Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry |

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental disorder.[1] It is characterized primarily by "the co-existence of attentional problems and hyperactivity, with each behavior occurring infrequently alone" and symptoms starting before seven years of age.[2]

ADHD is the most commonly studied and diagnosed psychiatric disorder in children, affecting about 3 to 5 percent of children globally[3][4] and diagnosed in about 2 to 16 percent of school aged children.[5] It is a chronic disorder[6] with 30 to 50 percent of those individuals diagnosed in childhood continuing to have symptoms into adulthood.[7][8] Adolescents and adults with ADHD tend to develop coping mechanisms to compensate for some or all of their impairments.[9] It is estimated that 4.7 percent of American adults live with ADHD.[10] Standardized rating scales such as the World Health Organization's Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale can be used for ADHD screening and assessment of the disorder's symptoms' severity.[11]

ADHD is diagnosed two to four times more frequently in boys than in girls,[12][13] though studies suggest this discrepancy may be partially due to subjective bias of referring teachers.[14] ADHD management usually involves some combination of medications, behavior modifications, lifestyle changes, and counseling. Its symptoms can be difficult to differentiate from other disorders, increasing the likelihood that the diagnosis of ADHD will be missed.[15] In addition, most clinicians have not received formal training in the assessment and treatment of ADHD, in particular in adult patients.[15]

ADHD and its diagnosis and treatment have been considered controversial since the 1970s.[16] The controversies have involved clinicians, teachers, policymakers, parents and the media. Topics include ADHD's causes, and the use of stimulant medications in its treatment.[17][18][19] Most healthcare providers accept that ADHD is a genuine disorder with debate in the scientific community centering mainly around how it is diagnosed and treated.[20][21][22] The American Medical Association concluded in 1998 that the diagnostic criteria for ADHD are based on extensive research and, if applied appropriately, lead to the diagnosis with high reliability.[23]

Classification

ADHD may be seen as one or more continuous traits found normally throughout the general population.[24] It is a developmental disorder in which certain traits such as impulse control lag in development. Using magnetic resonance imaging of the prefrontal cortex, this developmental lag has been estimated to range from 3 to 5 years.[25] However, the definition of ADHD is based on behaviour and it does not imply a neurological disease.[24] ADHD is classified as a disruptive behavior disorder along with oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder and antisocial disorder.[26]

ADHD has three subtypes:[27]

- Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive

- Most symptoms (six or more) are in the hyperactivity-impulsivity categories.

- Fewer than six symptoms of inattention are present, although inattention may still be present to some degree.

- Predominantly inattentive

- The majority of symptoms (six or more) are in the inattention category and fewer than six symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity are present, although hyperactivity-impulsivity may still be present to some degree.

- Children with this subtype are less likely to act out or have difficulties getting along with other children. They may sit quietly, but they are not paying attention to what they are doing. Therefore, the child may be overlooked, and parents and teachers may not notice symptoms of ADHD.

- Combined hyperactive-impulsive and inattentive

- Six or more symptoms of inattention and six or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity are present.

- Most children with ADHD have the combined type.

Signs and symptoms

Inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity are the key behaviors of ADHD. The symptoms of ADHD are especially difficult to define because it is hard to draw the line at where normal levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity end and clinically significant levels requiring intervention begin.[15] To be diagnosed with ADHD, symptoms must be observed in two different settings for six months or more and to a degree that is greater than other children of the same age.[28]

The symptom categories of ADHD in children yield three potential classifications of ADHD—predominantly inattentive type, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type, or combined type if criteria for both subtypes are met:[15]: p.4

Predominantly inattentive type symptoms may include:[29]

- Be easily distracted, miss details, forget things, and frequently switch from one activity to another

- Have difficulty maintaining focus on one task

- Become bored with a task after only a few minutes, unless doing something enjoyable

- Have difficulty focusing attention on organizing and completing a task or learning something new or trouble completing or turning in homework assignments, often losing things (e.g., pencils, toys, assignments) needed to complete tasks or activities

- Not seem to listen when spoken to

- Daydream, become easily confused, and move slowly

- Have difficulty processing information as quickly and accurately as others

- Struggle to follow instructions.

Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type symptoms may include:[29]

- Fidget and squirm in their seats

- Talk nonstop

- Dash around, touching or playing with anything and everything in sight

- Have trouble sitting still during dinner, school, and story time

- Be constantly in motion

- Have difficulty doing quiet tasks or activities.

and also these manifestations primarily of impulsivity:[29]

- Be very impatient

- Blurt out inappropriate comments, show their emotions without restraint, and act without regard for consequences

- Have difficulty waiting for things they want or waiting their turns in games

Most people exhibit some of these behaviors, but not to the degree where such behaviors significantly interfere with a person's work, relationships, or studies—and in the absence of significant interference or impairment, a diagnosis of ADHD is normally not appropriate. The core impairments are consistent even in different cultural contexts.[30]

Symptoms may persist into adulthood for up to half of children diagnosed with ADHD. This rate is difficult to estimate, as there are no official diagnostic criteria for ADHD in adults.[15] ADHD in adults remains a clinical diagnosis. The signs and symptoms may differ from those during childhood and adolescence due to the adaptive processes and avoidance mechanisms learned during the process of socialisation.[31]

A 2009 study found that children with ADHD move around a lot because it helps them stay alert enough to complete challenging tasks.[32][33]

Comorbid disorders

Inattention and "hyperactive" behavior are not necessarily the only problems in children with ADHD. ADHD exists alone in only about 1/3 of the children diagnosed with it. The combination of ADHD with other conditions can greatly complicate diagnosis and treatment. Many co-existing conditions require other courses of treatment and should be diagnosed separately instead of being grouped in the ADHD diagnosis.

There is a strong association between persistent bed wetting and ADHD[34] Multiple research studies have also found a significant association between ADHD and language delay.[35] Anxiety and depression are some of the disorders that can accompany ADHD. Academic studies, and research in private practice suggest that depression in ADHD appears to be increasingly prevalent in children as they get older, with a higher rate of increase in girls than in boys, and to vary in prevalence with the subtype of ADHD. Where a mood disorder complicates ADHD, it would be prudent to treat the mood disorder first, but parents of children with ADHD often wish to have the ADHD treated first, because the response to treatment is quicker.[36]

Some of the associated conditions are:

- Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, both of which characterized by antisocial behaviors such as stubbornness, aggression, frequent temper tantrums, deceitfulness, lying, or stealing,[37] inevitably linking these comorbid disorders with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD); about half of those with hyperactivity and ODD or CD develop ASPD in adulthood.[38]

- Borderline personality disorder, which was according to a study on 120 female psychiatric patients diagnosed and treated for BPD associated with ADHD in 70 percent of those cases.[39]

- Primary disorder of vigilance, which is characterized by poor attention and concentration, as well as difficulties staying awake. These children tend to fidget, yawn and stretch and appear to be hyperactive in order to remain alert and active.[37]

- Mood disorders. Boys diagnosed with the combined subtype have been shown likely to suffer from a mood disorder.[40]

- Bipolar disorder. As many as 25 percent of children with ADHD have bipolar disorder. Children with this combination may demonstrate more aggression and behavioral problems than those with ADHD alone.[37]

- Anxiety disorder, which has been found to be common in girls diagnosed with the inattentive subtype of ADHD.[41]

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder. OCD can co-occur with ADHD and shares many of its characteristics.[37]

In adults

Researchers found that 60 percent of the children diagnosed with ADHD continue having symptoms well into adulthood.[42][43] Many adults, however, remain untreated.[42] Untreated adults with ADHD often have chaotic lifestyles, may appear to be disorganized and may rely on non-prescribed drugs and alcohol to get by.[44] They often have such associated psychiatric comorbidities as depression, anxiety disorder, substance abuse, or a learning disability.[44] A diagnosis of ADHD may offer adults insight into their behaviors and allow patients to become more aware and seek help with coping and treatment strategies.[43] There is controversy amongst some experts on whether ADHD persists into adulthood. Recognized as occurring in adults in 1978, it is currently not addressed separately from ADHD in childhood. Obstacles that clinicians face when assessing adults who may have ADHD include developmentally inappropriate diagnostic criteria, age-related changes, comorbidities and the possibility that high intelligence or situational factors can mask ADHD.

Cause

The specific causes of ADHD are not known.[45] There are, however, a number of factors that may contribute to, or exacerbate ADHD. They include genetics, diet and the social and physical environments.

Genetics

Twin studies indicate that the disorder is highly heritable and that genetics are a factor in about 75 percent of all cases.[24] Hyperactivity also seems to be primarily a genetic condition; however, other causes have been identified.[46]

Researchers believe that a large majority of ADHD cases arise from a combination of various genes, many of which affect dopamine transporters. Candidate genes include α2A adrenergic receptor, dopamine transporter, dopamine receptors D2/D3,[47] dopamine beta-hydroxylase monoamine oxidase A, catecholamine-methyl transferase, serotonin transporter promoter (SLC6A4), 5HT2A receptor, 5HT1B receptor,[48] the 10-repeat allele of the DAT1 gene,[49] the 7-repeat allele of the DRD4 gene,[49] and the dopamine beta hydroxylase gene (DBH TaqI).[50] A common variant of a gene called LPHN3 is estimated to be responsible for about 9% of the incidence of ADHD, and ADHD cases where this gene is present are particularly responsive to stimulant medication.[51]

Evolutionary theories

The hunter vs. farmer theory is a hypothesis proposed by author Thom Hartmann about the origins of ADHD. The theory proposes that hyperactivity may be an adaptive behavior in pre-modern humans[52] and that those with ADHD retain some of the older "hunter" characteristics associated with early pre-agricultural human society. According to this theory, individuals with ADHD may be more adept at searching and seeking and less adept at staying put and managing complex tasks over time.[53] Further evidence showing hyperactivity may be evolutionarily beneficial was put forth in 2006 in a study that found it may carry specific benefits for certain forms of society. In these societies, those with ADHD are hypothesized to have been more proficient in tasks involving risk or competition (i.e., hunting, mating rituals, etc.).[54] A genetic variant associated with ADHD (DRD4 48bp VNTR 7R allele), has been found to be at higher frequency in more nomadic populations and those with more of a history of migration.[55] Consistent with this, another group of researchers observed that the health status of nomadic Ariaal men was higher if they had the ADHD associated genetic variant (7R alleles). However in recently sedentary (non-nomadic) Ariaal those with 7R alleles seemed to have slightly worse health.[56]

Environmental

Twin studies to date have suggested that approximately 9 to 20 percent of the variance in hyperactive-impulsive-inattentive behavior or ADHD symptoms can be attributed to nonshared environmental (nongenetic) factors.[57][58][59][60] Environmental factors implicated include alcohol and tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy and environmental exposure to lead in very early life.[61] The relation of smoking to ADHD could be due to nicotine causing hypoxia (lack of oxygen) to the fetus in utero.[62] It could also be that women with ADHD are more likely to smoke[63] and therefore, due to the strong genetic component of ADHD, are more likely to have children with ADHD.[64] Complications during pregnancy and birth—including premature birth—might also play a role.[65] ADHD patients have been observed to have higher than average rates of head injuries;[66] however, current evidence does not indicate that head injuries are the cause of ADHD in the patients observed.[67] Infections during pregnancy, at birth, and in early childhood are linked to an increased risk of developing ADHD. These include various viruses (measles, varicella, rubella, enterovirus 71) and streptococcal bacterial infection.[68][69]

A 2007 study linked the organophosphate insecticide chlorpyrifos, which is used on some fruits and vegetables, with delays in learning rates, reduced physical coordination, and behavioral problems in children, especially ADHD.[70]

A 2010 study found that pesticide exposure is strongly associated with an increased risk of ADHD in children. Researchers analyzed the levels of organophosphate residues in the urine of more than 1,100 children aged 8 to 15 years old, and found that those with the highest levels of dialkyl phosphates, which are the breakdown products of organophosphate pesticides, also had the highest incidence of ADHD. Overall, they found a 35 percent increase in the odds of developing ADHD with every 10-fold increase in urinary concentration of the pesticide residues. The effect was seen even at the low end of exposure: children who had any detectable, above-average level of pesticide metabolite in their urine were twice as likely as those with undetectable levels to record symptoms of ADHD.[71][72]

Three government-funded longitudinal studies from 2010 and 2011 examined environmental exposure to organophosphate pesticides between pregnancy and grade school. Although the studies varied in techniques to measure pesticide exposure, they reached similar conclusions. Children exposed to higher levels of organophosphates during pregnancy were more likely to have lower IQs and problems focusing or solving problems. One study suggested that genetics play a strong role in whether exposure to organophosphates causes damage. Two studies found higher rates of ADHD diagnosis among children exposed to higher levels of organophosphate pesticides.[73]

Diet

A study[74] published in The Lancet in 2007 found a link between children’s ingestion of many commonly used artificial food colors, the preservative sodium benzoate and hyperactivity. In response to these findings, the British government took prompt action. According to the Food Standards Agency, the food regulatory agency in the UK, food manufacturers are being encouraged to voluntarily phase out the use of most artificial food colors by the end of 2009. Following the FSA’s actions, the European Commission ruled that any food products containing the “Southampton Six” (The contentious colourings are: sunset yellow FCF (E110), quinoline yellow (E104), carmoisine (E122), allura red (E129), tartrazine (E102) and ponceau 4R (E124)) must display warning labels on their packaging by 2010.[75] In the US, little has been done[clarification needed] to curb food manufacturer’s use of specific food colors, despite the new evidence presented by the Southampton study. However, the existing US Food Drug and Cosmetic Act[76] had already required that artificial food colors be approved for use, that they must be given FD&C numbers by the FDA, and the use of these colors must be indicated on the package.[77] This is why food packaging in the USA may state something like: "Contains FD&C Red #40." As of March 2011, the FDA was evaluating the scientific evidence of a link between dyes and ADHD; a preliminary analysis found there was no link.[78]

Social

The World Health Organization states that the diagnosis of ADHD can represent family dysfunction or inadequacies in the educational system rather than individual psychopathology.[79] Other researchers believe that relationships with caregivers have a profound effect on attentional and self-regulatory abilities. A study of foster children found that a high number of them had symptoms closely resembling ADHD.[80] Researchers have found behavior typical of ADHD in children who have suffered violence and emotional abuse.[24][81] Furthermore, Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder can result in attention problems that can look like ADHD.[82] ADHD is also considered to be related to sensory integration dysfunction.[83]

A 2010 article by CNN suggests that there is an increased risk for internationally adopted children to develop mental health disorders, such as ADHD and ODD.[84] The risk may be related to the length of time the children spent in an orphanage, especially if they were neglected or abused. Many of these families who adopted the affected children feel overwhelmed and frustrated, since managing their children may entail more responsibilities than originally anticipated. The adoption agencies may be aware of the child's behavioral history, but decide to withhold the information prior to the adoption. This in turn has resulted in some parents suing adoption agencies, in the abuse of children, and even in the relinquishment of the child.

Neurodiversity

Proponents of the neurodiversity theory assert that atypical (neurodivergent) neurological development is a normal human difference that is to be tolerated and respected just like any other human difference. Social critics argue that while biological factors may play a large role in difficulties with sitting still in class and/or concentrating on schoolwork in some children, these children could have failed to integrate others' social expectations of their behavior for a variety of other reasons.[85] As genetic research into ADHD proceeds, it may become possible to integrate this information with the neurobiology in order to distinguish disability from varieties of normal or even exceptional functioning in people along the same spectrum of attention differences.[86]

Social construct theory of ADHD

Social construction theory states that it is societies that determine where the line between normal and abnormal behavior is drawn. Thus society members including physicians, parents, teachers, and others are the ones who determine which diagnostic criteria are applied and, thus, determine the number of people affected.[87] This is exemplified in the fact that the DSM IV arrives at levels of ADHD three to four times higher than those obtained with use of the ICD 10.[13] Thomas Szasz, a proponent of this theory, has argued that ADHD was "invented and not discovered."[88][89]

Low arousal theory

According to the low arousal theory, people with ADHD need excessive activity as self-stimulation because of their state of abnormally low arousal.[90] The theory states that those with ADHD cannot self-moderate, and their attention can be gained only by means of environmental stimuli, which in turn results in disruption of attentional capacity and an increase in hyperactive behaviour.[91]

Without enough stimulation coming from the environment, an ADHD child will create it him or herself by walking around, fidgeting, talking, etc. This theory also explains why stimulant medications have high success rates and can induce a calming effect at therapeutic dosages among children with ADHD. It establishes a strong link with scientific data that ADHD is connected to abnormalities with the neurochemical dopamine and a powerful link with low-stimulation PET scan results in ADHD subjects.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of ADHD is unclear and there are a number of competing theories.[92] Research on children with ADHD has shown a general reduction of brain volume, but with a proportionally greater reduction in the volume of the left-sided prefrontal cortex. These findings suggest that the core ADHD features of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity may reflect frontal lobe dysfunction, but other brain regions in particular the cerebellum have also been implicated.[93] Neuroimaging studies in ADHD have not always given consistent results and as of 2008 are used only for research and not diagnostic purposes.[94] A 2005 review of published studies involving neuroimaging, neuropsychological genetics, and neurochemistry found converging lines of evidence to suggest that four connected frontostriatal regions play a role in the pathophysiology of ADHD: The lateral prefrontal cortex, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, caudate, and putamen.[95]

In one study a delay in development of certain brain structures by an average of three years occurred in ADHD elementary school aged patients. The delay was most prominent in the frontal cortex and temporal lobe, which are believed to be responsible for the ability to control and focus thinking. In contrast, the motor cortex in the ADHD patients was seen to mature faster than normal, suggesting that both slower development of behavioral control and advanced motor development might be required for the fidgetiness that characterizes ADHD.[96] It should be noted that stimulant medication itself may affect growth factors of the central nervous system.[97]

The same laboratory had previously found involvement of the "7-repeat" variant of the dopamine D4 receptor gene, which accounts for about 30 percent of the genetic risk for ADHD, in unusual thinness of the cortex of the right side of the brain; however, in contrast to other variants of the gene found in ADHD patients, the region normalized in thickness during the teen years in these children, coinciding with clinical improvement.[98]

In addition, SPECT scans found people with ADHD to have reduced blood circulation (indicating low neural activity),[99] and a significantly higher concentration of dopamine transporters in the striatum, which is in charge of planning ahead.[100][101] A study by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory in collaboration with Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York suggest that it is not the dopamine transporter levels that indicate ADHD, but the brain's ability to produce neurotransmitters like dopamine itself. The study was done by injecting 20 ADHD subjects and 25 control subjects with a radiotracer that attaches itself to dopamine transporters. The study found that it was not the transporter levels that indicated ADHD, but the dopamine itself. ADHD subjects showed lower levels of dopamine (hypodopaminergia) across the board. They speculated that since ADHD subjects had lower levels of dopamine to begin with, the number of transporters in the brain was not the telling factor. In support of this notion, plasma homovanillic acid, an index of dopamine levels, was found to be inversely related not only to childhood ADHD symptoms in adult psychiatric patients but to "childhood learning problems" in healthy subjects as well.[102] One interpretation of dopamine pathway tracers is that the biochemical "reward" mechanism works for those with ADHD only when the task performed is inherently motivating; low levels of dopamine raise the threshold at which someone can maintain focus on a task that is otherwise boring.[103] Neuroimaging studies also found that neurotransmitters level (e.g. dopamine and serotonin) in the synaptic cleft goes down during depression.[104][105]

A 1990 PET scan study by Alan J. Zametkin et al. found that global cerebral glucose metabolism was 8 percent lower in medication-naive adults who had been hyperactive since childhood.[106] Further studies found that chronic stimulant treatment had little effect on global glucose metabolism,[107] a 1993 study in girls failed to find a decreased global glucose metabolism, but found significant differences in glucose metabolism in 6 specific regions of the brains of ADHD girls as compared to control subjects. The study also found that differences in one specific region of the frontal lobe were statistically correlated with symptom severity.[108] A further study in 1997 also failed to find global differences in glucose metabolism, but, likewise, found differences in glucose normalization in specific regions of the brain. The 1997 study also noted that their findings were somewhat different than those in the 1993 study, and concluded that sexual maturation may have played a role in this discrepancy.[109] The significance of the research by Zametkin has not been determined and neither his group nor any other has been able to replicate the 1990 results.[110][111][112]

Critics, such as Jonathan Leo and David Cohen, who reject the characterization of ADHD as a disorder, contend that the controls for stimulant medication usage were inadequate in some lobar volumetric studies, which makes it impossible to determine whether ADHD itself or psychotropic medication used to treat ADHD is responsible for the decreased thickness observed[113] in certain brain regions. While the main study in question used age-matched controls, it did not provide information on height and weight of the subjects. These variables it has been argued could account for the regional brain size differences rather than ADHD itself.[114][115] They believe many neuroimaging studies are oversimplified in both popular and scientific discourse and given undue weight despite deficiencies in experimental methodology.[114][116]

Diagnosis

ADHD is diagnosed via a psychiatric assessment; to rule out other potential causes or comorbidities, physical examination, radiological imaging, and laboratory tests may be used.[117]

In North America, the DSM-IV criteria are often the basis for a diagnosis, while European countries usually use the ICD-10. If the DSM-IV criteria are used, rather than the ICD-10, a diagnosis of ADHD is 3–4 times more likely.[13] Factors other than those within the DSM or ICD however have been found to affect the diagnosis in clinical practice. A child's social and school environment as well as academic pressures at school are likely to be of influence.[118]

Many of the symptoms of ADHD occur from time to time in everyone; in patients with ADHD, the frequency of these symptoms is greater and patients' lives are significantly impaired. Impairment must occur in multiple settings to be classified as ADHD.[28] As with many other psychiatric and medical disorders, the formal diagnosis is made by a qualified professional in the field based on a set number of criteria. In the USA these criteria are laid down by the American Psychiatric Association in their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), 4th edition. Based on the DSM-IV criteria listed below, three types of ADHD are classified:

- ADHD, Combined Type: if both criteria 1A and 1B are met for the past 6 months

- ADHD Predominantly Inattentive Type: if criterion 1A is met but criterion 1B is not met for the past six months

- ADHD, Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Type: if criterion 1B is met but criterion 1A is not met for the past six months.[119]

The previously used term ADD expired with the most recent revision of the DSM. As a consequence, ADHD is the current nomenclature used to describe the disorder as one distinct disorder that can manifest itself as being a primary deficit resulting in hyperactivity/impulsivity (ADHD, predominately hyperactive-impulsive type) or inattention (ADHD, predominately inattentive type) or both (ADHD combined type).

DSM-IV

The diagnostic criteria outlined in DSM-IV assume that attention deficits (1) are a distinct, differentiated condition; (2) can be reliably measured using objective, behavioral measures; and (3)are abnormalities resulting from organic/biological origins.[120]

IA. Six or more of the following signs of inattention have been present for at least 6 months to a point that is disruptive and inappropriate for developmental level:

- Inattention:

- Often does not give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, work, or other activities.

- Often has trouble keeping attention on tasks or play activities.

- Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

- Often does not follow instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (not due to oppositional behavior or failure to understand instructions).

- Often has trouble organizing activities.

- Often avoids, dislikes, or does not want to do things that take a lot of mental effort for a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework).

- Often loses things needed for tasks and activities (such as toys, school assignments, pencils, books, or tools).

- Is often easily distracted.

- Often forgetful in daily activities.

IB. Six or more of the following signs of hyperactivity-impulsivity have been present for at least 6 months to an extent that is disruptive and inappropriate for developmental level:

- Hyperactivity:

- Often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat.

- Often gets up from seat when remaining in seat is expected.

- Often runs about or climbs when and where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may feel very restless).

- Often has trouble playing or enjoying leisure activities quietly.

- Is often "on the go" or often acts as if "driven by a motor".

- Often talks excessively.

- Impulsiveness:

- Often blurts out answers before questions have been finished.

- Often has trouble waiting one's turn.

- Often interrupts or intrudes on others (example: butts into conversations or games).

II. Some signs that cause impairment were present before age 7 years.

III. Some impairment from the signs is present in two or more settings (such as at school/work and at home).

IV. There must be clear evidence of significant impairment in social, school, or work functioning.

V. The signs do not happen only during the course of a Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Schizophrenia, or other Psychotic Disorder. The signs are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (such as Mood Disorder, Anxiety Disorder, Dissociative Identity Disorder, or a Personality Disorder).[121]

ICD-10

In the tenth edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) the signs of ADHD are given the name "Hyperkinetic disorders". When a conduct disorder (as defined by ICD-10[122]) is present, the condition is referred to as "Hyperkinetic conduct disorder". Otherwise the disorder is classified as "Disturbance of Activity and Attention", "Other Hyperkinetic Disorders" or "Hyperkinetic Disorders, Unspecified". The latter is sometimes referred to as, "Hyperkinetic Syndrome".[122]

Other guidelines

The American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline for children with ADHD emphasizes that a reliable diagnosis is dependent upon the fulfillment of three criteria:[123]

- The use of explicit criteria for the diagnosis using the DSM-IV-TR.

- The importance of obtaining information about the child’s signs in more than one setting.

- The search for coexisting conditions that may make the diagnosis more difficult or complicate treatment planning.

All three criteria are determined using the patient's history given by the parents, teachers and/or the patient.

Adults often continue to be impaired by ADHD. Adults with ADHD are diagnosed under the same criteria, including the stipulation that their signs must have been present prior to the age of seven.[124] Adults face some of their greatest challenges in the areas of self-control and self-motivation, as well as executive functioning, usually having more signs of inattention and fewer of hyperactivity or impulsiveness than children do.[125]

The American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) considers it necessary that the following be present before attaching the label of ADHD to a child:

- The behaviors must appear before age 7.

- They must continue for at least six months.

- The symptoms must also create a real handicap in at least two of the following areas of the child’s life:

- in the classroom,

- on the playground,

- at home,

- in the community, or

- in social settings.[126]

If a child seems too active on the playground but not elsewhere, the problem might not be ADHD. It might also not be ADHD if the behaviors occur in the classroom but nowhere else. A child who shows some symptoms would not be diagnosed with ADHD if his or her schoolwork or friendships are not impaired by the behaviors.[126]

Differential

To make the diagnosis of ADHD, a number of other possible medical and psychological conditions must be excluded.

Medical conditions

Medical conditions that must be excluded include: hypothyroidism, anemia, lead poisoning, chronic illness, hearing or vision impairment, substance abuse, medication side-effects, sleep impairment and child abuse,[127] and cluttering (tachyphemia) among others.

Sleep conditions

As with other psychological and neurological issues, the relationship between ADHD and sleep is complex. In addition to clinical observations, there is substantial empirical evidence from a neuroanatomic standpoint to suggest that there is considerable overlap in the central nervous system centers that regulate sleep and those that regulate attention/arousal.[128] Primary sleep disorders play a role in the clinical presentation of symptoms of inattention and behavioral dysregulation. There are multilevel and bidirectional relationships among sleep, neurobehavioral functioning and the clinical syndrome of ADHD.[129]

Behavioral manifestations of sleepiness in children range from the classic ones (yawning, rubbing eyes), to externalizing behaviors (impulsivity, hyperactivity, aggressiveness), to mood lability and inattentiveness.[128][130][131] Many sleep disorders are important causes of symptoms that may overlap with the cardinal symptoms of ADHD; children with ADHD should be regularly and systematically assessed for sleep problems.[128][132]

From a clinical standpoint, mechanisms that account for the phenomenon of excessive daytime sleepiness include:

- Chronic sleep deprivation, that is insufficient sleep for physiologic sleep needs,

- Fragmented or disrupted sleep, caused by, for example, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) or periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD),

- Primary clinical disorders of excessive daytime sleepiness, such as narcolepsy and

- Circadian rhythm disorders, such as delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS). A study in the Netherlands compared two groups of unmedicated 6-12-year-olds, all of them with "rigorously diagnosed ADHD". 87 of them had problems getting to sleep, 33 had no sleep problems. The larger group had a significantly later dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) than did the children with no sleep problems.[133]

Management

Methods of treatment often involve some combination of behavior modification, life-style changes, counseling, and medication. A 2005 study found that medical management and behavioral treatment is the most effective ADHD management strategy, followed by medication alone, and then behavioral treatment.[134] While medication has been shown to improve behavior when taken over the short term, they have not been shown to alter long-term outcomes.[135] Medications have at least some effect in about 80% of people.[136]

Psychosocial

The evidence is strong for the effectiveness of behavioral treatments in ADHD.[137] It is recommended first line in those who have mild symptoms and in preschool aged children.[138] Psychological therapies used include psychoeducational input, behavior therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), family therapy, school-based interventions, social skills training, parent management training,[24] neurofeedback,[139] and nature exposure.[140][141] Parent training and education have been found to have short-term benefits.[142] There is a deficiency of good research on the effectiveness of family therapy for ADHD, but the evidence that exists shows that it is comparable in effectiveness to treatment as usual in the community and is superior to medication placebo.[143] Several ADHD specific support groups exist as informational sources and to help families cope with challenges associated with dealing with ADHD.

Medication

Stimulant medications are the medical treatment of choice.[144] There are a number of non-stimulant medications, such as atomoxetine, that may be used as alternatives.[144] There are no good studies of comparative effectiveness between various medications, and there is a lack of evidence on their effects on academic performance and social behaviors.[145] While stimulants and atomoxetine are generally safe, there are side-effects and contraindications to their use.[144] Medications are not recommended for preschool children, as their long-term effects in such young people are unknown.[24][146] There is very little data on the long-term benefits or adverse effects of stimulants for ADHD.[147] Any drug used for ADHD may have adverse drug reactions such as psychosis and mania,[148] though methylphenidate-induced psychosis is uncommon.[149] People with ADHD have an increased risk of substance abuse, and stimulant medications reduce this risk.[150][151] Stimulant medications in and of themselves however have the potential for abuse and dependence.[152] Guidelines on when to use medications vary internationally, with the UK's National Institute of Clinical Excellence, for example, recommending use only in severe cases, while most United States guidelines recommend medications in nearly all cases.[153]

Prognosis

Children diagnosed with ADHD have significant difficulties in adolescence, regardless of treatment.[154][155] In the United States, 37 percent of those with ADHD do not get a high school diploma even though many of them will receive special education services.[156] A 1995 briefing citing a 1994 book review says the combined outcomes of the expulsion and dropout rates indicate that almost half of all ADHD students never finish high school.[157] Also in the US, less than 5 percent of individuals with ADHD get a college degree[158] compared to 28 percent of the general population.[159] Those with ADHD as children are at increased risk of a number of adverse life outcomes once they become teenagers. These include a greater risk of auto crashes, injury and higher medical expenses, earlier sexual activity, and teen pregnancy.[160] Russell Barkley states that adult ADHD impairments affect "education, occupation, social relationships, sexual activities, dating and marriage, parenting and offspring psychological morbidity, crime and drug abuse, health and related lifestyles, financial management, or driving. ADHD can be found to produce diverse and serious impairments".[161] The proportion of children meeting the diagnostic criteria for ADHD drops by about 50 percent over three years after the diagnosis. This occurs regardless of the treatments used and also occurs in untreated children with ADHD.[127][162][163] ADHD persists into adulthood in about 30 to 50 percent of cases.[7] Those affected are likely to develop coping mechanisms as they mature, thus compensating for their previous ADHD.[9]

Epidemiology

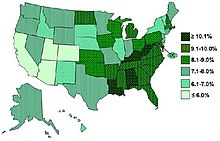

ADHD's global prevalence is estimated at 3 to 5 percent in people under the age of 19. There is, however, both geographical and local variability among studies. Children in North America appear to have a higher rate of ADHD than children in Africa and the Middle East.[165] Published studies have found rates of ADHD as low as 2 percent and as high as 14 percent among school aged children.[166] The rates of diagnosis and treatment of ADHD are also much higher on the East Coast of the USA than on the West Coast.[167] The frequency of the diagnosis differs between male children (10%) and female children (4%) in the United States.[168] This difference between genders may reflect either a difference in susceptibility or that females with ADHD are less likely to be diagnosed than males.[169]

Rates of ADHD diagnosis and treatment have increased in both the UK and the USA since the 1970s. In the UK an estimated 0.5 per 1,000 children had ADHD in the 1970s, while 3 per 1,000 received ADHD medications in the late 1990s. In the USA in the 1970s 12 per 1,000 children had the diagnosis, while in the late 1990s 34 per 1,000 had the diagnosis and the numbers continue to increase.[24]

In the UK in 2003 a prevalence of 3.6 percent is reported in male children and less than 1 percent is reported in female children.[170]

History

Hyperactivity has long been part of the human condition. Sir Alexander Crichton describes "mental restlessness" in his book An Inquiry Into the Nature and Origin of Mental Derangement written in 1798.[171][172] The terminology used to describe the symptoms of ADHD has gone through many changes over history including: "minimal brain damage", "minimal brain dysfunction" (or disorder),[173] "learning/behavioral disabilities" and "hyperactivity". In the DSM-II (1968) it was the "Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood". In the DSM-III "ADD (Attention-Deficit Disorder) with or without hyperactivity" was introduced. In 1987 this was changed to ADHD in the DSM-III-R and subsequent editions.[174] The use of stimulants to treat ADHD was first described in 1937.[175]

Society and culture

The media have reported on many issues related to ADHD. In 2001 PBS's Frontline aired a one-hour program about the effects of the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in minors, entitled "Medicating Kids."[176] The program included a selection of interviews with representatives of various points of view. In one segment, entitled Backlash, retired neurologist Fred Baughman and Peter Breggin whom PBS described as "outspoken critics who insist [ADHD is] a fraud perpetrated by the psychiatric and pharmaceutical industries on families anxious to understand their children's behavior"[177] were interviewed on the legitimacy of the disorder. Russell Barkley and Xavier Castellanos, then head of ADHD research at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), defended the viability of the disorder. In the interview with Castellanos, he stated that little is scientifically understood.[178] Lawrence Diller was interviewed on the business of ADHD along with a representative from Shire Plc (then known as Shire-Richwood).[citation needed]

A number of notable individuals have given controversial opinions on ADHD. Scientologist Tom Cruise's interview with Matt Lauer was widely watched by the public in 2005. In this interview he spoke about postpartum depression and also referred to Ritalin and Adderall as being "street drugs" rather than as ADHD medication.[179] In England Baroness Susan Greenfield, a leading neuroscientist, spoke out publicly in 2007 in the House of Lords about the need for a wide-ranging inquiry into the dramatic increase in the diagnosis of ADHD in the UK and possible causes following a BBC Panorama programme that highlighted US research (The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD by the University of Buffalo) suggesting drugs are no better than other forms of therapy for ADHD in the long term.[180] However, in 2010 the BBC Trust criticized the 2007 BBC Panorama programme for summarizing the US research as showing "no demonstrable improvement in children's behaviour after staying on ADHD medication for three years" when in actuality "the study found that medication did offer a significant improvement over time."[181]

Neil Bush (brother of former President George W. Bush) is credited in the cast of a 2005 ADHD documentary called The Drugging of Our Children[182] directed by Gary Null. In the film's trailer[183] Bush says: "Just because it is easy to drug a kid and get them to be compliant doesn't make it right to do it".

As of 2009[update], eight percent of all Major League Baseball players have been diagnosed with ADHD, making the disorder epidemic among this population. The increase coincided with the League's 2006 ban on stimulants (q.v. Major League Baseball drug policy).[184]

Legal status of medications

Stimulants legal status was recently reviewed by several international organizations:

- Internationally, methylphenidate is a Schedule II drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[185]

- In the United States, methylphenidate is classified as a Schedule II controlled substance, the designation used for substances that have a recognized medical value but present a high likelihood for abuse because of their addictive potential.

- In the United Kingdom, methylphenidate is a controlled 'Class B' substance, and possession without prescription is illegal, with a sentence up to 14 years and/or an unlimited fine.[186]

- In New Zealand, it is a 'class B2 controlled substance'. unlawful possession is punishable by 6-month prison sentence and distribution of it is punishable by a 14-year sentence.

Controversies

ADHD and its diagnosis and treatment have been considered controversial since the 1970s.[16][18][187] The controversies have involved clinicians, teachers, policymakers, parents and the media. Opinions regarding ADHD range from not believing it exists at all[17] to believing there are genetic and physiological bases for the condition as well as disagreement about the use of stimulant medications in treatment.[17][18][19] Some sociologists consider ADHD to be a "classic example of the medicalization of deviant behavior, defining a previously nonmedical problem as a medical one".[16] Most healthcare providers in U.S. accept that ADHD is a genuine disorder with debate in centering mainly around how it is diagnosed and treated.[20][21][22] However, The British Psychological Society said in a 1997 report that physicians and psychiatrists should not follow the American example of applying medical labels to such a wide variety of attention-related disorders: "The idea that children who don’t attend or who don’t sit still in school have a mental disorder is not entertained by most British clinicians."[188][189] In 2009, the British Psychological Society, in collaboration with the Royal College of Psychiatrists, released a set of guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD.[190] In its guideline, it state that available evidence indicate that ADHD is a valid diagnosis. However, it states that the diagnosis lack any biological basis and that "[c]ontroversial issues surround changing thresholds applied to the definition of illness as new knowledge and treatments are developed and the extent to which it is acknowledged that clinical thresholds are socially and culturally influenced and determine how an individual's level of functioning within the 'normal cultural environment' is assessed". It further states that "the acceptable thresholds for impairment are partly driven by the contemporary societal view of what is an acceptable level of deviation from the norm."

Others have included that it may stem from a misunderstanding of the diagnostic criteria and how they are utilized by clinicians,[15]: p.3 teachers, policymakers, parents and the media.[17] Debates center around key controversial issues; whether ADHD is a disability or merely a neurological description, the cause of the disorder, the changing of the diagnostic criteria, the rapid increase in diagnosis of ADHD, and the use of stimulants to treat the disorder.[191] Possible long-term side-effects of stimulants and their usefulness are largely unknown because of a lack of long-term studies.[192] Some research raises questions about the long-term effectiveness and side-effects of medications used to treat ADHD.[193]

In 1998, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) released a consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD. The statement, while recognizing that stimulant treatment is controversial, supports the validity of the ADHD diagnosis and the efficacy of stimulant treatment. It found controversy only in the lack of sufficient data on long-term use of medications, and in the need for more research in many areas.[194]

With a "wide variation in diagnosis across states, races, and ethnicities"[195] some investigators [who?] suspect that factors other than neurological conditions play a role when the diagnosis of ADHD is made.[195][196] Two studies published in 2010 suggest that the diagnosis is more likely to be made in the younger children within a grade; the authors propose that such a misdiagnosis of ADHD within a grade may be due to different states of maturity and may lead to potentially inappropriate treatment.[195][196] A further study involving a million children in British Columbia (Canada) published in 2012 using data from 1997 to 2008 unambiguously confirmed the phenomenom, finding children born in December (the youngest) 39% more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than those born in January (the oldest).[197]

References

- ^ Zwi M, Ramchandani P, Joughin C (2000). "Evidence and belief in ADHD". BMJ. 321 (7267): 975–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7267.975. PMC 1118810. PMID 11039942.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Biederman J (1998). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a life-span perspective". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 59 Suppl 7: 4–16. PMID 9680048.

- ^ "NIMH • ADHD • Complete Publication". Archived from the original on 2007-10-18.

- ^ Nair J, Ehimare U, Beitman BD, Nair SS, Lavin A (2006). "Clinical review: evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in children". Mo Med. 103 (6): 617–21. PMID 17256270.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rader R, McCauley L, Callen EC (2009). "Current strategies in the diagnosis and treatment of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Am Fam Physician. 79 (8): 657–65. PMID 19405409.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van Cleave J, Leslie LK (2008). "Approaching ADHD as a chronic condition: implications for long-term adherence". Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 46 (8): 28–37. PMID 18777966.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bálint S, Czobor P, Mészáros A, Simon V, Bitter I (2008). "[Neuropsychological impairments in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a literature review]". Psychiatr Hung (in Hungarian). 23 (5): 324–35. PMID 19129549.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Elia J, Ambrosini PJ, Rapoport JL (1999). "Treatment of attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder". The New England Journal of Medicine. 340 (10): 780–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM199903113401007. PMID 10072414.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gentile, Julie; Atiq, R; Gillig, PM (2004). "Adult ADHD: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis and Medication Management". Psychiatry. 3 (8): 24–30. PMC 2957278. PMID 20963192.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|month=(help) - ^ Barkley, Russell A. (2007). "ADHD in Adults: History, Diagnosis, and Impairments". ContinuingEdCourses.net. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M; et al. (2005). "The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population". Psychological medicine. 35 (2): 245–56. doi:10.1017/S0033291704002892. PMID 15841682.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dulcan M (1997). "Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 36 (10 Suppl): 85S–121S. doi:10.1097/00004583-199710001-00007. PMID 9334567.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Singh I (2008). "Beyond polemics: science and ethics of ADHD". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 9 (12): 957–64. doi:10.1038/nrn2514. PMID 19020513.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sciutto M.J., Nolfi C.J., Bluhm C. (2004). "Effects of Child Gender and Symptom Type on Referrals for ADHD by Elementary School Teachers". Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 12 (4): 247–253. doi:10.1177/10634266040120040501.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Ramsay, J. Russell. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adult ADHD. Routledge, 2007. ISBN 0-415-95501-7

- ^ a b c Parrillo, Vincent (2008). Encyclopedia of Social Problems. SAGE. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4129-4165-5. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- ^ a b c d "Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder". US department of health and human services. 1999. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Mayes R, Bagwell C, Erkulwater J (2008). "ADHD and the rise in stimulant use among children". Harv Rev Psychiatry. 16 (3): 151–66. doi:10.1080/10673220802167782. PMID 18569037.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Cohen, Donald J.; Cicchetti, Dante (2006). Developmental psychopathology. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-23737-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Sim MG, Hulse G, Khong E (2004). "When the child with ADHD grows up" (PDF). Aust Fam Physician. 33 (8): 615–8. PMID 15373378.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Silver, Larry B. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 3 edition (September 2003) ISBN 1-58562-131-5; Online July 20, 2009

- ^ a b Schonwald A, Lechner E (2006). "Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: complexities and controversies". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 18 (2): 189–95. doi:10.1097/01.mop.0000193302.70882.70. PMID 16601502.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Goldman LS, Genel M, Bezman RJ, Slanetz PJ (1998). "Diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association". JAMA. 279 (14): 1100–7. doi:10.1001/jama.279.14.1100. PMID 9546570.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g "CG72 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): full guideline" (PDF). NHS. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ "Brain Matures A Few Years Late In ADHD, But Follows Normal Pattern". Sciencedaily.com. 2007-11-13. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ^ Wiener, Jerry M., Editor (2003). Textbook Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 1-58562-057-2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DSM-IV-TR workgroup. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- ^ a b Google Health - Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- ^ a b c "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)." Health & Outreach. Publications. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder/complete-index.shtml July 15, 2009

- ^ Brewis, Alexandra; Schmidt, Karen L.; Meyer, Mary (2000-12). "ADHD-Type Behavior and Harmful Dysfunction in Childhood: A Cross-Cultural Model". American Anthropologist. 102 (4): 826. doi:10.1525/aa.2000.102.4.823.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Rapport MD, Bolden J, Kofler MJ, Sarver DE, Raiker JS, Alderson RM (2009). "Hyperactivity in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a ubiquitous core symptom or manifestation of working memory deficits?". J Abnorm Child Psychol. 37 (4): 521–34. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9287-8. PMID 19083090.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ University of Central Florida (2009-03-09). "UCF study: Hyperactivity enables children with ADHD to stay alert". Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ Shreeram S, He JP, Kalaydjian A, Brothers S, Merikangas KR (2009). "Prevalence of enuresis and its association with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among U.S. children: results from a nationally representative study". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 48 (1): 35–41. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e318190045c. PMC 2794242. PMID 19096296.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hagberg BS, Miniscalco C, Gillberg C (2010). "Clinic attenders with autism or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: cognitive profile at school age and its relationship to preschool indicators of language delay". Res Dev Disabil. 31 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2009.07.012. PMID 19713073.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brunsvold GL, Oepen G (2008). "Comorbid Depression in ADHD: Children and Adolescents". Psychiatric Times. 25 (10).

- ^ a b c d Krull, K.R. (December 5, 2007). "Evaluation and diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children" (Subscription required). Uptodate. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ Hofvander B, Ossowski D, Lundström S, Anckarsäter H (2009). "Continuity of aggressive antisocial behavior from childhood to adulthood: The question of phenotype definition". Int J Law Psychiatry. 32 (4): 224–34. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.04.004. PMID 19428109.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Philipsen A (2006). "Differential diagnosis and comorbidity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) in adults". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 256 Suppl 1: i42–6. doi:10.1007/s00406-006-1006-2. PMID 16977551.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bauermeister, J., Shrout, P., Chávez, L., Rubio-Stipec, M., Ramírez, R., Padilla, L., et al. (2007, August). ADHD and gender: are risks and sequela of ADHD the same for boys and girls?. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 48(8), 831-839. Retrieved February 17, 2009, doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01750.x

- ^ Bauermeister J., Shrout P., Chávez L., Rubio-Stipec M., Ramírez R., Padilla L.; et al. (2007). "ADHD and gender: are risks and sequela of ADHD the same for boys and girls?". Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 48 (8): 831–839. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01750.x. PMID 17683455.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b ADHD in Adults: Symptoms, Statistics, Causes, Types, Treatments, and More

- ^ a b Tom, Catherine M. (2005-01-15). "Recognizing and Treating ADHD in Adolescents and Adults". uspharmacist.com. Archived from the original on 2008-02-05. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Gentile, Julie; Atiq, R; Gillig, PM (2006). "Adult ADHD: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Medication Management". Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township)). 3 (8). Psychiatrymmc.com: 25–30. PMC 2957278. PMID 20963192.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bailly, Lionel (2005). "Stimulant medication for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: evidence-b(i)ased practice?" (Full text). Psychiatric Bulletin. 29 (8). The Royal College of Psychiatrists: 284–287. doi:10.1192/pb.29.8.284.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Barkley, Russel A. "Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Nature, Course, Outcomes, and Comorbidity". Retrieved 2006-06-26.

- ^ Volkow, ND; Wang, GJ; Kollins, SH; Wigal, TL; Newcorn, JH; Telang, F; Fowler, JS; Zhu, W; Logan, J (2009). "Evaluating Dopamine Reward Pathway in ADHD". JAMA. 302 (10): 1084–1091. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1308. PMC 2958516. PMID 19738093.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author=and|last1=specified (help) - ^ Roman T, Rohde LA, Hutz MH (2004). "Polymorphisms of the dopamine transporter gene: influence on response to methylphenidate in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder". American Journal of Pharmacogenomics. 4 (2): 83–92. doi:10.2165/00129785-200404020-00003. PMID 15059031.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Swanson JM, Flodman P, Kennedy J; et al. (2000). "Dopamine Genes and ADHD". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 24 (1): 21–5. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(99)00062-7. PMID 10654656.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith KM, Daly M, Fischer M; et al. (2003). "Association of the dopamine beta hydroxylase gene with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: genetic analysis of the Milwaukee longitudinal study". Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 119 (1): 77–85. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.20005. PMID 12707943.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arcos-Burgos M, et al. "A common variant of the latrophilin 3 gene, LPHN3, confers susceptibility to ADHD and predicts effectiveness of stimulant medication." Mol Psychiatry. 2010 Nov;15(11):1053-66. Epub 2010 Feb 16. [2]

- ^ Arcos-Burgos M, Acosta MT (2007). "Tuning major gene variants conditioning human behavior: the anachronism of ADHD". Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17 (3): 234–8. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2007.04.011. PMID 17467976.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hartmann, Thom (2003). The Edison gene: ADHD and the gift of the hunter child. Rochester, Vt: Park Street Press. ISBN 0-89281-128-5.

- ^ Williams J, Taylor E (2006). "The evolution of hyperactivity, impulsivity and cognitive diversity". J R Soc Interface. 3 (8): 399–413. doi:10.1098/rsif.2005.0102. PMC 1578754. PMID 16849269.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chen CS, Burton M, Greenberger E, Dmitrieva J (1999). "Population migration and the variation of dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) allele frequencies around the globe". Evolution and Human Behavior. 20 (5): 309–324. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(99)00015-X.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eisenberg DT, Campbell B, Gray PB, Sorenson MD (2008). "Dopamine receptor genetic polymorphisms and body composition in undernourished pastoralists: an exploration of nutrition indices among nomadic and recently settled Ariaal men of northern Kenya". BMC Evol. Biol. 8: 173. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-173. PMC 2440754. PMID 18544160.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Levy et al., 1997[verification needed]

- ^ Nigg, 2006[verification needed]

- ^ Sherman, Silberg et al., 1996[verification needed]

- ^ Sherman DK, Iacono WG, McGue MK (1997). "Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder dimensions: a twin study of inattention and impulsivity-hyperactivity". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 36 (6): 745–53. doi:10.1097/00004583-199706000-00010. PMID 9183128.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Braun JM, Kahn RS, Froehlich T, Auinger P, Lanphear BP (2006). "Exposures to environmental toxicants and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in U.S. children". Environ. Health Perspect. 114 (12): 1904–9. doi:10.1289/ehp.10274. PMC 1764142. PMID 17185283.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bad behaviour 'linked to smoking'". BBC. 31 July 2005. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ "Ability To Quit Smoking May Depend On ADHD Symptoms, Researchers Find". Science Daily. 24 November 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ "Prenatal Smoking Increases ADHD Risk In Some Children". Science Daily. 11 April 2007. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ "ADHD 'linked to premature birth'". BBC. 4 June 2006. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ Keenan HT, Hall GC, Marshall SW (2008). "Early head injury and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: retrospective cohort study;". BMJ. 337: a1984. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1984. PMC 2590885. PMID 18988644.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mental Health: A report of the surgeon general". 1999. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- ^ Millichap JG (2008). "Etiologic classification of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Pediatrics. 121 (2): e358–65. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1332. PMID 18245408.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Millichap JG. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician’s Guide to ADHD. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2010

- ^ Study Links Organophosphate Insecticide Used on Corn With ADHD. Beyond Pesticides. 5 January 2007.

- ^ Klein, Sarah. Study: ADHD linked to pesticide exposure. CNN. 17 May 2010.

- ^ Maugh II, Thomas H. (2010-05-16). "Study links pesticide to ADHD in children". The Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Pesticide Exposure in Womb Linked to Lower IQ

- ^ McCann D, Barrett A, Cooper A (2007). "Food additives and hyperactive behaviour in 3-year-old and 8/9-year-old children in the community: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial". Lancet. 370 (9598): 1560–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61306-3. PMID 17825405.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ministers on board with 'Southampton six' phase-out".

- ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- ^ "FDA Probes Link Between Food Dyes, Kids' Behavior". Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ^ "www.euro.who.int" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ Template:PDFlink

- ^ Adam James (2004) Clinical psychology publishes critique of ADHD diagnosis and use of medication on children published on Psychminded.co.uk Psychminded Ltd

- ^ Cuffe, S.P.; McCullough, Elizabeth L.; Pumariega, Andres J. (1994). "Comorbidity of attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder". Journal of Child and Family Studies. 3 (3): 327–336. doi:10.1007/BF02234689.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Sensory integration disorder". healthatoz.com. 2006-08-14. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ Park, Madison (14 April 2010). / "Adopted children at greater risk for mental health disorders". CNN.com. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Rethinking ADHD[dead link]

- ^ Susan Smalley (2008). "Reframing ADHD in the Genomic Era". Psychiatric Times. 25 (7).

- ^ Parens E, Johnston J (2009). "Facts, values, and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): an update on the controversies". Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 3 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-3-1. PMC 2637252. PMID 19152690.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Chriss, James J. (2007). Social control: an introduction. Cambridge, UK: Polity. p. 230. ISBN 0-7456-3858-9.

- ^ Szasz, Thomas Stephen (2001). Pharmacracy: medicine and politics in America. New York: Praeger. p. 212. ISBN 0-275-97196-1.

- ^ "ADHD". Sci.csuhayward.edu. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ^ Sikström S, Söderlund G (2007). "Stimulus-dependent dopamine release in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Psychol Rev. 114 (4): 1047–75. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.1047. PMID 17907872.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Evaluation and diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children". December 5, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- ^ Krain, Amy; Castellanos, FX (2006). "Brain development and ADHD". Clinical Psychology Review. 26 (4): 433–444. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.005. PMID 16480802.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help) - ^ "MerckMedicus Modules: ADHD - Pathophysiology". August 2002. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010.

- ^ Bush G, Valera EM, Seidman LJ (2005). "Functional neuroimaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review and suggested future directions". Biological Psychiatry. 57 (11): 1273–84. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.034. PMID 15949999.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brain Matures a Few Years Late in ADHD, But Follows Normal Pattern NIMH Press Release, November 12, 2007

- ^ Joshi SV; Adam, H. M. (2002). "ADHD, growth deficits, and relationships to psychostimulant use". Pediatrics in Review. 23 (2): 67–8, discussion 67–8. doi:10.1542/pir.23-2-67. PMID 11826259.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gene Predicts Better Outcome as Cortex Normalizes in Teens with ADHD NIMH Press Release, August 6, 2007

- ^ Lou HC, Andresen J, Steinberg B, McLaughlin T, Friberg L (1998). "The striatum in a putative cerebral network activated by verbal awareness in normals and in ADHD children". Eur J Neurol. 5 (1): 67–74. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.1998.510067.x. PMID 10210814.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dougherty DD, Bonab AA, Spencer TJ, Rauch SL, Madras BK, Fischman AJ (1999). "Dopamine transporter density in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Lancet. 354 (9196): 2132––33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04030-1. PMID 10609822.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dresel SH, Kung MP, Plössl K, Meegalla SK, Kung HF (1998). "Pharmacological effects of dopaminergic drugs on in vivo binding of [99mTc]TRODAT-1 to the central dopamine transporters in rats". European journal of nuclear medicine. 25 (1): 31–9. PMID 9396872.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Coccaro EF, Hirsch SL, Stein MA (2007). "Plasma homovanillic acid correlates inversely with history of learning problems in healthy volunteer and personality disordered subjects". Psychiatry research. 149 (1–3): 297–302. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.009. PMID 17113158.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Identifying Brain Differences In People With ADHD : NPR

- ^ "The Role of Dopamine and Norepinephrine in Depression".

- ^ "The Chemistry of Depression".

- ^ Zametkin AJ, Nordahl TE, Gross M (1990). "Cerebral glucose metabolism in adults with hyperactivity of childhood onset". N. Engl. J. Med. 323 (20): 1361–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM199011153232001. PMID 2233902.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Matochik JA, Liebenauer LL, King AC, Szymanski HV, Cohen RM, Zametkin AJ (1994). "Cerebral glucose metabolism in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder after chronic stimulant treatment". Am J Psychiatry. 151 (5): 658–64. PMID 8166305.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zametkin AJ, Liebenauer LL, Fitzgerald GA (1993). "Brain metabolism in teenagers with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 50 (5): 333–40. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820170011002. PMID 8489322.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ernst M, Cohen RM, Liebenauer LL, Jons PH, Zametkin AJ (1997). "Cerebral glucose metabolism in adolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 36 (10): 1399–406. doi:10.1097/00004583-199710000-00022. PMID 9334553.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Armstrong, Thomas (1999). Add/Adhd Alternatives in the Classroom. ASCD. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-87120-359-5. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ernst M, Liebenauer LL, King AC, Fitzgerald GA, Cohen RM, Zametkin AJ (1994). "Reduced brain metabolism in hyperactive girls". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 33 (6): 858–68. doi:10.1097/00004583-199407000-00012. PMID 8083143.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Díaz-Heijtz R, Mulas F, Forssberg H (2006). "[Alterations in the pattern of dopaminergic markers in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder]". Revista De Neurologia (in Spanish). 42 Suppl 2: S19–23. PMID 16555214.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Philip Shaw, MD; Jason Lerch, PhD; Deanna Greenstein, PhD; Wendy Sharp, MSW; Liv Clasen, PhD; Alan Evans, PhD; Jay Giedd, MD; F. Xavier Castellanos, MD; Judith Rapoport, MD (2006). "Longitudinal Mapping of Cortical Thickness and Clinical Outcome in Children and Adolescents With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 5 (63): 540–549. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.540. PMID 16651511.

- ^ a b David Cohen (2004). "An Update on ADHD Neuroimaging Research" (PDF). The Journal of Mind and Behavior. 25 (2). The Institute of Mind and Behavior, Inc: 161–166. ISSN 0271–0137. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ David Cohen (2003). "Broken brains or flawed studies? A critical review of ADHD neuroimaging studies". The Journal of Mind and Behavior. 24: 29–56.

- ^ Jessica Andersson (2011). "Biochemical changes linked to ADHD". All About ADHD. 1: 25–32.

- ^ Joughin C, Ramchandani P, Zwi M (2003). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". American Family Physician. 67 (9): 1969–70. PMID 12751659.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schneider H, Eisenberg D (2006). "Who receives a diagnosis of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in the United States elementary school population?". Pediatrics. 117 (4): e601–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1308. PMID 16585277.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Adults with ADHD, adults with ADD

- ^ Oliverio, Annamarie. & Lauderdale, Pat. Therapeutic states and attention deficits: differential cross-national diagnostics and treatments. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 1996;10(2):355-373.

- ^ "Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Information Sheet". PsychNet-UK. Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ a b ICD Version 2006: F91. World Health Organization. Retrieved on December 11, 2006.

- ^ American Academy of Pediatrics. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Committee on Quality Improvement (2001). "Clinical practice guideline: treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Pediatrics. 108 (4): 1033–44. doi:10.1542/peds.108.4.1033. PMID 11581465.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "PsychiatryOnline".

- ^ Medscape.com (subscription required)

- ^ a b American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry. "ADHD - A Guide for Families." June 27, 2009. http://www.aacap.org/cs/adhd_a_guide_for_families/what_is_adhd

- ^ a b Smucker WD, Hedayat M (2001). "Evaluation and treatment of ADHD". American Family Physician. 64 (5): 817–29. PMID 11563573.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Owens JA (2005). "The ADHD and sleep conundrum: a review". Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 26 (4): 312–22. doi:10.1097/00004703-200508000-00011. PMID 16100507.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Owens JA (2008). "Sleep disorders and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Current Psychiatry Reports. 10 (5): 439–44. doi:10.1007/s11920-008-0070-x. PMID 18803919.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Golan N, Shahar E, Ravid S, Pillar G (2004). "Sleep disorders and daytime sleepiness in children with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder". Sleep. 27 (2): 261–6. PMID 15124720.