First Opium War

| First Opium War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Opium Wars | |||||||||

The Nemesis destroying Chinese war junks during the Second Battle of Chuenpee, 7 January 1841 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 19,000 troops[2] | 200,000 Bannermen and Green Standard Army troops | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

69 killed 451 wounded | 18,000–20,000 casualties | ||||||||

| Casualties source:[2] | |||||||||

The First Opium War (1839–42), also known as the Opium War and as the Anglo-Chinese War, was fought between Great Britain and China over their conflicting viewpoints on diplomatic relations, trade, and the administration of justice for foreign nationals.[3]

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, Chinese goods, particularly silk, spices and tea, were in high demand in European countries, but the market for Western goods in China was virtually non-existent. This was partly because China was largely self-sufficient and trade laws denied foreigners access to China's interior, but also because the Chinese Emperor banned the trade of most European goods. This left silver and gold as the only acceptable method of payment, causing a silver shortage in Europe and significantly hindering trade.

The trade deficit was alleviated when the Europeans found a product the Chinese consumers did want: highly addictive opium. While this too was banned by the Emperor, smuggling was rampant,[4] and the silver deficit was quickly reduced and eventually reversed. However, this new trade increased the number of opium addicts, which greatly concerned successive emperors.

Before the conflict, Chinese officials attempted to end the spread of opium, and confiscated around 20,000 chests of opium (approximately 1210 t or 2.66 million lb)[5] from British traders. The British government, although not officially denying China's right to control imports of the drug, objected to this seizure and used its military power to enforce violent redress.[3]

The British government objected to the Chinese Empire's insistence on negotiating with all foreign representatives, including Britain's diplomats, on the basis that they were foreign barbarians accepting a position of submission, an assertion which the British never formally accepted but had to work around and overlook. This seriously damaged British attempts to use diplomacy to negotiate and thus prevent conflict, and it was only after the war that China adopted an internationally normal attitude to diplomacy and accepted the political legitimacy and equal sovereignty of foreign nations.

In 1842, the Treaty of Nanking—the first of what the Chinese later called the unequal treaties—granted an indemnity and extraterritoriality to Britain, the opening of five treaty ports, and the cession of Hong Kong Island, thereby ending the trade monopoly of the Canton System. The failure of the treaty to satisfy British goals of improved trade and diplomatic relations led to the Second Opium War (1856–60).[6] The war is now considered in China as the beginning of modern Chinese history.[7][8]

Background - European trade with Asia

Direct maritime trade between Europe and China began in 1557 when the Portuguese leased an outpost at Macau. Other European nations soon followed the Portuguese lead, inserting themselves into the existing Asian maritime trade network to compete with Arab, Chinese, Indian, and Japanese traders in intra-regional trade.[9] Mercantilist governments in Europe objected to the perpetual drain of silver to pay for Asian commodities, and so European traders often sought to generate profits from intra-regional Asian trade to pay for their purchases to be sent back home.[9]

After the Spanish acquisition of the Philippines, the exchange of goods between China and western Europe accelerated dramatically. From 1565, the annual Manila Galleon brought in enormous amounts of silver to the Asian trade network, and in particular China, from Spanish silver mines in South America. As demand increased in Europe, the profits European traders generated within the Asian trade network, used to purchase Asian goods, were gradually replaced by the direct export of bullion from Europe in exchange for the produce of Asia.[9]

British ships began to appear infrequently around the coasts of China from 1635; without establishing formal relations through the tributary system, British merchants were allowed to trade at the ports of Zhoushan and Xiamen in addition to Guangzhou (Canton).[10]

Trade further benefited after the Qing relaxed maritime trade restrictions in the 1680s, after Taiwan came under Qing control in 1683, and even rhetoric regarding the "tributary status" of Europeans was muted.[10] Guangzhou (Canton) was the port of preference for most foreign trade; ships did try to call at other ports but they did not match the benefits of Guangzhou's geographic position at the mouth of the Pearl river trade network and Guangzhou's long experience in balancing the demands of Beijing with those of Chinese and foreign merchants.[11] From 1700–1842, Guangzhou came to dominate maritime trade with China, and this period became known as the "Canton System".[11]

Official British trade was conducted through the auspices of the British East India Company, which held a royal charter for trade with the Far East. The EIC gradually came to dominate Sino-European trade from its position in India.[12]

From the inception of the Canton System by the Qing dynasty in 1757, trade in goods from China was extremely lucrative for European and Chinese merchants alike. However, foreign traders were only permitted to do business through a body of Chinese merchants known as the Cohong and were restricted to Canton (now known as Guangzhou). Foreigners could only live in one of the Thirteen Factories, near Shameen Island, and were not allowed to enter, much less live or trade in, any other part of China.

While silk, and porcelain drove trade through their popularity in the west, an insatiable demand for tea existed in Britain. However, only silver was accepted in payment by China, which resulted in a chronic trade deficit.[13][14] From the mid-17th century around 28 million kilograms of silver were received by China, principally from European powers, in exchange for Chinese goods.[15]

Britain had been on the gold standard since the 18th century, so it had to purchase silver from continental Europe and Mexico to supply the Chinese appetite for silver.[16] Attempts by a British embassy (led by Macartney in 1793), a Dutch mission (under Van Braam in 1794), Russia's (Golovkin in 1805) and the British again (Amherst in 1816) to negotiate access to the China market were all vetoed by successive Emperors.[14]

British and other Europeans tried to reduce their trade deficits by importing tea from India and other places while the Germans managed to reverse engineer the making of porcelain, but the deficits remained.

By 1817, the British realized they could reduce the trade deficit, as well as turn the Indian colony profitable, by counter-trading in narcotic Indian opium.[17] The Qing administration initially tolerated opium importation because it created an indirect tax on Chinese subjects, while allowing the British to double tea exports from China to England, thereby profiting the monopoly on tea exports held by the Qing imperial treasury and its agents.[18]

Opium was produced in traditionally cotton-growing regions of India under British East India Company monopoly (Bengal) and in the Princely states (Malwa) outside the company's control. Both areas had been hard hit by the introduction of factory-produced cotton cloth, which used cotton grown in Egypt. The opium was auctioned in Calcutta (now known as Kolkata) on the condition that it be shipped by British traders to China. Opium as a medicinal ingredient was documented in texts as early as the Tang dynasty but its recreational use was limited and there were laws against its abuse.

British sales of opium in large amounts began in 1781, and sales increased fivefold between 1821 and 1837 [verification needed]. East India Company ships brought their cargoes to islands off the coast, especially Lintin Island, where Chinese traders with fast and well-armed small boats took the goods for inland distribution.[19]

By 1820 the planting of tea in the Indian and African colonies combined with accelerated opium consumption to reverse the flow of silver, just when the Qing treasury needed to finance suppression of rebellions. The Qing government attempted to end the opium trade, but its efforts were complicated by local officials (including the Governor-general of Canton), who profited greatly from the bribes and taxes involved.[19]

A turning point came in 1834. Free trade reformers in England succeeded in ending the monopoly of the British East India Company under the Charter Act of the previous year, leaving trade in the hands of private entrepreneurs. Americans introduced opium from Turkey, which was of lower quality but cheaper. Competition drove down the price of opium and increased sales.[20]

Napier Affair

In late 1834, to accommodate the revocation of the East India Company's monopoly, the British sent Lord William John Napier to Macau along with John Francis Davis and Sir George Best Robinson, 2nd Baronet as British Superintendents of Trade in China. Napier tried to circumvent the restrictive Canton System that forbade direct contact with Chinese officials by attempting to send a letter directly to the Viceroy of Canton. The Viceroy refused to accept it, and closed trade starting on 2 September of that year. Lord Napier had to return to Macau (where he died a few days later) and, unable to force the matter, the British agreed to resume trade under the old restrictions.

Destruction of opium at Humen

By 1838, the British were selling roughly 1,400 tons of opium per year to China. Legalization of the opium trade was the subject of ongoing debate within the Chinese administration, but it was repeatedly rejected, and as of 1838 the government sentenced native drug traffickers to death.

In 1839, the Daoguang Emperor appointed scholar-official Lin Zexu to the post of Special Imperial Commissioner, with the task of eradicating the opium trade.[21] Lin sent an open letter to Queen Victoria questioning the moral reasoning of the British government. Citing what he understood to be a strict prohibition of the trade within Great Britain, Lin questioned how it could then profit from the drug in China. He wrote: "Your Majesty has not before been thus officially notified, and you may plead ignorance of the severity of our laws, but I now give my assurance that we mean to cut this harmful drug forever."[22] The letter never reached the queen, with one source suggesting that it was lost in transit.[23]

Lin banned the sale of opium and demanded that all supplies of the drug be surrendered to the Chinese authorities. He also closed the channel to Canton, effectively holding British traders hostage in the city.[20] As well as seizing opium supplies in the factories, Chinese troops boarded British ships in international waters outside Chinese jurisdiction, where their cargo was still legal, and destroyed the opium aboard.

The British Superintendent of Trade in China, Charles Elliot, got the British traders to agree to hand over their opium stock with the promise of eventual compensation for their loss from the British government.[20] While this amounted to a tacit acknowledgment that the British government did not disapprove of the trade, it also placed a huge liability on the exchequer. This promise, and the inability of the British government to pay it without causing a political storm, was an important casus belli for the subsequent British offensive.[24]

Overall 20,000 chests[25] (each holding about 55 kilograms[26]) were handed over and destroyed beginning 3 June 1839.[27] After the opium was surrendered, trade was restarted on the strict condition that no more drugs would be smuggled into China. Lin demanded that all merchants sign a bond promising not to deal in opium, under penalty of death.[28] The British officially opposed signing of the bond, but some merchants who did not trade opium, such as Olyphant & Co. were willing to sign.

War

In late October the Thomas Coutts arrived in China and sailed to Canton. This ship was owned by Quakers, who refused to deal in opium. The ship's captain, Warner, believed Elliot had exceeded his legal authority by banning the signing of the "no opium trade" bond.[29] The captain negotiated with the governor of Canton and hoped that all British ships could unload their goods at Chuenpee, an island near Humen.

To prevent other British ships from following the Thomas Coutts, Elliot ordered a blockade of the Pearl River. Fighting began on 3 November 1839, when a second British ship, the Royal Saxon, attempted to sail to Canton. Then the British Royal Navy ships HMS Volage and HMS Hyacinth fired a warning shot at the Royal Saxon.

The Qing navy's official report claimed that the navy attempted to protect the British merchant vessel, also reporting a great victory for that day. In reality, they were out-classed by the Royal Naval vessels and many Chinese ships were sunk.[citation needed] Elliot reported that they were protecting their 29 ships in Chuenpee between the Qing batteries. Elliot knew that the Chinese would reject any contacts with the British and there would eventually be an attack with fire boats. Elliot ordered all ships to leave Chuenpee and head for Tung Lo Wan, 20 miles (30 km) from Macau, but the merchants preferred to harbour in Hong Kong.

In 1840, Elliot asked the Portuguese governor in Macau to let British ships load and unload their goods there in exchange for paying rent and any duties. The governor refused for fear that the Qing Government would discontinue supplying food and other necessities to Macau. On 14 January 1840, the Qing Emperor asked all foreigners in China to halt material assistance to the British in China. In retaliation, the British Government and British East India Company decided that they would attack Canton. The military cost would be paid by the British Government.

Some commentators claim that Lord Palmerston, the British Foreign Secretary, initiated the Opium War to maintain the principle of free trade.[30] Professor Glenn Melancon, for example, argues that the issue in going to war was not opium but Britain's need to uphold its reputation, its honour, and its commitment to global free trade. China was pressing Britain just when the British faced serious pressures in the Near East, on the Indian frontier, and in Latin America. In the end, says Melancon, the government's need to maintain its honour in Britain and prestige abroad forced the decision to go to war.[31]

Critics, however, focused on the immorality of opium. William Ewart Gladstone denounced the war as "unjust and iniquitous" and criticised Lord Palmerston's willingness "to protect an infamous contraband traffic."[32] The public and press in the United States and Britain expressed outrage that Britain was supporting the opium trade. Lord Palmerston justified military action by saying that no one could "say that he honestly believed the motive of the Chinese Government to have been the promotion of moral habits" and that the war was being fought to stem China's balance of payments deficit. John Quincy Adams commented that opium was "a mere incident to the dispute... the cause of the war is the kowtow—the arrogant and insupportable pretensions of China that she will hold commercial intercourse with the rest of mankind not upon terms of equal reciprocity, but upon the insulting and degrading forms of the relations between lord and vassal."[33]

In June 1840, an expeditionary force of British Indian army troops aboard 15 barracks ships, four steam-powered gunboats and 25 smaller boats reached Canton from Singapore.[34] The marines were headed by James Bremer. Bremer demanded the Qing Government compensate the British for losses suffered from interrupted trade.[35]

British military superiority drew heavily on newly applied technology. British warships wrought havoc on coastal towns; the steam ship Nemesis was able to move against the winds and tides and support a gun platform with very heavy guns and congreve rockets. In addition, the British troops were the first to be armed with modern rifles, which fired more rapidly and with greater accuracy than matchlock muskets and artillery wielded by Manchu Bannermen and Han Green Standard Army troops, though Chinese cannons had been in use since previous dynasties.

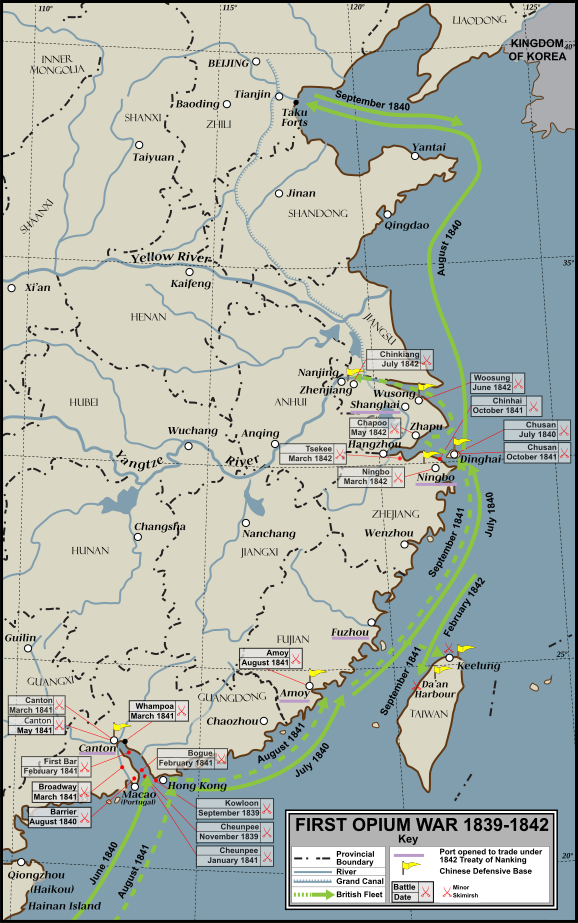

Following the orders of Lord Palmerston, a British expedition blockaded the Mouth of Pearl River and moved north to take Chusan. Led by Commodore J.J. Gordon Bremer in the Wellesley, they captured the empty city after an exchange of gunfire with shore batteries that caused only minor casualties.[35]

The next year, 1841, the British captured the Bogue forts that guarded the mouth of the Pearl River—the waterway between Hong Kong and Canton. Meanwhile, at the far west in Tibet, the start of the Sino-Sikh war added another front to the strained Qing military. By January 1841, British forces commanded the high ground around Canton and defeated Bannermen at Ningbo and at the military post of Dinghai. In the same year the British made three unsuccessful attempts to capture the harbour of Keelung on the northeast coast of Taiwan.[36]

Once the British took Canton, they sailed up the Yangtze and captured the emperor's tax barges, a devastating blow since it slashed the revenue of the imperial court in Beijing to just a fraction of what it had been.

By the middle of 1842, the British had defeated the Chinese at the mouth of their other great riverine trade route, the Yangtze, and occupied Shanghai. The war finally ended in August 1842, with the signing of China's first Unequal Treaty, the Treaty of Nanking.

In the supplementary Treaty of the Bogue, the Qing empire also recognised Britain as an equal to China and gave British subjects extraterritorial privileges in treaty ports. In 1844, the United States and France concluded similar treaties with China, the Treaty of Wanghia and Treaty of Whampoa respectively.

Legacy

The ease with which the British forces defeated the numerically superior Chinese armies seriously affected the Qing Dynasty's prestige. The success of the First Opium War allowed the British to resume the opium trade. It also paved the way for opening of the lucrative Chinese market to other commerce and the opening of Chinese society to missionary endeavors.

Among the most notable figures in the events leading up to the Opium War was the man assigned by the Daoguang Emperor to suppress the opium trade;[37] Lin Zexu, known for his superlative service to the Qing government as "Lin the Clear Sky".[38]

Although he had some initial success, with the arrest of 1,700 opium dealers and the destruction of 1.2 million kilograms (2.6 million lb) of opium, he was made a scapegoat for the actions leading to British retaliation, and was blamed for ultimately failing to stem the tide of opium import and use in China.[39] Nevertheless, Lin Zexu is popularly viewed as a hero of 19th century China, and his likeness has been immortalised at various locations around the world.[40][41][42]

The First Opium War began a long period of weakening of the state.[43] Anti-Qing sentiment grew in the form of rebellions, such as the Taiping Rebellion, a war lasting from 1850–64 in which at least 20 million Chinese died. The decline of the Qing dynasty was beginning to be felt by much of the Chinese population.

Interactive map

See also

Individuals:

Contemporaneous Qing Dynasty wars:

- Sino-Sikh war (1841–1842)

References

- ^ Le Pichon, Alain (2006). China Trade and Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-726337-2.

- ^ a b Martin, Robert Montgomery (1847). China: Political, Commercial, and Social; In an Official Report to Her Majesty's Government. Volume 2. James Madden. pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Tsang, Steve (2007). A Modern History of Hong Kong. I.B.Tauris. p. 3–13, 29. ISBN 1-84511-419-1.

- ^ http://www.forbes.com/sites/investor/2010/11/02/opium-wars-revisited-will-china-corner-the-gold-market/

- ^ Farooqui, Amar (March 2005). Smuggling as Subversion: Colonialism, Indian Merchants, and the Politics of Opium, 1790-1843. Lexington Books. ISBN 0739108867.

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 29

- ^ Stockwell, Foster (2003). Westerners in China: A History of Exploration and Trade, Ancient Times Through the Present. McFarland. p. 74. ISBN 0-7864-1404-9.

- ^ Janin, Hunt (1999). The India–China Opium Trade in the Nineteenth Century. McFarland. p. 207. ISBN 0-7864-0715-8.

- ^ a b c Gray 2002, p. 22-23.

- ^ a b Spence 1999, p. 120.

- ^ a b Van Dyke, Paul A. (2005). The Canton trade: life and enterprise on the China coast, 1700-1845. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. pp. 6–9. ISBN 962-209-749-9.

- ^ Bernstein, William J. (2008). A splendid exchange: how trade shaped the world. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-87113-979-5.

- ^ Alain Peyrefitte, The Immobile Empire—The first great collision of East and West—the astonishing history of Britain's grand, ill-fated expedition to open China to Western Trade, 1792-94 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), p. 520

- ^ a b Peyrefitte 1993, p487-503

- ^ Early American Trade, BBC

- ^ Liu, Henry C. K. (4 September 2008). Developing China with sovereign credit. Asia Times Online.

- ^ Hanes III, W. Travis; Sanello, Frank (2002). The Opium Wars. Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks, Inc. p. 20.

- ^ Peyrefitte, 1993 p520

- ^ a b Peter Ward Fay, The Opium War, 1840-1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the Early Part of the Nineteenth Century and the Way by Which They Forced the Gates Ajar (Chapel Hill, North Carolina:: University of North Carolina Press, 1975).

- ^ a b c "China: The First Opium War". John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York. Retrieved 2 December 2010Quoting British Parliamentary Papers, 1840, XXXVI (223), p. 374

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ England and China: The Opium Wars, 1839–60

- ^ Commissioner Lin: Letter to Queen Victoria, 1839. Modern History Sourcebook.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2004, p. 41.

- ^ "Foreign Mud: The opium imbroglio at Canton in the 1830s and the Anglo-Chinese War," by Maurice Collis, W. W. Norton, New York, 1946

- ^ Poon, Leon. "Emergence Of Modern China". University of Maryland. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- ^ "Opiates". University of Missouri. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- ^ http://news.cultural-china.com/20090604103010.html

- ^ Coleman, Anthony (1999). Millennium. Transworld Publishers. pp. 243–244. ISBN 0-593-04478-9.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Jasper Ridley, Lord Palmerston, (1970) p. 248

- ^ Glenn Melancon, "Honor in Opium? The British Declaration of War on China, 1839-1840," International History Review (1999) 21#4 pp 854-874.

- ^ Glenn Melancon (2003). Britain's China Policy and the Opium Crisis: Balancing Drugs, Violence and National Honour, 1833-1840. Ashgate. p. 126.

- ^ H.G. Gelber, Harvard University Centre for European Studies Working Paper 136, 'China as Victim: The Opium War that wasn't'

- ^ Spence 1999, p. 153-155.

- ^ a b "No. 19930". The London Gazette. 15 December 1840.

- ^ Elliott, Jane E. (2002). Some Did it for Civilisation, Some Did it for Their Country: A Revised View of the Boxer War. Chinese University Press. ISBN 9789629960667. p. 197

- ^ Lin Zexu Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Opium War

- ^ East Asian Studies

- ^ Monument to the People's Heroes, Beijing - Lonely Planet Travel Guide

- ^ Lin Zexu Memorial

- ^ Lin Zexu Memorial Museum Ola Macau Travel Guide

- ^ Schell, Orville; John Delury (12 July 2013). "A Rising China Needs a New National Story". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- Bibliography

- Correspondence Relating to China (1840). London: Printed by T. R. Harrison.

- The Chinese Repository (1840). Volume 8.

- Fay, Peter Ward (1975). The Opium War, 1840-1842. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1243-9.

- Gray, Jack (2002). Rebellions and Revolutions: China from the 1800s to 2000. Short Oxford History of the Modern World. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870069-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hanes, W. Travis; Sanello, Frank (2004). Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks. ISBN 9-7814-0222-9695.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoe, Susanna; Roebuck, Derek (1999). The Taking of Hong Kong: Charles and Clara Elliot in China Waters. Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-1145-7.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1999). The Search for Modern China (second ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-97351-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Julia Lovell, The Opium War: Drug, Dreams and the Making of China (London, Picador, 2011 ISBN 0-330-45747-0). Well referenced narrative using both Chinese and western sources and scholarship.

- Hsin-Pao Chang. Commissioner Lin and the Opium War. (Cambridge,: Harvard University Press, Harvard East Asian Series, 1964).

- Peter Ward Fay, The Opium War, 1840-1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the early part of the nineteenth century and the way by which they forced the gates ajar (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1975).

- John King Fairbank, Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast; the Opening of the Treaty Ports, 1842-1854 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953).

- Michael Greenberg. British Trade and the Opening of China, 1800-42. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Studies in Economic History, 1951). Various reprints. Uses Jardine Matheson papers to detail the British side of the trade.

- Manhong Lin. China Upside Down: Currency, Society, and Ideologies, 1808-1856. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, Harvard East Asian Monographs, 2006). ISBN 0674022688. Detailed study of the economics of the trade.

- James M. Polachek, The Inner Opium War (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1992.) Based on court records and diaries, presents the debates among Chinese officials whether to legalize or suppress the use and trade in opium.

- Arthur Waley, The Opium War Through Chinese Eyes (London: Allen & Unwin, 1958; reprinted Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1968). Translations and narrative based on Lin's writings.

External links

- Peter C. Perdue, "The First Opium War: The Anglo-Chinese War of 1839-1842" (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2011. MIT Visualizing Cultures).

- "The Opium War and Foreign Encroachment," Education for Educators (Columbia University). Resources for teaching.

Fictional and narrative literature

- Leasor, James. Mandarin-Gold. London: Heinemann, 1973, e-published James Leasor Ltd, 2011

- Amitav Ghosh, River of Smoke (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2011).

- Timothy Mo, An Insular Possession (Chatto and Windus, 1986; Paddleless Press, 2002)