Duke Cunningham

Duke Cunningham | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California's 50th district | |

| In office January 3, 2003 – December 6, 2005 | |

| Preceded by | New District |

| Succeeded by | Brian Bilbray |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California's 51st district | |

| In office January 3, 1993 – January 3, 2003 | |

| Preceded by | District created |

| Succeeded by | Bob Filner |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California's 44th district | |

| In office January 3, 1991 – January 2, 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Jim Bates |

| Succeeded by | Al McCandless |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Randall Harold Cunningham December 8, 1941 Los Angeles, California |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Susan Albrecht (1965-1973, divorced) Nancy Jones (1974-current) |

Randall Harold Cunningham (born December 8, 1941), usually known as Randy or Duke, is a United States Navy veteran and former Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from California's 50th Congressional District from 1991 to 2005.

Cunningham resigned from the House on November 28, 2005, after pleading guilty to accepting at least $2.4 million in bribes and under-reporting his income for 2004. He pleaded guilty to federal charges of conspiracy to commit bribery, mail fraud, wire fraud and tax evasion. On March 3, 2006, he received a sentence of eight years and four months in prison and was ordered to pay $1.8 million in restitution.[1]

Prior to his political career, Cunningham was an officer in the US Navy for 20 years. Together with his Radar Intercept Officer, William P. "Irish" Driscoll, Cunningham became the only navy flying ace from the Vietnam War to obtain five confirmed aerial victories during that conflict, and one of only five U.S. aviators to become an ace during that conflict.[citation needed] To date, Cunningham and Driscoll are the two last aircrew of the United States Navy to achieve "ace" status. Following the war, Cunningham was later an instructor at the U.S. Navy's Fighter Weapons School, better known as TOPGUN, and commanding officer of Fighter Squadron 126 (VF-126), a shore-based adversary squadron at NAS Miramar, California.[2]

Family

Cunningham was born in Los Angeles to Randall and Lela Cunningham, who both moved there from Pennsylvania during the Depression. His father was a truck driver for Union Oil at the time.[3] Around 1945, the family moved to Fresno, California, where Cunningham's father purchased a gas station. In 1953 they moved again, this time to rural Shelbina, Missouri, where his parents purchased and managed the Cunningham Variety Store, a five-and-dime. In Shelbina, Cunningham relished the times he spent hunting pheasant and deer with his father.[4][5]

Cunningham married his first wife, the former Susan Albrecht, in 1965; they met in college and had one adopted son, Todd. Susan filed for divorce and a restraining order in January 1973, based on her claims of emotional abuse, and the divorce was granted nine months later.[6] Cunningham later stated that in that year, his life hit "rock-bottom."[7]

In 1973, he met Dan McKinnon, a publisher and son of former Congressman Clinton D. McKinnon. Dan McKinnon encouraged him to turn his life around, and Cunningham became a born-again Christian.[7][8]

Cunningham met his second wife, Nancy D. Jones, at the Miramar Officers' Club in San Diego and they were married February 16, 1974.[5] Nancy was born in 1952 and is also previously married. In 1976, she filed for divorce and a restraining order, stating that he "is a very aggressive spontaneously assaultive person, and I fear for my immediate physical safety and well being." Nancy later had a change of heart, so at her request, the court dismissed the divorce in January 1977. Nancy's declaration justifying the restraining order has been sealed by court order since 1990, when Duke first ran for congress. They have two daughters, April and Carrie. Dr. Nancy Cunningham is an educator for the Encinitas school district.[6]

Education and military service

Randall Harold Cunningham | |

|---|---|

Duke Cunningham | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1967–1987 |

| Rank | Commander |

| Battles / wars | Vietnam War |

| Awards | Navy Cross Silver Star (2) Purple Heart, "Flying Ace" status |

| Other work | U.S. Representative, California |

Cunningham graduated from Shelbina High School in 1959. He attended Kirksville Teacher's College for one year before transferring to the University of Missouri in Columbia, Missouri. Cunningham graduated with a bachelor's degree in education and physical education in 1964; he obtained his M.A. in education the following year. He was hired as a physical education teacher and swimming coach at Hinsdale Central High School where he stayed for one year. Two members of his swim team competed in the 1968 Olympics, where they earned a gold and a silver medal. Cunningham joined the United States Navy in 1967.[5]

During his service, Cunningham and his Radar Intercept Officer (RIO) "Irish" Driscoll became the only Navy aces in the Vietnam War, flying an F-4 Phantom II from aboard aircraft carriers, and recording five confirmed kills. Though he did train with the instructor pilots of the department within fighter squadron VF-121 "Pacemakers" that later became the US Navy's Fighter Weapon School, he was not a graduate of TOPGUN, nor was he selected, at least officially, to participate in actual TOPGUN training. He was undergoing F-4 conversion training with VF-121 at the time, in the late 1960s.

Cunningham downed a MiG-17 which was supposedly piloted by North Vietnam Air Force fighter ace Col. Nguyen Toon, aka, "Colonel Tomb". Although "Colonel Tomb" was actually a myth, a North Vietnamese Air Force pilot from the 921st Fighter Regiment named Nguyen Van Coc[9] did score 9 aerial victories during the war, and his aircraft (number 4326) was adorned with 13 air combat kills. Photographs of this particular MiG-21 had been circulated in numerous western publications during the late 1960s, which likely influenced the growth of the legendary "Colonel Tomb". Like many pilots on both sides, they flew what aircraft were available, and the 13 kill markings on MiG-21 #4326 were from several pilots within the 921st Fighter Regiment, including one aerial victory by Van Coc himself on May 7, 1968, when he downed an F-4 Phantom (BuNo 151485).[10]

Like many fighter pilots in most countries, they held a high regard for tough competition and the North Vietnamese Air Force, no doubt, helped perpetuate the myth of "Colonel Toon", or "Tomb".[11] "Colonel Toon" was not only skilled but unorthodox, as Cunningham found out, when the Navy pilot made an elementary tactical error engaging him. Cunningham climbed steeply, and the MiG pilot surprised Cunningham by climbing as well. The resulting dogfight became extended, with both aircraft engaging in a series of vertical rolling scissors maneuvers. Remembering his training with VF-121, Cunningham finally forced the MiG out ahead of him and destroyed it with an AIM-9 Sidewinder missile.

Cunningham was reportedly almost court-martialed while an instructor at TOPGUN for allegedly breaking into his commanding officer's office to compare his record and fitness reports with those of his colleagues — a charge denied by Cunningham, but supported by two of his superior officers at the time.[2][12] Regardless of the controversy, there was little doubt about Cunningham's piloting abilities. He was one of the most highly decorated United States Navy pilots in the Vietnam War, receiving the Navy Cross once, the Silver Star twice, the Air Medal 15 times, and the Purple Heart for wounds he received under enemy fire.

After returning from Vietnam in 1972, he became an instructor at the Navy's TOPGUN school for fighter pilots at Naval Air Station Miramar in San Diego.[2]

Cunningham was a commentator on the History Channel program "Dogfights: The Greatest Air Battles", in the Vietnam War segment, where he discussed his experiences as a fighter pilot. The episode originally aired September 16, 2005. Another interview with Cunningham was featured on the 1987 PBS broadcast of the NOVA special "Top Gun And Beyond", during which he recounted his engagement with the mysterious aviator known only by the name "Colonel Tomb".

In 1985, Cunningham earned an MBA from National University. He retired from the Navy with the final rank of Commander in 1987, settling in Del Mar, a suburb of San Diego. He became nationally known as a CNN commentator on naval aircraft in the run-up to the Persian Gulf War.[citation needed]

Political career

Cunningham's visibility as a CNN commentator led several Republican leaders to approach him about running in what was then the 44th District, one of four that divided San Diego. The district had been held for eight years by Democrat Jim Bates, and was considered the most Democratic district in the San Diego area. However, Bates was bogged down in a scandal involving charges of sexual harassment. Cunningham won the Republican nomination in 1990 and hammered Bates about the scandal, promising to be "a congressman we can be proud of." He won by just one percentage point, meaning that the San Diego area was represented entirely by Republicans for only the second time since the city was split into two districts after the 1960 census.

Congressional freshmen usually do not get much media attention outside of their home districts or states, but Cunningham's status as a Vietnam War hero made him an exception. Colleagues and the media admired him for his special knowledge of the armed forces: he played an important role in the debate on whether to use military force to make Iraq end its occupation of Kuwait.[12] Guy Vander Jagt of Michigan, longtime chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee, said that Cunningham had considerable "drawing power" and was treated as a celebrity by his fellow Republicans.[13]

After the 1990 census, redistricting renumbered the 44th District as the 51st and created the 50th District, splitting off a significant portion of San Diego County. At the same time, the 51st added several areas of heavily Republican North San Diego County. The new district included the home of Bill Lowery, a fellow Republican who had represented most of the other side of San Diego for the past 12 years. They faced one another in the Republican primary. Despite Lowery's seniority, his involvement in the House banking scandal hurt him. Cunningham repeated his promise from 1990 to be "a congressman we can be proud of." As polls showed Cunningham with a substantial lead, Lowery dropped out of the primary race, effectively handing Cunningham the nomination. He breezed to victory in November.

Even though the district (renumbered as the 50th after the 2000 census) is not nearly as conservative as the other two Republican-held districts in the San Diego area, Cunningham was reelected six times with no less than 55 percent of the vote.

Cunningham was a member of the Appropriations and Intelligence committees, and chaired the House Intelligence Subcommittee on Human Intelligence Analysis and Counterintelligence during the 109th Congress. He was considered a leading Republican expert on national security issues. He was also a champion of education, using his position on the Appropriations Education Subcommittee to steer federal dollars to schools in San Diego. After surgery for prostate cancer in 1998, he became a champion of early testing for the disease.

Cunningham was known for making intemperate outbursts. For example:

- Making a comment about gay Congressman Barney Frank, where he called the rectal examination for prostate cancer "just not natural, unless maybe you’re Barney Frank."[14]

- Displaying his middle finger to a constituent and "for emphasis, [shouting] the two-word meaning of his one-finger salute" during an argument over military spending.[12][15]

- Suggesting that the Democratic House leadership should be "lined up and shot" — a call he'd previously made about Vietnam War protesters.[12]

- Referring to gay soldiers as "homos" on the floor of the House of Representatives when he said backers of an environmental amendment were "...the same people that would...put homos in the military."[14] Congresswoman Pat Schroeder asked if he would yield the floor, but Cunningham told her, "No, I will not." When Congressman Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist, attempted to object, Cunningham said, "Sit down, you socialist."[16] He later apologized for his comments.[14]

In the Washingtonian feature "Best & Worst of Congress" of 2004, Cunningham was rated (along with four other House members) as "No Rocket Scientist" by a bipartisan survey of Congressional staff.[17]

While Cunningham said that "I cut my own rudder" on issues,[12] he had a very conservative voting record.[18] He was often compared by liberal interest groups to former congressman Bob Dornan, with some justification; both are ardent conservatives, both are former military pilots, and both have become infamous for outbursts against perceived enemies. In 1992, Cunningham, along with Dornan and fellow San Diego Republican Duncan Hunter, challenged the patriotism of then-Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton before a near-empty House chamber, but still viewed by C-SPAN viewers.[12]

In September 1996 Cunningham criticized President Clinton for appointing judges who were "soft on crime". "We must get tough on drug dealers," he said, adding that "those who peddle destruction on our children must pay dearly."[19] He favored stiff drug penalties[20] and voted for the death penalty for major drug dealers.[21]

Four months later, his son Todd was arrested for helping to transport 400 pounds (181 kg) of marijuana from Texas to Indiana. Todd Cunningham pleaded guilty to possession and conspiracy to sell marijuana.[22] At his son's sentencing hearing, Cunningham fought back tears as he begged the judge for leniency (Todd was sentenced to two and a half years in prison, in part because he tested positive for cocaine three times while on bail).[21] Cunningham's press secretary responded to accusations of double standards with: "The sentence Todd got had nothing to do with who Duke is. Duke has always been tough on drugs and remains tough on drugs."[20]

Legislative achievements

Cunningham was the lead sponsor of the Shark Finning Prohibition Act, which banned the practice of shark finning in all US waters and pushed America to the lead on efforts to ban shark finning worldwide. For his efforts Cunningham was named as a "Conservation Hero" by the Audubon Society and the Ocean Wildlife Campaign.

Cunningham co-sponsored, along with Democrat John Murtha, the so-called "Flag Desecration Amendment", which would add the following sentence to the Constitution of the United States

- "The Congress shall have power to prohibit the physical desecration of the Flag of the United States."

The proposed amendment has passed the House many times, but narrowly missed the requisite 2/3 majority vote for passage in the Senate.

Cunningham was the driving force behind the Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act which was passed and signed into law by President George W. Bush in July 2004. The law grants the authority to non-federal law enforcement officers from any jurisdiction to carry a firearm anywhere within the jurisdiction of the United States.

Scandals and corruption

Allegations

In June 2005 it was revealed that a defense contractor, Mitchell Wade, founder of the defense contracting firm MZM Inc. (since renamed Athena Innovative Solutions Inc.), bought Cunningham's house in Del Mar for $1,675,000. A month later, Wade placed it back on the market where it remained unsold for 8 months until the price was reduced to $975,000. Cunningham was a member of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee; soon after the purchase, Wade began to receive tens of millions of dollars worth of defense and intelligence contracts. Cunningham claimed the deal was legitimate, adding, "I feel very confident that I haven't done anything wrong."[23]

Later in June, it was further reported that Cunningham lived in a yacht aptly named the "Duke Stir" while he was in Washington. The yacht was owned by Wade; Cunningham paid only for maintenance.[24] An article in the San Diego Union Tribune newspaper, reported that Cunningham liked to invite women to his yacht. Two of them said that he would change into pajama bottoms and a turtleneck sweater to entertain them with chilled champagne by the light of his favorite lava lamp.[25] The Federal Bureau of Investigation launched an investigation regarding the real estate transaction. His home, MZM corporate offices, and Wade's home were all simultaneously raided by several federal agencies with warrants on July 1, 2005.[26]

On July 14, Cunningham announced he would not run for a ninth term in 2006, saying that while he believed he'd be cleared of any wrongdoing, he could not defend himself and run for reelection at the same time. He admitted to displaying "poor judgment" when he sold his house to Wade.[27]

Besides Wade, the three other co-conspirators are: Brent R. Wilkes, founder of San Diego-based ADCS Inc.; New York businessman Thomas Kontogiannis (whom U.S. Coast Guard records show was involved in a questionable boat deal with Cunningham); and John T. Michael, Kontogiannis' nephew (the owner of a New York-based mortgage company, Coastal Capital Corp. Property records show the company made $1.15 million in real estate loans to Cunningham, two of which were used in the purchase of his Rancho Santa Fe mansion. Court records show that Wade paid off one of those loans).[28]

In 1997, Cunningham pushed the Pentagon into buying a $20 million document-digitization system created by ADCS Inc., one of several defense companies owned by Wilkes. The Pentagon did not want to buy the system. When it had not done so three years later, Cunningham angrily demanded the firing of Lou Kratz, an assistant undersecretary of defense he held responsible for the delays.[13] It later emerged that Wilkes reportedly gave Cunningham more than $630,000 in cash and favors.[29]

Cunningham was also criticized for selling merchandise on his personal website,[30] such as a $595 Buck knife featuring the official Congressional seal.[31][32] He failed to obtain permission to use the seal, which is a federal offense.[33]

On April 27, 2006, months after his guilty plea, Scot J. Patrow, writing for the Wall Street Journal, reported that, in addition to all the favors, gifts and money Cunningham received from defense contractors who wanted his help in obtaining contracts, Cunningham may have been provided with prostitutes, hotel rooms and limousines.[34]

Duke Cunningham | |

|---|---|

| Occupation(s) | Politician, former Congressman |

| Criminal status | Imprisoned in Tucson |

| Criminal charge | Conspiracy to commit bribery, mail fraud, wire fraud and tax evasion |

| Penalty | 100 months (8 years, 4 months) imprisonment |

Plea agreement

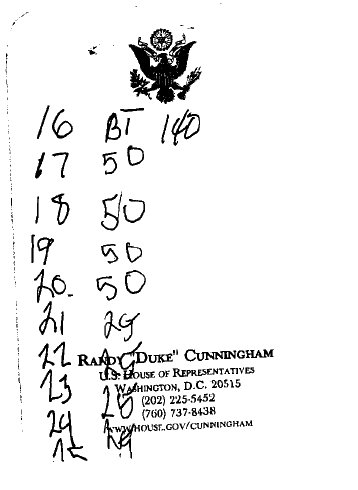

On November 28, 2005, Cunningham pleaded guilty to tax evasion, conspiracy to commit bribery, mail fraud and wire fraud in federal court in San Diego. Among the many bribes Cunningham admitted receiving were the house sale at an inflated price, the free use of the yacht, a used Rolls-Royce, antique furniture, Persian rugs, jewelry, and a $2,000 contribution for his daughter's college graduation party.[35] Cunningham's attorney, Mark Holscher, later said that the government's evidence was so overwhelming that he had no choice but to recommend a guilty plea.[36] With the plea bargain, Cunningham faced a maximum of 10 years; had he fought the charges, Cunningham risked spending the rest of his life in prison.

As part of his guilty plea, Cunningham agreed to forfeit his $2.55 million home in Rancho Santa Fe, which he bought with the proceeds of the sale of the Del Mar house. Cunningham initially tried to sell the Rancho Santa Fe house, but federal prosecutors moved to block the sale after finding evidence it was purchased with Wade's money. (Wade, with others, even paid off the balance Cunningham owed on the mortgage.) Cunningham will also forfeit more than $1.8 million in cash, antiques, rugs, and other items.

Also as part of the plea agreement, Cunningham agreed to help the government in its prosecution of others involved in the defense contractor bribery scandal. However, news reports surfaced stating that Cunningham was not cooperating with investigators despite the agreement.[37] A week later, Cunningham, through his lawyer, announced that he was ready to cooperate.[38]

Resignation

Cunningham announced that he would resign from the House at a press conference just after entering his plea. He submitted his official resignation letter to the Clerk of the House and to California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger on December 6, 2005.[39]

Had Cunningham declined to resign, his role in Congress would have been very limited, as House rules do not allow members convicted of felonies to vote or participate in committee work pending an investigation by the Ethics Committee.[40] It is very likely that he would have been expelled from the House, as happened with Democrat James Traficant three years earlier. Under Republican caucus rules, he would have lost his subcommittee chairmanship.[41]

In marked contrast to his defiant stand earlier in the year, Cunningham appeared very contrite, sullen and overcome by emotion when he read his prepared statement announcing that he was stepping down:

When I announced several months ago that I would not seek re-election, I publicly declared my innocence because I was not strong enough to face the truth. So, I misled my family, staff, friends, colleagues, the public — even myself. For all of this, I am deeply sorry. The truth is — I broke the law, concealed my conduct, and disgraced my high office. I know that I will forfeit my freedom, my reputation, my worldly possessions, and most importantly, the trust of my friends and family. ... In my life, I have known great joy and great sorrow. And now I know great shame. I learned in Viet Nam that the true measure of a man is how he responds to adversity. I cannot undo what I have done. But I can atone. I am now almost 65 years old and, as I enter the twilight of my life, I intend to use the remaining time that God grants me to make amends.[42]

Despite his guilty plea, Cunningham may still receive a pension for his 21 years of service in the navy and almost 15 years in Congress. While federal law only allows the government to strip pensions from federal employees guilty of treason, perjury or trading secrets with the enemy, San Diego benefits expert Robert Goldstein told the San Diego Union-Tribune that it is possible the government could still try to take the money from Cunningham.[43]

Reactions

Local

Darrell Issa, a Republican who represents the neighboring 49th District, said after Cunningham's plea that he'd been waiting for Cunningham to explain his behavior "in a way that made sense to us" and that Cunningham's behavior "fell below the standard the public demands of its elected representatives."[44] Duncan Hunter, the other Republican then representing the San Diego area, said on November 30 that he and Cunningham spent the rest of November 28 in prayer and that Cunningham wanted to "serve those who are suffering (and) to begin his long road of atonement" for his crimes.[45] Many of Cunningham's staffers were stunned at the extent of their boss's crimes.[46]

Union-Tribune columnist George Condon suggested in a December 1 column that Cunningham's actions "may have put ... troops at greater risk by judging contracts more for what they would do for him than for the military."[25]

Francine Busby, Cunningham's Democratic challenger in 2004 and the Democratic candidate for the 50th District in the runoff election to fill Cunningham's vacancy, called November 28 "a sad day for the people" and called for support for her proposed ethics reform bill, the "Clean House Act", saying that "our government in Washington is broken."[47]

National

In an editorial on November 29, the Washington Post called the Cunningham affair "the most brazen bribery conspiracy in modern congressional history."[48] Later that day, President George W. Bush called Cunningham's actions "outrageous" at a press briefing in El Paso. He also said that Cunningham should "pay a serious price" for his crimes.[36] House Speaker Dennis Hastert said in a December 6 statement that Cunningham was a "war hero"; but that he broke "the public trust he has built through his military and congressional career."[49] Several of Cunningham's former colleagues have donated the campaign contributions he had given them, to charity .[50]

On February 9, 2006, Senator John Kerry introduced a bill, the "Federal Pension Forfeiture Act" (nicknamed the "Duke Cunningham Act"), to prevent lawmakers who have been convicted of official misconduct from collecting taxpayer funded pensions.[51]

Sentencing

On March 3, 2006, U.S. District Judge Larry A. Burns sentenced Cunningham to 100 months (eight years and four months) in prison.[1] Federal prosecutors pushed for the maximum sentence of ten years, but Cunningham's defense lawyers said that at 64 years old and with prostate cancer, Cunningham would likely die in prison if he received the full sentence.[52][53] Judge Burns cited his military service in Vietnam, age, and health as the reason the full ten years was not imposed. Prosecutors announced that they were satisfied with the sentence, which is the longest jail term ever given to a former Congressman.[54]

On the day of sentencing, Cunningham was 90 pounds (41 kg) lighter than when allegations first surfaced 9 months earlier. After receiving his sentence, Cunningham made a request to see his 91-year-old mother one last time before going to prison. "I made a very wrong turn. I rationalized decisions I knew were wrong. I did that, sir," Cunningham said. The request was denied, and Burns remanded him immediately upon rendering the sentence.[55] Cunningham was incarcerated in the minimum security satellite camp at the U.S. Penitentiary at Tucson, Arizona.[56] He was assigned federal inmate number 94405-198 and his scheduled release date is June 4, 2013.[57] He spent his time at the prison teaching fellow inmates to obtain their GED,[58] as well as claiming to be a prison reform advocate.[59] As of January 2013, Cunningham was released to a half-way house in New Orleans, Louisiana, where he is slated to remain until his scheduled release pending no disciplinary infractions.

Aftermath

2005

- Almost as soon as Cunningham pled guilty, Intelligence Committee chairman Pete Hoekstra of Michigan (who represented Guy Vander Jagt's former district at the time) announced his panel would investigate whether Cunningham used his post on that committee to steer contracts to favored companies. Hoekstra said that Cunningham "no longer gets the benefit of the doubt" due to his admission to "very, very serious" crimes. "We need to look at worst-case scenarios," he added. He also shut off Cunningham's access to classified information. While Hoekstra does not believe that Cunningham improperly influenced the Intelligence Committee's work, a committee spokesman said that he wanted to make sure its work stayed on the level.[60]

- Bill Young of Florida, chairman of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee and former chairman of the full Appropriations Committee, said that he planned to review Cunningham's requests for defense projects. While he felt most of the requests were legitimate and supported by the Pentagon, he said that he needed to be "doubly sure that anything shaky is not going to stay in."[61]

- On December 14, prosecutors in former House Majority Leader Tom DeLay's money laundering trial revealed that they are looking into ties between Wilkes and DeLay. One of Wilkes' companies donated $15,000 to DeLay's PAC, Texans for a Republican Majority. Wilkes also hired a consulting firm that employed DeLay's wife, Christine.[62]

2006

- On January 6, Time reported that Cunningham cooperated with law enforcement by wearing a concealed recording device (a "wire") while meeting with associates prior to his guilty plea. It is not known whom he met with while wired, but there is speculation Cunningham's misdeeds were not isolated instances and his case could reveal a larger web of corruption.[63]

- On February 24, Mitchell Wade pleaded guilty to paying Cunningham more than $1 million in bribes in exchange for millions more in government contracts.[64]

- In March, it was revealed that CIA officials have opened an investigation into the CIA's No.3 official, Kyle Foggo, and his relationship with Wilkes, "one of his closest friends," according to the article. Foggo has said that all of the contracts he oversaw were properly awarded and administered.[65]

- A special election to fill the vacancy left by Cunningham took place on April 11. No candidate obtained the majority necessary to win outright, so a runoff election was scheduled for June 6 between Democrat Busby and Republican Brian Bilbray, who had represented the nearby 49th District from 1995 to 2001.

- On April 17, the staffs of The San Diego Union-Tribune and Copley News Service were awarded the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting for their investigative work in uncovering Cunningham's crimes.[66]

- On May 12, FBI officials raided the Vienna, Virginia, home of former CIA official Kyle "Dusty" Foggo in connection with the scandal.[67]

- On June 6, Republican Brian Bilbray won the runoff election for Cunningham's seat, narrowly defeating Democrat Francine Busby.[68]

- On November 7, Bilbray beat Busby again and retained his seat in the House.[69]

2007

- In January, the Justice Department requested the resignation of U.S. Attorney Carol Lam, who led the corruption prosecution of Cunningham.[70][71] For further information see Dismissal of U.S. attorneys controversy.

- On February 13, former CIA executive director Kyle Foggo was charged with fraud and other offenses in the Cunningham corruption investigation. The indictment also named Brent R. Wilkes and John T. Michael.

2010

- During June 2010, Cunningham submitted a handwritten three-page letter to sentencing Judge Larry Burns, complaining that the IRS is 'killing' him by seizing all his remaining savings and his Congressional and navy pensions, penalties he feels are not warranted under his plea agreement. Burns wrote back on 4 August 2010, stating that the agency is collecting back taxes, interest, and penalties on the bribes Cunningham received in 2003 and 2004; thus, there is no action for Burns to take.[72]

- In November, Wilkes' lawyers filed documents in court in a bid to gain a re-trial that included statements from Cunningham saying "Wilkes never bribed me".[73] Cunningham is quoted as saying any meals, trips or gifts from Wilkes to him were merely gifts between long-time friends, not bribes. Cunningham also stated that he had been coached by prosecutors to avoid responding to questions where his version of the facts differed from the prosecutors' theory. Cunningham also denied having made statements attributed to him by federal agents and prosecutors. Notably he denied having sex with any prostitute on a trip to Hawaii and explained that at the time he was impotent due to treatment for prostate cancer.

"The Untold Story of Duke Cunningham"

In April 2011, Cunningham sent a ten page typewritten document pleading his case to USA Today, the Los Angeles Times, Talking Points Memo, and San Diego CityBeat. He titled the document "The Untold Story of Duke Cunningham."[74] In the document, Cunningham says that because Judge Larry A. Burns has declared his case closed, he is now offering to speak to the media, which have "inundated" him with inquiries since 2004. According to CityBeat, in the statement, Cunningham claims that he was "doped up on sedatives" and made his plea knowing that it was "90 to 95% untrue."[75][76]

RELEASED by Feds

On June 4th, 2013, Cunningham, 71, was released from home confinement, said Chris Burke, a spokesman for the Federal Bureau of Prisons who declined to say where or explain the circumstances, citing privacy and safety concerns. Typically authorities meet an inmate at home, work or mutually agreeable place to make the release official.

Cunningham told a federal judge last year that he planned to live near his mother and brother in a remote part of Arkansas, writing books in a small cabin. But in a brief interview with The Associated Press in April, he said he might settle with military friends in Florida, where he would write his memoirs.

"I'm like a tenderfoot in the forest," he said. "I'm just unsure where to find a branch to sit on."

Cunningham, who had his sentence cut 392 days for good behavior, wrote the judge last year that he would live on $1,700 a month after his release, saying the IRS "has me poor for the rest of my life." He portrayed the loss of his home and other property as an example of how veterans are mistreated.

"This dark period in my life is about to get a little lighter but do not think it will ever get sunny," he wrote.

In his letter, Cunningham pleaded for a gun permit, saying he longed to hunt in Arkansas. Burns denied the request as being beyond the scope of his authority.

See also

References

- ^ a b Perry, Tony (2006-03-03). "Cunningham Receives Eight-Year Sentence". Los Angeles Times. OCLC 3638237.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c http://legacy.signonsandiego.com/news/politics/20060115-9999-lz1n15legend.html

- ^ California Birth certificate 41-118503

- ^ Pae, Peter (2005-12-09). "Hard-charging Cunningham fell from a lofty perch". Los Angeles Times. OCLC 3638237. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Defendant Cunningham's Sentencing Memorandum, Case 05-CR-2137 (LAB), February 2005"

- ^ a b Dodge, Dani (2006-02-12). "Standing in an unwelcome spotlight". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-1 accessdate=2006-02-19. OCLC 55506628.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|page=(help) - ^ a b Dodge, Dani (2006-02-12). "In disgrace, but not all alone; On ranch, old friend again offers shelter from storm". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. B-1. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-02-20.

- ^ Cunningham, Randy (1989-03-01) [1983-12-01]. Fox Two: The Story of America's First Ace in Vietnam. Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-35458-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Toperczer, Ivan (2001). MiG-21 Units of the Vietnam War. Osprey Publishing Limited. p. 34, plate 5. ISBN 978-1-84176-263-0.

- ^ Toperczer, p. 91, plate 5.

- ^ Hall, George (1987). Top Gun: The Navy's Fighter Weapons School. Presidio Press.

- ^ a b c d e f Braun, Gerry (2005-07-15). "Ex-Navy ace always ready for a fight". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-9. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2005-12-04.

- ^ a b Pae, Peter; Perry, Tony; and Simon, Richard (2005-12-05). "Cunningham's Fall From Grace, Power". Los Angeles Times. p. A-1. OCLC 3638237. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Chibbaro Jr., Lou (2003-07-04). "Birch denies speech outed anti-gay congressman". Washington Blade. OCLC 7955665. Retrieved 2005-12-07.

- ^ Wilkie, Dana (1998-09-09). "Cunningham account of vulgar gesture disputed". The San Diego Union-Tribune. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ^ "Congressional Record Volume 141, Number 78". US Government Printing Office. 11 May 1995. p. H4837. OCLC 2437919. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ "Best & Worst of Congress". Washingtonian. 2004-09. OCLC 1680831. Retrieved 2005-05-03.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ On The Issues. "Duke Cunningham on the Issues". Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ Cunningham, Randy "Duke" (1996-09-24). "A call to arms against youth drug abuse". The San Diego Union-Tribune. pp. B–6–7. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-05-07.

- ^ a b Schlosser, Eric (2007-12-05). "The Politics Of Pot: A Government In Denial". Rolling Stone. OCLC 1787396. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ^ a b Murphy, Bill (2006-05-07). "Son of lawmaker sentenced to prison". The San Diego Union-Tribune. pp. B–1, B-10. OCLC 55506628.

- ^ Powell, Ronald W. (2006-02-20). "In disgrace, but not all alone". The San Diego Union-Tribune. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

- ^ Stern, Marcus (2005-06-12). "Lawmaker's home sale questioned". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-1. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2005-06-13.

- ^ Bennett, William Finn (2005-06-16). "Yacht 'Duke Stir' owned by defense contractor docked at Cunningham's slip". North County Times. OCLC 34056580. Retrieved 2005-06-16.

- ^ a b Condon Jr., George E. (2005-12-01). "Congressman's betrayal of troops called greatest sin". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-21. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2005-12-03.

- ^ Walker, Mark (2005-07-01). "Feds raid Cunningham home, MZM offices and boat". North County Times. OCLC 34056580. Retrieved 2005-07-05.

- ^ Bennett, William Finn (2005-07-14). "Cunningham says he will step down at end of term". North County Times. OCLC 34056580. Retrieved 2006-04-27.

- ^ Bennett, William Finn (2006-03-06). "What's next in Cunningham bribery saga?". North County Times. OCLC 34056580. Retrieved 2006-03-07.

- ^ Calbreath, Dean and Kammer, Jerry (2005-12-04). "Contractor 'knew how to grease the wheels'". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-1. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-04-23.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cunningham's personal website via Wayback Machine

- ^ Buck knife offer on Cunningham's website, via Wayback machine

- ^ Walker, Mark (2005-06-29). "Use of congressional seal on knife questioned". North County Times. OCLC 34056580. Retrieved 2006-04-23.

- ^ : Use of likenesses of the great seal of the United States, the seals of the President and Vice President, the seal of the United States Senate, the seal of the United States House of Representatives, and the seal of the United States Congress

- ^ Patrow, Scot J. (2006-04-27). "Prosecutors May Widen Congressional-Bribe Case; Cunningham Is Suspected Of Asking for Prostitutes; Were Others Involved?". The Wall Street Journal. p. A-6. OCLC 4299067. Retrieved 2006-05-01.

- ^ "Plea Agreement by Randy "Duke" Cunningham and the U.S. Attorney". 2005. Retrieved 2005-12-05.

- ^ a b Soto, Onell R. (2005-11-30). "'Overwhelming case' forced Cunningham to accept deal". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-1. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2005-12-05.

- ^ "'Despite Plea Bargain, Cunningham Not Cooperating: Gwin Troubled By Lack Of Assistance'". 10 News. 2006-05-10. Retrieved 2006-05-11.

- ^ Walker, Mark (2006-05-18). "'Another probe in Cunningham case'". North County Times. OCLC 34056580.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Cantlupe, Joe (2005-12-06). "Cunningham resignation formally submitted to House". The San Diego Union-Tribune. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ The United States Congress (2005). "Rule XXIII — Code of Official Conduct (10)". Rules of the 109th Congress. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ US Government Printing Office (2003). "Chap. 25, Sec. 26: Deprivation of Status; Caucus Rules (par. 3)". A Guide to the Rules, Precedents and Procedures of the House. p. 522. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ Cunningham, Randy "Duke" (2005). "Statement by Randy "Duke" Cunningham" (PDF). O’Melveny & Myers. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ Soto, Onell R. (2005-12-01). "Experts say Cunningham likely to get retirement pay". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-20. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2005-12-05.

- ^ "Rep. Issa Statement On Cunningham Guilty Plea" (Press release). Office of Congressman Darrell Issa. 2005-11-28. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ Cantlupe, Joe (2005-11-30). "Hunter consoling his former colleague". The San Diego Union-Tribune. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ Cantlupe, Joe (2005-12-30). "Cunningham staff devastated at extent of corruption; Aides 'all shocked about how deep this went'". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-16. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ "Francine Busby calls Cunningham Resignation "Sad day for the people"" (Press release). Francine Busby for Congress. 2005-11-28.

{{cite press release}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Brazen Conspiracy". Washington Post. 2005-11-29. p. A-20. Retrieved 2005-11-30.

- ^ Walker, Mark (2005-12-06). "House speaker says Cunningham faces 'serious consequences'". North County Times. OCLC 34056580. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ Wilkie, Dana (2005-12-08). "Lawmakers shed cash tied to two contractors". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-1. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ Klein, Rick (2006-02-09). "Kerry bill to target legislators convicted of misconduct". The Boston Globe. p. A-8. OCLC 1536853. Retrieved 2006-02-09.

- ^ Walker, Mark (2006-02-18). "Feds seek 10-year prison term for Cunningham". North County Times. OCLC 34056580.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Walker, Mark (2006-02-18). "Defense: 'Duke' may die in prison". North County Times. OCLC 34056580.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Crooked congressman going to prison". CNN. 2006-03-03. Retrieved 2006-03-03.

- ^ Hettena, Seth (2006-03-03). "Former Congressman Gets Eight-Plus Years". Associated Press.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Cunningham Moving to Arizona Prison". Washington Post. 2007-01-05. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ "Inmate Locator: Randall Harold Cunningham". Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^ "From Tucson With Love: Checking in with Duke Cunningham halfway through his federal prison sentence". San Diego CityBeat. August 11, 2010.

- ^ "City Beat: Duke Cunningham becomes an educator behind bars | UTSanDiego.com". Signonsandiego.com. 2010-08-11. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ Miller, Greg (2005-11-30). "House Intelligence Panel to Probe Cunningham". Los Angeles Times. OCLC 3638237.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Cunningham's work on panel to be reviewed". The San Diego Union-Tribune. 2005-12-01. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ Gamboa, Suzanne (2005-12-13). "Prosecutor subpoenas Cunningham-related companies in Texas case". Associated Press. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ Burger, Timothy J. (2006-01-06). "Disgraced Congressman 'Wore a Wire'". TIME. OCLC 1767509. Retrieved 2006-01-06.

- ^ Lewis, Finlay; Kammer, Jerry and Cantlupe, Joe (2006-02-25). "Contractor admits bribing Cunningham". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-1. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-04-22.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bennett, William Finn (2006-03-06). "What's next in Cunningham bribery saga?". North County Times. Retrieved 2006-03-07.

- ^ McDonald, Jeff (2006-04-18). "U-T, Copley News win Pulitzer Prize". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-1. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-04-26.

- ^ Mark Mazzetti, David Johnston (2006-05-12). "C.I.A. Aide's House and Office Searched". The New York Times. p. A-10. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved 2006-05-12.

- ^ LaVelle, Philip J. and Dani Dodge (2006-06-07). "Bilbray edges out Busby". The San Diego Union-Tribune. OCLC 55506628. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ^ Britton,Joe and Thorne,Joyce (2006-11-08). "Bilbray defeats Busby". North County Times. OCLC 34056580. Retrieved 2006-11-08.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eggen, Dan (2007-01-19). "Prosecutor Firings Not Political, Gonzales Says". Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ^ Johnston, David (2007-01-17). "Justice Dept. Names New Prosecutors, Forcing Some Out". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Rachel Slajda September 8, 2010, 4:36 PM (2010-09-08). "Duke Cunningham To Judge: You And The IRS 'Have Killed Me' | TPMMuckraker". Tpmmuckraker.talkingpointsmemo.com. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cunningham says he didn't take bribes from contractor | UTSanDiego.com". Signonsandiego.com. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ Moran, Greg (April 7, 2011). "Duke Cunningham pleads case from prison". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ Maass, Dave (April 6, 2011). "'The Untold Story of Duke Cunningham'". San Diego CityBeat. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ Cunningham, Randy "Duke" (April 2011). "Untold Story of Duke Cunningham PDF" (PDF). San Diego CityBeat. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ AP article June 4th, 2013 by Elliot Spagat

External links

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- The San Diego Union-Tribune's coverage of the Cunningham scandal

- Washington Post Express interview with the authors of "The Wrong Stuff" about Cunningham and Washington's culture of corruption

- PAC donors, Indiv donors, Personal Financial Disclosures, Campaign Disbursements, at PoliticalMoneyLine

- Archive of Cunningham's commerce website, topguninc.com (deactivated June 2005)

- Congressman's career buried by blizzard of questions on actions San Diego Union-Tribune, July 15, 2005.

- Duke Cunningham: First and Last Surrender (FlashReport, November 30, 2005)

- DeLay's prosecutors dig deeper into California

- Sourcewatch.org article on Duke Cunningham

Documents

- Prosecutor's allegations against Cunningham

- Plea agreement (November 23, 2005)

- Cunningham's resignation statement (Union-Tribune, November 28, 2005)

- Cunningham's Sentencing Memorandum (February 17, 2006)

- 1941 births

- American members of the Churches of Christ

- American prisoners and detainees

- American Vietnam War flying aces

- American people convicted of tax crimes

- Aviators from California

- California Republicans

- Cancer survivors

- Living people

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from California

- National University alumni

- People from Los Angeles, California

- People from San Diego, California

- People from Shelby County, Missouri

- Political scandals in the United States by state

- Politicians convicted of mail and wire fraud

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government

- Recipients of the Navy Cross

- Recipients of the Purple Heart medal

- Recipients of the Silver Star

- Recipients of the Air Medal

- United States Naval Aviators

- United States Navy officers

- University of Missouri alumni