Spanking

| Part of a series on |

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

| Campaigns against corporal punishment |

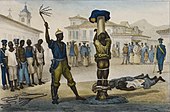

Spanking is the act of striking the buttocks of another person to cause temporary pain without producing physical injury.[1] It generally involves one person striking the buttocks of another person with an open hand. When an open hand is used, spanking is referred to in some countries as slapping or smacking. More severe forms of spanking, such as switching, paddling, belting, caning, whipping, and birching, involve the use of an implement instead of a hand. Corporal punishment is most commonly used to discipline an infant, child, or teenager. It generally involves an adult – typically a parent, guardian, or teacher – striking the child's buttocks as punishment for unacceptable behavior. Historically, boys have tended to be more frequently spanked than girls.[2][3][4][5][6] Some countries have outlawed the spanking of children in every setting, but many allow it at least when administered by a parent or guardian. For the legal status of corporal punishment in different countries, see corporal punishment in the home and school corporal punishment.

In some cultures, the spanking of a wife by her husband is considered an acceptable form of domestic discipline, though the practice is far less common than it used to be.[7] In other contexts, the spanking of an adult can be considered a playful gesture during a social ritual or as a form of entertainment.

Terminology

In North America, the word "spanking" has often been used as a synonym for an official paddling in school,[8] and sometimes even as a euphemism for the formal corporal punishment of adults in an institution.[9]

In British English, most dictionaries define "spanking" as being given only with the open hand.[10]

In American English, dictionaries define spanking as being administered with either the open hand or an implement such as a paddle.[11] Thus, the standard form of corporal punishment in US schools (use of a paddle) is often referred to as a spanking, whereas its pre-1997 English equivalent (strokes of the cane) would never have been so described.

The word "licks" is also a common term in West-Indian countries, especially Trinidad & Tobago. It usually refers to any sort of spanking or beating or really any sort of physical punishment. Licks can involve "switches" or small tree branches, pieces of cocoyea, or basically any sort of object near by. These can also include belts, spoons, brooms, and even rolling pins.

In Britain, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand, the word "smacking" is generally used in preference to "spanking" when describing striking with an open hand, rather than with an implement. Whereas a spanking is invariably administered to the bottom, "smacking" is less specific and may refer to slapping the child's hands, arms or legs as well as its bottom.[12]

In the home

In many cultures, parents have historically been regarded as having the duty of disciplining their children, and the right to spank them when appropriate; however, attitudes in many countries changed in the 1950s and 60s following the publication by pediatrician Dr. Spock of Baby and Child Care in 1946, which advised parents to treat children as individuals, whereas the previous conventional wisdom had been that child rearing should focus on building discipline, and that, e.g., babies should not be "spoiled" by picking them up when they cried. The change in attitude was followed by legislation. According to the CED advocacy group mentioned above, Sweden was the first to abolish corporal punishment of children in the family in 1979. By 2013, 34 countries have abolished corporal punishment of children in the family.[13][14] In Europe, 22 countries have banned the practice. In many other places the practice is considered controversial.

In Africa [citation needed] the Middle East, and in most parts of Eastern Asia (including China, Taiwan, Japan, and Korea), corporal punishment of one's own children is lawful. In Singapore and Hong Kong, punishing one's own child with corporal punishment is legal but not particularly encouraged.[15] Culturally, many people in the region believe a certain amount of corporal punishment for their own children is appropriate and necessary, and thus such practice is accepted by society as a whole.

Lay opinions are divided on whether spanking is helpful or harmful to a child's behavior. Public attitudes towards the acceptability and effectiveness of spanking vary a great deal by nation and region. For example in the United States and United Kingdom, social acceptance of spanking children maintains a majority position, from approximately 61% to 80%.[16][17] In Sweden, before the 1979 ban, more than half of the population considered corporal punishment a necessary part of child rearing. By 1996 the rate was 11%,[18] and less than 34% considered it acceptable in a national survey.[19]

On the other hand, most scientific researchers and child welfare organizations oppose it. Some studies have suggested that it does not benefit the child, and can encourage problems like anxiety, alcohol abuse, or dependence and externalizing problems.[20] Various other problems have also been claimed.[21]

A small minority of researchers have been critical of these studies as scientifically unsound and have pointed out methodological flaws in how they were conducted, as well as the conclusions drawn.[22][23] But even these scientists contend that spanking beyond a specific set of criteria (children age 2–6, no objects, in private, less than once per week) is still harmful.[22]

A longitudinal study by Tulane University in 2010 controlled for a wide variety of confounding variables previously noted and still found negative outcomes in children who were spanked more than twice per month.[24] According to the study's leader, Catherine Taylor, this suggests that "it's not just that children who are more aggressive are more likely to be spanked."[25]

A 2013 meta-analysis by Dr. Chris Ferguson found the effects of spanking and corporal punishment on negative outcomes in children to be trivial or nearly trivial and recommended psychologists take a more nuanced approach to discussing the issue with parents.[26] However, Ferguson acknowledged the limitations of his analysis, stating "Nonetheless, it is worth emphasizing that spanking and CP [(corporal punishment)] do appear to be significantly associated with small increases in negative outcomes, although these correlations may not be as substantial as sometimes implied in public discussions or scholarly comments on the topic." "On the other hand, there was no evidence from the current meta-analysis to indicate that spanking or CP held any particular advantages. There appears, from the current data, to be no reason to believe that spanking/CP holds any benefits related to the current outcomes, in comparison to other forms of discipline."[26]

There is an ongoing debate on whether the sexual deviation "spanking fetishism" is caused by spankings received or witnessed in childhood (or puberty age) or not. A study by Murray Straus found a positive correlation with childhood spanking and adult interest in masochistic sexual practices, but also found that up to 40% of adults with such interests had no history of childhood spanking. This suggests that while spanking may contribute, there are other significant variables involved.[27]

In schools

Corporal punishment, usually delivered with an implement (such as a paddle or cane) rather than with the open hand, used to be a common form of school discipline in many countries, but it is now banned in most of the western world, including all of Europe, and in Japan, Canada, India, New Zealand and South Africa [citation needed]. These bans have been controversial, and in many cultures opinion remains sharply divided as to the efficacy or suitability of spanking as a punishment for misbehaviour by school students.

Formal caning, notably for teenage boys, remains a common form of discipline in schools in several Asian and African [citation needed] countries, especially those with a British heritage such as Malaysia, Singapore, Tanzania and Zimbabwe; however, in these cultures it is referred to as "caning" and not "spanking".

In the United States, the Supreme Court in 1977 held that the paddling of school students was not per se unlawful. The constitutional ban on "cruel and unusual punishment" applied only to those convicted of crime: the common-law stipulation that school corporal punishment be "reasonable and not excessive" was a sufficient safeguard against misuse.[28] However, 31 states have now banned paddling in public schools. Paddling is still common in some schools in the South, where it is often called "spanking".[29][30]

In India, corporal punishment is prohibited in schools in the Right to Free and Compulsory Education Act (2009). Article 17 states: "(1) No child shall be subjected to physical punishment or mental harassment. (2) Whoever contravenes the provisions of sub-section (1) shall be liable to disciplinary action under the service rules applicable to such person."

Adult spanking

In some cultures, the spanking of women, by the male head of the family or by the husband (sometimes called domestic discipline) has been – and sometimes continues to be – a common and approved custom. In those cultures and in those times it was the belief that the husband, as head of the family, had a right and even the duty to discipline his wife and children when he saw fit, and manuals were available to instruct the husband how to discipline his household. In most western countries, this practice has come to be regarded as socially unacceptable wife-beating, domestic violence or abuse. Routine corporal punishment of women by their husbands, however, does still exist in some parts of the developing world,[31][32][33] and still occurs in isolated cases in western countries.

Today, spanking of an adult tends to be confined to erotic spanking between people engaging in other intimate activities, such as foreplay or sexual roleplay.

In popular culture

Adult spanking, or the threat of being spanked, has appeared in numerous films and TV series. In most cases, it is a man spanking or threatening to spank a woman. Some examples include:

- In the 1933 movie Man of the Forest Randolph Scott spanked Verna Hillie over his arm 12 times for trying to take his gun away from him.

- In both the novel Gone With the Wind (1936), and the 1939 film adaptation of it, Rhett Butler pulls Scarlett O'Hara out of bed and spanks her for not getting ready for Melanie's party.

- In the Eroll Flynn film Dodge City (1939), Olivia De Havilland asks what happens to those who object to the face of the law, Flynn replies "We put them across out knees and spank them soundly."

- Yvonne De Carlo was spanked by Rod Cameron in 1945's Frontier Gal.

- The 1953 film version of Kiss Me Kate included a scene with Howard Keel spanking Kathryn Grayson in public view as part of the musical-within-a-film based on Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew. The scene was used in the film's main poster.

- In the 1955 film The Quiet Man, John Wayne spanks Maureen O'Hara. John Wayne also spanks Maureen O'Hara's in The Wings of Eagles (1957).

- In the TV series I Love Lucy (1951–1957), a recurring theme was Lucille Ball's punishment by being spanked by real life and on-screen husband Desi Arnaz for various misdeeds.

- The 1951 film Too Young to Kiss starring June Allyson features a spanking.

- In 1956, Tab Hunter spanked Natalie Wood in The Girl He Left Behind.

- 1959's Holiday for Lovers had Gary Crosby spanking Carol Lynley.

- In 1961's Blue Hawaii, Elvis Presley spanked Jenny Maxwell.

- In 1963, McLintock! included two scenes of adult spanking in which Maureen O'Hara and Stephanie Powers are each spanked with a coal shovel. The scene was used in the promotion of the film: at first a poster with the shovel in hand was used, but after protests, a picture with an open hand replaced the original.

- Also in 1963, John Wayne spanked Elizabeth Allen in Donovan's Reef.

- In Thunderball (1965), James Bond threatens an uncooperative Miss Moneypenny with a spanking over the phone, "Next time I see you, I'll put you across my knee", to which Moneypenny replies, "I can hardly wait." The raising of her eyebrows indicates the threatened spanking is sexual in nature.

- The 1969 western True Grit featured a spanking for Kim Darby; in the 2010 Coen Brothers remake, the young actress Hailee Steinfeld, playing the same role, was also spanked.

- In the TV series Bonanza (1969-1973),the threat of spanking was a common theme which occurred in a number of episodes, including "The Many Faces of Gideon Flinch", and "Woman of Fire". In 1980s the Anne of Green Gables series Anne gets spanked with a horse whip by Gilbert Blythe then he takes her across his knee and spanks her in that position with his hand.

- The 2002 film Secretary is a notable example of a spanking film. It is a dominant/submissive-themed romantic comedy-drama film directed by Steven Shainberg. It stars Maggie Gyllenhaal as Lee Holloway and James Spader as E. Edward Grey. The film is based on a short story from Bad Behavior by Mary Gaitskill.

- In 2003's Kill Bill Volume 1, Uma Thurman spanked a young yakuza.

- In 2007's Shoot 'Em Up, Clive Owen's character sees a mother spanking her son in public. He protects the boy by grabbing the mother and giving her a spanking in front of everyone who was watching.

- In 2012, the TV Series The Big Bang Theory Sheldon spanks Amy after learning that she was pretending to be sick in order to receive more care and attention.

Ritual spanking traditions

There are some rituals or traditions which involve spanking. For example, on the first day of the lunar Chinese new year holidays, a week-long 'Spring Festival', the most important festival for Chinese people all over the world, thousands of Chinese visit the Taoist Dong Lung Gong temple in Tungkang to go through the century-old ritual to get rid of bad luck, men by receiving spankings and women by being whipped, with the number of strokes to be administered (always lightly) by the temple staff being decided in either case by the god Wang Ye and by burning incense and tossing two pieces of wood, after which all go home happily, believing their luck will improve.[34]

On Easter Monday, there is a Slavic tradition of hitting girls and young ladies with woven willow switches (Czech: pomlázka; Slovak: korbáč) and dousing them with water.[35][36][37]

In Slovenia, there is a jocular tradition that anyone who succeeds in climbing to the top of Mount Triglav receives a spanking or birching.[38]

According to Ovid's Fasti (ii.305), during the ancient Roman festival of the Lupercalia naked men ran through the streets of the city, carrying straps with which they swatted the outstretched palms of the hands of women lining the racecourse who wished to become pregnant.

In North America, there is a tradition of "birthday spankings" where the birthday girl or boy receives the same number of hits as her/his age (plus "one to grow on") during the birthday party. Birthday spankings are administered over the clothes and usually by close friends or family members, and are generally playful swats not meant to cause real pain.[citation needed]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Day, R.; Peterson, G. W.; McCracken, C. (1998). "Predicting Spanking of Younger and Older Children by their Mothers and Fathers". Journal of Marriage and the Family. 60 (1): 79–94. doi:10.2307/353443. JSTOR 353443.

- ^ Elder, G.H.; Bowerman, C. E. (1963). "Family Structure and Child Rearing Patterns: The Effect of Family Size and Sex Composition". American Sociological Review. 28 (6): 891–905. doi:10.2307/2090309. JSTOR 2090309.

- ^ Gelles, Richard J.; Straus, Murray A.; Smith, Christine (1995). Physical Violence in American Families: risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. ISBN 1-56000-828-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jacklin, Carol Nagy; Maccoby, Eleanor E. (1978). The Psychology of Sex Differences. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0974-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[page needed] - ^ MacDonald, A. P. (August 1971). "Internal-external locus of control: parental antecedents". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 37 (1): 141–147. doi:10.1037/h0031281. PMID 5565616.

- ^ Straus, Murray A. (1971). "Some Social Antecedents of Physical Punishment: a linkage theory interpretation". Journal of Marriage and the Family. 33 (4): 658–663. doi:10.2307/349438. JSTOR 349438.

- ^ R. Claire Snyder-Hall (2008). "The Ideology of Wifely Submission: A Challenge for Feminism?". Politics & Gender. 4 (4): 563–586. doi:10.1017/S1743923X08000482.

- ^ E.g. "Corporal punishment — spanking or paddling the student — may be used as a discipline management technique ... The instrument to be used in administering corporal punishment shall be approved by the principal or designee".Texas Association of School Boards – Standard Code of Conduct wording.

- ^ See e.g. Evidence of Colonel G. Headly Basher, Deputy Minister for Reform Institutions, Ontario, Joint Committee of the Senate and House of Commons on Capital and Corporal Punishment and Lotteries, Canada, 1953–55.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary: "Spank: To slap or smack (a person, esp. a child) with the open hand." Collins English Dictionary: "Spank: To slap or smack with the open hand, esp. on the buttocks."

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: "Spank: To slap on the buttocks with a flat object or with the open hand, as for punishment."

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary: "Smack: To strike (a person, part of the body, etc.) with the open hand or with something having a flat surface; to slap. Also spec. to chastise (a child) in this manner and fig."

- ^ "The Center for Effective Discipline". EPOCH-USA. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children (GITEACPOC).

- ^ "Singapore's 2nd and 3rd periodic report to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child" (doc). Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports, Singapore. January 2009.

MCYS' brochures on child discipline, "Love our Children, Discipline, Not Abuse", clearly exclude spanking as an option and instead highlights other forms of discipline.

- ^ Reaves, Jessica (5 October 2000). "Survey Gives Children Something to Cry About". Time. New York.

- ^ Bennett, Rosemary (20 September 2006). "Majority of parents admit to smacking children". The Times. London.

- ^ "Corporal Punishment". Encyclopedia.com. 3 September 1955. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ Statistics Sweden. (1996). Spanking and other forms of physical punishment. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden.

- ^ MacMillan, H.L; Boyle, M.H; Wong, M.Ylast5 = Fleming; Walsh, CA (October 1999). "Slapping and spanking in childhood and its association with lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a general population sample". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 161 (7): 805–9. PMC 1230651. PMID 10530296.

{{cite journal}}:|first5=missing|last5=(help); Missing|author5=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Gershoff, Elizabeth T. "Report on Physical Punishment in the United States", Columbus, OH: Center for Effective Discipline.

- ^ a b Baumrind, Diana; Larzelere, Robert E.; Cowan, Philip A. (2002). "Ordinary physical punishment: Is it harmful? Comment on Gershoff (2002)". Psychological Bulletin. 128 (4): 580–9, discussion 602–11. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.580. PMID 12081082.

- ^ Larzelere, Robert E. Ph.D., Letter to the Canadian Senate, June 2005.

- ^ Taylor, CA.; Manganello, JA.; Lee, SJ.; Rice, JC. (May 2010). "Mothers' spanking of 3-year-old children and subsequent risk of children's aggressive behavior". Pediatrics. 125 (5): e1057–65. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2678. PMID 20385647.

- ^ Park, Alice (3 May 2010). "The Long-Term Effects of Spanking". Time. New York.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.002, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.002instead. - ^ Straus, Murray (28 February 2008). "Corporal punishment of children and sexual behavior problems: results from four studies" (PDF). Paper presented at the American Psychological Association Summit Conference on Violence and Abuse in Interpersonal Relationship, Bethesda, Maryland. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ Ingraham v. Wright, 97, S.Ct. 1401 (1977).

- ^ "Corporal Punishment and Paddling Statistics by State and Race", Center for Effective Discipline.

- ^ "External links to present-day school handbooks", World Corporal Punishment Research.

- ^ Beichman, Arnold, "Where wife-beating is up for debate", Washington Times, 2 October 2005.

- ^ Haj-yahia, Muhammad M. (August 2003). "Beliefs About Wife Beating Among Arab Men from Israel: The Influence of Their Patriarchal Ideology". Journal of Family Violence. 18 (4): 193–206. doi:10.1023/A:1024012229984.

- ^ 498A_Crusader (12 December 2007). "Most Indian women okay with wife beating". MyNation Foundation. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)[unreliable source?] - ^ "Ring in the new year with a spanking for luck". Independent Online (South Africa). 26 January 2004.

- ^ Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R. (2004). Encyclopedia of sex and gender: men and women in the world's cultures. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. pp. M1 382. ISBN 0-306-47770-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Montley, Patricia (2005). In Nature's Honor: Myths And Rituals Celebrating The Earth. Boston, MA: Skinner House Books. pp. M1 56. ISBN 1-55896-486-X.

- ^ Knab, Sophie Hodorowicz (1993). Polish customs, traditions, and folklore. New York: Hippocrene. ISBN 0-7818-0068-4.

- ^ Walters, Joanna (12 November 2000). "Reach for the top and a birching". The Guardian. London.