Amos Oz

Amos Oz עמוס עוז | |

|---|---|

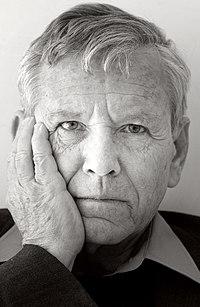

Oz in 2005 | |

| Born | Amos Klausner May 4, 1939 Jerusalem, Mandatory Palestine |

| Occupation | Writer, Novelist and Journalist |

| Nationality | Israeli |

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | Nily Oz-Zuckerman |

Amos Oz (Template:Lang-he-n; born May 4, 1939, birth name Amos Klausner) is an Israeli writer, novelist, journalist and intellectual. He is also a professor of literature at Ben-Gurion University in Beersheba. He is regarded as Israel's most famous living author.[1]

Oz's work has been published in 42 languages, including Arabic, in 43 countries. He has received many honours and awards, among them the Legion of Honour of France, the Goethe Prize, the Prince of Asturias Award in Literature, the Heinrich Heine Prize and the Israel Prize. In 2007, a selection from the Chinese translation of A Tale of Love and Darkness was the first work of modern Hebrew literature to appear in an official Chinese textbook.

Since 1967, Oz has been a prominent advocate of a two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Biography

Amos Klausner (later Oz) was born in Jerusalem in 1939, where he grew up at No. 18 Amos Street in the Kerem Avraham neighborhood.

His parents, Yehuda Arieh Klausner and Fania Mussman, were immigrants to Mandatory Palestine, who met while studying at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. His father's family was from Poland and Lithuania, where they had been farmers, raising cattle and vegetables near Vilna.[2] His father studied history and literature in Wilno, Poland and hoped to become a professor of comparative literature but never gained headway in the academic world. He worked most of his life as a librarian at the Jewish National and University Library.[3]

Oz's mother came from Rivne (now in the Ukraine, but then part of the Russian Empire). She was a highly sensitive and cultured daughter of a wealthy mill owner and attended Charles University in Prague where she studied history and philosophy. She had to abandon her studies when her father's business collapsed in the Great Depression.[4]

Oz's parents were multilingual (his father claimed he could read in 16 or 17 languages, while his mother spoke four or five different languages, but could read in 7 or 8) but neither was comfortable speaking in Hebrew. They spoke with each other in Russian and Polish[5] although the only language they allowed Oz to learn was Hebrew.

Many of Oz's family members were right-wing Revisionist Zionists. His great uncle Joseph Klausner was the Herut party candidate for the presidency against Chaim Weizmann and was chair of the Hebrew literature department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Oz and his family were not religious, considering it irrational. Oz, however, attended the community religious school Tachkemoni since the only alternative was a socialist school affiliated with the labour movement, to which his family was even more opposed. The noted poet Zelda was one of his teachers. After Tachkemoni he attended Gymnasia Rehavia.

His mother, who suffered from depression, committed suicide when he was 12. He would later explore the repercussions of this event in his memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness.

Two years after the suicide of his mother, at the age of 14, he became a Labor Zionist, left home, and joined kibbutz Hulda.[6]

There he was adopted by the Huldai family and changed his last name to "Oz", Hebrew for "strength." Asked why he did not leave Jerusalem for Tel Aviv, he later said, "Tel Aviv was not radical enough – only the kibbutz was radical enough." By his own account he was "a disaster as a laborer... the joke of the kibbutz." When Oz first began to write, the kibbutz allotted him one day per week for this work. When his book My Michael turned out to be a best-seller Oz quipped that he had become "a branch of the economy" and the kibbutz allotted him three days. By the 1980s he was given four days for writing, two for teaching, while continuing to take his turn as a waiter in the kibbutz dining hall on Saturdays.”[7]

Oz did his Israel Defense Forces service in the Nahal brigade, participating in border skirmishes with Syria. After concluding his army service he was sent by his kibbutz to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where he studied philosophy and Hebrew literature. He graduated in 1963 and began work as a teacher of literature and philosophy. He subsequently served with a tank unit in the Sinai Peninsula during the Six-Day War and in the Golan Heights during the Yom Kippur War.[7][8]

Oz married Nily Oz-Zuckerman in 1960. The couple has three children. The family continued to live at kibbutz Hulda until 1986, when they moved to Arad in the Negev for the sake of their son Daniel's asthma. Their oldest daughter, Fania Oz-Salzberger, teaches history at the University of Haifa.

Literary career

Oz's earliest publications were short articles in the kibbutz newsletter and the newspaper Davar. His first book Where the Jackals Howl, a collection of short stories, was published in 1965. His first novel Elsewhere, Perhaps was published in 1966. Subsequently Oz averaged a book per year with the Histadrut press Am Oved. Ultimately Oz left Am Oved for the Keter Publishing House, which offered him an exclusive contract that granted him a fixed monthly salary regardless of output.

Oz has published 38 books, among them 13 novels, four collections of stories and novellas, children’s books, and nine books of articles and essays (as well as six selections of essays that appeared in various languages), and about 450 articles and essays. His works have been translated into some 42 languages, including Arabic.[7]

Oz's political commentary and literary criticism have been published in the Histradrut newspaper Davar and Yedioth Ahronoth. Translations of his essays have appeared in the New York Review of Books. The Ben-Gurion University of the Negev maintains an archive of his work.

Oz tends to present protagonists in a realistic light with an ironic touch while his treatment of the life in the kibbutz is accompanied by a somewhat critical tone. Oz credits a 1959 translation of American writer Sherwood Anderson's short story collection Winesburg, Ohio with his decision to “write about what was around me.” In A Tale of Love and Darkness, his memoir of coming of age in the midst of Israel's violent birth pangs, Oz credits Anderson's “modest book” with his own realization that "the written world … always revolves around the hand that is writing, wherever it happens to be writing: where you are is the center of the universe." In his 2004 essay "How to Cure a Fanatic" (later the title essay of a 2006 collection), Oz argues that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not a war of religion or cultures or traditions, but rather a real estate dispute — one that will be resolved not by greater understanding, but by painful compromise.[9][10]

Political views

Oz was one of the first Israelis to advocate a two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict after the Six-Day War. He did so in a 1967 article "Land of our Forefathers" in the Labor newspaper Davar. "Even unavoidable occupation is a corrupting occupation," he wrote. In 1978, he was one of the founders of Peace Now. He does not oppose (and in 1991 advocated[8]) the construction of an Israeli West Bank barrier, but believes that it should be roughly along the Green Line, the pre-1967 border.[7] He has also advocated that Jerusalem be divided into numerous zones, not just Jewish and Palestinian zones; including, one for the Eastern Orthodox, one for Hasidic Jews, an international zone, and so on.[8]

He is opposed to Israeli settlement activity and was among the first to praise the Oslo Accords and talks with the PLO.[8] In his speeches and essays he frequently attacks the non-Zionist left and always emphasizes his Zionist identity. He is perceived as an eloquent spokesperson of the Zionist left.

For many years Oz was identified with the Israeli Labor Party and was close to its leader Shimon Peres. When Peres retired from party leadership, he is said to have named Oz as one of three possible successors, along with Ehud Barak (later Prime Minister) and Shlomo Ben-Ami (later Barak's foreign minister).[7] In the 1990s, Oz withdrew his support from Labor and went further left to the Meretz Party, where he had close connections with the leader, Shulamit Aloni. In the elections to the sixteenth Knesset that took place in 2003, Oz appeared in the Meretz television campaign, calling upon the public to vote for Meretz.

Oz was a supporter of the Second Lebanon War in 2006. In the Los Angeles Times, he wrote: "Many times in the past, the Israeli peace movement has criticized Israeli military operations. Not this time. This time, the battle is not over Israeli expansion and colonization. There is no Lebanese territory occupied by Israel. There are no territorial claims from either side… The Israeli peace movement should support Israel's attempt at self-defense, pure and simple, as long as this operation targets mostly Hezbollah and spares, as much as possible, the lives of Lebanese civilians. [11][12]

Oz changed his position of unequivocal support of the war as "self-defense" in the wake of the cabinet's decision to expand operations in Lebanon.[13]

A day before the outbreak of the 2008–2009 Israel–Gaza conflict, Oz signed a statement supporting military action against Hamas in the Gaza Strip. Two weeks later he advocated a ceasefire with Hamas and called attention to the harsh conditions there.[14] He was quoted in the Italian paper Corriere della Sera as saying Hamas was responsible for the outbreak of violence, but the time had come to seek a cease-fire.[15] Oz also said that if innocent citizens were indeed killed in Gaza, it should be treated as a war crime, although he doubted that bombing UN structures was intentional.[16]

In a New York Times editorial in June 2010, he wrote: “Hamas is not just a terrorist organization. Hamas is an idea, a desperate and fanatical idea that grew out of the desolation and frustration of many Palestinians. No idea has ever been defeated by force... To defeat an idea, you have to offer a better idea, a more attractive and acceptable one... Israel has to sign a peace agreement with President Mahmoud Abbas and his Fatah government in the West Bank.”[17]

In March 2011, Oz sent imprisoned former Tanzim leader Marwan Barghouti a copy of his book A Tale of Love and Darkness in Arabic translation with his personal dedication in Hebrew: “This story is our story, I hope you read it and understand us as we understand you, hoping to see you outside and in peace, yours, Amos Oz”.[18] The gesture was criticized by members of rightist political parties,[19] among them Likud MK Tzipi Hotovely.[20] Assaf Harofeh Hospital canceled Oz's invitation to give the keynote speech at an awards ceremony for outstanding physicians in the wake of this incident.[21]

Oz supported Israeli actions in Gaza during the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict, criticizing the alleged Hamas tactic of using human shields, saying: "What would you do if your neighbor across the street sits down on the balcony, puts his little boy on his lap, and starts shooting machine-gun fire into your nursery? What would you do if your neighbor across the street digs a tunnel from his nursery to your nursery in order to blow up your home or in order to kidnap your family?"[22][23]

Awards and recognition

- 1976 – Brenner Prize[24]

- 1983 – Bernstein Prize (original Hebrew novel category) for A Perfect Peace[25]

- 1984 – named a member of the Officier des Arts et Lettres in France.[26]

- 1986 – Bialik Prize for literature (jointly with Yitzhak Auerbuch-Orpaz)[27]

- 1988 – French Prix Femina Etranger[26][28]

- 1992 – Peace Prize of the German Book Trade[26][28]

- 1997 – named to the French Legion of Honour[26]

- 1998 – Israel Prize for literature[29]

- 2004 – Welt-Literaturpreis from the German newspaper Die Welt[30]

- 2004 – Ovid Prize from the city of Neptun, Romania[31]

- 2004 – "Premi Internacional Catalunya" of the Generalitat of Catalonia

- 2005 – Goethe Prize from the city of Frankfurt, Germany for his life's work[32]

- 2005 – JQ Wingate Prize (nonfiction) for A Tale of Love and Darkness

- 2006 – Jerusalem-Agnon Prize[26]

- 2006 – Corine Prize (Germany)[26]

- 2007 – Prince of Asturias Award in Literature (Spain)[26][33]

- 2007 – A Tale of Love and Darkness named one of the ten most important books since the creation of the State of Israel[26]

- 2008 – German President's High Honor Award[26]

- 2008 – Primo Levi Prize (Italy)[26]

- 2008 – Heinrich Heine Prize of Düsseldorf, Germany[26][34]

- 2008 – Honorary degree from the University of Antwerp

- 2008 – Tel Aviv University's Dan David Prize ("Past Category") (jointly with Atom Egoyan and Tom Stoppard), for "Creative Rendering of the Past"[35]

- 2008 – Foreign Policy/Prospect list of 100 top public intellectuals (#72)[36]

- 2010 – Honorary fellowship from the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

- 2013 – Franz Kafka Prize[37][38]

- 2014 – Order of Civil Merit[39]

- 2014 – Honorary decoration bestowed by the king of Spain.

- 2014 – The Siegfried Lenz literary prize, granted by the City of Hamburg.

- 2014 – The Jewish national award for book of the year for "Between Friends", USA.

- 2014 – Honorary doctorate, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland

- 2015 – The UCLA Israel studies program annual award.

- 2015 – A world premiere of the film "A Tale Of Love And Darkness", based on Amos Oz's novel, takes place in Cannes international film festival. The film is written, directed and starred by Natalie Portman.

- 2015 - Internationaler Literaturpreis – Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Germany, winner for Judas[40]

- 2015 - Honorary degree by the University of Milan (in Language and cultures for communication and international cooperation)[41]

Published works

Non-fiction

- In the Land of Israel (essays on political issues) ISBN 0-15-144644-X

- Israel, Palestine and Peace: Essays (1995) (Previously published: Whose Holy Land? (1994).)

- Under This Blazing Light (1995) ISBN 0-521-44367-9

- Israeli Literature: a Case of Reality Reflecting Fiction (1985) ISBN 0-935052-12-7

- The Slopes of Lebanon (1989) ISBN 0-15-183090-8

- The Story Begins: Essays on Literature (1999) ISBN 0-15-100297-5

- A Tale of Love and Darkness (2002) ISBN 0-15-100878-7

- How to Cure a Fanatic (2006) ISBN 978-0-691-12669-2

- Jews and Words (20 November 2012) Oz, Amos; Oz-Salzberger, Fania. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300156478

Fiction

- Where the Jackals Howl (1965) ISBN 0-15-196038-0

- Elsewhere, Perhaps (1966) ISBN 0-15-183746-5

- My Michael (1968) ISBN 0-394-47146-6

- Unto Death (1971) ISBN 0-15-193095-3

- Touch the Water, Touch the Wind (1973) ISBN 0-15-190873-7

- The Hill of Evil Counsel (1976) ISBN 0-7011-2248-X ; ISBN 0-15-140234-5

- Soumchi (1978) ISBN 0-06-024621-9 ; ISBN 0-15-600193-4

- A Perfect Peace (1982) ISBN 0-15-171696-X

- Black Box (1987) ISBN 0-15-112888-X

- To Know a Woman (1989) ISBN 0-7011-3572-7 ; ISBN 0-15-190499-5

- Fima (1991) ISBN 0-15-189851-0

- Don't Call It Night (1994) ISBN 0-15-100152-9

- Panther in the Basement (1995) ISBN 0-15-100287-8

- The Same Sea (1999) ISBN 0-15-100572-9

- The Silence of Heaven: Agnon's Fear of God (2000) ISBN 0-691-03692-6

- Suddenly in the Depth of the Forest (A Fable for all ages) (2005)

- Rhyming Life and Death (2007) ISBN 978-0-7011-8228-1

- Scenes from Village Life (2009)

- Between Friends (2012)

- Judas (2014)

Short stories

- Oz, Amos (January 22, 2007). "Heirs". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- Oz, Amos (December 8, 2008). "Waiting". The New Yorker. 84 (40): 82–89. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- Oz, Amos (January 17, 2011). "The King of Norway". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

See also

References

- ^ [1] By Robert Tait, Jerusalem, Daily Telegraph

- ^ A Tale of Love and Darkness, By Amos Oz, Random House, 2005, page 81

- ^ Voices of Israel: Essays on and Interviews with Yehuda Amichai, A. B. Yehoshua, T. Carmi, Aharon Appelfeld, and Amos Oz, Joseph Cohen

- ^ A Tale of Love and Darkness, Amos Oz, Random House, 2005, page 180

- ^ A Tale of Love and Darkness, Amos Oz, Random House, 2005, page 2

- ^ Amos Oz makes room for his loneliness, Haaretz

- ^ a b c d e Remnick, David, "The Spirit Level". The New Yorker, November 8, 2004

- ^ a b c d Amos Oz interview with Phillip Adams, 10 September 1991, re-broadcast on ABC Radio National 23 December 2011

- ^ Review of A Tale of Love and Darkness from National Review[dead link]

- ^ “Return from Oz”. Review of The Slopes of the Volcano from Azure magazine, Autumn 2006, no. 26

- ^ Caught in the crossfire; Hezbollah attacks unite Israelis Jul 19, 2006

- ^ Hezbollah Attacks Unite Israelis July 19, 2006

- ^ Author David Grossman's son killed – Israel News, Ynetnews

- ^ Oz, Amos (02.13.08). "Don't march into Gaza". Yediot Aharonot. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Amos Oz: Hamas responsible for outbreak of Gaza violence". haaretz.com. December 30, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2009.

- ^ Edemariam, Aida (February 14, 2009). "A life in writing: Amos Oz". The Guardian. London. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Oz, Amos (June 1, 2010). "Israeli Force, Adrift on the Sea". New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Amos Oz calls for Barghouti's release in book dedication". Jerusalem Post. March 15, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ Brut, Zvika (March 16, 2011). "Amos Oz sends book to jailed Barghouti". Ynet, Israel News. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ Book of Esther: Jewish fate ever since, Tzipi Hotovely, Israel Today" 17/03/2011

- ^ Levy, Gideon (March 27, 2011). "Who is sick enough to censor Amos Oz?". Haaretz. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ Gourevitch, Philip (August 2, 2014). "An Honest Voice in Israel". The New Yorker.

- ^ Goldberg, Jeffrey (August 1, 2014). "The Most Dangerous Moment in Gaza". The Atlantic.

- ^ Amos Oz – University of Gen-Gurion Website (In Hebrew)

- ^ Amos Oz (Prizes, Awards, and Honors)- University of Gen-Gurion Website (English)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Biography and Bibliography at the Institute for Translation of Hebrew Literature[dead link]

- ^ "List of Bialik Prize recipients 1933–2004 (in Hebrew), Tel Aviv Municipality website" (PDF).

- ^ a b Biography at Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ "Israel Prize Official Site – Recipients in 1998 (in Hebrew)".

- ^ "WELT-Literaturpreis an Amos Oz verliehen". Berliner Morgenpost (in German). November 13, 2004. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ "Amos Oz receives Romanian Ovidius Prize".

- ^ Lev-Ari, Shiri (September 15, 2005). "Two kids head off in search of truth". Haaretz. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ Akiva Eldar, "Border Control / The Spanish conquest", Haaretz, 30/10/2007

- ^ "Literatur-Auszeichnung: Amos Oz gewinnt Heine-Preis" (in German). Spiegel Online. June 21, 2008.

- ^ "Dan David Prize Official Site – Laureates 2008". Dan David Prize.

- ^ List: the 100 leading intellectuals. World's top thinkers according to a survey by Prospect and Foreign Policy magazines, The Guardian, June 23, 2008

- ^ "Israeli Author Amos Oz Wins Franz Kafka Prize". AP. May 27, 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ^ "Amos Oz – the New Laureate of the Franz Kafka Prize". Franz Kafka Society. 28 May 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ^ "Amos Oz – Gran Cruz de la Orden del Merito". EFE. Jan 4, 2014. Retrieved Jan 4, 2014.

- ^ Sabine Peschel (June 29, 2015). "Amos Oz wins major German literature award". DeutscheWelle. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "Laurea honoris causa ad Amos Oz" (in Italian). 2015-07-16.

External links

- Template:En icon / Template:He icon Amos Oz Archive

- Amos Oz is most translated Israeli author

- 2008 Dan David Prize laureate

- Amos Oz – The Nature of Dreams, Documentary film about Amos Oz: In-depth interviews, situations and literature quotes

- Heinrich Heine Award for Amos Oz: A Literary Bridge-Builder Par Excellence

- Tal Niv from Haaretz speaks with Amos Oz about "Rhyming Life and Death" and more

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Amos Oz interviewed on CBC Radio's Writers and Company (2010)

- "The Art of Fiction, No. 148" (Amos Oz interview), The Paris Review (Fall 1996)

Articles

- “Arafat's gift to us: Sharon”, The Guardian, February 8, 2001

- “An end to Israeli occupation will mean a just war”, The Observer, April 7, 2002

- “Free at last”, Ynetnews, August 21, 2005

- “This can be a vote for peace”, The Guardian, March 30, 2006

- “Defeating the extremists”, Ynetnews, November 21, 2007

- “Don't march into Gaza”, Ynetnews, February 13, 2008

- “Secure ceasefire now”, Ynetnews, December 31, 2008

- http://www.tcd.ie/registrar/honorary-degrees/

- 1939 births

- Ben-Gurion University of the Negev faculty

- Hebrew University of Jerusalem alumni

- Israel Prize in literature recipients

- Bernstein Prize recipients

- Bialik Prize recipients

- Brenner Prize recipients

- Israeli atheists

- Israeli Jews

- Israeli people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent

- Israeli people of Polish-Jewish descent

- Israeli people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent

- Israeli journalists

- Israeli essayists

- Israeli memoirists

- Israeli novelists

- Israeli translators

- Israeli non-fiction writers

- Jewish novelists

- Jewish atheists

- Living people

- Members of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts

- People from Jerusalem

- Kibbutzniks

- Prix Femina Étranger winners

- Chevaliers of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- Israeli men