Astrology and science

| Astrology |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Traditions |

| Branches |

| Astrological signs |

| Symbols |

Astrology consists of a number of belief systems which hold that there is a relationship between astronomical phenomena and events in the human world. Astrology has been rejected by the scientific community as having no explanatory power for describing the universe. Scientific testing of astrology has been conducted, and no evidence has been found to support the premises or purported effects outlined in astrological traditions.[1]: 424

Where astrology has made falsifiable predictions, it has been falsified.[1]: 424 The most famous test was headed by Shawn Carlson and included a committee of scientists and a committee of astrologers. It led to the conclusion that Natal astrology performed no better than chance. Astrologer and psychologist Michel Gauquelin, claimed to have found statistical support for "the Mars effect" in the birth dates of athletes, but it could not be replicated in further studies. The organisers of later studies claimed that Gauquelin had tried to influence their inclusion criteria for the study, by suggesting specific individuals be removed. It has also been suggested, by Geoffrey Dean, that the reporting of birth times by parents (before the 1950s) may have caused the apparent effect.

There is no proposed mechanism of action by which the positions and motions of stars and planets could affect people and events on Earth that does not contradict well understood, basic aspects of biology and physics.[2]: 249 [3]

Introduction

The majority of professional astrologers rely on performing astrology-based personality tests and making relevant predictions about the remunerator's future.[4]: 83 Those who continue to have faith in astrology have been characterised as doing so "in spite of the fact that there is no verified scientific basis for their beliefs, and indeed that there is strong evidence to the contrary".[5] Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson commented on astrological belief, saying that "part of knowing how to think is knowing how the laws of nature shape the world around us. Without that knowledge, without that capacity to think, you can easily become a victim of people who seek to take advantage of you".[6]

Astrologers often avoid making verifiable predictions and instead rely on making vague statements which allows them to try to avoid falsification.[7]: 48–49 Across several centuries of testing, the predictions of astrology have never been more accurate than that expected by chance alone.[4] One approach used in testing astrology quantitatively is through blind experiment. When specific predictions from astrologers were tested in rigorous experimental procedures in the Carlson test, the predictions were falsified.[1]

Carlson's experiment

The Shawn Carlson's double-blind chart matching tests, in which 28 astrologers agreed to match over 100 natal charts to psychological profiles generated by the California Psychological Inventory (CPI) test, is one of the most renowned tests of astrology.[8][9] The experimental protocol used in Carlson's study was agreed to by a group of physicists and astrologers prior to the experiment.[1] Astrologers, nominated by the National Council for Geocosmic Research, acted as the astrological advisors, and helped to ensure, and agreed, that the test was fair.[9]: 117 [10]: 420 They also chose 26 of the 28 astrologers for the tests, the other 2 being interested astrologers who volunteered afterwards.[10]: 420 The astrologers came from Europe and the United States.[9]: 117 The astrologers helped to draw up the central proposition of natal astrology to be tested.[10]: 419 Published in Nature in 1985, the study found that predictions based on natal astrology were no better than chance, and that the testing "clearly refutes the astrological hypothesis".[10]

Dean and Kelly

The scientist and former astrologer, Geoffrey Dean and psychologist Ivan Kelly,[11] conducted a large scale scientific test, involving more than one hundred cognitive, behavioural, physical and other variables, but found no support for astrology.[12] Furthermore, a meta-analysis was conducted pooling 40 studies consisting of 700 astrologers and over 1,000 birth charts. Ten of the tests, which had a total of 300 participating, involved the astrologers picking the correct chart interpretation out of a number of others which were not the astrologically correct chart interpretation (usually 3 to 5 others). When the date and other obvious clues were removed no significant results were found to suggest there was any preferred chart.[12]: 190 A further test involved 45 confident[a] astrologers, with an average of 10 years experience and 160 test subjects (out of an original sample size of 1198 test subjects) who strongly favoured certain characteristics in the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire to extremes.[12]: 191 The astrologers performed much worse than merely basing decisions off the individuals age, and much worse than 45 control subjects who did not use birth charts at all.[b][12]: 191

Mars effect

In 1955, astrologer[14] and psychologist Michel Gauquelin stated that although he had failed to find evidence to support such indicators as the zodiacal signs and planetary aspects in astrology, he had found positive correlations between the diurnal positions of some of the planets and success in professions (such as doctors, scientists, athletes, actors, writers, painters, etc.) which astrology traditionally associates with those planets.[13] The best-known of Gauquelin's findings is based on the positions of Mars in the natal charts of successful athletes and became known as the "Mars effect".[15]: 213 A study conducted by seven French scientists attempted to replicate the claim, but found no statistical evidence.[15]: 213–214 They attributed the effect to selective bias on Gauquelin's part, accusing him of attempting to persuade them to add or delete names from their study.[16]

Geoffrey Dean has suggested that the effect may be caused by self-reporting of birth dates by parents rather than any issue with the study by Gauquelin. The suggestion is that a small subset of the parents may have had changed birth times to be consistent with better astrological charts for a related profession. The sample group was taken from a time where belief in astrology was more common. Gauquelin had failed to find the Mars effect in more recent populations, where a nurse or doctor recorded the birth information. The number of births under astrologically undesirable conditions was also lower, indicating more evidence that parents choose dates and times to suit their beliefs.[9]: 116

Historical relationship with astronomy

Ptolemy's work on astronomy was driven to some extent by the desire, like all astrologers of the time, to easily calculate the planetary movements.[17]: 40 Early western astrology operated under the ancient Greek concepts of the Macrocosm and microcosm; and thus medical astrology related what happened to the planets and other objects in the sky to medical operations. This provided a further motivator for the study of astronomy. [17]: 73 While still defending the practice of astrology, Ptolemy acknowledged that the predictive power of astronomy for the motion of the planets and other celestial bodies ranked above astrological predictions.[18]: 344

During the Islamic Golden Age, astronomy was funded so that the astronomical parameters, such as the eccentricity of the sun's orbit, required for the Ptolemaic model could be calculated to a sufficient accuracy and precision. Those in positions of power, like the Fatimid Caliphate vizier in 1120, funded the construction of observatories so that astrological predictions, fuelled by precise planetary information, could be made.[17]: 55–56 Since the observatories were built to help in making astrological predictions, few of these observatories lasted long due to the prohibition against astrology within Islam, and most were torn down during or just after construction.[17]: 57

The clear rejection of astrology in works of astronomy started in 1679, with the yearly publication La Connoissance des temps.[17]: 220 Unlike the west, in Iran, the rejection of heliocentrism continued up towards the start of the 20th century, in part motivated by a fear that this would undermine the widespread belief in astrology and Islamic cosmology in Iran.[19]: 10 The first work, Falak al-sa'ada by Ictizad al-Saltana, aimed at undermining this belief in astrology and "old astronomy" in Iran was published in 1861. On astrology, it cited the inability of different astrologers to make the same prediction about what occurs following a conjunction, and described the attributes astrologers gave to the planets to be implausible.[19]: 17–18

Philosophy of science

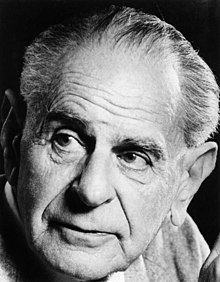

Science and non-science are often distinguished by the criterion of falsifiability. The criterion was first proposed by philosopher of science Karl Popper. To Popper, science does not rely on induction, instead scientific investigations are inherently attempts to falsify existing theories through novel tests. If a single test fails, then the theory is falsified. Therefore, any test of a scientific theory must prohibit certain results which will falsify the theory, and expect other specific results which will be consistent with the theory. Using this criterion of falsifiability, astrology is a pseudoscience.[20] Astrology was Popper's most frequent example of pseudoscience.[21]: 7 Popper regarded astrology as "pseudo-empirical" in that "it appeals to observation and experiment", but "nevertheless does not come up to scientific standards".[7]: 44 In contrast to scientific disciplines, astrology has not responded to falsification through experiment. According to Professor of neurology Terence Hines this is a hallmark of pseudoscience. [22]: 206 Astrology has not demonstrated its effectiveness in controlled studies and has no scientific validity,[1][4]: 85 and as such, is regarded as pseudoscience[23][24]: 1350 .

In contrast to Popper, the philosopher Thomas Kuhn argued that it was not lack of falsifiability that makes astrology unscientific, but rather that the process and concepts of astrology are non-empirical.[25]: 401 To Kuhn, although astrologers had, historically, made predictions that "categorically failed", this in itself does not make it unscientific, nor do the attempts by astrologers to explain away the failure by claiming it was due to the creation of a horoscope being very difficult. Rather, in Kuhn's eyes, astrology is not science because it was always more akin to medieval medicine; they followed a sequence of rules and guidelines for a seemingly necessary field with known shortcomings, but they did no research because the fields are not amenable to research[21]: 8 , and so "they had no puzzles to solve and therefore no science to practise". [25]: 401 [21]: 8 While an astronomer could correct for failure, an astrologer could not. An astrologer could only explain away failure but could not revise the astrological hypothesis in a meaningful way. As such, to Kuhn, even if the stars could influence the path of humans through life astrology is not scientific. [21]: 8

Philosopher Paul Thagard believed that Astrology can not be regarded as falsified in this sense until it has been replaced with a successor. In the case of predicting behaviour, psychology is the alternative.[26]: 228 To Thagard a further criteria of demarcation of science from pseudoscience was that the state of the art must progress and that the community of researchers should be attempting to compare the current theory to alternatives, and not be "selective in considering confirmations and disconfirmations".[26]: 227–228 Progress is defined here as explaining new phenomena and solving existing problems, yet astrology has failed to progress having only changed little in nearly 2000 years.[26]: 228 To Thagard, astrologers are acting as though engaged in Normal science believing that the foundations of astrology were well established despite the "many unsolved problems", and in the face of better alternative theories (Psychology). For these reasons Thagard viewed astrology as pseudoscience. [26]: 228

To Thagard, astrology should not be regarded as a pseudoscience on the failure of Gauquelin's to find any correlation between the various astrological signs and someone's career, twins not showing the expected correlations from having the same signs in twin studies, lack of agreement on the significance of the planets discovered since Ptolemy's time and large scale disasters wiping out individuals with vastly different signs at the same time, astrology.[26]: 226–227 Rather, his demarcation of science requires three distinct foci; "theory, community [and] historical context". While verification and falsifiability had focussed on the theory, Kuhn's work had focussed on the historical context, but the astrological community should also be considered. Whether or not they:[26]: 226–227

- are focussed on comparing their approach to others.

- have a consistent approach.

- try to falsify their theory through experiment.

In this approach, true falsification rather than modifying a theory to avoid the falsification only really occurs when an alternative theory is proposed.[26]: 228

Perspectives from psychology

It has also been shown that confirmation bias is a psychological factor that contributes to belief in astrology.[27]: 344 [28]: 180–181 [29]: 42–48 Confirmation bias is a form of cognitive bias.[c][30]: 553 From the literature, Astrology believers often tend to selectively remember those predictions which have turned out to be true, and do not remember those predictions which happen to be false. Another, separate, form of confirmation bias also plays a role, where believers often fail to distinguish between messages that demonstrate special ability and those which do not.[28]: 180–181 Thus there are two distinct forms of confirmation bias that are under study with respect to astrological belief.[28]: 180–181

The Barnum effect is where people accept unclear expositions of their personality if there is the appearance of some complex process in the derivation of the personality profile. If more information is requested for a prediction, the more accepting people are of the results.[27]: 344 In 1949 Bertram Forer conducted a personality test on students in his classroom.[27]: 344 While seemingly giving the students individualised results, he instead gave each student an identical sheet that discussed their personality. The personality descriptions were taken from a book on Astrology. When the students were asked to comment on the accuracy of the test, more than 40% gave it the top mark of 5 out of 5, and the average rating was 4.2.[31]: 134, 135 The results of this study have been replicated in numerous other studies.[32]: 382 The study of this Barnum/Forer effect has been mostly focused on the level of acceptance of fake horoscopes and fake astrological personality profiles.[32]: 382 Recipients of these personality assessments consistently fail to distinguish common and uncommon personality descriptors.[32]: 383 In a study by Paul Rogers and Janice Soule (2009), which was consistent with previous research on the issue, it was found that those who believed in astrology are generally more susceptible to giving more credence to the Barnum profile than sceptics.[32]: 393

By a process known as self-attribution, it has been shown in numerous studies that individuals with knowledge of astrology tend to describe their personality in terms of traits compatible with their sun sign. The effect is heightened when the individuals were aware the personality description was being used to discuss astrology. Individuals who were not familiar with astrology had no such tendency.[33]

Sociological viewpoints

In 1953, sociologist Theodor W. Adorno conducted a study of the astrology column of a Los Angeles newspaper as part of a project examining mass culture in capitalist society.[34]: 326 Adorno believed that popular astrology, as a device, invariably led to statements which encouraged conformity, and that astrologers who went against conformity with statement discouraging performance at work etc. would risk losing their jobs.[34]: 327 Adorno concluded that astrology was a large-scale manifestation of systematic irrationalism, where individuals were subtly being led to believe that the author of the column was addressing them directly through the use of flattery and vague generalisations.[35] Adorno drew a parallel with the phrase opium of the people, by Karl Marx, by commenting "occultism is the metaphysic of the dopes". [34]: 329

Lack of consistency

Testing the validity of astrology can be difficult because there is no consensus amongst astrologers as to what astrology is or what it can predict.[4]: 83 Most professional astrologers are paid to predict the future or describe a person's personality and life, but most horoscopes only make vague untestable statements that can apply to almost anyone.[4]: 83

Georges Charpak and Henri Broch dealt with claims from astrology in the book Debunked! ESP, Telekinesis, and other Pseudoscience.[36] They pointed out that astrologers have only a small knowledge of astronomy and that they often do not take into account basic features such as the precession of the equinoxes which would change the position of the sun with time; they commented on the example of Elizabeth Teissier who claimed that "the sun ends up in the same place in the sky on the same date each year" as the basis for claims that two people with the same birthday but a number of years apart should be under the same planetary influence. Charpak and Broch noted that "there is a difference of about twenty-two thousand miles between Earth's location on any specific date in two successive years" and that thus they should not be under the same influence according to astrology. Over a 40 years period there would be a difference greater than 780,000 miles.[37]: 6–7

The tropical zodiac has no connection to the stars and as long as no claims are made that the constellations themselves are in the associated sign it avoids the issue of precession seemingly moving the constellations.[37] Charpak and Broch, noting this, referred to astrology based on the tropical zodiac as being "empty boxes that have nothing to do with anything and are devoid of any consistency or correspondence with the stars".[37] Sole usage of the tropical zodiac is inconsistent with references made, by the same astrologers, to the Age of Aquarius which is dependent on when the vernal point enters the constellation of Aquarius.[1]

Some astrologers make claims that the position of all the planets must be taken into account, but astrologers were unable to predict the existence of Neptune based on mistakes in horoscopes. Instead Neptune was predicted using Newton's law of universal gravitation.[4] The grafting on of Uranus, Neptune and Pluto into the astrology discourse was done on an ad-hoc basis.[1]

On the demotion of Pluto to the status of dwarf planet, Philip Zarka of the Paris Observatory in Meudon, France wondered how astrologers should respond:[1]

Should astrologers remove it from the list of luminars [Sun, Moon and the 8 planets other than earth] and confess that it did not actually bring any improvement? If they decide to keep it, what about the growing list of other recently discovered similar bodies (Sedna, Quaoar. etc), some of which even have satellites (Xena, 2003EL61)?

Lack of mechanism

Astrology has been criticised for failing to provide a physical mechanism that links the movements of celestial bodies to their purported effects on human behaviour. In a lecture in 2001, Stephen Hawking stated "The reason most scientists don't believe in astrology is because it is not consistent with our theories that have been tested by experiment."[38] In 1975, amid increasing popular interest in astrology, The Humanist magazine presented a rebuttal of astrology in a statement put together by Bart J. Bok, Lawrence E. Jerome, and Paul Kurtz.[5] The statement, entitled 'Objections to Astrology', was signed by 186 astronomers, physicists and leading scientists of the day. They said that there is no scientific foundation for the tenets of astrology and warned the public against accepting astrological advice without question. Their criticism focused on the fact that there was no mechanism whereby astrological effects might occur:

We can see how infinitesimally small are the gravitational and other effects produced by the distant planets and the far more distant stars. It is simply a mistake to imagine that the forces exerted by stars and planets at the moment of birth can in any way shape our futures.[5]

Astronomer Carl Sagan declined to sign the statement. Sagan said he took this stance not because he thought astrology had any validity, but because he thought that the tone of the statement was authoritarian, and that dismissing astrology because there was no mechanism (while "certainly a relevant point") was not in itself convincing. In a letter published in a follow-up edition of The Humanist, Sagan confirmed that he would have been willing to sign such a statement had it described and refuted the principal tenets of astrological belief. This, he argued, would have been more persuasive and would have produced less controversy.[5]

Many astrologers claim that astrology is scientific.[39] Some of these astrologers have proposed conventional causal agents such as electromagnetism and gravity.[39][40] Scientists reject these mechanisms as implausible[39] since, for example, the magnetic field, when measured from earth, of a large but distant planet such as Jupiter is far smaller than that produced by ordinary household appliances.[40] Carl Jung sought to invoke synchronicity, the claim that two events have some sort of acausaul connection, to explain the lack of statistically significant results on astrology from a single study he conducted. However, synchronicity itself is considered to be neither testable nor falsifiable.[41] The study was subsequently heavily criticised for its non-random sample and its use of statistics and also its lack of consistency with astrology.[d][42]

Notes

- ^ The level of confidence was self rated by the astrologers themselves.

- ^ Also discussed in Martens, Ronny (1998). Making sense of astrology. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-218-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ see Heuristics in judgement and decision making

- ^ Jung made the claims, despite being aware that there was no statistical significance in the results. Looking for coincidences post hoc is of very dubious value, see Data dredging.[41]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zarka, Philippe (2011). "Astronomy and astrology". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 5 (S260): 420–425. doi:10.1017/S1743921311002602.

- ^ Vishveshwara, edited by S.K. Biswas, D.C.V. Mallik, C.V. (1989). Cosmic perspectives : essays dedicated to the memory of M.K.V. Bappu (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34354-2.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, vol. 1. Dordrecht u.a.: Reidel u.a. 1978. ISBN 978-0-917586-05-7.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help);|first=missing|last=(help)- "Chapter 7: Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". science and engineering indicators 2006. National Science Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

About three-fourths of Americans hold at least one pseudoscientific belief; i.e., they believed in at least 1 of the 10 survey items[29]" ..." Those 10 items were extrasensory perception (ESP), that houses can be haunted, ghosts/that spirits of dead people can come back in certain places/situations, telepathy/communication between minds without using traditional senses, clairvoyance/the power of the mind to know the past and predict the future, astrology/that the position of the stars and planets can affect people's lives, that people can communicate mentally with someone who has died, witches, reincarnation/the rebirth of the soul in a new body after death, and channeling/allowing a "spirit-being" to temporarily assume control of a body.

- "Chapter 7: Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". science and engineering indicators 2006. National Science Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f The cosmic perspective (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pearson/Addison-Wesley. 2007. pp. 82–84. ISBN 0-8053-9283-1.

{{cite book}}:|first=missing|last=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Objections to Astrology: A Statement by 186 Leading Scientists". The Humanist, September/October 1975. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009.

- The Humanist, volume 36, no.5 (1976).

- Bok, Bart J. (1982). "Objections to Astrology: A Statement by 186 Leading Scientists". In Patrick Grim (ed.). Philosophy of Science and the Occult. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 14–18. ISBN 0-87395-572-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- ^ "Ariz. Astrology School Accredited". The Washington Post. 27 August 2001.

- ^ a b Popper, Karl (2004). Conjectures and refutations : the growth of scientific knowledge (Reprinted. ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28594-1.

- The relevant piece is also published in, Schick Jr, Theodore, (2000). Readings in the philosophy of science : from positivism to postmodernism. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Pub. pp. 33–39. ISBN 0-7674-0277-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- The relevant piece is also published in, Schick Jr, Theodore, (2000). Readings in the philosophy of science : from positivism to postmodernism. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Pub. pp. 33–39. ISBN 0-7674-0277-4.

- ^ Muller, Richard (2010). "Web site of Richard A. Muller, Professor in the Department of Physics at the University of California at Berkeley,". Retrieved 2011-08-02.My former student Shawn Carlson published in Nature magazine the definitive scientific test of Astrology.

Maddox, Sir John (1995). "John Maddox, editor of the science journal Nature, commenting on Carlson's test". Retrieved 2011-08-02. "... a perfectly convincing and lasting demonstration." - ^ a b c d Smith, Jonathan C. (2010). Pseudoscience and extraordinary claims of the paranormal : a critical thinker's toolkit. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8123-5.

- ^ a b c d Carlson, Shawn (1985). "A double-blind test of astrology" (PDF). Nature. 318 (6045): 419–425. Bibcode:1985Natur.318..419C. doi:10.1038/318419a0.

- ^ Matthews, Robert (17 Aug 2003). "Astrologers fail to predict proof they are wrong". The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d Dean G., Kelly, I. W. (2003). "Is Astrology Relevant to Consciousness and Psi?". Journal of Consciousness Studies. 10 (6–7): 175–198.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gauquelin, Michel (1955). L'influence des astres : étude critique et expérimentale. Paris: Éditions du Dauphin.

- ^ Pont, Graham (2004). "Philosophy and Science of Music in Ancient Greece". Nexus Network Journal. 6 (1): 17–29. doi:10.1007/s00004-004-0003-x.

- ^ a b Carroll, Robert Todd (2003). The skeptic's dictionary : a collection of strange beliefs, amusing deceptions, and dangerous delusions. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-27242-6.

- ^ Nienhuys, Claude Benski et al. with a commentary by Jan Willem (1995). The "Mars effect : a French test of over 1,000 sports champions. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-87975-988-7.

- ^ a b c d e Hoskin, edited by Michael (2003). The Cambridge concise history of astronomy (Printing 2003. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521572916.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Evans, James (1998). The history & practice of ancient astronomy. New York: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 9780195095395.

- ^ a b Arjomand, Kamran (1997). "The Emergence of Scientific Modernity in Iran: Controversies Surrounding Astrology and Modern Astronomy in the Mid-Nineteenth Century". Iranian Studies. Taylor and Francis, for the International Society for Iranian Studies.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Stephen Thornton, Edward N. Zalta (older edition). "Karl Popper". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b c d Kuhn, Thomas (1970). Imre Lakatos & Alan Musgrave (ed.). Proceedings of the International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science [held at Bedford college, Regent's Park, London, from July 11th to 17th 1965] (Reprint. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0521096235.

- ^ Cogan, Robert (1998). Critical thinking : step by step. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America. ISBN 0761810676.

- ^ "Science and Pseudo-Science". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)- "Astronomical Pseudo-Science: A Skeptic's Resource List". Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

- ^ Hartmann, P (2006). "The relationship between date of birth and individual differences in personality and general intelligence: A large-scale study". Personality and Individual Differences. 40 (7): 1349–1362. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.017.

To optimise the chances of finding even remote relationships between date of birth and individual differences in personality and intelligence we further applied two different strategies. The first one was based on the common chronological concept of time (e.g. month of birth and season of birth). The second strategy was based on the (pseudo-scientific) concept of astrology (e.g. Sun Signs, The Elements, and astrological gender), as discussed in the book Astrology: Science or superstition? by Eysenck and Nias (1982).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Wright, Peter (1975). "Astrology and Science in Seventeenth-Century England". Social Studies of Science: 399–422.

- ^ a b c d e f g Thagard, Paul R. (1978). "Why Astrology is a Pseudoscience". Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association. 1. The University of Chicago Press: 223-234.

- ^ a b c Allum, Nick (13 December 2010). "What Makes Some People Think Astrology Is Scientific?". Science Communication. 33 (3): 341–366. doi:10.1177/1075547010389819.

This underlies the "Barnum effect". Named after the 19th-century showman Phineas T. Barnum, whose circus act provided "a little something for everyone", it refers to the idea that people will believe a statement about their personality that is vague or trivial if they think that it derives from some systematic procedure tailored especially for them (Dickson & Kelly, 1985; Furnham & Schofield, 1987; Rogers & Soule, 2009; Wyman & Vyse, 2008). For example, the more birth detail is used in an astrological prediction or horoscope, the more credulous people tend to be (Furnham, 1991). However, confirmation bias means that people do not tend to pay attention to other information that might disconfirm the credibility of the predictions.

- ^ a b c Nickerson, Raymond S. Nickerson (1998). "Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises". Review of General Psychology. 2. 2 (2): 175–220. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175.

- ^ Eysenck, H.J. (1984). Astrology : science or superstition?. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-022397-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gonzalez, edited by Jean-Paul Caverni, Jean-Marc Fabre, Michel (1990). Cognitive biases. Amsterdam: North-Holland. ISBN 0-444-88413-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paul, Annie Murphy (2005). The cult of personality testing : how personality tests are leading us to miseducate our children, mismanage our companies, and misunderstand ourselves (1st pbk. ed.). New York, N.Y.: Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-8072-5.

- ^ a b c d Rogers, P. (5 March 2009). "Cross-Cultural Differences in the Acceptance of Barnum Profiles Supposedly Derived From Western Versus Chinese Astrology". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 40 (3): 381–399. doi:10.1177/0022022109332843.

The Barnum effect is a robust phenomenon, having been demonstrated in clinical, occupational, educational, forensic, and military settings as well as numerous ostensibly paranormal contexts (Dickson & Kelly, 1985; Furnham & Schofield, 1987; Snyder, Shenkel & Lowery, 1977; Thiriart, 1991). In the first Barnum study, Forer (1949) administered" "Third, astrological believers deemed a Barnum profile supposedly derived from astrology to be a better description of their own personality than did astrological skeptics. This was true regardless of respondent's ethnicity and/or apparent profile source. This reinforces still further the view that individuals who endorse astrological beliefs are prone to judging the legitimacy and usefulness of horoscopes according to their a priori expectations

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wunder, Edgar (1 December 2003). "Self-attribution, sun-sign traits, and the alleged role of favourableness as a moderator variable: long-term effect or artefact?". Personality and Individual Differences. 35 (8): 1783–1789. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00002-3.

The effect was replicated several times (Eysenck & Nias 1981,1982; Fichten & Sunerton, 1983; Jackson, 1979; Kelly, 1982; Smithers & Cooper, 1978), even if no reference to astrology was made until the debriefing of the subjects (Hamilton, 1995; Van Rooij, 1994, 1999), or if the data were gathered originally for a purpose which has nothing to do with astrology at all (Clarke, Gabriels, & Barnes, 1996; Van Rooij, Brak, & Commandeur, 1988), but the effect is stronger when a cue is given to the subjects that the study is about astrology (Van Rooij 1994). Early evidence for sun-sign derived self-attribution effects has already been reported by Silverman (1971) and Delaney & Woodyard (1974). In studies with subjects unfamiliar with the meaning of the astrological sun-sign symbolism, no effect was observed (Fourie, 1984; Jackson & Fiebert, 1980; Kanekar & Mukherjee, 1972; Mohan, Bhandari, & Meena, 1982; Mohan and Gulati, 1986; Saklofske, Kelly, & McKerracher, 1982; Silverman & Whitmer, 1974; Veno & Pamment, 1979).

- ^ a b c Cary J. Nederman and James Wray Goulding (Winter, 1981). "Popular Occultism and Critical Social Theory: Exploring Some Themes in Adorno's Critique of Astrology and the Occult". Sociological Analysis. 42.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Theodor W. Adorno (1974). "The Stars Down to Earth: The Los Angeles Times Astrology Column". Telos. 1974 (19): 13–90. doi:10.3817/0374019013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Giomataris, Ioannis. "Nature Obituary Georges Charpak (1924–2010)". Nature. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ a b c Charpak, Georges (2004). Debunked! : ESP, telekinesis, and other pseudoscience. Baltimore u.a.9: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. pp. 6, 7. ISBN 0-8018-7867-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "British Physicist Debunks Astrology in Indian Lecture". Associated Press.

- ^ a b c Chris, French. "Astrologers and other inhabitants of parallel universes". 7 February 2012. The Guardian. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ a b Randi, James. "UK MEDIA NONSENSE — AGAIN". 21 May 2004. Swift, Online newspaper of the JREF. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 22 July 2011 suggested (help) - ^ a b editor, Michael Shermer, (2002). The Skeptic encyclopedia of pseudoscience. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 241. ISBN 1-57607-653-9.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Samuels, Andrew (1990). Jung and the post-Jungians. London: Tavistock/Routledge. p. 80. ISBN 0-203-35929-1.

External links

- Astrology & Science: The Scientific Exploration of Astrology

- Merrifield, Michael. "Right Ascension & Declination". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham. – which also discusses ascension and declination errors in different systems of astrology