the ship would be blasted. All this time the water never ceased to fall from the sky; I do not say it rained, for it was like another deluge. The men were so worn out that they longed for death to end their dreadful suffering.[54]

In Panama, Columbus learned from the natives of gold and a strait to another ocean. After much exploration, in January 1503 he established a garrison at the mouth of the Rio Belen. On 6 April one of the ships became stranded in the river. At the same time, the garrison was attacked, and the other ships were damaged (Shipworms also damaged the ships in tropical waters.[55]). Columbus left for Hispaniola on 16 April heading north. On 10 May he sighted the Cayman Islands, naming them "Las Tortugas" after the numerous sea turtles there. His ships next sustained more damage in a storm off the coast of Cuba. Unable to travel farther, on 25 June 1503 they were beached in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica.

For a year Columbus and his men remained stranded on Jamaica. A Spaniard, Diego Mendez, and some natives paddled a canoe to get help from Hispaniola. That island's governor, Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres, detested Columbus and obstructed all efforts to rescue him and his men. In the meantime Columbus, in a desperate effort to induce the natives to continue provisioning him and his hungry men, successfully won the favor of the natives by correctly predicting a lunar eclipse for 29 February 1504, using the Ephemeris of the German astronomer Regiomontanus.[56] Help finally arrived, no thanks to the governor, on 29 June 1504, and Columbus and his men arrived in Sanlúcar, Spain, on 7 November.

Governorship and arrest

Under the terms of the Capitulations of Santa Fe, after his first voyage Columbus was appointed Viceroy and Governor of the Indies, which in practice entailed primarily the administration of the colonies in the island of Hispaniola, whose capital was established in Santo Domingo. By the end of his third voyage, Columbus was physically and mentally exhausted: his body was wracked by arthritis and his eyes by ophthalmia. In October 1499, he sent two ships to Spain, asking the Court of Spain to appoint a royal commissioner to help him govern. By then, accusations of tyranny and incompetence on the part of Columbus had also reached the Court.

The Court appointed Francisco de Bobadilla, a member of the Order of Calatrava, but not as the aide that Columbus had requested. Instead, Bobadilla was given complete control as governor from 1500 until his death in 1502. Arriving in Santo Domingo while Columbus was away, Bobadilla was immediately peppered with complaints about all three of Columbus's brothers: Christopher, Bartolomé, and Diego. Consuelo Varela, a Spanish historian, states: "Even those who loved him [Columbus] had to admit the atrocities that had taken place."[57][58]

As a result of these testimonies and without being allowed a word in his own defense, Columbus, upon his return, had manacles placed on his arms and chains on his feet and was cast into prison to await return to Spain. He was 48 years old.

On 1 October 1500, Columbus and his two brothers, likewise in chains, were sent back to Spain. Once in Cadiz, a grieving Columbus wrote to a friend at court:

It is now seventeen years since I came to serve these princes with the Enterprise of the Indies. They made me pass eight of them in discussion, and at the end rejected it as a thing of jest. Nevertheless I persisted therein... Over there I have placed under their sovereignty more land than there is in Africa and Europe, and more than 1,700 islands... In seven years I, by the divine will, made that conquest. At a time when I was entitled to expect rewards and retirement, I was incontinently arrested and sent home loaded with chains... The accusation was brought out of malice on the basis of charges made by civilians who had revolted and wished to take possession on the land.... I beg your graces, with the zeal of faithful Christians in whom their Highnesses have confidence, to read all my papers, and to consider how I, who came from so far to serve these princes... now at the end of my days have been despoiled of my honor and my property without cause, wherein is neither justice nor mercy.[60]

According to an uncatalogued document supposedly discovered very late in history purporting to be a record of Columbus's trial which contained the alleged testimony of 23 witnesses, Columbus regularly used barbaric acts of torture to govern Hispaniola.[51]

Columbus and his brothers lingered in jail for six weeks before busy King Ferdinand ordered their release. Not long after, the king and queen summoned the Columbus brothers to the Alhambra palace in Granada. There the royal couple heard the brothers' pleas; restored their freedom and wealth; and, after much persuasion, agreed to fund Columbus's fourth voyage. But the door was firmly shut on Columbus's role as governor. Henceforth Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres was to be the new governor of the West Indies.

Later life

While Columbus had always given the conversion of non-believers as one reason for his explorations, he grew increasingly religious in his later years. Probably with the assistance of his son Diego and his friend the Carthusian monk Gaspar Gorricio, Columbus produced two books during his later years: a Book of Privileges (1502), detailing and documenting the rewards from the Spanish Crown to which he believed he and his heirs were entitled, and a Book of Prophecies (1505), in which passages from the Bible were used to place his achievements as an explorer in the context of Christian eschatology.[10]

In his later years, Columbus demanded that the Spanish Crown give him 10% of all profits made in the new lands, as stipulated in the Capitulations of Santa Fe. Because he had been relieved of his duties as governor, the crown did not feel bound by that contract and his demands were rejected. After his death, his heirs sued the Crown for a part of the profits from trade with America, as well as other rewards. This led to a protracted series of legal disputes known as the pleitos colombinos ("Columbian lawsuits").

On 20 May 1506, at about age 55, Columbus died in Valladolid, fairly wealthy from the gold his men had accumulated in Hispaniola. At his death, he was still convinced that his journeys had been along the east coast of Asia. According to a study, published in February 2007, by Antonio Rodriguez Cuartero, Department of Internal Medicine of the University of Granada, he died of a heart attack caused by reactive arthritis. According to his personal diaries and notes by contemporaries, the symptoms of this illness (burning pain during urination, pain and swelling of the knees, and conjunctivitis) were clearly evident in his last three years.[63]

Columbus' remains were first interred at Valladolid, then at the monastery of La Cartuja in Seville (southern Spain) by the will of his son Diego, who had been governor of Hispaniola. In 1542 the remains were transferred to Colonial Santo Domingo, in the present-day Dominican Republic. In 1795, when France took over the entire island of Hispaniola, Columbus' remains were moved to Havana, Cuba. After Cuba became independent following the Spanish-American War in 1898, the remains were moved back to Spain, to the Cathedral of Seville,[64] where they were placed on an elaborate catafalque.

However, a lead box bearing an inscription identifying "Don Christopher Columbus" and containing bone fragments and a bullet was discovered at Santo Domingo in 1877.

To lay to rest claims that the wrong relics had been moved to Havana and that Columbus' remains had been left buried in the cathedral at Santo Domingo, DNA samples of the corpse resting in Seville were taken in June 2003 (History Today August 2003) as well as other DNA samples from the remaining of his sons Diego and Fernando Colón. Initial observations suggested that the bones did not appear to belong to somebody with the physique or age at death associated with Columbus.[65] DNA extraction proved difficult; only short fragments of mitochondrial DNA could be isolated. The mtDNA fragments matched corresponding DNA from Columbus' brother, giving support that both individuals had shared the same mother.[66][67] Such evidence, together with anthropologic and historic analyses led the researchers to conclude that the remains found in Seville belonged to Christopher Columbus.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). The authorities in Santo Domingo have never allowed the remains there to be exhumed, so it is unknown if any of those remains could be from Columbus' body as well.[67]Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). The location of the Dominican remains is in "The Colombus Lighthouse" (Faro a Colón), in Santo Domingo.

Commemoration

The World Columbian Exposition in Chicago, 1893, commemorated the 400th anniversary of the landing of Christopher Columbus in the Americas. Over 27 million people attended the exposition during its six-month duration.

The U.S. Postal Service participated in the celebration, issuing a series of 16 commemorative stamps depicting Columbus, Queen Isabella and others in the various stages of his several voyages. The issues range in value from the 1-cent to the 5-dollar denominations. Identical to the first Columbian Issue of 1893 a second Columbian issue was released in 1982, commemorating the 500th anniversary. These issues were made from the original dies of which the first engraved issues of 1893 were produced. In 1992 along with the United States, Spain also issued an almost identical series of Columbian issues, (using 'Spain' instead of 'United States of America') celebrating the 500th anniversary of the voyages.

The 400th anniversary Columbian issues were very popular in the United States; more than a billion of the two-cent editions were printed.[68]

Legacy

Although among non-Native Americans Christopher Columbus is traditionally considered the discoverer of America, Columbus was preceded by the various cultures and civilizations of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, as well as the Western world's Vikings at L'Anse aux Meadows. He is regarded more accurately as the person who brought the Americas into the forefront of Western attention. "Columbus's claim to fame isn't that he got there first," explains historian Martin Dugard, "it's that he stayed."[70] The popular idea that he was first person to envision a rounded earth is false. The rounded shape of the earth has already been known since antiquity.

Amerigo Vespucci's travel journals, published 1502-4, convinced Martin Waldseemüller that the discovered place was not India, as Columbus always believed, but a new continent, and in 1507, a year after Columbus's death, Waldseemüller published a world map calling the new continent America from Vespucci's Latinized name "Americus". According to Paul Lunde, "The preoccupation of European courts with the rise of the Ottoman Turks in the East partly explains their relative lack of interest in Columbus's discoveries in the West."[71]

Historically, the British had downplayed Columbus and emphasized the role of the Venetian John Cabot as a pioneer explorer, but for the emerging United States, Cabot made for a poor national hero. Veneration of Columbus in America dates back to colonial times. The name Columbia for "America" first appeared in a 1738 weekly publication of the debates of the British Parliament.[73] The use of Columbus as a founding figure of New World nations and the use of the word 'Columbia', or simply the name 'Columbus', spread rapidly after the American Revolution. In 1812, the name 'Columbus' was given to the newly founded capital of Ohio. During the last two decades of the 18th century the name "Columbia" was given to the federal capital District of Columbia, South Carolina's new capital city Columbia, the Columbia River, and numerous other places. Columbia is also the name of NASA's first Space shuttle and was the first to launch into orbit. Outside the United States the name was used in 1819 for the Gran Colombia, a precursor of the modern Republic of Colombia. The main plaza in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico is called Plaza Colón in honor of the Admiral.[74][75]

A candidate for sainthood in the Catholic Church in 1866, celebration of Columbus's legacy perhaps reached a zenith in 1892 when the 400th anniversary of his first arrival in the Americas occurred. Monuments to Columbus like the Columbian Exposition in Chicago were erected throughout the United States and Latin America extolling him. Numerous cities, towns, counties, and streets have been named after him, including the capital cities of two U.S. states: Ohio and South Carolina.

In 1909, descendants of Columbus undertook to dismantle the Columbus family chapel in Spain and move it to Boalsburg near State College, Pennsylvania, where it may now be visited by the public.[76] At the museum associated with the chapel, there are a number of Columbus relics worthy of note, including the armchair which the "Admiral of the Ocean Sea" used at his chart table.

More recent views of Columbus, particularly those of Native Americans, have tended to be much more critical.[77][78][79] This is because the native Taino of Hispaniola, where Columbus began a rudimentary tribute system for gold and cotton, disappeared so rapidly after contact with the Spanish, due to overwork and especially, after 1519, when the first pandemic struck Hispaniola,[80] due to European diseases.[81] Some estimates indicate case fatality rates of 80-90% in Native American populations during smallpox epidemics.[82] The native Taino people of the island were systematically enslaved via the encomienda system. The pre-Columbian population is estimated to have been perhaps 250,000-300,000. According to the historian Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdes by 1548, 56 years after Columbus landed, less than five hundred Taino were left on the island.[83] In another hundred years, perhaps only a handful remained. However, some analyses of the question of Columbus's legacy for Native Americans do not clearly distinguish between the actions of Columbus himself, who died well before the first pandemic to hit Hispaniola or the height of the encomienda system, and those of later European governors and colonists on Hispaniola.

The anniversary of Columbus's 1492 landing in the Americas is usually observed as Columbus Day on 12 October in Spain and throughout the Americas, except Canada. In the United States it is observed annually on the second Monday in October.

The term "pre-Columbian" is usually used to refer to the peoples and cultures of the Americas before the arrival of Columbus and his European successors.

Physical appearance

Although an abundance of artwork involving Christopher Columbus exists, no authentic contemporary portrait has been found.[84] James W. Loewen, author of Lies My Teacher Told Me, said that the various posthumous portraits have no historical value.[85]

Sometime between 1505 and 1536, Alejo Fernández painted an altarpiece, The Virgin of the Navigators, that includes a depiction of Columbus. The painting was commissioned for a chapel in Seville's Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) and remains there to this day, as the earliest known painting about the discovery of the Americas.[86][87]

At the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, 71 alleged portraits of Columbus were displayed, most did not match contemporary descriptions.[88] These writings describe him as having reddish or blond hair, which turned to white early in his life, light colored eyes,[89] as well as being a lighter skinned person with too much sun exposure turning his face red.

In keeping with descriptions of Columbus having had auburn hair or (later) white hair, textbooks have used the Sebastiano del Piombo painting (which in its normal-sized resolution shows Columbus's hair as auburn) so often that it has become the iconic image of Columbus accepted by popular culture. Accounts consistently describe Columbus as a large and physically strong man of some six feet or more in height, easily taller than the average European of his day.[90]

Popular culture

Columbus, an important historical figure, has been depicted in fiction, cinema and television, and in other media and entertainment, such as stage plays, music, cartoons and games.

- In games

- Christopher Columbus appears as a Great Explorer in the 2008 strategy video game, Civilization Revolution.[92]

- In literature

- In 1889, American author Mark Twain based the time traveler's trick in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court on Columbus' successful prediction of a lunar eclipse during his fourth voyage to the New World.

- In 1958, the Italian playwright Dario Fo wrote a satirical play about Columbus titled Isabella, tre caravelle e un cacciaballe (Isabella, three tall ships and a con man). In 1997 Fo was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The play was translated into English in 1988 by Ed Emery and is downloadable on the internet.[93]

- In 1991, author Salman Rushdie published a fictional representation of Columbus in The New Yorker, "Christopher Columbus and Queen Isabella of Spain Consummate Their Relationship, Santa Fe, January, 1492".[94]

- In Pastwatch: The Redemption of Christopher Columbus (1996) science fiction novelist Orson Scott Card focuses on Columbus' life and activities, but the novel's action also deals with a group of scientists from the future who travel back to the 15th century with the goal of changing the pattern of European contact with the Americas.

- British author Stephen Baxter includes Columbus' quest for royal sponsorship as a crucial historical event in his 2007 science fiction novel Navigator (ISBN 978-0-441-01559-7), the third entry in the author's Time's Tapestry Series.

- In music

- Christopher Columbus is regularly referred to by singers and musical groups in the Rastafari movement as an example of a European oppressor. The detractors include Burning Spear (Christopher Columbus), Culture (Capture Rasta), and Peter Tosh (You Can't Blame The Youth, Here Comes The Judge).

- Onscreen

- Christopher Columbus is a 1949 film starring Fredric March as Columbus.

- The 1985 TV mini-series, Christopher Columbus, features Gabriel Byrne as Columbus.

- Columbus was portrayed by Gérard Depardieu in the 1992 film by Ridley Scott, 1492: Conquest of Paradise. Scott presented Columbus as a forward-thinking idealist, as opposed to the view that he was ruthless and responsible for the misfortune of Native Americans.

- Carry On Columbus is a 1992 comedy.

- Christopher Columbus: The Discovery, is a 1992 biopic film by Alexander Salkind.

- The 42nd episode of The Sopranos, titled "Christopher" (2002), addresses the controversies surrounding Columbus' legacy from the perspectives of numerous identity group members.

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ Britannica "Christopher Columbus." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 8 June 2010

- ^ Scholastic Teacher - Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) Teaching Resources, Children's Book Recommendations, and Student Activities. Milton Meltzer. Author, Columbus and the World Around Him.

- ^ World Book - Columbus, Christopher "Columbus, Christopher". World Book Store has the encyclopedia, dictionary, atlas, homework help, study aids, and curriculum guides. 2010

- ^ Questia - COLUMBUS, CHRISTOPHER "Columbus, Christopher". Questia - The Online Library of Books and Journals. 2010

Memorials Of Columbus: Or, A Collection Of Authentic Documents Of That Celebrated Navigator (page 9) Country of origin: USA. Pages: 428. Publisher: BiblioBazaar. Publication Date: 2010-01-01.

Native American History for Dummies (page 127) Authors: Dorothy Lippert, Stephen J. Spignesi and Phil Konstantin. Paperback: 364 pages. Publisher: For Dummies. Publication Date: 2007-10-29.

The peoples of the Caribbean: an encyclopedia of archeology and traditional culture (page 67) Author: Nicholas J. Saunders. Hardcover: 399 pages. Publisher: ABC-CLIO. Publication Date: 2006-07-15. - ^ "Parks Canada — L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada". Pc.gc.ca. 2009-04-24. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ Hoxie, Frederic E. ed. Encyclopedia of North American Indians Houghton Mifflin (Mar 1997) ISBN 978-0-395-66921-1 p.568 [1][dead link]

- ^ Herbst, Philip The Color of Words: An Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Ethnic Bias in the United States Intercultural Press Inc (31 December 1997) ISBN 978-1-877864-97-1 p.116 [2]

- ^ Wilton, David; Brunetti, Ivan Word myths: debunking linguistic urban legends Oxford University Press USA (13 January 2005) ISBN 978-0-19-517284-3 pp.164-165 [3]

- ^ Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Page 9.

"Even with less than a complete record, however, scholars can state with assurance that Columbus was born in the republic of Genoa in northern Italy, although perhaps not in the city itself, and that his family made a living in the wool business as weavers and merchants...The two main early biographies of Columbus have been taken as literal truth by hundreds of writers, in large part because they were written by individual closely connected to Columbus or his writings. ...Both biographies have serious shortcomings as evidence." - ^ a b c d Encyclopedia Britannica, 1993 ed., Vol. 16, pp. 605ff / Morison, Christopher Columbus, 1955 ed., pp. 14ff

- ^ Telegraph, 14 Oct 2009, Georgetown University team led by Professor Estelle Irizarry claims that Christopher Columbus was Catalan

- ^ da Silva, Manuel Luciano and Silvia Jorge da Silva, 2008. Christopher Columbus was Portuguese. Express Printers, Fall River. ISBN 9781607028246.

- ^ "Georgetown University". Explore.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus". Thomas C. Tirado, Ph.D. Professor History. Millersville University.

- ^ "It is most probable that Columbus visited Bristol, where he was introduced to English commerce with Iceland." Bedini, Silvio A. and David Buisseret (1992). The Christopher Columbus encyclopedia, Volume 1, University of Michigan press, republished by Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-13-142670-2, p. 175

- ^ "Christopher Columbus (Italian explorer)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus Biography Page 2". Columbus-day.123holiday.net. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ Morgan, Edmund S. (2009). "Columbus' Confusion About the New World". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ "Marco Polo et le Livre des Merveilles", ISBN 978-2-35404-007-9 p.37

- ^ Boller, Paul F (1995). Not So!:Popular Myths about America from Columbus to Clinton. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195091861.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton 1991. Inventing the Flat Earth. Columbus and modern historians, Praeger, New York, Westport, London 1991;

Zinn, Howard 1980. A People's History of the United States, HarperCollins 2001. p.2 - ^ Sagan, Carl. Cosmos; the mean circumference of the Earth is 40,041.47 km.

- ^ Morison (1942, pp.65,93).

- ^ a b c d Samuel Eliot Morison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: The Life of Christopher Columbus, (Boston: Atlantic-Little, Brown, 1942). Reissued by the Morison Press, 2007. ISBN 1406750271 Cite error: The named reference "Morison-Admiral" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "The First Voyage Log". Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus and the Spanish Empire". Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ "Trade Winds and the Hadley Cell". Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ "Columbus Monuments Pages: Madrid". Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ Durant, Will The Story of Civilization vol. vi, "The Reformation". Chapter XIII, page 260.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus Ships". Elizabethan-era.org.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ^ "Columbus's Sailing Ships". Evgschool.org. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ^ Phillips, William D.; Phillips, Carla Rahn (1993). The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0521446525.

- ^ Mark McDonald, "Ferdinand Columbus, Renaissance Collector (1488-1539)", 2005, British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-7141-2644-9

- ^ "The Naming of America". Umc.sunysb.edu. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ^ The Original Nina The Columbus Foundation.

- ^ Morison (1942, p.226); Lopez, (1990, p.14); Columbus & Toscanelli (2010, p.35)

- ^ Lopez, (1990, p.15)

- ^ Robert H. Fuson, ed The Log of Christopher Columbus, Tab Books, 1992, International Marine Publishing, ISBN 0-87742-316-4.

- ^ "Columbus Day sparks debate over explorer's legacy".

- ^ Maclean, Frances (2008). "The Lost Fort of Columbus". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Oliver Dunn and James Kelly, The Diario of Christopher Columbus’s First Voyage to America (London: University of Oklahoma Press), 333-343.

- ^ Robert Fuson, The Log of Christopher Columbus (Camden, International Marine, 1987) 173.

- ^ James W. Loewen. Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. ASIN 1402579373.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Baccus, M. Kazim Utilization, Misuse, and Development of Human Resources in the Early West Ind Colonies Wilfrid Laurier University Press (2 January 2000) ISBN 978-0-88920-982-4 pp.6-7

- ^ "Who Went With Columbus? Dental Studies Give Clues.". The Washington Post. May 18, 2009.

- ^ Felipe Fernández-Armesto, Columbus, Oxford Univ. Press, (1991) pp. 103-104

- ^ Paolo Emilio Taviani, Columbus the Great Adventure, Orion Books, New York (1991) p. 185

- ^ Traboulay, David M. (1994). Columbus and Las Casas. University Press of America. p. 48. ISBN 0-8191-9642-8.

- ^ Phillips, Jr., William D. & Carla Rahn Phillips (1992). The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521350976.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Teeth Of Columbus' Crew Flesh Out Tale Of New World Discovery". ScienceDaily. March 20, 2009.

- ^ a b Who really sailed the ocean blue in 1492?, Christian Science Monitor, 17 October 2006

- ^ 'Letter from Christopher Columbus to the Governors of the Bank of St. George, Genoa. Dated at Seville, April 2nd, 1502'. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ^ The authentic letters of Columbus - Google Books. Books.google.com. 1894. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot,Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, Boston, 1942, page 617.

- ^ The History Channel. Columbus: The Lost Voyage.

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, 1942, pp. 653–54. Samuel Eliot Morison, Christopher Columbus, Mariner, 1955, pp. 184-92.

- ^ Giles Tremlett (2006-08-07). "Lost document reveals Columbus as tyrant of the Caribbean". The Guardian. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- ^ Bobadilla's 48-page report—derived from the testimonies of 23 people who had seen or heard about the treatment meted out by Columbus and his brothers—had originally been lost for centuries, but was rediscovered in 2005 in the Spanish archives in Valladolid. It contained an account of Columbus's seven-year reign as the first Governor of the Indies.

- ^ The Brooklyn Museum catalogue notes that the most likely source for Leutze's trio of Columbus paintings is Washington Irving’s best-selling Life and Voyages of Columbus (1828).

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, p. 576.

- ^ "Columbus Monuments Pages: Valladolid". Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ "Columbus Monuments Pages: Sevilla". Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ "Cause of the death of Columbus (in Spanish)". Eluniversal.com.mx. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "''Cristóbal Colón: traslación de sus restos mortales a la ciudad de Sevilla'' at Fundación Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes". Cervantesvirtual.com. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ Giles Tremlett, Young bones lay Columbus myth to rest, The Guardian, August 11, 2004

- ^ Lorenzi, Rossella (October 6, 2004). "DNA Suggests Columbus Remains in Spain". Discovery News. Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ^ a b DNA verifies Columbus’ remains in Spain, Associated Press, May 19, 2006

- ^ Scott's United States Stamp Catalogue, Commemorative index, quantities issued.

- ^ "Columbus Monuments Pages: Santo Domingo". Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ Dugard, Martin. The Last Voyage of Columbus. Little, Brown and Company: New York, 2005.

- ^ "Piri Reis and the Columbus Map". Paul Lunde. Saudi Aramco World. May/June 1992.

- ^ "Columbus Monuments Pages: Denver". Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ The Gentleman's Magazine, Vol. 8, June 1738, p. 285.

- ^ "Plaza Colón" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2009-07-27.[dead link]

- ^ Rigau, Jorge (2009). Puerto Rico Then and Now. San Diego, California: Thunder Bay Press. pp. 74–75.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Columbus Monuments Pages: Boalsburg". Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ Howard Zinn. "Christopher Columbus and the Indians". Newhumanist.com. Archived from the original on 2008-07-29. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "Jack Weatherford, Examining the reputation of Christopher Columbus". Hartford-hwp.com. 2001-04-20. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "Pre-Columbian Hispaniola — Arawak/Taino Indians". Hartford-hwp.com. 2001-09-15. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ Alfred W. Crosby, The Columbian Exchange, Westport, 1972, pp. 39, 47.

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A pest in the land: new world epidemics in a global perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 62. ISBN 0826328717.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ "The Cambridge encyclopedia of human paleopathology". Arthur C. Aufderheide, Conrado Rodríguez-Martín, Odin Langsjoen (1998). Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 0-521-55203-6.

- ^ Alfred Crosby, The Columbian Exchange (Westport, 1972) p. 45.

- ^ Alden, Henry Mills. Harper's New Monthly Magazine. Volume 84, Issues 499-504. Published by Harper & Brothers, 1892. Originally from Harvard University. Digitized on December 16, 2008. 732. Retrieved on September 8, 2009. 'Major, Int. Letters of Columbus, ixxxviii., says "Not one of the so-called portraits of Columbus is unquestionably authentic." They differ from each other, and cannot represent the same person.'

- ^ Loewen, James W. Lies My Teacher Told Me. 1st Touchstone ed, Simon & Schuster, 1996. ISBN 0-684-81886-8. 55.

- ^ John Noble, Susan Forsyth, Vesna Maric, Paula Hardy. Andalucía. Lonely Planet, 2007, p. 100

- ^ Linda Biesele Hall, Teresa Eckmann. Mary, mother and warrior, University of Texas Press, 2004, p. 46

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, pg. 47-48, Boston 1942.

- ^ Bartolomé de Las Casas, Historia de las Indias, ed. Agustín Millares Carlo, 3 vols. (Mexico City, 1951), book 1, chapter 2, 1:29. The Spanish word garzos is now usually translated as "light blue," but it seems to have connoted light grey-green or hazel eyes to Columbus's contemporaries. The word rubio can mean "blonde," "fair," or "ruddy." The Worlds of Christopher Columbus by William D. & Carla Rahn Phillips, pg. 282.

- ^ "DNA Tests on the bones of Christopher Columbus's bones, on his relatives and on Genoese and Catalin claimaints". Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ "Columbus Monuments Pages: Sacramento". Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ Civilization Revolution: Great People "CivFanatics" Retrieved on 4th September 2009

- ^ "Dario Fo Archives online". Archived from the original on 2009-10-21. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ The New Yorker, 17 June 1991, p. 32.

Bibliography

- Cohen, J.M. (1969) The Four Voyages of Christopher Columbus: Being His Own Log-Book, Letters and Dispatches with Connecting Narrative Drawn from the Life of the Admiral by His Son Hernando Colon and Others. London UK: Penguin Classics.

- Columbus, Christopher; Toscanelli, Paolo (2010) [1893]. Markham, Clements R. (ed.). The Journal of Christopher Columbus (During His First Voyage). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-01284-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cook, Sherburn and Woodrow Borah (1971) Essays in Population History, Volume I. Berkeley CA: University of California Press

- Crosby, A. W. (1987) The Columbian Voyages: the Columbian Exchange, and their Historians. Washington, DC: American Historical Association.

- Davidson, Miles H. (1997) Columbus Then and Now: A Life Reexamined, Norman and London, University of Oklahoma Press.

- Fuson, Robert H. (1992) The Log of Christopher Columbus. International Marine Publishing

- Keen, Benjamin (1978) The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by his Son Ferdinand, Westport CT: Greenwood Press.

- Loewen, James. Lies My Teacher Told Me

- Lopez, Barry (1990), The Rediscovery of North America, Lexicon, KY: University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 0-8131-1742-9

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morison, Samuel Eliot (1942), Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, Boston: Little, Brown and Company

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morison, Samuel Eliot, Christopher Columbus, Mariner, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1955

- Phillips, W. D. and C. R. Phillips (1992) The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Sale, Kirkpatrick The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy Plume, 1991

- Turner, Jack (2004) Spice: The History of a Temptation. New York: Random House.

- Wilford, John Noble (1991) The Mysterious History of Columbus: An Exploration of the Man, the Myth, the Legacy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

External links

![]() Quotations related to Christopher Columbus at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Christopher Columbus at Wikiquote

- Template:Worldcat id

- The Letter of Columbus to Luis de Sant Angel Announcing His Discovery

- Columbus Navigation

- Columbus Monuments Pages (overview of monuments for Columbus all over the world

Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- 1451 births

- 1506 deaths

- 15th-century explorers

- 15th-century Roman Catholics

- Age of Discovery

- Christopher Columbus

- Colonial governors of Santo Domingo

- Columbus family

- Explorers of Central America

- Italian expatriates in Spain

- Italian explorers

- Italian Roman Catholics

- People from Genoa (city)

- Spanish people of Italian descent

- Spanish Roman Catholics