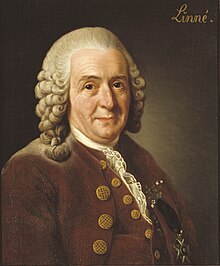

Carl Linnaeus

Carolus Linnaeus, also known after his ennoblement as , (May 23, 1707 – January 10, 1778), was a Swedish botanist, physician and zoologist[1] who laid the foundations for the modern scheme of nomenclature. He is also considered one of the fathers of modern ecology (see History of ecology). He is known as the "father of modern taxonomy."

Name

The name of this botanist comes in different variants: 'Carl Linnaeus', 'Carolus Linnaeus' and 'Carl von Linné', sometimes just 'Carl Linné'. There is often confusion about his real Swedish name, as opposed to the Latinized form 'Carolus Linnaeus' he used most when he published his scientific works in Latin.

In Linnaeus' time, most Swedes had no surnames. Linnaeus' grandfather was named Ingemar Bengtsson (son of Bengt), according to Scandinavian tradition. Linnaeus' father was known as Nils Ingemarsson (son of Ingemar). Only for registration purposes, for example when matriculating at a university, one needed a surname. In the academic world, Latin was the language of choice, so when Linnaeus' father went to the University of Lund, he coined himself a Latin surname: Linnaeus, referring to a large linden (lime) tree[2] on the family property Linnagård (linn being an archaic form of Swedish lind, the linden). Nils Ingemarsson Linnaeus gave his son the name Carl. So the Swedish name of the boy was Carl Linnaeus[3].

When Carl Linnaeus enrolled as student at the University of Lund, he was registered as 'Carolus Linnaeus'. This Latinized form was the name he used when he published his works in Latin. After he was ennobled, in 1761[4], he took the name Carl von Linné. 'Linné' is thus a shortened version of 'Linnaeus', 'von' is added to signify his ennoblement.

When referring to or citing the author Linnaeus, it is appropriate to use 'Carl Linnaeus', 'Carolus Linnaeus' or just 'Linnaeus'. 'Carl von Linné' seems to be less suitable, especially for the works he published before 1762. On the title page of the second edition of Species plantarum (1762) the author's name is still printed as 'Carolus Linnaeus' (or rather the genitive form 'Caroli Linnaei') but from then on, his name is quite consistently printed as 'Carolus a Linne' or 'Carl von Linné'. Stafleu[1] uses 'Carl Linnaeus' as the author's name for all his works.

The adjective of his name is usually 'Linnaean', but the prestigious Linnean Society of London has a journal The Linnean, awards the Linnean Medal, and so on.

Biography

Early life

Carl Linnaeus was born on a farm in May 23, 1707. The farm was called Råshult, located in Älmhult Municipality, in the province of Småland in southern Sweden. Linnaeus was groomed as a youth to be a churchman, walking in his fathers path, but showed little enthusiasm for it. In 1717 he was sent to school the primary school at the city Växjö, and in 1724 he passed to the gymnasium there, but with meager results in the clerical faculty. Instead his interest in botany made an impression on a local physician, realizing there might be a bright future in the field for Carl, and on his recommendation Carl's father sent Carl to study at the closest university, Lund University. Carl studied in Lund and tried to make something of the botanical garden there, but because it had been neglected, it was suggested to him that he would have better prospects at the University of Uppsala; Carl left for Uppsala within a year.

His first time in Uppsala were financially rough, until he was acquainted with the renowned scientist Olof Celsius in 1729. Celsius, impressed with Linnaeus's knowledge and botanical collections, offered him board and lodging.

During this period, he came upon a work which ultimately led to the establishment of his artificial system of plant classification. This was a review of Sebastien Vaillant's Sermo de Structura Florum (Leiden, 1718), a thin quarto in French and Latin. Through this, he became convinced of the importance of the stamens and pistils, on which he in 1729 wrote a short treatise on the sexes of plants. It caught the attention of Olof Rudbeck the Younger (1660-1740), the professor of botany in the university, who subsequently appointed him his adjunct. In 1730, Carl began giving lectures in the faculty.

In 1732 the Academy of Sciences at Uppsala financed Linnaeus on an expedition to Lapland in northernmost Sweden, then virtually unknown. The result of this was first The Florula Lapponica (the first work to use the Sexual System) and later the Flora Lapponica published in 1737. His journey to sub-Arctic Lapland is notable for exotic and adventurous episodes.

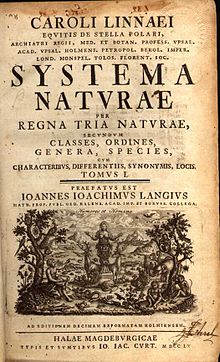

Systema Naturae

In 1735 Linnaeus moved to the continent. In the Netherlands he earned his one and only academic degree. He also met Jan Frederik Gronovius and showed him a draft of his work on taxonomy, the Systema Naturae. This was published in the Netherlands the same year, as an eleven page work.

By the time it reached its 10th edition (1758), it classified 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants. In it, the unwieldy names mostly used at the time, such as "Physalis annua ramosissima, ramis angulosis glabris, foliis dentato-serratis", were supplemented with concise and now familiar "binomials", composed of the generic name, followed by a specific epithet, e.g. Physalis angulata. These binomials could serve as a label to refer to the species. Higher taxa were constructed and arranged in a simple and orderly manner. Although the system, now known as binomial nomenclature, was developed by the Bauhin brothers (see Gaspard Bauhin and Johann Bauhin) almost 200 years earlier, Linnaeus was the first to use it consistently throughout the work, also in monospecific genera, and may be said to have popularized it within the scientific community.

Linnaeus named taxa in ways that personally struck him as common-sensical; for example, human beings are Homo sapiens (see sapience). He also briefly described a second human species, Homo troglodytes ("cave-dwelling man"). This was however likely a confusion originating from exaggerated second- or third-hand accounts of the chimpanzee (currently most often placed in a different genus, as Pan troglodytes). The group "mammalia" are named for their mammary glands because one of the defining characteristics of mammals is that they nurse their young.

Travels and research

Linnaues stayed in the Netherlands for 12 months. In 1736, he made a trip to London, where he visisted the Oxford University and met several highly regarded people, such as the phycisist Hans Sloane, the botanic Philip Miller and the professor of botany J. J. Dillenius. After returning to Amsterdam, he continued the work of arranging Clifford's collection of plants. In 1738, he left back home, but stayed in Leiden for a year, during which he had his Classes Plantarum printed; then travelling to Paris, before setting sail for Sweden.

Arriving in Stockholm, he settled as a physicist in September that year. In 1739 Linnaeus married Sara Morea in Stockholm, and in the same year he was one of the founders of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In 1741 he ascended to the chair of medicine at Uppsala and moved there. The position was soon exchanged for the chair of botany.

Throughout the 1740s he conducted numerous field trips to many locations in Sweden to classify plants and animals. In 1741 to the islands of Öland and Gotland; in 1746 to Västergötland; and in 1749 to Skåne. The reports of each travel were published in the Swedish language to be assessable for the general public. They are noted for the fine treatment of the language, as well as containing an abundancy of interesting facts and events of that time.

When not on travels, Linnaeus worked on his classifications, extending them to the kingdom of animals and the kingdom of minerals. The last may seem somewhat odd, but the theory of evolution was still a long time away. Linnaeus was only attempting a convenient way of categorizing the elements of the natural world. Still, Linnaeus' research had begun to take science on a path that diverged from what had been taught by religious authorities; the local Lutheran Archbishop had accused him of "impiety." In a letter [1] to Johann Georg Gmelin dated February 25, 1747, Linnaeus wrote:

Non placet, quod Hominem inter ant[h]ropomorpha collocaverim, sed homo noscit se ipsum. Removeamus vocabula. Mihi perinde erit, quo nomine utamur. Sed quaero a Te et Toto orbe differentiam genericam inter hominem et Simiam, quae ex principiis Historiae naturalis. Ego certissime nullam novi. Utinam aliquis mihi unicam diceret! Si vocassem hominem simiam vel vice versa omnes in me conjecissem theologos. Debuissem forte ex lege artis. |

It is not pleasing that I placed humans among the primates, but man knows himself. Let us get the words out of the way. It will be equal to me by whatever name they are treated. But I ask you and the whole world a generic difference between men and simians in accordance with the principles of Natural History. I certainly know none. If only someone would tell me one! If I called man an ape or vice versa I would bring together all the theologians against me. Perhaps I ought to scientifically, |

The Swedish king, Adolf Fredrik, ennobled Linnaeus in 1757, and after the privy council had confirmed the ennoblement Linnaeus took the surname von Linné, later often signing just Carl Linné.

Last years

A stroke in 1774 greatly weakened him, and two years later he suffered another, losing the use of his right side. He died on January 1778 in Uppsala, during a cermon in the Uppsala Cathedral. He was buried in the cathedral.

Linnaean taxonomy

Taxonomists, in almost any biological field, have heard of Carolus Linnaeus. His prime contribution was to establish conventions for the naming of living organisms that became universally accepted in the scientific world (binomial names, scientific names): the work of Linnaeus represents the starting point of binomial nomenclature. In addition Linnaeus developed, during the great 18th century expansion of natural history knowledge, what became known as the Linnaean taxonomy; the system of scientific classification now widely used in the biological sciences.

The Linnaean system classified nature within a hierarchy, starting with three kingdoms. Kingdoms were divided into Classes and they, in turn, into Orders, which were divided into Genera (singular: genus), which were divided into Species (singular: species). Below the rank of species he sometimes recognised taxa of a lower (unnamed) rank (for plants these are now called "varieties").

Though the Linnaean system has proven robust, expansion of knowledge has led to an expansion of the number of hierarchical levels within the system, increasing the administrative requirements of the system (see, for example, ICZN), though it remains the only extant working classification system at present that enjoys universal scientific acceptance. Among the later subdivisions that have arisen are such entities as Phyla (singular: phylum), Superclasses, Superorders, Infarorders, Families, Superfamilies and Tribes. Many of these extra hierarchical levels tend to arise in disciplines such as entomology, whose subject matter is replete with species requiring classification. Any biological field that is species rich, or which is subject to a revision of the state of extant knowledge concerning those species and their relationships to each other, will inevitably make use of the additional hierarchical levels, particularly if integration of living organisms with fossils is performed, and the application of newer classification tools such as cladistics to facilitate this takes place.

Groups of organisms at any rank are now called taxa (singular: taxon) or taxonomic groups.

The task of identifying and describing all living species is called the Linnaean enterprise by modern ecologists.

His groupings were based upon shared physical characteristics. Although only his groupings for animals remain to this day, and the groupings themselves have been significantly changed since Linnaeus' conception, as well as the principles behind them, he is credited with establishing the idea of a hierarchical structure of classification which is based upon observable characteristics. While the underlying details concerning what are considered to be scientifically valid 'observable characteristics' has changed with expanding knowledge (for example, DNA sequencing, unavailable in Linnaeus' time, has proven to be a tool of considerable utility for classifying living organisms and establishing their relationships to each other), the fundamental principle remains sound.

Linnaeus was also a pioneer in defining the now discredited concept of "race" as applied to humans. Within Homo sapiens he proposed four taxa of a lower (unnamed) rank. These categories are, Americanus, Asiaticus, Africanus, and Europeanus. They were based on place of origin at first, and later skin color. Each race had certain characteristics that were endemic to individuals belonging to it. Native Americans were reddish, stubborn, and angered easily. Africans were black, relaxed and negligent. Asians were sallow, avaricious, and easily distracted. Europeans were white, gentle, and inventive. Linnaeus's races were clearly skewed in favour of Europeans. Over time, this classification led to a racial hierarchy, in which Europeans were at the top. Unfortunately, this classification scheme was used by members of many European countries to validate their conquering or subjugation of members of the "lower" races. In particular the invented concept of race was used to enforce the inhumane institution of slavery, particularly in the new world European colonies.

In addition, in Amoenitates academicae (1763), he defined Homo anthropomorpha as a catch-all race for a variety of human-like mythological creatures, including the troglodyte, satyr, hydra, and phoenix. He claimed that not only did these creatures actually exist, but were in reality inaccurate descriptions of real-world ape-like creatures.

He also, in Systema Naturæ, defined Homo ferus as "four-footed, mute, hairy." It included the subraces Juvenis lupinus hessensis (wolf-boys), whom he thought were raised by animals, and Juvenis hannoveranus (Peter of Hanover) and Puella campanica (Wild-girl of Champaigne). He likewise defined Homo monstrosous as agile and fainthearted, and included in this race the Patagonian giant, the dwarf of the Alps, and the monorchid Hottentot.

Template:Carolus Linnaeus Racial Definitions

Students

Carolus imbued his students with his own thouroughness in an atmosphere of enthusiasm, trained them to close and accurate observation, and then sent them to various parts of the globe. Some of the notable students include Pehr Kalm, in North America 1748–1751; Daniel Solander, with James Cook's to the Pacific in 1768, and in 1771 travelled to Iceland, the Faroes and the Orkney Islands; Fredric Hasselquist, who visited Palestine and parts of Asia Minor; and Carl Peter Thunberg to Japan, South Africa, Java, and Sri Lanka.

See also Wikipedia's category: students of Linnaeus.

Other accomplishments

- Linnaeus' original botanical garden may still be seen in Uppsala.

- He originated the practice of using the ♂ - (shield and arrow) Mars and ♀ - (hand mirror) Venus glyphs as the symbol for male and female.

- His picture can be found on the current Swedish 100 kronor bank notes [2].

- Linnaeus was one of the founders of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

- Linnaeus is the only botanist currently referred to by a single initial: L. (Previously, the abbreviation assigned was Linn.) In botany, the scientific authority for a botanical name is listed immediately after the name. For example, Cocos nucifera L. is the complete scientific name for the coconut, with the "L." referring to Carolus Linnaeus.

- Linnaeus was said to be a man of great social skills. Erik Axel Karlfeldt's words "han talte med bönder på bönders vis, och med lärde män på latin" [he talked to peasants as peasants do, and to learned men in Latin] give a good characterization of his manner.

- He was one of the pioneers in the field of chronobiology, and created the "Petal Time Clock". His findings found that different species of flowers open at different times everyday. For example, he discovered that the hawksbeard plant, opened its flowers at 6:30 am, whereas another species, the hawkbit, did not open its flowers until 7 am. After much research into this, he soon concluded that one could tell the time of day simply by watching the flowers in their garden.

See also

- Carolus Linnaeus the Younger. Linnaeus's son, also named Carl Linnaeus and also a botanist, is commonly so referred with filius (abbreviated "L. f.") to distinguish him from his famous father.

- Linnean Society of London

- Linnaeus Arboretum

- Jonas C. Dryander

- Peter Artedi

- Sir John Hill (1716-1775). One of Linnaeus' most constant correspondents in England.

Notes and references

- ^ a b Stafleu, F.A. (1976-1998) Taxonomic Literature second edition. An authoritative work on the names of botanists, their works and publication data, issued under the auspices of the IAPT.

- ^ Template:Sv icon Lind on Den virtuella floran, by The Swedish Museum of Natural History, accessed on 14 May 2006

- ^ Stearn, W.T. (1992), Botanical Latin, fourth edition: p. 283-284, Timber Press, Portland, Oregon. ISBN 0-88192-321-4.

- ^ W.T. Stearn, (1957), An introduction to the Species Plantarum and cognate botanical works of Carl Linnaeus, Principal events in the life of Linnaeus; in: Carl Linnaeus, Species Plantarum, A Facsimile of the first edition 1753, Volume I: 14, Ray Society, London.

External links

- Carl von Linne Carl von Linne (1707 - 1778)

- Linnaeus Botanical Garden

- Biography at the Department of Systematic Botany, University of Uppsala

- Biography at The Linnean Society of London

- Biography at the University of California Museum of Paleontology

- Exhibition: "Order from Chaos: Linnaeus Disposes"

- The Linnaean Correspondence

- Carl Linnaeus - The World's First Round Cultured Pearls