Woman Suffrage Procession

The woman suffrage parade of 1913, officially the Woman Suffrage Procession, was the first suffragist parade in Washington, D.C. Organized by the suffragist Alice Paul for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Thousands of suffragists marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., on Monday, March 3, 1913. The event was scheduled on the day before President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration to "march in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women are excluded," as the official program stated. The march and the attention that it attracted were monumental in advancing women's suffrage in the United States.[1]

In 2016, Secretary Lew announced plans for the new $10 to feature an image of the historic march for suffrage that ended on the steps of the Treasury Department and honor many of the leaders of the suffrage movement including Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul. The front of the new $10 note will maintain the portrait of Alexander Hamilton. The parade is scheduled to be depicted and honored on the redesign of the United States ten-dollar bill in 2020. No further action has yet been taken toward the adoption of the new design.[2]

Background

American suffragists Alice Paul and Lucy Burns spearheaded a drive to adopt a national strategy for women's suffrage in the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Both women had been influenced by the militant tactics used by the British suffrage movement and recognized that the women from the six states that had full suffrage at the time comprised a powerful voting bloc. They submitted a proposal to Anna Howard Shaw and the NAWSA leadership at their annual convention in 1912. The leadership was not interested in changing the state-by-state strategy and rejected the idea of holding a campaign that would hold the Democratic Party responsible. Paul and Burns appealed to prominent reformer Jane Addams, who interceded on their behalf.[3]

The women persuaded NAWSA to endorse an immense suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., to coincide with newly-elected President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration the following March. Paul and Burns were appointed chair and vice-chair of NAWSA's Congressional Committee.[4] They recruited Crystal Eastman, Mary Ritter Beard, and Dora Lewis to the Committee and organized volunteers, planned for, and raised funds in preparation of the parade with little help from the NAWSA.[5] Affiliates of NAWSA from various states organized groups to march and activities leading up to the march, such as the Suffrage Hikes.[6]

Plans for the march were threatened when black suffragists announced they intended to participate, which lead white southern suffragists to threaten to boycott the event.[7] One solution discussed was segregating the black suffragists in a separate section to mollify white southern delegates.[8]

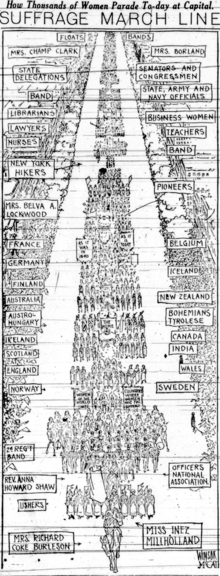

The parade itself was led by labor lawyer Inez Milholland, dressed dramatically in white and mounted on a white horse,[9] and included nine bands,[10] five mounted brigades, 26 floats, and close to 8,000 marchers,[11] including many notables such as Helen Keller, who was scheduled to speak at Constitution Hall after the march. Individuals came from European nations, Canada, India, Australia, New Zealand and many other countries around the world to support the movement. Most of the women marched in groups determined by their occupation or under their respective banners. Jeannette Rankin, from Montana, marched under her state's sign; she returned to Washington four years later as a U.S. Representative.[12]

-

A horse-drawn parade entry, from the side

-

The same entry from the rear

-

The Women Band

After a good beginning, the marchers encountered crowds, mostly male, on the street that should have been cleared for the parade. They were jeered and harassed while attempting to squeeze by the scoffing crowds, and the police, said to be of little help, sometimes even participated in the harassment. The Massachusetts and the Pennsylvania national guards stepped in. Eventually, boys from the Maryland Agricultural College created a human barrier protecting the women from the angry crowd and helping them progress forward to their destination.[13] Over 200 people were treated for injuries at local hospitals.[14] Still, most of the marchers finished the parade and viewed an allegorical tableau presented near the Treasury Building.[1] The pageant was written by dramatist Hazel MacKaye and directed by Glenna Smith Tinnin.[12]

Anti-black racism

Considerable debate exists about the segregation of black woman suffragists in the parade. A contemporaneous newspaper account indicated that Alice Paul objected to participation of "Negro" suffragists, but Anna Howard Shaw insisted that they to be allowed to participate.[15] In a 1974 oral history interview, Alice Paul recalled the "hurdle" of Mary Church Terrell planning to bring a delegation from the National Association of Colored Women.[16]

Delegations from the National Association of Colored Women and from the new Alpha Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta sorority from Howard University participated and black women marched in various state and occupational groups. While in Paul's memory, a compromise was reached to order the parade as southern women, then the men's section, and finally the Negro women's section, reports in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People paper, The Crisis, depict events unfolding quite differently, with black women protesting the plan to segregate them.[17] What is clear is that some groups attempted, on the day of the parade, to segregate their delegations, but women like Ida B. Wells-Barnett refused to comply.[18]

Aftermath

The mistreatment of the marchers by the crowd and the police caused a great uproar. Alice Paul shaped the public response after the parade, portraying the incident as symbolic of systemic government mistreatment of women, stemming from their lack of a voice and political influence through the vote. She claimed the incident showed that the government's role in women's lives had broken down, and that it was incapable of even providing women with physical safety.

Journalist Nellie Bly, who had participated in the march, headlined her article "Suffragists are Men's Superiors". Senate hearings, held by a subcommittee of the Committee on the District of Columbia, started on March 6, only three days after the march, and lasted until March 17, with the result that the District's superintendent of police was replaced.[19] NAWSA praised the parade and Paul's work on it, saying "the whole movement in the country has been wonderfully furthered by the series of important events which have taken place in Washington, beginning with the great parade the day before the inauguration of the president".[1]

Popular culture

The Woman Suffrage Procession plays a significant role in the 2004 film Iron Jawed Angels, which chronicles the strategies of Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and the National Woman's Party as they lobby and demonstrate for the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would assure voting rights for all American women.[20]

2020 United States ten-dollar bill

The U.S. Treasury Department announced in 2016 that an image of the Woman Suffrage Procession will appear on the back of a newly designed $10 bill along with images of Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Alice Paul. Designs for new $5, $10 and $20 bills will be unveiled in 2020 in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of American women winning the right to vote via the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[21]

See also

- Silent Sentinels

- Suffrage Hikes

- 1907 Mud March (UK)

- Women's Sunday (1908, UK)

- Women's Coronation Procession (1911, UK)

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- Timeline of women's suffrage

Notes

- ^ a b c Harvey, Sheridan. "Marching for the Vote: Remembering the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913". American Women: A Library of Congress Guide for the Study of Women's History and Culture in the United States. Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ ""Treasury Secretary Lew Announces Front of New $20 to Feature Harriet Tubman, Lays Out Plans for New $20, $10 and $5", United States Treasury website".

- ^ Lunardini 1986, pp. 20–21

- ^ Lunardini 1986, pp. 21–22

- ^ Lunardini 1986, pp. 23–24

- ^ Baer, Ellen D. (2002). Enduring Issues in American Nursing. New York: Springer Pub. Co. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-8261-1632-1.

- ^ Crystal Nicole Feimster (2009). Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching. Harvard University Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-674-03562-1.

- ^ J.D. Zahniser; Amelia R. Fry. Alice Paul: Claiming Power. pp. 137–141. ISBN 978-019-995842-9.

- ^ Adams, Katherine (2008). Alice Paul and the American Woman Suffrage Campaign. Chicago: University of Illinois. p. 104.

- ^ "Marching for the Vote: Remember the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913". American Women. Library of Congress. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ Estimates for the number of marchers varied, with the Congressional Committee claiming 10,000. Most accounts quoted the 8000 figure; see The New York Times, March 3, 1913, and Lunardini 1986, p. 28

- ^ a b Woelfle, Gretchen (2009). "TAKING IT to the STREET." Cobblestone. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Flexner, Eleanor (1956). Century of Struggle. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^ The Washington Post, March 5, 1913; The New York Times, March 4–5, 1913

- ^ "Colored Women in Suffrage Parade". Richmond, Virginia): The Times-Dispatch. March 2, 1913. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 29, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gallagher, Robert A. (1974). "I Was Arrested, Of Course". American Heritage. 25 (2): 20.

- ^ "Marching for the Vote: Remember the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913". American Women. Library of Congress. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ Jill Diane Zahniser; Amelia R. Fry (2014). Alice Paul: Claiming Power. Oxford University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-19-995842-9.

- ^ Suffrage Parade: Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the District of Columbia, Government Printing Office, 1913

- ^ "African American Women and Suffrage". National Women's History Museum. Retrieved 2015-07-30.

- ^ "Treasury Secretary Lew Announces Front of New $20 to Feature Harriet Tubman, Lays Out Plans for New $20, $10 and $5". Dept. of the Treasury. April 20, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

References

- Brown, Harriet Connor, ed., "Official Program, Woman Suffrage Procession, Washington, D. C., March 3, 1913" (Washington, 1913), Library of Congress. [1]

- Harvey, Sheridan. "American Women: Marching for the vote: Remembering the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913." American Women: A Library of Congress Guide for the Study of Women's History and Culture in the United States. January 1, 2001. Accessed April 6, 2015.

- Lunardini, Christine A. (1986). From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910–1928. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5022-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - unknown. "Views of Washington, D.C. suffrage parade and crowds. See individual photos for additional description." (1913): ARTstor Digital Library, EBSCOhost (accessed March 26, 2015).

- Woelfle, Gretchen. "TAKING IT to the STREET." Cobblestone 30, no. 3 (March 2009): 30. MasterFILE Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed March 22, 2015).

External links

- "The New $10 Note", United States Treasury website, includes more images of the procession.

Media related to Woman Suffrage Procession at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Woman Suffrage Procession at Wikimedia Commons