Desalination

| Water desalination

|

|---|

| Methods |

|

Desalination, desalinization, and desalinisation refer to any of several processes that remove some amount of salt and other minerals from saline water. More generally, desalination may also refer to the removal of salts and minerals,[1] as in soil desalination.[2]

Salt water is desalinated to produce fresh water suitable for human consumption or irrigation. One potential byproduct of desalination is salt. Desalination is used on many seagoing ships and submarines. Most of the modern interest in desalination is focused on developing cost-effective ways of providing fresh water for human use. Along with recycled wastewater, this is one of the few rainfall-independent water sources.[3]

Costs of desalinating sea water (infrastructure, energy and maintenance) are generally higher than the alternatives (fresh water from rivers or groundwater, water recycling and water conservation), but alternatives are not always applicable. Achievable costs in 2013 range from 0.5 to 1 US$/cubic metre (2 to 4 US$/kgal). (See below: "Economics"). The cost of untreated fresh water in the developing world can reach 5 US$/cubic metre [4]

Average Water Consumption & Cost of Supply by Sea Water Desalination (+/-50%)...

| Area | Consumption USgal/person/day | Consumption litre/person/day | Desalinated Water Cost US$/person/day |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 100 | 380 | 0.29 |

| Europe | 50 | 190 | 0.14 |

| Africa | 15 | 60 | 0.05 |

| UN recommended minimum | 13 | 50 | 0.04 |

Energy consumption of sea water desalination can be as low as 3 kWh/m^3,[5] similar to the energy consumption of existing fresh water supplies transported over large distances,[6] but much higher than local fresh water supplies which use 0.2 kWh/m^3 or less.[7]

The laws of physics determine a minimum energy consumption for sea water desalination around 1 kWh/m^3,[8] excluding pre-filtering and intake/outfall pumping. Under 2 kWh/m^3 [9] has been achieved with existing reverse osmosis membrane technology, leaving limited scope for further energy reductions.

Supplying all domestic water by sea water desalination would increase US Domestic energy consumption by around 10%, about the amount of energy used by a domestic refrigerator [10]

Energy Consumption of Sea Water Desalination Methods...[11]

| Desalination Method >> | Multi-stage Flash MSF | Multi-Effect Distillation MED | Mechanical Vapor Compression MVC | Reverse Osmosis RO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical energy kWh/m^3 | 4-6 | 1.5-2.5 | 7-12 | 3-5.5 |

| Thermal energy kWh/m^3 | 50-110 | 60-110 | None | None |

| Electrical equivalent of thermal energy kWh/m^3 | 9.5-19.5 | 5-8.5 | None | None |

| Total equivalent electrical energy kWh/m^3 | 13.5-25.5 | 6.5-11 | 7-12 | 3-5.5 |

Note: "Electrical equivalent" of thermal energy is that electrical energy which cannot be produced in a turbine because of extraction of the heating steam

Desalination is particularly relevant to countries such as Australia, which traditionally have relied on collecting rainfall behind dams to provide their drinking water supplies. According to the International Desalination Association, in 2009, 14,451 desalination plants operated worldwide, producing 59.9 million cubic meters per day, a year-on-year increase of 12.3%.[12] The production was 68 million m3 in 2010, and expected to reach 120 million m3 by 2020; some 40 million m3 is planned for the Middle East.[13] The world's largest desalination plant is the Jebel Ali Desalination Plant (Phase 2) in the United Arab Emirates.[14]

A – steam in

B – seawater in

C – potable water out

D – waste out

E – steam out

F – heat exchange

G – condensation collection

H – brine heater

Methods

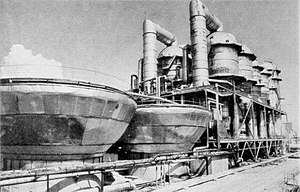

The traditional process used in these operations is vacuum distillation—essentially the boiling of water at less than atmospheric pressure and thus a much lower temperature than normal. This is because the boiling of a liquid occurs when the vapor pressure equals the ambient pressure and vapor pressure increases with temperature. Thus, because of the reduced temperature, low-temperature "waste" heat from electrical power generation or industrial processes can be used.

The principal competing processes use membranes to desalinate, principally applying reverse osmosis technology.[15] Membrane processes use semipermeable membranes and pressure to separate salts from water. Reverse osmosis plant membrane systems typically use less energy than thermal distillation, which has led to a reduction in overall desalination costs over the past decade. Desalination remains energy intensive, however, and future costs will continue to depend on the price of both energy and desalination technology.

Considerations and criticism

Cogeneration

Cogeneration is the process of using excess heat from electricity generation for another task: in this case the production of potable water from seawater or brackish groundwater in an integrated, or "dual-purpose", facility where a power plant provides the energy for desalination. Alternatively, the facility's energy production may be dedicated to the production of potable water (a stand-alone facility), or excess energy may be produced and incorporated into the energy grid (a true cogeneration facility). Cogeneration takes various forms, and theoretically any form of energy production could be used. However, the majority of current and planned cogeneration desalination plants use either fossil fuels or nuclear power as their source of energy. Most plants are located in the Middle East or North Africa, which use their petroleum resources to offset limited water resources. The advantage of dual-purpose facilities is they can be more efficient in energy consumption, thus making desalination a more viable option for drinking water.[16][17]

In a December 26, 2007, opinion column in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Nolan Hertel, a professor of nuclear and radiological engineering at Georgia Tech, wrote, "... nuclear reactors can be used ... to produce large amounts of potable water. The process is already in use in a number of places around the world, from India to Japan and Russia. Eight nuclear reactors coupled to desalination plants are operating in Japan alone, nuclear desalination plants could be a source of large amounts of potable water transported by pipelines hundreds of miles inland..."[18]

Additionally, the current trend in dual-purpose facilities is hybrid configurations, in which the permeate from a reverse osmosis desalination component is mixed with distillate from thermal desalination. Basically, two or more desalination processes are combined along with power production. Such facilities have already been implemented in Saudi Arabia at Jeddah and Yanbu.[19]

A typical aircraft carrier in the US military uses nuclear power to desalinate 400,000 US gallons (1,500,000 L; 330,000 imp gal) of water per day.[20]

Economics

Factors that determine the costs for desalination include capacity and type of facility, location, feed water, labor, energy, financing, and concentrate disposal. Desalination stills now control pressure, temperature and brine concentrations to optimize efficiency. Nuclear-powered desalination might be economical on a large scale.[21][22]

While noting costs are falling, and generally positive about the technology for affluent areas in proximity to oceans, a 2004 study argued, "Desalinated water may be a solution for some water-stress regions, but not for places that are poor, deep in the interior of a continent, or at high elevation. Unfortunately, that includes some of the places with biggest water problems.", and, "Indeed, one needs to lift the water by 2,000 metres (6,600 ft), or transport it over more than 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) to get transport costs equal to the desalination costs. Thus, it may be more economical to transport fresh water from somewhere else than to desalinate it. In places far from the sea, like New Delhi, or in high places, like Mexico City, high transport costs would add to the high desalination costs. Desalinated water is also expensive in places that are both somewhat far from the sea and somewhat high, such as Riyadh and Harare. In many places, the dominant cost is desalination, not transport; the process would therefore be relatively less expensive in places like Beijing, Bangkok, Zaragoza, Phoenix, and, of course, coastal cities like Tripoli."[23] After being desalinated at Jubail, Saudi Arabia, water is pumped 200 miles (320 km) inland through a pipeline to the capital city of Riyadh.[24] For coastal cities, desalination is increasingly viewed as an untapped and unlimited water source.

In Israel as of 2005, desalinating water costs US$ 0.53 per cubic meter (0.053¢ per liter).[25] As of 2006, Singapore was desalinating water for US$ 0.49 per cubic meter.[26] The city of Perth began operating a reverse osmosis seawater desalination plant in 2006, and the Western Australian government announced a second plant will be built to serve the city's needs.[27] A desalination plant is now operating in Australia's largest city, Sydney,[28] and the Wonthaggi desalination plant was under construction in Wonthaggi, Victoria.

The Perth desalination plant is powered partially by renewable energy from the Emu Downs Wind Farm.[29] A wind farm at Bungendore in New South Wales was purpose-built to generate enough renewable energy to offset the Sydney plant's energy use,[30] mitigating concerns about harmful greenhouse gas emissions, a common argument used against seawater desalination.

In December 2007, the South Australian government announced it would build a seawater desalination plant for the city of Adelaide, Australia, located at Port Stanvac. The desalination plant was to be funded by raising water rates to achieve full cost recovery.[31][32] An online, unscientific poll showed nearly 60% of votes cast were in favor of raising water rates to pay for desalination.[33]

A January 17, 2008, article in the Wall Street Journal stated, "In November, Connecticut-based Poseidon Resources Corp. won a key regulatory approval to build the $300 million water-desalination plant in Carlsbad, north of San Diego. The facility would produce 50,000,000 US gallons (190,000,000 L; 42,000,000 imp gal) of drinking water per day, enough to supply about 100,000 homes ... Improved technology has cut the cost of desalination in half in the past decade, making it more competitive ... Poseidon plans to sell the water for about $950 per acre-foot [1,200 cubic meters (42,000 cu ft)]. That compares with an average [of] $700 an acre-foot [1200 m³] that local agencies now pay for water." [34] In June 2012, new estimates were released that showed the cost to the water authority had risen to $2,329 per acre-foot. [35] Each $1,000 per acre-foot works out to $3.06 for 1,000 gallons, or $.81 per cubic meter.[36]

While this regulatory hurdle was met, Poseidon Resources is not able to break ground until the final approval of a mitigation project for the damage done to marine life through the intake pipe is received, as required by California law. Poseidon Resources has made progress in Carlsbad, despite an unsuccessful attempt to complete construction of Tampa Bay Desal, a desalination plant in Tampa Bay, FL, in 2001. The Board of Directors of Tampa Bay Water was forced to buy Tampa Bay Desal from Poseidon Resources in 2001 to prevent a third failure of the project. Tampa Bay Water faced five years of engineering problems and operation at 20% capacity to protect marine life, so stuck to reverse osmosis filters prior to fully using this facility in 2007.[37]

In 2008, a San Leandro, California company (Energy Recovery Inc.) was desalinating water for $0.46 per cubic meter.[38]

While desalinating 1,000 US gallons (3,800 L; 830 imp gal) of water can cost as much as $3, the same amount of bottled water costs $7,945.[39]

Environmental

Intake

In the United States, due to a 2011 court ruling under the Clean Water Act, ocean water intakes are no longer viable without reducing mortality of the life in the ocean, the plankton, fish eggs and fish larvae, by 90%.[40] The alternatives include beach wells to eliminate this concern, but require more energy and higher costs, while limiting output.[41]

The Kwinana Desalination Plant opened in Perth in 2007. Water there and at Queensland's Gold Coast Desalination Plant and Sydney's Kurnell Desalination Plant is withdrawn at only 0.1 meters per second (0.33 ft/s), which is slow enough to let fish escape. The plant provides nearly 140,000 cubic meters (4,900,000 cu ft) of clean water per day.[42]

Outflow

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

All desalination processes produce large quantities of a concentrate, which may be increased in temperature, and contain residues of pretreatment and cleaning chemicals, their reaction byproducts, and heavy metals due to corrosion. Chemical pretreatment and cleaning are a necessity in most desalination plants, which typically includes the treatment against biofouling, scaling, foaming and corrosion in thermal plants, and against biofouling, suspended solids and scale deposits in membrane plants.[43]

To limit the environmental impact of returning the brine to the ocean, it can be diluted with another stream of water entering the ocean, such as the outfall of a wastewater treatment or power plant. While seawater power plant cooling water outfalls are not as fresh as wastewater treatment plant outfalls, salinity is reduced. With medium to large power plant and desalination plant, the power plant's cooling water flow is likely to be at least several times larger than that of the desalination plant. Another method to reduce the increase in salinity is to mix the brine via a diffuser in a mixing zone. For example, once the pipeline containing the brine reaches the sea floor, it can split into many branches, each releasing brine gradually through small holes along its length. Mixing can be combined with power plant or wastewater plant dilution.

Brine is denser than seawater due to higher solute concentration. The ocean bottom is most at risk because the brine sinks and remains there long enough to damage the ecosystem. Careful reintroduction can minimize this problem. For example, for the desalination plant and ocean outlet structures to be built in Sydney from late 2007, the water authority stated the ocean outlets would be placed in locations at the seabed that will maximize the dispersal of the concentrated seawater, such that it will be indistinguishable beyond between 50 and 75 meters (164 and 246 ft) from the outlets. Typical oceanographic conditions off the coast allow for rapid dilution of the concentrated byproduct, thereby minimizing harm to the environment.

Alternatives without pollution

Some methods of desalination, particularly in combination with evaporation ponds and solar stills (solar desalination), do not discharge brine. They do not use chemicals in their processes nor the burning of fossil fuels. They do not work with membranes or other critical parts, such as components that include heavy metals, thus do not cause toxic waste (and high maintenance). A new approach that works like a solar still, but on the scale of industrial evaporation ponds is the Integrated Biotectural System. [44] It can be considered "full desalination" because it converts the entire amount of saltwater intake into distilled water. One of the unique advantages of this type of solar-powered desalination is the feasibility for inland operation. Standard advantages also include no air pollution from desalination power plants and no temperature increase of endangered natural water bodies from power plant cooling-water discharge. Another important advantage is the production of sea salt for industrial and other uses. Currently, 50% of the world's sea salt production still relies on fossil energy sources.

Alternatives to desalination

Increased water conservation and efficiency remain the most cost-effective priorities in areas of the world where there is a large potential to improve the efficiency of water use practices.[45] Wastewater reclamation for irrigation and industrial use provides multiple benefits over desalination.[46] Urban runoff and storm water capture also provide benefits in treating, restoring and recharging groundwater.[47]

A proposed alternative to desalination in the American Southwest is the commercial importation of bulk water from water-rich areas either by very large crude carriers converted to water carriers, or via pipelines. The idea is politically unpopular in Canada, where governments imposed trade barriers to bulk water exports as a result of a claim filed in 1999 under Chapter 11 of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) by Sun Belt Water Inc., a company established in 1990 in Santa Barbara, California, to address pressing local needs due to a severe drought in that area.[48]

Experimental techniques and other developments

Many desalination techniques have been researched, with varying degrees of success.

One such process was commercialized by Modern Water PLC using forward osmosis, with a number of plants reported to be in operation.[49][50][51]

The US government is working to develop practical solar desalination.[citation needed]

The Passarell process uses reduced atmospheric pressure rather than heat to drive evaporative desalination. The pure water vapor generated by distillation is then compressed and condensed using an advanced compressor. The compression process improves distillation efficiency by creating the reduced pressure in the evaporation chamber. The compressor centrifuges the pure water vapor after it is drawn through a demister (removing residual impurities) causing it to compress against tubes in the collection chamber. The compression of the vapor causes its temperature to increase. The heat generated is transferred to the input water falling in the tubes, causing the water in the tubes to vaporize. Water vapor condenses on the outside of the tubes as product water. By combining several physical processes, Passarell enables most of the system's energy to be recycled through its subprocesses, namely evaporation, demisting, vapor compression, condensation, and water movement within the system.[52]

Geothermal energy can drive desalination. In most locations, geothermal desalination beats using scarce groundwater or surface water, environmentally and economically.[citation needed]

Nanotube membranes may prove to be effective for water filtration and desalination processes that would require substantially less energy than reverse osmosis.[53]

Hermetic, sulphonated nano-composite membranes have shown to be capable of cleaning most all forms of contaminated water to the 'parts per billion' level. These nano-materials, using a non-reverse osmosis process, have little or no susceptibility to high salt concentration levels.[54][55][56]

Biomimetic membranes are another approach.[57]

On June 23, 2008, Siemens Water Technologies announced technology based on applying electric fields that purports to desalinate one cubic meter of water while using only 1.5 kWh of energy. If accurate, this process would consume only one-half the energy of other processes.[58] Currently, Oasis Water, which developed the technology, still uses three times that much energy. Researchers at the university of Texas at Austin and the University of Marburg are developing more efficient methods of electrochemically mediated seawater desalination.[59]

Freeze-thaw desalination uses freezing to remove fresh water from frozen seawater.

Membraneless desalination at ambient temperature and pressure using electrokinetic shocks waves has been demonstrated.[60] In this technique anions and cations in salt water are exchanged for carbonate anions and calcium cations respectively using electrokinetic shockwaves. Calcium and carbonate ions then react to form calcium carbonate, which then precipitates leaving behind fresh water. Theoretical energy efficiency of this method is on par with electrodialysis and reverse osmosis.

In 2009, Lux Research estimated the worldwide desalinated water supply will triple between 2008 and 2020.[61]

Desalination through evaporation and condensation for crops

The Seawater greenhouse uses natural evaporation and condensation processes inside a greenhouse powered by solar energy to grow crops in arid coastal land.

Low-temperature thermal desalination

Originally stemming from ocean thermal energy conversion research, low-temperature thermal desalination (LTTD) takes advantage of water boiling at low pressures, potentially even at ambient temperature. The system uses vacuum pumps to create a low-pressure, low-temperature environment in which water boils at a temperature gradient of 8–10 °C (46–50 °F) between two volumes of water. Cooling ocean water is supplied from depths of up to 600 m (2,000 ft). This cold water is pumped through coils to condense the water vapor. The resulting condensate is purified water. LTTD may also take advantage of the temperature gradient available at power plants, where large quantities of warm wastewater are discharged from the plant, reducing the energy input needed to create a temperature gradient.[62]

Experiments were conducted in the US and Japan to test the approach. In Japan, a spray-flash evaporation system was tested by Saga University.[63] In Hawaii, the National Energy Laboratory tested an open-cycle OTEC plant with fresh water and power production using a temperature difference of 20 C° between surface water and water at a depth of around 500 m (1,600 ft). LTTD was studied by India's National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT) from 2004. Their first LTTD plant opened in 2005 at Kavaratti in the Lakshadweep islands. The plant's capacity is 100,000 L (22,000 imp gal; 26,000 US gal)/day, at a capital cost of INR 50 million (€922,000). The plant uses deep water at a temperature of 7 to 15 °C (45 to 59 °F).[64] In 2007, NIOT opened an experimental, floating LTTD plant off the coast of Chennai, with a capacity of 1,000,000 L (220,000 imp gal; 260,000 US gal)/day. A smaller plant was established in 2009 at the North Chennai Thermal Power Station to prove the LTTD application where power plant cooling water is available.[62][65][66]

Thermoionic process

In October 2009, Saltworks Technologies, a Canadian firm, announced a process that uses solar or other thermal heat to drive an ionic current that removes all sodium and chlorine ions from the water using ion-exchange membranes.[67]

Existing facilities and facilities under construction

Estimates vary widely between 15,000-20,000 desalination plants producing more than 20,000 m3/day. Micro desalination plants are in operation nearly every where there is a natural gas or fracking facility in the United States.

Algeria

Believed to have at least 15 desalination plants in operation

- Arzew IWPP Power & Desalination Plant, Arzew

- Cap Djinet Seawater Reverse Osmosis(SWRO) 100,000 m3/d[68]

- Tlemcen Souk Tleta 200,000 m3/day

- Tlemcen Hounaine 200,000 m3/day

- Beni Saf 200,000 m3/day

- Tenes 200,000 m3/day

- Fouka 120,000 m3/day

- Skikda 100,000 m3/day

- Hamma Seawater Desalination Plant 200,000 m3/day built by GE [69]

- Mostaganem, once considered the largest in Africa[70]

- Magtaa Reverse Osmosis (RO) Desalination Plant, Oran, Algeria

Aruba

The island of Aruba has a large (world’s largest at the time of its inauguration) desalination plant, with a total installed capacity of 11.1×106 US gallons (4.2×104 m3) per day.[71][dead link]

Australia

The Millenium Drought (1997-2009) led to a water supply crisis across much of the country. As a result many desalination plants were built for the first time (see list).

A combination of increased water usage and lower rainfall/drought in Australia caused state governments to turn to desalination, including the recently commissioned Kurnell Desalination Plant serving the Sydney area. While desalination helped secure water supplies, it is energy intensive (~$140/ML) and has a high carbon footprint due to Australia's coal-based energy supply.[citation needed] In 2010, a Seawater Greenhouse went into operation in Port Augusta.[72][73][74]

Bahrain

Completed in 2000, the Al Hidd Desalination Plant on Muharraq island employed a multistage flash process, and produces 272,760 m3 (9,632,000 cu ft) per day.[75] The Al Hidd distillate forwarding station provides 410 million liters of distillate water storage in a series of 45-million-liter steel tanks. A 135-million-liters/day forwarding pumping station sends flows to the Hidd, Muharraq, Hoora, Sanabis, and Seef blending stations, and which has an option for gravity supply for low flows to blending pumps and pumps which forward to Janusan, Budiya and Saar.[76]

Upon completion of the third construction phase, the Durrat Al Bahrain seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) desalination plant was planned to have a capacity of 36,000 cubic meters of potable water per day to serve the irrigation needs of the Durrat Al Bahrain development.[77] The Bahrain-based utility company, Energy Central Co contracted to design, build and operate the plant.[78]

Chile

- Copiapó Desalination Plant[79]

China

China operates the Beijing Desalination Plant in Tianjin, a combination desalination and coal-fired power plant designed to alleviate Tianjin's critical water shortage. Though the facility has the capacity to produce 200,000 cubic meters of potable water per day, it has never operated at more than one-quarter capacity due to difficulties with local utility companies and an inadequate local infrastructure.[80]

Cyprus

A plant operates in Cyprus near the town of Larnaca.[81] The Dhekelia Desalination Plant uses the reverse osmosis system.[82]

Egypt

- Dahab RO Desalination Plants Dahab 3,600 m3/day completed 1999

- Hurgada and Sharm El-Sheikh Power and Desalination Plants

- Oyoun Moussa Power and Desalination

- Zaafarana Power and Desalination

Gibraltar

Fresh water in Gibraltar is supplied by a number of reverse osmosis and multistage flash desalination plants.[83] A demonstration forward osmosis desalination plant also operates there.[84]

Grand Cayman

- West Bay, West Bay, Grand Cayman[85]

- Abel Castillo Water Works, Governor's Harbour, Grand Cayman[86]

- Britannia, Seven Mile Beach, Grand Cayman[87]

Hong Kong

The HK Water Supplies Department had pilot desalination plants in Tuen Mun and Ap Lei Chau using reverse osmosis technology. The production cost was at HK$7.8 to HK$8.4 /m3.[88][89] In 2011, the government announced a feasibility study whether to build a desalination plant in Tseung Kwan O.[90] Hong Kong used to have a desalination plant in Lok On Pai.[91]

India

The largest desalination plant in South Asia is the Minjur Desalination Plant near Chennai in India, which produces 36.5 million cubic meters of water per year.[92][93]

A second plant at Nemmeli, Chennai is expected to reach full capacity of 100 million litres of sea-water per day in March 2013.[94]

Iran

An assumption is that around 400,000 m3/d of historic and newly installed capacity is operational in Iran.[95] In terms of technology, Iran’s existing desalination plants use a mix of thermal processes and RO. MSF is the most widely used thermal technology although MED and vapour compression (VC) also feature.[95]

Israel

Israel Desalination Enterprises’ Sorek Desalination Plant in Palmachim provides up to 26,000 m³ of potable water per hour (2.300 m³ p.a.). At full capacity, it is the largest desalination plant of its kind in the world.[96]

The Hadera seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) desalination plant in Israel is the largest of its kind in the world.[97][98] The project was developed as a build–operate–transfer by a consortium of two Israeli companies: Shikun and Binui, and IDE Technologies.[99]

| Location | Opened | Capacity (million m3/year) |

Cost of water (per m3) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashkelon | August 2005 | 120 (as of 2010) | NIS 2.60 | [101] |

| Palmachim | May 2007 | 45 | NIS 2.90 | [102] |

| Hadera | December 2009 | 127 | NIS 2.60 | [103] |

| Location | Opening | Capacity (million m3/year) |

Cost of water (per m3) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashdod | 2013 | 100 (expansion up to 150 possible) | NIS 2.40 | [104] |

| Soreq | 2013 | 150 (expansion up to 300 approved) | NIS 2.01 – 2.19 | [105] |

Malta

Ghar Lapsi II 50,000 m3/day[106]

Oman

A pilot seawater greenhouse was built in 2004 near Muscat, in collaboration with Sultan Qaboos University, providing a sustainable horticultural sector on the Batinah coast.[107]

- Ghubrah Power & Desalination Plant, Muscat

- Sohar Power & Desalination Plant, Sohar

- Sur R.O. Desalination Plant 80,000 m3/day 2009[108]

- Qarn Alam 1000 m3/day

- Wilayat Diba 2000 m3/day

There are at least two forward osmosis plants operating in Oman

Saudi Arabia

The Saline Water Conversion Corporation of Saudi Arabia provides 50% of the municipal water in the Kingdom, operates a number of desalination plants, and has contracted $1.892 billion [111] to a Japanese-South Korean consortium to build a new facility capable of producing a billion liters per day, opening at the end of 2013. They currently operate 32 plants in the Kingdom;[112] one example at Shoaiba cost $1.06 billion and produces 450 million liters per day.[113]

- Corniche RO Plant (Crop) (operated by SAWACO)

- Jubail 800,000 m3/day[114]

- North Obhor Plant (operated by SAWACO)

- Rabigh 7,000 m3/day (operated by wetico)

- planned for completion 2018 Rabigh II 600,000 m3/day (under construction Saline Water Conversion Corporation)[115]

- Shuaibah III 150,000 m3/day (operated by Doosan)

- South Jeddah Corniche Plant (SOJECO) (operated by SAWACO)

- Yanbu Multi Effect Distillation (MED), Saudi Arabia 68,190 m3/day

South Africa

- Richards Bay Desalination Plant 100,000 m3/day

Spain

Lanzarote is the easternmost of the autonomous Canary Islands. It is the driest of the islands, of volcanic origin and has limited water supplies. A private, commercial desalination plant was installed in 1964. This served the whole island and enabled the tourism industry. In 1974, the venture was injected with investments from local and municipal governments and a larger infrastructure was put in place. In 1989, the Lanzarote Island Waters Consortium (INALSA)[116] was formed.

A prototype seawater greenhouse was constructed in Tenerife in 1992.[117]

- Alicante II 65,000 m3/day (operator Inima)

- Tordera 60,000 m3/day

- Barcelona 200,000 m3/day (operator Degremont) El Prat, near Barcelona, a desalination plant completed in 2009 was meant to provide water to the Barcelona metropolitan area, especially during the periodic severe droughts that put the available amounts of drinking water under serious stress.

- Oropesa 50,000 m3/day (operator TECNICAS REUNIDAS)

- Moncofa 60,000 m3/day (operator Inima)

- Marina Baja - Mutxamel 50,000 m3/day (operator Degremont)

- Torrevieja 240,000 m3/day (operator ACCIONA)

- Cartagena Escombreras 63,000 m3/day (operator COBRA | TEDAGUA)

- Edam Ibiza + Edam San Antonio 25,000 m3/day (operator Ibiza - Portmany)

- Mazarron 36,000 m3/day (operator TEDAGUA)

- Bajo Almanzora 65,000 m3/day

United Arab Emirates

The Jebel Ali desalination plant in Dubai, a dual-purpose facility, uses multistage flash distillation and is capable of producing 300 million cubic meters of water per year[citation needed].

- Kalba 15,000 m3/day built for Sharjah Electricity and Water Authority completed 2010(operator CH2MHill)[118]

- Khor Fakkan 22,500 m3/day (operator CH2MHill)

- Ghalilah RAK 68,000 m3/day (operator AQUATECH)

- Hamriyah 90,000 m3/day (operator AQUA Engineering)

- Taweelah A1 Power and Desalination Plant has an output 385,000,000 L (85,000,000 imp gal; 102,000,000 US gal) per day of clean water.

- Al Zawrah 27,000 m3/day (operator Aqua Engineering)

- Layyah I 22,500 m3/day (operator CH2MHill)

- Emayil & Saydiat Island ~20,000 m3/day (operator Aqua EPC)

- Umm Al Nar Desalination Plant has an output of 394,000,000 L (87,000,000 imp gal; 104,000,000 US gal)/day.

- Al Yasat Al Soghrih Island 2M gallons per day (GPD) or 9,000 m3/day

- Fujairah F2 is to be completed by July 2010 will have a water production capacity of 492,000,000 L (108,000,000 imp gal; 130,000,000 US gal) per day.[119]

- A seawater greenhouse was constructed on Al-Aryam Island, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates in 2000.

United Kingdom

The first large-scale plant in the United Kingdom, the Thames Water Desalination Plant, was built in Beckton, east London for Thames Water by Acciona Agua.[120]

Jersey

The desalination plant located near La Rosière, Corbiere, Jersey, is operated by Jersey Water. Built in 1970 in an abandoned quarry, it was the first in the British Isles.

The original plant used a multistage flash (MSF) distillation process, whereby seawater was boiled under vacuum, evaporated and condensed into a freshwater distillate. In 1997, the MSF plant reached the end of its operational life and was replaced with a modern reverse osmosis plant.

Its maximum power demand is 1,750 kW, and the output capacity is 6,000 cubic meters per day. Specific energy consumption is 6.8 kWh/m3.[121]

United States

Texas

There are a dozen different desalination projects in the State of Texas, both for desalinating groundwater and desalinating seawater from the Gulf of Mexico.[122][123]

El Paso

Brackish groundwater has been treated at the El Paso, Texas, plant since around 2004. It produces 27,500,000 US gallons (104,000,000 L; 22,900,000 imp gal) of fresh water daily (about 25% of total freshwater deliveries) by reverse osmosis.[124]

The plant’s water cost — largely representing the cost of energy — is about 2.1 times higher than ordinary groundwater production. On average, the plant produces 3.5 million gallons per day (about 11 acre-feet) at an average production cost of $489 per acre-foot. [125]

California

Carlsbad

The United States' largest desalination plant is being constructed by Poseidon Resources and is expected to go online 2016.[126]

Santa Barbara

The Charles Meyer Desalination Facility[127] was constructed in Santa Barbara, California, in 1991–92 as a temporary emergency water supply in response to severe drought. While it has a high operating cost, the facility only needs to operate infrequently, allowing Santa Barbara to use its other supplies more extensively.

Florida

Florida has five (5) water management districts. These are (North to South):[128]

- Northwest Florida WMD [129]

- Suwannee River WMD [130]

- Saint Johns WMD [131] Provides map of districts. Serves Jacksonville to Vero Beach.

- Southwest Florida WMD [132]

- South Florida WMD [133] Serves Orlando.

The St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) provides a presentation (PDF) of the desalanation process.[134]

As of 2012, South Florida has 33 brackish and two seawater desalination plants operating with seven brackish water plants under construction. The brackish and seawater desalination plants have the capacity to produce 245 million gallons of potable water per day.[135]

Tampa Bay

The Tampa Bay Water desalination project near Tampa, Florida, was originally a private venture led by Poseidon Resources, but it was delayed by the bankruptcy of Poseidon Resources' successive partners in the venture, Stone & Webster, then Covanta (formerly Ogden) and its principal subcontractor, Hydranautics. Stone & Webster declared bankruptcy June 2000. Covanta and Hydranautics joined in 2001, but Covanta failed to complete the construction bonding, and then the Tampa Bay Water agency purchased the project on May 15, 2002, underwriting the project. Tampa Bay Water then contracted with Covanta Tampa Construction, which produced a project that failed performance tests. After its parent went bankrupt, Covanta also filed for bankruptcy prior to performing renovations that would have satisfied contractual agreements. This resulted in nearly six months of litigation. In 2004, Tampa Bay Water hired a renovation team, American Water/Acciona Aqua, to bring the plant to its original, anticipated design. The plant was deemed fully operational in 2007,[37] and is designed to run at a maximum capacity of 25 million US gallons (95,000 m3) per day.[136] The plant can now produce up to 25 million US gallons (95,000 m3) per day when needed.[137]

Arizona

Yuma

The desalination plant in Yuma, Arizona, was constructed under authority of the Federal Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Act of 1974 to treat saline agricultural return flows from the Wellton-Mohawk Irrigation and Drainage District into the Colorado River. The treated water is intended for inclusion in water deliveries to Mexico, thereby keeping a like amount of freshwater in Lake Mead, Arizona and Nevada. Construction of the plant was completed in 1992, and it has operated on two occasions since then. The plant has been maintained, but largely not operated due to sufficient freshwater supplies from the upper Colorado River.[138]

An agreement was reached in April 2010 between the Southern Nevada Water Authority, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, the Central Arizona Project, and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to underwrite the cost of running the plant in a year-long pilot project.[139]

Trinidad and Tobago

The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago uses desalination to open up more of the island's water supply for drinking purposes. The country's desalination plant, opened in March 2003, is considered to be the first of its kind. It was the largest desalination facility in the Americas, and it processes 28,800,000 US gallons (109,000 m3) of water a day at the price of $2.67 per 1,000 US gallons (3.8 m3).[140]

This plant will be located at Trinidad's Point Lisas Industrial Estate, a park of more than 12 companies in various manufacturing and processing functions, and it will allow for easy access to water for both factories and residents in the country.[141]

In nature

Evaporation of water over the oceans in the water cycle is a natural desalination process.

The formation of sea ice is also a process of desalination. Salt is expelled from seawater when it freezes. Although some brine is trapped, the overall salinity of sea ice is much lower than seawater.

Seabirds distill seawater using countercurrent exchange in a gland with a rete mirabile. The gland secretes highly concentrated brine stored near the nostrils above the beak. The bird then "sneezes" the brine out. As freshwater is not available in their environments, some seabirds, such as pelicans, petrels, albatrosses, gulls and terns, possess this gland, which allows them to drink the salty water from their environments while they are hundreds miles away from land.[142][143]

Mangrove trees grow in seawater; they secrete salt by trapping it into parts of the root, which are then eaten by animals (usually crabs). Additional salt removal is done by storing it in leaves which then fall off. Some types of mangroves have glands on their leaves, which work in a similar way to the seabird desalination gland. Salt is extracted to the leaf exterior as small crystals, which then fall off the leaf.

Willow trees and reeds are known to absorb salt and other contaminants, effectively desalinating the water. This is used in artificial constructed wetlands, for treating sewage.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ "Desalination" (definition), The American Heritage Science Dictionary, Houghton Mifflin Company, via dictionary.com. Retrieved on 2007-08-19.

- ^ "Australia Aids China In Water Management Project." People's Daily Online, 2001-08-03, via english.people.com.cn. Retrieved on 2007-08-19.

- ^ Fischetti, Mark (September 2007). "Fresh from the Sea". Scientific American. 297 (3): 118–119. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0907-118. PMID 17784633.

- ^ "Finding Water in Mogadishu"IPS news item 2008

- ^ "Energy Efficient Reverse Osmosis Desalination Process", p343 Table 1, International Journal of Environmental Science and Development, Vol. 3, No. 4, August 2012

- ^ "Analysis of the Energy Intensity of Water Supplies for West Basin Municipal Water District", Table on p4, Robert C. Wilkinson Ph.D, March 2007

- ^ "U.S.Electricity Consumption for Water Supply & Treatment", p1-4 Table 1-1, Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) Water & Sustainability (Volume 4), 2000

- ^ "Seawater Desalination", p12 et seq, Menachem Elimelech, 2012

- ^ "Optimizing Lower Energy Seawater Desalination", p6 figure 1.2, Stephen Dundorf at the IDA World Congress November 2009

- ^ "Membrane Desalination Power Usage Put In Perspective" , American Membrane Technology Association(AMTA) April 2009

- ^ "ENERGY REQUIREMENTS OF DESALINATION PROCESSES", Encyclopedia of Desalination and Water Resources (DESWARE), Retrieved on 2013-06-24

- ^ Lisa Henthorne (November 2009). "The Current State of Desalination" (PDF). International Desalination Association. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Opportunities aplenty | H2O Middle East. H2ome.net (2012-02-06). Retrieved on 2012-05-14.

- ^ "Dubai opens UAE's largest desalination plant". april 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Fritzmann, C; Lowenberg, J; Wintgens, T; Melin, T (2007). "State-of-the-art of reverse osmosis desalination". Desalination. 216: 1–76. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2006.12.009.

- ^ Osman A. Hamed (2005). "Overview of hybrid desalination systems – current status and future prospects". Desalination. 186: 207–214. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2005.03.095.

- ^ B.M. Misra and J. Kupitz (2004). "The role of nuclear desalination in meeting potable water needs in water scarce areas in the next decades". Desalination. 166: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2004.06.053.

- ^ Nuclear Desalination. Retrieved on 2010-01-07

- ^ Heinz Ludwig (2004). "Hybrid systems in seawater desalination – practical design aspects, present status and development perspectives". Desalination. 164: 1–18. doi:10.1016/S0011-9164(04)00151-1.

- ^ Tom Harris (2002-08-29) How Aircraft Carriers Work. Howstuffworks.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ "Nuclear Desalination". World Nuclear Association. January 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Barlow, Maude, and Tony Clarke, "Who Owns Water?" The Nation, 2002-09-02, via thenation.com. Retrieved on 2007-08-20.

- ^ Yuan Zhou and Richard S.J. Tol. "Evaluating the costs of desalination and water transport." (Working paper). Hamburg University. 2004-12-09. Retrieved on 2007-08-20.

- ^ Desalination is the Solution to Water Shortages, redOrbit, May 2, 2008

- ^ Sitbon, Shirli. "French-run water plant launched in Israel," European Jewish Press, via ejpress.org, 2005-12-28. Retrieved on 2007-08-20.

- ^ "Black & Veatch-Designed Desalination Plant Wins Global Water Distinction," (Press release). Black & Veatch Ltd., via edie.net, 2006-05-04. Retrieved on 2007-08-20.

- ^ Perth Seawater Desalination Plant, Seawater Reverse Osmosis (SWRO), Kwinana. Water Technology. Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ "Sydney desalination plant to double in size," ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), via abc.net.au, 2007-06-25. Retrieved on 2007-08-20.

- ^ Australia Turns to Desalination by Michael Sullivan and PX Pressure Exchanger energy recovery devices from Energy Recovery Inc. An Environmentally Green Plant Design. Morning Edition, National Public Radio, June 18, 2007

- ^ Fact sheets, Sydney Water

- ^ Water prices to rise and desalination plant set for Port Stanvac|Adelaide Now. News.com.au (2007-12-04). Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Desalination plant for Adelaide. ministers.sa.gov.au. December 5, 2007

- ^ Bernard Humphreys AdelaideNow readers mostly back desalination plant. AdelaideNow. December 6, 2007

- ^ Kranhold, Kathryn. (2008-01-17) Water, Water, Everywhere... – WSJ.com. Online.wsj.com. Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Carlsbad desal plant, pipe costs near $1 billion

- ^ Desalination gets a serious look – Friday, March 21, 2008|2 a.m.. Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ a b Desalination: A Component of the Master Water Plan . tampabaywater.org

- ^ Hydro-Alchemy, Forbes, May 9, 2008

- ^ The Arid West—Where Water Is Scarce – Desalination—a Growing Watersupply Source, Library Index

- ^ UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT August Term, 2005. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ Heather Cooley, Peter H. Gleick, and Gary Wolff DESALINATION, WITH A GRAIN OF SALT. A California Perspective, Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environment, and Security, June 2006 ISBN 1-893790-13-4

- ^ Australia Turns to Desalination Amid Water Shortage. NPR. Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Lattemann, Sabine; Höpner, Thomas (2008). "Environmental impact and impact assessment of seawater desalination" (PDF). Desalination. 220: 1. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2007.03.009.

- ^ Desalination without brine discharge – Integrated Biotectural System, by Nicol-André Berdellé, 02.20.2011

- ^ Gleick, Peter H., Dana Haasz, Christine Henges-Jeck, Veena Srinivasan, Gary Wolff, Katherine Kao Cushing, and Amardip Mann. (November 2003.) "Waste not, want not: The potential for urban water conservation in California." (Website). Pacific Institute. Retrieved on 2007-09-20.

- ^ Cooley, Heather, Peter H. Gleick, and Gary Wolff. (June 2006.) "Desalination, With a Grain of Salt – A California Perspective." (Website). Pacific Institute. Retrieved on 2007-09-20.

- ^ Gleick, Peter H., Heather Cooley, David Groves. (September 2005.) "California water 2030: An efficient future.". Pacific Institute. Retrieved on 2007-09-20.

- ^ Sun Belt Inc. Legal Documents. Sunbeltwater.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ "FO plant completes 1-year of operation" (PDF). Water Desalination Report: 2–3. 15 Nov 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Modern Water taps demand in Middle East" (PDF). The Independent. 23 Nov 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Thompson N.A., Nicoll P.G. (September 2011). "Forward Osmosis Desalination: A Commercial Reality" (PDF). Proceedings of the IDA World Congress. Perth, Western Australia: International Desalination Association.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ The "Passarell" Process. Waterdesalination.com (2004-11-16). Retrieved on 2012-05-14.

- ^ "Nanotube membranes offer possibility of cheaper desalination" (Press release). Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Public Affairs. 2006-05-18. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ^ Cao, Liwei. "Patent US8222346 - Block copolymers and method for making same". Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Wnek, Gary. "Patent US6383391 - Water-and ion-conducting membranes and uses thereof". Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Cao, Liwei (June 5, 2013). "Dais Analytic Corporation Announces Product Sale to Asia, Functional Waste Water Treatment Pilot, and Key Infrastructure Appointments". prnewswire.com. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Sandia National Labs: Desalination and Water Purification: Research and Development". sandia.gov. 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Team wins $4m grant for breakthrough technology in seawater desalination, The Straits Times, June 23, 2008

- ^ "Chemists Work to Desalinate the Ocean for Drinking Water, One Nanoliter at a Time". Science Daily. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ Shkolnikov, Viktor (5 April 2012). "Desalination and hydrogen, chlorine, and sodium hydroxide production via electrophoretic ion exchange and precipitation" (PDF). Stanford Microfluidics Laboratory. doi:10.1039/c2cp42121f. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ A Rising Tide for New Desalinated Water Technologies, MSNBC, March 17, 2009

- ^ a b Sistla, Phanikumar V.S. "Low Temperature Thermal DesalinbationPLants" (PDF). Proceedings of The Eighth (2009) ISOPE Ocean Mining Symposium, Chennai, India, September 20–24, 2009. International Society of Offshore and Polar Engineers. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Haruo Uehara and Tsutomu Nakaoka Development and Prospective of Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion and Spray Flash Evaporator Desalination. ioes.saga-u.ac.jp

- ^ Desalination: India opens world’s first low temperature thermal desalination plant – IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre. Irc.nl (2005-05-31). Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Floating plant, India. Headlinesindia.com (2007-04-18). Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ Tamil Nadu / Chennai News : Low temperature thermal desalination plants mooted. The Hindu (2007-04-21). Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Current thinking, The Economist, October 29, 2009

- ^ "ERI Broadens Its Energy Recovery Footprint in North Africa". http://www.sec.gov/. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "ALGERIA - REVERSE OSMOSIS DESALINATION PLANT". vvsdcn. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Desalination's Fate Across a Troubled MENA". http://www.waterworld.com/. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ W.E.B. Aruba N.V. – Water Plant. Webaruba.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ Sundrop Farms Pty Ltd. Sundropfarms.com.au. Retrieved on 2012-05-14.

- ^ Seawater Greenhouse Australia construction time lapse (2010). Youtube.com. Retrieved on 2012-05-14.

- ^ Seawater Greenhouse Australia on Southern Cross News (2010). Youtube.com. Retrieved on 2012-05-14.

- ^ AL HIDD IWPP – BAHRAIN. sidem-desalination.com

- ^ Al Hidd Desalination Plant. Water Technology. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ Durrat Al Bahrain desalination plant. Water Technology. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ Construction starts on Durrat Al Bahrain desalination plant. Desalination.biz. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ "Copiapó Desalination Plant (Atacama Region, Chile)". ACCIONA. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (2011-01-24). "Can the sea solve China's water crisis?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ Larnaca SWRO Water Desalination Plant. Water Technology. Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Marangou, V; Savvides, K (2001). "First desalination plant in Cyprus — product water aggresivity and corrosion control1" (PDF). Desalination. 138: 251. doi:10.1016/S0011-9164(01)00271-5.

- ^ AquaGib: Gibraltar – Present Plant. Aquagib.gi. Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ "GIBRALTAR PROVING PLANT EXCEEDING EXPECTATIONS" (PDF). Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ "West Bay, Cayman Islands, Caribbean". Consolidated Water. 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Abel Castillo Water Works, Cayman Islands, Caribbean". Consolidated Water. 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Britannia Seawater Reverse Osmosis, Cayman Islands, Caribbean". Consolidated Water. 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ LCQ5 : Study on desalination. info.gov.hk (2007-01-10)

- ^ Pilot Plant Study on Development of Desalination Facilities in Hong Kong. Water Supplies Department, Government of Hong Kong, October 2007, wsd.gov.hk

- ^ Policy Address 2011

- ^ Advisory Committee on the Quality of Water Supplies Minutes of Meeting No. 8. 1 April 2003. wsd.gov.hk

- ^ "Innovative India water plant opens in Madras". BBC News. 2010-07-30.

- ^ "Minjur desal plant to be inaugurated today". The Times Of India. 2010-07-31.

- ^ "Nemmeli plant brings hope to parched city". The Hindu. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Iran's installed desalination profile". Global Water Intelligence. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ With desalination, a once unthinkable water surplus is possible Extracting the Mediterranean Sea’s water could provide Israel with an unquenchable supply of the resource it lacks, Ben Sales, May 30, 2013, Times of Israel, same in Water surplus in Israel? With desalination, once unthinkable is possible

- ^ Israel is No. 5 on Top 10 Cleantech List in Israel 21c A Focus Beyond Retrieved 2009-12-21

- ^ Ashkelon Desalination Plant Seawater Reverse Osmosis (SWRO) Plant. Water-technology.net. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ Sauvetgoichon, B (2007). "Ashkelon desalination plant — A successful challenge". Desalination. 203: 75–81. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2006.03.525.

- ^ Public-Private Partnership Projects, Accountant General, Ministry of Finance

- ^ water-technology.net:"Ashkelon Desalination Plant Seawater Reverse Osmosis (SWRO) Plant, Israel"

- ^ Globes Business and Technology News:"Palmachim desalination plant inaugurates expansion", November 17, 2010

- ^ Globes Business and Technology News:"Funding agreed for expanding Hadera desalination plant", November 6, 2009

- ^ Globes Business and Technology News:"Mekorot wins battle to build Ashdod desalination plant", February 22, 2011

- ^ Desalination & Water Reuse:"IDE reported winner of Soreq desalination contract", 15 December 2009

- ^ Map of Our Global Installations. "Map of Our Global Installations". Energy Recovery. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Seawater Greenhouse wins Tech Awards (2006, Oman & Tenerife). Youtube.com. Retrieved on 2012-05-14.

- ^ David, Boris. "Beach Wells for Large-Scale Reverse Osmosis Plants: The Sur Case Study" (PDF). Veolia Water. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "Second forward osmosis facility completed in Oman". Water World. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Modern Water MOD plant begins operation in Oman". Filtration + Separation. 13 November 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Sasakura, Samsung $1.89bn bid lowest for Saudi plant. Reuters.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ "Dow and Saudi Saline Water Conversion Corporation Sign Commercial Agreement for Research Collaboration". DOW. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Map on this page. Saudi Arabian plants Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ Picow, Maurice. "Saudi Arabia Opens World's Largest Desalination Plant". Green Prophet. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "High-capacity desalination plant planned in Rabigh". Saudi Gazette. Retrieved 27

February 2013.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); line feed character in|accessdate=at position 3 (help) - ^ INSULAR DE AGUAS DE LANZAROTE S.A.. INALSA Retrieved on 2011-07-05.

- ^ Seawater Greenhouse Pilot Project – Canary Islands (1994). Youtube.com. Retrieved on 2012-05-14.

- ^ "SEWA Seawater Reverse Osmosis Plant" (PDF). CH2MHill. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Abu Dhabi to Build Three Power and Water Desalination Plants by 2016 to Meet Demand. industrialinfo.com (2009-11-18). Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Thames Water Desalination Plant. water-technology.net. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ "raw water processing plant". Jerseywater.je. 1999-07-09. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ^ Desalination Facts. Texas Water Development Board

- ^ Desalination Projects. Texas Water Development Board

- ^ El Paso Water Utilities – Public Service Board|Desalination Plant. Epwu.org. Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Texas Water Report: Going Deeper for the Solution. Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts. Retrieved on 2013-02-10

- ^ Boxall, Bettina. "Seawater desalination plant might be just a drop in the bucket". LA Times. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Charles Meyer Desalination Facility. santabarbaraca.gov. Retrieved on 2014-02-14.

- ^ http://floridaswater.com/maps.html

- ^ http://www.nwfwmd.state.fl.us/

- ^ http://www.srwmd.state.fl.us/

- ^ http://floridaswater.com/

- ^ http://www.swfwmd.state.fl.us/

- ^ http://www.sfwmd.gov/portal/page/portal/sfwmdmain/home%20page

- ^ http://floridaswater.com/technicalreports/pdfs/SP/SJ2004-SP7.pdf

- ^ http://www.sfwmd.gov/portal/page/portal/xweb%20-%20release%203%20water%20supply/desalination

- ^ Tampa Bay Seawater Desalination Plant. Tampabaywater.org. Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Richard Danielson (February 16, 2010) Tampa Bay Water stands to get $31 million for reaching milestones at desal plant – St. Petersburg Times. Tampabay.com. Retrieved on 2012-07-13.

- ^ "Yuma Desalting Plant" U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, retrieved May 1, 2010

- ^ "A fresh start for Yuma desalting plant" Los Angeles Times, May 1, 2010

- ^ Ionics to build $120M desalination plant in Trinidad|Boston Business Journal. Bizjournals.com. Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Trinidad Desalination Plant. Waterindustry.org (2000-10-26). Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- ^ Proctor, Noble S.; Lynch, Patrick J. (1993). Manual of Ornithology. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300076193.

- ^ Ritchison, Gary. "Avian osmoregulation". Retrieved 16 April 2011. including images of the gland and its function

Further reading

- Committee on Advancing Desalination Technology, National Research Council. (2008). Desalination: A National Perspective. National Academies Press.

Articles

- Desalination: The next wave in global water consumption from TLVInsider

- Elimelech, M.; Phillip, W. A. (2011). "The Future of Seawater Desalination: Energy, Technology, and the Environment" (PDF). Science. 333 (6043): 712–717. doi:10.1126/science.1200488. PMID 21817042. Significant review article.

External links

- International Desalination Association

- Desalination timeline

- Examples of sea water desalination plants by the WWWS AG

- GeoNoria Solar Desalination Process

- National Academies Press|Desalination: A National Perspective

- World Wildlife Fund|Desalination: option or distraction?

- European Desalination Society

- IAEA – Nuclear Desalination

- DME – German Desalination Society

- Large scale desalination of sea water using solar energy

- Desalination by humidification and dehumidification of air: state of the art

- Zonnewater – optimized solar thermal desalination (distillation)

- SOLAR TOWER Project – Clean Electricity Generation for Desalination.

- Desalination bibliography Library of Congress

- Water-Technology

- Cheap Drinking Water from the Ocean – Carbon nanotube-based membranes will dramatically cut the cost of desalination

- Solar thermal-driven desalination plants based on membrane distillation

- Encyclopedia of Water Sciences, Engineering and Technology Resources

- wind-powered desalinization plant in Perth, Australia, is an example of how technology is insulating rich countries from impacts of climate change, while poor countries remain particularly vulnerable.

- The Desal Response Group

- Encyclopedia of Desalination and water and Water Resources

- Desalination & Water Reuse – Desalination news

- Desalination: The Cyprus Experience

- Desalination: The Jersey Water plant at La Rosière, Corbiere

- Desalination and Membrane Technologies: Federal Research and Adoption Issues Congressional Research Service