Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Paul Leroy Robeson |

| Born | April 9, 1898 Princeton, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | January 23, 1976 (aged 77) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Genres | Spirituals International folk Musicals |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, concert singer, athlete, lawyer, social activist |

| Instrument | Vocals |

| Years active | 1917–63 |

| Personal information | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born: | April 9, 1898 | ||||||||

| Career information | |||||||||

| College: | Rutgers | ||||||||

| Position: | End | ||||||||

| Career history | |||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||||

| First team All-American (1917, 1918) | |||||||||

| Career NFL statistics as of 1922 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

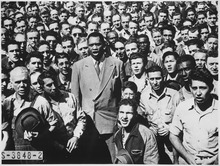

Paul Leroy Robeson (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈroʊbsən/ ROHB-sən April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American singer and actor who was a political activist for the Civil Rights Movement. Robeson's knowledge of his father's experiences as a slave, and Robeson's belief that social injustices were extant in the world effectuated in him becoming politically outspoken. His advocacy of anti-imperialism, his affiliation with Communism, and his criticism of the US brought retribution from the US government and public condemnation in the US. He was blacklisted, and to his financial and social detriment, he refused to rescind his stand on his beliefs and remained opposed to the direction of US policies. He retired privately and remained recalcitrant to the policies of the U.S. government.

Robeson won a scholarship to Rutgers University, where he became a football All-American and the class valedictorian. After Rutgers, he attended Columbia Law School, while playing in the National Football League (NFL). At Columbia, he sang and acted in off-campus productions prior to graduating in 1923. Post-graduate, he gave theatrical performances in The Emperor Jones and All God's Chillun Got Wings, and he became an integral part of the Harlem Renaissance.

Robeson first international artistic exploits were in the theatre in Great Britain. However, his renditions of spirituals, therein, became an integral part of the development of popular music in Great Britain in the 20th century. His theatrical role as Othello was the first significant portrayal by someone of African descent since Ira Aldridge's 19th century perfomances.

He became a supporter of the Republican forces of the Spanish Civil War and then became active in the Council on African Affairs (CAA). During World War II, he played Othello in the United States while supporting the country's war effort. After the war ended, the CAA was placed on the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO) and he was scrutinized during the age of McCarthyism.

Due to his decision to not recant his beliefs, he was denied an international visa, and his income plummeted. He settled in Harlem and published a periodical critical of US policies. His right to travel was restored by Kent v. Dulles, but his health soon broke down.

Early life

Childhood (1898–1915)

Paul Robeson was born in Princeton in 1898, to Reverend William Drew Robeson and Maria Louisa Bustill.[2] His mother was from a prominent Quaker family of mixed ancestry: African, Anglo-American, and Lenape.[3] His father, William, escaped from a plantation in his teens[4] and eventually became the minister of Princeton's Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church in 1881.[5] Robeson had three brothers, William Drew, Jr. (born 1881), Reeve (born c. 1887), and Ben (born c. 1893), and one sister, Marian (born c. 1895).[6]

In 1900, a disagreement between William and white financial supporters of Witherspoon arose with apparent racial undertones,[7] which were prevalent in Princeton.[8] William, who had the support of his entirely black congregation, resigned in 1901.[9] The loss of his position forced him to work menial jobs.[10] Three years later when Robeson was six, his mother, who was nearly blind, tragically died in a house fire.[11] Eventually, William became financially incapable of providing a house for himself and his children still living at home, Ben and Robeson, so they moved into the attic of a store in Westfield, New Jersey.[12]

William found a stable parsonage at the St. Thomas A. M. E. Zion in 1910,[13] where Robeson would fill in for his father during sermons when he was called away.[14] In 1912, Robeson attended Somerville High School,[15] where he performed in Julius Caesar, Othello, sang in the chorus, and excelled in football, basketball, baseball and track.[16] His athletic dominance elicited racial taunts which he ignored.[17] Prior to his graduation, he won a statewide academic contest for a scholarship to Rutgers.[18] He took a summer job as a waiter in Narragansett Pier, Rhode Island, where he befriended Fritz Pollard.[19]

Rutgers University (1915–1919)

In late 1915, Robeson became the third African-American student ever enrolled at Rutgers, and the only one at the time.[20] He tried out for the Rutgers Scarlet Knights football team,[21] and his resolve to make the squad was tested as his teammates engaged in unwarranted and excessive play, arguably precipitated by racism.[22] The coach, Foster Sanford, recognized his perseverance and allowed him onto the team.[23]

He joined the debate team[24] and sang off-campus for spending money,[25] and on-campus with the Glee Club informally, as membership required attending all-white mixers.[26] He also joined the other collegiate athletic teams.[27] As a sophomore, amidst Rutgers' sesquicentennial celebration, he was insultingly benched when a Southern team refused to take the field because the Scarlet Knights had fielded a Negro, Robeson.[28]

After a standout junior year of football,[29] he was recognized in The Crisis for his athletic, academic, and singing talents.[30] At what should have been a high point of his life,[31] his father fell grievously ill.[32] Robeson took sole responsibility to care for him, shuttling between Rutgers and Somerville.[33] His father soon died, and at Rutgers, Robeson expounded on the incongruity of African-Americans fighting to protect America (in World War I) and not being afforded the same opportunities as whites.[34]

He finished university with four annual oratorical triumphs[35] and varsity letters in multiple sports.[36] His play at end[37] won him first-team All-American selection, in both his junior and senior years. Walter Camp considered him the greatest end ever.[38] Academically, he was accepted into Phi Beta Kappa[39] and Cap and Skull.[40] His classmates recognized him[41] by electing him class valedictorian.[42] The Daily Targum published a poem featuring his achievements.[43] In his valedictorian speech, he exhorted his classmates to work for equality for all Americans.[44]

Columbia Law School (1919–1923)

Robeson entered New York University School of Law in the fall of 1919.[45] To support himself, he became an assistant football coach at Lincoln,[46] where he joined the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.[47] Harlem had recently changed its predominantly Jewish American population to an almost entirely African-American one,[48] and Robeson was drawn to it.[49] He transferred to Columbia Law School in February 1920 and moved to Harlem.[50]

Already well-known in the black community for his singing,[51] he was selected to perform at the dedication of the Harlem YWCA.[52] He began dating Eslanda "Essie" Goode, a histological chemist at NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital.[53] After Essie's coaxing,[citation needed], he gave his theatrical debut as Simon in Ridgely Torrence's Simon of Cyrene.[54] After a year of courtship, they were married in August 1921.[55]

He was recruited by Pollard to play for the NFL's Akron Pros, while he continued his law studies.[56] In the spring, he postponed school[57] to portray Jim in Mary Hoyt Wiborg's Taboo.[58] He then sang in a chorus in an Off-Broadway production of Shuffle Along[59] before he joined Taboo in Britain.[60] The play was adapted by director Mrs. Patrick Campbell to highlight his singing.[61] After the play ended, he befriended Lawrence Brown,[62] a classically trained musician,[63] before returning to Columbia while playing for the NFL's Milwaukee Badgers.[64] He ended his football career after 1922,[65] and months later, he graduated from law school.[66]

Theatrical ascension and ideological transformation (1923–1939)

Harlem Renaissance (1923–1927)

Robeson briefly worked as a lawyer, but he renounced a career in law due to extant racism.[67] Essie, the chief histological chemist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, financially supported them and they frequented the social functions at the future Schomburg Center.[68] In December, he landed the lead role of Jim in Eugene O'Neill's All God's Chillun Got Wings,[69] which culminated with Jim metaphorically consummating his marriage with his white wife by symbolically emasculating himself. Chillun's opening was postponed while a nationwide debate occurred over its plot.[70]

Chillun's delay led to a revival of The Emperor Jones with Robeson as Brutus, a role pioneered by Charles Sidney Gilpin.[71] The role terrified and galvanized Robeson as it was practically a 90-minute soliloquy.[72] Reviews declared him an unequivocal success.[73] Though arguably clouded by its controversial subject, his Jim in Chillun was less well received.[74] He deflected criticism of its plot by writing that fate had drawn him to the "untrodden path" of drama and the true measure of a culture is in its artistic contributions, and the only true American culture was African-American.[75]

The popular success of his acting placed him in elite social circles[76] and his ascension to fame, which was forcefully aided by Essie.[77] had occurred at a startling pace.[78] Essie's naked ambition for Robeson was a startling dichotomy to his insouciance.[79] She quit her job, became his agent, and negotiated his first movie role in a silent race film directed by Oscar Micheaux, Body and Soul.[80] To support a charity for single mothers, he headlined a concert singing spirituals.[81] He performed his repertoire of spirituals on the radio.[82]

Brown, who had become renown while touring with gospel singer Roland Hayes, stumbled on Robeson in Harlem.[83] The two ad-libbed a set of spirituals, with Robeson as lead and Brown as accompanist. This so enthralled them that they booked Provincetown Playhouse for a concert.[84] The pair's rendition of African-American folk songs and spirituals was captivating,[85] and Victor Records signed Robeson to a contract.[86]

The Robesons went to London for a revival of Jones, before spending the rest of the fall on holiday on the French Riviera socializing with Gertrude Stein and Claude McKay.[87] Robeson and Brown performed a series of concert tours in America from January 1926 until May 1927.[88] During a hiatus in New York, Robeson learned that Essie was several months pregnant.[89] Paul Jr. was born while Robeson and Brown toured Europe.[90] Essie experienced complications from the birth,[91] and by mid-December, her health had deteriorated dramatically. Ignoring her objections, her mother wired Robeson and he immediately returned to her bedside.[92] Essie completely recovered after a few months.[citation needed]

Show Boat, Othello, and marriage difficulties (1928–1932)

Robeson played the stevedore "Joe" in the London production of the American musical Show Boat, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.[93] His rendition of "Ol' Man River" became the benchmark for all future performers of the song.[94] Some black critics were not pleased with the play due to its usage of the word nigger.[95] It was, nonetheless, immensely popular with white audiences,[96] and it gained the attendance of Queen Mary.[97] He was summoned for a Royal Command Performance at Buckingham Palace in honor of the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII.[98] He was befriended by MPs from the House of Commons.[99] Show Boat continued for 350 performances and as of 2001, it remained the Royal's most profitable venture.[94] Feeling comfortable in London, the Robesons' bought a home, at a later recipient of the English Heritage Blue Plaque,[100] in Hampstead.[101] He reflected on his life in his diary and wrote that it was all part of a "'higher plan'" and "God watches over me and guides me. He's with me and lets me fight my own battles and hopes I'll win."[102] However, an incident at the Savoy Grill, wherein he was refused to be seated, sparked him to issue a press release portraying the insult which subsequently became a matter of public debate.[103]

Essie had learned early in their marriage that Robeson had been involved in extramarital affairs, but she tolerated them.[104] However, when she discovered that he was having an affair with a Ms. Jackson, she unfavorably altered the characterization of him in his biography,[105] and defamed him by describing him with "negative racial stereotypes", which he found appalling.[106] Despite her uncovering of this tryst, there was no public evidence that their relationship had soured.[107] In early 1930, they both appeared in the experimental classic Borderline,[108] and then returned to the West End for his starring role in Shakespeare's Othello, opposite Peggy Ashcroft as Desdemona.[109]

Robeson became the first black actor cast as Othello in Britain since Ira Aldridge.[110] The production received mixed reviews which pointed out Robeson's "highly civilized quality [but lacking the] grand style."[111] Drawn into an interview, he stated that the best way to diminish the oppression African-Americans faced was for his artistic work to be an example of what "men of my colour" could accomplish rather than to "be a propagandist and make speeches and write articles about what they call the Colour Question."[112]

After Essie's discovery of Robeson's affair with Ashcroft, she decided to seek a divorce and they split up.[113] While Jackson and he broached marriage,[114] he returned to Broadway as Joe in the 1932 revival of Show Boat, to critical and popular acclaim.[115] Subsequently, he received, with immense pride, an honorary master's degree from Rutgers.[116] Thereabout, his former football coach, Foster Sanford, advised him that divorcing Essie and marrying Jackson would do irreparable damage to his reputation.[117] Jackson's and Robeson's relationship ended in 1932,[118] following which Robeson and Essie reconciled, although their relation was permanently scarred.[119]

Ideological awakening (1933–1937)

Robeson returned to the theatre as Joe in "Chillun" in 1933 because he found the character stimulating.[120] He received no financial compensation for "Chillun", but he was a pleasure to work with.[121] The play ran for several weeks and was panned by critics, except for his acting.[122] He then returned to the US for a lucrative portrayal of Brutus in the film The Emperor Jones.[123] "Jones" became the first feature sound film starring an African American, a feat not repeated for more than two decades in the U.S. His acting was well-received, but offensive language in the script caused controversy.[124] On the film set he rejected any slight to his dignity, notwithstanding the widespread Jim Crow attitudes.[125] Although, the winter of 1932–1933 was the worst economic period in American history, he was unappreciative of the unfurling disaster.[126]

Post-production, Robeson returned home to England and publicly criticized African Americans' rejection of their own culture.[127] His comments brought rebuke from the New York Amsterdam News, which retorted that his elitism had made a "'jolly well [ass of himself].'"[128] He declared that he would reject any offers to perform European opera because the music had no connection to his heritage.[129] In early 1934, he enrolled in the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London to study Phonetics and Swahili, in addition to Igbo and Zulu. On September 20, 2006, Professor Philip Jaggar organised a celebratory tribute at SOAS.[130] His "sudden interest" in African history and its impact on culture[131] coincided with his essay "I Want to be African", wherein he wrote of his desire to embrace his ancestry.[132] He undertook Bosambo in the movie Sanders of the River,[133] which he felt would render a realistic view of colonial African culture.[citation needed] His friends in the anti-imperialism movement and association with British socialists led him to visit the USSR.[132] Robeson, Essie, and Marie Seton embarked to the USSR on an invitation from Sergei Eisenstein in December 1934.[134] During their trip, a stopover in Berlin enlightened Robeson to the racism in Nazi Germany,[135] and on his arrival in the USSR, he promulgated the irrelevance of his race which he felt in Moscow.[136]

When Sanders of the Rivers was released in 1935, it made him an international movie star.[137] However, his stereotypical portrayal of a colonial African[138] was seen as embarrassing to his stature as an artist[139] and damaging to his reputation.[140] The Commissioner of Nigeria to London protested the film as slanderous to his country,[141] and Robeson henceforth became more politically conscious of his roles.[142] In early 1936 he considered himself primarily apolitical,[143] however he decided to send his son to school in the Soviet Union in order to shield him from racist attitudes.[144] He then played the role of Toussaint Louverture in the eponymous play by C. L. R. James at the Westminster Theatre and appeared in the films Song of Freedom,[145] Show Boat,[146] Big Fella,[147] My Song Goes Forth (a.k.a. Africa Sings),[148] and King Solomon's Mines.[149] He was internationally recognized as the 10th-most popular star in British cinema.[150]

Spanish Civil War (1937–1939)

Robeson would later write the struggle against fascism during the Spanish Civil War was a turning point in his life, transforming him into a political activist and artist.[151] In 1937, he used his concert performances to advocate the Republican cause and the war's refugees.[152] He permanently modified his renditions of Ol' Man River from a show tune into a battle hymn of unwavering defiance.[153] His business agent expressed concern about his political involvement,[154] but Robeson overruled him and decided that contemporary events trumped commercialism[155] In Wales,[156] he commemorated the Welsh killed while fighting for the Republicans,[157] where he recorded a message which would become his epitaph:

After an invitation from J. B. S. Haldane,[159] he traveled to Spain in 1938 because he believed in the International Brigades's cause.[160] He visited the battlefront[161] and provided a morale boost to the Republicans at a time when their victory was unlikely.[162] Back in England, he hosted Jawaharlal Nehru to support Indian independence, wherein Nehru expounded on imperialism's affiliation with Fascism.[163] Robeson reevaluated the direction of his career and decided to focus his attention on utilizing his talents to promote causes which he cherished.[citation needed] and subsequently appeared in Plant in the Sun by Herbert Marshall[165]

Political activism (1939–1958)

Outbreak of World War II (1939–1943)

After the outbreak of World War II, Robeson returned to the US and became America's "no.1 entertainer"[166] with Ballad for Americans,[167] and The Proud Valley—the film he was most proud of.[168] At the Beverly Wilshire, the only hotel in Los Angeles willing to accommodate him, he spent two hours every afternoon sitting in the lobby. When asked why, he responded, "To ensure that the next time Black[s] come through, they'll have a place to stay."

With Max Yergan, Robeson co-founded the CAA. The CAA provided information about Africa across the US, particularly to African-Americans. It functioned as a coalition that included activists from varying leftist backgrounds.[citation needed] After Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, he participated in benefit concerts on behalf of the war effort.[citation needed]

He performed in Native Land, labeled "a Communist project"[169] which was based on the La Follette Committee's investigation of the repression of labor organizations.[170] He participated in the Tales of Manhattan, which he felt was "very offensive to my people", and consequently he announced that he would no longer act in films because of the demeaning roles available to black[s].[171] He performed at the Polo Grounds to support the USSR in the war, where he met two emissaries from the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Solomon Mikhoels and Itzik Feffer, an NKVD informant.[172]

The Broadway Othello and political activism (1943–1945)

Robeson reprised his role of Othello at the Shubert Theatre in 1943 under the direction of Margaret Webster.[citation needed] Stage actress Uta Hagen played Desdemona, and José Ferrer played Iago.[citation needed] He became the first African-American to play the role with a white supporting cast on Broadway where it was immensely popular.[citation needed] Contemporaneously, he addressed a meeting of Major League Baseball (MLB) club owners and MLB Commissioner Landis in a failed attempt to have them admit black players.[173] Subsequently, he toured North America with Othello until 1945,[citation needed] received a Donaldson Award[174] and was awarded the Spingarn medal by the NAACP.[175]

Onset of Cold War (1946–1948)

In 1946, he opposed a move by the Canadian government to deport thousands of Japanese Canadians,[176] and he telegraphed President Truman on the Lynching in the United States of four African Americans, demanding that the federal government "take steps to apprehend and punish the perpetrators ... and to halt the rising tide of lynchings.[177] He led a delegation to the White House to present a legislative and educational program aimed at ending mob violence; demanding that lynchers be prosecuted and calling on Congress to enact a federal anti-lynching law. He then warned Truman that if the government did not do something to end lynching, "the Negroes will".[178] Truman refused his request to issue a formal public statement against lynching, stating that it was not "the right time". Robeson also gave a radio address, calling on all Americans of all races to demand that Congress pass civil rights legislation.[179]

The CAA's most successful campaign was for South African famine relief in 1946.[citation needed]

On October 7, 1946, he testified before the Tenney Committee that he was not a Communist Party member.[180] The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) and the CAA was placed on the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO).[181]

Robeson sang and spoke in 1948 at an event organized by the Los Angeles CRC and labor unions to launch a campaign against job discrimination, for passage of the federal Fair Employment Practices Act also known as Executive Order 8802, anti-lynching and anti-poll tax legislation, and citizens’ action to defeat the county loyalty oath climate.

In 1948, Robeson was preeminent in the campaign to elect Progressive Party presidential candidate Henry A. Wallace, who had served as Vice President under Franklin D. Roosevelt. Wallace was running on an anti-lynching, pro-civil rights platform and had attracted a diverse group of voters including Communists, liberals and trade unionists. On the campaign trail, Robeson went to the Deep South, where he performed for "overflow audiences... in Negro churches in Atlanta and Macon."[182]

Robeson's belief that the labor movement and trade unionism were crucial to the civil rights of oppressed people of all races became central to his political beliefs.[183] Robeson's close friend, the union activist Revels Cayton, pressed for "black caucuses" in each union, with Robeson's encouragement and involvement.[183]

In 1948, he opposed a bill calling for registration of Communist Party members and appeared before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary. Questioned about his affiliation with the Communist Party, he refused to answer, stating "Some of the most brilliant and distinguished Americans are about to go to jail for the failure to answer that question, and I am going to join them, if necessary."[citation needed]

Controversies and international travels (1949)

In early 1949 Robeson learned that his performances were canceled at the FBI's behest. His recordings were commercially banned, so he had to go overseas to work.[184] As a precondition to recover his right to travel, he agreed to be remain apolitical.[185] However, while on tour, he spoke at the World Peace Council,[186] whereat, although the original text of his speech was anti-imperialistic,[187] his speech was reported as equating America with a Fascist state[188]—which he flatly denied.[189] Nevertheless, the speech publicly attributed to him was a catalyst in him becoming an enemy of mainstream America.[190] At the urging of the State Department, Roy Wilkins stated that despite lynchings in the US, African Americans would always be loyal.[191]

In 1949, he spoke in favor of the liberty of twelve Communists, including his long-time friend, Benjamin J. Davis, Jr. convicted during the Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders.[citation needed]

Robeson traveled to Moscow in June, and was unable to find Itzik Feffer. He let Soviet authorities know that he wanted to see him.[192] Reluctant to lose Robeson as a propagandist for the USSR,[193] the Soviets brought Feffer from prison to him.[194] Feffer told him that Mikhoels had been murdered, and he would be summarily executed.[194] To protect the USSR's reputation, Robeson kept the meeting secret, except from his son, for the rest of his life.[193] Back in the US to keep the right wing from taking the moral high ground, he denied that any persecution existed in the USSR; "it was not [Robeson's] finest hour".[195]

The controversy over his Paris speech caused the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to seek Jackie Robinson's testimony[196] in order to politically isolate Robeson.[citation needed] Robinson testified that Robeson's statements, if accurately reported, were 'silly'.[197] Days later, the announcement of a concert headlined by Robeson in Westchester County, New York provoked local outcry for the use of their community to support subversives.[198] At the concert, the hyperbole from the local press helped initiate the Peekskill Riots.[199] Contemporaneously, criticism of Robeson had become, even among liberals, de rigueur.[200]

Blacklist and passport confiscation (1950–1955)

College Football: and All America Review, reviewed as "the most complete record on college football",[201] omitted Robeson's name from its listing of the 1917 college All-American team,[202] nor is he listed as ever playing for Rutgers.[203] Months later, NBC canceled Robeson's scheduled appearance on former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt's television program.[204] A spokesman for NBC declared either that, depending on sources, Robeson's appearance had not been approved by NBC headquarters,[205] or Robeson would "never appear on NBC."[citation needed] Press releases of the Civil Rights Congress objected that "censorship of Mr. Robeson's appearance on TV is a crude attempt to silence the outstanding spokesman for the Negro people in their fight for civil and human rights [and that our] basic democratic rights are under attack under the smoke-screen of anti-Communism." Protesters picketed NBC offices and protests arrived from numerous public figures, organizations and others.[citation needed]

In 1950, the State Department denied Robeson a passport and issued a "stop notice" at all ports, effectively confining him within the US. Robeson was not even allowed to travel to Canada or Mexico, countries that US citizens could visit without a passport. Far from seeking to revoke his citizenship and deport him, FBI and state department records indicate that the US government believed that a blacklisted existence inside the US borders would offer Robeson less freedom of expression than his presence internationally.[206] When Robeson and his lawyers met with officials at the State Department and asked why it was "detrimental to the interests of the United States Government" for him to travel abroad, they were told that "his frequent criticism of the treatment of blacks in the United States should not be aired in foreign countries"—it was a `family affair'."[207] When Robeson inquired about being re-issued a passport, the State Department declined, citing Robeson's refusal to sign a statement guaranteeing "not to give any speeches while outside the U.S."

"The US government [had]revoked his passport and rejected his appeal because as a spokesperson for civil rights he had been 'extremely active in behalf of the independence for the colonial peoples of Africa.'"[208]

In 1951 an article titled "Paul Robeson - the Lost Shepherd" was published in The Crisis[209] although Paul Jr. suspected it was authored by Earl Brown.[210] J. Edgar Hoover and the United States State Department arranged for the article to be printed and distributed in Africa[211] in order to defame Robeson's reputation and reduce his and Communists popularity in colonial countries.[212] Another article by Wilkins denounced Robeson as well as the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) in terms consistent with the anti-Communist FBI propaganda.[213]

On December 17, 1951 Robeson presented to the United Nations an anti-lynching petition, "We Charge Genocide".[214] The document asserted that the US federal government, by its failure to act against lynching in the US, was "guilty of genocide" under Article II of the UN Genocide Convention.

In 1952 Robeson was awarded the International Stalin Prize by the USSR.[215] Unable to travel to Moscow, he accepted the award in New York.[216] In April 1953, shortly after Stalin's death, Robeson penned To You My Beloved Comrade, praising Stalin as dedicated to peace and a guide to the world: "Through his deep humanity, by his wise understanding, he leaves us a rich and monumental heritage."[217] Robeson's opinion on the USSR kept his passport out of reach and stopped his return to the entertainment industry and the civil rights movement.[218] In his opinion, the USSR was the guarantee of political balance in the world.[219]

In a symbolic act of defiance against the travel ban, labor unions in the US and Canada organized a concert at the International Peace Arch on the border between Washington state and the Canadian province of British Columbia.[220] Robeson returned to perform a second concert at the Peace Arch in 1953,[221] and over the next two years two further concerts were scheduled. In this period, with the encouragement of his friend the Welsh politician Aneurin Bevan, Robeson recorded a number of radio concerts for supporters in Wales.

Under the weight of internal disputes, government repression, and financial hardships, the CAA disbanded in 1955.

End of McCarthyism (1956–1957)

In 1956, Robeson was called before HUAC after he refused to sign an affidavit affirming that he was not a Communist. In response to questions concerning his alleged party membership, Robeson first insisted that the Communist Party was a legal party and invited its members to join him in the voting booth, then he invoked the Fifth Amendment and refused to respond. Robeson refused to discuss Stalin, calling it "a question for the Soviet Union", instead lambasting committee members on civil rights issues and the enslavement and exploitation of blacks throughout American history. Asked why he had not remained in the USSR, he replied that "because my father was a slave and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you and no fascist-minded people will drive me from it! Is that clear?"[citation needed]

Campaigns were simultaneously launched in the US and UK to protest the passport ban. In the UK, The National Paul Robeson Committee was formed, sponsored by Members of Parliament as well as writers, scholars, actors, lawyers, trade union leaders and others. The Committee began a "Let Paul Robeson Sing" mass petition, which gathered signatures from tens of thousands of supporters. Over the next four years, many prominent figures in Britain argued for the restoration of his right to travel. The group held a conference and concert at St Pancras Town Hall, London headed by Cedric Belfrage, on May 26, 1957 with Robeson singing from New York over a telephone connection.[222]

Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalinism at the 1956 Party Congress silenced Robeson on Stalin, though he continued to praise the USSR[223] and in so doing imitated the defendants sent to their death in the Trial of Sixteen in 1936.[citation needed]

In 1956, Robeson left the US for the first time since the travel ban, performing concerts in two Canadian cities in March. That year Robeson, along with close friend W. E. B. Du Bois, compared the anti-Stalinist revolution in Hungary to the "same sort of people who overthrew the Spanish Republican Government" and supported the Soviet invasion and suppression of the revolt.[224]

In 1957, Robeson was invited by Welsh miners to be the honored guest at the annual Eisteddfod Music Festival. An appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States to reinstate his confiscated passport had been rejected, but through the newly completed trans-Atlantic telephone hook-up between New York and Porthcawl, Wales, Robeson was able to sing to the 5,000 gathered there as he had earlier in the year to London. Journalist Gil Noble called the concert "perhaps the most emotional and moving in Robeson's long concert career."[citation needed]

Because of the controversy surrounding him, Paul Robeson's recordings and films lost mainstream distribution and he was universally condemned in the mainstream U.S press. During the height of the Cold War it became increasingly difficult in the US to hear Robeson sing on commercial radio, buy his music or to see his films.

Due to his blacklisting within the mainstream media, the concert stage, theater, radio, film and the civil rights movement, Robeson became a virtual nonperson."[225]

Passport restored (1958–1963)

Comeback international tours (1958–1960)

Robeson's autobiography, Here I Stand, was published in 1958. As part of his "comeback", he gave two sold-out recitals at Carnegie Hall.[citation needed] After Kent v. Dulles, his passport was restored in May 1958,[226] and he left for London.[227]

Robeson and Essie began traveling extensively, using London as their base. During this period Robeson was under constant surveillance by the CIA, MI6 and the State Department. In the United Kingdom, he found himself deluged with professional offers.

In August 1959 he left for Moscow where he received a tumultuous reception and needed a police escort at the airport.[228] A crowd of eighteen thousand people filled the Lenin Stadium (Khabarovsk) to capacity on August 17 where Robeson sang classic Russian songs along with American standards. Robeson and Essie then flew to Crimea to spend time at Yalta resting, working with a documentary film crew and spending time with Nikita Khrushchev. Robeson also visited Young Pioneer camp Artek[229] before returning to the UK.

On October 11, 1959 Robeson took part in a historic service at St.Paul's Cathedral, the first black performer to sing there. Four thousand people attended the evensong performance with hundreds overflowing onto the streets.[230] The State Department had circulated negative literature about him through the media in India; one censored CIA memo suggested that Robeson's appearance could be used to thwart the desegregation of a swimming pool.[231]

On a trip to Moscow, Robeson experienced bouts of dizziness and heart problems, and he was hospitalized for two months while Essie was diagnosed with operable cancer.[232]

Robeson recovered and returned to the UK to fulfill his engagements. In 1958, he visited the National Eisteddfod in Ebbw Vale as the guest of the local MP Aneurin Bevan, revisited his ties to the black community in Cardiff's Butetown and gave performances throughout Europe. During his run at the Royal Shakespeare Company playing Othello in Tony Richardson's 1959 production at Stratford-upon-Avon, he befriended actor Andrew Faulds whose family hosted him in the nearby village of Shottery. Robeson inspired him to take up a career in politics after admonishing him for being apolitical.[233] The production of Othello was geared towards Robeson's health concerns but gave him a lucrative seven month run and chance to participate in an updated version of the play. In 1960, in what would prove to be his final concert performance in Great Britain, Robeson sang with the Welsh Male Voice Choir, Côr Meibion Cwmbach, to raise money for the Movement for Colonial Freedom at the Royal Festival Hall.

Robeson embarked on a a two month concert tour of Australia and New Zealand in October 1960, with Essie, primarily to generate money,[234] at the behest of Bill Morrow.[235] After appearing at the Brisbane Festival Hall, they went to Auckland where Robeson first acknowledged that he needed money and then reaffirmed his support of Marxism,[236] denounced the inequality faced by the Māori and efforts to denigrate their culture.[237]

In a message to the Melbourne Peace Conference some time around December 1960/January 1961, Robeson said "...the people of the lands of Socialism want peace dearly".[238]

Back in Australia, he was introduced to Faith Bandler who enlightened the Robesons concerning the deprivation endured by Australian Aborigines.[239] Robeson became enraged and demanded the Australian government provide the Aborigines citizenship and equal rights.[240] He attacked the view of the Aborigines as unsophisticated and uncultured,[citation needed] and declared, "'there's no such thing as a backward human being, there is only a society which says they are backward.'" Robeson advocated for trade unions and supported their cause with impromptu performances, including the singing of Joe Hill at the Sydney Opera House construction site. He was given art and artifacts from Aborigine culture to signify trade union support for Aboriginal rights.[241] The Robesons sought out the Aborigines as much as possible, and they became further enlightened to their treatment.[242] Robeson, at the age of 62,[citation needed] won adulation in all artistic phases of this, his final major concert tour.[citation needed] Robeson left Australia as a respected, albeit controversial figure and his support for Aboriginal rights had a profound affect in Australia over the next decade.[243]

Health breakdown (1961–1963)

Back in London, he planned his US return to participate in the Civil Rights Movement, stopping off in Africa, China and Cuba along the way. Essie argued to stay in London, fearing that he'd be "killed" if he did and would be "unable to make any money" due to harassment by the US government. Robeson disagreed and made his own travel arrangements, stopping off in Moscow in March 1961.[244]

During an uncharacteristically wild party in his Moscow hotel room, he locked himself in his bedroom and attempted suicide by cutting his wrists.[245] Three days later, under Soviet medical care, he told his son that he felt extreme paranoia, thought that the walls of the room were moving and, overcome by a powerful sense of emptiness and depression, tried to take his own life.[246]

Paul Jr. believed that his father's health problems stemmed from attempts by CIA and MI5 to "neutralize" his father.[247][248] He remembered that his father had had such fears prior to his prostate operation.[249] He said that three doctors treating Robeson in London and New York had been CIA contractors,[247] and that his father's symptoms resulted from being "subjected to mind depatterning under MKULTRA", a secret CIA programme.[250] Martin Duberman claimed that Robeson's health breakdown was probably brought on by a combination of factors including extreme emotional and physical stress, bipolar depression, exhaustion and the beginning of circulatory and heart problems. "[E]ven without an organic predisposition and accumulated pressures of government harassment he might have been susceptible to a breakdown".[245]

Robeson stayed at the Barvikha Sanatorium until September 1961, when he left for London. There his depression reemerged, and after another period of recuperation in Moscow, he returned to London. Three days after arriving back he became suicidal and suffered a panic attack while passing the Soviet Embassy.[251] He was admitted to The Priory hospital, where he underwent electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and was given heavy doses of drugs for nearly two years, with no accompanying psychotherapy.[252]

During his treatment at the Priory, Robeson was being monitored by the British MI5.[253] Both intelligence services were well aware of Robeson's suicidal state of mind. An FBI memo described Robeson's debilitated condition, remarking that his "death would be much publicized" and would be used for Communist propaganda, necessitating continued surveillance.[254] Numerous memos advised that Robeson should be denied a passport renewal which would ostensibly jeopardize his fragile health and his recovery process.[245]

In August 1963, disturbed about his treatment, friends had him transferred to the Buch Clinic in East Berlin.[255] Given psychotherapy and less medication, his physicians found him still "completely without initiative" and they expressed "doubt and anger" about the "high level of barbiturates and ECT" that had been administered in London. He rapidly improved, though his doctor stressed that "what little is left of Paul's health must be quietly conserved."[256]

Withdrawal from public life (1963–1976)

In 1963, Robeson returned to the US and for the remainder of his life lived in seclusion.[257] He momentarily assumed a role in the civil rights movement,[247] making a few major public appearances before falling seriously ill during a tour. Double pneumonia and a kidney blockage in 1965 nearly killed him.[257] He lived in Harlem with his wife.

On January 15, 1965, Robeson gave the eulogy at the Harlem funeral of Lorraine Hansberry recalling her work at Freedomways and her contributions to civil rights. Robeson was also contacted by both Bayard Rustin and James L. Farmer, Jr. about the possibility of becoming involved with the mainstream of the Civil Rights movement.[258] Due to Rustin's past anti-Communist stances, Robeson declined to meet with him. Robeson eventually met with Farmer but because he was asked to denounce Communism and the USSR in order to assume a place in the mainstream, Robeson adamantly declined.[259]

After Essie died of cancer in December 1965,[260] Robeson moved in with his son's family in an Upper West Side apartment in New York City[261] and in 1968, settled at his sister's home in Philadelphia.[262]

Retirement

In 1968, in honor of Paul Robeson's 70th birthday, celebrations were held in in East Germany, at the Royal Festival Hall in London, and in Moscow. The black commission of the CPUSA celebration remarked that "the white power structure has generated a conspiracy of silence around Paul Robeson. It wants to blot out all knowledge of this pioneering Black American warrior..."[263]

Despite Robeson's lengthy theater career, Brooks Atkinson, The New York Times theater critic from 1925 to 1960, included just a one-sentence reference to Robeson in his 1970 book Broadway, advertised as "an history of American theater".[264][265] Atkinson chronicled African-American performers, Show Boat and Eugene O'Neill, but only mentions Robeson briefly in context with Othello. In the early 1970s, The New York Times and The New York Daily News both ran extensive pieces on black actors who played Othello with no mention of Robeson.[264]

In these years Robeson was honored by accolades and celebrations, both in the US and internationally, including public arenas that had previously shunned him.[266]

He saw few visitors aside from close friends and gave few statements apart from messages to support current civil rights and international movements, feeling that his record "spoke for itself".[266] Though he had withdrawn from the public eye, close friends and family disputed rumors in the mainstream press that he was "broken" and "disillusioned".[262] He spent his final, unapologetic years in Philadelphia.[267]

In 1971, Actor's Equity created the Paul Robeson award to recognize the principles by which he lived.[268] A sold-out performance was held at Carnegie Hall to salute his 75th birthday in 1973. Birthday greetings arrived from several world-wide prominent officials or organizations. He was unable to attend because of illness, but a taped message from him was played which said in part, "Though I have not been able to be active for several years, I want you to know that I am the same Paul, dedicated as ever to the worldwide cause of humanity for freedom, peace and brotherhood."[citation needed]

Death and funeral

On January 23, 1976 in Philadelphia, following complications of a stroke, Robeson died, at the age of 77.[269] He lay in state in Harlem for two days[270] and his funeral was held at his brother Ben's former parsonage, Mother AME Zion Church,[271] where Bishop J. Clinton Hoggard performed the eulogy.[272] His pall bearers included Harry Belafonte, Pollard, and others.[citation needed] He was interred in the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York.[citation needed]

Legacy and honors

After his death, "[t]he white [American] press, after decades of harassing Robeson, now tipped its hat to a 'great American,' paid its gingerly respect to him and and the vituperation leveled at [him during his life] to the Bad Old Days of the Cold War, and implied those days were forever gone, they downplayed the racist component central to his persecution, and ignored the continuing inability of white America to tolerate a black maverick who refused to bend. The black [American] press made no such mistakes. It had never, overall, been as hostile to [him] as the white [American] press, (though at some points in his career, nearly so)."[271] Robeson was a "Gulliver among the Lilliputians [and his life would] always be a challenge and a reproach to white and Black America."[273] Poitier proclaimed, "When Paul Robeson died, it marked the passing of a magnificent giant whose presence among us conferred nobility upon us all..."[citation needed]

Several public and private establishments he was associated with have been land marked,[274] or named after him.[275] His efforts to end Apartheid in South Africa were posthumously rewarded by the United Nations General Assembly in 1978.[276] In 1995, he was named to the College Football Hall of Fame.[277] In the centenary of his birth, which was commemorated around the world,[citation needed] he was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award,[278] and his name was placed on a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[279] In 2004, a US postage stamp was created to recognize his dignified stance against the "conventional wisdom" of the United States Government during the Cold War.[280]

Early in his life, he was one of the most influential participants in the Harlem Renaissance.[281] Few, if any, have achieved the level of excellence in athletics and academics which he accomplished.[citation needed] His achievements were all the more incredible given the barriers of racism that he had to surmount.[282] Early in his theatrical career, his drawing attention of the extant racism in England brought public awareness to a problem that had been thought previously solved[citation needed] and his re-emphasis on the Negro spirituals was influential in the music of Great Britain.[citation needed] Robeson brought Negro spirituals into the center of the American songbook[283] His portrayal of leading roles, without the requisite subservience typical of African-Americans at the time,[284] were later acclaimed by James Earl Jones, Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte as the first to display dignity for black actors and pride in African heritage.[285]

"After McCarthyism, the two towering figure of anti-colonialism in the 1940s, Robeson and W. E. Du Bois, would never again have a voice in American politics, but the [African independence movements] of the late 1950s and 1960s, would vindicate their anti-colonial analysis..."[286] However in light of Khruschev's revelations of the atrocities committed by Stalin during his regime, his unrepentant support of Stalin was a stain on his lifelong human rights activism.[citation needed]

As of 2011[update], Robeson's run of Othello was the longest of any Shakespeare play on Broadway, running for 296 performances.[citation needed]

Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist won an Academy Award for best short documentary in 1980.[citation needed]

Beginning in 1978, Robeson's films were finally shown on American television, with Show Boat debuting on cable television in 1983.[citation needed]

The Welsh people maintained their loyalty to Robeson and in Cardiff in 2001, the exhibition Let Paul Robeson Sing! was unveiled.[287]

American Jews continue to celebrate his memory as an ally.[288]

He was the first artist to refuse to play to segregated audiences.[citation needed]

Robeson archives exist at the Academy of Arts;[289] Howard University,[290] and the Schomburg Center.[citation needed] In 2010 Susan Robeson launched a project by Swansea University and the Welsh Assembly, to create an online learning resource in her grandfather's memory.[citation needed]

"Robeson connected his own life and history not only to his fellow Americans and to his people in the South but to all the people of Africa and its diaspora whose lives had been fundamentally shaped by the same processes that had brought his foremothers and forefaters to America."[291] However, a consensus definition of his legacy remains controversial,[292] but to deny his courage, in the face of public and governmental pressure, is to defame his courage.[citation needed]

Filmography

|

|

|

Notes

- ^ "Thorpe-M'Millan Fight Great Duel: Robeson Scores Both Touchdowns for Locals Against Indians". The Milwaukee Sentinel. 1922-11-20. p. 7.; cf. Badgers Trim Thorpe's Team

- ^ Robeson, Paul Jr. (2001). "Motherless Child (1898–1919)". The Undiscovered Paul Robeson, An Artist's Journey, 1898–1939 (PDF). New York: Wiley. p. 3. ISBN 0-471-24265-9.; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 18, Duberman: 4–5.

- ^ Brown: 5–6, 145–149; cf. Robeson, 2001: 4–5; Boyle and Bunie: 10–12.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 4, 337–338; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 4, Duberman: 4, Brown: 9–10

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 5–6, 14; cf. Robeson 2001: 4–5, Duberman: 4–6, Brown: 17, 26.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 3; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 18, Brown: 21

- ^ Duberman: 6–7; cf. Robeson, 2001: 5–6, Boyle and Bunie: 18–20.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 16–17; cf. Duberman: 12.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 5–6; cf. Duberman: 6–9, Boyle and Bunie: 18–20, Brown: 26.

- ^ Duberman: 9; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 21, Robeson 2001: 6–7, Brown: 28.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 22–23; cf. Duberman: 8, Robeson 2001: 7–8, Brown: 25–29.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 11; cf. Duberman: 9, Boyle and Bunie: 27–29.

- ^ Duberman: 9–10; cf. Brown: 39, Robeson 2001: 13–14.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 17; cf. Duberman: 30, Brown: 46–47.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 37–38; cf. Duberman: 12, Brown: 49–51.

- ^ Duberman: 13–16; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 34–36, Brown: 43, 46, 48–49.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 37–38; cf. Robeson: 16, Duberman: 13–16, Brown: 46–47.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 41–42; cf. Brown: 54–55, Duberman: 17, Robeson 2001: 17–18; contra. The dispute is over whether it was a one-year or four-year scholarship. Robeson Found Emphasis to Win Too Great in College Football 1926-03-13

- ^ Duberman: 11; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 40–41, Robeson: 18–19, Brown: 53–54, 65, Carroll: 58.

- ^ Duberman: 19; cf. Brown: 60, 64, Gilliam: 15, Robeson 2001: 20.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 45–49; cf. Duberman: 19, 24, Brown: 60, 65.

- ^ Duberman: 20–21; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 49–50, Brown: 61–63.

- ^ Van Gelder, Robert (1944-01-16). "Robeson Remembers: An interview with the Star of Othello, Partly about his Past". New York Times. pp. X1.; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 49–50, Duberman: 20–21, Robeson 2001: 22–23.

- ^ Yeakey, Lamont H. (Autumn, 1973). "A Student Without Peer: The Undergraduate College Years of Paul Robeson" (PDF). Journal of Negro Education. 42 (4): 499. JSTOR 2966562.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Duberman: 24; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 54, Brown: 71, Robeson 2001: 28, 31–32.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 54; Duberman: 24, Levy: 1–2, Brown: 71, Robeson 2001: 28.

- ^ Duberman: 24; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 54, Brown: 70, Robeson 2001: 35.

- ^ Brown 68–70; cf. Duberman: 22–23, Boyle and Bunie: 59–60, Robeson 2001: 27, Pitt: 42.

- ^ Duberman: 22, 573; cf. Robeson 2001: 29–30, Brown: 74–82, Boyle and Bunie: 65–66

- ^ Du Bois, W. E. B. (March 1918). "Men of the Month". The Crisis. 15 (5): 229–232.; cf. Marable: 171?

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 68.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 33; cf. Duberman: 25, Boyle and Bunie: 68–69, Brown: 85–87.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 68–69.

- ^ Duberman: 25; cf. Boyle and Bunie 68–69, Brown: 86–87, Robeson 2001: 33.

- ^ Duberman: 24; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 69, 74, 437, Robeson 2001: 35

- ^ "Hall of Fame: Robeson". Record-Journal. 1995-01-19. p. 20.; The number of letters varies between 12 and 15 based on author; cf. Duberman, p. 22, Boyle and Bunie: 73, Robeson 2001: 34–35.

- ^ Jenkins, Burris (1922-09-28). "Four Coaches—O'Neill of Columbia, Sanderson of Rutgers, Gargan of Fordham, and Thorp of N.Y.U.—Worrying About Outcome of Impending Battles". The Evening World. p. 24.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 66; cf. Duberman: 22–23, Robeson 2001: 30, 35

- ^ "Who Belongs to Phi Beta Kappa?". The Phi Beta Kappa Society. Archived from the original on 2012-01-21.; cf. Brown: 94, Boyle and Bunie: 74, Duberman: 24.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 74; cf. Duberman: 26, Brown: 94.

- ^ Brown: 94–95; cf. Duberman: 30, Boyle and Bunie:75–76, Harris: 47.

- ^ Duberman: 26; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 75, Brown: 94, Robeson 2001: 36.

- ^ Kirshenbaum, Jerry (1972-03-27). "Paul Robeson: Remaking A Fallen Hero". Sports Illustrated. 36 (13): 75–77.

- ^ Robeson, Paul Leroy (1919-06-10). "The New Idealism". The Targum. 50 (1918–19): 570–571.; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 76, Duberman: 26–27, Brown: 95, Robeson 2001: 36–39.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 43; cf. Boyle and Bunie; 78–82, Brown: 107.

- ^ Duberman: 34; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 82, Robeson 2001: 44, Carroll: 140–141.

- ^ Brown: 111; cf. Gilliam: 25, Boyle and Bunie: 53; Duberman: 41

- ^ Carley, Rachel (1981-02-03), "Schomburg Collection for Research in Black Culture" (PDF), Landmarks Preservation Committee, p. 4

- ^ Robeson 2001: 43

- ^ Robeson 2001: 43–44; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 82, Brown: 107–108.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 143; cf. Robeson 2001: 45.

- ^ Weisenfeld: 161–162.

- ^ Duberman: 34–35, 37–38; Boyle and Bunie: 87–89, Robeson 2001: 46–48.

- ^ Peterson: 93; cf. Robeson 2001: 48–49; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 89, 104, Who's Who New York Times 1924-05-11

- ^ Robeson 2001: 50–52; cf. Duberman: 39–41, cf. Boyle and Bunie: 88–89, 94, Brown: 119.

- ^ Levy 2000: 30; cf. Akron Pros 1920 by Bob Carrol, John Carroll p. 147–148, Robeson 2001: 53.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 104–105.

- ^ Darnton, Charles (1922-04-05). ""Taboo" Casts Voodoo Spell". The Evening World. p. 24.; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 100–105, Review of Taboo, Duberman: 43.

- ^ Wintz: 6–8; cf. Duberman 44–45, Robeson 2001: 57–59, Boyle and Bunie: 98–100.

- ^ Duberman: 44–45; cf. Brown: 120, Robeson 2001: 57–59, Boyle: 100–101.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 105–107; cf. Brown: 120, Duberman: 47–48, 50, Robeson 2001: 59, 63–64.

- ^ Brown: 120–121; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 105–106.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 139

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 108–109; cf. Robeson 2001: 68–69, Duberman: 34, 51, Carrol: 151–152.

- ^ Levy: 31–32; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 111.

- ^ Duberman: 54–55; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 111–113, Robeson 2001: 71, Brown: 122.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 111–114; cf: Duberman: 54–55, Robeson 2001: 71–72, Gillam: 29.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 115; cf. History, Schomburg Unit Listed as Landmark: Spawning Ground of Talent 40 Seats Are Not Enough Plans for a Museum

- ^ Robeson 2001: 73; cf. Duberman: 52–55, Boyle and Bunie: 111, 116–117.

- ^ "All God's Chillun". Time. March 17, 1924.

The dramatic miscegenation will shortly be enacted ... [produced by the Provincetown Players, headed by O'Neill], dramatist; Robert Edmund Jones, artist, and Kenneth Macgowan, author. Many white people do not like the [plot]. Neither do many black.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); cf. Duberman: 57–59, Boyle and Bunie: 118–121, Gillam: 32–33. - ^ Robeson 2001: 73–76; cf. Gillam: 36–37, Duberman: 53, 57–59, 61–62, Boyle and Bunie: 90–91, 122–123.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 123

- ^ Madden, Will Anthony (1924-05-17). "Paul Robeson Rises To Supreme Heights In "The Emperor Jones". Pittsburgh Courier. p. 8.; cf. Corbin, John (1924-05-07). "The Play; Jazzed Methodism" New York Times p. 18., Duberman: 62–63, Boyle and Bunie: 124–125.

- ^ Young, Stark (1924-08-24). "The Prompt Book". New York Times. pp. X1.; Chicago Tribune entitled: "All God's Chillun" Plays Without a Single Protest, Boyle and Bunie: 126–127, Duberman:64–65.

- ^ Robeson, Paul (2000). "An Actor's Wanderings and Hopes". The Messenger Reader. New York: The Modern Library. pp. 292–293. ISBN 0-375-75539-X.

And there is an 'Othello' when I am ready...One of the great measures of a people is its culture. Above all things, we boast that the only true artistic contributions of America are Negro in origin. We boast of the culture of ancient Africa...[I]n any discussion of art or culture,[one must include] music and the drama and its interpretation...So today Roland Hayes is infinitely more of a racial asset than many who 'talk' at great length. Thousands of people hear him, see him, are moved by him, and are brought to a clearer understanding of human values. If I can so something of a like nature, I shall be happy. I shall be happy. My early experiences give me much hope.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help); cf. Robeson, Paul (1925-01). "An Actor's Wanderings and Hopes". The Messenger 7 (1): 32 - ^ Gillam: 38–40; cf. Duberman: 68–71, 76, Sampson: 9.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 142–143; cf. "I Owe My Success To My Wife," Says Paul Robeson, Star In O'Neill's Drama

- ^ Robeson 2001: 84.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 84; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 149, 152.

- ^ Nollen: 14, 18–19, Duberman: 67, Boyle and Bunie: 160, Gillam: 43.

- ^ "Robeson to Sing for Nursery Fund: Benefit to Be Given in Greenwich Village Theatre March 15". New York Amsterdam News. 1925-03-11. p. 9.

- ^ Coates, Ulysses (1925-04-18). "Radio". Chicago Defender. pp. A8. cf. Robeson to Sing [Spirituals] Over Radio 1925-04-08

- ^ Duberman: 78; Boyle and Bunie: 139, Robeson 2001: 85.

- ^ Duberman: 79; cf. Gilliam: 41–42, Boyle and Bunie: 140, Robeson 2001: 85–86.

- ^ "Clara Young Loses $75,000 in Jewels". New York Times. 1925-04-20. p. 21.; cf. Paul Robeson, Lawrence Brown Score Big New York Success With Negro Songs, Music, Duberman: 80–81.

- ^ Duberman: 82, 86, Boyle and Bunie: 149, Robeson 2001: 93, Robeson on Victor 1925-09-16

- ^ Gillam: 45–47; cf. Duberman: 83, 88–98, Boyle and Bunie: 161–167, Robeson 2001: 95–97.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie:169–184; cf. Duberman: 98–106, Gillam: 47–49.

- ^ Duberman: 106; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 184.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 143; cf. Duberman: 106 Boyle and Bunie: 184.

- ^ Duberman: 110; cf. Robeson 2001: 147, Gillam: 49

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 186; cf. Duberman: 112, Robeson 2001: 148

- ^ "Drury Lane Theatre: 'Showboat'" (PDF). The Times. 1928-05-04. p. 14.

Mr. Robeson's melancholy song about the 'old river' is one of the two chief hits of the evening.

; Duberman: 113–115, Boyle and Bunie: 188–192, Robeson 2001: 149–156. - ^ a b Boyle and Bunie: 192.

- ^ Rogers, J A (1928-10-06). "'Show Boat' Pleasure-Disappointment": Rogers Gives New View Says Race Talent Is Submerged". Pittsburgh Courier. pp. A2.

[Show Boat] is, so far as the Negro is concerned, a regrettable bit of American niggerism introduced into Europe.

; Duberman: 114, Gilliam: 52. - ^ "Mrs. Paul Robeson Majestic Passenger: Coming to Settle Business Affairs of Her Distinguished Husband". New York Amsterdam News. 1928-08-22. p. 8.; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 193–197; cf. Duberman: 114, Gilliam: 52.

- ^ Sources differ on whether it was the Queen, or the King and Queen that attended. Boyle and Bunie: 192; cf. Robeson 2001: 155.

- ^ "Sings For Prince Of Wales". Pittsburgh Courier. 1928-07-28. p. 12.; cf. Duberman: 115, Boyle and Bunie: 196, Robeson 2001: 153.

- ^ "English Parliament Honors Paul Robeson". Chicago Defender. 1928-12-01. pp. A1.; cf. Seton 1978: 30; cf. Robeson 2001: 155, Boyle and Bunie: ?

- ^ "Robeson, Paul (1898–1976), Jan. 20".

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 205–207; cf. Robeson 2001: 153–156, Gilliam: 52, Duberman: 118.

- ^ Duberman: 126–127.

- ^ Duberman: 123-124

- ^ Duberman, Martin (1988-12-28). "Writing Robeson". The Nation. 267 (22): 33–38.; cf. Gilliam: 57, Boyle and Bunie: 159–160, Robeson 2001: 100–101.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 163–165.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 172–173; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 230–234, Duberman: 139–140.

- ^ Duberman: 143–144; cf. Robeson 2001: 165–166.

- ^ Nollen: 24; cf. Duberman: 129–130, Boyle and Bunie: 221–223.

- ^ Duberman: 133–138; Gilliam: 59–60.

- ^ Morrison: 114; cf. Swindall 2011: 23, Robeson 2001: 166.

- ^ Nollen: 29; cf. Gilliam: 60, Boyle and Bunie: 226–229.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 176–177; cf. Nollen: 29.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 178–182; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 238–240, 257; cf. Gilliam: 62–64, Duberman: 140–144.

- ^ Duberman: 151; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 262–263.

- ^ Oakley, Annie (1932-05-24). "The Theatre and Its People". Border Cities Star. p. 4.; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 253–254, Duberman: 161, Robeson 2001: 192–193.

- ^ Duberman: 161; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 258–259, Robeson 2001: 132, 194.

- ^ Sources are unclear on this point. Duberman: 145; cf. Robeson 2001: 182.

- ^ Duberman: 162–163; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 262–263, Robeson 2001: 194–196.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 195–200; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 267–268, Duberman: 166.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 271–272; cf. Duberman: 167, Robeson 2001: 203–204.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 271–273; cf. Duberman: 167, Robeson 2001: 204.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 273–274; cf. Duberman: 167, Robeson 2001: 204.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 269–271.

- ^ Nollen: 41–42; cf. Robeson 2001: 207; Duberman: 168–169.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 275–279; cf. Duberman: 167–168.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 285–287.

- ^ "'Black Greatness'". The Border Cities Star. 1933-09-08. p. 4.; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 284–285; cf. Duberman: 169–170.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 285–286.

- ^ Boyle and Bunie: 284–285.

- ^ . Boyle and Bunie: 288; cf. Duberman: 136–137, 170, 623; A Tribute to Paul Robeson.

- ^ The rationale for Robeson's sudden interest in African history is viewed as inexplicable by one of his biographers (Martin Bauml Duberman p. ?), and no biographers have stated an explanation, for what Duberman terms as a "sudden interest"; cf. Cameron: p. 285.

- ^ a b Nollen: 52.

- ^ Nollen: 45.

- ^ Duberman: 182–185.

- ^ Smith, Ronald A. (Summer, 1979). "The Paul Robeson—Jackie Robinson Saga and a Political Collision". Journal of Sport History. 6 (2).

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); cf. Duberman: 184–185, 628–629. - ^ Foner 1978: 94–96 (Smith, Vern (1935-01-15). "'I am at Home,' Says Robeson at Reception in Soviet Union", Daily Worker)

- ^ Nollen: 53–55.

- ^ Nollen: 53; cf. Duberman 178–182.

- ^ Rotha, Paul (1935, Spring). "Sanders on the River". Cinema Quarterly. 3 (3): 175–176.

You may, like me, feel embarrassed for Robeson. To portray on the public screen your own race as a smiling but cunning rogue, as clay in a woman's hands (especially when she is of the sophisticated American Brand), as toady to the white man is no small feat.... It is important to remember that the multitudes of this country [Britain] who see Africa in this film, are being encouraged to believe this fudge is real. It is a disturbing thought. To exploit the past is the historian's loss. To exploit the present means in this case, the disgrace of a Continent.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); cf. Duberman: 180–182; contra: "Leicester Square Theatre: Sanders of the River", The Times: p. 12. 1935-04-03. - ^ Low: 257; cf. Duberman: 181–182.

- ^ Low: 170–171.

- ^ Sources are unclear if Robeson unilaterally took the final product of the film as insulting, or if his distaste of the film was abetted by criticism of the film. Nollen: 53; cf. Duberman: 182.

- ^ Foner 1978: 104–105

- ^ Robeson Jr.: 279-280.

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0028282/

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0028249/

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0028629/

- ^ "Africa Sings". Villon Films. Retrieved 2012-07-10.

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0029081/

- ^ "Most Popular Stars of 1937: Choice of British Public". The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954). Hobart, Tas.: National Library of Australia. 12 February 1938. p. 5. Retrieved 25 April 2012.; cf. Richards, Jeffrey: 18.

- ^ Robeson 1958: ?; cf. Robeson 1981: 38.

- ^ Robeson 2001: 292; cf. Boyle and Bunie: 375–378.

- ^ Glazer defines it as a change from a "..lyric of defeat into a rallying cry." Glazer: 167; cf. Roberson 2001: 293, Boyle and Bunie: 381, Lennox 2011: 124, Robeson 1981: 37, Hopkins: 313 "At Manchester Free Trade Hall on September 28, 1938, Paul Robeson led in singing the famous verses of ...[the hymn] Jerusalem...This suggests a very different spirit from that which the historian Gareth Stedman Jones found a generation earlier. He had written of workers who buried their millennial dreams and adopted a defensive strategy to fend off the aggressions of employers of the 1890s. ...For those who sang Jerusalem then, it was not as a battle-cry but as a hymn. For those caught up in the passion play of Spain, and still eager to recapture lost ideological positions it had become a battle cry."

- ^ Duberman: 222.

- ^ "Paul Robeson at the Unity Theater", Daily Express June 20, 1938.

- ^ "Paul Robeson". Coalfield Web Materials. University of Swansea. 2002.

- ^ Boyle: 396.

- ^ "Spanish Relief Efforts: Albert Hall Meeting £1,000 Collected for Children". The Manchester Guardian. 1937–06–25. p. 6.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); cf. Brown: 77, Robeson 2010: 372. - ^ Beeves: 356.

- ^ Weyden: 433–434.

- ^ Beevor: 356; cf. Eby: 279–280, Landis: 245-246

- ^ Wyden: 433–434.

- ^ "India's Struggle for Freedon{{sic}}: Mr. Nehru on Imperialism and Fascism". The Guardian. 1938–06–28.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); cf. Duberman:225 - ^ http://williamlkatz.com/paul-robeson-anti-fascist-crusade

- ^ "Robeson Joins London Workers' Theatre". Chicago Defender. 1938–07–02. p. 24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); cf. Nollen: 122 - ^ Price: 8–9; cf. Collier's ??

- ^ Duberman: 236–238.

- ^ Bourne, Stephen. "The Proud Valley". Edinburgh Film Guide. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ FBI record, "Paul Robeson". FBI 100-25857, New York, December 8, 1942.

- ^ Nollen: 137.

- ^ Duberman: 259–261.

- ^ Lustiger: 125–127.

- ^ Foner, Henry (2002). "Foreword". In Dorinson, Joseph; Pencak, William (eds.). Paul Robeson: Essays on His Life and Legacy. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 1. ISBN 0-7864-2163-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "Paul Robeson as Othello". 2010-07-29.

- ^ NAACP Spingarn Medal

- ^ Robinson, Greg (March 13, 2008). "Paul Robeson and Japanese Americans, 1942–1949". j.

- ^ Nollen: 157

- ^ "Group Confers with Truman on Lynching". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 1946-09-24. p. 2.

- ^ Nollen: 157–156.

- ^ Duberman: 241.

- ^ Cornell, Douglas B. (1947-12-05). "Attorney General's List of 'Subversive Groups' is Derided by Solon". The Modesto Bee. p. 1.; cf. Goldstein 2008, p. 62, 66, 88

- ^ "Wallace Rally Presents Paul Robeson,Marshall". Atlanta Daily World. 1948-06-22. p. 3. cf. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution 06/21/1948, Macon-The Central City 06/24/1948 Atlanta Daily World, p. 2

- ^ a b Duberman: 249–250.

- ^ Robeson 2010: 137.

- ^ Robeson 2010: 138.

- ^ Foner 1978: 197–198

- ^ Robeson 2010: 142–143; cf. Foner 1978: 197–198,

- ^ Robeson 2010: 142–143; cf. Duberman: 342–345, 687.

- ^ Robeson 2010: 142–143; cf. Foner 1978: 197–198, Seton 1958: 179, Interview with Paul Robeson, Jnr.

- ^ "Studs Terkel, Paul Robeson - Speak of Me As I Am, BBC, 1998"

- ^ Wilkins: 200–205.

- ^ Duberman: 352–353.

- ^ a b Lustiger: 210–211.

- ^ a b McConnell: 348.

- ^ Duberman: 353–354.

- ^ Duberman: 358–360; cf. Robinson 1972: 94–98.

- ^ a b Duberman: 361–362; cf. Robinson 1972: 94–98.

- ^ Duberman: 364; cf: Robeson 1981: 181

- ^ Duberman; 364-370; cf. Robeson 1981: 181

- ^ Robeson: 373–374.

- ^ LA Times: Jan 1, 1950, p. ?

- ^ Brown 1998: 162; cf. Robeson 1971: 5, Walsh only listed a ten man All-American team for the 1917 team and he lists no team due to World War I. Walsh: 1949: 16–18, 32, The information in the book was compiled by information from the colleges, "...but many deserving names are missing entirely from the pages of [the] book because ... their alma mater was unable to provide them. - Glenn S. Warner" Walsh: 6, The Rutgers University list was presented to Walsh by Gordon A. McCoy, Director of Publicity for Rutgers, and although this list says that Rutgers had two All-Americans at the time of the publishing of the book, the book only lists the other All-American and does not list Robeson as being an All-American. Walsh: 684

- ^ Walsh: 689

- ^ "Mrs. Roosevelt sees a 'Misunderstanding'". New York Times. 1950-03-15.

- ^ "Protests Block Robeson as Guest On Mrs. Roosevelt's TV Program". New York Times. 1950-03-14. p. 1.

- ^ Wright 1975: 97.

- ^ Duberman: 388–389.

- ^ Von Eschen: 181-185

- ^ Robert Alan, "Paul Robeson - the Lost Shepherd". The Crisis, November 1951 pp. 569–573.

- ^ Duberman 1988: 396

- ^ Foner, Henry 2001 ? : 112–115 ?

- ^ Von Eschen: 127

- ^ Duberman: 396; cf. Foner, Henry 2001? : 112–115

- ^ Duberman: 397–398.

- ^ "Paul Robeson is Awarded Stalin Prize". The News and Courier. 1952-12-22. p. 6.

- ^ "Post Robeson Gets Stalin Peace Prize". The Victoria Advocate. 1953-09-25. p. 5.

- ^ Foner 1978: 347–349.

- ^ Duberman: 354.

- ^ Foner 1978: 236–241

- ^ Duberman, p. 400.

- ^ Duberman p. 411.

- ^ Howard, Tony (2009-01-29). "Showcase: Let Robeson Sing". University of Warwick.

- ^ Duberman 1988: 437

- ^ Barry Finger, "Paul Robeson: A Flawed Martyr", in: New Politics Vol. 7 No. 1 (Summer 1998)

- ^ Robeson 1978: 3–8.

- ^ Duberman: 463

- ^ "British Give Singer Paul Robeson Hero's Welcome". The Modesto Bee. 1958-07-11.

- ^ Duberman: 469

- ^ "The International Children Center Artek Timeline – the 1950s". Artek.org. Retrieved 2012-07-10.

- ^ Duberman: 471

- ^ Duberman: 472.

- ^ Robeson 1981: 218.

- ^ White, Michael (1 June 2000). "Obituary: Andrew Faulds". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Duberman: 487–491.

- ^ Curthoys: 171.

- ^ Duberman: 489

- ^ Curthoys: 168 ; cf. Duberman: 489.

- ^ Foner 1978 : 470–471.

- ^ Curthoys: 164, 173–175: cf. Duberman: 490.

- ^ Curthoys: 175–177; cf. Duberman

- ^ Curthoys: 171–172.

- ^ Curthoys: ? ; cf. Duberman: 490–491.

- ^ Curthoys: 178–180; cf. Duberman 491.

- ^ Robeson 2010: 309

- ^ a b c Duberman: 498–499.

- ^ Nollen: 180

- ^ a b c Radio broadcast presented by Amy Goodman, Did the U.S. Government Drug Paul Robeson? (Part 1). Democracy Now (July 1, 1999) Did the U.S. Government Drug Paul Robeson? (Part 2). Democracy Now (July 6, 1999). Cite error: The named reference "Democracy Now" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Duberman: 563–564.

- ^ Duberman: 438–442.

- ^ Robeson, Paul Jr. (1999-12-20). "Time Out: The Paul Robeson Files". The Nation. 269 (21): 9.

- ^ Duberman: 735–736.

- ^ Nollen: 180–181.

- ^ Travis, Alan (2003-03-06). "Paul Robeson was tracked by MI5". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited.; cf. Western Mail, [1]

- ^ Duberman: 509

- ^ Nollen: 182

- ^ Duberman: 516–518.

- ^ a b Duberman: 537.

- ^ Robeson, Jr. 2010: 346

- ^ Farmer: 297–298.

- ^ Duberman: 162–163.

- ^ Robeson 1981: 235–237.

- ^ a b Bell: ?

- ^ Duberman: 542–543.

- ^ a b Robeson 1978: 6.

- ^ Brooks Atkinson, Broadway

- ^ a b Duberman: 516.

- ^ Brown 1998: 161

- ^ "James Earl Jones Wins 2011 Paul Robeson Award".

- ^ "Died". Time. February 2, 1976.; Duberman: 548

- ^ Robeson 1981: 236–237

- ^ a b Duberman: 549

- ^ Hoggard, Bishop J. Clinton. "Eulogy". The Paul Robeson Foundation.

- ^ Tapley, Mel (1976-01-31). "Every Artist Must Know Where He Stands". New York Amsterdam News. pp. D10+.; cf. Duberman: 549, 763

- ^ "List of National Historic Landmarks by State" (PDF), National Historic Landmarks Program, 2012-01-03, p. 71

- ^ "Paul Robeson Galleries".; cf. Paul Robeson Library, [2]The Paul Robeson Cultural Center, [3]

- ^ O'Malley, Padraig. "1978". Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory.

- ^ Armour, Nancy (1995-08-26). "Brown, Robeson inducted into college football hall". The Day. Reid MacCluggage. pp. C6.

- ^ "From the Valley of Obscurity, Robeson's Baritone Rings Out; 22 Years After His Death, Actor-Activist Gets a Grammy". The New York Times. February 25, 1998.

- ^ "The Paul Robeson centennial". Ebony. 53 (7): 110–114. 1998-05-01.; cf. Lorenzo Dow Turner

- ^ Hold, Hon. Rush D. (20 Jan 2004). "Unveiling United States Postage Stamp in Honor of Paul Robeson" (PDF). United States Government Printing Office.

- ^ Finkelman: 363; cf. Dorinson: 74

- ^ Miller, Patrick B. (2004). "Muscular assimilationism : sport and the paradoxes of racial reform". Race and Sport. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. pp. 149–150. ISBN 1-57806-657-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Duberman: 81

- ^ Nollen ?

- ^ Duberman: 90; cf. Bogle 2001: 100

- ^ Von Eschen: 185

- ^ Reva Klein, "Citizenship: Let Paul Robeson Sing" The Times Educational Supplement, October 26, 2001

- ^ Faingold, Noma (June 19, 1998). "Centennial of Birth Marked Here—Paul Robeson: Forgotten Hero of Jews, African-Americans". j.

- ^ "Paul Robeson zu Gast Unter den Linden — Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin" (in Template:De icon). Hu-berlin.de.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Duberman: 557

- ^ Von Eschen: 1-2

- ^ Balaji: 430–432.

- ^ Richards, Larry:231

References

Primary materials

- Dent, Roberta Yancy, with Marilyn Robeson and Paul Robeson, Jr. eds. Paul Robeson, Tributes, Selected Writings. New York: The Archives, 1976. OCLC 2507933.

- Foner, Philip S., ed. Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings, Speeches, Interviews, 1918–1974. Larchmont: Brunner/Mazel, 1978. ISBN 0-87630-179-0

- Robeson, Paul Leroy (1919-06-10). "The New Idealism". The Targum 50, 1918–1919: 570–1.

- Robeson, Paul; with Brown, Lloyd L. (1998). Here I Stand. (2 ed.). Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-6445-9

- Robeson, Paul (2000). "An Actor's Wanderings and Hopes". The Messenger Reader. New York: The Modern Library. pp. 292–293. ISBN 0-375-75539-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)

Biographies

- Boyle, Sheila Tully, and Andrew Bunie (2001). Paul Robeson: The Years of Promise and Achievement. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-55849-149-X

- Brown, Lloyd L. (1997). The Young Paul Robeson: On My Journey Now. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3178-1

- Duberman, Martin Bauml (1988). Paul Robeson. New York: New Press. ISBN 1-56584-288-X.

- Gilliam, Dorothy Butler (1976). Paul Robeson, All-American. Washington, D.C.: New Republic Books ISBN 0-915220-39-3

- Hoyt, Edwin P. (1968). Paul Robeson: The American Othello. Cleveland: The World Publishing Company.

- Ramdin, Ron (1987). Paul Robeson, The Man and His Mission. London: Peter Owen. ISBN 0-7206-0684-5

- Robeson, Eslanda (1930).Paul Robeson, Negro, London: Victor Gollancz Ltd.; 1st edition (1930) ASIN: B0006E8ML4

- Robeson Paul, Jr. (2001) The Undiscovered Paul Robeson, An Artist's Journey, 1898–1939. Wiley. eISBN 9780471151050

- Robeson Paul, Jr. (2010) The Undiscovered Paul Robeson, Quest for Freedom, 1939–1976. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-40973-1

- Seton, Marie (1958). Paul Robeson. London: Dennis Dobson.

Secondary materials

- Balaji, Murali (2007). The Professor and the Pupil: The Politics and Friendship of W. E. B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson. New York: Nation Books ISBN 1-56858-355-9

- Beevor, Anthony (2007). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. London: Phoenix. ISBN 9780753821657

- Bell, Charlotte Turner (1986). Paul Robeson's Last Days in Philadelphia Bryn Mawr: Dorrance Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 0-8059-3026-4

- Bogle, Donald (2001). Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films (4 ed.). New York: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-1267-X

- Cameron, Kenneth M. (1990-10-01). "Paul Robeson, Eddie Murphy, and the Film Text of 'Africa'". Text & Performance Quarterly. 10 (4): 282–293.