Seven deadly sins

The seven deadly sins, also known as the capital vices or cardinal sins, is a classification of vices (part of Christian ethics) that has been used since early Christian times to educate and instruct Christians concerning fallen humanity's tendency to sANOOS, envy, and gluttony.

The Catholic Church divides sin into two categories: venial sins, in which guilt is relatively minor, and the more severe mortal sins. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, a mortal or deadly sin is believed to destroy the life of grace and charity within a person and thus creates the threat of eternal damnation. "Mortal sin, by attacking the vital principle within us – that is, charity – necessitates a new initiative of God's mercy and a conversion of heart which is normally accomplished within the setting of the sacrament of reconciliation."[1]

According to Catholic moral thought, the seven deadly sins are not discrete from other sins, but are instead the origin ("capital" comes from the Latin caput, head) of the others. Vices can be either venial or mortal, depending on the situation, but "are called 'capital' because they engender other sins, other vices".[2]

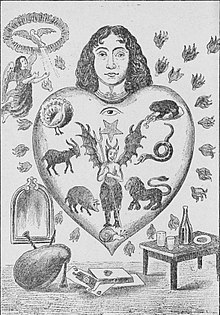

Beginning in the early 14th century, the popularity of the seven deadly sins as a theme among European artists of the time eventually helped to ingrain them in many areas of Catholic culture and Catholic consciousness in general throughout the world. One means of such ingraining was the creation of the mnemonic acronym "SALIGIA" based on the first letters in Latin of the seven deadly sins: superbia, avaritia, luxuria, invidia, gula, ira, acedia.[3]

Biblical lists

In the Book of Proverbs 6:16-19, among the verses traditionally associated with King Solomon, it states that the Lord specifically regards "six things the Lord hateth, and seven that are an abomination unto Him", namely:[4]

- A proud look

- A lying tongue

- Hands that shed innocent blood

- A heart that devises wicked plots

- Feet that are swift to run into mischief

- A deceitful witness that uttereth lies

- Him that soweth discord among brethren

Another list, given this time by the Epistle to the Galatians (Galatians 5:19-21), includes more of the traditional seven sins, although the list is substantially longer: adultery, fornication, uncleanness, lasciviousness, idolatry, sorcery, hatred, variance, emulations, wrath, strife, seditions, heresies, envyings, murders, drunkenness, revellings, "and such like".[5] Since Saint Paul goes on to say that the persons who practice these sins "shall not inherit the Kingdom of God", they are usually listed as (possible) mortal sins rather than capital vices.

History

The modern concept of the seven deadly sins is linked to the works of the 4th century monk Evagrius Ponticus, who listed eight evil thoughts in Greek as follows:[6]

- [Γαστριμαργία] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gk (help) (gastrimargia) gluttony

- [Πορνεία] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gk (help) (porneia) prostitution, fornication

- [Φιλαργυρία] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gk (help) (philargyria) avarice

- [Ὑπερηφανία] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gk (help) (hyperēphania) hubris – in the Philokalia, this term is rendered as self-esteem

- [Λύπη] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gk (help) (lypē) sadness – in the Philokalia, this term is rendered as envy, sadness at another's good fortune

- [Ὀργή] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gk (help) (orgē) wrath

- [Κενοδοξία] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gk (help) (kenodoxia) boasting

- [Ἀκηδία] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gk (help) (akēdia) acedia – in the Philokalia, this term is rendered as dejection

They were translated into the Latin of Western Christianity (largely due to the writings of John Cassian),[7] thus becoming part of the Western tradition's spiritual pietas (or Catholic devotions), as follows:[8]

- Gula (gluttony)

- Fornicatio (fornication, lust)

- Avaritia (avarice/greed)

- Superbia (hubris, pride)

- Tristitia (sorrow/despair/despondency)

- Ira (wrath)

- Vanagloria (vainglory)

- Acedia (sloth)

These "evil thoughts" can be categorized into three types:[8]

- lustful appetite (gluttony, fornication, and avarice)

- irascibility (wrath)

- intellect (vainglory, sorrow, pride, and Discouragement)

In AD 590, a little over two centuries after Evagrius wrote his list, Pope Gregory I revised this list to form the more common Seven Deadly Sins, by folding (sorrow/despair/despondency) into acedia, vainglory into pride, and adding envy.[9] In the order used by Pope Gregory, and repeated by Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) centuries later in his epic poem The Divine Comedy, the seven deadly sins are as follows:

- [luxuria] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (lechery/lust)[10][11][12]

- [gula] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (gluttony)

- [avaritia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (avarice/greed)

- [acedia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (sloth/discouragement)

- [ira] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (wrath)

- [invidia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (envy)

- [superbia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (pride)

The identification and definition of the seven deadly sins over their history has been a fluid process and the idea of what each of the seven actually encompasses has evolved over time. Additionally, as a result of semantic change:

It is this revised list that Dante uses. The process of semantic change has been aided by the fact that the personality traits are not collectively referred to, in either a cohesive or codified manner, by the Bible itself; other literary and ecclesiastical works were instead consulted, as sources from which definitions might be drawn.[citation needed] Part II of Dante's Divine Comedy, Purgatorio, has almost certainly been the best known source since the Renaissance.[citation needed]

The modern Catholic Catechism lists the sins in Latin as "superbia, avaritia, invidia, ira, luxuria, gula, pigritia seu acedia", with an English translation of "pride, avarice, envy, wrath, lust, gluttony, and sloth/acedia".[13] Each of the seven deadly sins now also has an opposite among corresponding seven holy virtues (sometimes also referred to as the contrary virtues). In parallel order to the sins they oppose, the seven holy virtues are humility, charity, kindness, patience, chastity, temperance, and diligence.

Historical and modern definitions

Lust

Lust or lechery (carnal "luxuria") is an intense desire. It is a general term for desire. Therefore lust could involve the intense desire of money, food, fame, power or sex.

In Dante's Purgatorio, the penitent walks within flames to purge himself of lustful thoughts and feelings. In Dante's Inferno, unforgiven souls of the sin of lust are blown about in restless hurricane-like winds symbolic of their own lack of self-control to their lustful passions in earthly life.

Gluttony

(Albert Anker, 1896)

Derived from the Latin gluttire, meaning to gulp down or swallow, gluttony (Latin, [gula] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is the over-indulgence and over-consumption of anything to the point of waste.

In Christianity, it is considered a sin if the excessive desire for food causes it to be withheld from the needy.[14]

Because of these scripts, gluttony can be interpreted as selfishness; essentially placing concern with one's own interests above the well-being or interests of others.

Medieval church leaders (e.g., Thomas Aquinas) took a more expansive view of gluttony,[14] arguing that it could also include an obsessive anticipation of meals, and the constant eating of delicacies and excessively costly foods.[15] Aquinas went so far as to prepare a list of six ways to commit gluttony, comprising:

- Praepropere – eating too soon

- Laute – eating too expensively

- Nimis – eating too much

- Ardenter – eating too eagerly

- Studiose – eating too daintily

- Forente – eating wildly

Greed

Greed (Latin, [avaritia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), also known as avarice, cupidity or covetousness, is, like lust and gluttony, a sin of excess. However, greed (as seen by the church) is applied to a very excessive or rapacious desire and pursuit of material possessions. Thomas Aquinas wrote, "Greed is a sin against God, just as all mortal sins, in as much as man condemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things." In Dante's Purgatory, the penitents were bound and laid face down on the ground for having concentrated too much on earthly thoughts. Scavenging[citation needed] and hoarding of materials or objects, theft and robbery, especially by means of violence, trickery, or manipulation of authority are all actions that may be inspired by Greed. Such misdeeds can include simony, where one attempts to purchase or sell sacraments, including Holy Orders and, therefore, positions of authority in the Church hierarchy.

As defined outside of Christian writings, greed is an inordinate desire to acquire or possess more than one needs, especially with respect to material wealth.[16]

Sloth

Parable of the Wheat and the Tares by Abraham Bloemaert, Walters Art Museum

Sloth (Latin, [Socordia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) can entail different vices. While sloth is sometimes defined as physical laziness, spiritual laziness is emphasized. Failing to develop spiritually is key to becoming guilty of sloth. In the Christian faith, sloth rejects grace and God.

Sloth has also been defined as a failure to do things that one should do. By this definition, evil exists when good men fail to act.

Edmund Burke (1729-1797) wrote "No man, who is not inflamed by vain-glory into enthusiasm, can flatter himself that his single, unsupported, desultory, unsystematic endeavours are of power to defeat the subtle designs and united Cabals of ambitious citizens."When bad men combine, the good must associate; else they will fall, one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle."

Over time, the "acedia" in Pope Gregory's order has come to be closer in meaning to sloth. The focus came to be on the consequences of acedia rather than the cause, and so, by the 17th century, the exact deadly sin referred to was believed to be the failure to utilize one's talents and gifts. [citation needed] Even in Dante's time there were signs of this change; in his Purgatorio he had portrayed the penance for acedia as running continuously at top speed.

Wrath

by Jacob Matham

Wrath (Latin, [ira] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), also known as "rage", may be described as inordinate and uncontrolled feelings of hatred and anger. Wrath, in its purest form, presents with self-destructiveness, violence, and hate that may provoke feuds that can go on for centuries. Wrath may persist long after the person who did another a grievous wrong is dead. Feelings of anger can manifest in different ways, including impatience, revenge, and self-destructive behavior, such as drug abuse or suicide.

Wrath is the only sin not necessarily associated with selfishness or self-interest, although one can of course be wrathful for selfish reasons, such as jealousy (closely related to the sin of envy). Dante described vengeance as "love of justice perverted to revenge and spite". In its original form, the sin of wrath also encompassed anger pointed internally as well as externally. Thus suicide was deemed as the ultimate, albeit tragic, expression of hatred directed inwardly, a final rejection of God's gifts. [citation needed]

Envy

Arch in the nave with a gothic fresco from 1511 of a man with a dog-head, which symbolizes envy (da, Denmark)

Like greed and lust, Envy (Latin, [invidia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is characterized by an insatiable desire. Envy is similar to jealousy in that they both feel discontent towards someone's traits, status, abilities, or rewards. The difference is the envious also desire the entity and covet it.

Envy can be directly related to the Ten Commandments, specifically, "Neither shall you desire... anything that belongs to your neighbour." Dante defined this as "a desire to deprive other men of theirs". In Dante's Purgatory, the punishment for the envious is to have their eyes sewn shut with wire because they have gained sinful pleasure from seeing others brought low. Aquinas described envy as "sorrow for another's good".[17]

Pride

In almost every list, pride (Latin, [superbia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), or hubris (Greek), is considered the original and most serious of the seven deadly sins, and the source of the others. It is identified as believing that one is essentially better than others, failing to acknowledge the accomplishments of others, and excessive admiration of the personal self (especially holding self out of proper position toward God). Dante's definition was "love of self perverted to hatred and contempt for one's neighbour". In Jacob Bidermann's medieval miracle play, Cenodoxus, pride is the deadliest of all the sins and leads directly to the damnation of the titulary famed Parisian doctor. In perhaps the best-known example, the story of Lucifer, pride (his desire to compete with God) was what caused his fall from Heaven, and his resultant transformation into Satan. In Dante's Divine Comedy, the penitents are burdened with stone slabs on their necks which force them to keep their heads bowed.

Historical sins

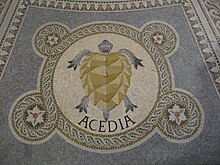

Acedia

mosaic, Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière

Acedia (Latin, [acedia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) (from Greek ἀκηδία) is the neglect to take care of something that one should do. It is translated to apathetic listlessness; depression without joy. It is related to melancholy: acedia describes the behaviour and melancholy suggests the emotion producing it. In early Christian thought, the lack of joy was regarded as a willful refusal to enjoy the goodness of God and the world God created; by contrast, apathy was considered a refusal to help others in time of need.

When Thomas Aquinas described acedia in his interpretation of the list, he described it as an uneasiness of the mind, being a progenitor for lesser sins such as restlessness and instability. Dante refined this definition further, describing acedia as the failure to love God with all one's heart, all one's mind and all one's soul; to him it was the middle sin, the only one characterised by an absence or insufficiency of love. Some scholars[who?] have said that the ultimate form of acedia was despair which leads to suicide.

Vainglory

Vainglory (Latin, [vanagloria] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is unjustified boasting. Pope Gregory viewed it as a form of pride, so he folded vainglory into pride for his listing of sins. [citation needed]

The Latin term gloria roughly means boasting, although its English cognate - glory - has come to have an exclusively positive meaning; historically, vain roughly meant futile, but by the 14th century had come to have the strong narcissistic undertones, of irrelevant accuracy, that it retains today.[18] As a result of these semantic changes, vainglory has become a rarely used word in itself, and is now commonly interpreted as referring to vanity (in its modern narcissistic sense).

Catholic seven virtues

The Catholic Church also recognizes seven virtues, which correspond inversely to each of the seven deadly sins.

| Vice | Latin | Virtue | Latin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lust | Luxuria | Chastity | Castitas |

| Gluttony | Gula | Temperance | Temperantia |

| Greed | Avaritia | Charity | Caritas |

| Sloth | Acedia | Diligence | Industria |

| Wrath | Ira | Patience | Patientia |

| Envy | Invidia | Kindness | Humanitas |

| Pride | Superbia | Humility | Humilitas |

Associations with demons

In 1589, Peter Binsfeld paired each of the deadly sins with a demon, who tempted people by means of the associated sin. According to Binsfeld's classification of demons, the pairings are as follows:

- Lucifer: pride (superbia)

- Mammon: greed (avaritia)

- Asmodeus: lust (luxuria)

- Leviathan: envy (invidia)

- Beelzebub: gluttony (gula or gullia)

- Amon or Satan: wrath (ira)

- Belphegor: sloth (acedia)

This contrasts slightly with an earlier series of pairings found in the fifteenth century English Lollard tract Lanterne of Light, which differs in pairing Leviathan with Envy, Belphegor with Sloth, Beelzebub with Gluttony and matching Lucifer with Pride, Satan with Wrath, Asmodeus with Lust and Mammon with greed.[19]

In Doctor Faustus, there is a "parade" of the seven deadly sins that is conducted by Mephistopheles, Satan, and Beelzebub suggesting that the demons do not match with each deadly sin, but the demons are in command of the seven deadly sins.

Patterns

According to a 2009 study by a Jesuit scholar, the most common deadly sin confessed by men is lust, and for women, pride.[20] It was unclear whether these differences were due to different rates of commission, or different views on what "counts" or should be confessed.[21]

Cultural references

The seven deadly sins have long been a source of inspiration for writers and artists, from medieval works such as Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, to modern works such as the film Se7en and the manga/anime series Fullmetal Alchemist. The ice cream company Walls released a limited edition series of Seven Deadly Sins-inspired Magnum ice creams in 2003.

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, nn.1856. See also nn.1854–1864.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, n. 1866.

- ^ Boyle, Marjorie O'Rourke (1997) [1997-10-23]. "Three: The Flying Serpent". Loyola's Acts: The Rhetoric of the Self. The New Historicism: Studies in Cultural Poetics,. Vol. 36. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 100–146. ISBN 978-0-520-20937-4.

- ^ [bible verse Proverbs 6:16–19]

- ^ Galatians

- ^ Evagrio Pontico,Gli Otto Spiriti Malvagi, trans., Felice Comello, Pratiche Editrice, Parma, 1990, p.11-12.

- ^ Remedies for the Eight Principal Faults

- ^ a b Refoule, 1967

- ^ Introduction to Paulist Press edition of John Climacus: The Ladder of Divine Ascent by Kallistos Ware, p63.

- ^ Godsall-Myers, Jean E. (2003). Speaking in the medieval world. Brill. p. 27. ISBN 90-04-12955-3.

- ^ Katherine Ludwig, Jansen (2001). The making of the Magdalen: preaching and popular devotion in the later Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. p. 168. ISBN 0-691-08987-6.

- ^ Vossler, Karl; Spingarn, Joel Elias (1929). Mediæval Culture: The religious, philosophic, and ethico-political background of the "Divine Comedy". University of Michigan: Constable & company. p. 246.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2008-03-27. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ a b Okholm, Dennis. "Rx for Gluttony". Christianity Today, Vol. 44, No. 10, September 11, 2000, p.62

- ^ "Gluttony". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ "The Free Dictionary". The Free Dictionary. 1987-04-01. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ "Summa Theologica: Treatise on The Theological Virtues (QQ[1] - 46): Question. 36 - Of Envy (four articles)". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ Oxford English dictionary

- ^ Morton W. Bloomfield, The Seven Deadly Sins, Michigan State College Press, 1952, pp.214-215.

- ^ "Two sexes 'sin in different ways'". BBC News. 2009-02-18. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ Morning Edition (2009-02-20). "True Confessions: Men And Women Sin Differently". Npr.org. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- Bibliography

- Refoule, F. (1967) Evagrius Ponticus. In Staff of Catholic University of America (Eds.) New Catholic Encyclopaedia. Volume 5, pp644–645. New York: McGrawHill.

- Schumacher, Meinolf (2005): "Catalogues of Demons as Catalogues of Vices in Medieval German Literature: 'Des Teufels Netz' and the Alexander Romance by Ulrich von Etzenbach." In In the Garden of Evil: The Vices and Culture in the Middle Ages. Edited by Richard Newhauser, pp. 277–290. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies.

Further reading

- The Divine Comedy ("Inferno", "Purgatorio", and "Paradiso"), by Dante Alighieri

- Summa Theologica, by Thomas Aquinas

- The Concept of Sin, by Josef Pieper

- The Traveller's Guide to Hell, by Michael Pauls & Dana Facaros

- Sacred Origins of Profound Things, by Charles Panati

- The Faerie Queene, by Edmund Spenser

- The Seven Deadly Sins Series, Oxford University Press (7 vols.)

- Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung, Glittering Vices: A New Look at the Seven Deadly Sins and Their Remedies, (Grand Rapids: BrazosPress, 2009)

- Solomon Schimmel, The Seven Deadly Sins: Jewish, Christian, and Classical Reflections on Human Psychology, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997)

- "Doctor Faustus" by Christopher Marlowe

External links

- Catholic Catechism on Sin

- Medieval mural depictions - in parish churches of England (online catalog, Anne Marshall, Open University)