String theory

| String theory |

|---|

|

| Fundamental objects |

| Perturbative theory |

| Non-perturbative results |

| Phenomenology |

| Mathematics |

| Beyond the Standard Model |

|---|

|

| Standard Model |

String theory is a physical theory that extends particle physics by replacing point particles by extended objects called strings. In string theory, the different types of observed elementary particles arise from the different quantum states of these strings. In addition to the types of particles postulated by the standard model of particle physics, string theory naturally incorporates gravity, and is therefore a candidate for a theory of everything, a self-contained mathematical model that describes all fundamental forces and forms of matter. Aside from this hypothesized role in particle physics, string theory is now widely used as a theoretical tool in physics, and it has shed light on many aspects of quantum field theory and quantum gravity.[1]

The earliest version of string theory, called bosonic string theory, incorporated only the class of particles known as bosons, although this theory developed into superstring theory, which posits that a connection (a "supersymmetry") exists between bosons and the class of particles called fermions. String theory requires the existence of extra spatial dimensions for its mathematical consistency. In realistic physical models constructed from string theory, these extra dimensions are typically compactified to extremely small scales.

String theory was first studied in the late 1960s as a theory of the strong nuclear force before being abandoned in favor of the theory of quantum chromodynamics. Subsequently, it was realized that the very properties that made string theory unsuitable as a theory of nuclear physics made it an outstanding candidate for a quantum theory of gravity. Five consistent versions of string theory were developed before it was realized in the mid-1990s that these theories could be obtained as different limits of a conjectured eleven-dimensional theory called M-theory.[2]

Many theoretical physicists (among them Stephen Hawking, Edward Witten, and Juan Maldacena) believe that string theory is a step towards the correct fundamental description of nature. This is because string theory allows for the consistent combination of quantum field theory and general relativity, agrees with general insights in quantum gravity such as the holographic principle and black hole thermodynamics, and because it has passed many non-trivial checks of its internal consistency. According to Hawking in particular, "M-theory is the only candidate for a complete theory of the universe."[3] Other physicists, such as Richard Feynman, Roger Penrose and Sheldon Lee Glashow, have criticized string theory for not providing novel experimental predictions at accessible energy scales.[4]

Overview

String theory posits that the electrons and quarks within an atom are not 0-dimensional objects, but made up of 1-dimensional strings. These strings can oscillate, giving the observed particles their flavor, charge, mass, and spin. Among the modes of oscillation of the string is a massless, spin-two state—a graviton. The existence of this graviton state and the fact that the equations describing string theory include Einstein's equations for general relativity mean that string theory is a quantum theory of gravity. Since string theory is widely believed[5] to be mathematically consistent, many hope that it fully describes our universe, making it a theory of everything. String theory is known to contain configurations that describe all the observed fundamental forces and matter but with a zero cosmological constant and some new fields.[6] Other configurations have different values of the cosmological constant, and are metastable but long-lived. This leads many to believe that there is at least one metastable solution that is quantitatively identical with the standard model, with a small cosmological constant, containing dark matter and a plausible mechanism for cosmic inflation. It is not yet known whether string theory has such a solution, nor how much freedom the theory allows to choose the details.

String theories also include objects other than strings, called branes. The word brane, derived from "membrane", refers to a variety of interrelated objects, such as D-branes, black p-branes, and Neveu–Schwarz 5-branes. These are extended objects that are charged sources for differential form generalizations of the vector potential electromagnetic field. These objects are related to one another by a variety of dualities. Black hole-like black p-branes are identified with D-branes, which are endpoints for strings, and this identification is called Gauge-gravity duality. Research on this equivalence has led to new insights on quantum chromodynamics, the fundamental theory of the strong nuclear force.[7][8][9][10] The strings make closed loops unless they encounter D-branes, where they can open up into 1-dimensional lines. The endpoints of the string cannot break off the D-brane, but they can slide around on it.

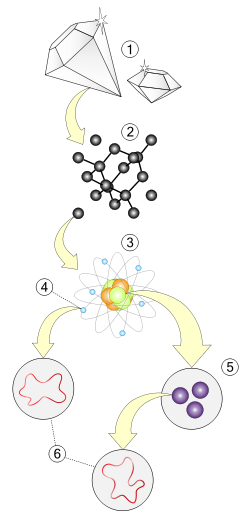

1. Macroscopic level – Matter

2. Molecular level

3. Atomic level – Protons, neutrons, and electrons

4. Subatomic level – Electron

5. Subatomic level – Quarks

6. String level

The full theory does not yet have a satisfactory definition in all circumstances, since the scattering of strings is most straightforwardly defined by a perturbation theory. The complete quantum mechanics of high dimensional branes is not easily defined, and the behavior of string theory in cosmological settings (time-dependent backgrounds) is not fully worked out. It is also not clear as to whether there is any principle by which string theory selects its vacuum state, the spacetime configuration that determines the properties of our universe (see string theory landscape).

| Type | Spacetime dimensions (1T Physics) | Space + Time dimensions (2T Physics) | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Spacetime | 3+1 | 4+2 | Only bosons, no fermions, meaning only forces, no matter, with both open and closed strings; major flaw: a particle with imaginary mass, called the tachyon, representing an instability in the theory. |

| Bosonic | 25+1 | 26+2 | Only bosons, no fermions, meaning only forces, no matter, with both open and closed strings; major flaw: a particle with imaginary mass, called the tachyon, representing an instability in the theory. |

| I | 9+1 | 10 + 2 | Supersymmetry between forces and matter, with both open and closed strings; no tachyon; group symmetry is SO(32) |

| IIA | 9+1 | 10+2 | Supersymmetry between forces and matter, with only closed strings bound to D-branes; no tachyon; massless fermions are non-chiral |

| IIB | 9+1 | 10+2 | Supersymmetry between forces and matter, with only closed strings bound to D-branes; no tachyon; massless fermions are chiral |

| HO | 9+1 | 10+2 | Supersymmetry between forces and matter, with closed strings only; no tachyon; heterotic, meaning right moving and left moving strings differ; group symmetry is SO(32) |

| HE | 9+1 | 10+2 | Supersymmetry between forces and matter, with closed strings only; no tachyon; heterotic; group symmetry is E8×E8 |

| M-Theory | 10+1 | 12+2 | Not a finished theory yet, it is hoped that this may unify all other String theories. ]] |

Note that in the type IIA and type IIB string theories closed strings are allowed to move everywhere throughout the ten-dimensional spacetime (called the bulk), while open strings have their ends attached to D-branes, which are membranes of lower dimensionality (their dimension is odd — 1, 3, 5, 7 or 9 — in type IIA and even — 0, 2, 4, 6 or 8 — in type IIB, including the time direction).

Basic properties

String theory can be formulated in terms of an action principle, either the Nambu-Goto action or the Polyakov action, which describe how strings propagate through space and time. In the absence of external interactions, string dynamics are governed by tension and kinetic energy, which combine to produce oscillations. The quantum mechanics of strings implies these oscillations exist in discrete vibrational modes, the spectrum of the theory.

On distance scales larger than the string radius, each oscillation mode behaves as a different species of particle, with its mass, spin and charge determined by the string's dynamics. Splitting and recombination of strings correspond to particle emission and absorption, giving rise to the interactions between particles. An analogy for strings' modes of vibration is a guitar string's production of multiple distinct musical notes. In the analogy, different notes correspond to different particles. One difference is the guitar string exists in 3 dimensions, so that there are only two dimensions transverse to the string. Fundamental strings exist in 10 dimensions and the strings can vibrate in any direction, meaning that the spectrum of vibrational modes is much richer.

String theory includes both open strings, which have two distinct endpoints, and closed strings making a complete loop. The two types of string behave in slightly different ways, yielding two different spectra. For example, all string theories have closed string graviton modes, but only open strings can vibrate as photons. Because the two ends of an open string can always meet and connect, forming a closed string, there are no string theories without closed strings.

The earliest string model, the bosonic string, incorporated only bosonic degrees of freedom. This model describes, in low enough energies, a quantum gravity theory, which also includes (if open strings are incorporated as well) gauge fields such as the photon (or, in more general terms, any gauge theory). However, this model has problems. What is most significant is that the theory has a fundamental instability, believed to result in the decay (at least partially) of spacetime itself. In addition, as the name implies, the spectrum of particles contains only bosons, particles which, like the photon, obey particular rules of behavior. In broad terms, bosons are the constituents of radiation, but not of matter, which is made of fermions. Investigating how a string theory may include fermions in its spectrum led to the invention of supersymmetry, a mathematical relation between bosons and fermions. String theories that include fermionic vibrations are now known as superstring theories; several kinds have been described, but all are now thought to be different limits of M-theory.

Some qualitative properties of quantum strings can be understood in a fairly simple fashion. For example, quantum strings have tension, much like regular strings made of twine; this tension is considered a fundamental parameter of the theory. The tension of a quantum string is closely related to its size. Consider a closed loop of string, left to move through space without external forces. Its tension will tend to contract it into a smaller and smaller loop. Classical intuition suggests that it might shrink to a single point, but this would violate Heisenberg's uncertainty principle. The characteristic size of the string loop will be a balance between the tension force, acting to make it small, and the uncertainty effect, which keeps it "stretched". As a consequence, the minimum size of a string is related to the string tension.

Worldsheet

A point-like particle's motion may be described by drawing a graph of its position (in one or two dimensions of space) against time. The resulting picture depicts the worldline of the particle (its 'history') in spacetime. By analogy, a similar graph depicting the progress of a string as time passes by can be obtained; the string (a one-dimensional object — a small line — by itself) will trace out a surface (a two-dimensional manifold), known as the worldsheet. The different string modes (representing different particles, such as photon or graviton) are surface waves on this manifold.

A closed string looks like a small loop, so its worldsheet will look like a pipe or, in more general terms, a Riemann surface (a two-dimensional oriented manifold) with no boundaries (i.e., no edge). An open string looks like a short line, so its worldsheet will look like a strip or, in more general terms, a Riemann surface with a boundary.

Strings can split and connect. This is reflected by the form of their worldsheet (in more accurate terms, by its topology). For example, if a closed string splits, its worldsheet will look like a single pipe splitting (or connected) to two pipes (often referred to as a pair of pants — see drawing at right). If a closed string splits and its two parts later reconnect, its worldsheet will look like a single pipe splitting to two and then reconnecting, which also looks like a torus connected to two pipes (one representing the ingoing string, and the other — the outgoing one). An open string doing the same thing will have its worldsheet looking like a ring connected to two strips.

Note that the process of a string splitting (or strings connecting) is a global process of the worldsheet, not a local one: Locally, the worldsheet looks the same everywhere, and it is not possible to determine a single point on the worldsheet where the splitting occurs. Therefore, these processes are an integral part of the theory, and are described by the same dynamics that controls the string modes.

In some string theories (namely, closed strings in Type I and some versions of the bosonic string), strings can split and reconnect in an opposite orientation (as in a Möbius strip or a Klein bottle). These theories are called unoriented. In formal terms, the worldsheet in these theories is a non-orientable surface.

Dualities

Before the 1990s, string theorists believed there were five distinct superstring theories: open type I, closed type I, closed type IIA, closed type IIB, and the two flavors of heterotic string theory (SO(32) and E8×E8).[11] The thinking was that out of these five candidate theories, only one was the actual correct theory of everything, and that theory was the one whose low energy limit, with ten spacetime dimensions compactified down to four, matched the physics observed in our world today. It is now believed that this picture was incorrect and that the five superstring theories are connected to one another as if they are each a special case of some more fundamental theory (thought to be M-theory). These theories are related by transformations that are called dualities. If two theories are related by a duality transformation, it means that the first theory can be transformed in some way so that it ends up looking just like the second theory. The two theories are then said to be dual to one another under that kind of transformation. Put differently, the two theories are mathematically different descriptions of the same phenomena.

These dualities link quantities that were also thought to be separate. Large and small distance scales, as well as strong and weak coupling strengths, are quantities that have always marked very distinct limits of behavior of a physical system in both classical field theory and quantum particle physics. But strings can obscure the difference between large and small, strong and weak, and this is how these five very different theories end up being related. T-duality relates the large and small distance scales between string theories, whereas S-duality relates strong and weak coupling strengths between string theories. U-duality links T-duality and S-duality.

Dimensions

Number of dimensions

An intriguing feature of string theory is that it predicts extra dimensions. In classical string theory the number of dimensions is not fixed by any consistency criterion. However, to make a consistent quantum theory, string theory is required to live in a spacetime of the so-called "critical dimension": we must have 26 spacetime dimensions for the bosonic string and 10 for the superstring. This is necessary to ensure the vanishing of the conformal anomaly of the worldsheet conformal field theory. Modern understanding indicates that there exist less-trivial ways of satisfying this criterion. Cosmological solutions exist in a wider variety of dimensionalities, and these different dimensions are related by dynamical transitions. The dimensions are more precisely different values of the "effective central charge", a count of degrees of freedom that reduces to dimensionality in weakly curved regimes.[12][13]

One such theory is the 11-dimensional M-theory, which requires spacetime to have eleven dimensions,[14] as opposed to the usual three spatial dimensions and the fourth dimension of time. The original string theories from the 1980s describe special cases of M-theory where the eleventh dimension is a very small circle or a line, and if these formulations are considered as fundamental, then string theory requires ten dimensions. But the theory also describes universes like ours, with four observable spacetime dimensions, as well as universes with up to 10 flat space dimensions, and also cases where the position in some of the dimensions is described by a complex number rather than a real number. The notion of spacetime dimension is not fixed in string theory: it is best thought of as different in different circumstances.[15]

Nothing in Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism or Einstein's theory of relativity makes this kind of prediction; these theories require physicists to insert the number of dimensions manually and arbitrarily, and this number is fixed and independent of potential energy. String theory allows one to relate the number of dimensions to scalar potential energy. In technical terms, this happens because a gauge anomaly exists for every separate number of predicted dimensions, and the gauge anomaly can be counteracted by including nontrivial potential energy into equations to solve motion. Furthermore, the absence of potential energy in the "critical dimension" explains why flat spacetime solutions are possible.

This can be better understood by noting that a photon included in a consistent theory (technically, a particle carrying a force related to an unbroken gauge symmetry) must be massless. The mass of the photon that is predicted by string theory depends on the energy of the string mode that represents the photon. This energy includes a contribution from the Casimir effect, namely from quantum fluctuations in the string. The size of this contribution depends on the number of dimensions, since for a larger number of dimensions there are more possible fluctuations in the string position. Therefore, the photon in flat spacetime will be massless—and the theory consistent—only for a particular number of dimensions.[16] When the calculation is done, the critical dimensionality is not four as one may expect (three axes of space and one of time). The subset of X is equal to the relation of photon fluctuations in a linear dimension. Flat space string theories are 26-dimensional in the bosonic case, while superstring and M-theories turn out to involve 10 or 11 dimensions for flat solutions. In bosonic string theories, the 26 dimensions come from the Polyakov equation.[17] Starting from any dimension greater than four, it is necessary to consider how these are reduced to four dimensional spacetime.

Multiple Time Dimensions

Special Relativity Allows for Multiple_time_dimensions beyond the 1 dimensional time we currently perceive. Recently there has been some debate as to whether two dimensional time might be required to better explain the physics of the universe, a suggestion put forth by PhysicistItzhak Bars called "Two Time Physics" (or "2T Physics")[18]. This theory is that we have an extra dimension of time (and therefore, also an extra dimension of space) present, so instead of 4 (3 space + 1 time) dimensions as classical space describes we have 6 (4 space + 1 time).

If this is true, it would also require adding an additional time dimension (and therefore spacial dimension as well) to all string theories currently being studied. One reason this theory is attractive is that it provides symmetry to all the equations, which is otherwise lacking.[19] According to his work, while adding more than 2 dimensions of time can require things such as "Negative Imaginary Time", adding only a second dimension allows the dimensions to fold back over themselves and cancel out any contradictory values.

Although two dimensional time may allow for time-travel paradoxes to become possible, Berndt Müller of Columbia University, recently gave a presentation at Duke University, on how two dimensional time may be affected by thermal energy, which he showed may negate concerns of paradoxes from occurring.[20] when they are compressed.If true this would allow for a symmetrical universe which can explain symetriry loss at very close values, ab so long as there arre only two dimensions of time then there are no conflicts in terms of our observed universe and one with two dimension the do not live in a 4 dimensional world, but, actually a 6 dimensional world According this which he claims can be applied to the classical 3+1 "4 Dimensional spacetime"

Compact dimensions

Two ways have been proposed to resolve this apparent contradiction. The first is to compactify the extra dimensions; i.e., the 6 or 7 extra dimensions are so small as to be undetectable by present-day experiments.

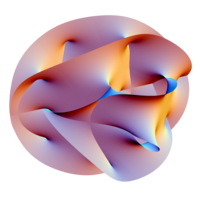

To retain a high degree of supersymmetry, these compactification spaces must be very special, as reflected in their holonomy. A 6-dimensional manifold must have SU(3) structure, a particular case (torsionless) of this being SU(3) holonomy, making it a Calabi–Yau space, and a 7-dimensional manifold must have G2 structure, with G2 holonomy again being a specific, simple, case. Such spaces have been studied in attempts to relate string theory to the 4-dimensional Standard Model, in part due to the computational simplicity afforded by the assumption of supersymmetry. More recently, progress has been made constructing more realistic compactifications without the degree of symmetry of Calabi–Yau or G2 manifolds.[citation needed]

A standard analogy for this is to consider multidimensional space as a garden hose. If the hose is viewed from a sufficient distance, it appears to have only one dimension, its length. Indeed, think of a ball just small enough to enter the hose. Throwing such a ball inside the hose, the ball would move more or less in one dimension; in any experiment we make by throwing such balls in the hose, the only important movement will be one-dimensional, that is, along the hose. However, as one approaches the hose, one discovers that it contains a second dimension, its circumference. Thus, an ant crawling inside it would move in two dimensions (and a fly flying in it would move in three dimensions). This "extra dimension" is only visible within a relatively close range to the hose, or if one "throws in" small enough objects. Similarly, the extra compact dimensions are only "visible" at extremely small distances, or by experimenting with particles with extremely small wavelengths (of the order of the compact dimension's radius), which in quantum mechanics means very high energies (see wave-particle duality).

Brane-world scenario

Another possibility is that we are "stuck" in a 3+1 dimensional (three spatial dimensions plus one time dimension) subspace of the full universe. Properly localized matter and Yang-Mills gauge fields will typically exist if the sub-spacetime is an exceptional set of the larger universe.[21] These "exceptional sets" are ubiquitous in Calabi–Yau n-folds and may be described as subspaces without local deformations, akin to a crease in a sheet of paper or a crack in a crystal, the neighborhood of which is markedly different from the exceptional subspace itself. However, until the work of Randall and Sundrum,[22] it was not known that gravity can be properly localized to a sub-spacetime. In addition, spacetime may be stratified, containing strata of various dimensions, allowing us to inhabit the 3+1-dimensional stratum—such geometries occur naturally in Calabi–Yau compactifications.[23] Such sub-spacetimes are D-branes, hence such models are known as brane-world scenarios.

Effect of the hidden dimensions

In either case, gravity acting in the hidden dimensions affects other non-gravitational forces such as electromagnetism. In fact, Kaluza's early work demonstrated that general relativity in five dimensions actually predicts the existence of electromagnetism. However, because of the nature of Calabi–Yau manifolds, no new forces appear from the small dimensions, but their shape has a profound effect on how the forces between the strings appear in our four-dimensional universe. In principle, therefore, it is possible to deduce the nature of those extra dimensions by requiring consistency with the standard model, but this is not yet a practical possibility. It is also possible to extract information regarding the hidden dimensions by precision tests of gravity, but so far these have only put upper limitations on the size of such hidden dimensions.

D-branes

Another key feature of string theory is the existence of D-branes. These are membranes of different dimensionality (anywhere from a zero dimensional membrane—which is in fact a point—and up, including 2-dimensional membranes, 3-dimensional volumes, and so on).

D-branes are defined by the fact that worldsheet boundaries are attached to them. D-branes have mass, since they emit and absorb closed strings that describe gravitons, and — in superstring theories — charge as well, since they couple to open strings that describe gauge interactions.

From the point of view of open strings, D-branes are objects to which the ends of open strings are attached. The open strings attached to a D-brane are said to "live" on it, and they give rise to gauge theories "living" on it (since one of the open string modes is a gauge boson such as the photon). In the case of one D-brane there will be one type of a gauge boson and we will have an Abelian gauge theory (with the gauge boson being the photon). If there are multiple parallel D-branes there will be multiple types of gauge bosons, giving rise to a non-Abelian gauge theory.

D-branes are thus gravitational sources, on which a gauge theory "lives". This gauge theory is coupled to gravity (which is said to exist in the bulk), so that normally each of these two viewpoints is incomplete.

Testability and experimental predictions

Several major difficulties complicate efforts to test string theory. The most significant is the extremely small size of the Planck length, which is expected to be close to the string length (the characteristic size of a string, where strings become easily distinguishable from particles). Another issue is the huge number of metastable vacua of string theory, which might be sufficiently diverse to accommodate almost any phenomena we might observe at lower energies.

Predictions

String harmonics

One unique prediction of string theory is the existence of string harmonics: at sufficiently high energies, the string-like nature of particles would become obvious. There should be heavier copies of all particles, corresponding to higher vibrational harmonics of the string. It is not clear how high these energies are. In most conventional string models they would be not far below the Planck energy, around 1014 times higher than the energies accessible in the newest particle accelerator, the LHC, making this prediction impossible to test with any particle accelerator in the near future. However, in models with large extra dimensions they could potentially be produced at the LHC or at energies not far above its reach.

Cosmology

String theory as currently understood makes a series of predictions for the structure of the universe at the largest scales. Many phases in string theory have very large, positive vacuum energy.[24] Regions of the universe that are in such a phase will inflate exponentially rapidly in a process known as eternal inflation. As such, the theory predicts that most of the universe is very rapidly expanding. However, these expanding phases are not stable, and can decay via the nucleation of bubbles of lower vacuum energy. Since our local region of the universe is not very rapidly expanding, string theory predicts we are inside such a bubble. The spatial curvature of the "universe" inside the bubbles that form by this process is negative, a testable prediction.[25] Moreover, other bubbles will eventually form in the parent vacuum outside the bubble and collide with it. These collisions lead to potentially observable imprints on cosmology.[26][27] However, it is possible that neither of these will be observed if the spatial curvature is too small and the collisions are too rare.

Cosmic strings

Under certain circumstances, fundamental strings produced at or near the end of inflation can be "stretched" to astronomical proportions. These cosmic strings could be observed in various ways, for instance by their gravitational lensing effects. However, certain field theories also predict cosmic strings arising from topological defects in the field configuration.[28]

Strength of gravity

Theories with extra dimensions predict that the strength of gravity increases much more rapidly at small distances than is the case in 3 dimensions (where it increase as r−2). Depending on the size of the dimensions, this could lead to phenomena such as the production of micro black holes at the LHC, or be detected in microgravity experiments.

Supersymmetry

If confirmed experimentally, supersymmetry could also be considered evidence, because it was discovered in the context of string theory, and all consistent string theories are supersymmetric. However, the absence of supersymmetric particles at energies accessible to the LHC would not necessarily disprove string theory, since the energy scale at which supersymmetry is broken could be well above the accelerator's range.

A central problem for applications is that the best-understood backgrounds of string theory preserve much of the supersymmetry of the underlying theory, which results in time-invariant spacetimes: At present, string theory cannot deal well with time-dependent, cosmological backgrounds. However, several models have been proposed to predict supersymmetry breaking, the most notable one being the KKLT model,[24] which incorporates branes and fluxes to make a metastable compactification.

Coupling constant unification

Grand unification natural in string theories of everything requires that the coupling constants of the four forces meet at one point under renormalization group rescaling. This is also a falsifiable statement, but it is not restricted to string theory, but is shared by grand unified theories.[29] The LHC will be used both for testing AdS/CFT, and to check if the electroweakstrong unification does happen as predicted.[30]

AdS/CFT correspondence

The anti-de Sitter/conformal field theory (AdS/CFT) correspondence is a relationship which says that string theory is in certain cases equivalent to a quantum field theory. More precisely, one considers string or M-theory on an anti-de Sitter background. This means that the geometry of spacetime is obtained by perturbing a certain solution of Einstein's equation in the vacuum. In this setting, it is possible to define a notion of "boundary" of spacetime. The AdS/CFT correspondence states that this boundary can be regarded as the "spacetime" for a quantum field theory, and this field theory is equivalent to the bulk gravitational theory in the sense that there is a "dictionary" for translating calculations in one theory into calculations in the other.

Examples of the correspondence

The most famous example of the AdS/CFT correspondence states that Type IIB string theory on the product AdS5 × S5 is equivalent to N = 4 supersymmetric Yang–Mills theory on the four-dimensional conformal boundary.[31][32][33][34] Two more important examples are M-theory on AdS4 × S7, described by the ABJM superconformal field theory in 2+1 dimensions,[35] and M-theory on AdS7 × S4, described by the so-called (2,0)-theory in 5+1 dimensions.[36] The latter theory is predicted to exist by the classification of superconformal field theories,[37] but it admits no known Lagrangian description. The same used to be true of the ABJM theory before its Lagrangian description was found.[38]

Applications to quantum chromodynamics

String theory was originally proposed as a theory of hadrons, and its study has led to new insights on quantum chromodynamics, the fundamental theory of the strong nuclear force. For example, the the AdS/CFT correspondence relates string theory to supersymmetric Yang–Mills theory, which provides a good approximation to quantum chromodynamics. The correspondence has been used to describe qualitative features of an exotic state of matter called the quark–gluon plasma by translating problems involving the quark-gluon plasma into problems involving gravity and black holes.[7][8][9][10] The physics, however, is strictly that of standard quantum chromodynamics, which has been quantitatively modeled by lattice QCD methods with good results.[39] Many physicists hope that work in string theory will lead to the discovery of a gravitational theory which is equivalent (under the AdS/CFT correspondence) to quantum chromodynamics.[40] Such a theory would allow physicists to do calculations which are impossible in the usual formalism of quantum field theory. This type of string theory, which describes only nuclear physics, is much less controversial today than string theories of everything, although two decades ago it was the other way around.[41]

Connections to mathematics

In addition to influencing research in theoretical physics, string theory has stimulated a number of major developments in pure mathematics. Like many developing ideas in theoretical physics, string theory does not at present have a mathematically rigorous formulation in which all of its concepts can be defined precisely. As a result, physicists who study string theory are often guided by physical intuition to conjecture relationships between the seemingly different mathematical structures that are used to formalize different parts of the theory. These conjectures are later proved by mathematicians, and in this way, string theory has served as a source of new ideas in pure mathematics.[42]

Mirror symmetry

One of the ways in which string theory influenced mathematics was through the discovery of mirror symmetry. In string theory, the shape of the unobserved spatial dimensions is typically encoded in mathematical objects called Calabi-Yau manifolds. These are of interest in pure mathematics, and they can be used to construct realistic models of physics from string theory. In the late 1980s, it was noticed that given a such a physical model, it is not possible to uniquely reconstruct a corresponding Calabi-Yau manifold. Instead, one finds that there are two Calabi-Yau manifolds that give rise to the same physics. These manifolds are said to be "mirror" to one another. The existence of this mirror symmetry relationship between different Calabi-Yau manifolds has significant mathematical consequences as it allows mathematicians to solve many problems in enumerative algebraic geometry. Today mathematicians are still working to develop a mathematical understanding of mirror symmetry based on physicists' intuition.[43]

Vertex operator algebras

In addition to mirror symmetry, applications of string theory to pure mathematics include results in the theory of vertex operator algebras. For example, ideas from string theory were used by Richard Borcherds in 1992 to prove the monstrous moonshine conjecture relating the monster group (a construction arising in group theory, a branch of algebra) and modular functions (a class of functions which are important in number theory).[44]

History

Some of the structures reintroduced by string theory arose for the first time much earlier as part of the program of classical unification started by Albert Einstein. The first person to add a fifth dimension to general relativity was German mathematician Theodor Kaluza in 1919, who noted that gravity in five dimensions describes both gravity and electromagnetism in four. In 1926, the Swedish physicist Oskar Klein gave a physical interpretation of the unobservable extra dimension — it is wrapped into a small circle. Einstein introduced a non-symmetric metric tensor, while much later Brans and Dicke added a scalar component to gravity. These ideas would be revived within string theory, where they are demanded by consistency conditions.

String theory was originally developed during the late 1960s and early 1970s as a never completely successful theory of hadrons, the subatomic particles like the proton and neutron that feel the strong interaction. In the 1960s, Geoffrey Chew and Steven Frautschi discovered that the mesons make families called Regge trajectories with masses related to spins in a way that was later understood by Yoichiro Nambu, Holger Bech Nielsen and Leonard Susskind to be the relationship expected from rotating strings. Chew advocated making a theory for the interactions of these trajectories that did not presume that they were composed of any fundamental particles, but would construct their interactions from self-consistency conditions on the S-matrix. The S-matrix approach was started by Werner Heisenberg in the 1940s as a way of constructing a theory that did not rely on the local notions of space and time, which Heisenberg believed break down at the nuclear scale. While the scale was off by many orders of magnitude, the approach he advocated was ideally suited for a theory of quantum gravity.

Working with experimental data, R. Dolen, D. Horn and C. Schmid[45] developed some sum rules for hadron exchange. When a particle and antiparticle scatter, virtual particles can be exchanged in two qualitatively different ways. In the s-channel, the two particles annihilate to make temporary intermediate states that fall apart into the final state particles. In the t-channel, the particles exchange intermediate states by emission and absorption. In field theory, the two contributions add together, one giving a continuous background contribution, the other giving peaks at certain energies. In the data, it was clear that the peaks were stealing from the background — the authors interpreted this as saying that the t-channel contribution was dual to the s-channel one, meaning both described the whole amplitude and included the other.

The result was widely advertised by Murray Gell-Mann, leading Gabriele Veneziano to construct a scattering amplitude that had the property of Dolen-Horn-Schmid duality, later renamed world-sheet duality. The amplitude needed poles where the particles appear, on straight line trajectories, and there is a special mathematical function whose poles are evenly spaced on half the real line— the Gamma function— which was widely used in Regge theory. By manipulating combinations of Gamma functions, Veneziano was able to find a consistent scattering amplitude with poles on straight lines, with mostly positive residues, which obeyed duality and had the appropriate Regge scaling at high energy. The amplitude could fit near-beam scattering data as well as other Regge type fits, and had a suggestive integral representation that could be used for generalization.

Over the next years, hundreds of physicists worked to complete the bootstrap program for this model, with many surprises. Veneziano himself discovered that for the scattering amplitude to describe the scattering of a particle that appears in the theory, an obvious self-consistency condition, the lightest particle must be a tachyon. Miguel Virasoro and Joel Shapiro found a different amplitude now understood to be that of closed strings, while Ziro Koba and Holger Nielsen generalized Veneziano's integral representation to multiparticle scattering. Veneziano and Sergio Fubini introduced an operator formalism for computing the scattering amplitudes that was a forerunner of world-sheet conformal theory, while Virasoro understood how to remove the poles with wrong-sign residues using a constraint on the states. Claud Lovelace calculated a loop amplitude, and noted that there is an inconsistency unless the dimension of the theory is 26. Charles Thorn, Peter Goddard and Richard Brower went on to prove that there are no wrong-sign propagating states in dimensions less than or equal to 26.

In 1969, Yoichiro Nambu, Holger Bech Nielsen, and Leonard Susskind recognized that the theory could be given a description in space and time in terms of strings. The scattering amplitudes were derived systematically from the action principle by Peter Goddard, Jeffrey Goldstone, Claudio Rebbi, and Charles Thorn, giving a space-time picture to the vertex operators introduced by Veneziano and Fubini and a geometrical interpretation to the Virasoro conditions.

In 1970, Pierre Ramond added fermions to the model, which led him to formulate a two-dimensional supersymmetry to cancel the wrong-sign states. John Schwarz and André Neveu added another sector to the fermi theory a short time later. In the fermion theories, the critical dimension was 10. Stanley Mandelstam formulated a world sheet conformal theory for both the bose and fermi case, giving a two-dimensional field theoretic path-integral to generate the operator formalism. Michio Kaku and Keiji Kikkawa gave a different formulation of the bosonic string, as a string field theory, with infinitely many particle types and with fields taking values not on points, but on loops and curves.

In 1974, Tamiaki Yoneya discovered that all the known string theories included a massless spin-two particle that obeyed the correct Ward identities to be a graviton. John Schwarz and Joel Scherk came to the same conclusion and made the bold leap to suggest that string theory was a theory of gravity, not a theory of hadrons. They reintroduced Kaluza–Klein theory as a way of making sense of the extra dimensions. At the same time, quantum chromodynamics was recognized as the correct theory of hadrons, shifting the attention of physicists and apparently leaving the bootstrap program in the dustbin of history.

String theory eventually made it out of the dustbin, but for the following decade all work on the theory was completely ignored. Still, the theory continued to develop at a steady pace thanks to the work of a handful of devotees. Ferdinando Gliozzi, Joel Scherk, and David Olive realized in 1976 that the original Ramond and Neveu Schwarz-strings were separately inconsistent and needed to be combined. The resulting theory did not have a tachyon, and was proven to have space-time supersymmetry by John Schwarz and Michael Green in 1981. The same year, Alexander Polyakov gave the theory a modern path integral formulation, and went on to develop conformal field theory extensively. In 1979, Daniel Friedan showed that the equations of motions of string theory, which are generalizations of the Einstein equations of General Relativity, emerge from the Renormalization group equations for the two-dimensional field theory. Schwarz and Green discovered T-duality, and constructed two superstring theories — IIA and IIB related by T-duality, and type I theories with open strings. The consistency conditions had been so strong, that the entire theory was nearly uniquely determined, with only a few discrete choices.

In the early 1980s, Edward Witten discovered that most theories of quantum gravity could not accommodate chiral fermions like the neutrino. This led him, in collaboration with Luis Alvarez-Gaumé to study violations of the conservation laws in gravity theories with anomalies, concluding that type I string theories were inconsistent. Green and Schwarz discovered a contribution to the anomaly that Witten and Alvarez-Gaumé had missed, which restricted the gauge group of the type I string theory to be SO(32). In coming to understand this calculation, Edward Witten became convinced that string theory was truly a consistent theory of gravity, and he became a high-profile advocate. Following Witten's lead, between 1984 and 1986, hundreds of physicists started to work in this field, and this is sometimes called the first superstring revolution.

During this period, David Gross, Jeffrey Harvey, Emil Martinec, and Ryan Rohm discovered heterotic strings. The gauge group of these closed strings was two copies of E8, and either copy could easily and naturally include the standard model. Philip Candelas, Gary Horowitz, Andrew Strominger and Edward Witten found that the Calabi-Yau manifolds are the compactifications that preserve a realistic amount of supersymmetry, while Lance Dixon and others worked out the physical properties of orbifolds, distinctive geometrical singularities allowed in string theory. Cumrun Vafa generalized T-duality from circles to arbitrary manifolds, creating the mathematical field of mirror symmetry. Daniel Friedan, Emil Martinec and Stephen Shenker further developed the covariant quantization of the superstring using conformal field theory techniques. David Gross and Vipul Periwal discovered that string perturbation theory was divergent. Stephen Shenker showed it diverged much faster than in field theory suggesting that new non-perturbative objects were missing.

In the 1990s, Joseph Polchinski discovered that the theory requires higher-dimensional objects, called D-branes and identified these with the black-hole solutions of supergravity. These were understood to be the new objects suggested by the perturbative divergences, and they opened up a new field with rich mathematical structure. It quickly became clear that D-branes and other p-branes, not just strings, formed the matter content of the string theories, and the physical interpretation of the strings and branes was revealed — they are a type of black hole. Leonard Susskind had incorporated the holographic principle of Gerardus 't Hooft into string theory, identifying the long highly excited string states with ordinary thermal black hole states. As suggested by 't Hooft, the fluctuations of the black hole horizon, the world-sheet or world-volume theory, describes not only the degrees of freedom of the black hole, but all nearby objects too.

In 1995, at the annual conference of string theorists at the University of Southern California (USC), Edward Witten gave a speech on string theory that in essence united the five string theories that existed at the time, and giving birth to a new 11-dimensional theory called M-theory. M-theory was also foreshadowed in the work of Paul Townsend at approximately the same time. The flurry of activity that began at this time is sometimes called the second superstring revolution.

During this period, Tom Banks, Willy Fischler, Stephen Shenker and Leonard Susskind formulated matrix theory, a full holographic description of M-theory using IIA D0 branes.[46] This was the first definition of string theory that was fully non-perturbative and a concrete mathematical realization of the holographic principle. It is an example of a gauge-gravity duality and is now understood to be a special case of the AdS/CFT correspondence. Andrew Strominger and Cumrun Vafa calculated the entropy of certain configurations of D-branes and found agreement with the semi-classical answer for extreme charged black holes. Petr Hořava and Edward Witten found the eleven-dimensional formulation of the heterotic string theories, showing that orbifolds solve the chirality problem. Witten noted that the effective description of the physics of D-branes at low energies is by a supersymmetric gauge theory, and found geometrical interpretations of mathematical structures in gauge theory that he and Nathan Seiberg had earlier discovered in terms of the location of the branes.

In 1997, Juan Maldacena noted that the low energy excitations of a theory near a black hole consist of objects close to the horizon, which for extreme charged black holes looks like an anti de Sitter space. He noted that in this limit the gauge theory describes the string excitations near the branes. So he hypothesized that string theory on a near-horizon extreme-charged black-hole geometry, an anti-deSitter space times a sphere with flux, is equally well described by the low-energy limiting gauge theory, the N=4 supersymmetric Yang-Mills theory. This hypothesis, which is called the AdS/CFT correspondence, was further developed by Steven Gubser, Igor Klebanov and Alexander Polyakov, and by Edward Witten, and it is now well-accepted. It is a concrete realization of the holographic principle, which has far-reaching implications for black holes, locality and information in physics, as well as the nature of the gravitational interaction. Through this relationship, string theory has been shown to be related to gauge theories like quantum chromodynamics and this has led to more quantitative understanding of the behavior of hadrons, bringing string theory back to its roots.

Criticisms

Some critics of string theory say that it is a failure as a theory of everything.[47][48][49][50][51][52] Notable critics include Peter Woit, Lee Smolin, Philip Warren Anderson,[53] Sheldon Glashow,[54] Lawrence Krauss,[55] and Carlo Rovelli.[56] Some common criticisms include:

- Very high energies needed to test quantum gravity.

- Lack of uniqueness of predictions due to the large number of solutions.

- Lack of background independence.

High energies

It is widely believed that any theory of quantum gravity would require extremely high energies to probe directly, higher by orders of magnitude than those that current experiments such as the Large Hadron Collider[57] can attain. This is because strings themselves are expected to be only slightly larger than the Planck length, which is twenty orders of magnitude smaller than the radius of a proton, and high energies are required to probe small length scales. Generally speaking, quantum gravity is difficult to test because the gravity is much weaker than the other forces, and because quantum effects are controlled by Planck's constant h, a very small quantity. As a result, the effects of quantum gravity are extremely weak.

Number of solutions

String theory as it is currently understood has a huge number of solutions, called string vacua,[24] and these vacua might be sufficiently diverse to accommodate almost any phenomena we might observe at lower energies.

The vacuum structure of the theory, called the string theory landscape (or the anthropic portion of string theory vacua), is not well understood. String theory contains an infinite number of distinct meta-stable vacua, and perhaps 10520 of these or more correspond to a universe roughly similar to ours — with four dimensions, a high planck scale, gauge groups, and chiral fermions. Each of these corresponds to a different possible universe, with a different collection of particles and forces.[24] What principle, if any, can be used to select among these vacua is an open issue. While there are no continuous parameters in the theory, there is a very large set of possible universes, which may be radically different from each other. It is also suggested that the landscape is surrounded by an even more vast swampland of consistent-looking semiclassical effective field theories, which are actually inconsistent.[citation needed]

Some physicists believe this is a good thing, because it may allow a natural anthropic explanation of the observed values of physical constants, in particular the small value of the cosmological constant.[58][59] The argument is that most universes contain values for physical constants that do not lead to habitable universes (at least for humans), and so we happen to live in the "friendliest" universe. This principle is already employed to explain the existence of life on earth as the result of a life-friendly orbit around the medium-sized sun among an infinite number of possible orbits (as well as a relatively stable location in the galaxy).

Background independence

A separate and older criticism of string theory is that it is background-dependent — string theory describes perturbative expansions about fixed spacetime backgrounds which means that mathematical calculations in the theory rely on preselecting a background as a starting point. This is because, like many quantum field theories, much of string theory is still only formulated perturbatively, as a divergent series of approximations. Although the theory, defined as a perturbative expansion on a fixed background, is not background independent, it has some features that suggest non perturbative approaches would be background-independent — topology change is an established process in string theory, and the exchange of gravitons is equivalent to a change in the background. Since there are dynamic corrections to the background spacetime in the perturbative theory, one would expect spacetime to be dynamic in the nonperturbative theory as well since they would have to predict the same spacetime.

This criticism has been addressed to some extent by the AdS/CFT duality, which is believed to provide a full, non-perturbative definition of string theory in spacetimes with anti-de Sitter space asymptotics. Nevertheless, a non-perturbative definition of the theory in arbitrary spacetime backgrounds is still lacking. Some hope that M-theory, or a non-perturbative treatment of string theory (such as "background independent open string field theory") will have a background-independent formulation.

See also

- Conformal field theory

- Glossary of string theory

- List of string theory topics

- Loop quantum gravity

- Relationship between string theory and quantum field theory

- String cosmology

- Supergravity

- The Elegant Universe

References

- ^ Klebanov, Igor; Maldacena, Juan (2009). "Solving Quantum Field Theories via Curved Spacetimes" (PDF). Physics Today. Retrieved May, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ John H. Schwarz, From Superstrings to M Theory

- ^ Hawking, Stephen (2010). The Grand Design. Bantam Books. ISBN 055338466X.

- ^ Sheldon Glashow. "NOVA – The elegant Universe". Pbs.org. Retrieved on 2012-07-11.

- ^ Sheldon Glashow. NOVA | The Elegant Universe: Series. Pbs.org. Retrieved on 2012-07-11.

- ^ Burt A. Ovrut (2006). "A Heterotic Standard Model". Fortschritte der Physik. 54-(2–3): 160–164. Bibcode:2006ForPh..54..160O. doi:10.1002/prop.200510264.

- ^ a b H. Nastase, More on the RHIC fireball and dual black holes, BROWN-HET-1466, arXiv:hep-th/0603176, March 2006,

- ^ a b Liu, Hong; Rajagopal, Krishna; Wiedemann, Urs (2007). "Anti–de Sitter/Conformal-Field-Theory Calculation of Screening in a Hot Wind". Physical Review Letters. 98 (18). arXiv:hep-ph/0607062. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98r2301L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.182301.

- ^ a b Liu, Hong; Rajagopal, Krishna; Wiedemann, Urs Achim (2006). "Calculating the Jet Quenching Parameter". Physical Review Letters. 97 (18). arXiv:hep-ph/0605178. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..97r2301L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.182301.

- ^ a b H. Nastase, The RHIC fireball as a dual black hole, BROWN-HET-1439, arXiv:hep-th/0501068, January 2005,

- ^ S. James Gates, Jr., Ph.D., Superstring Theory: The DNA of Reality "Lecture 23 – Can I Have That Extra Dimension in the Window?", 0:04:54, 0:21:00.

- ^ Hellerman, Simeon; Swanson, Ian (2007). "Dimension-changing exact solutions of string theory". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2007 (9): 096. arXiv:hep-th/0612051v3. Bibcode:2007JHEP...09..096H. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2007/09/096.

- ^ Aharony, Ofer; Silverstein, Eva (2007). "Supercritical stability, transitions, and (pseudo)tachyons". Physical Review D. 75 (4). arXiv:hep-th/0612031v2. Bibcode:2007PhRvD..75d6003A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.75.046003.

- ^ M. J. Duff, James T. Liu and R. Minasian Eleven Dimensional Origin of String/String Duality: A One Loop Test Center for Theoretical Physics, Department of Physics, Texas A&M University

- ^ Polchinski, Joseph (1998). String Theory, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0521672295.

- ^ The calculation of the number of dimensions can be circumvented by adding a degree of freedom, which compensates for the "missing" quantum fluctuations. However, this degree of freedom behaves similar to spacetime dimensions only in some aspects, and the produced theory is not Lorentz invariant, and has other characteristics that do not appear in nature. This is known as the linear dilaton or non-critical string.

- ^ "Quantum Geometry of Bosonic Strings – Revisited"

- ^ http://physics.usc.edu/~bars/twoTph.htm

- ^ http://phys.org/news98468776.html

- ^ http://www.phy.duke.edu/~muller/Talks/Columbia_100412.pdf

- ^ See, for example, T. Hübsch, "A Hitchhiker’s Guide to Superstring Jump Gates and Other Worlds", in Proc. SUSY 96 Conference, R. Mohapatra and A. Rasin (eds.), Nucl. Phys. (Proc. Supl.) 52A (1997) 347–351

- ^ Randall, Lisa (1999). "An Alternative to Compactification". Physical Review Letters. 83 (23): 4690. arXiv:hep-th/9906064. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..83.4690R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.4690.

- ^ Aspinwall, Paul S.; Greene, Brian R.; Morrison, David R. (1994). "Calabi-Yau moduli space, mirror manifolds and spacetime topology change in string theory". Nuclear Physics B. 416 (2): 414. arXiv:hep-th/9309097. Bibcode:1994NuPhB.416..414A. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(94)90321-2.

- ^ a b c d + Kachru, Shamit; Kallosh, Renata; Linde, Andrei; Trivedi, Sandip (2003). "De Sitter vacua in string theory". Physical Review D. 68 (4). arXiv:hep-th/0301240. Bibcode:2003PhRvD..68d6005K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.68.046005.

- ^ Freivogel, Ben; Kleban, Matthew; Martínez, María Rodríguez; Susskind, Leonard (2006). "Observational consequences of a landscape". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2006 (3): 039. arXiv:hep-th/0505232. Bibcode:2006JHEP...03..039F. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2006/03/039.

- ^ M. Kleban, T. Levi, and K. Sigurdson, Observing the landscape with cosmic wakes, arXiv:1109.3473

- ^ S. Nadis, "How we could see another universe,", June 2009. Astronomy.com. Retrieved on 2012-07-11.

- ^ Polchinski, Joseph. "Introduction to Cosmic F- and D-Strings". arXiv:hep-th/0412244.

- ^ Idem, "Lecture 19 – Do-See-Do and Swing your Superpartner Part II" 0:16:05-0:24:29.

- ^ Idem, Lecture 21, 0:20:10-0:21:20.

- ^ J. Maldacena, The Large N Limit of Superconformal Field Theories and Supergravity, arXiv:hep-th/9711200

- ^ S. S. Gubser, I. R. Klebanov and A. M. Polyakov (1998). "Gauge theory correlators from non-critical string theory". Physics Letters. B428: 105–114. arXiv:hep-th/9802109. Bibcode:1998PhLB..428..105G. doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(98)00377-3.

- ^ Edward Witten (1998). "Anti-de Sitter space and holography". Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics. 2: 253–291. arXiv:hep-th/9802150. Bibcode:1998hep.th....2150W.

- ^ Aharony, O. (2000). "Large N Field Theories, String Theory and Gravity". Phys. Rept. 323 (3–4): 183–386. arXiv:hep-th/9905111. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(99)00083-6.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ N=6 superconformal Chern-Simons-matter theories, M2-branes and their gravity duals

- ^ ntLab: 6d (2,0)-supersymmetric QFT

- ^ Restrictions Imposed by Superconformal Invariance on Quantum Field Theories

- ^ [John Schwarz Dirac Memorial Lecture on superconformal field theories http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fFsOq6a6DaY]

- ^ Recent Results of the MILC research program, taken from the MILC Collaboration homepage

- ^ Sakai, Tadakatsu; Sugimoto, Shigeki (2005). "Low Energy Hadron Physics in Holographic QCD". Progress of Theoretical Physics. 113 (4): 843. arXiv:hep-th/0412141. Bibcode:2005PThPh.113..843S. doi:10.1143/PTP.113.843.

- ^ S. James Gates, Jr., Ph.D., Superstring Theory: The DNA of Reality "Lecture 21 – Can 4D Forces (without Gravity) Love Strings?", 0:26:06-0:26:21, cf. 0:24:05-0:26-24.

- ^ Deligne, Pierre; Etingof, Pavel; Freed, Daniel; Jeffery, Lisa; Kazhdan, David; Morgan, John; Morrison, David; Witten, Edward, eds. (1999). Quantum Fields and Strings: A Course for Mathematicians. Vol. 1. American Mathematical Society. p. 1.

- ^ Hori, Kentaro; Katz, Sheldon; Klemm, Albrecht; Pandharipande, Rahul; Thomas, Richard; Vafa, Cumrun; Vakil, Ravi; Zaslow, Eric, eds. (2003). Mirror Symmetry. American Mathematical Society.

- ^ Frenkel, Igor; Lepowsky, James; Meurman, Arne (1988). Vertex operator algebras and the Monster. Pure and Applied Mathematics. Vol. 134. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-267065-5.

- ^ Dolen, R.; Horn, D.; Schmid, C. (1968). "Finite-Energy Sum Rules and Their Application to πN Charge Exchange". Physical Review. 166 (5): 1768. Bibcode:1968PhRv..166.1768D. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.166.1768.

- ^ Banks, T.; Fischler, W.; Shenker, S. H.; Susskind, L. (1997). "M theory as a matrix model: A conjecture". Physical Review D. 55 (8): 5112. arXiv:hep-th/9610043v3. Bibcode:1997PhRvD..55.5112B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.55.5112.

- ^ Peter Woit Not Even Wrong. Math.columbia.edu. Retrieved on 2012-07-11.

- ^ Lee Smolin. The Trouble With Physics. Thetroublewithphysics.com. Retrieved on 2012-07-11.

- ^ The n-Category Cafe. Golem.ph.utexas.edu (2007-02-25). Retrieved on 2012-07-11.

- ^ John Baez weblog. Math.ucr.edu (2007-02-25). Retrieved on 2012-07-11.

- ^ P. Woit (Columbia University), String theory: An Evaluation,February 2001, arXiv:physics/0102051

- ^ P. Woit, Is String Theory Testable? INFN Rome March 2007

- ^ "String theory is the first science in hundreds of years to be pursued in pre-Baconian fashion, without any adequate experimental guidance", New York Times, 4 January 2005

- ^ "there ain't no experiment that could be done nor is there any observation that could be made that would say, `You guys are wrong.' The theory is safe, permanently safe" NOVA interview

- ^ "String theory [is] yet to have any real successes in explaining or predicting anything measurable" New York Times, 8 November 2005)

- ^ Rovelli, Carlo (2003). International Journal of Modern Physics D [Gravitation; Astrophysics and Cosmology]. 12 (9): 1509. arXiv:hep-th/0310077. Bibcode:2003IJMPD..12.1509R. doi:10.1142/S0218271803004304.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Elias Kiritsis (2007) "String Theory in a Nutshell"

- ^ N. Arkani-Hamed, S. Dimopoulos and S. Kachru, Predictive Landscapes and New Physics at a TeV, arXiv:hep-th/0501082, SLAC-PUB-10928, HUTP-05-A0001, SU-ITP-04-44, January 2005

- ^ L. Susskind The Anthropic Landscape of String Theory, arXiv:hep-th/0302219, February 2003

Further reading

Popular books and articles

- Davies, Paul (1992). Superstrings: A Theory of Everything?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 244. ISBN 0-521-43775-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Gefter, Amanda (2005). "Is string theory in trouble?". New Scientist. Retrieved December 19, 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) – An interview with Leonard Susskind, the theoretical physicist who discovered that string theory is based on one-dimensional objects and now is promoting the idea of multiple universes. - Green, Michael (1986). "Superstrings". Scientific American. Retrieved December 19, 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Greene, Brian (2003). The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions, and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 464. ISBN 0-393-05858-1.

- Greene, Brian (2004). The Fabric of the Cosmos: Space, Time, and the Texture of Reality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 569. ISBN 0-375-41288-3.

- Gribbin, John (1998). The Search for Superstrings, Symmetry, and the Theory of Everything. London: Little Brown and Company. p. 224. ISBN 0-316-32975-4.

- Halpern, Paul (2004). The Great Beyond: Higher Dimensions, Parallel Universes, and the Extraordinary Search for a Theory of Everything. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 326. ISBN 0-471-46595-X.

- Hooper, Dan (2006). Dark Cosmos: In Search of Our Universe's Missing Mass and Energy. New York: HarperCollins. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-06-113032-8.

- Kaku, Michio (1994). Hyperspace: A Scientific Odyssey Through Parallel Universes, Time Warps, and the Tenth Dimension. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 384. ISBN 0-19-508514-0.

- Klebanov, Igor and Maldacena, Juan (January 2009). Solving Quantum Field Theories via Curved Spacetimes. Physics Today.

- Musser, George (2008). The Complete Idiot's Guide to String Theory. Indianapolis: Alpha. p. 368. ISBN 978-1-59257-702-6.

- Randall, Lisa (2005). Warped Passages: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Universe's Hidden Dimensions. New York: Ecco Press. p. 512. ISBN 0-06-053108-8.

- Susskind, Leonard (2006). The Cosmic Landscape: String Theory and the Illusion of Intelligent Design. New York: Hachette Book Group/Back Bay Books. p. 403. ISBN 0-316-01333-1.

- Taubes, Gary (November 1986). "Everything's Now Tied to Strings" Discover Magazine vol 7, #11. (Popular article, probably the first ever written, on the first superstring revolution.)

- Vilenkin, Alex (2006). Many Worlds in One: The Search for Other Universes. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 235. ISBN 0-8090-9523-8.

- Witten, Edward (2002). "The Universe on a String" (PDF). Astronomy Magazine. Retrieved December 19, 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) – An easy nontechnical article on the very basics of the theory.

Two nontechnical books that are critical of string theory:

- Smolin, Lee (2006). The Trouble with Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 392. ISBN 0-618-55105-0.

- Woit, Peter (2006). Not Even Wrong – The Failure of String Theory And the Search for Unity in Physical Law. London: Jonathan Cape &: New York: Basic Books. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-465-09275-8.

Textbooks

- Becker, Katrin, Becker, Melanie, and John H. Schwarz (2007) String Theory and M-Theory: A Modern Introduction . Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-86069-5

- Binétruy, Pierre (2007) Supersymmetry: Theory, Experiment, and Cosmology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850954-7.

- Dine, Michael (2007) Supersymmetry and String Theory: Beyond the Standard Model. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85841-0.

- Paul H. Frampton (1974). Dual Resonance Models. Frontiers in Physics. ISBN 0-8053-2581-6.

- Gasperini, Maurizio (2007) Elements of String Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86875-4.

- Michael Green, John H. Schwarz and Edward Witten (1987) Superstring theory. Cambridge University Press. The original textbook.

- Vol. 1: Introduction. ISBN 0-521-35752-7.

- Vol. 2: Loop amplitudes, anomalies and phenomenology. ISBN 0-521-35753-5.

- Kiritsis, Elias (2007) String Theory in a Nutshell. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12230-4.

- Johnson, Clifford (2003). D-branes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80912-6.

- Vol. 1: An introduction to the bosonic string. ISBN 0-521-63303-6.

- Vol. 2: Superstring theory and beyond. ISBN 0-521-63304-4.

- Szabo, Richard J. (Reprinted 2007) An Introduction to String Theory and D-brane Dynamics. Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-86094-427-7.

- Zwiebach, Barton (2004) A First Course in String Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83143-1. Contact author for errata.

Technical and critical:

- Penrose, Roger (2005). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Knopf. p. 1136. ISBN 0-679-45443-8.

Online material

- Ajay, Shakeeb, Wieland; et al. (2004). "The nth dimension". Retrieved December 16, 2005.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) – A comprehensive compilation of materials concerning string theory, created by an international team of students. - Chalmers, Matthew (2007-09-03). "Stringscape". Physics World. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - Daniel Friedan (2003) “A Tentative Theory of Large Distance Physics,” Journal of High Energy Physics 10: 063. http://arxiv.org/abs/hep-th/0204131. Section 1 contains a sweeping criticism of string theory. "Large distance" encompasses everything from viruses to the cosmos.

- George Gardner (2007-01-24). "Theory of everything put to the test". Newsgroup: tech.blorge.com. ID109828243. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- Harris, Richard (2006-11-07). "Short of 'All,' String Theorists Accused of Nothing". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- Kibble, Tom. "Cosmic strings reborn?". arXiv:astro-ph/0410073. – Invited Lecture at COSLAB 2004, held at Ambleside, Cumbria, United Kingdom, from 10 to 17 September 2004.

- Krauss, Lawrence (2005-11-23). "Theory of Anything?". Slate.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=|publisher=(help) – A criticism of string theory. - Marolf, Don. "Resource Letter NSST-1: The Nature and Status of String Theory". arXiv:hep-th/0311044. – A guide to the string theory literature.

- Minkel, J. R. (2006-03-02). "A Prediction from String Theory, with Strings Attached". Scientific American.

- Schwarz, John H. "Introduction to Superstring Theory". arXiv:hep-ex/0008017. – Surveys basic concepts in string theory. Four lectures, presented at the NATO Advanced Study Institute on Techniques and Concepts of High Energy Physics, St. Croix, Virgin Islands, in June 2000, and addressed to an audience of graduate students in experimental high energy physics.

- Schwarz, John (2001). "Early History of String Theory: A Personal Perspective". Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- David Tong. "Lectures on String Theory". arXiv:0908.0333. – This is a one semester course on bosonic string theory aimed at beginning graduate students. The lectures assume a working knowledge of quantum field theory and general relativity.

- Veneziano, Gabriele (May 2004). "The Myth of the Beginning of Time". Scientific American.

- Witten, Edward (1998). "Duality, Spacetime and Quantum Mechanics". Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics. Retrieved December 16, 2005. – Slides and audio from an Ed Witten lecture introducing string theory and discussein its challenges.

- Woit, Peter (2002). "Is string theory even wrong?". American Scientist. Retrieved December 16, 2005. – A criticism of string theory.

- A website dedicated to creative writing inspired by string theory.

- An Italian Website with various papers in English language concerning the mathematical connections between String Theory and Number Theory.

- Zidbits (2011-03-27). "A Layman's Explanation For String Theory?".

External links

- Why String Theory – an introduction to string theory

- Dialogue on the Foundations of String Theory at MathPages

- Superstrings! String Theory Home Page – Online tutorial

- CI.physics. STRINGS newsgroup – A moderated newsgroup for discussion of string theory (a theory of quantum gravity and unification of forces) and related fields of high-energy physics.

- Not Even Wrong – A blog critical of string theory.

- Superstring Theory Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics

- The Official String Theory Web Site

- The Elegant Universe – A Three-Hour Miniseries with Brian Greene by NOVA (original PBS Broadcast Dates: October 28, 8–10 p.m. and November 4, 8–9 p.m., 2003). Various images, texts, videos and animations explaining string theory.

- Beyond String Theory – A project by a string physicist explaining aspects of string theory to a broad audience.

- Spinning the Superweb: Essays on the History of Superstring Theory – A Science Studies' approach to the history of string theory (an elementary knowledge of string theory is required).