Tattoo

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

A tattoo is body art made by inserting indelible ink into the dermis layer of the skin to change the pigment. Tattoos on humans are a type of decorative body modification, while tattoos on animals are most commonly used for identification purposes. The first written reference to the word, "tattoo" (or Samoan "Tatau") appears in the journal of Joseph Banks, the naturalist aboard Captain Cook's ship the HMS Endeavour in 1769: "I shall now mention the way they mark themselves indelibly, each of them is so marked by their humor or disposition".

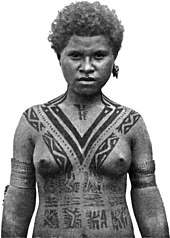

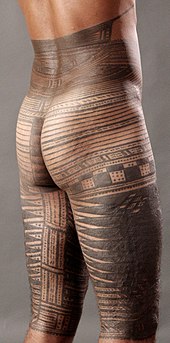

Tattooing has been practiced for centuries worldwide. The Ainu, the indigenous people of Japan, traditionally had facial tattoos. Today one can find Berbers of Tamazgha (North Africa), Māori of New Zealand, Hausa people of Northern Nigeria, Arabic people in East-Turkey and Atayal of Taiwan with facial tattoos. Tattooing was widespread among Polynesian peoples and among certain tribal groups in the Taiwan, Philippines, Borneo, Mentawai Islands, Africa, North America, South America, Mesoamerica, Europe, Japan, Cambodia, New Zealand and Micronesia. Despite some taboos surrounding tattooing, the art continues to be popular in many parts of the world.

Etymology

The Oxford English Dictionary gives the etymology of tattoo as "In 18th c. tattaow, tattow. From Polynesian tatau. In Tahitian, tatu." The word tatau was introduced as a loan word into English, the pronunciation being changed to conform to English phonology as "tattoo".[1] Sailors on later voyages both introduced the word and reintroduced the concept of tattooing to Europe.[2]

Tattoo enthusiasts may refer to tattoos as "Ink", "Tats", "Art", "Pieces", or "Work"; and to the tattooists as "Artists". The latter usage is gaining greater support, with mainstream art galleries holding exhibitions of both conventional and custom tattoo designs. Beyond Skin, at the Museum of Croydon, is an example of this as it challenges the stereotypical view of tattoos and who has them. Copyrighted tattoo designs that are mass-produced and sent to tattoo artists are known as flash, a notable instance of industrial design. Flash sheets are prominently displayed in many tattoo parlors for the purpose of providing both inspiration and ready-made tattoo images to customers.

The Japanese word irezumi means "insertion of ink" and can mean tattoos using tebori, the traditional Japanese hand method, a Western-style machine, or for that matter, any method of tattooing using insertion of ink. The most common word used for traditional Japanese tattoo designs is Horimono. Japanese may use the word "tattoo" to mean non-Japanese styles of tattooing.

In Taiwan, facial tattoos of the Atayal tribe are named "Badasun"; they are used to demonstrate that an adult man can protect his homeland, and that an adult woman is qualified to weave cloth and perform housekeeping.[citation needed]

The anthropologist Ling Roth in 1900 described four methods of skin marking and suggested they be differentiated under the names of tatu, moko, cicatrix, and keloid.[3]

History

Tattooing has been a Eurasian practice at least since around Neolithic times. Ötzi the Iceman, dating from the fourth to fifth millennium BC, was found in the Ötz valley in the Alps and had approximately 57 carbon tattoos consisting of simple dots and lines on his lower spine, behind his left knee, and on his right ankle. These tattoos were thought to be a form of healing because of their placement which resembles acupuncture.[19] Other mummies bearing tattoos and dating from the end of the second millennium BC have been discovered, such as the Mummy of Amunet from ancient Egypt and the mummies at Pazyryk on the Ukok Plateau.[4]

Pre-Christian Germanic, Celtic and other central and northern European tribes were often heavily tattooed, according to surviving accounts. The Picts were famously tattooed (or scarified) with elaborate dark blue woad (or possibly copper for the blue tone) designs. Julius Caesar described these tattoos in Book V of his Gallic Wars (54 BC).

Tattooing in Japan is thought to go back to the Paleolithic era, some ten thousand years ago.[citation needed] Various other cultures have had their own tattoo traditions, ranging from rubbing cuts and other wounds with ashes, to hand-pricking the skin to insert dyes.

Tattooing in the Western world today has its origins in Polynesia, and in the discovery of tatau by eighteenth century explorers. The Polynesian practice became popular among European sailors, before spreading to Western societies generally.[5]

Types of tattoos

The American Academy of Dermatology distinguishes 5 types of tattoos:[6] traumatic tattoos, also called "natural tattoos", that result from injuries, especially asphalt from road injuries or pencil lead; amateur tattoos; professional tattoos, both via traditional methods and modern tattoo machines; cosmetic tattoos, also known as "permanent makeup"; and medical tattoos.

Traumatic tattoos

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

According to George Orwell, coal miners could develop characteristic tattoos owing to coal dust getting into wounds.[7] This can also occur with substances like gunpowder. Similarly, a traumatic tattoo occurs when a substance such as asphalt is rubbed into a wound as the result of some kind of accident or trauma. These are particularly difficult to remove as they tend to be spread across several different layers of skin, and scarring or permanent discoloration is almost unavoidable depending on the location.

In addition, tattooing of the gingiva from implantation of amalgam particles during dental filling placement and removal is possible and not uncommon. A common example of such accidental tattoos is the result of a deliberate or accidental stabbing with a pencil or pen, leaving graphite or ink beneath the skin.

Amateur and professional tattoos

Many tattoos serve as rites of passage, marks of status and rank, symbols of religious and spiritual devotion, decorations for bravery, sexual lures and marks of fertility, pledges of love, punishment, amulets and talismans, protection, and as the marks of outcasts, slaves and convicts. The symbolism and impact of tattoos varies in different places and cultures. Tattoos may show how a person feels about a relative (commonly mother/father or daughter/son) or about an unrelated person.

Today, people choose to be tattooed for cosmetic, sentimental/memorial, religious, and magical reasons, and to symbolize their belonging to or identification with particular groups, including criminal gangs (see criminal tattoos) but also a particular ethnic group or law-abiding subculture. Some Māori still choose to wear intricate moko on their faces. In Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand, the yantra tattoo is used for protection against evil and to increase luck.

In the Philippines certain tribal groups believe that tattoos have magical qualities, and help to protect their bearers. Most traditional tattooing in the Philippines is related to the bearer's accomplishments in life or rank in the tribe. Among Catholic Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina, tattoos with Christian symbols would be inked on to protect themselves from the Muslim Turks.

Extensive decorative tattooing is common among members of traditional freak shows and by performance artists who follow in their tradition.

Identification

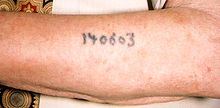

People have also been forcibly tattooed. A well-known example is the identification system for inmates in Nazi concentration camps during the Holocaust. Tattoos have also been used for identification in other ways.

For example, during the Roman Empire, Roman soldiers were required by law to have indentifying tattoos on their hands in order to make it difficult to hide if they deserted. Gladiators and slaves were likewise tattooed, exported slaves were tattooed with the words "tax paid" and it was a common practice to tattoo "Stop me, I'm a runaway" on their foreheads. Emperor Constantine I banned tattooing the face around AD 330 and the Second Council of Nicaea banned all body markings as a pagan practice in AD 787.[8] The Latin word for "tattoo" was "stigma", hence the English word "stigmatise".

In the period of early contact between the Māori and Europeans, Māori chiefs sometimes drew their moko (facial tattoo) on documents in place of a signature. Tattoos are sometimes used by forensic pathologists to help them identify burned, putrefied, or mutilated bodies. Tattoo pigment is buried deep enough in the skin that even severe burns are not likely to destroy a tattoo.[citation needed]

For many centuries seafarers have undergone tattooing for the purpose of enabling identification after drowning. In this way recovered bodies of such drowned persons could be connected with their family members or friends before burial. Therefore tattooists often worked in ports where potential customers were numerous. This traditional custom lives on in the modern era.[citation needed]

Tattoos are also placed on animals, though very rarely for decorative reasons. Pets, show animals, thoroughbred horses and livestock are sometimes tattooed with identification and other marks. Pet dogs and cats are often tattooed with a serial number (usually in the ear, or on the inner thigh) via which their owners can be identified.

Also, animals are occasionally tattooed to prevent sunburn (on the nose, for example). Such tattoos are often performed by a veterinarian and in most cases the animals are anesthetized during the process. Branding is used for similar reasons and is often performed without anesthesia, but is different from tattooing as no ink or dye is inserted during the process.

Cosmetic

When used as a form of cosmetics, tattooing includes permanent makeup and hiding or neutralizing skin discolorations. Permanent makeup is the use of tattoos to enhance eyebrows, lips (liner and/or lipstick), eyes (liner), and even moles, usually with natural colors, as the designs are intended to resemble makeup.

Medical

Medical tattoos are used to ensure instruments are properly located for repeated application of radiotherapy and for the areola in some forms of breast reconstruction. Tattooing has also been used to convey medical information about the wearer (e.g. blood group, medical condition, etc). Tattoos are used in skin tones to cover vitiligo, skin pigmentation disorder.

Prevalence

Tattoos have experienced a resurgence in popularity in many parts of the world, particularly in North and South America, Japan, and Europe. The growth in tattoo culture has seen an influx of new artists into the industry, many of whom have technical and fine arts training. Coupled with advancements in tattoo pigments and the ongoing refinement of the equipment used for tattooing, this has led to an improvement in the quality of tattoos being produced.[9]

During the first decade of the 21st century, the presence of tattoos became evident within pop culture, inspiring television shows such as A&E's Inked and TLC's Miami Ink and LA Ink. The decoration of blues singer Janis Joplin with a wristlet and a small heart on her left breast, by the San Francisco tattoo artist Lyle Tuttle, has been called a seminal moment in the popular acceptance of tattoos as art.[10] Formal interest in the art of the tattoo became prominent in the 1990s through the beginning of the 21st century. Contemporary art exhibitions and visual art institutions have featured tattoos as art through such means as displaying tattoo flash, examining the works of tattoo artists, or otherwise incorporating examples of body art into mainstream exhibits. One such 2009 Chicago exhibition Freaks & Flash featured both examples of historic body art as well as the tattoo artists who produced it.[11]

In many traditional cultures tattooing has also enjoyed a resurgence, partially in deference to cultural heritage. Historically, a decline in traditional tribal tattooing in Europe occurred with the spread of Christianity[citation needed]. However, some Christian groups, such as the Knights of St. John of Malta, sported tattoos to show their allegiance. A decline often occurred in other cultures following European efforts to convert aboriginal and indigenous people to Western religious and cultural practices that held tattooing to be a "pagan" or "heathen" activity. Within some traditional indigenous cultures, tattooing takes place within the context of a rite of passage between adolescence and adulthood.

Tattooing has become a fad among celebrities. David Beckham, an international soccer star, caught tattoo ‘fever’ beginning with the birth of his first son back in 1999 when he had Malloy ink his son’s name, “Brooklyn” at the bottom of his back. Then he had the first part of his guardian angel inked on his back. This was followed up in 2000, with his wife’s name being misspelled in Hindi on his left arm.[12]

Many studies have been done of the tattooed population and society's view of tattoos. In June 2006 the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology published the results of a telephone survey which took place in 2004. It found that 36% of Americans ages 18–29, 24% of those 30-40 and 15% of those 41-51 had a tattoo.[13] In September 2006, the Pew Research Center conducted a telephone survey which found that 36% of Americans ages 18–25, 40% of those 26-40 and 10% of those 41-64 had a tattoo.[14] In January 2008, a survey conducted online by Harris Interactive estimated that 14% of all adults in the United States have a tattoo, just slightly down from 2003, when 16% had a tattoo. Among age groups, 9% of those ages 18–24, 32% of those 25-29, 25% of those 30-39 and 12% of those 40-49 have tattoos, as do 8% of those 50-64. Men are just slightly more likely to have a tattoo than women (15% versus 13%)[15]

Negative associations

In Japan, tattoos are strongly associated with organized crime organizations known as the yakuza, particularly full body tattoos done the traditional Japanese way (Tebori). Many public Japanese bathhouses (sentō) and gymnasiums often openly ban those bearing large or graphic tattoos in an attempt to prevent Yakuza from entering.[16] The Government of Meiji Japan had outlawed tattoos in the 19th century, a prohibition that stood for 70 years before being repealed in 1948.[17]

In the United States many prisoners and criminal gangs use distinctive tattoos to indicate facts about their criminal behavior, prison sentences, and organizational affiliation.[18] A tear tattoo, for example, can be symbolic of murder, with each tear representing the death of a friend. At the same time, members of the U.S. military have an equally well established and longstanding history of tattooing to indicate military units, battles, kills, etc., an association which remains widespread among older Americans. Tattooing is also common in the British Armed Forces.

Tattooing was also used by the Nazi regime in Nazi concentration camps to tag prisoners.

Insofar as this cultural or subcultural use of tattoos predates the widespread popularity of tattoos in the general population, tattoos are still associated with criminality. Tatoos on the face in the shape of teardrops are usually associated with how many people a person has murdered. Although the general acceptance of tattoos is on the rise in Western society, they still carry a heavy stigma among certain social groups. Tattoos are generally considered an important part of the culture of the Russian mafia.

The prevalence of women in the tattoo industry, along with larger numbers of women bearing tattoos, appears to be changing negative perceptions. A study of "at-risk" (as defined by school absenteeism and truancy) adolescent girls showed a positive correlation between body-modification and negative feelings towards the body and self-esteem; however, also illustrating a strong motive for body-modification as the search for "self and attempts to attain mastery and control over the body in an age of increasing alienation."[19]

Religious perspectives

Christianity

There is no consistent Christian position on tattooing. The early Christian Montanist movement practiced tattooing as putting signs or seals of God's name according to Rev. 7:3; 9:4; 13:16; 14:1; 20:4; 22:4.

The majority of Christians do not take issue with the practice, while a minority uphold the Hebrew view against tattoos (see below) based on Leviticus 19:28. Tattoos of Christian symbols are common. When on pilgrimage, some Christians get a small tattoo dating the year and a small cross. This is usually done on the forearm.

Catholic Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina used tattooing, especially of children, for perceived protection against forced conversion to Islam during Turkish occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1463-1878). This form of tattooing continued long past its original motivation, though it was forbidden during Yugoslavian communism. Tattooing was performed during spring time or during special religious celebrations such as the Feast of St. Joseph, and consisted mostly of Christian crosses on hands, fingers, forearms, and below the neck and on the chest.[20][21][22]

Coptic Christians who live in Egypt tattoo themselves with the symbols of Coptic crosses on their right wrists.

Mormonism

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (often referred to as "Latter-day Saints" or "Mormons") have been advised by their church leaders to not tattoo their bodies.[23] In the Articles of Faith of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints it states that the Latter-day Saints accept the Bible to be the word of God[24] Therefore, the church believes that the body is a sacred temple as preached in the New Testament,[25] and that they should keep it clean, inside and out. Tattooing, among other things, is discouraged.

Islam

Tattoos are considered forbidden in Sunni Islam. According to the book of Sunni traditions, Sahih Bukhari, "The Prophet forbade [...] mutilation (or maiming) of bodies."[26] Sunni Muslims believe tattooing is forbidden and a sin because it involves changing the creation of God (Surah 4 Verse 117-120), and because the Prophet cursed the one who does tattoos and the one for whom that is done.[27] There is, however, difference of scholarly Sunni Muslim opinion as to the reason why tattoos are forbidden.[28]

The use of temporary tattoos made with henna is very common and is considered permissible in Muslim Morocco and Tunisia and other predominantly Muslim nations such as Indonesia and Malaysia. The permissibility of tattoos is debated in Shi'a Islam, with some Shi'a pointing to a ruling by Ayatollah Sistani stating they are permitted.[29]

Judaism

Tattoos are forbidden in Judaism[30] based on the Torah (Leviticus 19:28): "You shall not make gashes in your flesh for the dead, or incise any marks on yourselves: I am the Lord." The prohibition is explained by contemporary rabbis as part of a general prohibition on body modification that does not serve a medical purpose (such as to correct a deformity). Maimonides, a leading 12th century scholar of Jewish law and thought, explains the prohibition against tattoos as a Jewish response to paganism.

Since it was common practice for ancient pagan worshipers to tattoo themselves with religious iconography and names of gods, Judaism prohibited tattoos entirely in order to disassociate from other religions. In modern times, the association of tattoos with Nazi concentration camps and the Holocaust has given an additional level for revulsion to the practice of tattooing, even among many otherwise fairly secular Jews. It is a common misconception that anyone bearing a tattoo is not permitted to be buried in a Jewish cemetery.

Neopagan

Neopagans can use the process and the outcome of tattooing as an expression or representation of their beliefs.[31] Many tattooists' websites offer pagan images as examples of the kinds of artwork they provide.

Procedure

Tattooing involves the placement of pigment into the skin's dermis, the layer of dermal tissue underlying the epidermis. After initial injection, pigment is dispersed throughout a homogenized damaged layer down through the epidermis and upper dermis, in both of which the presence of foreign material activates the immune system's phagocytes to engulf the pigment particles. As healing proceeds, the damaged epidermis flakes away (eliminating surface pigment) while deeper in the skin granulation tissue forms, which is later converted to connective tissue by collagen growth. This mends the upper dermis, where pigment remains trapped within fibroblasts, ultimately concentrating in a layer just below the dermis/epidermis boundary. Its presence there is stable, but in the long term (decades) the pigment tends to migrate deeper into the dermis, accounting for the degraded detail of old tattoos.[32]

Some tribal cultures traditionally created tattoos by cutting designs into the skin and rubbing the resulting wound with ink, ashes or other agents; some cultures continue this practice, which may be an adjunct to scarification. Some cultures create tattooed marks by hand-tapping the ink into the skin using sharpened sticks or animal bones (made like needles) with clay formed disks or, in modern times, needles. Traditional Japanese tattoos (Horimono) are still "hand-poked," that is, the ink is inserted beneath the skin using non-electrical, hand-made and hand held tools with needles of sharpened bamboo or steel. This method is known as tebori.

Traditional Hawaiian hand-tapped tattoos are experiencing a renaissance, after the practice was nearly extinguished in the years following Western contact. The process involves lengthy protocols and prayers and is considered a sacred rite more than an application of artwork. The tattooist chooses the design, rather than the wearer, based on genealogical information. Each design is symbolic of the wearer's personal responsibility and role in the community. Tools are hand-carved from bone or tusk without the use of metal.[33]

The most common method of tattooing in modern times is the electric tattoo machine, which inserts ink into the skin via a single needle or a group of needles that are soldered onto a bar, which is attached to an oscillating unit. The unit rapidly and repeatedly drives the needles in and out of the skin, usually 80 to 150 times a second. This modern procedure is ordinarily sanitary. The needles are single-use needles that come packaged individually. The tattoo artist must wash not only his or her hands, but he or she must also wash the area that will be tattooed. Gloves must be worn at all times and the wound must be wiped frequently with a wet disposable towel of some kind. The equipment must be sterilized in a certified autoclave before and after every use.

Prices for this service vary widely globally and locally, depending on the complexity of the tattoo, the skill and expertise of the artist, the attitude of the customer, the costs of running a business, the economics of supply and demand, etc. The time it takes to get a tattoo is in proportion with its size and complexity. A small one of simple design might take fifteen minutes, whereas an elaborate sleeve tattoo or back piece requires multiple sessions of several hours each.

The modern electric tattoo machine is far removed from the machine invented by Samuel O'Reilly in 1891. O'Reilly's machine was based on the rotary technology of the electric engraving device invented by Thomas Edison. Modern tattoo machines use electromagnetic coils. The first coil machine was patented by Thomas Riley in London, 1891 using a single coil. The first twin coil machine, the predecessor of the modern configuration, was invented by another Englishman, Alfred Charles South of London, in 1899.

Another tattoo machine was developed 1970-1978 by the German tattoo artists Horst Heinrich Streckenbach[34] (1929–2001) and Manfred Kohrs.[35]

Dyes and pigments

Early tattoo inks were obtained directly from nature and were extremely limited in pigment variety. In ancient Hawaii, for example, kukui nut ash was blended with coconut oil to produce an ebony ink.[33] Today, an almost unlimited number of colors and shades of tattoo ink are mass-produced and sold to parlors worldwide. Tattoo artists commonly mix these inks to create their own unique pigments.

A wide range of dyes and pigments can be used in tattoos, from inorganic materials like titanium dioxide and iron oxides to carbon black, azo dyes, and acridine, quinoline, phthalocyanine and naphthol derivates, dyes made from ash, and other mixtures. Iron oxide pigments are used in greater extent in cosmetic tattooing.

Modern tattooing inks are carbon based pigments that have uses outside of commercial tattoo applications. In 2005 at Northern Arizona University a study characterized the makeup of tattoo inks (Finley-Jones and Wagner). The FDA expects local authorities to legislate and test tattoo pigments and inks made for the use of permanent cosmetics. In California, the state prohibits certain ingredients and pursues companies who fail to notify the consumer of the contents of tattoo pigments.

There has been concern expressed about the interaction between magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) procedures and tattoo pigments, some of which contain trace metals. Allegedly, the magnetic fields produced by MRI machines could interact with these metal particles, potentially causing burns or distortions in the image. The television show MythBusters tested the hypothesis, and found a slight interaction between commonly used tattoo inks and MRI. The interaction was stronger with inks containing high levels of iron oxide.[36][37]

Professional tattooists rely primarily on the same pigment base found in cosmetics. Amateurs will often use drawing inks such as low grade India ink, but these inks often contain impurities and toxins which can lead to illness or infection.

Studio hygiene

The properly equipped tattoo studio will use biohazard containers for objects that have come into contact with blood or bodily fluids, sharps containers for old needles, and an autoclave for sterilizing tools.[38] Certain jurisdictions also require studios by law to have a sink in the work area supplied with both hot and cold water.

Proper hygiene requires a body modification artist to wash his or her hands before starting to prepare a client for the stencil, between clients, and at any other time where cross contamination can occur. The use of single use disposable gloves is also mandatory. Also, disposable gloves should be taken off after each stage of tattooing. The same gloves should not be used to clean the tattoo station, tattoo the client, or clean the tattoo; the tattoo artist should change their disposable gloves at each stage. In some states and countries it is illegal to tattoo a minor even with parental consent, and (except in the case of medical tattoos) it is forbidden to tattoo impaired persons, people with contraindicated skin conditions, those who are pregnant or nursing, those incapable of consent due to mental incapacity or those under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

Before the tattooing begins the client is asked to approve the final position of the applied stencil. After approval is given the artist will open new, sterile needle packages in front of the client, and always use new, sterile or sterile disposable instruments and supplies, and fresh ink for each session (loaded into disposable ink caps which are discarded after each client). Also, all areas which may be touched with contaminated gloves will be wrapped in clear plastic to prevent cross-contamination. Equipment that cannot be autoclaved (such as counter tops, machines, and furniture) will be wiped with an approved disinfectant.[39]

Membership in professional organizations, or certificates of appreciation/achievement, generally helps artists to be aware of the latest trends. However, many of the most notable tattooists do not belong to any association. While specific requirements to become a tattooist vary between jurisdictions, many mandate only formal training in bloodborne pathogens, and cross contamination. The local department of health regulates tattoo studios in many jurisdictions.

For example, according to the health departments in Oregon and Hawaii, tattoo artists in these states are required to take and pass a test ascertaining their knowledge of health and safety precautions, as well as the current state regulations. Performing a tattoo in Oregon state without a proper and current license or in an unlicensed facility is a felony offense.[40] Tattooing was legalized in New York City in 1997,[41] and in Massachusetts and Oklahoma between 2002 and 2006.

Aftercare

Tattoo artists, and people with tattoos, vary widely in their preferred methods of caring for new tattoos. Some artists recommend keeping a new tattoo wrapped for the first twenty-four hours, while others suggest removing temporary bandaging after two hours or less to allow the skin to 'breathe'. Many tattooists advise against allowing too much contact with hot tub or pool water, or soaking in a tub for the first two weeks. This is to prevent the tattoo ink from washing out or fading due to over-hydration and to avoid infection from exposure to bacteria. In contrast, other artists suggest that a new tattoo be bathed in very hot water early.

General consensus for care advises against removing the scab that may form on a new tattoo, and avoiding exposing one's tattoo to the sun for extended periods for at least 3 weeks; both of these can contribute to fading of the image. Furthermore, it is agreed that a new tattoo needs to be kept clean. Various products may be recommended for application to the skin, ranging from those intended for the treatment of cuts, burns and scrapes, to cocoa butter, hemp, salves, lanolin, A&D, Bepanthen or Aquaphor.[42] Oil based ointments are almost always recommended to be used in very thin layers due to their inability to evaporate and therefore over-hydrate the already perforated skin. In recent years, specific commercial products have been developed for tattoo aftercare. Although opinions about these products vary, there is near total agreement that either alone or in addition to some other product, soap and warm water work well to keep a tattoo clean and free from infection.[43] Ultimately, the amount of ink that remains in the skin throughout the healing process determines, in large part, how robust the final tattoo will look. If a tattoo becomes infected (uncommon but possible if one neglects to properly clean their tattoo) or if the scab falls off too soon (e.g. if it absorbs too much water and sloughs off early or is picked or scraped off), then the ink will not be properly fixed in the skin and the final image will be negatively affected.

Health risks

Because it requires breaking the skin barrier, tattooing may carry health risks, including infection and allergic reactions. Modern tattooists reduce such risks by following universal precautions, working with single-use items, and sterilizing their equipment after each use. Many jurisdictions require that tattooists have blood-borne pathogen training, such as is provided through the Red Cross and OSHA.

In amateur tattoos, such as those applied in prisons, however, there is an elevated risk of infection. Infections that can theoretically be transmitted by the use of unsterilized tattoo equipment or contaminated ink include surface infections of the skin, herpes simplex virus, tetanus, staph, fungal infections, some forms of hepatitis, tuberculosis, and HIV.[44] In the United States there have been no reported cases of HIV contracted via commercially-applied tattooing process.[45]

Tattoo inks have been described as "remarkably nonreactive histologically".[32] However, cases of allergic reactions to tattoo inks, particularly certain colors, have been medically documented.[citation needed] This is sometimes due to nickel in an ink pigment, which is a common metal allergy.[46][47] Occasionally, when a blood vessel is punctured during the tattooing procedure a bruise/hematoma may appear.

Tattoo removal

While tattoos are considered permanent, it is sometimes possible to remove them with laser treatments, fully or partially. Typically, black and some colored inks can be removed more completely. The expense and pain of removing tattoos will typically be greater than the expense and pain of applying them. Pre-laser tattoo removal methods include dermabrasion, salabrasion (scrubbing the skin with salt), cryosurgery, and excision which is sometimes still used along with skin grafts for larger tattoos.[48] These older methods however have been nearly completely replaced by laser removal treatment options.

Temporary tattoos

Temporary tattoos are popular with models and children as they involve no permanent alteration of the skin but produce a similar appearance that can last anywhere from a few days to several weeks. The most common style is a type of body sticker similar to a decal, which is typically transferred to the skin using water. Although the design is waterproof, it can be removed easily with oil-based creams. Originally inserted as a prize in bubble gum packages, they consisted of a poor quality ink transfer that would easily come off with water or rubbing. Today's vegetable dye temporaries can look extremely realistic and adhere up to 3 weeks due to a layer of glue similar to that found on an adhesive bandage.

Henna tattoos (Mehndi) and silver nitrate stains that appear when exposed to ultraviolet light can take up to two weeks to fade from the skin. Silver nitrate is, however, a toxic substance and should not be used on skin.[49] Temporary airbrush tattoos (TATs) are applied by covering the skin with a stencil and spraying the skin with ink. In the past, this form of tattoo only lasted about a week. With the newest inks, tattoos can reasonably last for up to two weeks. Airbrush tattoos are generally sprayed with cosmetic paints. The ease of removal is a factor in their growing popularity. Unlike henna tattoos, the cosmetic paints can be rubbed off with isopropyl alcohol.

See also

- Chinese character tattoos

- Criminal tattoo

- Five dots tattoo

- Foreign body reaction

- Legal status of tattooing in the United States

- List of tattoo artists

- Lucky Diamond Rich, world's most tattooed person.

- Lower back tattoo

- Marquesan tattoo

- Prison tattooing

- SS blood group tattoo

- Tattoo convention

- Tattooing of Minors Act 1969 (in the UK)

- Teardrop tattoo

- UV tattoo

References

Bibliography

- Anthropological

- Buckland, A. W. (1887) "On Tattooing," in Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1887/12, p. 318-328

- Caplan, Jane (ed.) (2000): Written on the Body: the Tattoo in European and American History, Princeton U P

- DeMello, Margo (2000) Bodies of Inscription: a Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community, California. Durham NC: Duke University Press

- Fisher, Jill A. (2002). Tattooing the Body, Marking Culture. Body & Society 8 (4): pp. 91–107.

- Gell, Alfred (1993) Wrapping in Images: Tattooing in Polynesia, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Gilbert, Stephen G. (2001) Tattoo History: a Source Book, New York: Juno Books

- Gustafson, Mark (1997) "Inscripta in fronte: Penal Tattooing in Late Antiquity," in Classical Antiquity, April 1997, Vol. 16/No. 1, p. 79-105

- Hambly, Wilfrid Dyson (1925) The History of Tattooing and Its Significance: With Some Account of Other Forms of Corporal Marking, London: H. F.& G. Witherby (reissued: Detroit 1974)

- Hesselt van Dinter, Maarten (2005) The World of Tattoo; An Illustrated History. Amsterdam, KIT Publishers

- Jones, C. P. (1987) "Stigma: Tattooing and Branding in Graeco-Roman Antiquity," in Journal of Roman Studies, 77/1987, pp. 139–155

- Juno, Andrea. Modern Primitives. Re/Search #12 (October 1989) ISBN 0-9650469-3-1

- "Tattooing Among Japan's Ainu People". Lars Krutak. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- Lombroso, Cesare (1896) "The Savage Origin of Tattooing," in Popular Science Monthly, Vol. IV., 1896

- Pang, Joey (2008) Tattoo Art Expressions, http://www.tattootemple.hk

- Raviv, Shaun (2006) Marked for Life: Jews and Tattoos (Moment Magazine; June 2006)

- Comparative study about Ötzi's therapeutic tattoos (L. Renaut, 2004, French and English abstract)

- Robley, Horatio (1896) Moko, or, Maori tattooing. London: Chapman and Hall

- Roth, H. Ling (1901) Maori tatu and moko. In: Journal of the Anthropological Institute v. 31, January–June 1901

- Rubin, Arnold (ed.) (1988) Marks of Civilization: Artistic Transformations of the Human Body, Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History

- Sanders, Clinton R. (1989) Customizing the Body: the Art and Culture of Tattooing. Philadelphia: Temple University Press

- Sinclair, A. T. (1909) "Tattooing of the North American Indians," in American Anthropologist 1909/11, No. 3, p. 362-400

- Wianecki, Shannon (2011) "Marked"Maui No Ka 'Oi Magazine.

- Popular and artistic

- Green, Terisa. Ink: The Not-Just-Skin-Deep Guide to Getting a Tattoo ISBN 0-451-21514-1

- Green, Terisa. The Tattoo Encyclopedia: A Guide to Choosing Your Tattoo ISBN 0-7432-2329-2

- Krakow, Amy. Total Tattoo Book ISBN 0-446-67001-4

- Medical

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC's Position on Tattooing and HCV Infection, retrieved June 12, 2006

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Body Art (workplace hazards), retrieved September 15, 2008

- United States Food and Drug Administration, "Tattoos and Permanent Makeup", CFSAN/Office of Cosmetics and Colors (2000; updated [2004, 2006]), retrieved June 12, 2006

- Haley R.W. and Fischer R.P., Commercial tattooing as a potential source of hepatitis C infection, Medicine, March 2000;80:134-151

Notes

- ^ Samoa: Samoan Tattoos, Polynesian Cultural Center

- ^ Tattoo 2. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000

- ^ Roth, H. Ling (1900) On Permanent Artificial Skin Marks: a definition of terms. Anthropological Section of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Bradford, September 11th 1900

- ^ Tattoos: Egyptian Mummies from BMEzine.com Encyclopedia; Tattoos: Pazyryk Mummies from BMEzine.com Encyclopedia

- ^ "Tattoo". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Tattoos, Body Piercings, and Other Skin Adornments

- ^ "Down the Mine" (1937) in the collection "Inside The Whale" (1940), George Orwell

- ^ Adrienne Mayor People Illustrated Archaeological Institute of America Volume 52 Number 2, March/April 1999

- ^ Mifflin, Margot. Bodies of Subversion A secret History of Women and Tattoo. New York City: Juno Books, 1997.

- ^ Deb Acord "Who knew: Mommy has a tattoo", Maine Sunday Telegram November 19, 2006

- ^ The Chicago art exhibition, Freaks & Flash, for example, juxtaposed circus sideshow banners depicting tattooed performers like "The Tattooed Lady" alongside art inspired by the tattoo Renaissance of the 1960s and 1970s.

- ^ "CELEBRITY TATTOOS-BECKHAM, JOHNY DEPP". http://surftolondon.com: Surf to London. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

tattoos like David Beckham's

{{cite web}}: External link in|location= - ^ Laumann AE, Derick AJ (2006), "Tattoos and body piercings in the United States: a national data set", Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 55 (3): 413–21, doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.03.026, PMID 16908345

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. A Portrait of "Generation Next"

- ^ Harris Interactive. Three in ten Americans with a tattoo say having one makes them feel sexier or more artsy

- ^ NYtimes.com

- ^ Ito, Masami, "Whether covered or brazen, tattoos make a statement", Japan Times, June 8, 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Andrew Lichtenstein, Texas Prison Tattoos, retrieved 2007-12-08

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Carroll L, Anderson R (2002), "Body piercing, tattooing, self-esteem, and body investment in adolescent girls", Adolescence, 37 (147): 627–37, PMID 12458698

- ^ Darko Zubrinic (1995), Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ^ Croatianhistory.net

- ^ Customs and folkways of Jewish life, Theodor Herzl Gaster.

- ^ Latter-day Saints commanded to not be tattooed

- ^ "We believe the Bible to be the word of God ..." LDS.org

- ^ 1 Cor 3:10-17; read all these verses to understand the full context

- ^ Sahih Bukhari, Oppressions, Volume 3, Book 43, Number 654

- ^ ‘Abd-Allaah ibn Mas’ood wrote: “May or may not Allaah curse the women who do tattoos and those for whom tattoos are done, those who pluck their eyebrows and nose hairs, and those who file their teeth for the purpose of beautification and alter the creation of Allaah.” (al-Bukhaari, al-Libaas, 5587; Muslim, al-Libaas, 5538)

- ^ "Ruling of Tattoos in Islam". Retrieved 2009-03-25

- ^ Rulings of Grand Ayatullah Sistani - Youth's Issues Posted 18 October 2006

- ^ "Tattooing in Jewish Law". Retrieved 2009-06-25

- ^ Earthtides Pagan Network News, Spring 2010

- ^ a b Tattoo lasers / Histology, Suzanne Kilmer, eMedicine

- ^ a b "Marked" Article by Shannon Wianecki in Maui No Ka 'Oi Magazine, Vol.15 No. 4 July 2011.]

- ^ de:Horst Heinrich Streckenbach tattoo samy, german

- ^ Vgl. Marcel Feige, Das Tattoo-und Piercing Lexikon, S. 282, ISBN 3-89602-209-1.

- ^ "Mythbusters: Can a tattoo explode in an MRI machine?".

- ^ Karen L. Hudson. "Tattoos and MRI Scans". about.com.

- ^ National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Body Art: Preventing Needlestick Injuries. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ^ Tattoos, Renee Kottenhahn, TeensHealth

- ^ Oregon State Health Department

- ^ NYC24.org

- ^ [1]

- ^ Tattoo Post Operative Care

- ^ Tattoos: Risks and precautions to know first - MayoClinic.com

- ^ HIV and Its Transmission July 1999, CDC

- ^ Bruising, retrieved 2009-10-08

- ^ All Experts, New Tattoo - Bruising or Leaking, retrieved 2009-10-08

- ^ Images of Tattoo removal procedure, retrieved 2011-01-12

- ^ "Safety data for silver nitrate". PTCL Safety. Retrieved 3 March 2011.