Lê Duẩn

Lê Duẩn | |

|---|---|

Le Duan in 1978 | |

| General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam | |

| In office 10 September 1960 – 10 July 1986 | |

| Preceded by | Hồ Chí Minh |

| Succeeded by | Trường Chinh |

| Secretary of the Central Military Commission of the Communist Party | |

| In office 1981–1984 | |

| Preceded by | Võ Nguyên Giáp |

| Succeeded by | Văn Tiến Dũng |

| Member of the Politburo | |

| In office 1957 – 10 July 1986 | |

| Member of the Secretariat | |

| In office 1956 – 10 July 1986 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Lê Văn Nhuận 7 April 1907 Quảng Trị province, French Indochina |

| Died | 10 July 1986 (aged 79) Hanoi, Socialist Republic of Vietnam |

| Nationality | Vietnamese |

| Political party | Communist Party of Vietnam |

Lê Duẩn (7 April 1907 – 10 July 1986) was a Vietnamese communist politician. He rose in the party hierarchy in the late 1950s, and was elected General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam (VCP) at the 3rd National Congress of the Workers Party of Vietnam. He continued Hồ Chí Minh's policy of ruling through collective leadership. From mid-1960s, when Hồ's health was failing, until his own death in 1986, he was the top decision-maker in Vietnam.

Born into a lower-class family in Quảng Trị province, French Indochina as Lê Văn Nhuận; little is known about Le Duan's family and childhood. He first came in contact with Marxist literature in the 1920s through his work as a railway clerk. Le Duan was a founding member of the Indochina Communist Party (the future Communist Party of Vietnam) in 1930. He was arrested in 1931, and was released in 1937. From 1937 to 1939 he worked himself up the party ladder; but he was rearrested in 1939, this time for fomenting an uprising in the South. Le Duan was released from jail following the successful communist-led August Revolution.

During the First Indochina War, Le Duan was an active communist cadre in the South. He headed the Central Office of South Vietnam, a Communist Party organ, from 1951 until 1954. During the 1950s Le Duan became increasingly aggressive towards the South and called for reunification through war. By the mid-to-late 1950s Le Duan had become the second-most powerful policy-maker within the Communist Party, eclipsing former party First Secretary Trường Chinh. By 1960, at the 3rd National Congress, he had become General Secretary and, because of his office, officially become the second-most powerful party member, after Hồ Chí Minh, the party chairman. Throughout the 1960s Hồ's health began to decline, and Le Duan took over more of his responsibilities. On 2 September 1969, Hồ died and Le Duan became the most powerful decision-maker in Vietnam.

Throughout the Vietnam War, Le Duan had held an aggressive posture against the Americans. Attack, rather than a defensive strategy, was to be the key to victory. When Vietnam finally won the war in 1975, Le Duan and his associates were overly optimistic about the future. The Second Five-Year Plan (1976–1980) was a failure, and after it the Vietnamese economy was in dire crisis. To make matters worse, Vietnam was headed by a gerontocracy (in which the rulers are much older than the population average). Vietnam became internationally isolated during Le Duan's rule; the country had invaded Kampuchea and ousted Pol Pot from power (which was internationally condemned), engaged in a short war with China and had become dependent on Soviet economic aid. Le Duan died in 1986 and was succeeded by Trường Chinh in July 1986; Trường Chinh was in turn succeeded by Nguyễn Văn Linh in December later that year.

Early life and career

Le Duan was born in Quảng Trị province on 7 April 1907[1] (although some sources cite 1908)[2] as Lê Văn Nhuận.[3] Little is known about Le Duan's family and youth.[2] The son of a railway clerk[4], he became active in revolutionary politics early in his life. He received a French colonial education before he began working as a clerk for the Vietnam Railway Company in Hanoi during the 1920s.[2] Through his job, he came into contact with several communists.[5] It was in this period he became a keen supporter of Marxism.[6]

Le Duan became a member of the Revolutionary Youth League in 1928.[7] He was one of the cofounders of the Indochina Communist Party, which was established in 1930. His activities in the newly-established Communist Party did not last long; he was arrested in 1931. He was released six years later, in 1937. From 1937 to 1939 he worked his way up the party ladder, and at the 2nd National Congress of the Indochina Communist Party, he was elected to its Central Committee.[8] He was arrested the following year for trying to foment an uprising in South Vietnam, but was released shortly after the 1945 August Revolution, the event in which the Indochinese Communist Party took power. Following his release from jail, he became a trusted associate of Hồ Chí Minh, a leading Vietnamese communist.[9]

During the First Indochina War Le Duan served as the Secretary of the Regional Committee of South Vietnam, at first in Cochin China in 1946, but was reassigned to head the Central Office of South Vietnam from 1951 until 1954. The Viet Minh's stance in the South became increasingly tenuous by the early-to-mid 1950s, and in 1953 Le Duan was replaced by his deputy Lê Đức Thọ, and returned to North Vietnam. In the aftermath of the 1954 Geneva Accords, which indirectly decided to split Vietnam into North and South, Le Duan was responsible for reorganising the combatants who had fought in South and Central Vietnam.[9] In 1956, Le Duan wrote a thesis called "The Road to the South", which called for a violent revolution in South Vietnam against the United States to achieve reunification. The thesis was accepted as a blueprint for action by the CPV Central Committee at its 11th Plenum in 1956. Although "The Road to the South" was formally implemented, in practice its implementation was postponed to 1959.[10]

Throughout 1956, the party had been split by factional rivalry between party boss Trường Chinh and President Hồ, who was supported by Võ Nguyên Giáp. This rivalry focused on the issue of land reform in North Vietnam. As Le Duan was identified with neither of these factions, neither objected when he began performing the duties of First Secretary (head of the Communist Party) on behalf of Hồ in late 1956. At the May Day parade in 1957, Trường Chinh was still seated as the second most powerful figure within the communist system. Le Duan was gradually able to place his supporters, notably Lê Ðức Thọ, in top positions and outmaneuver his rivals. He visited Moscow in November 1957 and received the green light for his war plans regarding the South.[11] By 1958, Le Duan was ranked as second only to Hồ in the party hierarchy, although Chinh remained powerful. Le Duan was a party man, and throughout his life, he would never hold a governmental post.[12]

In December 1957, Hồ told the 13th Plenary Session of a "dual revolution"; Chinh became responsible for the socialist transformation of North Vietnam, while Le Duan focused on planning the offensive in South Vietnam.[12] Le Duan was ordered by the Politburo in August 1956 to guide the revolutionary struggle in South Vietnam. The same month he traveled from U Minh to Ben Tre, and instructed the South Vietnamese communists to stop fighting in the name of religious sects. He entrusted Sau Dương to write an ideological thesis on the proper conduct of military propaganda.[10] Le Duan made a brief, secret visit to South Vietnam in 1958, writing a report, The Path to Revolution in the South, in which he stated that the North Vietnamese had to do more to assist the southern communists against the South Vietnamese government.[13] The Central Committee decided to initiate the revolution in South Vietnam in January 1959.[14]

Shortly after writing The Road to the South, Le Duan was appointed to the Secretariat in 1956, and in 1957, he was given a seat in the Politburo. Le Duan was informally chosen as the party's First Secretary (later known as the General Secretary) by Hồ in 1959, at the January plenum of the Central Committee, and was elected to the post de jure at the 3rd National Congress.[9] Le Duan was not Hồ's original choice for First Secretary according to Bùi Tín; his preferred candidate was Võ Nguyên Giáp, but since Le Duan was supported by the influential Lê Đức Thọ, the Head of the Party Organisational Department, Le Duan was picked for the post. Le Duan was considered a safe choice because of his time in prison during French rule, his thesis The Road to the South and his strong belief in Vietnamese reunification.[15] Hoàng Văn Hoan claimed, after being sent into exile, that the 3rd National Congress, which elected Le Duan as First Secretary, purged several party members; this may be true, three former ambassadors lost their seats in the Central Committee at the 3rd National Congress.[16]

General Secretaryship

Political infighting and power

Le Duan was officially named party leader in 1960, leaving Hồ a public figure for the Vietnamese rather than actually governing the country. Hồ maintained much influence in the government: Le Duan, Tố Hữu, Trường Chinh, and Phạm Văn Đồng would often share dinner with him. Later, throughout and after the war, all of them remained key figures in Vietnam. In 1963, Hồ purportedly corresponded with South Vietnamese President Diệm in the hope of achieving a negotiated peace.[17] Together with Lê Đức Thọ, Head of the Party Organisational Department, and Nguyễn Chí Thanh, a military general, Le Duan tried to monopolise the decision-making process – this became even more evident following Hồ's death.[18] Beginning in 1964, Hồ's health began to fail and Le Duan, as Hồ's second-man, took on more day-to-day decision-making responsibilities.[19] There are those who claim that by 1965, Hồ and Le Duan were enemies, and that "for all intents and purposes" Le Duan had managed to sideline Hồ.[20] Le Duan, Lê Đức Thọ and Phạm Hùng "progressively tried to neutralise Hồ Chí Minh" and Phạm Văn Đồng.[20]

By the late-1960s, Hồ's position within the Vietnamese leadership had been considerably weakened due to his declining health. While Hồ was still consulted on important decisions, it was Le Duan who was the dominant driving force within the party. When Hồ died on 2 September 1969, the collective leadership he had espoused continued, but Le Duan became its first amongst equals.[21] The first resolution from the Central Committee, in response to Hồ's death, pledged to uphold the collective leadership. Le Duan chaired the committee responsible for Hồ's funeral. At the funeral, Le Duan gave the last tribute speech to Hồ.[22]

The party leadership had, from the beginning, been split into factions: one pro-Soviet, one pro-Chinese and one moderate.[23] Under Hồ the party had followed a policy of neutrality between the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China in the aftermath of the Sino–Soviet split. This line was kept until 1975, when the war ended. In the aftermath of the war, a power struggle began between the pro-Soviet and pro-Chinese factions; the pro-Soviet led by Le Duan won. Le Duan and Lê Đức Thọ, former rivals, formed a coalition within the Party leadership; together they initiated a purge against the pro-Chinese faction, the first two victims being Hoàng Văn Hoan and Chu Văn Tấn. While the Politburo was a collective decision-making organ, which decided on issues through the support of a majority, Le Duan, through his post as General Secretary, was the most powerful figure within the Politburo, and able to amass power thanks to his alliances with Lê Đức Thọ, Trần Quốc Hoàn and Võ Nguyên Giáp.[24] Together with Lê Đức Thọ, Le Duan controlled personnel appointment in the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the State Planning Commission, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the General Political Directorate of the Vietnam People's Army (VPA), the General Logistics Department of the VPA, and the Ministry of Transport.[25]

To strengthen their hold on power, Le Duan and Lê Đức Thọ enforced certain nepotistic policies – nepotism being a system where favor is granted to relatives regardless of merit. For instance Lê Đức Thọ's brother, Đinh Đức Thiện was appointed Minister of Communications and Transport; in April 1982 Đồng Sỹ Nguyên, a protégé of Le Duan, became Minister of Transport.[26] Mai Chí Thọ, brother of Lê Đức Thọ, was Chairman of the People's Committee of Hồ Chí Minh City (equivalent to a Mayor) from 1978 to 1985. Several people, related to Le Duan by blood, were appointed to the propaganda and cultural sector of the state. However, most of the leadership were not relatives of Le Duan or Lê Đức Thọ, for instance Phạm Hùng held the post of Minister of Home Affairs.[27]

Vietnam War

At the 3rd National Congress, held in 1960, Le Duan called for the establishment of a South Vietnamese people's front.[28] The Central Committee responded to Le Duan's call in September 1960, and supported the establishment of the front. In a statement the Central Committee said, "The common task of the Vietnamese revolution at present is to accelerate the socialist revolution in North Vietnam whilst at the same time stepping up the National People's Democratic Revolution in South Vietnam."[29] On 20 December 1960, three months later, the National Front for the Liberation of the South, better known as Việt Cộng, was established. Le Duan claimed that the Việt Cộng would "rally 'all patriotic forces' to overthrow the Diệm government [in the South] and thus ensure 'conditions for the peaceful reunification of the Fatherland'".[29]

After the Sino–Soviet split, the Vietnamese communist leadership became divided into two factions, pro-China and pro-Soviet; Le Duan (at the beginning) was labeled pro-China, because of his hawkish policies towards South Vietnam. Later, in the post-war era, he was referred to as pro-Soviet. From 1956–63, Le Duan played a moderating role between the two factions, but with the death of the South Vietnamese leader Ngô Đình Diệm and the Gulf of Tonkin incident, he became considerably more radical.[19] The Chinese continued to support them throughout the war, with Liu Shaoqi, the Chairman of the People's Republic of China, stating in 1965 "it is our policy that we will do our best to support you."[30] Unlike Hồ, who wanted a peaceful resolution to the conflict, Le Duan was far more aggressive. He wanted, in his own words, "final victory". He dismissed Hồ's position, as did the majority of the CPV Politburo members. Le Duan dismissed Hồ for being "naive".[31] When Hồ called for the establishment of a neutral South Vietnamese state in 1963, Le Duan responded by making overtures to the Chinese, who rejected the Soviet position of peaceful coexistence.[32]

With the increased involvement of the United States military in the Vietnam War in 1965, the strategy against the South Vietnamese Government was forced to change. As Le Duan noted in a letter to Nguyễn Chí Thanh, the war would become "fiercer and longer".[33] He believed the fundamentals of the conflict had not changed; the South Vietnamese regime's unpopularity remained its "Achilles heel"[33] and he continued to believe victory could be achieved through a combination of uprising against the South Vietnamese regime and a communist offensive against it. The communist commanders in the South were to remain passive throughout the conflict, and were to restrict large attacks on the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), but instead focus on many small attacks which would demoralize the ARVN. The military had to keep the initiative in the conflict; Le Duan believed this to be a key to victory. He dismissed the possibility of an attack against North Vietnam by American forces, claiming that an attack on North Vietnam would be an attack on the socialist camp.[33]

By July 1974, the Vietnamese leadership had decided to set the victory year to 1975, instead of 1976 as originally planned, because they believed an earlier Vietnamese unification would put Vietnam in a stronger position against Chinese and Soviet influence in the region.[34] In his victory speech, Le Duan stated: "Our party is the unique and single leader that organised, controlled, and governed the entire struggle of the Vietnamese people from the first day of the revolution."[35] In his speech he congratulated the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (PRGRSV), the underground South Vietnamese government established in 1969, for liberating South Vietnam from imperialism. PRGRSV-ruled South Vietnam did not last long however, and in 1976 Vietnam was reunified and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam was established.[36] Le Duan instituted a purge of South Vietnamese who had collaborated with the Americans during the war; over one million people were consigned to prison camps.[37]

Economy

Having won the war, and defeated South Vietnam, the mood in April 1975 was optimistic. As one Central Committee member put it, "Now nothing more can happen. The problems we face now are trifles compared to those in the past."[38] Le Duan promised the Vietnamese people in 1976 that each family would own a radio set, refrigerator and TV within ten years; he seemed to believe he could easily integrate the South Vietnamese consumer society with industrial North Vietnam.[39] The 4th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam, held in December 1976, declared Vietnam would complete its socialist transformation within twenty years. This optimism proved unfounded; in the next decades Vietnam staggered from one financial crisis to another. Vietnam developed little during the war years; industry was nearly non-existent in both North and South, and both countries were dependent on foreign charity. To make matters worse, agriculture had been the main economic activity before the war, and its infrastructure had been badly damaged.[40] The rude awakening began when the Soviet Union reduced its economic aid to Vietnam, when the United States refused give Vietnam a promised three million dollars, and the extent of war damage became apparent. In the South there were roughly 20,000 bomb craters, 10 million refugees, 362,000 war invalids, 1,000,000 widows, 880,000 orphans, 250,000 drug addicts, 300,000 prostitutes, and 3 million unemployed. About this time a split occurred in the Communist Party between those favoring the existing system of state control and a central planned economy, and those who wanted to reform the system.[41]

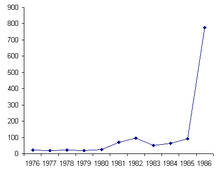

Until the 6th plenum of the Central Committee of the 4th National Congress, the conservative approach to economics prevailed. The plenum condemned the conservative way of ruling, and claimed that from then on the economy should be governed by "objective laws". The role of the plan and the market was openly discussed for the first time, and the roles of the family and the private economy were enhanced, and certain market prices were officially supported by the Party. At the beginning these changes had little practical effect on the economy; it may have been due to opposition by the conservatives and the general confusion amongst lower level cadres. From 1981–1984, agricultural production grew substantially, but the government did not use this opportunity to increase production of such crucial farm inputs as fertilizer, pesticides, and fuel, nor of consumer goods. By the end of Le Duan's rule, from 1985–1986, inflation had reached a level where rational economic policy-making was very difficult.[42]

The main goals of the Second Five-Year Plan (1976–1980), which was initiated at the 4th National Congress, were as follows;[43]

- "Concentrate the forces of the whole country to achieve a leap forward in agriculture; vigorously develop light industry"

- "[T]urn to full account existing heavy industry capacity and build many new industrial installations, especially in the machine industry, so as to support primary agriculture and light industry"

- "[V]irtually complete socialist transformation in the South"

The Vietnamese leadership expected to reach these targets with economic aid from the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) and loans from international agencies of the capitalist world. The 4th National Congress made it clear that agriculture would be socialised; however, during the Second Five-Year Plan the socialisation measures went so badly that Võ Chí Công, a Politburo member and Chairman of the Committee for the Socialist Transformation of Agriculture, claimed it would be impossible to meet the targets set by the plan by 1980. An estimated 10,000 out of 13,246 socialist cooperatives, established during the plan, had collapsed in the South by 1980.[44] Lê Thanh Nghị, a member of the Politburo, accused lower-level cadres for the failure of the socialist transformation of agriculture. The collectivisation process led to an abrupt drop in food production in 1977 and 1978 and, because of it, the 6th Plenum of the Central Committee decided to overhaul the Party's agricultural policies completely.[45]

With regard to heavy industry, the leadership's position was muddled. In his Fourth Political Report Le Duan stated that, during the transitional period to socialism, priority would be given to heavy industry "on the basis of developing agriculture and light industry". In another section of the report, Le Duan stated that light industry would be prioritised ahead of heavy industry. The position of Phạm Văn Đồng, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers (the head of government), was just as muddled as Le Duan's.[45] In practice heavy industry was always prioritised under Le Duan, the percentage of state investment in heavy industry was 21.4 in the Second Five-Year Plan and 29.7 percent in the Third Five-Year Plan (1981–1985), in contrast to light industry, which only received 10.5 and 11.5, respectively. From 1976 to 1978 industry grew, but from 1979 to 1980 industrial production fell substantially because the Party's policy of socialist transformation and other factors, such as poor management. During the Second Five-Year Plan industry grew just 0.1 percent. The 6th Plenum of the Central Committee criticised the policy that the state had to own everything.[46] Heavy industry would be prioritized throughout Le Duan's rule, with him stating that the country had to get a "firm grip on socialist industrialisation", and claiming it was the principal task of the transitional period.[47]

In 1976, Le Duan promised the Vietnamese people an improved standard of living in the next five to ten years. This did not happen. In 1976 per capita income stood at $101; it decreased to $91 in 1980, and then increased to $99 by 1982, according to figures by the United Nations. Phạm Văn Đồng admitted the failure of the Vietnamese leadership, and said that per capita income "had not increased compared to what it was ten years ago". Physical health declined, and malnutrition increased under Le Duan, according to the Ministry of Health.[48] According to the 14 April 1981 issue of The International Herald Tribune, an estimated 6,000,000 Vietnamese were suffering from malnutrition. Shortly thereafter, Vietnam's government requested aid from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.[49] Le Duan's regime's policies led to an abrupt decline in the standard of living; monthly per capita income in the North had declined from $81.6 in 1976 to $57.8 in 1980.[50]

Before the 5th Plenum of the Central Committee, Le Duan believed that Vietnam was in a perilous position, although no talk of reforms occurred at that plenum.[51] Beginning in 1979, Le Duan acknowledged that mistakes had been made by the national Party and State leadership in the economic sphere.[52] The reforms enacted by the 6th Plenum of the Central Committee was given the official support of Le Duan at the 5th National Congress (1982). Le Duan talked about the need to strengthened both the central planned economy and the local economy at once.[53] In his report to the 5th National Congress, Le Duan admitted that the Second Five-Year Plan had been a failure economically.[54]

Foreign relations

Relations with the Eastern Bloc

Le Duan visited the Soviet Union in October 1975. The result of the visit was an official communique, which stated that the Soviets would send qualified experts to the country to educate and train economic, scientific, technical and cultural personnel. The Soviet Union gave Vietnam economic assistance, and supported several national economic projects. Vietnam was given money by the Soviet Union on the most favoured terms for its part in socialist construction. The communique stated that cooperation between Vietnam was within the "frameworks of multilateral cooperation of socialist countries." Such a statement would normally have meant membership in the COMECON, but Vietnam was still not a member. Before becoming a Soviet satellite state, the Vietnamese leadership tried to uphold their sovereignty; this they did by not becoming a member of COMECON immediately. Phạm Văn Đồng snubbed the Soviet ambassor to Vietnam during the anniversary of the October Revolution and rejected several key Soviet foreign policy views and goals.[55] Despite the continued pressure from the Soviets, who sent Mikhail Suslov as an attendee to the 4th National Congress, to become a member of the COMECON, Vietnam stood firm on sovereignty.[55] Immediately following the end of the war, Vietnam became a member of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, a move the Soviet Union opposed.[56]

Vietnam became a member of the COMECON in 1978, because the leadership had failed to get enough economic aid to fund the Second Five-Year Plan.[57] In 1978 Le Duan and Phạm Văn Đồng[58] signed a 25-year Treaty of Friendship and Mutual Cooperation with the Soviet Union.[57] Under Soviet protection, Vietnam invaded Kampuchea, then led by Pol Pot. In reaction to Vietnam's invasion of Kampuchea, China invaded Vietnam. During the war with China, Vietnam responded by leasing several bases to the Soviet Union, to protect their territory from China. The normalization of relations between the Soviet Union and China was a worst case scenario for the Vietnamese leadership; it was rumored that one of China's demands was the ending of Soviet assistance to Vietnam if normalization happened. Vietnam played the role of Asia's Cuba; it supported local revolutionary groups and was a national headquarters for Soviet communism. Vietnam supported the Soviet intervention in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, and received $3 million a day in military aid to act as the Soviet Union's southern flank against China.[59]

Le Duan's foreign policy was criticised by Hoàng Văn Hoan, who accused Le Duan of giving up Vietnam's sovereignty to the Soviet Union.[60] A Soviet delegation led by Vitaly Vorotnikov, a member of the Soviet Politburo, visited Vietnam during its National Day, the holiday which celebrated the establishment of North Vietnam in the aftermath of the August Revolution, and met Le Duan personally.[61] Le Duan attended the 27th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and later met with Mikhail Gorbachev during his vacation to the Soviet Union in the aftermath of the 27th Party Congress.[62] Nikolai Ryzhkov, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, and Anatoly Dobrynin represented the Soviet Union at Le Duan's funeral.[63]

Relations with China

During the Vietnam War, the Chinese claimed that the Soviet Union would betray Vietnam. Zhou Enlai, the Premier of the People's Republic of China, told Le Duan that the Soviet Union would lie to Vietnam to improve its relationship with the United States. According to Zhou Enlai, this Soviet policy was first enacted following Alexei Kosygin's departure from Vietnam in 1965. Le Duan did not support such a view, and at the 23rd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (which China boycotted) he referred to the Soviet Union as a "second motherland" to him. Because of his statement, China began to cut its aid to Vietnam immediately. According to the first secretary at the Soviet embassy to China, the Vietnamese saw the Chinese reprisals as an attack on them.[64] At the 45th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China (CPC), instead of a communique by Hồ Chí Minh, Phạm Văn Đồng and Le Duan as had happened at the 44th anniversary of the CPC, the Vietnamese Central Committee exchanged with the CPC Central Committee an official greeting, but without any signatures from top-level officials.[65]

Relations between the two countries further deteriorated during the rapprochement between China and the US. The Vietnamese, who were still fighting the Americans in South Vietnam, felt betrayed. At the CPV Politburo meeting on 16 July 1971, the Vietnamese agreed that Chinese policy towards the United States was like a "torpedo" directed against Vietnam.[66] Zhou Enlai was told by Phạm Văn Đồng and Le Duan that President of the United States Richard Nixon's, upcoming visit to China was "against the interests of Vietnam". Later, in November, Phạm asked the Chinese to rescind Nixon's visit; the Chinese refused. Because of China's policy towards the United States, the Vietnamese began to doubt China, and they tried to hide information about Vietnam's planned military offensive against South Vietnam. The Chinese–US rapprochement did not hurt Sino–Vietnamese relations in the long run, because the Soviet Union also had a rapprochement with the United States.[67]

Both Chinese and Vietnamese documents state that relations between them took a turn for the worse in 1973–75. A Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs document claimed that China pursued a policy which aimed to hamper the eventual reunification of Vietnam, while Chinese documents stated that the source of the conflict was Vietnamese policy towards the Spratley and the Paracel Islands. However, the core issue for the Chinese was to stop, or at least reduce, Vietnam's cooperation with the Soviet Union. Because of increasing Soviet–Vietnamese cooperation, China became increasingly ambivalent about a quick reunification of Vietnam.[68]

During Le Duan's visit to China in early June 1973, Zhou Enlai told him that Vietnam should adhere to the Paris Peace Accords. Following the signing, Lê Thanh Nghị stated that the direction of Vietnam's communism was directly linked to its relations with the Soviet Union. The Chinese opposed immediate reunification, and to that end, began making economic agreements with the Provisional Revolutionary (Communist) Government of South Vietnam (PRGSV). PRGSV head Nguyễn Hữu Thọ, in contrast to officials from North Vietnam, was treated well by the Chinese.[69] In contrast to their actual goals, such a policy hurt relations between China and North Vietnam further. From then on, China and Vietnam drifted further apart; even Chinese aid did not help improve relations between them.[69]

Lê Thanh, a Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers and Chairman of the State Planning Commission, visited China in August 1975 to seek aid; the visit was unsuccessful. Later, on 22–28 September, Le Duan and Le Duan Thanh visited China in a second attempt to get economic assistance from China. During the visit the Vietnamese wanted to assure the Chinese they were interested in maintaining good relations with both China and the Soviet Union. Deng Xiaoping, a Chinese official, stated that both superpowers acted as imperialists and sought hegemony. Le Duan in a speech to the Chinese, while he did not mention the Soviet Union by name, noted that Vietnam won the war against South Vietnam because of help from other socialist countries. Other socialist countries were a reference to the Soviet-aligned bloc. Two agreements were signed between China and Vietnam, but no non-refundable aid agreement was made.[70] The visit was a failure; no joint communique was issued, and Le Duan left China earlier than planned.[71] According to scholar Anne Gilks, the Sino–Vietnamese alliance effectively ended with the Fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975.[72] Relations with China further deteriorated in the aftermath of the 4th National Congress; several leading pro-Chinese communists were purged from the party.[16]

Le Duan visited China from 20–25 November 1977, after a visit to the Soviet Union to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the October Revolution. He visited China to seek aid. Hua Guofeng, the CPC Chairman, stated that Sino–Vietnamese relations had deteriorated because they held different principles. While Hua insisted that China could not help Vietnam because of its own economic difficulties, and differences in principals, Le Duan stated that the only difference between China and Vietnam was how they viewed the Soviet Union and the United States. Following his visit, China through Xinhua condemned COMECON, of which Vietnam was a member.[73] China halted all economic development projects between May and July 1978.[58] During this period total aid given by the Chinese to Vietnam amounted to $300 million.[74]

Sino–Vietnamese War

On 17 February 1979, the Chinese People's Liberation Army crossed the Vietnamese border, withdrawing on March 5 after a two-week campaign which devastated northern Vietnam and briefly threatened the Vietnamese capital, Hanoi. Both sides suffered relatively heavy losses, with Chinese casualties put at over 40,000 and Vietnamese casualties at over 20,000. Subsequent peace talks broke down in December 1979, and both China and Vietnam began a major build-up of forces along the border. Vietnam fortified its border towns and districts and stationed as many as 600,000 troops; China stationed approximately 400,000 troops on its side of the border. Sporadic fighting on the border occurred throughout the 1980s, and China threatened to launch another attack to force Vietnam's exit from Kampuchea.[75][76]

The Cambodian–Vietnamese War

The independent Kampuchean communist movement was established alongside the Vietnamese and Laotian in the aftermath of the dissolution of the Indochinese Communist Party in 1955. The Kampuchean communist movement was the weakest of the three. When the Vietnamese began formal military aid to the Khmer Rouge in 1970, the Khmer leadership remained skeptical. On the orders of Võ Chí Công two regiments were sent into Kampuchea, which helped to liberate northern Kampuchea. Võ Chí Công promised Ieng Sary, then in charge of Khmer Rouge activities in northeast Kampuchea, that Vietnamese troops would withdraw when the conflict had been won by the communist. The entry of Vietnamese troops, led many Vietnamese officials to believe that Khmer Rouge officials had begun "to fear something".[77] In a conversation with Phạm Hùng, Le Duan told him that despite some differences in opinions between the two communist organisations, the "authentic internationalism and attitude" of the sides would strengthen their party-to-party relations.[77] However, Le Duan by reading reports by Võ Chí Công, was probably informed that "authentic internationalism" in Kampuchea was in trouble.[77] At the time, the Vietnamese leadership hoped this situation would change, but privately they understood that the Kampuchean situation was different from the Lao situation.[77]

Since the seizing the power of Pol Pot and his supporters of the Kampuchean Communist Party (KCP) in 1973, KCP–VCP relations deteriorated sharply. North Vietnamese formations which were active in Kampuchea during the civil war were, since 1973, regularly attacked by their own allies.[78] While, by 1976, it looked like Kampuchea–Vietnam relations were normalizing, private suspicions within the respective leaderships grew.[79] The first anniversary of Khmer Rouge seizing of power was celebrated in Vietnam, with Le Duan, Tôn Đức Thắng, Trường Chinh and Phạm Văn Đồng sent messages congratulation the election of Pol Pot, Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea as premier, President of the Presidium, and President of the Assembly of the People's Representative.[80] In turn, KCP sent a congratulatory message to the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam on its seventh anniversary. On 21 September 1976 a Vietnamese women delegation was sent to Kampuchea, and the KCP sent a public greetings to the 4th National Congress.[81] During all of this, the Vietnamese leadership hoped that pro-Vietnamese elements would develop within the KCP leadership. When Kampuchean radio announced the resignation of Pol Pot, Le Duan and the Vietnamese leadership took it seriously.[82] During his meeting with the Soviet ambassador to Vietnam, Le Duan told him that Pol Pot and his brother-in-law Ieng Sary had been removed from the KCP leadership. This was a welcoming change to Vietnam, since the two had constituted a "pro-Chinese sect conducting a crude and severe policy."[78] Le Duan added that "these were bad people [the KCP leadership headed by Pol Pot]", but that Nuon Chea was "our man and is my personal friend."[78] However, all-out confrontation was not planned, and Le Duan still believed that state-to-state relations could improve. He further noted that Kampuchea would eventually become like Laos, a socialist state headed by the Lao People's Revolutionary Party (headed by Kaysone Phomvihane), which nurtured its relationship with Vietnam and the Soviet Union.[83]

On 30 April 1977 Democratic Kampuchea attacked several Vietnamese villages in An Giang province, the most notable being the Ba Chuc Massacre. The Vietnamese leadership was shocked by this unprovoked attack, but nevertheless decided to launch a counterattack.[83] However, Vietnam was still keen on improving relations, and when Pol Pot, on 27 September 1977, declared the existence of the KCP, the Vietnamese leadership sent a congratulatory note. In a conversation with the Soviet ambassador to Vietnam on 6 October 1977, Le Duan failed to adequately explain why the Kampuchean regime was acting the way it was.[84] He described the leadership "strongly nationalistic and under strong influence of Peking [China]."[85] Le Duan called Pol Pot a Trotskyist while claiming that Ieng Sary was "a fierce nationalist and pro-Chinese."[85] He, however, faulty believed that Nuon Chea and Son Sen harbored pro-Vietnamese views.[85]

"The Pol Pot–Ieng Sary clique have proved themselves to be the most disgusting murderers in the later half of this century. Who are behind these hangmen whose hands are smeared with the blood of the Kampuchean people, including the Cham, who have been almost wiped out as an ethnic group, the Viet, and the Hoa? This is no mystery to the world. The Pol Pot–Ieng Sary clique are only a cheap instrument of the bitterest enemy of peace and mankind. Their actions are leading to national suicide. This is genocide of a special type. Let us stop this self-genocide! Let us stop genocide at the hands of the Pol Pot–Ieng Sary clique!

On 31 December 1977 Democratic Kampuchea broke of relations with Vietnam, stating that the "aggressor forces" from Vietnam sent to Kampuchea had to be withdrawn.[87] This was needed to "restore the friendly atmosphere between the two countries."[87] While they were accusing Vietnam of aggression, the real problem all along was the Vietnamese leadership' plan, or ideal, of establishing a Vietnamese-dominated Indochinese Federation.[87] The Vietnamese troops, located only twenty-four miles from Phnom Phen, in Kampuchea withdrew from the country in January, taking with them thousand of prisoners and civilian refugees.[87] While the point of the Vietnamese attack had been to dampen the Kampuchean leadership's aggressive stance, it had in fact the opposite effect – the Kampuchean leadership treated it as a major victory over Vietnam.[88] The supposed victory was equaled with their victory over the Americans. Instead of negotiating with the Vietnamese, the Kampuchean did not respond to any diplomatic overtures, and began another attack on Vietnam.[89] With renewed Kampuchean attacks, the Vietnamese leadership began to promote a Kampuchean uprising against Pol Pot's rule.[86] However, with the fighting growing worse day-by-day, the Vietnamese leadership decided to launch an invasion of Democratic Kampuchea.[90]

On 15 June the VCP Politburo sent a request to the Soviet Union of allowing a delegation headed by Le Duan to meet with Leonid Brezhnev and the Soviet leadership in general. The request was sent by foreign minister Nguyễn Duy Trinh who stated that the situation on the ground was decided by "the war of Kampuchea against the SRV [the Socialist Republic of Vietnam]."[91] In the yes of Nguyễn Duy Trinh, the situation would only continue to further aggravate, so it was an "urgent necessity of carrying out timely consultations with the Soviet comrades."[91] In a meeting with the Soviet ambassador to Vietnam in September 1978, Le Duan said the VCP Politburo had set it goals "to solve fully this question [of Kampuchea] by the beginning of 1979."[92] Le Duan did not believe that China would retaliate because of the planned Vietnamese invasion, claiming that to do so, it had to send its military by sea to Kampuchea. However, they did attack in 1979, but not Vietnamese forces in Kampuchea, but Vietnam itself (see "Sino–Vietnamese War" section). He further claimed that Vietnam had little time, waiting any longer would mean a stronger institutionalized present for China in Kampuchea.[93] He further claimed that Vietnam had established nine battalions of Khmer deserters, and that Vietnam was seeking Sao Pheum to head these battalions. However, at this time, Sao Pheum had been dead for three months. Le Duan still believed that Nuon Chea was a friend of Vietnam, even if Nuon Chea had recently held a largely anti-Vietnamese speech in China.[93] However, these views and more would prove unfounded for; Nuon Chea and Son Sen would remain staunch Pol Pot supporters until the 1990s.[94]

Vietnam launched its invasion of Kampuchea on 25 December 1978, using 13 divisions, estimated at 150,000 soldiers well-supported by heavy artillery and air power. Initially, Kampuchea directly challenged Vietnam’s military might through conventional fighting methods, but this tactic resulted in the loss of half of the Kampuchean Revolutionary Army within two weeks. Heavy defeats on the battlefield prompted much of the Kampuchean leadership to evacuate towards the western region of the country. On 7 January 1979, the Vietnamese Army entered Phnom Penh along with members of the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation. On the following day, a pro-Vietnamese Kampuchean state, known as the People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK), was established, with Heng Samrin as the head of state and Pen Sovan as General Secretary of the Kampuchean People's Revolutionary Party. The establishment of the PRK led directly to the Sino-Vietnamese War, and Vietnam's war on anti-PRK elements in Kampuchea until 1989 when Vietnam withdrew its forces.[95]

Last years and death

By the time of the 5th National Congress, the ruling elite had turned into a virtual gerontocracy. The five most powerful Politburo members were all over the age of 70; Le Duan was 74, Trường Chinh was 75, Phạm Văn Đồng was 76, Phạm Hùng was 70 and Lê Đức Thọ was 72. Le Duan is believed to have been in bad health during this period; he had travelled to the Soviet Union on several occasions to receive medical treatment during the late-1970s and early 1980s. It was reported that Le Duan did not lead the party delegates of the 5th National Congress to the Hồ Chí Minh Mausoleum because of his deteriorating health. At the 5th National Congress Le Duan looked both feeble and old; he had problems reading his report to the Congress. It is said that Le Duan suffered a heart attack after the congress, and was flown to the Soviet Union for hospitalisation.[96] Le Duan remained general secretary until his death on 10 July 1986.[97]

Le Duan died of natural causes in Hanoi at age 79. He was succeeded by Trường Chinh. Chinh proved to be a temporary replacement, and at the 6th National Congress (held in December 1986) he was deposed and replaced by Nguyễn Văn Linh.[97]

Political beliefs

In many ways Le Duan was a nationalist, and during the war, he claimed that the "nation and socialism were one".[98] Since the Sino-Vietnamese War in 1979, Le Duan stressed the importance of building socialism politically, economically and culturally, and of defending the socialist fatherland itself.[99] Ideologically he was often referred to as a pragmatist.[98] He would often break with Marxism–Leninism and stress the uniqueness of Vietnam, as he did most notably in agriculture. Le Duan's own view of socialism was statist, highly centralised and managerial.[98]

In one of his own works, Le Duan talked about "the right of collective mastery", but in practice he opposed this. For instance, party cadres, who represented the peasants' demands for higher prices for their products at the National Congress, were criticised by Le Duan, whose ideas of collective mastery were conceived in a hierarchical top-down manner "Management by the state aims at ensuring the right of the masses to be the collective masters of the country. How then will the state manage its affairs so as to ensure this right of collective mastery?"[98] His answer to this problem was both managerial and statist.[100]

The concept "collective mastery", attributed to Le Duan, was featured in the 1980 Vietnamese Constitution as is the concept of "collective mastery" of society. The concept was Le Duan's version of popular sovereignty that advocated an active role for the people, so that they could become their own masters as well as masters of society, nature, and the nation. It stated that the people's collective mastery in all fields was assured by the state, and was implemented by permitting their participation in state affairs and in mass organisations. On paper, these organisations, to which almost all citizens belong, play an active role in government and have the right to introduce bills before the National Assembly.[101]

According to orthodox thinking, there were only two alternatives in agriculture, collective or private ownership of the land. Le Duan said that these two differences entailed a "struggle between the two roads –collective production and private production; large-scale socialist production and small scattered production."[102] This quote could easily have been taken as one from Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong or Trường Chinh in his radical years. Such a view had a direct impact on Vietnam. Since it was believed that collective ownership was the only alternative to capitalism, it was introduced without controversy by the country's leadership.[102]

Subcontracting of cooperatives to peasants became the norm by the late-1970s, and was legalised in 1981. For the conservatives this policy was similar to that of the New Economic Policy, a temporary break from the hardline socialist developmental strategy, in Lenin's Russia, and later, the Soviet Union. However, those who supported these reforms saw it as another way of implementing socialism in agriculture, which was justified by the ideological tenet of the "three interests". This was an important ideological innovation, and it broke with Le Duan's "two roads" theory, which said it was either collective or private ownership, and nothing in between.[102]

Le Duan made a departure from the Marxism–Leninism rationale when it came to practical policy, and stated that the country had to "carry out agricultural cooperation immediately, even before having built large industry."[103] While he acknowledged that his view was a break with that of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Vladimir Lenin, Le Duan insisted that Vietnam was in a unique situation; "It seems that no country so far in history has been in a situation such as ours. We must lead the peasantry and agriculture immediately to socialism, without waiting for a developed industry, though we know very well that without the strong impact of industry, agriculture cannot achieve large-scale production and new relations of agriculture cannot be consolidated... To proceed from small-scale production to large-scale production is a new one."[104] According to Le Duan the key to socialism was not mechanisation and industrialisation, but a new division of labour. He also believed that Cooperatives did not need to be autarkic, but rather "organically connected, through the process of production itself, with other cooperatives and with the state economic sector."[104] Vietnam could achieve this through state intervention and control, according to Lê. He saw the economy as one whole directed by the state, and not many parts intertwined.[104]

In his victory speech to the Vietnamese people in the aftermath of the 1976 parliamentary election, Le Duan talked about further perfecting the construction of socialism in the North by eliminating private ownership and the last vestiges of capitalism, and of the need to initiate a socialist transformation in the South. In the South the Party, according to Le Duan, would focus on abolishing the comprador bourgeoisie and the last "remnants of the feudal landlord classes". "Comprador bourgeoisie" was a Vietnamese communist term for the bourgeois classes, which made a living by financial dealings and through business transactions with Westerners.[105] Le Duan omitted to say that he was planning not only to remove the comprador bourgeoisie and the feudal landlord classes from the South, but also the national bourgeoisie as a whole.[106]

References

- ^ Le, Quynh (14 July 2006). "Vietnam ambivalent on Le Duan's legacy". BBC World News. BBC Online. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ a b c Shane-Armstrong 2003, p. 216.

- ^ Lien-Hang 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Woods 2002, p. 212.

- ^ Sawinski 2001, p. 211.

- ^ Tucker 2011, p. 637.

- ^ Currey 2005, p. 229.

- ^ Quinn-Judge 2002, p. 316.

- ^ a b c Ooi 2004, p. 777.

- ^ a b Ang 2002, p. 19.

- ^ Ang 2002, p. 24.

- ^ a b Ang 1997, p. 75.

- ^ Brocheux 2007, p. 167.

- ^ Lomperis 1996, p. 333. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLomperis1996 (help)

- ^ Ang 2002, p. 21.

- ^ a b Khoo 2011, p. 119.

- ^ Brocheux 2007, p. 174.

- ^ Brocheux 2007, p. 170.

- ^ a b Ang 2002, p. 10.

- ^ a b Roberts 2006, p. 482.

- ^ Woods 2002, p. 74.

- ^ Thai 1985, p. 54.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, p. 69.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, p. 70.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, p. 72.

- ^ Rothrock 2006, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Rothrock 2006, p. 56.

- ^ Rothrock 2006, p. 70.

- ^ Jones 2003, p. 213.

- ^ Jones 2003, p. 240.

- ^ a b c Dulker 1994, p. 357.

- ^ Roberts 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Rothrock 2006, p. 354.

- ^ Christie 1998, p. 291.

- ^ Desbarats, Jacqueline. "Repression in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam: Executions and Population Relocation", from The Vietnam Debate (1990) by John Morton Moore. "We know now from a 1985 statement by Nguyen Co Tach that two and a half million, rather than one million, people went through reeducation....in fact, possibly more than 100,000 Vietnamese people were victims of extrajudicial executions in the last ten years....it is likely that, overall, at least one million Vietnamese were the victims of forced population transfers."

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 1.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 2.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 3.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 5.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 78.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 79.

- ^ a b Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 80.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 81.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 87.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 88.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, p. 62.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 82.

- ^ Võ 1990, p. 81.

- ^ St. John 2006, p. 45.

- ^ St. John 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Võ 1990, p. 107.

- ^ a b Van & Cooper 1983, p. 227.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, pp. 227–228.

- ^ a b Van & Cooper 1983, p. 228.

- ^ a b Europa Publications 2002, pp. 1419–1420.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, p. 229.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, p. 230.

- ^ Zemtsov & Farrar 2007, p. 277.

- ^ Zemtsov & Farrar 2007, p. 285.

- ^ Zemtsov & Farrar 2007, p. 291.

- ^ Khoo 2011, p. 34.

- ^ Khoo 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Khoo 2011, p. 69.

- ^ Khoo 2011, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Khoo 2011, p. 97.

- ^ a b Khoo 2011, p. 98.

- ^ Khoo 2011, p. 117.

- ^ Khoo 2011, p. 118.

- ^ Khoo 2011, p. 100.

- ^ Khoo 2011, p. 123.

- ^ Võ 1990, p. 98.

- ^ "Vietnam - China". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Chinese invasion of Vietnam". Global Security.org. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d Quinn-Judge 2006, p. 166.

- ^ a b c Morris 1999, p. 96.

- ^ Morris 1999, p. 97.

- ^ Morris 1999, p. 93.

- ^ Morris 1999, p. 94.

- ^ Morris 1999, p. 95.

- ^ a b Morris 1999, p. 98.

- ^ Morris 1999, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Morris 1999, p. 100.

- ^ a b Morris 1999, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d Morris 1999, p. 102.

- ^ Morris 1999, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Morris 1999, p. 103.

- ^ Morris 1999, pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b Morris 1998, p. 108.

- ^ Morris 1999, p. 108.

- ^ a b Morris 1999, p. 109.

- ^ Morris 1999, p. 110.

- ^ Morris 1999, p. 111.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, p. 64.

- ^ a b Corfield 2008, pp. 111–112.

- ^ a b c d Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 140.

- ^ Võ 1990, p. 63.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, pp. 141–142.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Ronald J. Cima (December 1987). Ronald J. Cima (ed.). Vietnam: A Country Study. Federal Research Division. Constitutional Evolution.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Ronald J. Cima (December 1987). Ronald J. Cima (ed.). Vietnam: A Country Study. Federal Research Division. Constitutional Evolution.

- ^ a b c Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 141.

- ^ Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 137.

- ^ a b c Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council 1988, p. 138.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, p. 25.

- ^ Van & Cooper 1983, p. 26.

Bibliography

- Ang, Cheng Guan (1997). Vietnamese Communists' Relations with China and the Second Indochina Conflict, 1956–1962. McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786404049.

- Ang, Cheng Guan (2002). The Vietnam War From the Other Side: The Vietnamese Communists' Perspective. Routledge. ISBN 9780700716159.

- Brocheux, Pierre (2007). Ho Chi Minh: a Biography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521850629.

- Chen, King (1987). China's War With Vietnam, 1979: Issues, Decisions, and Implications. Hoover Press. ISBN 9780817985721.

- Christie, Clive J. (1998). Southeast Asia in the Twentieth Century: a Reader. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781860640636.

- Corfield, Justin (2008). The History of Vietnam. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313341946.

- Currey, Cecil B. (2005). Victory At Any Cost: The Genius of Viet Nam's Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 9781612340104.

- Duiker, William J. (1994). U.S. Containment Policy and the Conflict in Indochina. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804722834.

- Europa Publications (2002). Far East and Australasia. Routledge. ISBN 9781857431339.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Joint Committee on Southeast Asia of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council (1988). Postwar Vietnam: Dilemmas in Socialist Development. Southeast Asia Program Publications. ISBN 9780877271208.

- Jones, Howard (2003). Death of a Generation: How the Assassinations of Diem and JFK prolonged the Vietnam War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195052862.

- Khoo, Nicholas (2011). Collateral Damage: Sino–Soviet Rivalry and the Termination of the Sino–Vietnamese Alliance. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231150781.

- Lien-Hang, Nguyen (2012). Hanoi's War. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807882696.

- Lomperis, Timothy J. (1996). From People's War to People's Rule: Insurgency, Intervention, and the Lessons of Vietnam. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807845776.

- Morris, Stephen J. (1999). Why Vietnam invaded Cambodia: Political Culture and Causes of War. Chicago: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3049-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: a Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. Vol. 2. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576077702.

- Quinn-Judge, Sophie (2002). Ho Chi Minh: The Missing Years, 1919–1941. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520235335.

- Kiernan, Ben (2006). "External and Indigenous Sources of Khmer Rouge Ideology". In Westad, Odd A.; Sophie (eds.). The Third Indochina War: Conflict between China, Vietnam and Cambodia, 1972–79. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-39058-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2006). Behind the Bamboo Curtain: China, Vietnam, and the World Beyond Asia. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804755023.

- Rothrock, James (2006). Divided We Fall: How Disunity Leads to Defeat. AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781425911072.

- Sawinski, Diane M. (2001). Vietnam War: Biographies. U.X.L. ISBN 9780787648862.

- Shane-Armstrong, R. (2003). The Vietnam War. University of Wisconsin. ISBN 9780737714333.

- St. John, Ronald Bruce (2006). Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia: Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415701846.

- Thai, Quang Trung (2002). Collective Leadership and Factionalism: an Essay on Ho Chi Minh's Legacy. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789971988012.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099610.

- Van, Canh Nguyen; Cooper, Earle (1983). Vietnam under Communism, 1975–1982. Hoover Press. ISBN 9780817978518.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Võ, Nhân Trí (1990). Vietnam's Economic Policy since 1975. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789813035546.

- Woods, L. Shelton (2002). Vietnam: a Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576074169.

- Zemtsov, Ilya; Farrar, John (2007). Gorbachev: The Man and the System. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412807173.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)