V for Vendetta (film)

| V for Vendetta | |

|---|---|

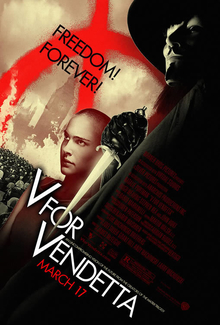

V for Vendetta film poster | |

| Directed by | James McTeigue |

| Written by | The Wachowski brothers (script) |

| Produced by | Joel Silver The Wachowski brothers |

| Starring | Natalie Portman Hugo Weaving Stephen Rea and John Hurt |

| Music by | Dario Marianelli |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates | March 17, 2006 |

Running time | 132 mins. |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $54 million (US)[1] |

V for Vendetta is a 2006 film adaptation of the graphic novel V for Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd. The film was directed by James McTeigue and produced by Joel Silver and the Wachowski brothers, Andy Wachowski and Larry Wachowski, who also wrote the screenplay. The cast includes Natalie Portman as Evey Hammond and Hugo Weaving as V, as well as Stephen Rea as Finch and John Hurt as Sutler. It is also the final film shot by noted cinematographer Adrian Biddle, who died of a heart attack on December 7, 2005.

Filmed in both London, United Kingdom and Berlin, Germany, filming started in early March 2005 in Berlin.[2] Principal photography officially wrapped in early June of 2005.[3] After the release date of November 5, 2005 was delayed, the film opened in conventional as well as IMAX theatres on March 17, 2006.

The film is set in a futuristic London, and the story follows V, an anarchist, who is also on a personal vendetta, pursuing political and social changes in a dystopian society.

Synopsis

The story opens with the story of Guy Fawkes and his unsuccessful attempt to destroy the British Parliament over 400 years ago, then quickly moves to the movie's present day, where government spokesman Lewis Prothero gives a speech showing England to be ruled by a religiously fascist regime.

Evey Hammond, a young woman who breaks curfew, is caught on the street by members of the secret police, known as "fingermen." They are about to rape Evey when a man dressed in black, wearing a Guy Fawkes mask and armed with a set of daggers, intervenes by either incapacitating or killing the fingermen. The man introduces himself to Evey as V and takes her to a London rooftop to show her an event. As the clock strikes midnight on the fifth of November, Tchaikovsky's "1812 Overture" begins playing through the city's PA system and the citizens of London go outside, astounded, to listen to the symphony. In the symphony's climax, The Old Bailey is blown up in a spectacular display of fireworks.

The Norsefire regime, the totalitarian regime of Britain headed by High Chancellor Sutler, explains the destruction of The Old Bailey as a voluntary act of emergency demolition on the part of the government. The police are also dispatched to find Evey, who was identified based on closed-circuit television images showing her in the company of V.

The next day, V takes control of the state controlled British Television Network (BTN) by threatening to bomb it. V plays a recorded message in which he declares that he was responsible for the destruction of the Old Bailey, and urges the populace to take a look at their government and rise up with him a year from today (November 5th), when he will destroy the Parliament building. Coincidentally, Evey works at the BTN. The police under Chief Inspector Eric Finch arrive at the BTN originally with the intent of arresting Evey, but ends up dealing with V instead. V is soon stopped by Lt. Dominic at gunpoint, but Evey maces the officer. Evey is rendered unconscious by the detective, who is himself subdued by V. V takes the unconscious Evey with him.

Evey awakens in V's underground lair, the "Shadow Gallery", which is richly stocked with literature and works of art that he has "liberated" from the censors. He explains to her that she will need to remain with him for the next year, because even the limited information she has about him could conceivably allow the police to locate his den.

V begins killing people, starting with Lewis Prothero, the Norsefire talking head. Finch tries to deduce V's identity based on his victim selection. Finch begins to suspect a cover-up, as the victims all appear to be tied to a former detention facility, whose records are conspicuously absent from the government archives. Evey spends an indeterminate amount of time with V, learning, among other things, that he has been heavily scarred in a fire. She eventually volunteers to assist V in one of his missions, apparently in order to escape. She dresses as a young girl to gain access to a bishop, making V's assault possible, but Evey flees when V attacks the man. She hides with Gordon Dietrich, one of her former superiors at BTN, whom Evey had planned to meet before she was attacked at the beginning of the film. He shows her his collection of contraband and reveals that he is a closeted homosexual who has been forced underground by the Norsefire regime; he tells her that if his house is ever searched, the charge of harboring a fugitive will be the least of his problems, and invites her to stay.

Finch's investigation proceeds, albeit slowly. Speaking with the coroner about one of V's victims, he mentions that V has been leaving a rose with each victim. Recalling that the coroner had once been a botanist, he shows her one of the flowers. She appears rattled, but passes it off by saying that she had thought that breed of rose extinct. At night she is awakened by the appearance of V in her bedroom; she knows V's identity and apologizes to him before V kills her. Finch, having just discovered that the last surviving senior officer from the detention facility is actually the coroner, hurries to her home, but arrives too late to save her. Finch finds and reads her diary, and brings it to the Norsefire council, where Sutler commands him to destroy it and forget its contents. The diary tells the story of the detention camp's medical experiments, which were focused on germ warfare. Almost all of the prisoners died from the experiments. But one, housed in cell "V" (in Roman numerals), not only survived but appeared to gain unusual strength and agility. He apparently destroys the camp through some type of explosion and escapes.

Gordon produces an episode of his show that mocks both the V plot and the Chancellor, reasoning that his popularity will protect him from any truly dreadful consequences. When the police raid his house anyway and attack Gordon, Evey escapes, but is captured by a man in a police commando's uniform. She is held prisoner, shaved, tortured, and interrogated for information concerning V but refuses to divulge anything. She derives strength from a letter she finds hidden in the cell wall. It is the autobiography of Valerie, a former prisoner incarcerated and presumably executed for being a lesbian. When given one last chance to inform on V to escape her execution, Evey says she'd prefer to die. The policeman, who has been hidden in the shadows throughout her interrogations, tells her that her lack of fear makes her free and leaves, leaving the door open. She emerges from the jail cell to find that she has been in V's lair all this time. V has manufactured the entire experience except for the letter from Valerie, which he found in much the same way she did. He wanted Evey to understand his motivations, and to come to grips with her own fear. A hysterical Evey calls V a "monster," but regains her strength and forgives him, promising to see him again before his final attack.

Finch formulates a theory that the diseases researched at the detention centre became the biological weapons used in the terror attacks that propelled Norsefire into power, and that the attacks themselves were staged by Norsefire party members. He is contacted by a man claiming to be the last surviving fingerman involved in the plot. At the man's suggestion, Finch puts Creedy under heavy surveillance. Later, V breaks into Creedy's house and convinces him that Sutler is planning his assassination, based on the surveillance. Creedy agrees to help V take out Sutler when the time comes as relations between Sutler and Creedy worsen considerably. Shortly thereafter Finch discovers that the purported agent has been dead for roughly 20 years, and that V had conned him into investigating Creedy; it is not clear whether the conspiracy theory was true nonetheless or if Finch was merely duped by V. V soon sends "hundreds of thousands" of Guy Fawkes masks to Londoners through the mail. The resulting explosion of "V" sightings puts the nation on edge. Sutler orders a propaganda initiative to remind the population why they need the state and to subdue it through fear again. Finch predicts that under this climate, someone will eventually do "something stupid," bringing chaos, but admits that he doesn't know how to stop V's plan. His predictions prove correct when a fingerman shoots a child wearing a Fawkes mask, setting off a riot.

Evey reappears as promised on the evening of November 4th. After a short dance between the two, V shows her the explosive-laden subway train he plans to detonate under the Parliament Building, but defers the decision whether to destroy the building to her. V feels that he is part of the old world, which along with Sutler's regime is about to be swept away, and Evey is part of the new world that is to come: the people of this new world should have the freedom to decide their own fate, not him. He then leaves to meet Creedy, who (as promised) has abducted Sutler. Creedy shoots Sutler in front of V even as Sutler's prerecorded speech is being broadcast. V then kills Creedy and his men, suffering mortal injuries in the process. V manages to return to Evey, where he dies in her arms. Evey places V's body on the train. Finch eventually locates Evey and the train, but allows Evey to send the train on its way. Above ground, hordes of Londoners dressed as Guy Fawkes advance on Westminster. The armed forces, which had been deployed to stop V's anticipated attack, receive no orders from the Chancellory and (at the last moment) stand down rather than fire on the civilians. Evey takes Finch up on a roof to watch the explosions as V's train detonates destroying the Houses of Parliament as the 1812 Overture again plays over the public address system. Template:Endspoilers

Cast

| Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Natalie Portman | Evey Hammond |

| Hugo Weaving | V |

| Stephen Rea | Eric Finch |

| John Hurt | Chancellor Sutler |

| Stephen Fry | Gordon Dietrich |

| Sinead Cusack | Dr. Delia Surridge |

| John Standing | Bishop Lilliman |

| Tim Pigott-Smith | Creedy |

| Rupert Graves | Dominic |

| Natasha Wightman | Valerie |

| Roger Allam | Lewis Prothero |

| Ben Miles | Dascombe |

| Clive Ashborn | Guy Fawkes |

Background

Conception

Producer Joel Silver acquired the rights to two of Alan Moore's texts, V for Vendetta and Watchmen in 1988, though Watchmen changed hands over the years, he did however hold on to V for Vendetta.[4]

The Wachowski brothers were known to be huge fans of the graphic novel V for Vendetta, and first wrote a draft for the script in the 1990s before they worked on The Matrix, with which V for Vendetta shares some thematic elements. [5]

Despite the Wachowskis both being fans of Alan Moore and his graphic novels, Moore has explicitly disassociated himself from the movie adaptation, continuing his ongoing dispute over film adaptations of his works[6]. He ended cooperation with his publisher, DC Comics, after its corporate parent, Warner Bros., despite DC's urging, failed to retract statements that Moore called "blatant lies" about his supposed endorsement of the movie in a press release by producer Joel Silver. Moore complained that the script runs contrary to the entire theme of his original work, which was to place two political extremes (fascism and anarchism) against one another, while allowing readers to decide for themselves whether V was right in his actions or simply insane. He argues that this "little moral drama" has been reduced to debating "current American neo-conservatism vs. current American liberalism". [7] He has called this decision "imbecilic" and says he views the script as containing "plot holes you couldn't have got away with in Whizzer and Chips in the nineteen sixties. Plot holes no one had noticed." [8] As per his wishes, Moore's name does not appear in the film's closing credits.

Despite Moore withdrawing his support from the project, co-creator and illustrator David Lloyd supports the film adaptation, opining that the script is very good and that Moore would only ever be truly happy with a complete book to screen adaptation. [9]

Casting

Natalie Portman, who plays Evey Hammond, signed on for the film in January 2005,[10] following a highly successful year during which she starred in both Garden State and Closer. Director James McTeigue first met Portman on the set of Attack of the Clones, where he worked closely with her as assistant director of the film. She received top billing for the film. Portman looked forward to shaving her head totally bald for the role of Evey Hammond during the torture scenes, stating that she has wanted to do it for a long time. In preparing for the role of Evey, Portman worked with Barbara Berkery (a dialectologist who had also worked with Gwyneth Paltrow) to perfect her English accent.

Hugo Weaving plays V, although James Purefoy was originally cast as V but left the project six weeks into filming; the exact details or the reason for his departure have not been confirmed, but has been described as 'creative differences' with members of the production team. It was also hinted in an article from Time magazine that he left because he could not stand perpetually wearing the mask. He was replaced as V by Weaving, who previously worked with Joel Silver and the Wachowski brothers on The Matrix.

John Hurt's role as Chancellor Sutler was a role reversal for him, as he played the part of Winston Smith, a victim of the state in the film adaptation of 1984.

Marketing and release

On June 15th, members of the cast and crew attended Comic-Con in San Diego, making one of their first major appearances, it was at the Comic-Con that the trailer was shown for the first time. Early July saw the first poster for the film distributed to theatres. On July 22, the first trailer for the film became available on the film's official website. Early posters had taglines such as "People should not be afraid of their governments. Governments should be afraid of their people." as well as "An uncompromising vision of the future from the creators of The Matrix trilogy".

The film was originally scheduled to be released on the weekend of November 5, 2005 with the tagline "Remember, remember the 5th of November", the first line of a traditional British rhyme recounting the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot to blow up Parliament in 1605. The 5th of November 2005 was 400th anniversary of the infamous plan. The Gunpowder Plot imagery is leant on extensively by both the book and the film, with V behaving as a latter-day Guy Fawkes (albeit more successful) in his destruction of the Houses of Parliament, an event which, in the original graphic novel, took place on that same anniversary in 1997 with V reciting the rhyme and dressed as Guy Fawkes.

However, in late 2005, the announced release date was pushed back, to March 17, 2006. Some have speculated this is due to the London bombings on 7 July and 21 July. The film-makers have denied this, and say it was delayed to allow more time for production, explaining that the visual effects would not be completed in time. Many believe that the Wachowski Bros. were so superstitious that they begged the studio to delay the film until March - the same month that the first Matrix film was released. Either way, the creative marketing angle lost much of its value, although it could still be used for the film's home video release should the distributor select a November release date.

On November 15, a special internet campaign was launched following the delay of the film. Four never-before-seen posters for the film were distributed to four independent websites. All four of these new posters sported a new tagline, "Freedom! Forever!". These new posters, or rather sets of posters have been seen presented in such a fashion that is reminiscent of propaganda-like art. On December 15, a new trailer became available online. Warner Bros. were to promote three of its biggest films of 2006 at Super Bowl XL: Poseidon, 16 Blocks and V for Vendetta. Major theatres decorated the exterior of their buildings with flags featuring the Fingermen logo.

Music

The original score for the film is by Dario Marianelli. The soundtrack also features three other songs: "Cry Me a River" by Julie London, "I Found A Reason" by Cat Power and "Bird Gerhl" by Antony and the Johnsons. The soundtrack was released on March 21, 2006 by Astralwerks Records. It was thought that Massive Attack would contribute to the soundtrack, but they had to pull out due to scheduling clashes.

There were several songs which were not included on the V for Vendetta soundtrack, including "Street Fighting Man" by the Rolling Stones which appeared during the end credits, as well as Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture and Beethoven's Symphony No.5, both of which played important roles in the film.

Novelization

A novel by Steve Moore (no relation to original author, Alan Moore) was released in addition to the film.[11] It is a novelization of the adapted screenplay, not the graphic novel.[12]

Differences from graphic novel

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. |

Some fans of the original comic and graphic novel expressed concerns about the film adaptation, based on less-than-faithful film adaptations of Moore’s work such as From Hell and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, along with the film portrayal of John Constantine, a character whom Moore created for the Swamp Thing series. However, Vendetta has been described as "easily the most faithful and literal adaptation of an Alan Moore graphic novel to date".[13] As noted previously, Moore has distanced himself from the Vendetta film project. Though the film stands without support from Moore, graphic novel illustrator David Lloyd commented on the level of faithfulness to the original source by saying that "Watching some of the scenes was like seeing a painting I've done come to life"[14]. Lloyd, who has been vocal in his approval of the film also said that it was important that the Wachowskis were original fans of the novel.

The original adaptation written by the Wachowskis during the end of their Matrix saga was “almost a blow-for-blow retelling of the graphic novel”,[15] director James McTeigue recalls. So the screenplay was rewritten to move the story forward, making present day London around 2020. Evey Hammond's background was apparently altered and she appears older than she originally did in the graphic novel. Natalie Portman, who plays Evey, read the graphic novel after reading the screenplay said that “it really keeps to the graphic novel, it keeps the integrity of the story and a lot of the dialogue is directly from it”.[16] As well, several of the characters' professions have changed: Evey is no longer a desperate, would-be prostitute but is now an assistant at the government-controlled television station (British Television Network, or BTN) while Gordon is a BTN talk show host.

Setting

The original graphic novel mentions that the United Kingdom has a Queen. In the movie, there is no mention of any Queen or Monarch. To muddy the waters further, the police shields and the military shields no longer have a Crown but the rank insignia does. It is possible that, in the movie scenario, there is no longer a British monarch.

The plot has also been updated (or heavily adapted, depending one's point of view) to current times. Rather than coming to power in the UK as a result of a limited nuclear war (as in the comic), in the film it is vaguely explained that the ultra-right wing totalitarian government came to power when "America's war" (presumably an expanded War on Terrorism), which the UK was involved in, spiraled out of control. Protests, riots, and acts of terrorism became rampant, and society began to crumble; there was a backlash to maintain order, and dissidents started being held en masse in detention centers. Sutler started out as a Conservative defence minister, but as social conditions worsened he broke away to lead his own reactionary party, "Norsefire". The transition to fascism in the comic was far less orderly. The Labour Party defeated Thatcher in her first bid for re-election, and disarmed the UK's nuclear force. In the subsequent nuclear exchange between NATO and the Soviet bloc, the UK emerges without being hit by nuclear weapons. However, the nuclear winter causes massive environmental effects, leading to famine and massive flooding. Fascist groups coalesce and restore order, being hailed as saviors. The backstory in the comic is fairly brief.

The openly-fascist Norsefire comes to power in the film through the ordinary political process, with in excess of 80% of the vote. The mechanism is elaborated in the film to a much greater extent than was ever discussed in the comic. It is worth noting, however, that much of the following explanation comes from Finch's speculation that the biological attacks were a Reichstag fire ploy. His fears are "confirmed" by a discussion with one of the agents involved, but it is later made clear that the agent was 20 years dead, and V was manipulating Finch to get to Creedy. Norsefire, staged a plan that would sweep them into full control of the nation: they conducted horrific medical experiments on prisoners in the detention centers to perfect a deadly virus. They then released the virus to fake a terrorist attack by foreign religious extremists. To maximize its effect, they released it in a water treatment plant called Three Waters, in a London Underground station, and in St. Mary's Primary School. The "St. Mary's virus" quickly killed almost 100,000 people in Great Britain, and the populace was gripped by fear. Several "terrorists" -- scapegoats under this interpretation -- were tried and executed. Norsefire then promised to bring back security against the new "terrorist threat". Of course, at the same time that Norsefire developed the virus in the detention centers they also made the cure, and upper party members bought stock in the pharmaceutical companies that would later mass produce it, becoming very rich in the process. Not long after the biological attack and their ascension to power, the public was informed that a cure was "miraculously" discovered, and distributed throughout the country (it is implied that the virus spread across the globe, but Norsefire didn't share the cure). Sutler was then elected to the new office of High Chancellor. The pharmaceutical profits, the rapid execution of the terrorists, the demise of several fingermen shortly after the "attacks" (who were all eyewitnesses), and the existence of the biological experiments at the Larkhill detention facility, all seem to be incontrovertible within the world of the movie (neither V nor Norsefire could have faked these facts).

The rest of the world is only passingly mentioned, although it is stated that at least the USA (referred to as the "former United States," not unlike "the former Soviet Union") has fallen upon desperate times. Early in the movie it is mentioned that the USA has become so desperate for medical supplies that it has sent Britain a tremendous amount of grain and tobacco in a bid for aid, and at least by the end of the movie has broken out into its second civil war, perhaps a consequential result of the war the United States led in the Middle East; however the Voice of London is a propaganda tool, and little it says can be believed. It can be assumed we know little of the actual state of affairs outside the country.

The Leader of the "Party" has a different name, Sutler, which has the connotation of a tradesman working for the Army, though the name in the novel is Susan. Sutler is also a combination of the original name and Hitler. But Sutler seems to be inspired by Oswald Mosley and its movement likewise inspired by the British Union of Fascists.

It appears that the original idea of a nuclear war has been exchanged for one of bio-weapons. Alan Moore later states in the foreword to the trade paperback edition of V for Vendetta that scientists now felt that even a "limited" nuclear war was not survivable. Thus biological weapons would today be considered more plausible.

The name of the government party, Norsefire, is only used passingly in the film. It is said that Sutler originally came to power in the Conservative Party, but a chart of election results show that Sutler broke away and formed his own party ("Labour", "Conservative" and "Norsefire" are shown). The party itself does not appear to be openly fascist as in the comics, and also seems to be anti-homosexual and anti-Muslim, while we know for certain that the novel government is also against black people and Jews, although the Aryan hero, Storm Saxon makes a brief appearance. It is still vaguely implied in the film that the Party is extremely racist, as when Creedy questions Finchs's loyalty based solely on the fact that Finch's mother was Irish, Prothero uses the term "paddy" about a crew member on his show, black people are seen at Larkhill etc. The computer system "Fate", which played an important role in the graphic novel, is also absent.

Plot

The film tones down or eliminates V's anarchist philosophy and casts him as more of a generic freedom fighter. The violence of V's character has also been toned down; for example during the opening fight scene he only stabs one of the fingermen who try to rape Evey, and the lethality of his ruse in the BTN Propaganda room has been reduced (only one of the hostages is shot by the police, and apparently not fatally, although it is worth noting that he did leave a rather large timebomb). While in the graphic novel V often kills using only his fingers, in the film his preference is for throwing knives. The majority of V's assassinations occur off-camera; his initial surprise attack on his victims is portrayed in the film, but the film then tends to cut to the police finding the dead victim. The only assassinations shown from start to finish are those of Dr. Surridge, whose death is painless, and of Creedy, during which V takes on several armed men (Creedy himself actually kills Sutler). V is also responsible for the death of a sizable number of police officers during his cunning escape from the British Television Network building, when he uses many live police officers as human shields to block the bullets of their comrades, until they empty their clips and V counterattacks with his daggers, but this could be viewed as just "necessary" steps he took to protect himself; when Dominic is sprayed in the eyes with mace at the end of V's escape and thus immobilized, V simply knocks him unconscious rather than killing him. The only men V kills on-camera are armed agents of the fascist state.

As a character, V appears to be less mysterious, and much more direct in his conversation. As noted below, in the comic there is some ambiguity about the identity of the Larkhill inmate that eventually becomes V, the movie does not speculate openly on the identity of the prisoner in Cell V. In the film, it was bio-warfare experiment side effects which gave him his superior athletic and mental gifts (in the comic, it was synthesized hormone experiments on prisoners and the desired result was actually to find ways of creating super soldiers). We have no implication of his past having anything to do with social unrest that would have had him arrested. Indeed, it is not until the virus has a reverse effect on him that he becomes the character we see in the story. Whereas in the film he introduces himself to Evey as simply "V", when asked by Evey who he is in the comic, he responds: "Me? I'm the king of the twentieth century. I'm the bogeyman. The villain... the black sheep of the family." His moral ambiguity somewhat survived the adaptation, although arguably he is more clearly a protagonist, where in the original comics he could also be said to be the primary antagonist. In the words of Alan Moore, V's actions were left "morally ambiguous" [17] so that readers could consider for themselves whether his actions were heroic or atrocious. This issue, however, is left lingering in the film as well, often through comparison to The Count of Monte Cristo. Evey notes that she feels sorry for Mercedes, because Dantes clearly cares more about revenge than he does about her; V is poleaxed by her statement. Arguably, V loves neither British liberty nor Evey herself so much as he loves his revenge on Norsefire, and like Dantes he seems oblivious to that.

Evey has also had some changes; she has been aged from the sixteen in the graphic novel. She has a brother in the movie, to add to the virus plot that is absent from the novel. Her mother died from illness in the novel and her father was taken away for having belonged to a socialist organization when he was younger, while in the movie both are taken away for their involvement in protests. In the novel, she is forced to work packing matches into boxes for shipment, and then begins working at a munitions factory, while in the movie she is at a child reclamation camp and then works for the BTN. The work at the munitions factory pays so little that when V initially rescues her, she was making her first attempt at soliciting a man for sex (badly). In general, Evey in the novels is much more trusting of V immediately, including the fact that she doesn't voluntarily leave the Shadow Gallery, but is removed from it wearing a blindfold after theorizing that V could be her father. The scenes showing Evey imprisoned, Valerie's memoirs and Evey's release and transformation are taken almost verbatim from the original graphic novel.

The film plays up a romantic angle between V and Evey in the style of The Phantom of the Opera. In the original graphic novel, V's statement to Evey that he loves her appeared in context more like the statement of universal love that Valerie's letter ends with (appropriately enough, given the speculation that V might in fact be Valerie in the comic); V's identification as the prisoner from cell V is ambiguously suggested in the comic but quite clear in the film. By flatly having V declare love for Evey, it removes another ambiguous aspect of the novel — namely, that V's "crime" may have been being homosexual. Additionally, the suggestion that V may actually be Evey's father is completely nullified by this change in story.

Inspector Finch's character is much more brooding and introspective, rather than the obsessive legalist he is depicted as in the graphic novel. Instead of killing V as he does in the original work, Finch even goes so far as to allow Evey to send V's body on its way to blow up Parliament. Much of the rivalry between the different state institutions was deleted, including the entire Rose Almond subplot (in the graphic novel, she assassinates the leader).

V starts by rescuing Evey, then blowing up the Old Bailey on November 5, (not Parliament as in the original graphic novel). He announces his intent to blow up Parliament one year hence, and the plot with Evey's imprisonment, V's killing of veterans of Larkhill, and Finch's investigation continues roughly as in the book. The climax of the film is somewhat altered: V has a climactic shootout with Creedy rather than the brief (though fatal) skirmish with Finch that appears in the comic; meanwhile, in one of the larger departures from the original work, the British army is confronted by a large crowd of unarmed protesters, and ultimately stands down. In the comic, the crowd does not wear Guy Fawkes masks, but a riot is still brewing. After receiving Finch's report that V has been fatally wounded, the police report over loudspeakers that V is dead, and the crowd hesitates. However, after Evey lays V's body in state, she takes one of his spare costumes from the Shadow Gallery, and effectively becomes "V"; Evey-as-V appears on a rooftop and declares to the large crowd below that the reports that "he" died were just more lies, and the reinvigorated crowd rushes the barricades; a bloody riot ensues. The final ending, with V given a funeral on a tube train which explodes underneath 10 Downing Street, is altered to be the bombing of Parliament, with a large crowd gathered, on V's instructions, at a safe distance to watch the fireworks, all wearing Guy Fawkes masks and gowns. Presumably, the change was so that Parliament would be blown up at the climax of the film. Interestingly, the film takes place over one year, so Parliament is blown up on the fifth of November, and finalizes the defeat of Sutler. Template:Endspoilers

Symbolism and cultural references

The film takes imagery from many past totalitarian themes both real and fictional, including Nazi Germany and George Orwell's 1984. Critics and commentators have also noted that the film contains numerous references to modern-day events and symbols surrounding the current American administration as well, include the War on Terrorism, the War in Iraq.[18][19] [20][21][22]

Modern US references:

- The "black bags" worn by the prisoners in Larkhill may reference the black bags worn by prisoners at Abu Ghraib in Iraq and Guantánamo Bay in Cuba.

- Early on in the film, public loud-speakers announce that London is under a yellow-coded curfew alert. This is similar to the US Government's color-coded Homeland Security Advisory System.

- One of the forbidden items in Gordon's secret basement is a protest poster with a mixed US–UK flag with a swastika and the title "Coalition of the Willing, To Power!" This is likely a reference to the real Coalition of the Willing that was formed for the Iraq War. At the same time, it also appears to be a reference to Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of Will to Power.

- The media is portrayed as being highly subservient to government propaganda, which evokes common criticisms about the American media, namely that it has been too eager to support the government's line regarding threats and other issues. In the culture of fear montage of news video clips shown after Sutler orders his council to "remind the public why they need us," the BTN refers to avian flu as a pandemic.

- The "Voice of London" talk show host Lewis Prothero can similarly be seen as evoking the image of conservative American pundits like Bill O'Reilly and Rush Limbaugh, particularly with Limbaugh and the character's drug use.

Other historical and cultural references:

- Valerie was sent to a detention facility for being a lesbian and was then tortured and had medical experiments performed on her. This is similar to Nazi Germany's treatment of gays during the Holocaust, where homosexual men were sent to concentration camps and experimented upon by Nazi doctors, in order to search for any biological means to eradicate homosexuality.

- The Hitler-like Sutler primarily appears on large video screens in the film, reminiscent of Big Brother in Nineteen Eighty-Four. The state's extensive use of mass surveillance on its citizens (including closed-circuit television) is also reminiscent of the film. This is particularly noteworthy as London currently has the world's highest concentration of CCTV.[23]

- The Norsefire government's "Articles of Allegiance" may be an allegorical reference to the Oath of Supremacy, a Tudor-era Oath of allegiance that was one (of many) grievances of (Catholic) Guy Fawkes leading to the 1605 Gunpowder Plot. It may also be a allusion to a proposal made early in the 21st century by the British Labour Party for the institution of an oath of allegiance for immigrants. Also, the initials "NF" of the Aryan sounding Norsefire party, may also be a reference to the British Fascist party the National Front.

- "V" is associated with the World War II slogan "V for Victory". When V confronts Creedy in his greenhouse, he plays the first movement of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. The opening notes of the symphony were used as a call-sign in European broadcasts by the BBC during World War II, because their rhythmic pattern resembled the letter "V" in Morse code (···–). Vi vil vinne (We will win) was also a slogan of the Norwegian Resistance, abbreviated as "V".

- The red-on-black "V" symbol resembles an inverted "A" symbol for anarchy.

- The memorial to the St. Mary's disaster shows children dancing in a circle. This is reminiscent of a famous memorial showing dancing girls in Stalingrad, which was one of the few structures left standing after the Nazi attack on the city [1] It is likely also a reference to children playing "Ring Around the Rosy", a game which involves a rhyme derived from the symptoms and effects of the black death.

- Norsefire uses the Cross of Lorraine as their party symbol. This was the symbol used by the Free French Forces in WWII, and was chosen because it was a traditional French symbol of patriotism that could be used as an answer to the Nazis's Swastika. The flags could also be seen as having a Nordic style design.

- V's pseudonym, 'Rookwood', is the name of one of the original 1605 gunpowder conspirators, Ambrose Rookwood. There is also brief mention of two others, Catesby and Percy.

- At one point V says something to the effect of "what kind of revolution is this if you cannot dance?" referencing Emma Goldman

Reception

Box office

V for Vendetta opened on March 17, 2006 in 3,365 theatres in the United States as well as the United Kingdom and six other countries. The film is expected to be theatrically distributed in 34 countries.[24] The film led the United States box office on its opening day, taking in an estimated $8,350,000.[1] V for Vendetta remained the number one film for the remainder of the weekend, taking in an estimated total of $25,642,340;[1] its closest rival was Failure to Launch, which took in $15,815,000.[25] V for Vendetta is also being shown at many IMAX theaters: it opened in 56 North American theatres and had a strong interest, grossing $1.36 million during the opening three days.[26] Despite the film taking place in Great Britain, the film did not reach number one at their box office on the opening weekend; instead, The Pink Panther took the number one spot.

Although the film has yet to open in all markets, the film opened in a number of countries at roughly the same time as the debuts in the US and UK, either a day before or after.[24] The film debuted at number one in South Korea, Taiwan, Sweden, Singapore and the Philippines.[27] The film has thus far grossed (USD) $49,360,758 in the United States and $17,600,000 elsewhere, for a worldwide gross of $66,960,758.[28]

Critical

Reviews prior to the release of the film, early reviews, namely around the Berlin Film Festival were positive. Despite Alan Moore's complaints, the critical reception of the film has largely been positive. For instance, the movie review summary website, Rotten Tomatoes, has given the film 75% Fresh approval, and Ebert & Roeper have given the film two thumbs up, it also entered the IMDb top 250 at #237 after three days and as of 31 March, 2006 stands at #226 at a rating of 8.1/10 after two weeks days and roughly 23,000 votes.[29] Positive reviews have cited great acting and writing,[30] whilst the controversial aspects have also been praised, critics appreciating the film for being daring and calling it the "most politically charged film since Fahrenheit 9/11"; it has also been described as a "political thriller that will literally take your breath away".[31]

One of the most negative reviews came from Michael Medved of conservative radio, who called the film "V for vile, vicious, vacuous, venal, verminous and vomitaceous." Medved also said that the audience will lose interest about halfway through the film and that it has a confusing ending. [32]

Political

Although the film is an adaption of a text that was written during the 1980s, as mentioned above, some have viewed the film as a social critique of today's society. As expected, Vendetta's thought-provoking storyline has seen it come under criticism for its portrayal of anti-government fighters. Before its theatrical release, some were ready to label it as a glorification of terrorism. On opening day, Reuters echoed the sentiment calling, V for Vendetta "a movie whose heroes are terrorists,"[33] although it should be noted that the Reuters article itself referred mainly to an expected reaction and was not disparaging the film.

Many libertarians, especially at the Mises Institute's LewRockwell.com see the film as a positive depiction in favor of a free society with limited government and free enterprise, citing the state's terrorism as being of greater evil and rationalized by its political machinery, while V's acts are seen as 'terroristic' because they are done by a single individual. [34]

Some anarchist groups decided to use the release of the film as a chance to gain publicity for anarchism as a political philosophy. In New York City, anarchists began distributing literature outside theaters during sneak previews on March 16.[35] However, anarchists have remained ambivalent about the film itself, with a number feeling the work has been censored. One of the more popular fliers states that the anarchist message of the original graphic novel has been "watered down" [36] in order to satisfy a mass Hollywood audience.

The film has also met with disapproval by some socialist circles, who see the movie as an expression of revolutionary spontaneity and the "great savior" individual who liberates the oppressed masses from fascism, rather than a collective act of revolution from the entire population. However, some see this view as a misconception, given this "great savior" actually represents ideas of revolution and of free minds.[37]

Trivia

- The Swedish acting company Stockholm Blodbad staged a multi-media live action performance of V for Vendetta called "Landet där man gör som man vill" or "The-Land-of-Do-As-You-Please" in December 2000. [38] Pictured here:[2]

- Prime Minister Tony Blair's son Euan Blair worked on the film's production and is said to have helped the filmmakers obtain unparalled filming access to Westminster. This drew criticism for Blair from MP David Davis due to the content of the film. The makers of the film deny Mr Blair's son's involvement in the deal. [39]

- The domino scene (where V tips over black and red dominoes to form a giant letter V) involved 22,000 dominoes, was assembled by 4 professional domino assemblers, and took 200 hours to set up. [40]

- The Sutler skit on Deitrich's show uses many of the conventions of The Benny Hill Show, including its trademark undercranking and use of Yakety Sax.

- "V's 'V' monologue" contains 55 words beginning with V in the monologue. This could be shown as "V V" or two Roman numeral 5's next to each other (but only if transliterated directly from Arabic numerals - the number fifty-five itself would be shown as "LV"). However, 55 is also the product of 11 times 5 - and the Fifth of November is represented as 11-5. "V's 'V' monologue" from the movie is located on Wikiquote

- V's "Shadow Gallery", which holds items banned by the Norsefire regime, contains Jan Van Eyck's The Arnolfini Portrait, Bacchus and Ariadne by Titian, a Mildred Pierce poster and John William Waterhouse's The Lady of Shalott.

- The scenes taking place in the abandoned London Underground station were filmed at the abandoned Aldwych tube station.

Notes

- ^ a b c "V for Vendetta (2006) - Daily Box Office". boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 18 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "News entry notes when filming will begin". natalieportman.com. Retrieved 16 December.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "PHOTOGRAPHY COMPLETE". vforvendetta.com. Retrieved 16 December.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V for Vendetta news". vforvendetta.com. Warner Brothers. Retrieved 31 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Trivia for V for Vendetta". imdb.com. amazon.com. Retrieved 16 December.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Alan Moore: Our greatest graphic novelist". The Independent. 19 March, 2006.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "A FOR ALAN, Pt. 1: The Alan Moore interview". MILE HIGH COMICS presents THE BEAT at COMICON.com. GIANT Magazine. Retrieved 21 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "MOORE SLAMS V FOR VENDETTA MOVIE, PULLS LoEG FROM DC COMICS". comicbookresources.com. Retrieved 5 June.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V AT COMIC CON". vforvendetta.com. Retrieved 14 November.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "P for Portman?". dc-on-film.com. Retrieved 16 December.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Moore, Steve (2006). V for Vendetta. Pocket Books. ISBN 1416516999.

- ^ Moore, Alan (2005). V for Vendetta (New Edition). Titan Books. ISBN 1845761820.

- ^ "V For Vendetta". comingsoon.net. Retrieved 6 February.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Danny Peary (April 2006). ""FROM PAGE TO SCREEN..."". Filmink Magazine.

- ^ "vforvendetta.com". ABOUT THE STORY. Retrieved 7 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V FOR VENDETTA: TALKING WITH NATALIE PORTMAN". comicbookresources.com. Retrieved 7 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "A FOR ALAN, Pt. 1: The Alan Moore interview". GIANT Magazine. Retrieved 19 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Owen Gleiberman (March 15, 2006). "Review: V for Vendetta". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ "Gunpowder, treason and plot". March 19, 2006.

- ^ Owen Gleiberman. "EW review: 'V for Vendetta,' O for OK". CNN. Time Warner.

- ^ David Denby (March 13, 2006). "BLOWUP: V for Vendetta". The New Yorker. Conde Nast.

- ^ Debbie Schlussel (March 13, 2006). ""V" for Vicious Propaganda". FrontPage.

- ^ "Blast proof city: The threat of terrorism could help to reshape the face of London". Builder And Engineer. Retrieved 2006-03-31.

- ^ a b "Release dates". imdb.com. amazon.com. Retrieved 18 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Failure to Launch (2006) - Daily Box Office". boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 20 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V for Vendetta Posts Strong IMAX Opening". vfxworld.com. Retrieved 22 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "'V' for (international) victory". Boston Herald. Retrieved 22 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V for Vendetta (2006)". boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 22 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V for Vendetta (2005)". imdb.com. amazon.com. Retrieved 20 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V for Vendetta showcases superb acting, writing". The Exponent. Retrieved 22 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V for Vendetta". yourmovies.com.au. Retrieved 22 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V FOR VENDETTA" (PDF). Michael Medved's Eye on Entertainment. michaelmedved.com. Retrieved 18 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ ""V for Vendetta" a revolutionary call to arms". Reuters. March 16, 2006.

- ^ ""V for Vendetta"". lewrockwell.com. Retrieved 20 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "infoshop.org". V for Vendetta is about Anarchy. Retrieved 19 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "A for Anarchy flier". aforanarchy.com. Retrieved 20 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Stage version of V for Vendetta". shadowgalaxy.net. Retrieved 27 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "The How E put the V in Vendetta". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "The ABCs of V for Vendetta". rockymountainnews.com. Retrieved 24 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

Official

Resources

Fansites